Chapter 26 Posterior and Posterolateral Access to the Thoracic Spine

INTRODUCTION

Several surgical approaches have been developed to remove thoracic vertebral lesions from the anterior to posterolateral direction. The choice of surgical approach is decided depending on the disease entity, level of the lesion, laterality, multiplicity, presence of instability, and the necessity of reconstruction. The posterior approach provides less extensive exposure of the vertebral body than the anterior approach, but the involved anatomy is familiar to the spinal surgeons and it can be applied to patients with anesthetic risk.1

Advantages of the posterior approach over the anterior approach are as follows2,3:

With increasing bone removal, from the transpedicular approach to the costotransversectomy, and finally to the lateral extra-cavitary/lateral parascapular approach, the operative trajectory becomes more lateral to better visualize the affected vertebrae.4 In this chapter, overall review of the posterior or posterolateral approach to thoracic spine will be presented with the pertinent anatomical assessment.

MUSCULAR ANATOMY

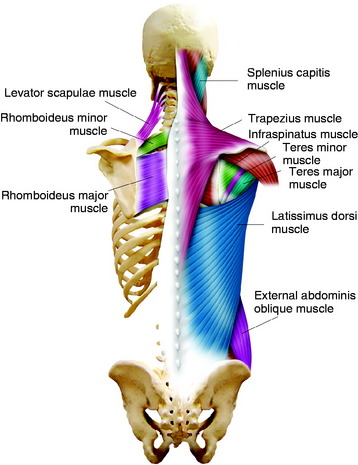

The most superficial muscle of the dorsal spine is the trapezius muscle (Fig. 26-1). The trapezius originates along the external occipital protuberance and each spinous process from C1 to T12. The insertion of the trapezius is the lateral third of the clavicle, the acromion and the scapular spine. This muscle provides the stabilization and abduction of the shoulder. Immediately deep to the trapezius muscle on the upper thoracic level lie the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and levator scapulae muscles (see Fig. 26-1). The rhomboid muscles originate from the spinous processes of the cervical and thoracic spine and insert to the ventral edge of the scapula.5 The levator scapulae muscle connects the scapula to the upper cervical vertebrae.

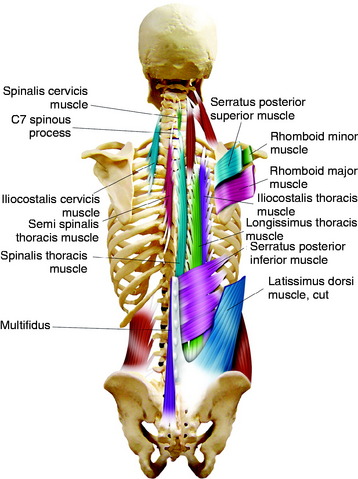

The serratus posterior superior muscle is another muscle that fixes the cervicothoracic junction area spinous processes to the lateral part of rib cage (Fig. 26-2). In the exposure of the cervicothoracic junction, the spinous process insertions of these muscles are taken down as a single group for lateral retraction.6 As these muscles are taken down, the scapula is released from its attachments to the spinous processes and rotates anterolaterally out of the operation field.

On the lower portion of the back, the latissimus dorsi muscle spans over the body. It originates from the spinous processes of the six lower thoracic vertebrae, lumbar and sacral vertebrae, and ilium, inserting onto the humerus (see Fig. 26-1).

The erector spinae muscles are a group of muscles running from the sacrum and iliac crest to the ribs or transverse process of the vertebrae. They have three separated groups: iliocostalis (lateral), longissimus (middle), spinalis (medial) (see Fig. 26-2). The iliocostalis muscle is inserted into the angles of the ribs and into the cervical transverse processes from C4 through C6. The longissimus thoracis muscles are inserted into the thoracic transverse processes and nearby parts of the ribs between T2 and T12. The spinalis muscle is largely aponeurotic and extends from the upper lumbar to the lower cervical spinous processes.

POSTERIOR THORACIC CAGE

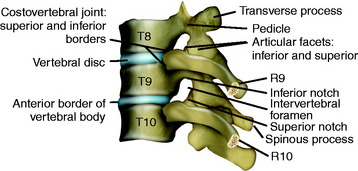

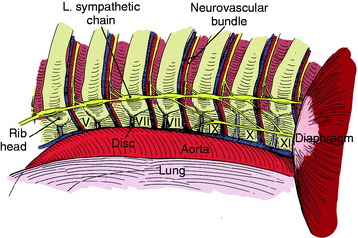

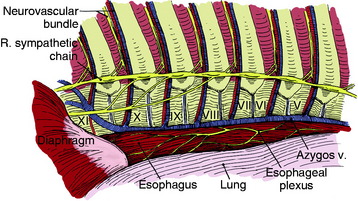

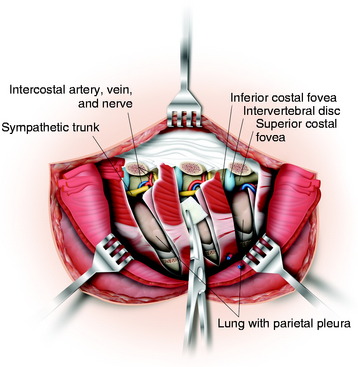

The head of a rib articulates with the adjacent parts of its own vertebral body, the vertebra above, and the intervertebral disc between them (Fig. 26-3).

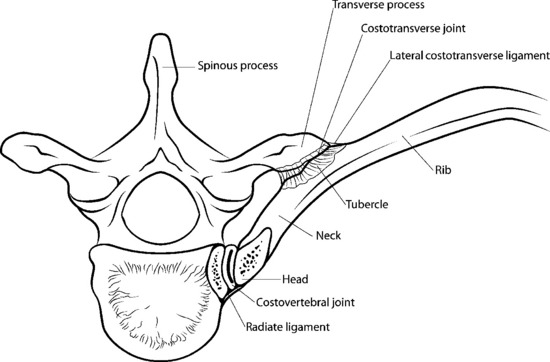

The third synovial joint is a costotransverse joint that is strengthened by superior and lateral costotransverse ligaments (Fig. 26-4). The superior costotransverse ligament joins the neck of the rib to the transverse process immediately above.

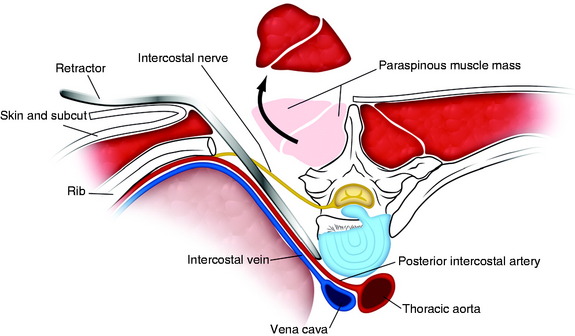

The ribs also are attached to one another through the intercostal musculature, which originates medially on each superior rib and inserts laterally on its immediately inferior rib. This strip of muscles contains the intercostal nerve, artery, and vein. Most often, the intercostal vein is most cephalad with the intercostal artery close to it but caudad (Fig. 26-5).

POSTERIOR MEDIASTINAL SPACE AND NEUROVASCULAR STRUCTURE

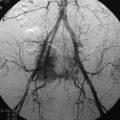

The azygos vein is lateral to the esophagus on the right side, running inferiorly to join the superior vein cava at the fourth interspace. At the point where the azygos vein turns medially, it may receive some branches, which may be divided if necessary (Fig. 26-6).

LATERAL EXTRA-CAVITARY APPROACH

The lateral extra-cavitary approach (LECA) is an extension of costotransversectomy. The more extensive rib resection provides the more ventral and wider operative view across the midline.7

It can be applied for the management of thoracic disc herniation, upper lumbar disc herniation, trauma, tumors, and inflammatory diseases involving up to three and sometimes four vertebral levels.1,8 It may not be applicable above the T4 level because of the scapula and below L4 level because of the iliac crest.

POSITIONING AND INCISION

A midline vertical incision (three levels above and three levels below) is made with a gently curved lateral portion (12–14 cm). This incision offers access to both the posterior midline and anterior vertebral body through the lateral approach (Fig. 26-7).9

MUSCLE DISSECTION

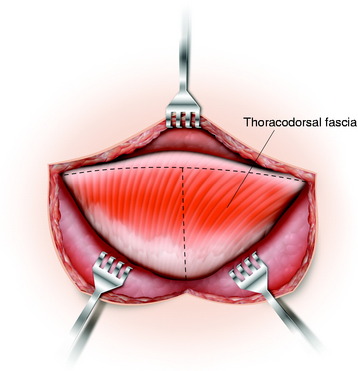

Skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised and reflected to the extended incision side. Then the thoracodorsal fascia is dissected from the midline and incised along the horizontal skin incision line. The thoracolumbar fascia appears silver to white. When it is dissected and retracted, the lateral branch of the dorsal ramus of the spinal nerve is seen to run over the surface of the muscle layer (Fig. 26-8).10

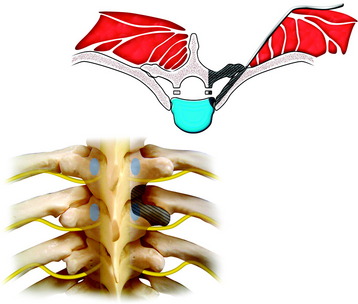

Trapezius muscle or latissimus dorsi muscle is divided with the attached fascia depending on the level of the lesion. The entire skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and fascia flap are then elevated and retracted laterally. A plane is defined at the lateral aspect of the erector spinae group, and these muscles are elevated as a layer off the ribs and are retracted medially (Fig. 26-9).

RIB RESECTION

The superior costotransverse ligaments, radiate ligament, posterior costotransverse ligament are incised with a scalpel. After the costovertebral joint is opened, the rib head is elevated out of the field. It is important to remove the rib and transverse process at the articulation to ensure full exposure (Fig. 26-10).

IDENTIFICATION OF NEURAL FORAMEN

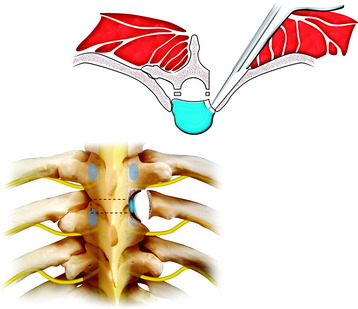

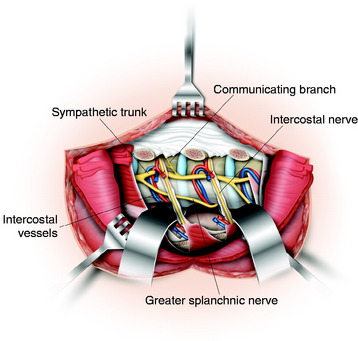

Each intercostal nerve is then traced into its respective foramen (Fig. 26-11). A ligature is placed around the nerve, which is cut 3.0 cm distal to the dorsal root ganglia, and the nerve is retracted to the dorsal side. The retracted nerve roots cause spinal cord retraction, which enables the surgeon to view the vertebral body across the midline.

When the epidural space is opened, epidural venous plexus bleeding is severe.

CORPECTOMY OR DISCECTOMY

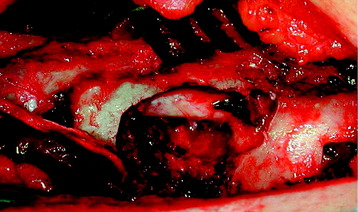

The annuli adjacent to the vertebral bodies to be removed are incised with a number 15 blade, and a punch is used to create a seat for a drill bit (Figs. 26-12 and 26-13). Using a brace and bit, the disc material and endplates are drilled out about three-fourths of the way across the vertebral body, thus ensuring that the surgeon is across the spinal canal. The posterior intervertebral disc space, about 1.0 cm ventral to the canal, is the portion to be drilled out. The intervening vertebral bone is removed using a rongeur or a high-speed drill to go deep through the vertebra. At this point, there should be at least 1 to 2 cm of bone left anteriorly and dorsal shelf posteriorly. Careful dissection of the dura-bone interface can be helpful to break up adhesions and define spicules, which may be stuck to the sac. The backward-angled curette is used to remove the posterior cortex from the ventral dura. The posterior cortex can be removed in a single piece by working primarily at the junctions of the intervertebral discs, and posterior cortex removal can be extended across the spinal canal (Fig. 26-14).

TRANSCOSTOVERTEBRAL APPROACH

Posterior surgical approaches to the thoracic spine are the transpedicular, transfacetal, costotransversectomy, and LECA. The transpedicular and transfacetal approaches are included in the transcostovertebral approach.11

Midline incision and usual posterior exposure are performed. The transverse process of the involved level is resected en bloc to uncover the costotransverse junction and to provide access to the costovertebral joint (Fig. 26-15).4

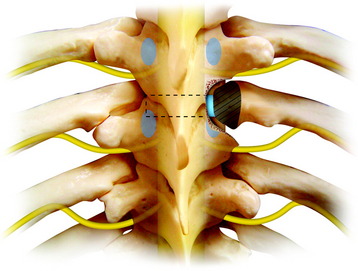

The lateral portion of the facet joint and superior half of the pedicle are removed with a drill. The thoracic pedicle can be identified by following the superior facet. The pedicle is the landmark for the inferior margin of the disc. After removing the facet and pedicle, one can reach the costovertebral joint (Fig. 26-16).

This joint is composed of the lateral end of the disc, rib head, and lateral aspects of the pedicle. From the center of the joint, the drilling is continued outward circumferentially to include immediately adjacent structures such as the posterior cortex of the rib head and lateral endplates above and below the annulus (Fig. 26-17).

This maneuver exposes the lateral and anterior aspects of the spinal cord.

COSTOTRANSVERSECTOMY

The costotransversectomy was first used for the drainage of tuberculous paraspinal abscesses in Pott’s disease.4,12 This approach provides access to the posterior and lateral aspects of the vertebrae. It extends the exposure provided by the pediculectomy by resecting the transverse process, the medial portion of the rib and rib head, the costotransversectomy, and costovertebral ligaments (Fig. 26-18).12

POSITIONING AND INCISION

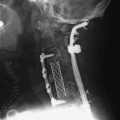

An oblique incision following the rib to be resected and extending across the midline is preferred for relatively localized lesions, such as herniated discs or neurofibroma. In more extensive lesions, and particularly in cases where a fusion procedure with instrumentation is needed, a T-shaped incision is better (Fig. 26-19) because it allows the surgeon to resect several ribs and expose the spinal column at multiple levels. The transverse limb is at the level of the vertebra to be exposed.

MUSCLE DISSECTION

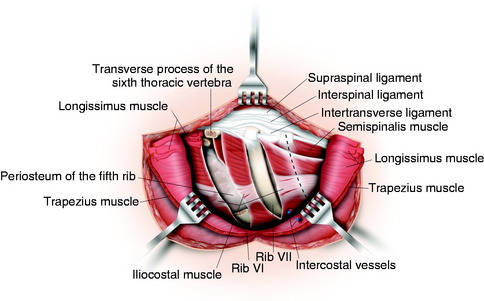

After the skin is incised, the trapezius or latissimus dorsi muscle is divided along the skin incision line to expose the underlying rib. The intrinsic muscles of the back, in accordance with the skin incision, are now first separated from the spinous processes close to the bone. The intrinsic muscles of the back are dissected with a rasp from the vertebral arches and transverse processes above and below the transverse incision. After this, the longissimus muscle is transversely dissected and retracted superiorly and inferiorly (Fig. 26-20). The ribs, laminae, facet joints, and transverse processes are visualized at this point. The proximal 5–6 cm of the selected rib is resected after stripping of the periosteal covering as well as any other soft tissues.

RIB RESECTION

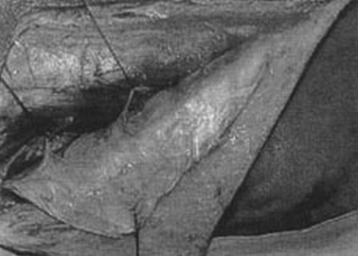

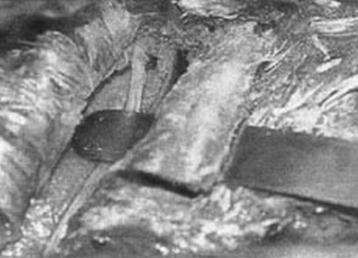

The periosteum over this rib is split with the electrocautery knife and cautiously retracted with an elevator. To begin with, the lower border of the rib is dissected subperiosteally from lateral to medial. The upper border of the rib is dissected subperiosteally from medial to lateral until the entire circumference of the rib is exposed. Medially the subperiosteal exposure is continued as far as the costotransverse articulation. Using rib cutters, the rib is initially divided laterally; the costotransverse joint is then opened with a knife, and the transverse process is exposed subperiosteally as far as the lamina. The transverse process may subsequently be separated at its base with a narrow chisel and removed with a Luer bone rongeur. The laterally separated rib is lifted from the wound bed, and the periosteum below the rib is now cautiously stripped with an elevator as far as the costovertebral articulation, sparing the neurovascular bundle lying caudal to the rib. Removal of the rib is accomplished with rotatory movements on the rib and simultaneous retraction of the costovertebral joint capsule (see Fig. 26-20).

EXPOSURE OF VERTEBRAL BODIES AND SPINAL CORD

For easy dissection, the sympathetic chain is identified and released with disconnection of the rami communicantes. The remnants of the intercostal muscles lying between the resected ribs are dissected off the segmental vessels (Fig. 26-21). If necessary, the intercostal vessels may be ligated and transected anterior to the vertebral body, but the segmental nerves should be preserved. After retraction of the parietal pleura from the anterior side of the vertebrae, flexible spatulas may be inserted so that two to three vertebrae are laterally visualized from behind (Fig. 26-22).