CHAPTER 2 Phases of the surgical procedure

Preparation of the patient

There are two quite different aspects of this preparation: (i) physical, and (ii) mental/emotional.

Physical

Aspects of the patient’s health, including use of medications that will impact the surgical episode, must be known by the operating surgeon. In order to assure that these are understood and that information is not overlooked, detailed written procedure forms are advisable. For example, asking patients if they are taking aspirin may result in false negatives simply because patients are unaware that one of their medications contains aspirin. Therefore, they need to be asked, ‘Are you taking any of the following medications?’ and then be provided with a list of medications that contain aspirin (Appendix 1). These queries are often best understood and answered when written, so the patient can gather needed information and assemble necessary medical records.

Detailed instructions about what is needed prior to the surgery should be provided, including suggested changes in medications, with clearly stated dates and times when such changes are to be made (Appendix 2). Insurance considerations are often complex and must be addressed.

It is essential that postoperative plans be made and understood preoperatively: time and place for follow-up visits, contact information, likely postoperative medications and limitations on activity (Appendix 3). Also, it is important for the patient and the operating surgeon to know who will be in charge of the postoperative care. Ideally, this should be the operating surgeon. When this is not possible, the patient must know that fact preoperatively and be agreeable to the suggested plans.

Mental/emotional aspects

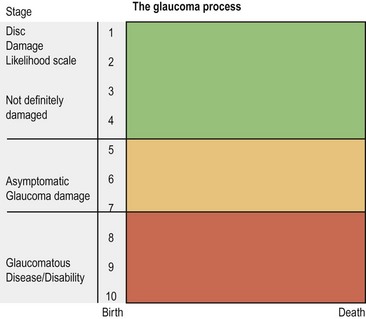

Blindness is not only incapacitating but is also disabling to the spirit. The thought of eye surgery is thus deeply threatening for most individuals. It is the ophthalmologist’s duty, therefore, to explain tactfully to patients the nature of their problem and to mention the available options for managing it. Such a discussion should include the possibility of treatment by non-surgical means, the nature of surgical options (with attention toward reasonable prognosis), the effect the surgery would probably have on the patient’s life style, the probability of partial or total disability, and the anticipated costs. They should also include a discussion of what is likely to happen in the absence of surgery. If the surgeon cannot in good faith and to a high degree of certainty provide such information, surgery is not justified. Figure 2.1 provides a graphic representation of this idea, a concept which is important both to the patient and to the surgeon.

A variety of forms can be utilized to help provide the patient with the necessary information regarding his diagnosis, hospitalization, and recovery (Appendix 3). While brochures prepared by professional firms and various agencies are available, it is a relatively simple thing for surgeons to prepare such forms themselves. The forms are then more likely to be fully pertinent. Such information, however, should never be considered a substitute for direct communication between the patient and the surgeon. While patients do, to varying degrees, want to know technical and practical details, what they must know without doubt is that they trust their surgeon. That trust is the consequence of the patient having an unwavering belief that the surgeon unquestionably intends to be of benefit to the patient. The patient knows that if such sincere intent is present, the surgeon will require himself or herself to act competently. When the provision of brochures, or discussions with paramedical personnel, lead the patients to feel that those brochures or discussions are primarily to save the surgeon time and to avoid personal responsibility, they actually decrease the patient’s trust.

Informed consent or informed choice

‘Informed consent’ involves important medical and ethical considerations as well as the more strictly legal ones1. The following discussion will deal primarily with the ethical aspects of informed consent, with the meaning of the phrase, and with its importance for the patient, the physician, and the medical profession2,3,4.

Informed consent is not merely the obtaining of a signature on a piece of paper. In fact, the act of having a patient sign a written consent for surgery unfortunately sometimes serves as a means to avoid obtaining truly informed consent5.

Some physicians appear to believe that the major purpose for obtaining a signed ‘informed consent’ is to prevent malpractice suits. The extreme mental and emotional stress that often accompanies such lawsuits makes prevention of them a deservedly important goal. However, simply because a patient signs a form stating that he or she gives permission for a particular operation does not eliminate the chance that the patient will institute litigation6–10. Patients may state at a later date that they did not really understand the form. Misunderstandings cannot be avoided. Some individuals hear only what they want to hear. In fact, it has been shown that patients forget more than they recall the information given to them preoperatively11–13. A properly executed informed consent may provide protection for the surgeon or institution at a later date. However, an informed consent form in itself will not effectively prevent malpractice suits from being filed14,15.

On the other hand, the process of obtaining true informed consent – that is, the meaningful interchange of information, anticipations, hopes, and fears that should precede a request for the patient to sign any form – does help limit the likelihood that suit will be brought at a later date6–10. It must be remembered that the form is only documentation of the discussion; the form is not the consent.

Failure to obtain adequate informed consent is not the basis for many malpractice claims, usually less than 2%16–18. Most plaintiffs’ lawyers plead lack of informed consent as a last-resort allegation in weak cases, and do not as a rule use it as a primary charge against a negligent doctor.

The overwhelming reason lawsuits are brought against physicians is because the patients have unfulfilled expectations6–10. Wise surgeons do not minimize risks or maximize benefits; wise surgeons make sure that patients’ expectations are realistic, being neither inappropriately bleak nor bright. Many forms of information, including electronic, are now available. They may provide highly valuable educational material, but patients may be misled and may come to expect unreasonable outcomes.

Paradoxically, there are risks to the patient in obtaining informed consent. The individual who stands to be helped by cataract extraction, for example, may decline surgery when he hears his surgeon say, ‘You may lose your eye.’ Information itself changes people’s moods and feelings. The suggestible patients who are fully informed of the difficulties that occasionally plague persons with otherwise successful surgery, such as a ‘dry eye’ following lid procedures or glare following cataract extractions may effectively, convince themselves that they cannot be rehabilitated. Were such individuals less completely apprised of the possible risks, they might have managed quite satisfactorily. Furthermore, though the situations rarely occur, some patients who are functioning well can become incapacitated when burdened with greater knowledge of their illness19,20. We must remember that both the manner of obtaining informed consent and the information itself can be damaging to the patient. Importantly, however, it is almost never the specific risks that dissuade patients from having surgery. Rather, it is the manner in which the discussions are held. Some physicians use the obtaining of an informed consent as a means to avoid being held accountable for the outcome – legally or ethically. Patients sense this and lose trust. Also, some surgeons use discussions of ‘informed consent’ in hopes that their patients will elect not to have the surgery, thus shifting the cause for any future worsening of the patient’s illness onto the patient. Unfortunately, this shoddy approach to patient care is not rare.

The effects on the physician, and consequently on the patient, of a litigative climate also factor strongly. The anxieties produced in the physician by this situation are certainly not conducive to good medical practice21–26. Having acknowledged this, however, it should quickly be added that surgical care should never be based solely on medicolegal considerations. Surgeons must in each case exercise their reasonable judgment based on their understanding of the case. This is not to say that the surgeon should be unaware of what is considered to be ‘standard practice’. The surgeon is in fact unlikely to be found negligent when practicing according to accepted standard. In a case in which the surgeon chooses to deviate from this standard, he should be aware that he is making such a deviation, be able to justify it, and indicate this to the patient. When standard care is not chosen, the proper concern is not whether litigation will ensue, but rather why such a deviation is in the patient’s best interest. The history of medicine makes it clear that standard levels of care are not always optimal levels of care. Conscientious physicians must constantly be evaluating the benefits and risks of the care they are offering. Often improvement in care will result only when deviations from that standard are made. Such alterations must be reasonable and in the best interests of the patient.

One of the prerequisites to obtaining informed consent is sufficient knowledge on the part of both doctor and patient (see Box 2.1). The physician must adequately understand the medical and surgical aspects of the case under consideration. He or she must also have a reasonable comprehension of the patient’s needs and wishes. Both the patient and the surgeon should compare the anticipated risks and benefits of not performing surgery. Not only must surgeons have an adequate knowledge of the medical aspects of the case, but also they must also be aware of their own motivations with regard to such questions as why they chose to perform or not to perform surgery. Surely the major intent of the surgeon is to make the patient better. However, the surgeon is subject to the full range of influences that affect human decisions, as well as physician-specific forces. Occasionally these may be of almost overwhelming weight. Included among these are: pressures from the patient or the patient’s family and friends, economic considerations, hope of acquiring new knowledge, curiosity regarding a new instrument or procedure, prestige associated with performing particularly difficult surgery, and the pleasure of conquering a difficult challenge. On the other hand there are considerations that may put pressure on the surgeon to avoid operating; these include concern that the surgery will damage the patient, timidity based on previous unfortunate experiences with similar surgery, worry that an unfavorable result will bring damaging litigation, unwillingness to perform a procedure with which the surgeon has not had extensive experience, and reluctance to refer the patient elsewhere because of economic or psychological reasons. To perform surgery is stressful and fatiguing. Where compensation for the performance of surgery is present, whether in the form of academic promotion, public acclaim or economic reward, the surgeon will be driven toward electing to do surgery. Conversely, where compensation is inadequate, or where the physician may be penalized for operating unsuccessfully, then the desire to perform surgery is greatly diminished27,28. The latter case is by no means necessarily preferable to the former. To deny a patient the possibility for improvement by means of surgery is just as unfortunate as to perform surgery when it is not likely to help. Patients have the best chance for receiving proper treatment when: (i) surgeons are adequately knowledgeable regarding both medical care and themselves, (ii) rewards and punishments are acceptable to both patients and physicians alike, (iii) and patients are knowledgeable enough to assess reasonably the quality of their care.

Box 2.1

Requirements for obtaining appropriate informed consent

One individual’s feelings about informed consent are expressed in the newspaper article in Box 2.2. Perhaps because it is an everyday part of the physician’s life, perhaps because the physician is unaware of what is occurring, or perhaps for other reasons, physicians are not always cognizant of the absolutely central role they play in patient care. Physicians and surgeons have not been replaced by computers, or CAT scanners, or surgical microscopes. These technological masterpieces can occasionally actually hamper the doctor–patient relationship.

Box 2.2

A commentary by a patient that provides insights into how many patients want their doctors to interact with them

The patient looks at his doctor

(Courtesy Intelligencer Journal/Lancaster New Era, Lancaster, PA.)

It may be helpful to consider obtaining an informed ‘choice’ rather than consent from the patient11. The word ‘choice’ emphasizes that the person making the decision is the patient, and not the doctor!

In summary, informed consent (or informed choice) is an essential part of medical practice, for five rather different reasons. First, it is the physician’s ethical responsibility to be honest with the patient29. Second, it is the patient’s right to make decisions regarding his or her destiny, and the patient is not in a position to do this without appropriate knowledge. Third, the process of obtaining informed consent is one of the most important practical ways of assuring high standards and improving quality of medical care. Fourth, the obtaining of an informed consent, or preferably informed choice, cements the doctor–patient relationship; it can reveal significant areas of misunderstanding or lack of trust. Dealing with these in a kind, caring and knowledgeable manner helps both the doctor and the patient understand each other better, leading to the firm bond that is essential to obtaining optimal care. Finally, the physician is legally obligated to obtain such consent30–33. It is important to remember that the basis of this legal requirement is society’s belief that the practice of obtaining an informed consent is societally necessary.

1 Faden RR, Beauchamp TL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986.

2 Spaeth GL. Informed choice, not informed consent. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992;23(10):648-649.

3 Jones JW, McCullough LB, Richman BW. Informed consent: it’s not just signing a form. Thorac Surg Clin. 2005;15(4):451-460.

4 Paterick TJ, Carson GV, Allen MC, et al. Medical informed consent: general considerations for physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):313-319.

5 Spaeth GL. Informed choice versus informed consent. Hektoen Internat. 2(2), 2010.

6 Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician–patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;227:553-559.

7 Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. The Lancet. 1994;343:1609-1613.

8 Danzon PM. The frequency and severity of medical malpractice claims: new evidence. Law Contemp Probl. 1986;49(2):58-84.

9 Leaman T, Saxton JW. Who will sue you next? Family Practice Management. September. 1996:36-40.

10 Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, et al. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1583-1587.

11 Priluck IA, Robertson DM, Buettner H. What patients recall of the preoperative discussion after retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87(5):620-623.

12 McDaniel Hutson M, Blaha JD. Patients recall of preoperative instruction for informed consent for an operation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1991;73(A):160-162.

13 Vallance JH, Ahmed M, Dhillon B. Cataract surgery and consent; recall, anxiety and attitude toward trainee surgeons preoperative and postoperatively. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(7):1479-1485.

14 Gatter R. Informed consent law and the forgotten duty of physician inquiry. Loyola Law J. 2000;31(4):557-597.

15 Bhattacharyya T, Yeon H, Harris MB. The medical-legal aspects of informed consent in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(11):2395-2400.

16 Cottam D, Lord J, Dallal RM, et al. Medicolegal analysis of 100 malpractice claims against bariatric surgeons. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(1):60-66. discussion 66–8

17 Rogers SOJr, Gawande AA, Kwaan M, et al. Analysis of surgical errors in closed malpractice claims at four liability insurers. Surgery. 2006;140(1):25-33.

18 Simonsen AR, Duncavage JA, Becker SS. A review of malpractice cases after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(9):977-979.

19 Hoffman J. Awash in information, patients face a lonely, uncertain road. The New York Times, 14 August 2005:A1.

20 Uzbeck M, Quinn C, Saleem I, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of standard and detailed risk disclosure prior to bronchoscopy on peri-procedure anxiety and satisfaction. Thorax. 2009;64(3):224-227.

21 Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525-533.

22 Kessler D, McClellan M. Do doctors practice defensive medicine? Quart J Econ. 1996;111(2):353-390.

23 Mello MM, Kelly CN. Effects of a professional liability crisis on residents’ practice decisions. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(6):1287-1295.

24 Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609-2617.

25 Doctors and other health professionals report that fear of malpractice has a big, and mostly negative, impact on medical practice, unnecessary defensive medicine and openness in discussing medical errors.’. Health Care News. 3(2), 2003. Harris Interactive, Inc

26 The Factors Fueling Rising Healthcare Costs. Prepared for America’s Health Insurance Plans, Price Waterhouse Cooper. America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2006.

27 Angell M. The doctor as double agent. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1993;3(3):279-286.

28 Fuchs VR. The ‘rationing’ of medical care. New Engl J Med. 1984;311(24):1572-1573.

29 . Principles of Medical Ethics American Medical Association. 17 June 2001. 22 July 2005 http://ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/212.html

30 Liang BA. Informed consent. In: Health Law and Policy: A Survival Guide to Medicolegal Issues for Practitioners. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2000:29-44.

31 Hanson LR. Informed consent and the scope of a physician’s duty to disclose. N D Law Rev. 2001;77(1):71-96.

32 Rosoff AJ. Consent to mental treatment. In: MacDonald MG, Kaufman RM, Capron AM, et al, editors. Treatise on Health Care Law. New York: Matthew Bender, 1991. p.17A.1–17A.7

33 Raab EL. The parameters of informed consent. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;102:225-232.