27 Orthopaedic surgery

Introduction

Examination

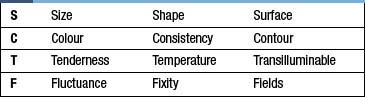

Feel

Palpate around the joint or limb. Establish areas of pain, and try to relate these to anatomical structures (e.g. tendons, joint lines etc.). Establish the presence of any swelling and whether this is fluctuant or solid (Table 27.1). Test the neurovascular status of the limb (sensation to light touch and pinprick, and peripheral pulses) and compare with this to the other side.

Investigations

Computed tomography (CT)

CT provides excellent images of bone anatomy (Fig. 27.1) and can be used to supply three-dimensional images to help in the reconstruction of complex fractures. The thin axial slices are particularly useful as a guide for obtaining biopsy specimens

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI (Fig. 27.2) provides excellent images of soft tissue, joint and bone pathology without exposure to radiation. It is widely used in virtually all branches of orthopaedics for diagnosis and preoperative planning.

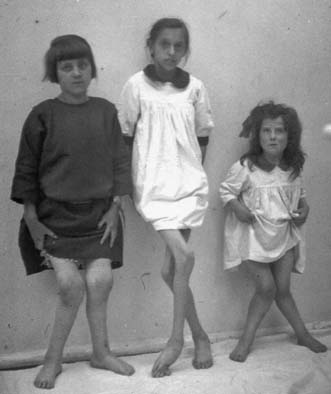

Description of deformity

With patients in the anatomical position (i.e. lying on their back with their palms pointing up to the ceiling), limb deformities are described relative to the midline (away = valgus, towards = varus) and to the alignment of the limb below the joint or deformity. For example, with respect to the knees, bowleggedness is a varus deformity, while knock-knees are a valgus deformity (Fig. 27.4). With the patient viewed from the side, there is a range of descriptive terms available. For example, hyperextension of the knee joint is known as recurvatum (Fig. 27.5). The three types of spinal deformity are:

• kyphosis: forward flexion (‘the kyphotic kisses his knees’).

• lordosis: the opposite, extension, or bent-over-backwards deformity; this represents the normal alignment of the lumbar and cervical spine.

• scoliosis: a sideward deformity that is normally associated with a degree of rotation (Fig. 27.6).

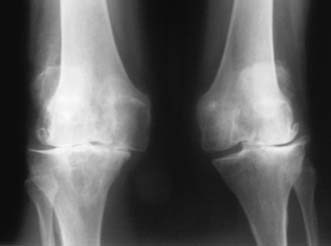

Osteoarthritis: degenerative disease of the joints

Osteoarthritis (OA) of a joint may occur as a primary idiopathic condition or secondary to problems such as malalignment, intra-articular fractures or over-stressing (obesity, overuse). In some patients, there is a strong genetic component. OA may occur in any joint (shoulder, elbow, wrist and hands) but predominantly affects those that are weight-bearing (hip and knee) (Figs 27.7 and 27.8). Idiopathic OA is generally of slow onset and affects the elderly. Secondary OA can affect the young and may develop quite rapidly when a joint injury leads to loss of articular cartilage. On plain X-ray, OA is associated with:

• joint space loss due to thinning of articular cartilage

• sclerosis of the joint surface, with the development of increased density of the bone just under the joint space

The treatment of OA may be conservative or operative (Table 27.2). The former focuses on the use of drugs and physical methods of pain and stress relief to the joint.

| Non-operative | Operative |

|---|---|

| Analgesia Physiotherapy Orthotics Injections Lifestyle modifications |

Osteotomy Joint debridement Excisional osteotomy Joint replacement (arthroplasty) Joint fusion (arthroplasty) |

Surgical management of OA

Osteotomy

This is useful in the younger patient, in whom joint replacement may not be advisable. The aim is to change the axis of the joint, so that a portion of the joint surface that has thus far been protected from wear and tear now forms the weight-bearing area. For example, with respect to the knee, although there may be severe OA of the medial compartment in conjunction with a varus deformity, the lateral compartment may have well-preserved articular cartilage. Over-correcting the varus deformity by means of osteotomy (removing wedges of bone from the tibia), so that body weight is now largely transmitted through the lateral compartment, may lead to significant improvement in symptoms, thus delaying the need for joint replacement (Fig. 27.9). Osteotomies generally use opening wedges (adding bone), closing wedges (removing bone) or may be translational or rotational.

Joint replacement

Hemi-arthroplasty

In this operation, only one-half of the joint is replaced, leaving half of the joint intact. It is normally the natural socket – for example, the acetabulum – that is left untouched. The most common example is following fracture of the femoral neck in the elderly. Such patients usually have low demand on the joint, and the hemi-arthroplasty (Fig. 27.10) gives adequate function without risking many of the complexities of a total hip replacement.

Total joint replacement

This entails resurfacing of both sides of a joint (Fig. 27.11). The choice of materials for the weight-bearing surfaces varies, depending on the joint and prosthesis in question. Currently, metal against a high-density polyethylene is the most common, although new prostheses involving metal and ceramics surfaces have been developed for use in young people (Fig. 27.12). Fixation of the implants may be with cement, or by encouraging bone to grow into or onto the surface of the implant. In small joints, such as those of the hand in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, silastic may be used as a buffer or spacer between the two joint surfaces.

Arthrodesis

Any residual cartilage is removed down to bleeding cancellous bone before the joint is rigidly fixed resulting in complete loss of movement (Fig. 27.13). Small joint fusions of toes and fingers are the most common examples. Fusion of a large joint, such as the hip or knee, will have a significant effect on mobility and will add additional stress on the joints above and below. Thus, pre-existing OA in the joints either proximal or distal to the joint being considered for fusion is a relative contraindication.

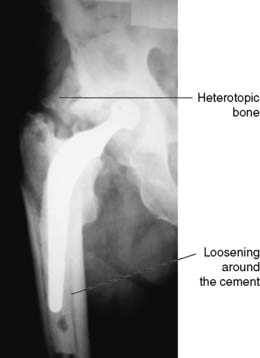

Overview of joint replacement surgery

Knee and hip replacements are the most common procedures, although shoulder, elbow, ankle, wrist and finger replacements may all be performed. With regard to the knee, there has also been a move away from traditional total joint replacement towards replacing that part of the joint affected by OA (Figs 27.14 and 27.15). These advances permit less invasive surgery and quicker recovery. Successful joint replacement surgery is associated with low infection and revision rates for prosthetic failure: ideally, less than 95% at 10–15 years (Figs 27.16 and 27.17). Revisional joint replacement surgery is more complex and associated with greater rates of complications and further device failure. Postoperative infection is divided into early and late. Early infections are usually purulent, occur within the first few weeks, and may be eradicated with early debridement and appropriate antibiotics, but may necessitate removal of the prosthesis. Late infection is usually due to more indolent organisms such as Staph. epidermidis, may follow a bacteraemia or colonization at the time of implantation, and often presents as early loosening which leads frequently to revisional surgery.

Fig. 27.15 A normal knee replacement, showing the resurfacing of the femur with a femur-shaped component.

Overview of arthroscopic surgery

• repair: menisci in the knee and the rotator cuff in the shoulder

• stabilization of unstable joints: the recurrently dislocating shoulder

• joint fusion: ankle, subtalar joint

• ligament reconstruction: anterior cruciate ligament.

• debridement – removal of infected tissue, loose or impinging bone.

Paediatric orthopaedic surgery

Dysplastic disease of the hip (DDH)

This is more common in breech deliveries, the first-born and females. It is due to inadequate development of the hip joint (Fig. 27.18), and presents with varying severity. When diagnosed in the newborn, milder forms in which the femoral head has a tendency to sublux from the acetabulum, are best treated using a ‘harness device’ that allows freedom of movement while holding the femoral head in the joint. More severe forms, where there is actually fixed dislocation, may require operative reduction and occasionally osteotomies.

The upper limb

The shoulder

Anterior dislocation

Anterior shoulder dislocation is the commonest form of dislocation, and can be associated with or without fracture (Fig. 27.19). The cause of an anterior dislocation is often traumatic. Treatment involves immediate reduction with analgesia and sedation using Kocher’s, Milche’s or Hippocratic methods. Patients require to be immobilized in a sling and a check radiograph is mandatory to confirm reduction and exclude a fracture. Instability following shoulder dislocation is common in young males and in this group of patients an arthroscopic examination and stabilization may be required if there is a high risk of recurrence.

The lower limb

Trauma and fractures

General approach

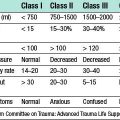

The initial assessment and resuscitation of the (multiply) injured patient follows the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines (Table 27.3) Management of the injured patient requires a team approach, and often entails joint care by a number of different specialties, from the time of initial resuscitation in the accident and emergency department right through to the definitive treatment of each injury. Certain patterns of injury can be anticipated. For example, patients who fall from a height and land on their feet may be expected to have sustained an injury to calcaneus, tibial plateau, hip and pelvis. At impact, patients tend to fall forward, often leading to spinal fractures.

| Primary survey | |

| A | Airway with C-spine control |

| B | Breathing and ventilation |

| C | Circulation and haemorrhage control |

| D | Disability (neurological evaluation) |

| E | Exposure and environment |

| Secondary survey | |

| Once the resuscitation efforts are well established and the vital signs are normalising, the secondary survey can begin. This involves a complete history and physical examination, including the reassessment of all vital signs. | |

Examination

Careful examination of each injured limb includes:

• Skin. Ascertain whether any skin breaks communicate with any underlying fracture.

• Circulation. The most common cause of absent pulses is kinking or compression of the artery by the fracture. Often, a reduction of the fracture (realigning the fracture into the anatomical position) or application of traction results in the return of perfusion.

• Nerves. Certain injuries may have a high associated risk of neurological injury, manifest by loss of power and/or sensation. For example, the axillary nerve is at risk from shoulder fracture dislocation and its integrity should be documented prior to reduction (see Fig. 27.19).

• Joint above and below. Often fractures can involve the joint immediately above or below. A complete examination of these joints is required as it may influence definitive treatment of the injury.

Fracture management

Classification

Fractures are usually classified by:

• whether they are in communication with the skin surface (open or compound) or not (closed)

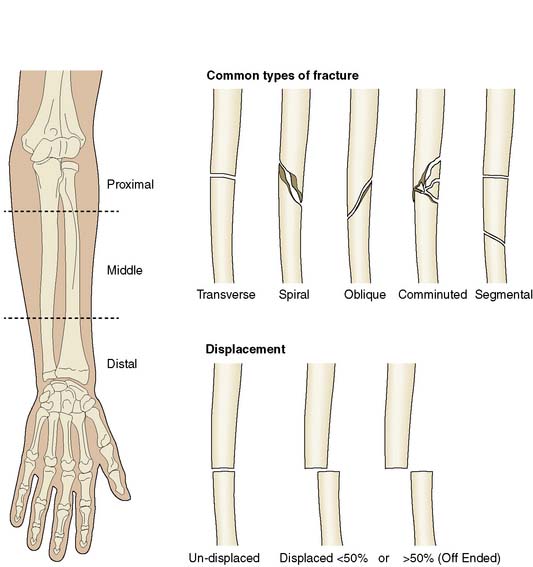

• their appearance on X-ray: for example, comminuted (in multiple pieces, Fig. 27.20), spiral (where the fracture curves in a large spiral around the long axis of the bone) or transverse (straight across the bone, Fig. 27.21) This appearance usually correlates with the mechanism of injury – a twisting injury tends to cause a spiral fracture for example.

• anatomical site: for example, intra-articular (involving the joint surface, Fig. 27.22), metaphyseal, epiphyseal or diaphyseal.

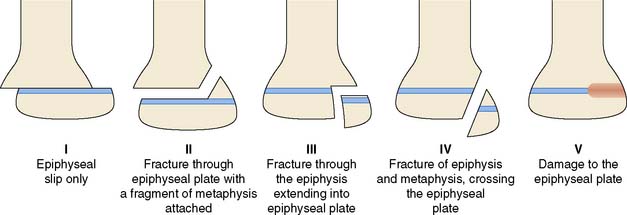

Children

Fractures often behave differently in children. Because their bones are more pliable, children may suffer from greenstick fractures, in which the cortex of the bone does not break but bends instead. Fractures may also affect the growth plate (epiphysis) of the bone, leading to problems with slowing of the growth of the bone (growth arrest) or deformity of the growing bone (Fig. 27.23). Generally, fractures heal much more quickly in children.

Compound fractures

• removal of all the damaged and dead tissue

• thorough cleaning of the wound, with at least 3 litres of fluid depending on the degree of contamination (‘the solution to pollution is dilution’)

• stabilization of the fracture to realign the bones to their anatomical position. Depending on the degree of contamination and soft tissue coverage, this may be by definitive or temporary fixation. Temporary external fixators are often attached by means of pins to the bones either side of the fracture site to allow access to the wound while imparting stability.

Operative treatment

This involves the use of devices that are broadly divided into those that remain external to the skin (see above) and those that are internal (screws, plates and nails, Fig. 27.24). The details of their use are beyond the scope of this book but depend on fracture type, site and morphology. Some devices are ‘dynamic’, in that they allow controlled collapse of the fracture, leading to compression of the bone ends and early weight bearing (Fig. 27.25).

Some specific fractures

Fractures of the femoral neck

• extracapsular, occurring outside the margins of the joint capsule, particularly the metaphysis of the femur

• intracapsular, involving the femoral neck within the capsule.

This differentiation is important because blood reaches the femoral head via the capsule and runs along the femoral neck. Extracapsular fractures are normally reduced and stabilized using a pin and plate system, commonly known as a dynamic hip screw (DHS), which allows sliding and impaction of the fracture site as the patient walks. Without these there is the risk of a malunion occurring (Fig. 27.26).

Undisplaced intracapsular fractures are pinned commonly in the hope that the blood supply to the femoral head has been preserved and avascular necrosis of the femoral head will not develop. Displaced intracapsular fractures are treated frequently with joint replacement. In older, -less active patients, this is often a hemi-arthroplasty (see Fig. 27.11). In this operation, only one-half of the joint is replaced, leaving the natural socket( the acetabulum) untouched. Such patients usually have low demand on the joint, and the hemi-arthroplasty gives good function without risking many of the complexities and complications associated with a total hip replacement. Younger patients and those expected to rehabilitate to a higher level of activity usually receive a total hip replacement.