CHAPTER 4 Physical Examination of the Elbow

HISTORY

Functionally, the elbow is the most important joint of the upper extremity, because it places the hand in space away from or toward the body. It provides the linkage, allowing the hand to be brought to the torso, head, or mouth. Because of this, the examiner must be aware of the interplay of shoulder and wrist function as they complement the usefulness of the elbow. However, a considerable limitation of elevation and abduction function can exist at the shoulder complex without producing an appreciable compromise in most activities of daily living. This is true because only a relatively small amount of shoulder flexion and rotation is necessary to place the hand about the head or posteriorly about the waist or hip, and scapulothoracic motion can compensate for glenohumeral motion loss. Full pronation and supination can be achieved only when both the proximal and distal radioulnar joints are normal.6,25

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

AXIAL ALIGNMENT

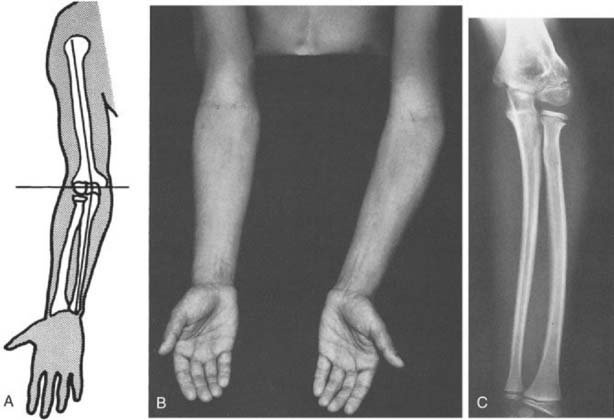

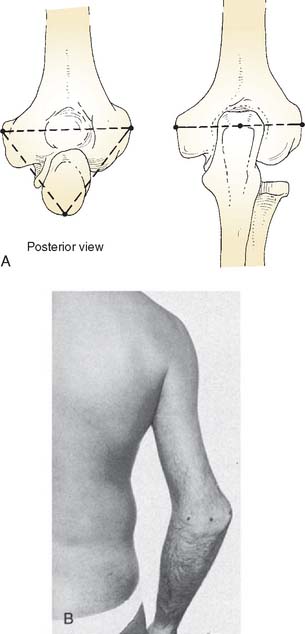

Axial malalignment of the elbow, when compared with the opposite side, suggests prior trauma or a skeletal growth disturbance. To determine the carrying angle, the forearm and hand should be supinated and the elbow extended; the angle formed by the humerus and forearm is then determined (Fig. 4-1A). Although there is considerable variation with race, age, sex, and body weight, an average of 10 degrees for men and 13 degrees for women has been calculated as the mean carrying angle from several reports.3,4,13,14

Angular deformities, such as cubitus varus or valgus, are also easily identifiable (see Fig. 4-1B and C). The elbow moves from a valgus to varus alignment as with flexion. In a post-traumatic condition, however, abnormalities in the carrying angle cannot be accurately assessed in the presence of a significant flexion contracture (see Chapter 3). Rotational deformities following supracondylar or other fractures of the humeral shaft may be difficult to perceive.

LATERAL ASPECT

Fullness about the infracondylar recess just inferior to the lateral condyle of the humerus, the “soft spot,” suggests either an increase in synovial fluid, synovial tissue proliferation, or radial head pathology, such as fracture, subluxation, or dislocation (Fig. 4-2). Subtle evidence of effusion can be determined by observing fullness in this area.

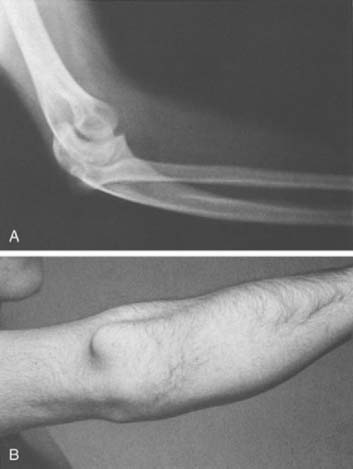

Thin, taut, adherent skin over the lateral epicondyle may be indicative of excessive cortisone injections in this area for refractory lateral epicondylitis (see Chapter 44). A prominence involving the lateral triangle often indicates a posteriorly dislocated radial head (Fig. 4-3; see Fig. 4-22A and B).

POSTERIOR ASPECT

A prominent olecranon suggests a posterior subluxation or migration of the forearm on the ulnohumeral articulation. Occasionally, marked distortion is associated with surprisingly satisfactory function (Fig. 4-4). Rupture of the triceps tendon at its insertion should be suspected if this finding is accompanied by loss of active extension. Loss of terminal passive extension of the elbow is a sensitive but nonspecific indicator of intra-articular pathology. Loss of active motion with full passive extension suggests either mechanical (triceps avulsion) or neurologic conditions.

The prominent subcutaneous olecranon bursa is readily observed posteriorly when it is inflamed or distended (Fig. 4-5). Rheumatoid nodules frequently are found on the subcutaneous border of the ulna (see Chapter 74).

MEDIAL ASPECT

On occasion the ulnar nerve may be observed to displace anteriorly during flexion with recurrent subluxation of the ulnar nerve.8 Otherwise, few landmarks are observable from the medial aspect of the joint. The prominent medial epicondyle is evident unless the patient is obese.

ASSOCIATED JOINTS AND NEURAL FUNCTION

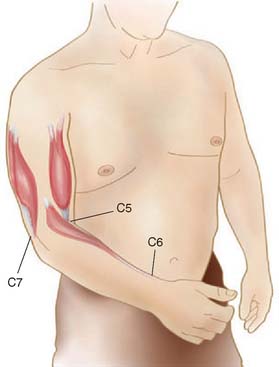

No examination of the elbow is complete without a review of the cervical spine and all other components of the upper extremity. If the elbow pain has a radicular pattern, it is important to review the patient’s cervical spine alignment and range of motion and perform neurologic testing of the entire upper extremity. The main nerve roots involved with elbow function are C5-7 (Fig. 4-6). There is considerable overlap in the sensory dermatomes of the upper extremity. The general distribution of sensory levels includes C5, the lateral arm; C6, the lateral forearm; C7, the middle finger; and C8 and T1, the medial forearm and arm dermatomes, respectively.

Biceps function from innervation of C5-C6 is a flexor of the elbow and forearm supinator. The reflex primarily tests C5 and some C6 competency. The C6 muscle group of most interest is the mobile wad of three, consisting of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis and the brachioradialis muscles. These also are known as the radial wrist extensors and should be assessed for strength and reflex integrity. The reflex is primarily a C6 function, with some C5 component. The primary elbow muscle innervated by C7 is the triceps, which should always be assessed for strength and reflex. Wrist flexion and finger extension also are primarily supplied by C7, with some C8 innervation (see Fig. 4-6).

For normal forearm rotation, there must be a normal anatomic relationship between the proximal and distal radioulnar joint. Inflammatory changes involving either the elbow or the wrist or both will cause a loss of forearm rotation. Disruption of the normal relationship of the distal radioulnar joint will cause dorsal prominence of the distal ulna exaggerated by pronation and is lessened by supination. Because pronation is the common resting position of the hand, dorsal subluxation of the ulna at the wrist is often identifiable by inspection.

PALPATION

OSSEOUS LANDMARKS

Inspection and palpation of the medial and lateral epicondyles and the tip of the olecranon form an equilateral triangle when the elbow is flexed (Fig. 4-7). Fracture, malunion, unreduced dislocation, or growth disturbances involving the distal end of the humerus can be assessed clinically in this fashion.

LATERAL ASPECT

The lateral supracondylar region, which we call the lateral column, is readily palpable and is a valuable landmark during lateral surgical exposures (Fig. 4-8) (see Chapters 7 and 32). The definition of the location of the extensor carpi radialis brevis is carefully sought and is enhanced by radial wrist and elbow extension. Examination of the radial head is easily performed provided a joint effusion is not present. Digital pressure over the peripheral articular surface of the radial head, when combined with pronation and supination of the forearm in varying degrees of elbow flexion, will offer valuable information about this bony structure and the status of the synovium. If painful, this examination should be performed gently. Radial head or capitellar fracture thus may be suspected even when the radiographic results are negative. An effusion of the elbow is most easily identified by palpation over the lateral borderof the radial head or about the posterior recess located just between the radial head and the lateral border of the olecranon (Fig. 4-9). A radio/humeral plica is appreciated by palpating the snapping of the plica with flexion and extension. As with other joints, significant effusions of hemarthrosis will limit extremes of motion, especially extension. If tense, the elbow will assume a position of maximum joint capacity, which is 80 degrees.19 Palpation of the arcade of Froshe, located approximately 2 cm anterior and 3 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle, locates the posterior interosseous nerve.

MEDIAL ASPECT

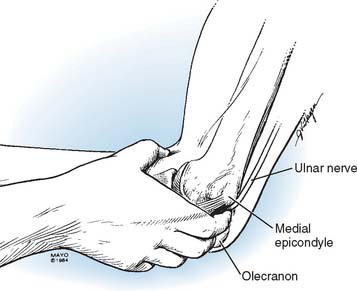

Because of the tight ligament and capsule present on the medial side of the olecranon, great difficulty is encountered in assessment of the soft tissues in this area. Palpation of the cubital tunnel is easily performed to assessthe status of the ulnar nerve (Fig. 4-10). A subluxing nerve is identified with flexion and extension. Entrapment is assessed by performing a Tinel test proximal to, at, or distal to the cubital tunnel.

FIGURE 4-10 Palpation of the cubital tunnel. The ulnar nerve is identified proximal and distal to the medial epicondyle.

The medial collateral ligament is the elbow’s primary stabilizer to valgus strain. It takes its origin slightly anterior and inferior to the medial epicondyle and fans out to attach along the greater sigmoid fossa of the ulna with both an anterior and a posterior thickening.24 With the elbow in 30 to 60 degrees of flexion, it should be palpated for tenderness along its course. Valgus stress is painful if the ligament is injured.

POSTERIOR ASPECT

The olecranon bursa overlies the triceps aponeurosis, which inserts on the olecranon. This area should be palpated for thickening and pain. On occasion, a spur or bony prominence may be readily palpable at the tip of the olecranon (see Chapter 84).

ANTERIOR ASPECT

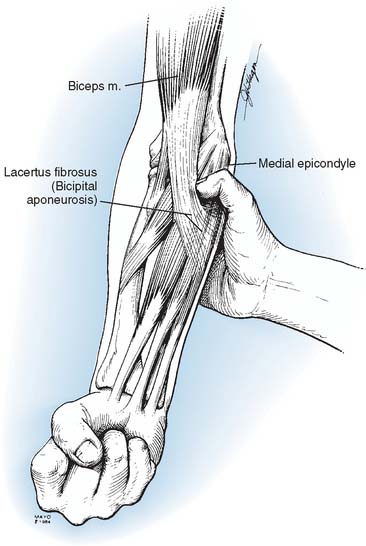

The musculocutaneous nerve supplying lateral forearm sensation is located deep to the brachioradialis between it and the biceps tendon and is not readily palpable. The biceps tendon is readily palpable with resisted forearm supination. The tendon should be assessed for tenderness and for continuity distally. A medial expansion, the lacertus fibrosus, is noted, which covers the common flexor muscle group as well as the brachial artery and median nerve and may be the source of compression of the median nerve. The pulse of the brachial artery is easily located, lying deep to the lacertus fibrosus (Fig. 4-11).

MOTION

Perhaps no portion of the physical examination is more important than the assessment of motion. Loss of full extension is the first motion altered by most pathology. As a matter of fact, in a trauma situation, the likelihood of significant joint pathology in the face of normal elbow motion is so small as not to require radiographic analysis!15

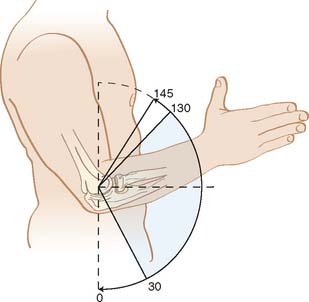

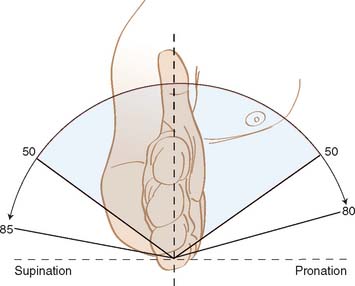

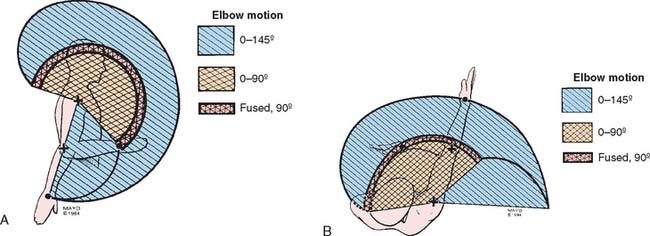

Normally, the arc of flexion-extension, although variable, ranges from about 0 to 140 degrees plus or minus 10 degrees (Fig. 4-12).1,7,26 This range exceeds that which is normally required for activities of daily living.17 Pronation-supination may vary to a greater extent than the arc of flexion-extension. Acceptable norms ofpronation and supination are 75 and 85 degrees, respectively (Fig. 4-13). In assessing motion, the examiner should record both active and passive values. The humerus is placed in a vertical position when evaluating the arc of forearm rotation. Patients will tend to accommodate for loss of pronation by abducting the shoulder. Any significant difference between active and passive ranges of motion suggests pain or motor function as the cause. In patients with a flexion or extension contracture, the examiner should concentrate on solid or soft end points, pain or crepitus during the arc and at the end points.

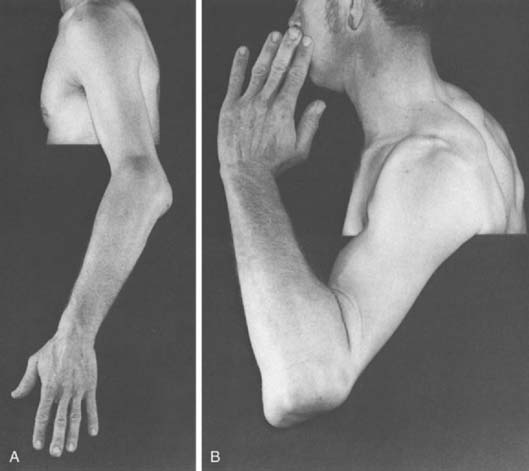

The examiner should then make a careful assessment of any compromised motion at the shoulder or wrist. Often, the disability will arise from a combination of factors, but it should be stressed that a full range of motion at the elbow is not essential for performance of the activities of daily living. The essential arc of elbow flexion-extension required for daily activities ranges from about 30 to 130 degrees.17 Because the loss of extension up to a certain degree only shortens the lever arm of the upper extremity, flexion contractures of less than 45 degrees may have little practical significance, although patients sometimes are concerned about the cosmetic appearance (Fig. 4-14).

To perform 90% of required daily activity, 50 degrees of pronation and supination are required (see Fig. 4-13).17 For most individuals, pronation is the most important function on the dominant side for eating and writing, and loss of pronation is compensated by shoulder abduction. On the other hand, a loss of supination of the nondominant side may significantly hinder personal hygiene needs, accepting objects, and opening of door handles. These tasks are poorly compensated by shoulder or wrist function.

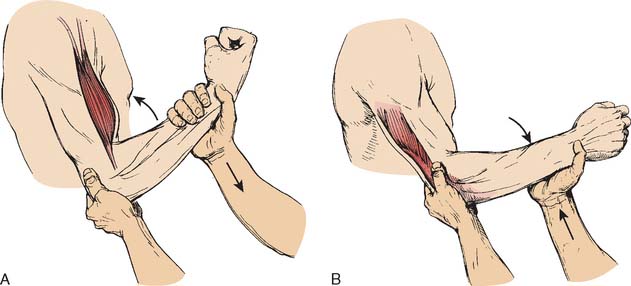

STRENGTH

Only gross estimates of strength are attainable in the clinical setting. Flexion and extension strength testing (Fig. 4-15) is conducted against resistance, with the forearm in neutral rotation and the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion. Extension strength is normally 70% that of flexion strength2 and is best measured with the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion, and with the forearm in neutral rotation.10,22,23,27 Pronation (Fig. 4-16), supination, and grip strength are also best studied with the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion and the forearm in neutral rotation. Supination strength is normally about 15% greater than pronation strength.2 The dominant extremity is about 5% to 10% stronger than the nondominant side, and women are 50% as strong as men (see Chapter 5).2

INSTABILITY

In the absence of articular cartilage loss, the mechanical integrity of the radial and ulnar collateral ligaments is difficult to assess because of the intrinsic stability offered by the closely approximated surfaces of the olecranon and trochlea and the buttressing effect of the radial head against the capitellum. However, when articular cartilage has been destroyed, as in rheumatoid arthritis, or removed, as with radial head excision, collateral ligament stability can be determined by the application of varus and valgus stresses. Medially, the fibers become taut in an ordered sequential fashion, proceeding from anterior to posterior as the elbow is flexed.22 Accordingly, a portion of the complex is always in tension throughout the arc of flexion (see Chapter 3).24

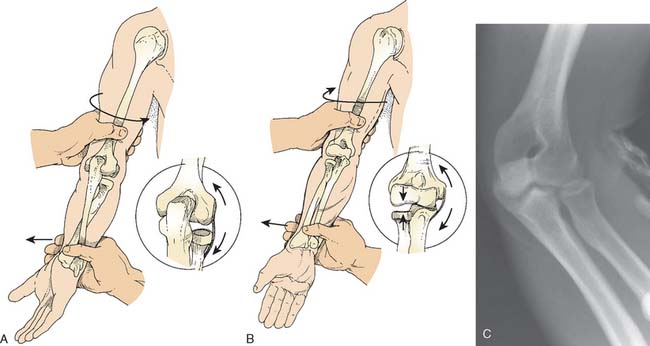

The radial collateral ligament resists varus stress throughout the arc of elbow flexion with varying contributions of the anterior capsule and articular surface in extension (see Chapter 3). The lateral collateral ligament complex consists of the radial collateral ligament (RCL) and the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL). The RCL maintains consistent patterns of tension throughout the arc of flexion.24 To properly assess collateral ligament integrity, the elbow should be flexed to about 15 degrees. This relaxes the anterior capsule and removes the olecranon from the fossa. Varus stress is best applied with the humerus in full internal rotation. Valgus instability is best measured with the arm in 10 degrees of flexion (Fig. 4-17). In recent years, we have used the fluoroscan routinely to assess all elbows in where a possible instability exists (see Fig. 4-17C).

ROTATORY INSTABILITY

The lateral collateral complex also includes a narrow but stout band of ligamentous tissue blending with the distal and posterior fibers of the capsule to insert distally on the crista supinatoris of the ulna. This is the lateral ulnar collateral ligament.20,24

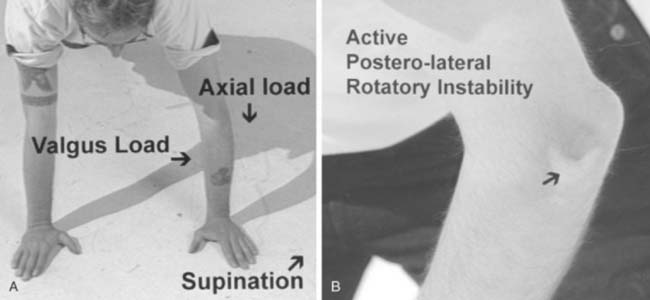

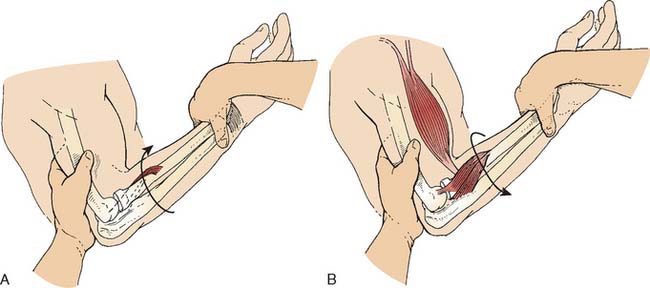

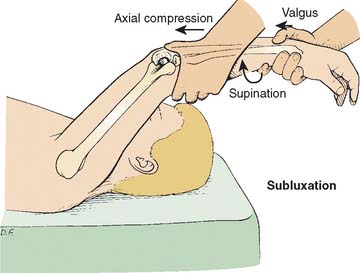

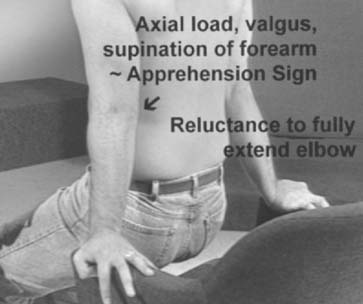

Insufficiency of the lateral collateral ligament is responsible for posterolateral instability of the elbow.20 Posterolateral instability is elicited in two ways (see Chapter 44). The more sensitive is by flexing the shoulder and elbow 90 degrees, with the patient supine. The patient’s forearm is fully supinated, and the examiner grasps the wrist or forearm and slowly extends the elbow while applying valgus and supination movements and an axial compressive force (Fig. 4-18). This produces a rotatory subluxation of the ulnohumeral joint; that is, the rotation dislocates the radiohumeral joint posterolaterally by a coupled motion. As the elbow approaches extension, a posterior prominence (the dislocated radiohumeral joint) is noted with an obvious dimple in the skin proximal to the radial head (Fig. 4-19). Additional flexion results in a sudden reduction as radius and ulna visibly snap into place on the humerus (Fig. 4-20). Alternatively, simply asking the patient to rise from a chair may also reproduce the symptomatology (Fig. 4-21). Finally, having the patient do a push-up places the elbow in the at-risk position (Fig. 4-22). These latter two tests are active apprehension signs.

1 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Joint Motion: Method of measuring and recording. Chicago: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1965.

2 Askew L.J., An K.N., Morrey B.F., Chao E.Y. Functional evaluation of the elbow: normal motion requirements and strength determination. Orthop. Trans. 1981;5:304.

3 Atkinson W.B., Elftman H. The carrying angle of the human arm as a secondary symptom character. Anat. Rec. 1945;91:49.

4 Beals R.K. The normal carrying angle of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1976;119:194.

5 Beetham W.P.Jr., Polley H.F., Slocumb C.H., Weaver W.F. Physical Examination of the Joints. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1965.

6 Bert J.M., Linscheid R.L., McElfresh E.C. Rotatory contracture of the forearm. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1163.

7 Boone D.C., Azen S.P. Normal range of motion of joints in male subjects. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:756.

8 Childress H.M. Recurrent ulnar nerve dislocation at the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1975;108:168.

9 Daniels L., Williams M., Worthingham C. Muscle Testing: Techniques of Manual Examination, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1946.

10 Elkins E.C., Ursula M.L., Khalil G.W. Objective recording of the strength of normal muscles. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1951;33:639.

11 Hoppenfeld S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1976.

12 Johansson O. Capsular and ligament injuries of the elbow joint. Acta Chir. Scand. Suppl. 1962;287:1.

13 Keats T.E., Teeslink R., Diamond A.E., Williams J.H. Normal axial relationships of the major joints. Radiology. 1966;87:904.

14 Lanz T., Wachsmuth W. Praktische Anatomie. Berlin: ARM, Springer-Verlag, 1959.

15 Lennon R.I., Riyat M.S., Hilliam R., Anathkrishnan G., Alderson G. Can a normal range of elbow movement predict a normal elbow x-ray? Emerg Med J. 2007;24:86.

16 McRae R. Clinical Orthopedic Examination. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1976.

17 Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., An K.N., Chao E.Y. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:872.

18 Morrey B.F., Chao E.Y. Passive motion of the elbow joint. A biomechanical study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:63.

19 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Intra-articular pressuring capacity of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:100.

20 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Intra-articular pressuring capacity of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:440.

21 O’Neill O.R., Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.N. Compensatory motion in the upper extremity after elbow arthrodesis. Clin. Orthop. 1992;281:89.

22 Provins K.A., Salter N. Maximum torque exerted about the elbow joint. J. Appl. Physiol. 1955;7:393.

23 Rasch P.J. Effect of position of forearm on strength of elbow flexion. Res. Q. 1955;27:333.

24 Regan W.D., Korinek S.L., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Biomechanical study of ligaments about the elbow joint. Clin. Orthop. 1991;271:170.

25 Schemitsch E.H., Richards R.R., Kellam J.F. Plate fixation of fractures of both bones of the forearm. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:345.

26 Wagner C. Determination of the rotary flexibility of the elbow joint. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1977;37:47.

27 Williams M., Stutzman L. Strength variation through the range of motion. Phys. Ther. Rev. 1959;39:145.

28 Youm Y., Dryer R.F., Thambyrajahk K., Flatt A.E., Sprague B.L. Biomechanical analysis of forearm pronation-supination and elbow flexion-extension. J. Biomech. 1979;12:245.