Chapter 28 Posterior Approach to the Lumbar Spine

MUSCULAR STRUCTURES FOR POSTERIOR APPROACH IN L-SPINE

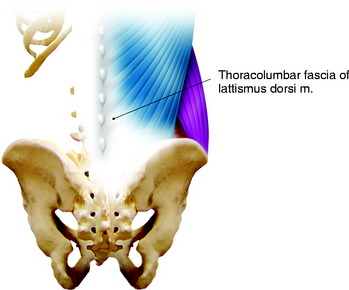

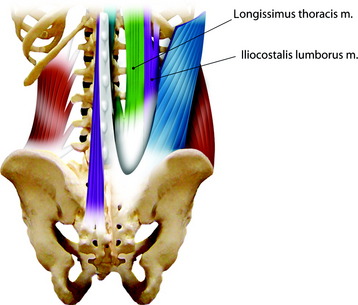

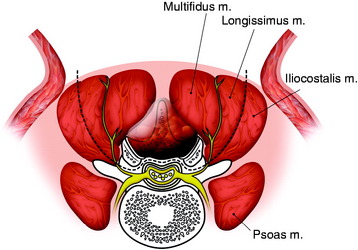

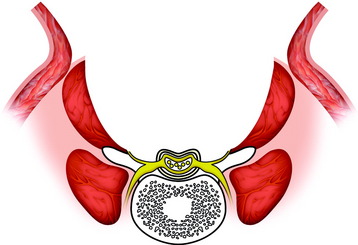

The muscle groups on the dorsal side of the lumbar spine are covered with thoracolumbar fascia. This fascia is the extension of the latissimus dorsi (LD) muscle (Fig. 28-1). Under the LD muscle fascia, the erector spinae muscle groups are located. They are longitudinally arranged with medial, middle, and lateral components (Fig. 28-2). At the upper lumbar level, the serratus posterior inferior muscle is arrayed from the horizontal direction.

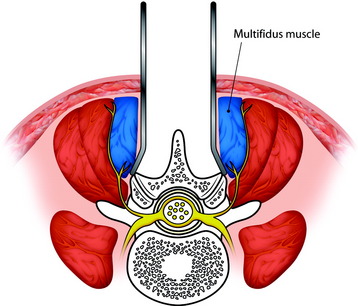

There are cleavage planes between these three groups of muscles. The dissection can be performed more easily between the multifidus muscle and the longissimus muscle than between the longissimus muscle and the iliocostalis muscle (Fig. 28-3).

DEVELOPING THE PLANE DURING MUSCLE DISSECTION

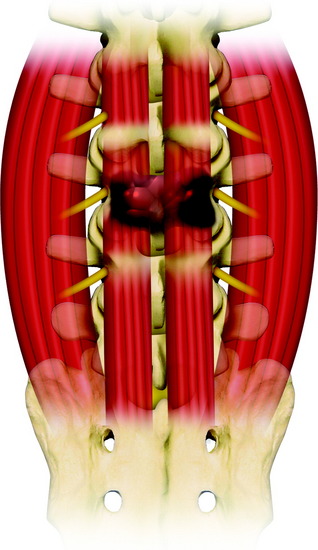

A natural cleavage plane between the multifidus and the longissimus part of the sacrospinalis muscle is present in most of the operated cases. There is a fibrous separation between the two muscular parts. The mean distance between the level of the cleavage plane and the midline was 4 cm (2.4–5.5 cm).1 Small arteries and veins were present, precisely at the level of the cleavage plane. For the dissection between multifidus and longissimus, first, the superficial muscular fascia is opened near the midline, exposing the posterior aspect of the sacrospinalis muscle. Next, the location of the muscular cleft can be found by identifying the perforating vessels leaving the anatomical intermuscular space. The muscular plane can be confirmed with fat tissue. Further dissection leads to the pedicle. The multifidus muscle volume becomes wider from the upper lumbar level to the lumbosacral junction (Figs. 28-4 and 28-5).

NEURAL STRUCTURES IN POSTERIOR APPROACH

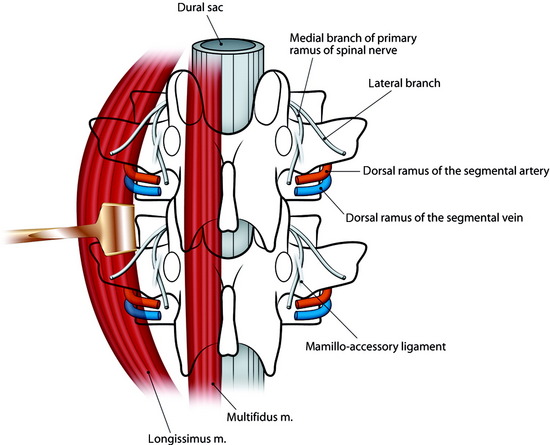

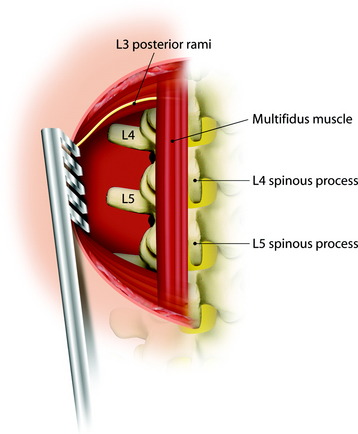

The posterior ramus of the spinal nerve root is divided into two branches, medial and lateral (Fig. 28-6). The lateral branch of the posterior ramus of the spinal nerve lies in the fascial plane between longissimus muscle and multifidus muscle (Fig. 28-7). The medial branch of the posterior ramus of the spinal nerve runs into the multifidus muscle belly.

Denervation during a dorsomedian approach to the thoracolumbar spine may cause postoperative atrophy of the deep back muscles. The ensuing instability of the spine with poor clinical results, perhaps as a result of such muscle loss, has been observed in 11.7% of cases.2 Specifically, this complication may be caused by damage to the medial branches of the posterior rami of the spinal nerves during lateral retraction of the muscles.

In the thoracolumbar spine the medial branch of the posterior ramus of the spinal nerve is subject to ligamentous fixation by the strong fibers of the mammillo-accessory ligament, which extends between the mammillary process and the accessory process inferolateral to the superior articular process. When the extent of dissection of the dorsomedian approach to the thoracolumbar spine is enlarged laterally to the articular processes by retracting the paraspinous muscles, the medial branches of the posterior rami of the spinal nerves are endangered (Fig. 28-8). Postoperative pain as well as dynamic instability beyond the corresponding segments could result. To prevent injury to the medial branches of the posterior rami of the spinal nerves, the midline posterior surgical approach to the thoracolumbar spine should not be enlarged laterally to the articular processes.3

VASCULAR SUPPLY TO THE POSTERIOR BACK MUSCLE3

The posterior branch of the segmental artery in the lumbar region arises lateral to the intervertebral foramen and runs dorsocaudal, inferior to the spinal nerve and lateral to the superior articular process of the vertebra below (see Fig. 28-6). In the interarticular space, that is, lateral to neural foramen, it divides into the lateral and intermediate branches, which penetrate the deep back muscles, and a medial branch, which pursues a dorsal course close to the bone and anastomoses with the contralateral artery posterior to the spinous process. The posterior branch of the segmental artery supplies the deep back muscles, articular processes, laminae, and spinous processes, as well as related ligaments. Segmental arteries freely anastomose with each other over several segments and provide an arterial supply for the dorsal parts of the vertebrae and their ligaments.

MIDLINE APPROACH VS. PARAMEDIAN APPROACH

At all levels the access depth is longer with the paramedian approach (L1–2: 8.0 cm, L2–3: 8.3 cm, L3–4: 8.6 cm, L4–5: 8.6 cm) than with the midline approach (L1–2: 6.3 cm, L2–3: 6.5 cm, L3–4: 6.9 cm, L4–5: 7.5 cm).4 At all studied levels the angle of vision is larger in the paramedian approach (L1–2: 48 degrees, L2–3: 45 degrees, L3–4: 43 degrees, L4–5: 36 degrees) than in the midline approach (L1–2: 32 degrees, L2–3: 26 degrees, L3–4: 25 degrees, L4–5: 23 degrees).4 A larger angle will provide a deeper visualization into the intervertebral foramen. In the lower lumbar spine, the angles for both approaches are smaller because of the deeper location of the intervertebral foramen and the smaller muscle retraction possible on this level.5 In this situation, the gain achieved by the paramedian approach may be even more significant. When the extent of surgical resection is planned onto the pedicle, the paramedian approach provides a better angle of vision and is less likely to injure the paraspinal muscles and their innervation.

SURGICAL APPROACH TO TUMORS AT POSTERIOR ELEMENT OF L-SPINE (L3 LEVEL)

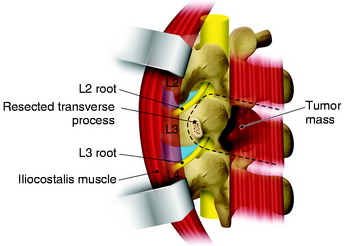

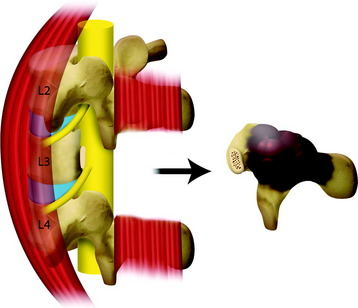

Tumors involving the lumbar spine are less common than those involving the thoracic spine. In regard to metastatic tumors, only 20% of spinal metastasis involves the lumbar spine.6 Tumors arising from the posterior element are rare. They can involve the laminae, spinous processes, superior articular processes, and pedicles. When the tumor mass is confined to the laminae and facets, en bloc removal can be attempted. For en bloc removal of the posterior element mass, the surrounding soft tissue should be removed at the same time. In this situation, the paraspinal approach is more favored than the midline approach. The paraspinal approach is performed with the splitting of the paraspinal muscles. The dissection plane can be made between the multifidus muscle and longissimus muscle. Another plane is searched for between the longissimus muscle and the iliocostalis muscle. When the tumors are located in the posterior element and invade the posterior muscles, wide excision including the paraspinal muscle may be possible (Fig. 28-9).

Skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised on the midline from T12 to S1 and reflected bilaterally to expose the whole width of the erector spinae muscles. The fascial incision is made on the midline and reflected the same width as the subcutaneous tissue. Then the muscle dissection is performed at the junction of the longissimus muscle and the iliocostalis muscle on both sides (see Fig. 28-9). Medially retracted muscle groups are the multifidus muscle and longissimus muscle, which are divided horizontally to the level of the L2–3 facet and L3–4 facet (Fig. 28-10). The divided muscle should include the mass with sufficient resection margin. Further dissection to the deeper level reaches to the posterior surface of the transverse process (see Fig. 28-7). The transverse process is removed from the base with a Kerrison rongeur. Then the pedicle and intervertebral foramen are seen from the oblique view. The lower margin of the pedicle is dissected, and the exiting nerve root is searched and dissected from the surrounding fat tissue (Fig. 28-11). After the course of the exiting nerve root is confirmed, the pedicular resection is attempted with a drill or Kerrison rongeur. If the surgeons are accustomed to using the threadwire saw, it may be helpful as in the thoracic spine spondylectomy. The lateral margin of the tumor mass is confined with the muscle dissection and pedicle resection. The upper margin is resected with disarticulation of the facet joint above and below (Fig. 28-12). After the en bloc removal, a portion of the iliocostalis muscle is left and a large muscle tissue defect is seen (Fig. 28-13). The fascia should be closed tightly, and the drain is left in the tissue defect. The skin and subcutaneous tissue are closed layer by layer.

Case I

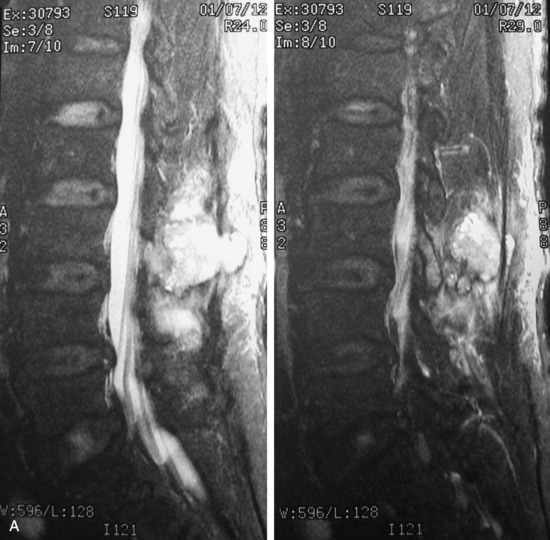

L3 POSTERIOR ELEMENT METASTASIS OF RENAL CELL CARCINOMA

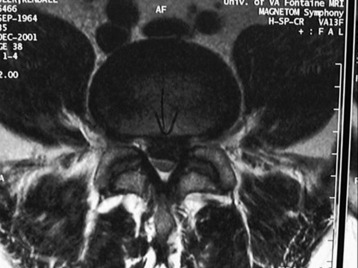

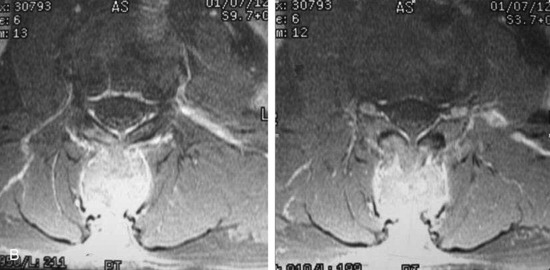

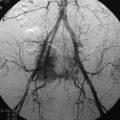

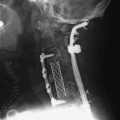

A 62-year-old male patient presented to the neurosurgical department because of back pain that radiated to both buttocks that had persisted for 3 months. The simple radiographical work-up did not show any abnormality. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a low signal mass (T1-weighted image) was detected from the posterior side of the dural sac (Fig. 28-14, A and B). He had been diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma and had been treated with nephrectomy and chemotherapy. A spine operation was performed because the spine metastasis of renal cell carcinoma is radio-resistant tumor. With the patient in a prone position, posterior decompression was performed at the L3 and L4 levels. After complete decompression of the dural sac, posterior instrumentation was performed from L2 to L4 with a pedicle screw system (Fig. 28-14, C).

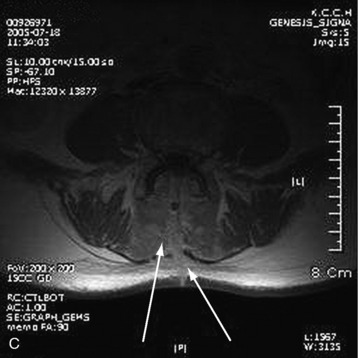

Case II

A 63-year-old male patient presented with low back pain and radiating pain in both legs. MRI showed multiple abnormal signal lesions involving the vertebral body and spinous process. An epidural mass was seen along the posterior surface of the dural sac at the L3 level (Fig. 28-15, A). The operation was performed to make the pathological diagnosis and for dural sac decompression. With a posterior approach, the L3 spinous process and bilateral lamina were removed. The bilateral facet joints were saved. The epidural mass was removed from the dural sac. The pathological diagnosis was lymphoma. Chemotherapy was carried out. Follow-up MRI 6 months later indicated that the dural sac was fully decompressed, and fibrotic scar tissue was observed (Fig. 28-15, B and C).