Pollution in theatre and scavenging

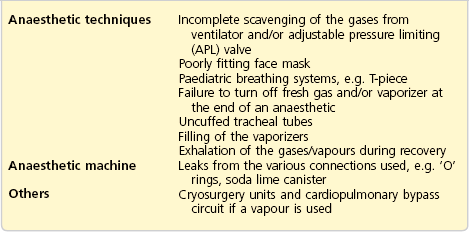

Since the late 1960s, there has been speculation that trace anaesthetic gases/vapours may have a harmful effect on operating theatre personnel. It has been concluded from currently available studies that there is no association between occupational exposure to trace levels of waste anaesthetic vapours in scavenged operating theatres and adverse health effects. However, it is desirable to vent out the exhaled anaesthetic vapours and maintain a vapour-free theatre environment. A prudent plan for minimizing exposure includes maintenance of equipment, training of personnel and routine exposure monitoring. Although not universally agreed upon, the recommended maximum accepted concentrations in the UK (issued in 1996), over an 8-hour, time-weighted average (see Table 3.1 for main causes), are as follows:

Methods used to decrease theatre pollution are listed below:

1. Adequate theatre ventilation and air conditioning, with frequent and rapid changing of the circulating air (15–20 times per hour). This is one of the most important factors in reducing pollution. Theatres that are unventilated are four times as contaminated with anaesthetic gases and vapours compared to those with proper ventilation. A non-recirculating ventilation system is usually used. A recirculating ventilation system is not recommended. In labour wards, where anaesthetic agents including Entonox are used, rooms should be well ventilated with a minimum of five air changes per hour.

2. Use of the circle breathing system. This system recycles the exhaled anaesthetic vapours, absorbing CO2. It requires a very low fresh gas flow, so reducing the amount of inhalational agents used. This decreases the level of theatre environment contamination.

3. Total intravenous anaesthesia.

5. Avoiding spillage and using fume cupboards during vaporizer filling. This used to be a significant contributor to the hazard of pollution in the operating theatre. Modern vaporizers use special agent-specific filling devices as a safety feature and to reduce spillage and pollution.

Scavenging

The performance of the scavenging system should be part of the anaesthetic machine check.

Scavenging systems can be divided into passive and active systems.

Passive system

The passive system is simple to construct with zero running cost.

Components

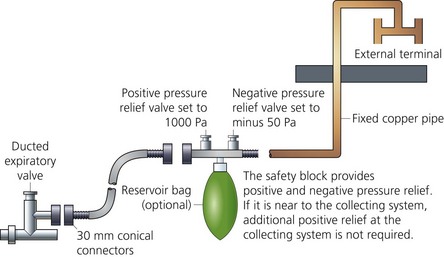

1. The collecting and transfer system which consists of a shroud connected to the adjustable pressure limiting (APL) valve (or expiratory valve of the ventilator). A 30-mm connector attached to transfer tubing leads to a receiving system (Fig. 3.1). The 30-mm wide-bore connector is designed as a safety measure in order to prevent accidental misconnection to other ports of the breathing system (Fig. 3.2).

2. A receiving system (reservoir bag) can be used. Two spring-loaded valves guard against excessive positive pressures (1000 Pa) in case of a distal obstruction or negative pressures (−50 Pa) in case of increased demand in the scavenging system. Without these valves, excessive positive pressure increases the risk of barotrauma should there be an obstruction beyond the receiving system. Excessive negative pressure could lead to the collapse of the reservoir bag of the breathing system and the risk of rebreathing.

3. The disposal system is a wide-bore copper pipe leading to the atmosphere directly or via the theatre ventilation system.

Problems in practice and safety features

1. Connecting the scavenging system to the exit grille of the theatre ventilation is possible. Recirculation or reversing of the flow is a problem in this situation.

2. Excess positive or negative pressures caused by the wind at the outlet might affect the performance and even reverse the flow.

3. The outlet should be fitted with a wire mesh to protect against insects.

4. Compressing or occluding the passive hose may lead to the escape of gases/vapours into the operating theatre so polluting it. The disposal hose should be made of non-compressible materials and not placed on the floor.

Active system

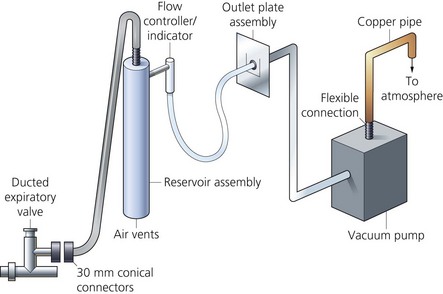

1. The collecting and transfer system which is similar to that of the passive system (Fig. 3.3).

2. The receiving system (Fig 3.4) is usually a valveless, open-ended reservoir positioned between the receiving and disposal components. A bacterial filter situated downstream and a visual flow indicator positioned between the receiving and disposal systems can be used. A reservoir bag with two spring-loaded safety valves can also be used as a receiving system.

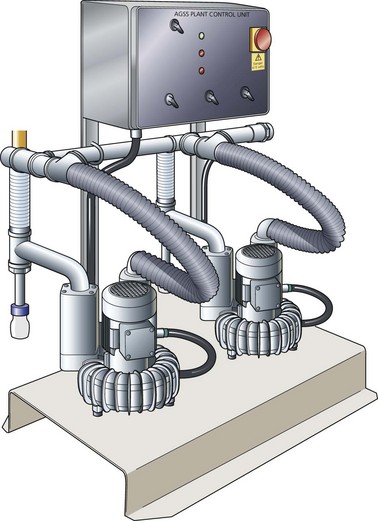

3. The active disposal system consists of a fan or a pump used to generate a vacuum (Fig. 3.5).

Mechanism of action

1. The vacuum drives the gases through the system. Active scavenging systems are able to deal with a wide range of expiratory flow rates (30–130 L/min).

2. A motorized fan, a pump or a Venturi system is used to generate the vacuum or negative pressure that is transmitted through the pipes.

3. The receiving system is capable of coping with changes in gas flow rates. Increased demands (or excessive negative pressure) allow ambient air to be entrained so maintaining the pressure. The opposite occurs during excessive positive pressure. As a result, a uniform gas flow is passed to the disposal system.

Problems in practice and safety features

1. The reservoir is designed to prevent excessive negative or positive pressures being applied to the patient. Excessive negative pressure leads to the collapse of the reservoir bag of the breathing system and the risk of rebreathing. Excessive positive pressure increases the risk of barotrauma should there be an obstruction beyond the receiving system.

2. An independent vacuum pump should be used for scavenging purposes.

Charcoal canisters (Cardiff Aldasorber)

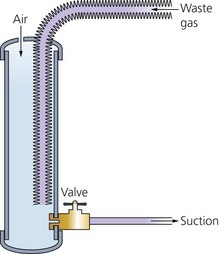

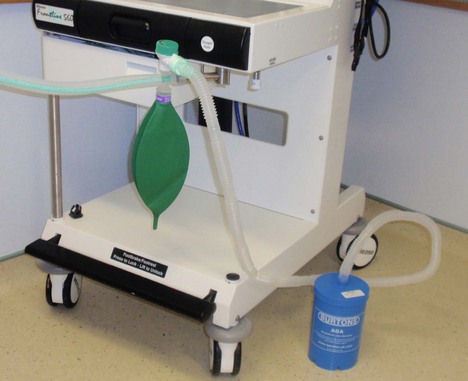

The canister is a compact passive scavenging system (Fig. 3.6).

American Institute of Architects. Guidelines for construction and equipment of hospitals and medical facilities. Washington DC: AIA; 1992.

Department of Health. Advice on the implementation of the Health and Safety Commission’s occupational exposure standards for anaesthetic agents. London: DoH; 1996.

Health Service Advisory Committee. Anaesthetic agents: controlling exposure under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations (COSHH). London: HSAC; 1996.

Henderson K.A., Raj A., Hall J.E. The use of nitrous oxide in anaesthetic practice: a questionnaire survey. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(12):1155–1158.

MHRA. Medical device alert: anaesthetic gas scavenging systems (AGSS) – all manufacturers (MDA/2010/021). Online. Available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Safetywarnings/MedicalDeviceAlerts/CON076104, 2010.

United States Department of Labor. Anaesthetic gases: guidelines for workplace exposures. Online. Available at http://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/anestheticgases/index.html, 1999.

In the following lists, which of the statements (a) to (e) are true?

a) The Cardiff Aldasorber can absorb N2O and the inhalational agents.

b) The circulating air in theatre should be changed 15–20 times per hour.

c) In the scavenging system, excessive positive and negative pressures should be prevented from being applied to the patient.

d) In the active scavenging system, an ordinary vacuum pump can be utilized.

e) The maximum accepted concentration of nitrous oxide is 100 ppm.

2. Important factors in reducing pollution in the operating theatre:

b) Low-flow anaesthesia using the circle system.

c) Adequate theatre ventilation.

a) Is easy to build and maintain.

c) There is no need to have positive or negative relief valves in the collecting system.

d) The exhaled gases are driven by the patient’s respiratory effort or the ventilator.

4. Concerning anaesthetic agents pollution:

a) There is an international standard for the concentrations of trace inhalational agents in the operating theatre environment.

b) In the UK, monitoring of inhalational agent concentration in the operating theatre is done annually.

c) PPM stands for particles per million.

d) An unscavenged operating theatre would have less than 100 particles per million of nitrous oxide.

e) A T-piece paediatric breathing system can cause theatre pollution.

a) False. Cardiff Aldasorber can only absorb the inhalational agents but not nitrous oxide. This limits its use in reducing pollution in the operating theatre.

b) True. Changing the circulating air in the operating theatre 15–20 times per hour is one of the most effective methods of reducing pollution. An unventilated theatre is about four times more polluted compared to a properly ventilated one.

c) True. The patient should be protected against excessive positive and negative pressures being applied by the scavenging system. Excessive positive pressure puts the patient under the risk of barotrauma. Excessive negative pressure causes the reservoir in the breathing system to collapse thus leading to incorrect performance of the breathing system.

d) False. Because of the nature of the flow of the exhaled gases, the scavenging system should be capable of tolerating high and variable gas flows. The flow of exhaled gases is very variable during both spontaneous and controlled ventilation. An ordinary vacuum pump might not be capable of coping with such variable flows, from 30 to 120 L/min. The active scavenging system is a high-flow, low-pressure system. A pressure of −0.5 cm H2O to the patient breathing system is needed. This cannot be achieved with an ordinary vacuum pump (low-flow, high-pressure system).

e) True. In the UK, the maximum accepted concentration of nitrous oxide is 100 ppm over an 8-hour time-weighted average.

2. Important factors in reducing pollution in the operating theatre:

a) True. In any location in which inhalation anaesthetics are administered, there should be an adequate and reliable system for scavenging waste anaesthetic gases. Unscavenged operating theatres can show 400–3000 ppm of N2O, which is much higher than the maximum acceptable concentration.

c) True. One of the most important factors in reducing pollution is adequate theatre ventilation. The circulating air is changed 15–20 times per hour. Unventilated theatres are four times more contaminated than properly ventilated theatres.

d) False. Modern vaporizers use agent-specific filling keys which limit spillage.

e) False. Cardiff Aldasorber absorbs the inhalational agents but not nitrous oxide.

a) True. A passive scavenging system is easy and cheap to build and costs nothing to maintain. There is no need for a purpose-built vacuum pump system with the necessary maintenance required.

b) False. The passive system is not an efficient system. Its efficiency depends on the direction of the wind blowing at the outlet. Negative or positive pressure might affect the performance and even reverse the flow.

c) False. The positive pressure relief valve protects the patient against excessive pressure build up in the breathing system and barotrauma. The negative pressure relief valve prevents the breathing system reservoir from being exhausted, ensuring correct performance of the breathing system.

d) True. The driving forces for gases in the passive system are the patient’s respiratory effort or the ventilator. For this reason, the transfer tubing should be made as short as possible to reduce resistance to flow.

e) False. 30-mm connectors are used in the UK as a safety feature to prevent misconnection.

4. Concerning anaesthetic agents pollution:

a) False. There is not an international standard for the concentrations of trace inhalational agents in the operating theatre environment. This is mainly because of unavailability of adequate data. Different countries set their own standards but there is an agreement on the importance of maintaining a vapour-free environment in the operating theatre.

b) True. Monitoring of inhalational agent concentration in the operating theatre is done annually in the UK and on a quarterly basis in the USA in each location where anaesthesia is administered.

c) False. PPM (capitals) stands for planned preventative maintenance, whereas ppm (small letters) stands for particles per million.

d) False. An unscavenged operating theatre would have 400–3000 ppm of nitrous oxide. In the UK, the recommended maximum accepted concentration over an 8-hour time-weighted average is 100 ppm of nitrous oxide.

e) True. A T-piece paediatric breathing system can cause theatre pollution because of the open-ended reservoir. A modified version has an APL valve allowing scavenging of the anaesthetic vapours (see Chapter 4).