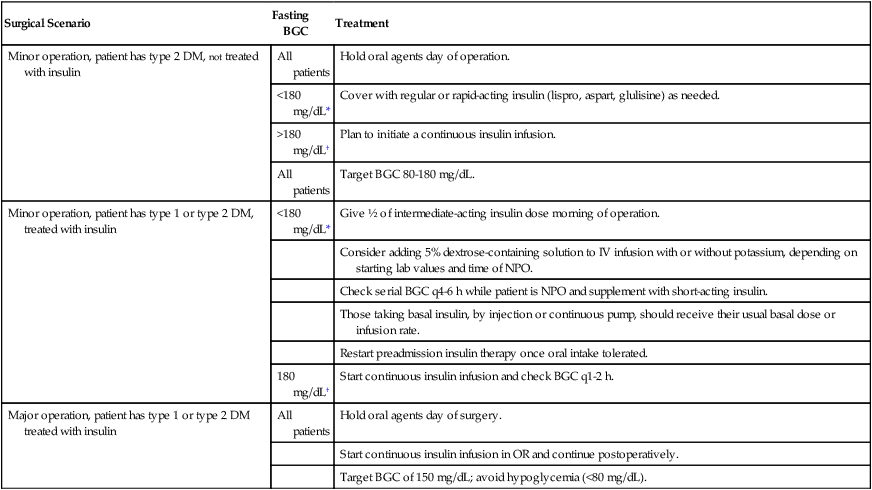

Perioperative management of blood glucose

The avoidance of hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, loss of electrolytes, and loss of free water and the prevention of ketogenesis are the main goals of perioperative glycemic control. To accomplish these goals, consideration should be paid to the type of diabetes mellitus (DM) the patient has, the antecedent pharmacologic therapy of the DM, the degree of metabolic control prior to surgery, and the type and duration of the operation the patient is to undergo. A summary of this approach is presented in Table 226-1.

Table 226-1

Perioperative Management of Patients with Diabetes Mellitus

| Surgical Scenario | Fasting BGC | Treatment |

| Minor operation, patient has type 2 DM, NOT treated with insulin | All patients | Hold oral agents day of operation. |

| <180 mg/dL* | Cover with regular or rapid-acting insulin (lispro, aspart, glulisine) as needed. | |

| >180 mg/dL† | Plan to initiate a continuous insulin infusion. | |

| All patients | Target BGC 80-180 mg/dL. | |

| Minor operation, patient has type 1 or type 2 DM, treated with insulin | <180 mg/dL* | Give ½ of intermediate-acting insulin dose morning of operation. |

| Consider adding 5% dextrose-containing solution to IV infusion with or without potassium, depending on starting lab values and time of NPO. | ||

| Check serial BGC q4-6 h while patient is NPO and supplement with short-acting insulin. | ||

| Those taking basal insulin, by injection or continuous pump, should receive their usual basal dose or infusion rate. | ||

| Restart preadmission insulin therapy once oral intake tolerated. | ||

| 180 mg/dL† | Start continuous insulin infusion and check BGC q1-2 h. | |

| Major operation, patient has type 1 or type 2 DM treated with insulin | All patients | Hold oral agents day of surgery. |

| Start continuous insulin infusion in OR and continue postoperatively. | ||

| Target BGC of 150 mg/dL; avoid hypoglycemia (<80 mg/dL). |

Adapted with permission from Smiley DD, Umpierrez GE. Perioperative glucose control in the diabetic or nondiabetic patient. South Med J. 2006;99:580-589.