11 The abdominal wall and hernia

Umbilicus

Developmental abnormalities

Persistent vitello-intestinal duct

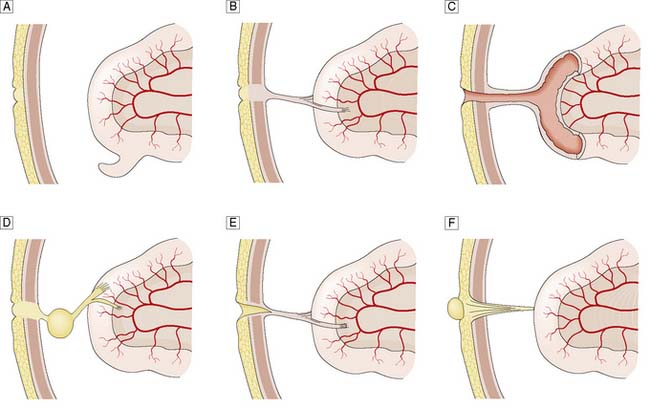

The vitello-intestinal duct runs in intrauterine life from the apex of the midgut loop to the yolk sac. It is normally obliterated long before birth, but part of it may persist as a Meckel’s diverticulum on the antimesenteric border of the ileum. Rarer abnormalities include persistence of a band attaching the umbilicus to a Meckel’s diverticulum or a loop of ileum; a patent communication (fistula) between the ileum and umbilicus; an encysted portion of the duct that does not connect with the ileum (enterocystoma); an umbilical sinus; and a persistent umbilical portion of the duct, which forms a polypoidal raspberry-like tumour of the umbilicus (enteroteratoma) (Fig. 11.1). Symptomatic remnants may have to be excised, although a broad-based Meckel’s diverticulum is usually left alone if found incidentally at laparotomy. Persisting bands can cause intestinal obstruction.

Abdominal hernia

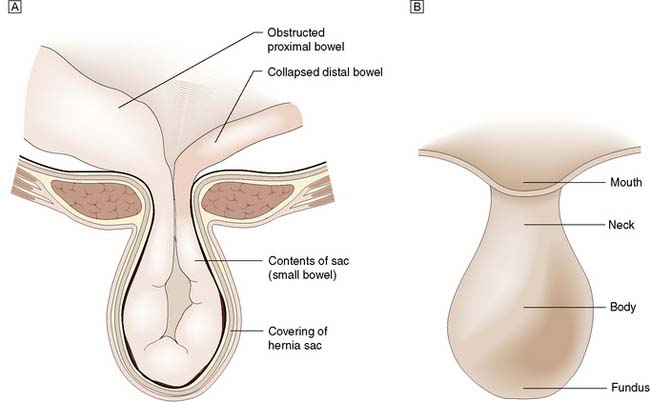

A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a cavity’s contents, through a weakness in the wall of the cavity, taking with it all the linings of the cavity, although these may be markedly attenuated (Fig. 11.2). Hernias of the abdominal wall are common. Multiple factors contribute to the development of hernias. In essence, hernias can be considered design faults, either anatomical or through inherited collagen disorders, although these two factors work together in the majority of patients. Hernias may exploit natural openings such as the inguinal and femoral canals, umbilicus, obturator canal or oesophageal hiatus, or protrude through areas weakened by stretching (e.g. epigastric hernia) or surgical incision. In addition to these ‘weak’ anatomical areas, the collagen make up of the tissues, especially the Type I to III collagen ratio is also important. Type I imparts the strength to the tendon or fascia, Type III provides elastic recoil to the tissue. The Type I/III collagen ratio varies between individuals but is constant in all the fascia of a particular individual. Hernias can be considered as a disease of collagen metabolism.

The hernia is immediately invested by a peritoneal sac drawn from the lining of the abdominal wall (Fig. 11.2). The sac is covered in turn by those tissues that are stretched in front of it as the hernia enlarges (i.e. the coverings). The neck of the sac is the constriction formed by the orifice in the abdominal wall through which the hernia passes. A hernia may contain any intra-abdominal structure but most commonly contains omentum and/or small bowel. A hernia may involve only part of the circumference of the bowel (Richter’s hernia), a Meckel’s diverticulum (Littré’s hernia) or an incarcerated appendix (Amyand’s hernia). A sliding inguinal hernia is defined as one in which a viscus forms a portion of the wall of the hernia sac. Most commonly, the viscus involved is caecum, sigmoid colon or urinary bladder. In the early stages of a hernia, sometimes the hernial contents are pre-peritoneal fat only, such as a lipoma of the cord which can mimic an inguinal hernia.

Summary Box 11.1 Hernia

• A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of a cavity’s contents through a weakness in the wall of the cavity, but takes with it all the linings of the cavity

• Hernias of the abdominal wall are common and may exploit natural openings or weak areas caused by stretching or surgical incisions in association with a defect in collagen metabolism

• Abdominal hernias have a peritoneal sac, the neck of which is often unyielding and constitutes a potential source of compression of the hernial contents

• Hernia may be classified as reducible or irreducible, and the contents (e.g. bowel) may become obstructed or strangulated

• Strangulation denotes compromise of the blood supply of the contents and its development significantly increases morbidity and mortality. The low-pressure venous drainage is occluded first and then the arterial supply becomes occluded, with the development of gangrene.

Inguinal hernia

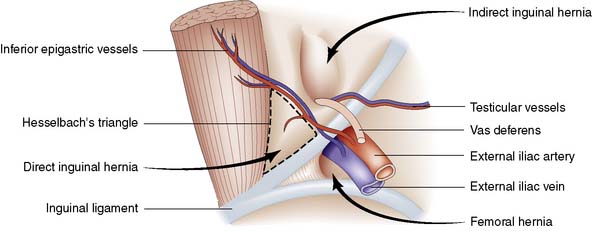

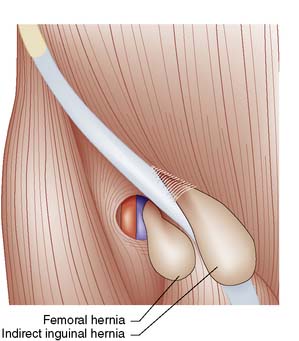

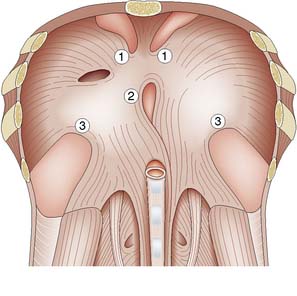

Groin hernias account for three-quarters of all abdominal wall hernias, and inguinal herniorrhaphy is one of the most frequently performed general surgical procedures. The most common types of groin hernia are indirect inguinal (60%), direct inguinal (25%) and femoral (15%) (Fig. 11.3). Most (85%) groin hernias occur in males. Inguinal hernias occur in 1–3% of all newborn males. The incidence in premature infants is 30 times that seen at term. In early life, an indirect inguinal hernia is by far the most common variety. After middle age, weakness of the abdominal musculature leads to an increasing incidence of direct inguinal hernias. Femoral hernias are relatively more common in females (possibly because of stretching of ligaments and widening of the femoral ring in pregnancy), but an indirect inguinal hernia is still the most common type of groin hernia in women.

Surgical anatomy

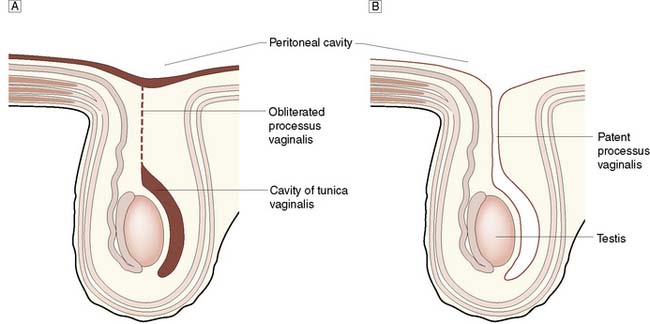

The inguinal canal is an oblique passage in the lower anterior abdominal wall, through which the spermatic cord passes to the testis in the male, or the round ligament to the labium majus in the female. The processus vaginalis traversing the canal is normally obliterated at birth, but persistence in whole or in part presents an anatomical predisposition to an indirect inguinal hernia (Fig. 11.4). The openings of the canal are formed by the internal and external rings. The internal (deep) inguinal ring is an opening in the transversalis fascia, which lies approximately 1 cm above the mid-inguinal point (midway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine). The internal inguinal ring is bounded medially by the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 11.3). The inguinal canal ends at the external (superficial) inguinal ring, which is an opening in the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle just above and medial to the pubic tubercle. At birth, the internal and external rings lie on top of each other, so that the inguinal canal is short and straight; with growth, the two rings move apart so that the canal becomes longer and oblique.

Indirect inguinal hernia

Clinical features

The hernia forms a swelling in the inguinal canal, which may extend into the scrotum. It is often readily visible when the patient stands or is asked to cough. However, as the population becomes fatter, and patients tend to present earlier with symptoms or a small swelling, the diagnosis may not be so obvious on inspection of the groin. However, look for signs of asymmetry between the two groins. While bilateral inguinal hernias are not unusual, it is unusual for both hernias to be of similar size (Fig. 11.5). An inguinal hernia, which passes into the scrotum, passes above and medial to the pubic tubercle, in contrast to a femoral hernia, which bulges below and lateral to the tubercle (Fig. 11.6). Again, in more obese patients, such landmarks can be difficult to palpate with confidence. A cough impulse is normally palpable, and bowel sounds can often be heard within the hernia on auscultation. If there is no visible swelling, a cough impulse is sought with the patient standing.

Direct inguinal hernia

Direct hernias are due to weakness of the abdominal wall and may be precipitated by increases in intra-abdominal pressure (e.g. obstructive airways disease, prostatism or chronic constipation). The hernia protrudes through the transversalis fascia in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. The defect is bounded above by the conjoint tendon, below by the inguinal ligament, and laterally by the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 11.3). These boundaries mark the area known as Hesselbach’s triangle. The hernia occasionally bulges through the external (superficial) inguinal ring, but the transversalis fascia cannot stretch sufficiently to allow it to descend down into the scrotum. The sac has a wide neck, so that the hernia seldom becomes irreducible, obstructs or strangulates. As shown in Figure 11.3, the neck of the sac of a direct inguinal hernia lies medial to the inferior epigastric vessels, whereas that of an indirect hernia lies lateral to them. A combined indirect and direct hernia may occur on the same side (pantaloon or saddle-bag hernia), with sacs straddling the inferior epigastric vessels.

Management of uncomplicated inguinal hernia

Adults with a symptomatic inguinal hernia should be offered surgery. Open mesh repair or laparoscopic mesh repair aims to reduce postoperative pain to a minimum, enabling most procedures to be undertaken as day cases EBM 11.1. Inguinal hernias can be controlled by a truss, but this is uncomfortable and is now seldom indicated, as repair using local or regional anaesthestic techniques can be employed in higher-risk patients.

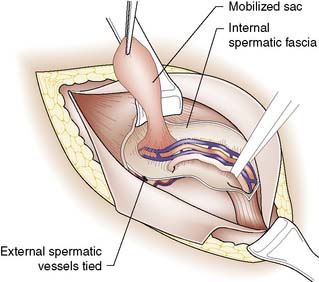

Indirect inguinal hernia

The first step in the open approach is to open the inguinal canal, free the hernial sac from the spermatic cord (Fig. 11.7) and excise it after transfixing and ligating its neck. Simple excision of the sac (herniotomy) is all that is needed in young children. In older children and adults, the internal ring is usually stretched and widened, and therefore after herniotomy it is necessary to tighten the deep ring and/or strengthen the posterior wall with a mesh (herniorrhaphy or hernioplasty). Suture repair alone is rare in developed countries in adults, but still has a place in the repair of groin hernias in adolescents (a rare age for presentation of groin hernias).

Direct hernia

In a direct hernia, the sac, following mobilization from the spermatic cord, is not normally excised and it is simply invaginated by sutures placed in the transversalis fascia. Insertion of a synthetic mesh is currently used to reinforce the posterior wall of the inguinal canal EBM 11.2.

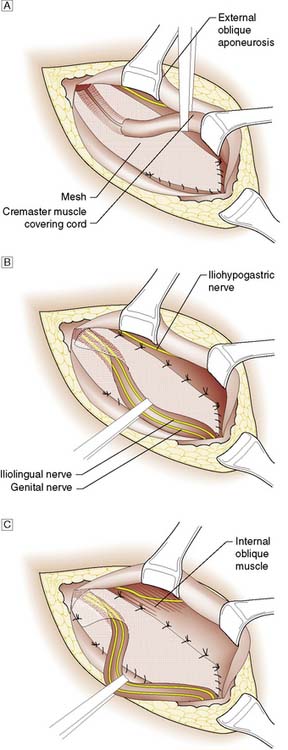

The most common surgical procedure now performed is the Lichtenstein open tension-free repair, which involves the insertion of a synthetic mesh underneath the spermatic cord (Fig. 11.8). The mesh is secured to the aponeurotic tissue overlying the pubic bone medially, the inguinal ligament inferiorly, and the internal oblique aponeurosis and conjoint tendon superiorly. Laterally, the mesh is divided and its two sides wrapped around the spermatic cord and sutured in place.

Femoral hernia

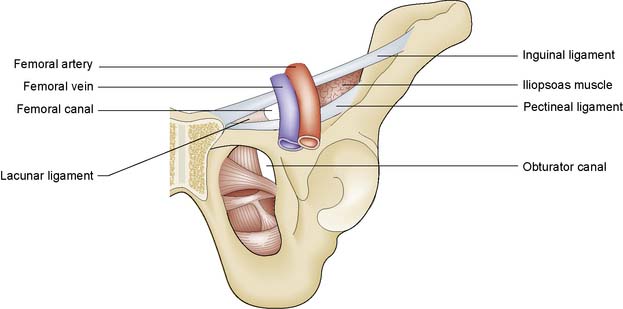

A femoral hernia projects through the femoral ring and passes down the femoral canal. The ring is bounded laterally by the femoral vein, superiorly by the inguinal ligament, medially by the lacunar ligament, and inferiorly by the superior ramus of the pubis and the reflected part of the inguinal ligament (pectineal ligament of Astley Cooper) (Fig. 11.9). As the hernia enlarges, it passes through the saphenous opening in the deep fascia of the thigh (the site of penetration of the long saphenous vein to join the femoral vein) and then turns upwards to lie in front of the inguinal ligament. The hernia has many coverings and may be deceptively small, sometimes escaping detection. It frequently contains omentum or small bowel, but the urinary bladder can ‘slide’ into the medial wall of the sac.

Surgical repair of femoral hernia

A femoral hernia is particularly likely to obstruct and strangulate (indeed 40% of such hernias present this way), and therefore surgical intervention is indicated EBM 11.3. As with inguinal hernia, repair can be carried out under local or general anaesthesia.

Summary Box 11.2 Groin hernias

• Indirect inguinal hernias comprise 60% of all groin hernias and commence at the deep inguinal ring, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels

• Direct inguinal hernias account for 25% of all groin hernias and bulge through a weakness in the back wall of the inguinal canal, medial to the inferior epigastric vessels. They rarely obstruct or strangulate

• Indirect inguinal hernias may pass down within the coverings of the spermatic cord to the scrotum; direct hernias do not descend into the scrotum

• Asymptomatic inguinal hernias do not have to be repaired, especially in the elderly

• Femoral hernias account for 15% of all groin hernias and pass through the femoral canal, emerging below and lateral to the pubic tubercle (in contrast to inguinal hernias, which pass medially to the tubercle and may descend to the scrotum)

• Femoral hernias are often small and easy to miss on clinical examination, but are prone to obstruct and strangulate.

Ventral hernia

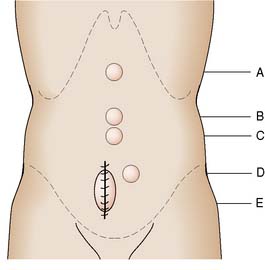

Ventral hernias occur through areas of weakness in the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 11.10): namely, the linea alba (epigastric hernia), the umbilicus (umbilical and paraumbilical hernia), the lateral border of the rectus sheath (Spigelian hernia), and the scar tissue of surgical incisions (incisional hernia). Such incisions include scars from laparoscopic surgery, the so-called port-site hernia.

Para-umbilical hernia

This hernia is caused by gradual weakening of the tissues around the umbilicus (Fig. 11.11). It most often affects obese multiparous women, and passes through the attenuated linea alba just above or below the umbilicus. The peritoneal sac is often preceded by the extrusion of a small knuckle of extraperitoneal fat through the linea alba. The hernia gradually enlarges, the covering tissues become stretched and thin, and eventually loops of bowel may become visible under parchment-like skin. The sac is often multilocular and may be irreducible because of adhesions that form between omentum and loops of bowel. The skin may become reddened, excoriated and ulcerated, and rarely an intestinal fistula may even develop.

Incisional hernia

Incisional hernias occur after 5% of all abdominal operations. Over half of incisional hernias occur in the first 5 years after the original surgery. Midline vertical incisions are most often affected, and poor surgical technique, wound infection, obesity and chest infection are important predisposing factors, in addition to the collagen metabolism status of the patient. The diffuse bulge in the wound is best seen when the patient coughs or raises the head and shoulders from a pillow, thereby contracting the abdominal muscles (Fig. 11.12). Strangulation is rare, but surgical repair is usually advised.

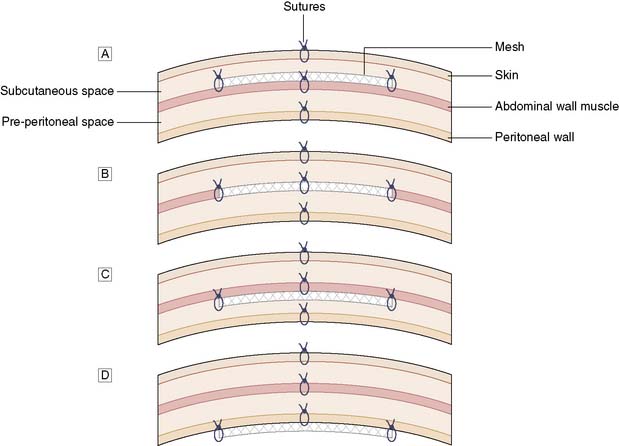

Again, open or laparoscopic mesh repair is possible. At open surgery, the mesh can be inserted as an onlay, inlay, sublay or intraperitoneal position (Fig. 11.13). The sublay operation is associated with the lowest incidence of wound complications and recurrence of the hernia. Many incisional hernia wounds are cosmetically poor, so laparoscopic surgery for cosmesis is not so clear cut. However, laparoscopic surgery is associated with less pain, shorter hospital stay and more rapid return to activities. However, it is difficult to restore the normal anatomy by bringing the muscles together again at laparoscopic surgery, and thus such an approach is mainly used for smaller incisional hernias.

Rare external hernia

• A Spigelian hernia occurs through the linea semilunaris at the outer border of the rectus abdominis muscle. Treatment is surgical, as the hernia is liable to strangulate

• A lumbar hernia forms a diffuse bulge above the iliac crest between the posterior borders of the external oblique and latissimus dorsi muscles. It seldom requires treatment

• An obturator hernia is a rare hernia that is more common in women and passes through the obturator canal. Patients may present with knee pain owing to pressure on the obturator nerve; however, the diagnosis is frequently made only when the hernia has strangulated and is discovered at laparotomy.

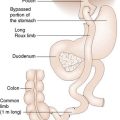

Internal hernia

Herniation of the stomach through the oesophageal hiatus in the diaphragm (hiatus hernia) is a common cause of internal herniation and is considered in Chapter 13. A variety of cul-de-sacs and peritoneal defects resulting from rotation of the bowel and other abnormalities of development may be responsible for the entrapment of bowel and acute intestinal obstruction. For example, herniation may occur through the foramen of Winslow (opening of the lesser sac) and through various openings in the diaphragm, including the oesophageal hiatus (Fig. 11.14). In addition, bowel operations, such as the development of a Roux loop can lead to ‘iatrogenic’ sites for internal hernia formation.

Complications of hernia

Strangulation

The patient complains of pain in the hernia and usually has features of intestinal obstruction (vomiting, abdominal distension). The skin overlying the hernia is red, warm to touch and tender, the cough impulse is lost, and there may be increasing evidence of circulatory collapse and sepsis. In a Richter’s hernia, only part of the circumference of the bowel is strangulated, and there may be no evidence of intestinal obstruction. Strangulation is the main risk factor for death in such cases EBM 11.3.