Pemphigus

Management strategy

Other factors complicate the management, and include the following:

1. Circulating autoantibodies have a degradative half-life of about 3 weeks. Lasting improvement can only occur with reduction of both existing and newly produced antibody, so improvement occurs very slowly unless the antibodies are physically removed by plasmapheresis, or their catabolism is increased by administration of high doses of exogenous normal human immunoglobulins (IVIG).

2. Pemphigus is notorious in its persistence. Spontaneous remissions typically do not occur, and remissions and relapses are common. Most people require some form of treatment for life.

3. There is only a small repertoire of drugs that are effective at reducing autoantibody synthesis, and the most effective of those are rituximab and cyclophosphamide. The high cost of rituximab can be a barrier to treatment and cyclophosphamide has potential toxicities that cause concern to many treating physicians and can restrict the appropriate use of this drug.

4. All forms of pemphigus are rare, and this prohibits the execution of large, controlled trials. The literature discussing therapeutic regimens is dominated by small series and case reports, which is a weak evidence base for the design of rational treatment. However, we do have excellent animal models of this disease, and understand well the pathophysiology from these studies, which are instrumental in designing our approach to treatment.

Thus, the primary goal of treatment in all forms of pemphigus is to reduce the synthesis of autoantibodies by the immune system. It currently consists of three basic steps:

1. Administration of rituximab with systemic corticosteroids

2. Corticosteroids plus cyclophosphamide

3. Corticosteroids plus cyclophosphamide plus short-term plasmapheresis.

The commitment to the use of cyclophosphamide is a serious one. This drug is extremely effective, but use of this alkylating agent is accompanied by short-term leukopenia and a long-term increased risk of leukemia, lymphoma, and bladder cancer, as well as the risk of sterility in younger patients. The increasing use of rituximab is being explored as a way to avert having to use cyclophosphamide.

Specific investigations

Accuracy of indirect immunofluorescence testing in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Helou J, Allbritton J, Anhalt GJ. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32: 441–7.

Demonstration of IgG autoantibodies on the cell surface of affected epithelium or detection of antigen-specific autoantibodies in the blood. Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by progressively evolving fragile blisters and erosions. Oral involvement essentially ‘always’ occurs and is the major point to differentiate pemphigus vulgaris from pemphigus foliaceus. Histologic changes include suprabasilar acantholysis and cell surface-bound IgG. Circulating autoantibodies are specific for desmoglein 3 alone when lesions are restricted to the mouth and for both desmogleins 3 and 1 when cutaneous lesions are present in addition to oral lesions. Definition of the specificity of desmoglein autoantibodies can be reliably gained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

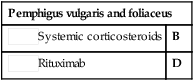

First-line therapies

The first-line therapy for all forms of pemphigus is systemic corticosteroids. Corticosteroids work relatively quickly and are relatively safe when used at appropriate doses for limited periods of time. In the past, regimens of rapidly accelerating doses of corticosteroids were administered, but they were found to be associated with unacceptably high morbidity and mortality risks. Initial treatment should start at 1 mg/kg daily (lean body weight). A good clinical response, defined as a resolution of the majority of existing lesions and absence of newly developing lesions, should be evident within two to 3 months. The dose should then be reduced to 40 mg daily and subsequently tapered over 6 to 9 months, ideally to a maintenance dose of 5 mg every other day. Tapering can be accomplished by reduction of the prednisone by an average of 10 mg/month initially, and 5 mg/month later. There are some advantages to beginning an alternate dose regimen at 40 mg daily, so that monthly reductions would ideally be 40/20 mg alternate days, 40/0 mg, 30/0 mg, 20/0 mg, 15/0 mg, and 10/0 mg, and then 5/0 mg alternate days for maintenance.

Second-line therapies

Third-line therapies

1. Daily orally at 2.5 mg/kg. A single morning dose is followed by aggressive fluid consumption throughout the day to rinse metabolites from the bladder and prevent hemorrhagic cystitis. Weekly complete blood counts and urinalysis are required. With this use, a durable remission can be obtained after 18–24 months of therapy in almost all cases. This exposure probably increases the patient’s lifetime risk of leukemia, lymphoma, or bladder cancer by as much as 5–10% over the normal population. This risk is appreciated some 20–30 years after treatment. Such treatment can also cause sterility in young patients.

2. Monthly intravenous pulses at a dose of 750 mg/m2 body surface area. Monthly intravenous administration reduces the risk of hemorrhagic cystitis, but this intermittent use is not as effective in suppressing the disease.

3. Monthly intravenous administration with lower dose oral daily maintenance. This can also be very effective in inducing a remission.

4. Single, very high-dose immunoablative therapy. This experimental treatment is effective in many autoimmune diseases. It employs a dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide of 200 mg/kg, given over 4 days, which induces profound marrow aplasia. Upon recovery, the patients often experience a complete remission. However, unlike the experience with disorders such as aplastic anemia, where remission may last many years, most patients with pemphigus relapse within 2 years of completion of therapy, limiting its usefulness.

Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids Rituximab

Rituximab

Mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil Azathioprine

Azathioprine High-dose IVIG

High-dose IVIG Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide Cyclophosphamide plus plasmapheresis

Cyclophosphamide plus plasmapheresis Chlorambucil

Chlorambucil