5

Pelvis and Perineum

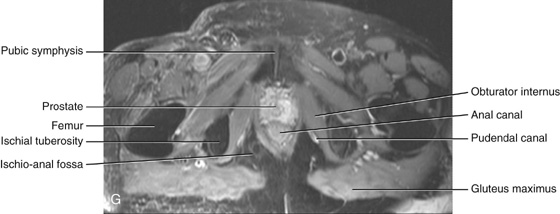

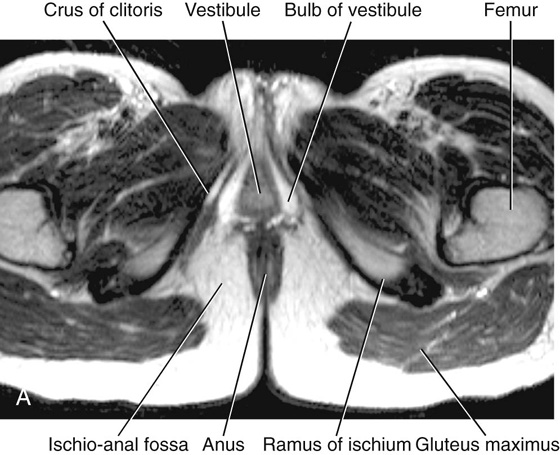

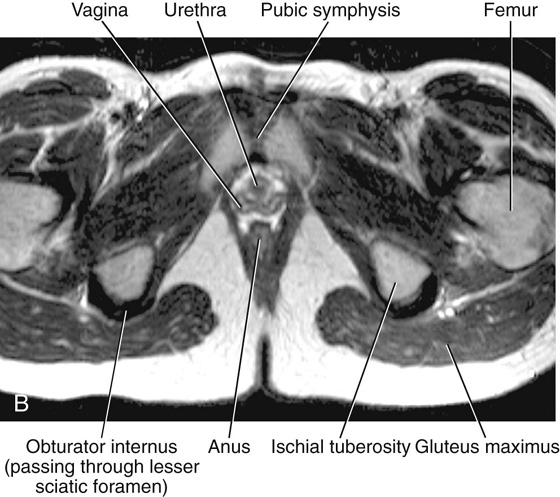

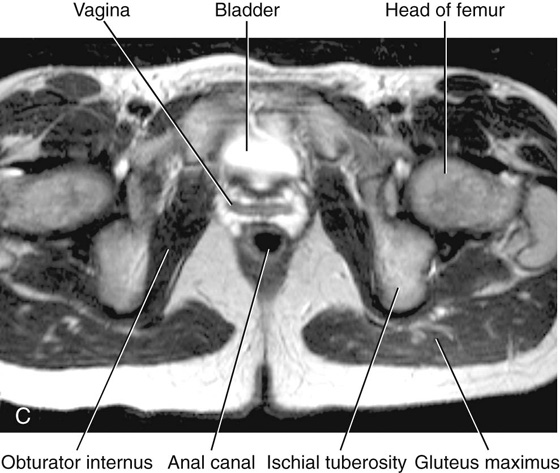

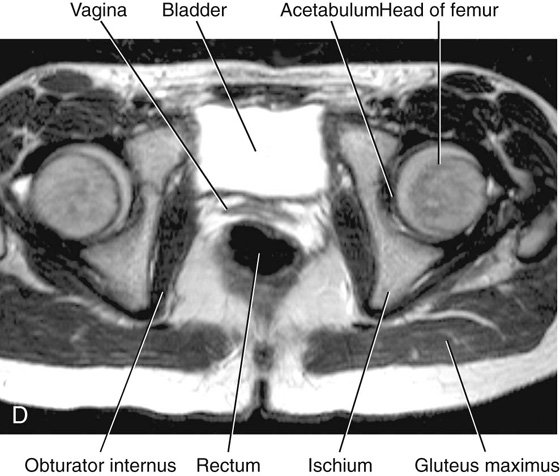

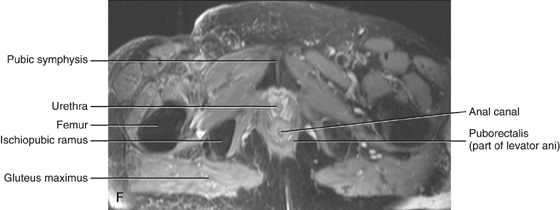

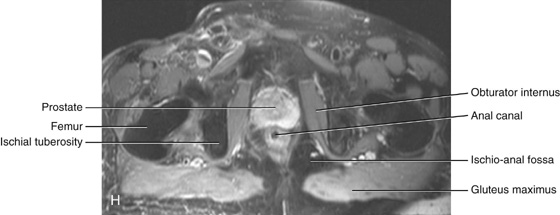

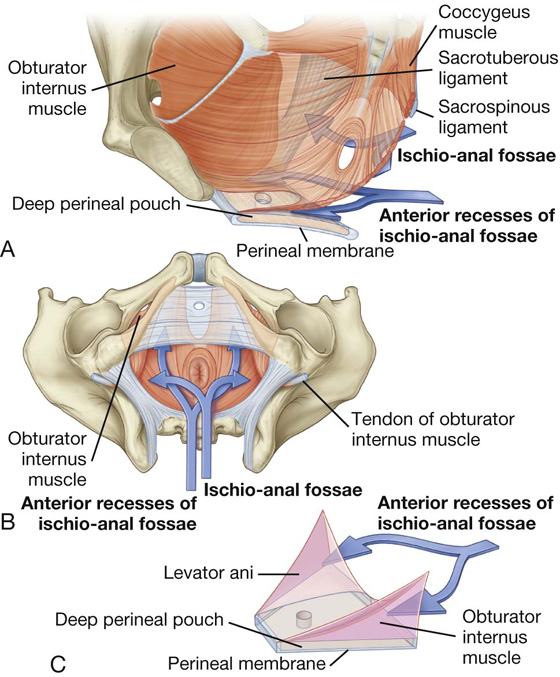

Ischio-anal fossae and their anterior recesses

ADDITIONAL LEARNING RESOURCES FOR CHAPTER 5, PELVIS AND PERINEUM, ON STUDENT CONSULT (www.studentconsult.com)

Image Library—illustrations of pelvic and perineal anatomy, Chapter 5

Image Library—illustrations of pelvic and perineal anatomy, Chapter 5

Self-Assessment (scored)—National Board style multiple-choice questions, Chapter 5

Self-Assessment (scored)—National Board style multiple-choice questions, Chapter 5

Short Questions (not scored)—National Board style multiple-choice questions, Chapter 5

Short Questions (not scored)—National Board style multiple-choice questions, Chapter 5

Interactive Surface Anatomy—interactive surface animations, Chapter 5

Interactive Surface Anatomy—interactive surface animations, Chapter 5

Regional anatomy

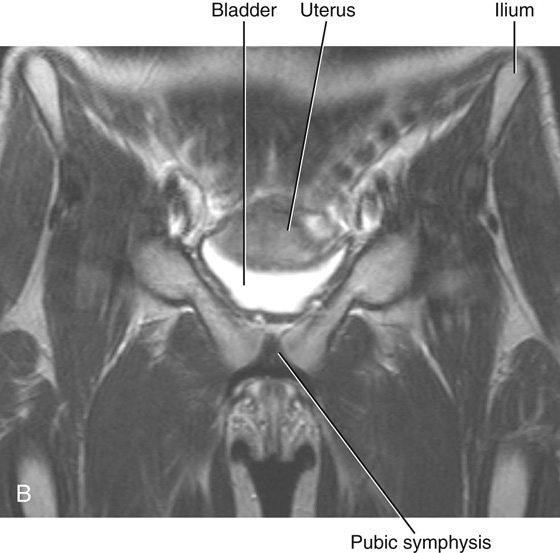

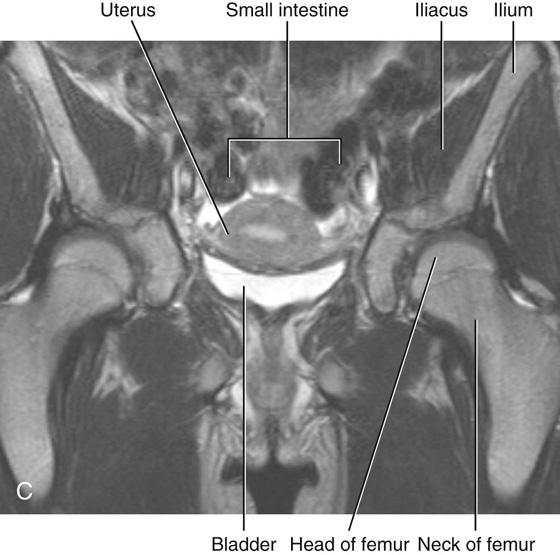

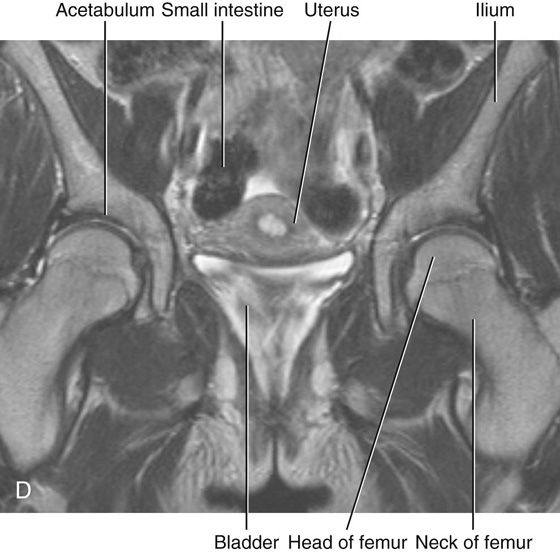

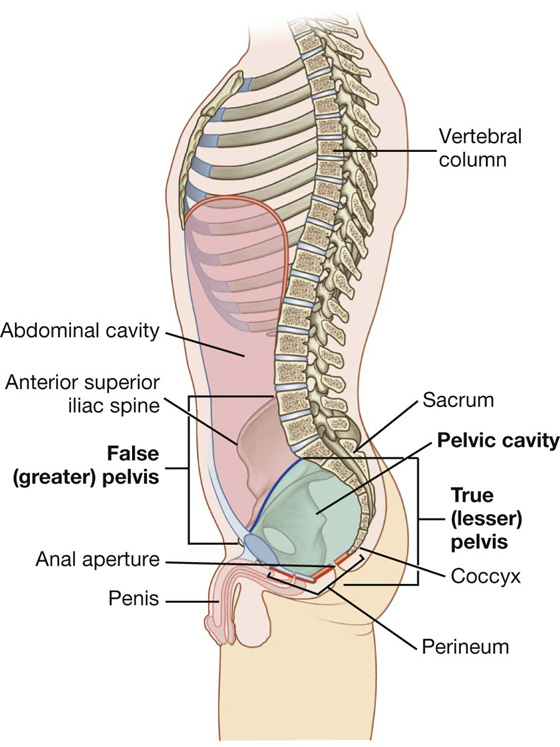

The pelvis and perineum are interrelated regions associated with the pelvic bones and the terminal parts of the vertebral column. The pelvis is divided into two regions (Fig. 5.1):

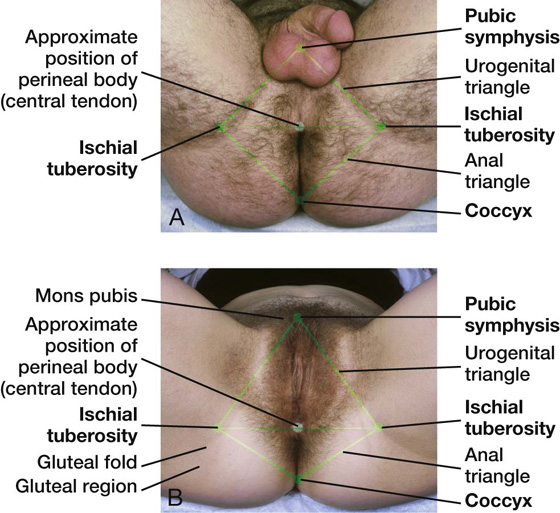

Fig. 5.1 Pelvis and perineum.

The bowl-shaped pelvic cavity (Fig. 5.1) enclosed by the true pelvis consists of the pelvic inlet, walls, and floor. This cavity is continuous superiorly with the abdominal cavity and contains and supports elements of the urinary, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems.

The perineum (Fig. 5.1) is inferior to the floor of the pelvic cavity; its boundaries form the pelvic outlet. The perineum contains and supports the external genitalia and external openings of the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems.

PELVIS

Bones

The bones of the pelvis consist of the right and left pelvic (hip) bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx. The sacrum articulates superiorly with vertebra LV at the lumbosacral joint. The pelvic bones articulate posteriorly with the sacrum at the sacro-iliac joints and with each other anteriorly at the pubic symphysis.

Pelvic bone

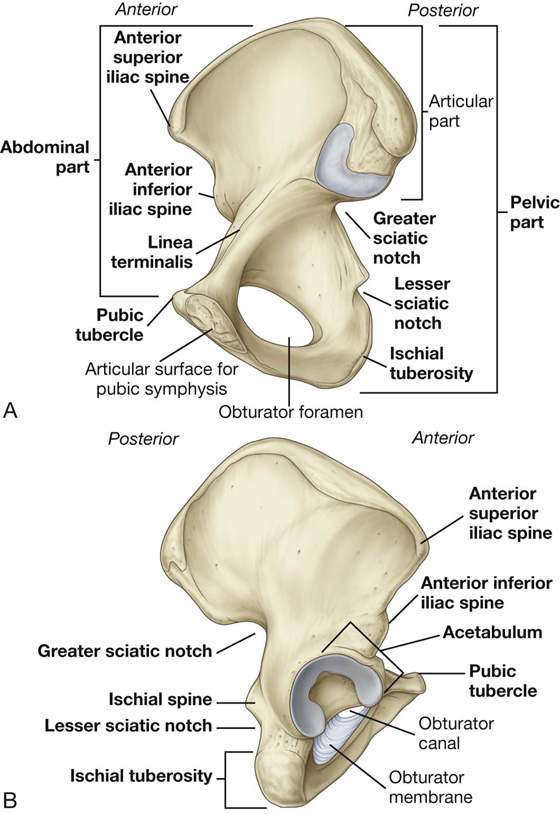

The pelvic bone is irregular in shape and has two major parts separated by an oblique line on the medial surface of the bone (Fig. 5.2A):

Fig. 5.2 Right pelvic bone. A. Medial view. B. Lateral view.

The linea terminalis is the lower two-thirds of this line and contributes to the margin of the pelvic inlet.

The lateral surface of the pelvic bone has a large articular socket, the acetabulum, which together with the head of the femur, forms the hip joint (Fig. 5.2B).

Inferior to the acetabulum is the large obturator foramen, most of which is closed by a flat connective tissue membrane, the obturator membrane. A small obturator canal remains open superiorly between the membrane and adjacent bone, providing a route of communication between the lower limb and the pelvic cavity.

The posterior margin of the bone is marked by two notches separated by the ischial spine (Fig. 5.2):

the greater sciatic notch, and

the greater sciatic notch, and

The posterior margin terminates inferiorly as the large ischial tuberosity.

The irregular anterior margin of the pelvic bone is marked by the anterior superior iliac spine, the anterior inferior iliac spine, and the pubic tubercle.

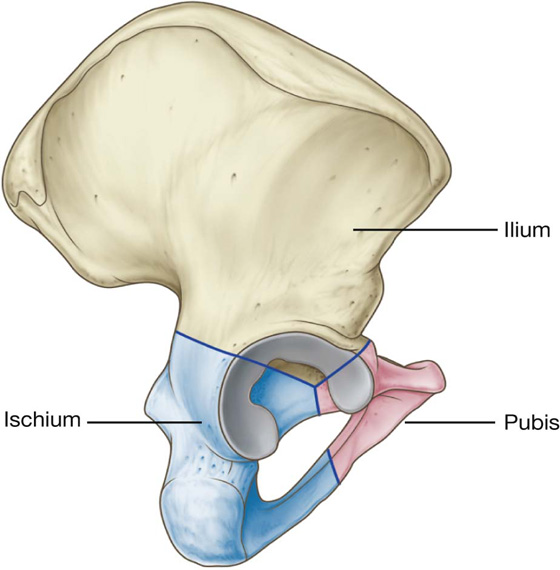

Components of the pelvic bone

Each pelvic bone is formed by three elements: the ilium, pubis, and ischium. At birth, these bones are connected by cartilage in the area of the acetabulum; later, at between 16 and 18 years of age, they fuse into a single bone (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3 Ilium, ischium, and pubis.

Of the three components of the pelvic bone, the ilium is the most superior in position.

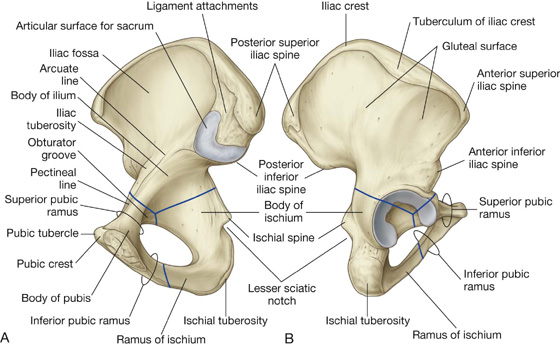

The ilium is separated into upper and lower parts by a ridge on the medial surface (Fig. 5.4A).

Posteriorly, the ridge is sharp and lies immediately superior to the surface of the bone that articulates with the sacrum. This sacral surface has a large L-shaped facet for articulating with the sacrum and an expanded, posterior roughened area for the attachment of the strong ligaments that support the sacro-iliac joint (Fig. 5.4).

Posteriorly, the ridge is sharp and lies immediately superior to the surface of the bone that articulates with the sacrum. This sacral surface has a large L-shaped facet for articulating with the sacrum and an expanded, posterior roughened area for the attachment of the strong ligaments that support the sacro-iliac joint (Fig. 5.4).

Anteriorly, the ridge separating the upper and lower parts of the ilium is rounded and termed the arcuate line (Fig. 5.4).

Anteriorly, the ridge separating the upper and lower parts of the ilium is rounded and termed the arcuate line (Fig. 5.4).

Fig. 5.4 Components of the pelvic bone. A. Medial surface. B. Lateral surface.

The arcuate line forms part of the linea terminalis and the pelvic brim.

The portion of the ilium lying inferiorly to the arcuate line is the pelvic part of the ilium and contributes to the wall of the lesser or true pelvis.

The upper part of the ilium expands to form a flat, fan-shaped “wing,” which provides bony support for the lower abdomen, or false pelvis (Fig. 5.4). This part of the ilium provides attachment for muscles functionally associated with the lower limb. The anteromedial surface of the wing is concave and forms the iliac fossa. The external (gluteal surface) of the wing is marked by lines and roughenings and is related to the gluteal region of the lower limb (Fig. 5.4B).

The entire superior margin of the ilium is thickened to form a prominent crest (the iliac crest), which is the site of attachment for muscles and fascia of the abdomen, back, and lower limb and terminates anteriorly as the anterior superior iliac spine and posteriorly as the posterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 5.4).

A prominent tubercle, tuberculum of iliac crest, projects laterally near the anterior end of the crest; the posterior end of the crest thickens to form the iliac tuberosity (Fig. 5.4).

Inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine of the crest, on the anterior margin of the ilium, is a rounded protuberance called the anterior inferior iliac spine (Fig 5.4). This structure serves as the point of attachment for the rectus femoris muscle of the anterior compartment of the thigh and the iliofemoral ligament associated with the hip joint. A less prominent posterior inferior iliac spine (Fig 5.4) occurs along the posterior border of the sacral surface of the ilium, where the bone angles forward to form the superior margin of the greater sciatic notch.

Clinical app

Bone marrow biopsy

In certain diseases (e.g., leukemia), a sample of bone marrow must be obtained to assess the stage and severity of the problem. The iliac crest is often used for such bone marrow biopsies. The iliac crest lies close to the surface, is palpable, and is easily accessed.

The anterior and inferior part of the pelvic bone is the pubis (Fig. 5.4). It has a body and two arms (rami).

The inferior ramus projects laterally and inferiorly to join with the ramus of the ischium.

The inferior ramus projects laterally and inferiorly to join with the ramus of the ischium.

The ischium is the posterior and inferior part of the pelvic bone (Fig. 5.4). It has:

a ramus that projects anteriorly to join with the inferior ramus of the pubis.

a ramus that projects anteriorly to join with the inferior ramus of the pubis.

The posterior margin of the bone is marked by a prominent ischial spine (Fig. 5.4) that separates the lesser sciatic notch, below, from the greater sciatic notch, above.

The most prominent feature of the ischium is a large tuberosity (the ischial tuberosity) on the posteroinferior aspect of the bone (Fig. 5.4). This tuberosity is an important site for the attachment of lower limb muscles and for supporting the body when sitting.

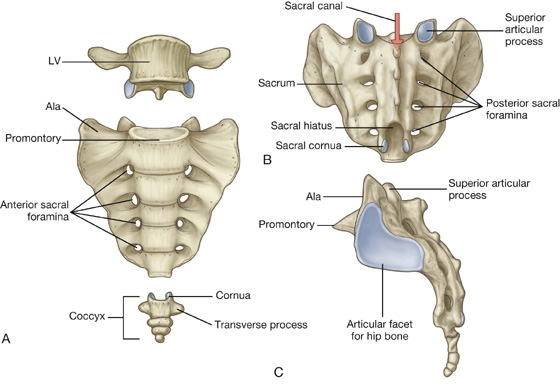

Sacrum

The sacrum, which has the appearance of an inverted triangle, is formed by the fusion of the five sacral vertebrae (Fig. 5.5). The base of the sacrum articulates with vertebra LV, and its apex articulates with the coccyx. Each of the lateral surfaces of the bone bears a large L-shaped facet for articulation with the ilium of the pelvic bone. Posterior to the facet is a large roughened area for the attachment of ligaments that support the sacro-iliac joint. The superior surface of the sacrum is characterized by the superior aspect of the body of vertebra SI and is flanked on each side by an expanded winglike transverse process termed the ala (Fig. 5.5A). The anterior edge of the vertebral body projects forward as the promontory. The anterior surface of the sacrum is concave; the posterior surface is convex. Because the transverse processes of adjacent sacral vertebrae fuse laterally to the position of the intervertebral foramina and laterally to the bifurcation of spinal nerves into posterior and anterior rami, the posterior and anterior rami of spinal nerves S1 to S4 emerge from the sacrum through separate foramina. There are four pairs of anterior sacral foramina on the anterior surface of the sacrum for anterior rami (Fig. 5.5A), and four pairs of posterior sacral foramina on the posterior surface for the posterior rami (Fig. 5.5B). The sacral canal is a continuation of the vertebral canal that terminates as the sacral hiatus.

Fig. 5.5 LV vertebra, sacrum, and coccyx. A. Anterior view. B. Posterior view. C. Lateral view.

Coccyx

The small terminal part of the vertebral column is the coccyx, which consists of four fused coccygeal vertebrae (Fig. 5.5A) and, like the sacrum, has the shape of an inverted triangle. The base of the coccyx is directed superiorly. The superior surface bears a facet for articulation with the sacrum and two horns, or cornua, one on each side, that project upward to articulate or fuse with similar downward-projecting cornua from the sacrum. These processes are modified superior and inferior articular processes that are present on other vertebrae. Each lateral surface of the coccyx has a small rudimentary transverse process, extending from the first coccygeal vertebra. Vertebral arches are absent from coccygeal vertebrae; therefore no bony vertebral canal is present in the coccyx.

Joints

Lumbosacral joints

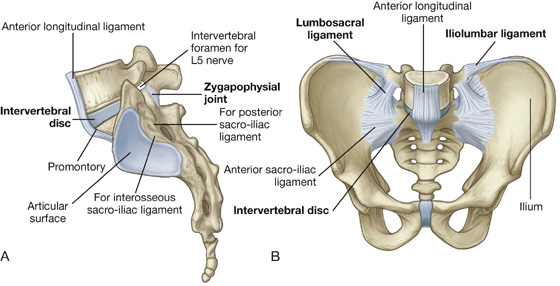

The sacrum articulates superiorly with the lumbar part of the vertebral column. The lumbosacral joints are formed between vertebra LV and the sacrum and consist of (Fig. 5.6A):

an intervertebral disc that joins the bodies of vertebrae LV and SI.

an intervertebral disc that joins the bodies of vertebrae LV and SI.

Fig. 5.6 Lumbosacral joints and associated ligaments. A. Lateral view. B. Anterior view.

These joints are similar to those between other vertebrae, with the exception that the sacrum is angled posteriorly on vertebra LV. As a result, the anterior part of the intervertebral disc between the two bones is thicker than the posterior part.

The lumbosacral joints are reinforced by strong iliolumbar and lumbosacral ligaments that extend from the expanded transverse processes of vertebra LV to the ilium and the sacrum, respectively (Fig. 5.6B).

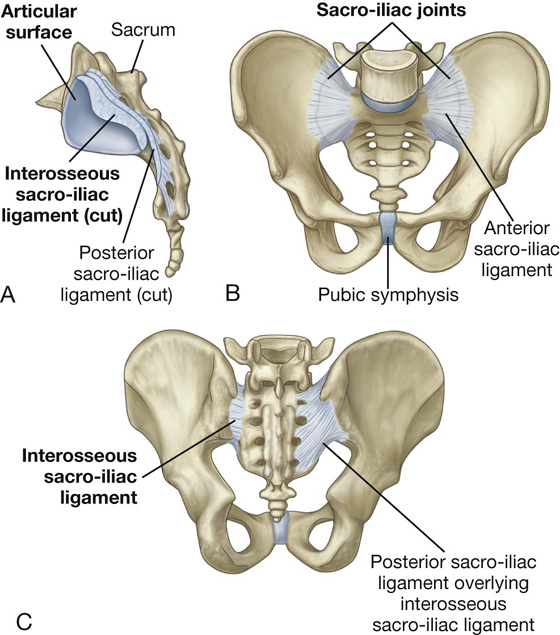

Sacro-iliac joints

The sacro-iliac joints transmit forces from the lower limbs to the vertebral column. They are synovial joints between the L-shaped articular facets on the lateral surfaces of the sacrum and similar facets on the iliac parts of the pelvic bones (Figs. 5.6A, 5.7A). The joint surfaces have an irregular contour and interlock to resist movement. The joints often become fibrous with age and may become completely ossified.

Fig. 5.7 Sacro-iliac joints and associated ligaments. A. Lateral view. B. Anterior view. C. Posterior view.

Each sacro-iliac joint is stabilized by three ligaments:

the anterior sacro-iliac ligament, which is a thickening of the fibrous membrane of the joint capsule and runs anteriorly and inferiorly to the joint (Figs. 5.6B, 5.7B);

the anterior sacro-iliac ligament, which is a thickening of the fibrous membrane of the joint capsule and runs anteriorly and inferiorly to the joint (Figs. 5.6B, 5.7B);

the interosseus sacro-iliac ligament, which is the largest, strongest ligament of the three, is positioned immediately posterosuperior to the joint and attaches to adjacent expansive roughened areas on the ilium and sacrum, thereby filling the gap between the two bones (Fig. 5.7A and 5.7C); and

the interosseus sacro-iliac ligament, which is the largest, strongest ligament of the three, is positioned immediately posterosuperior to the joint and attaches to adjacent expansive roughened areas on the ilium and sacrum, thereby filling the gap between the two bones (Fig. 5.7A and 5.7C); and

the posterior sacro-iliac ligament, which covers the interosseus sacro-iliac ligament (Fig. 5.7C).

the posterior sacro-iliac ligament, which covers the interosseus sacro-iliac ligament (Fig. 5.7C).

Clinical app

Common problems with the sacro-iliac joints

The sacro-iliac joints have both fibrous and synovial components, and as with many weight-bearing joints, degenerative changes may occur and cause pain and discomfort in the sacro-iliac region. In addition, disorders associated with the major histocompatibility complex antigen HLA B27, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease, can produce specific inflammatory changes within these joints.

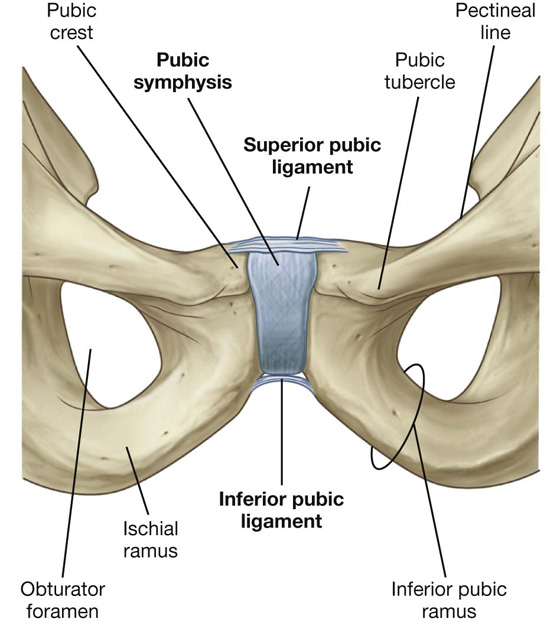

Pubic symphysis joint

The pubic symphysis lies anteriorly between the adjacent surfaces of the pubic bones (Fig. 5.8). Each of the joint’s surfaces is covered by hyaline cartilage and is linked across the midline to adjacent surfaces by fibrocartilage. The joint is surrounded by interwoven layers of collagen fibers and the two major ligaments associated with it are (Fig. 5.8):

the superior pubic ligament, located above the joint; and

the superior pubic ligament, located above the joint; and

the inferior pubic ligament, located below it.

the inferior pubic ligament, located below it.

Fig. 5.8 Pubic symphysis and associated ligaments.

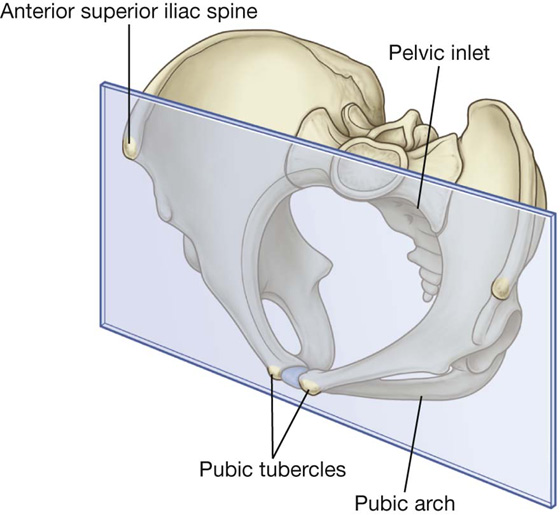

Orientation

In the anatomical position, the pelvis is oriented so that the front edge of the top of the pubic symphysis and the anterior superior iliac spines lie in the same vertical plane (Fig. 5.9). As a consequence, the pelvic inlet, which marks the entrance to the pelvic cavity, is tilted to face anteriorly, and the bodies of the pubic bones and the pubic arch are positioned in a nearly horizontal plane facing the ground.

Fig. 5.9 Orientation of the pelvis (anatomical position).

Gender differences

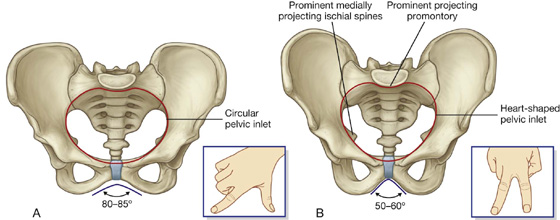

The pelvises of women and men differ in a number of ways, many of which have to do with the passing of a baby through a woman’s pelvic cavity during childbirth.

The pelvic inlet in women is circular (Fig. 5.10A) compared with the more heart-shaped pelvic inlet (Fig. 5.10B) in men. The more circular shape is partly caused by the less distinct promontory and broader alae in women.

The pelvic inlet in women is circular (Fig. 5.10A) compared with the more heart-shaped pelvic inlet (Fig. 5.10B) in men. The more circular shape is partly caused by the less distinct promontory and broader alae in women.

The angle formed by the two arms of the pubic arch is larger in women (80° to 85°) than it is in men (50° to 60°) (Fig. 5.10).

The angle formed by the two arms of the pubic arch is larger in women (80° to 85°) than it is in men (50° to 60°) (Fig. 5.10).

True pelvis

The true pelvis is cylindrical and has an inlet, a wall, and an outlet. The inlet is open, whereas the pelvic floor closes the outlet and separates the pelvic cavity, above, from the perineum, below.

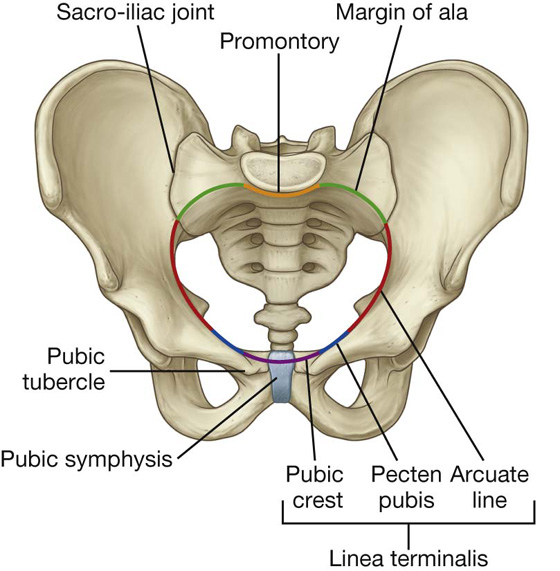

Pelvic inlet

The pelvic inlet is the circular opening between the abdominal cavity and the pelvic cavity through which structures traverse between the abdomen and pelvic cavity. It is completely surrounded by bones and joints (Fig. 5.11). The promontory of the sacrum protrudes into the inlet, forming its posterior margin in the midline. On either side of the promontory, the margin is formed by the alae of the sacrum. The margin of the pelvic inlet then crosses the sacro-iliac joint and continues along the linea terminalis (i.e., the arcuate line, the pecten pubis, or pectineal line, and the pubic crest) to the pubic symphysis.

Fig. 5.11 Pelvic inlet.

Pelvic wall

The walls of the pelvic cavity consist of the sacrum, the coccyx, the pelvic bones inferior to the linea terminalis, two ligaments, and two muscles.

Clinical app

Pelvic fracture

The pelvis can be viewed as a series of anatomical rings. There are three bony rings and four fibro-osseous rings. The major bony pelvic ring consists of parts of the sacrum, ilium, and pubis, which forms the pelvic inlet. Two smaller subsidiary bony rings are the obturator foraminae. The greater and lesser sciatic foraminae, formed by the greater and lesser sciatic notches and the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments form the four fibro-osseous rings. It is not possible to break one side of a bony ring without breaking the other side of the ring, which in clinical terms means that if a fracture is demonstrated on one side, a second fracture should always be suspected.

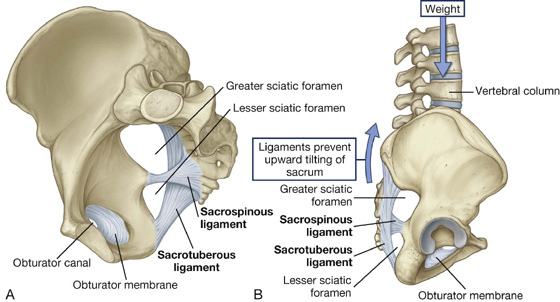

Ligaments of the pelvic wall

The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments (Fig. 5.12A) are major components of the lateral pelvic walls that help define the apertures between the pelvic cavity and adjacent regions through which structures pass.

The smaller of the two, the sacrospinous ligament, is triangular, with its apex attached to the ischial spine and its base attached to the related margins of the sacrum and the coccyx (Fig. 5.12A).

The smaller of the two, the sacrospinous ligament, is triangular, with its apex attached to the ischial spine and its base attached to the related margins of the sacrum and the coccyx (Fig. 5.12A).

The sacrotuberous ligament is also triangular and is superficial to the sacrospinous ligament. Its base has a broad attachment that extends from the posterior superior iliac spine of the pelvic bone, along the dorsal aspect and the lateral margin of the sacrum, and onto the dorsolateral surface of the coccyx. Laterally, the apex of the ligament is attached to the medial margin of the ischial tuberosity (Fig. 5.12A).

The sacrotuberous ligament is also triangular and is superficial to the sacrospinous ligament. Its base has a broad attachment that extends from the posterior superior iliac spine of the pelvic bone, along the dorsal aspect and the lateral margin of the sacrum, and onto the dorsolateral surface of the coccyx. Laterally, the apex of the ligament is attached to the medial margin of the ischial tuberosity (Fig. 5.12A).

These ligaments stabilize the sacrum on the pelvic bones by resisting the upward tilting of the inferior aspect of the sacrum (Fig. 5.12B). They also convert the greater and lesser sciatic notches of the pelvic bone into foramina (Fig. 5.12A, B).

The greater sciatic foramen lies superior to the sacrospinous ligament and the ischial spine.

The greater sciatic foramen lies superior to the sacrospinous ligament and the ischial spine.

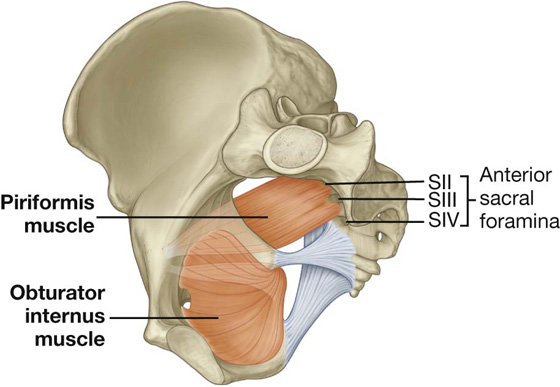

Muscles of the pelvic wall

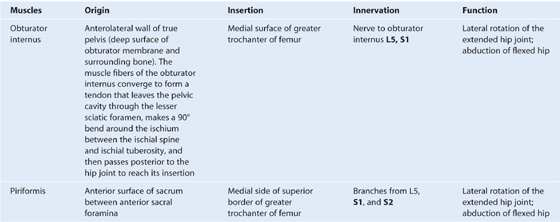

Two muscles, the obturator internus and the piriformis, contribute to the lateral walls of the pelvic cavity. These muscles originate in the pelvic cavity but attach peripherally to the femur (Table 5.1, Fig. 5.13).

Table 5.1 Muscles of the pelvic walls (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

Fig. 5.13 Obturator internus and piriformis muscles (medial view of right side of pelvis).

Apertures in the pelvic wall

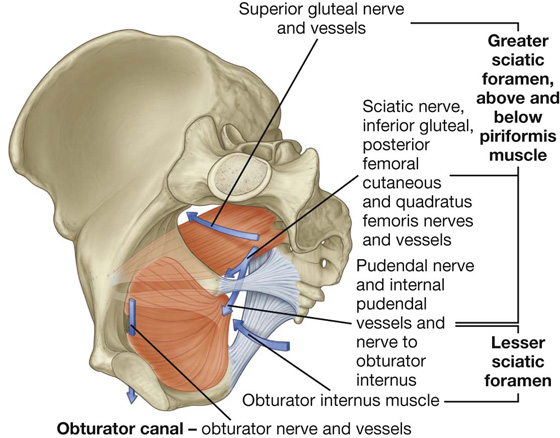

Each lateral pelvic wall has three major apertures through which structures pass between the pelvic cavity and other regions (Fig. 5.14):

the greater sciatic foramen, and

the greater sciatic foramen, and

Fig. 5.14 Apertures in the pelvic wall.

At the top of the obturator foramen is the obturator canal, which is bordered by the obturator membrane, the associated obturator muscles, and the superior pubic ramus (Fig. 5.14). The obturator nerve and vessels pass from the pelvic cavity to the thigh through this canal.

The greater sciatic foramen is a major route of communication between the pelvic cavity and the lower limb (Fig. 5.14). It is formed by the greater sciatic notch in the pelvic bone, the sacrotuberous and the sacrospinous ligaments, and the spine of the ischium.

The piriformis muscle passes through the greater sciatic foramen, dividing it into two parts.

The superior gluteal nerves and vessels pass through the foramen above the piriformis.

The superior gluteal nerves and vessels pass through the foramen above the piriformis.

The lesser sciatic foramen is formed by the lesser sciatic notch of the pelvic bone, the ischial spine, the sacrospinous ligament, and the sacrotuberous ligament (Fig. 5.14). The tendon of the obturator internus muscle passes through this foramen to enter the gluteal region of the lower limb.

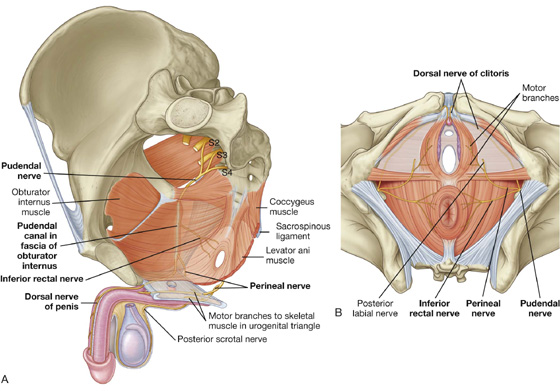

Because the lesser sciatic foramen is positioned below the attachment of the pelvic floor, it acts as a route of communication between the perineum and the gluteal region. The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels pass between the pelvic cavity (above the pelvic floor) and the perineum (below the pelvic floor), by first passing out of the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen, then looping around the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament to pass through the lesser sciatic foramen to enter the perineum.

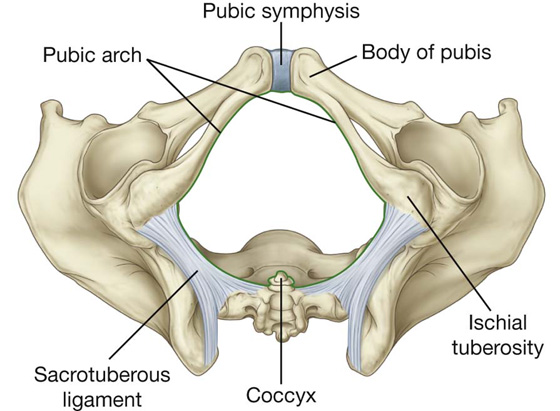

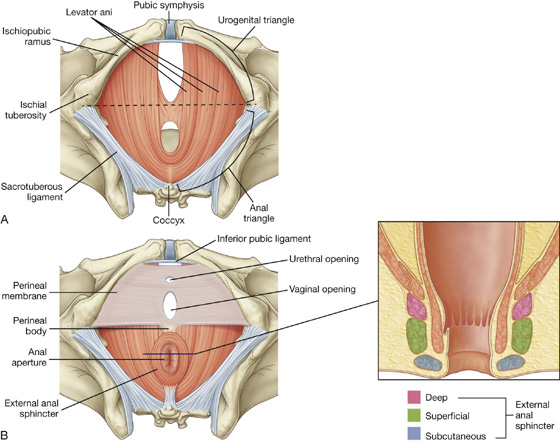

Pelvic outlet

The pelvic outlet is diamond shaped, with the anterior part of the diamond defined predominantly by bone and the posterior part mainly by ligaments (Fig. 5.15). In the midline anteriorly, the boundary of the pelvic outlet is the pubic symphysis.

Fig. 5.15 Pelvic outlet.

From the ischial tuberosities, the boundaries continue posteriorly and medially along the sacrotuberous ligament on both sides to the coccyx.

Terminal parts of the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts and the vagina pass through the pelvic outlet.

Clinical app

Pelvic measurements in obstetrics

Accurate measurements of a women’s pelvic inlet and outlet can help in predicting the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery during childbirth. These measurements include:

the sagittal inlet (between the promontory and the top of the pubic symphysis);

the sagittal inlet (between the promontory and the top of the pubic symphysis);

the maximum transverse diameter of the inlet;

the maximum transverse diameter of the inlet;

the bispinous outlet (the distance between ischial spines); and

the bispinous outlet (the distance between ischial spines); and

The area enclosed by the boundaries of the pelvic outlet and below the pelvic floor is the perineum.

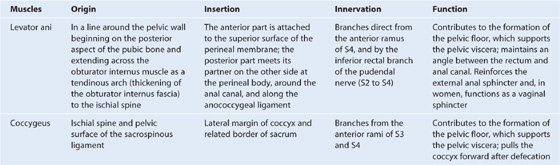

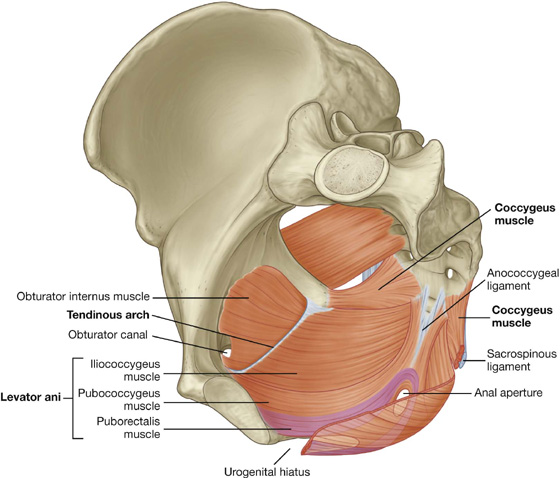

Pelvic floor

The pelvic floor is formed by the pelvic diaphragm and, in the anterior midline, the perineal membrane and the muscles in the deep perineal pouch. The pelvic diaphragm is formed by the levator ani and the coccygeus muscles from both sides. The pelvic floor separates the pelvic cavity, above, from the perineum, below.

The pelvic diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm is the muscular part of the pelvic floor. Shaped like a bowl or funnel and attached superiorly to the pelvic walls, it consists of the levator ani and the coccygeus muscles (Table 5.2, Fig. 5.16).

Table 5.2 Muscles of the pelvic diaphragm

Fig. 5.16 Pelvic diaphragm.

The pelvic diaphragm’s circular line of attachment to the cylindrical pelvic wall passes, on each side, between the greater sciatic foramen and the lesser sciatic foramen. Thus:

The two levator ani muscles originate from each side of the pelvic wall, course medially and inferiorly, and join together in the midline. The attachment to the pelvic wall follows the circular contour of the wall and includes (Fig. 5.16):

the posterior aspect of the body of the pubic bone,

the posterior aspect of the body of the pubic bone,

At the midline, the muscles blend together posterior to the vagina in women and around the anal aperture in both sexes. Posterior to the anal aperture, the muscles come together as a ligament or raphe called the anococcygeal ligament (anococcygeal body) and attaches to the coccyx (Fig. 5.16). Anteriorly, the muscles are separated by a U-shaped defect or gap termed the urogenital hiatus. The margins of this hiatus merge with the walls of the associated viscera and with muscles in the deep perineal pouch below. The hiatus allows the urethra (in both men and women), and the vagina (in women), to pass through the pelvic diaphragm (Fig. 5.16).

The levator ani muscles are divided into at least three collections of muscle fibers, based on site of origin and relationship to viscera in the midline: the pubococcygeus, the puborectalis, and the iliococcygeus muscles (Fig. 5.16).

The levator ani muscles help support the pelvic viscera and maintain closure of the rectum and vagina.

Clinical app

Defecation

At the beginning of defecation, closure of the larynx stabilizes the diaphragm and intra-abdominal pressure is increased by contraction of abdominal wall muscles. As defecation proceeds, the puborectalis muscle surrounding the anorectal junction relaxes, which straightens the anorectal angle. Both the internal and the external anal sphincters also relax to allow feces to move through the anal canal. Normally, the puborectal sling maintains an angle of about 90° between the rectum and the anal canal and acts as a “pinch valve” to prevent defecation. When the puborectalis muscle relaxes, the anorectal angle increases to about 130° to 140°.

The fatty tissue of the ischio-anal fossa allows for changes in the position and size of the anal canal and anus during defecation. During evacuation, the anorectal junction moves down and back and the pelvic floor usually descends slightly.

During defecation, the circular muscles of the rectal wall undergo a wave of contraction to push feces toward the anus. As feces emerge from the anus, the longitudinal muscles of the rectum and levator ani bring the anal canal back up, the feces are expelled, and the anus and rectum return to their normal positions.

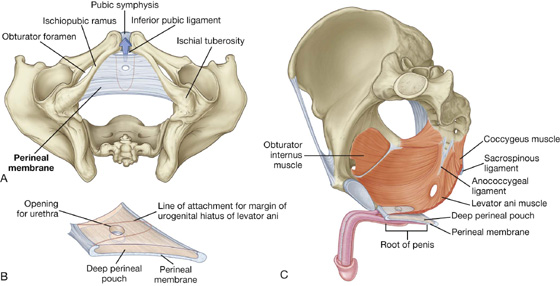

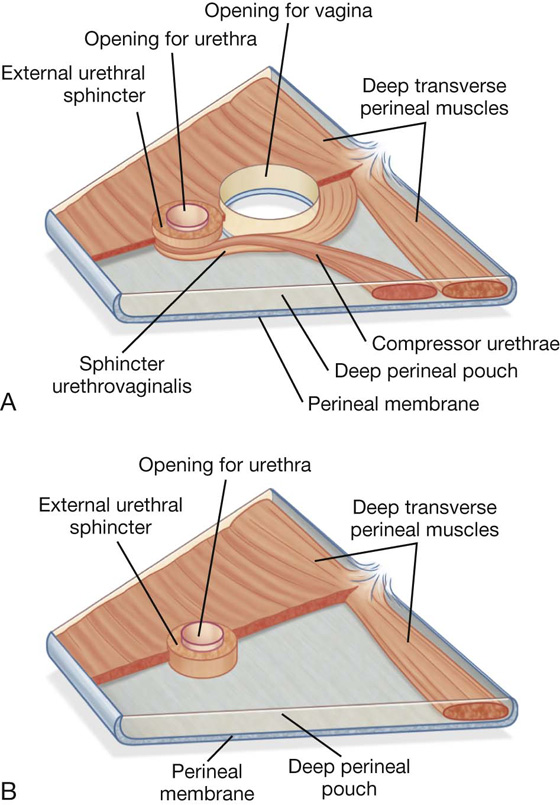

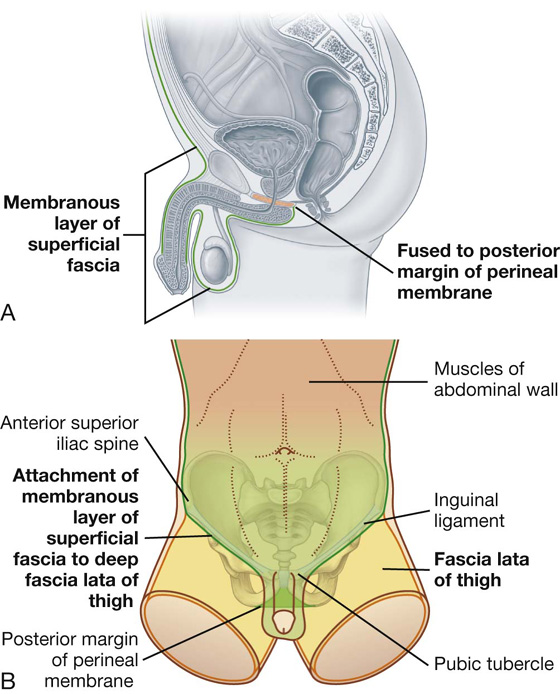

The perineal membrane and deep perineal pouch

The perineal membrane is a thick fascial, triangular structure attached to the bony framework of the pubic arch (Fig. 5.17A). It is oriented in the horizontal plane and has a free posterior margin. Anteriorly, there is a small gap between the membrane and the inferior pubic ligament (a ligament associated with the pubic symphysis).

Fig. 5.17 Perineal membrane and deep perineal pouch. A. Inferior view. B. Superolateral view. C. Medial view.

The perineal membrane is related above to a thin space called the deep perineal pouch (deep perineal space) (Fig. 5.17B), which contains a layer of skeletal muscle and various neurovascular elements.

The deep perineal pouch is open above and is not separated from more superior structures by a distinct layer of fascia. The parts of perineal membrane and structures in the deep perineal pouch, enclosed by the urogenital hiatus above, therefore contribute to the pelvic floor and support elements of the urogenital system in the pelvic cavity, even though the perineal membrane and deep perineal pouch are usually considered parts of the perineum.

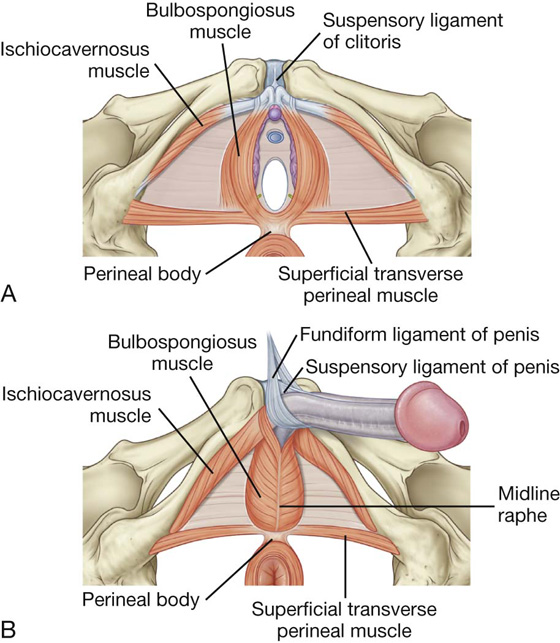

The perineal membrane and adjacent pubic arch provide attachment for the roots of the external genitalia and the muscles associated with them (Fig. 5.17C).

The urethra penetrates vertically through a circular hiatus in the perineal membrane as it passes from the pelvic cavity, above, to the perineum, below. In women, the vagina also passes through a hiatus in the perineal membrane just posterior to the urethral hiatus.

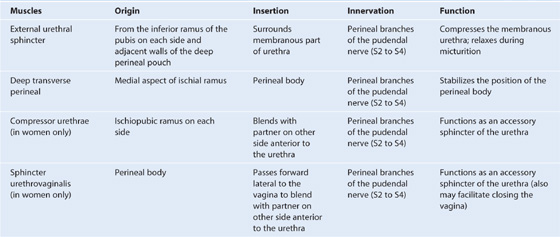

Within the deep perineal pouch, a sheet of skeletal muscle functions as a sphincter, mainly for the urethra, and as a stabilizer of the posterior edge of the perineal membrane (Table 5.3, Fig. 5.18).

Table 5.3 Muscles within the deep perineal pouch

Fig. 5.18 Muscles in the deep perineal pouch. A. In women. B. In men.

Anteriorly, a group of muscle fibers surround the urethra and collectively form the external urethral sphincter (Fig. 5.18).

Anteriorly, a group of muscle fibers surround the urethra and collectively form the external urethral sphincter (Fig. 5.18).

Two additional groups of muscle fibers are associated with the urethra and vagina in women (Fig. 5.18A). One group forms the sphincter urethrovaginalis, which surrounds the urethra and vagina as a unit. The second group forms the compressor urethrae, on each side, which originate from the ischiopubic rami and meet anterior to the urethra. Together with the external urethral sphincter, the sphincter urethrovaginalis and compressor urethrae facilitate closing of the urethra.

Two additional groups of muscle fibers are associated with the urethra and vagina in women (Fig. 5.18A). One group forms the sphincter urethrovaginalis, which surrounds the urethra and vagina as a unit. The second group forms the compressor urethrae, on each side, which originate from the ischiopubic rami and meet anterior to the urethra. Together with the external urethral sphincter, the sphincter urethrovaginalis and compressor urethrae facilitate closing of the urethra.

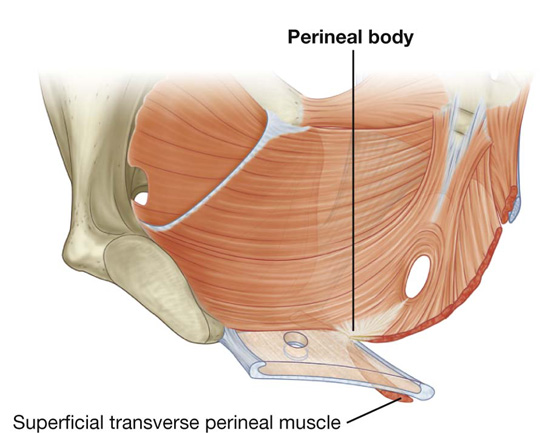

Perineal body

The perineal body is an ill-defined but important connective tissue structure into which muscles of the pelvic floor and the perineum attach (Fig. 5.19). It is positioned in the midline along the posterior border of the perineal membrane, to which it attaches. The posterior end of the urogenital hiatus in the levator ani muscles is also connected to it.

Fig. 5.19 Perineal body.

The deep transverse perineal muscles intersect at the perineal body; in women, the sphincter urethrovaginalis also attaches to the perineal body. Other muscles that connect to the perineal body include the external anal sphincter, the superficial transverse perineal muscles, and the bulbospongiosus muscles of the perineum.

Clinical app

Episiotomy

During childbirth the perineal body may be stretched and torn. Traditionally it was felt that if a perineal tear is likely, the obstetrician may proceed with an episiotomy. This is a procedure in which an incision is made in the perineal body to allow the head of the fetus to pass through the vagina. There are two types of episiotomies: a median episiotomy cuts through the perineal body, while a mediolateral episiotomy is an incision 45° from the midline. The maternal benefits of this procedure have been thought to be less trauma to the perineum and decreased pelvic floor dysfunction. However, more recent evidence suggests that an episiotomy should not be performed routinely. Review of data has failed to show a decrease in pelvic floor damage with routine use of episiotomies.

Viscera

The pelvic viscera include parts of the gastrointestinal system, the urinary system, and the reproductive system. The viscera are arranged in the midline, from front to back; the neurovascular supply is through branches that pass medially from vessels and nerves associated with the pelvic walls.

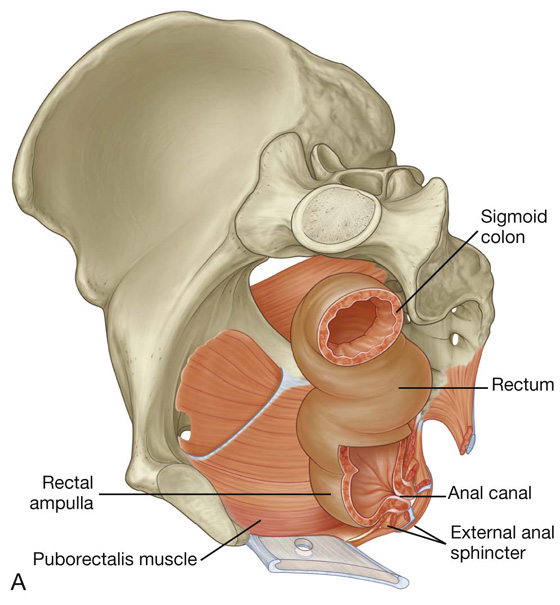

Gastrointestinal system

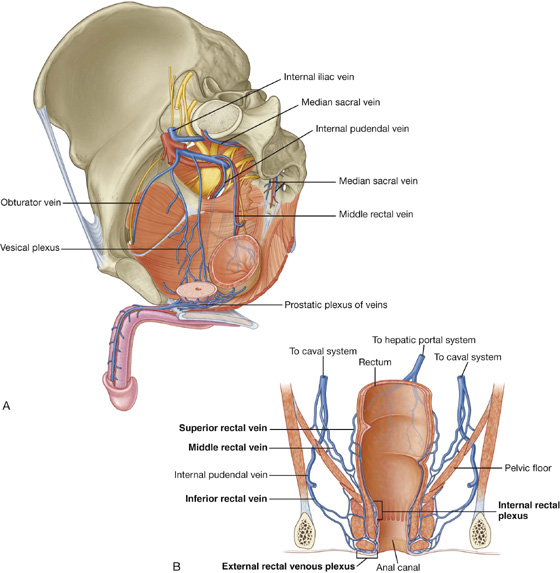

Pelvic parts of the gastrointestinal system consist mainly of the rectum and the anal canal, although the terminal part of the sigmoid colon is also in the pelvic cavity (Fig. 5.20).

Fig. 5.20 Rectum and anal canal. A. Left pelvic bone removed. B. Longitudinal section.

Rectum

The rectum is continuous:

above, with the sigmoid colon at about the level of vertebra SIII; and

above, with the sigmoid colon at about the level of vertebra SIII; and

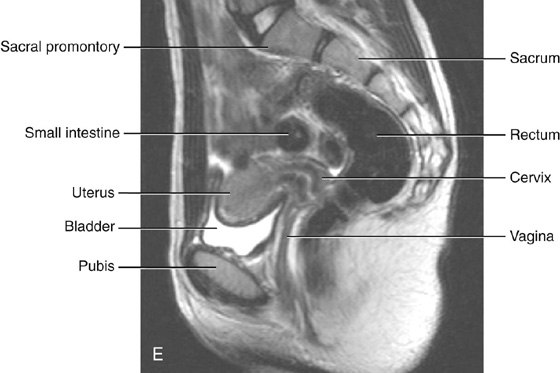

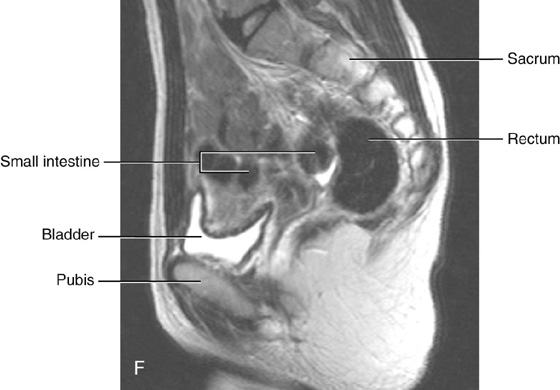

The rectum, the most posterior element of the pelvic viscera, is immediately anterior to, and follows the concave contour of the sacrum (Fig. 5.20A).

The anorectal junction is pulled forward (perineal flexure) by the action of the puborectalis part of the levator ani muscle, so the anal canal moves in a posterior direction as it passes inferiorly through the pelvic floor.

In addition to conforming to the general curvature of the sacrum in the anteroposterior plane, the rectum has three lateral curvatures; the upper and lower curvatures to the right and the middle curvature to the left. The lower part of the rectum is expanded to form the rectal ampulla. Finally, unlike the colon, the rectum lacks distinct taeniae coli muscles, omental appendices, and sacculations (haustra of the colon).

Digital rectal examination

A digital rectal examination (DRE) is performed by placing the gloved and lubricated index finger into the rectum through the anus. The anal mucosa can be palpated for abnormal masses, and in women, the posterior wall of the vagina and the cervix can be palpated. In men, the prostate can be evaluated for any extraneous nodules or masses.

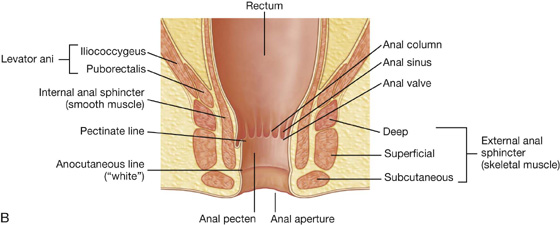

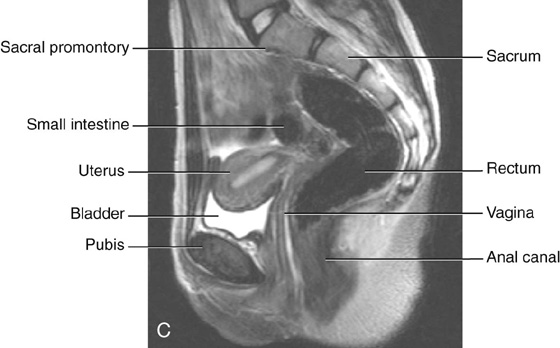

Anal canal

The anal canal begins at the terminal end of the rectal ampulla where it narrows at the pelvic floor (Fig. 5.20B). It terminates as the anus after passing through the perineum. As it passes through the pelvic floor, the anal canal is surrounded along its entire length by the internal and external anal sphincters, which normally keep it closed (Fig. 5.20B).

The lining of the anal canal bears a number of characteristic structural features that reflect the approximate position of the anococcygeal membrane in the fetus (which closes the terminal end of the developing gastrointestinal system in the fetus) and the transition from gastrointestinal mucosa to skin in the adult (Fig. 5.20B).

Clinical app

Carcinoma of the colon and rectum

Carcinoma of the colon and rectum (colorectum) is a common disease.

Given the position of the colon and rectum in the abdominopelvic cavity and its proximity to other organs, it is extremely important to accurately stage colorectal tumors: a tumor in the pelvis, for example, could invade the uterus or bladder.

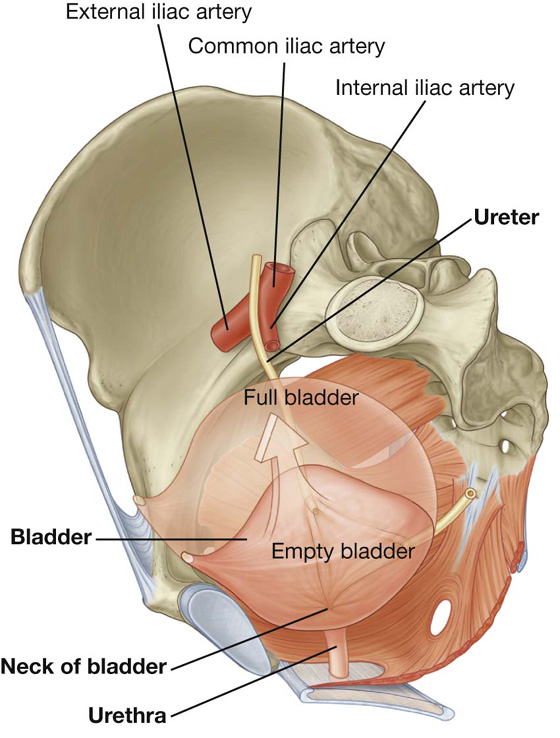

Urinary system

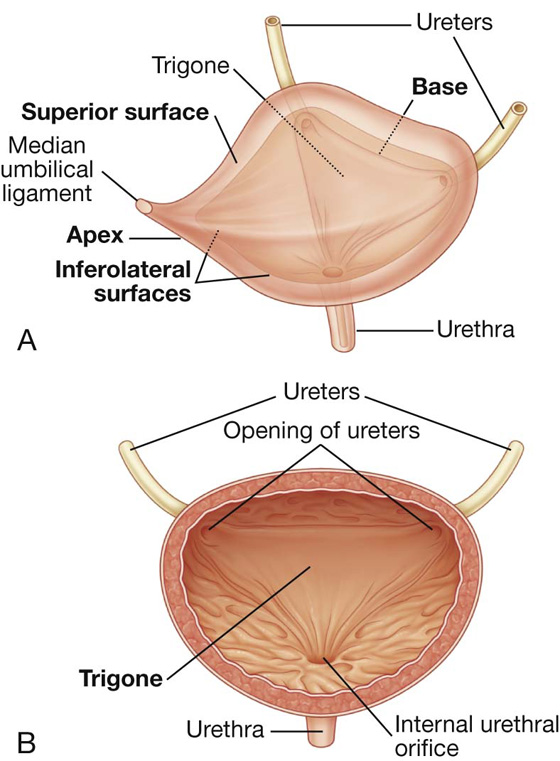

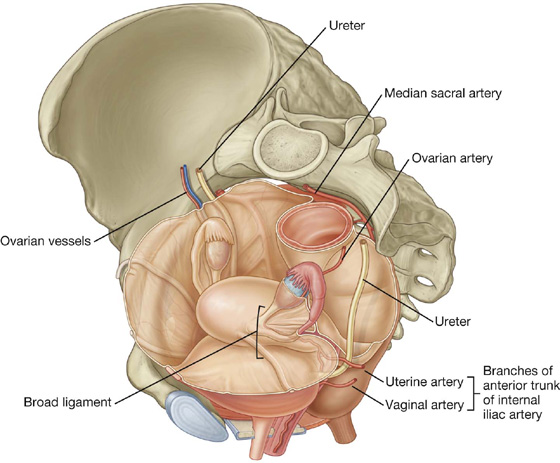

The pelvic parts of the urinary system consist of the terminal parts of the ureters, the bladder, and the proximal part of the urethra (Fig. 5.21).

Fig. 5.21 Pelvic parts of the urinary system.

Ureters

The ureters enter the pelvic cavity from the abdomen by passing through the pelvic inlet (Fig. 5.21). On each side, the ureter crosses the pelvic inlet and enters the pelvic cavity in the area anterior to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery. From this point, it continues along the pelvic wall and floor to join the base of the bladder.

In the pelvis, the ureter is crossed by:

the ductus deferens in men, and

the ductus deferens in men, and

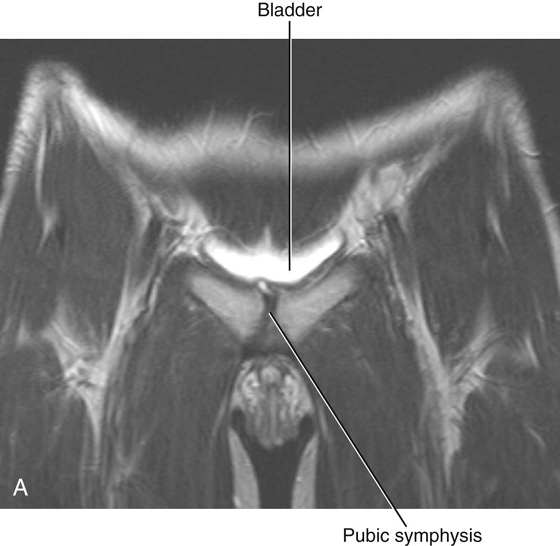

Bladder

The bladder is the most anterior element of the pelvic viscera. Although it is entirely situated in the pelvic cavity when empty, it expands superiorly into the abdominal cavity when full (see Fig. 5.21).

The empty bladder is shaped like a three-sided pyramid that has tipped over to lie on one of its margins (see Fig. 5.22A). It has an apex, a base, a superior surface, and two inferolateral surfaces (see Fig. 5.22A).

The base of the bladder is shaped like an inverted triangle and faces posteroinferiorly. The two ureters enter the bladder at each of the upper corners of the base, and the urethra drains inferiorly from the lower corner of the base (Fig. 5.22A, B). Inside, the mucosal lining on the base of the bladder is smooth and firmly attached to the underlying smooth muscle coat of the wall—unlike elsewhere in the bladder where the mucosa is folded and loosely attached to the wall. The smooth triangular area between the openings of the ureters and urethra on the inside of the bladder is known as the trigone (Fig. 5.22B).

The base of the bladder is shaped like an inverted triangle and faces posteroinferiorly. The two ureters enter the bladder at each of the upper corners of the base, and the urethra drains inferiorly from the lower corner of the base (Fig. 5.22A, B). Inside, the mucosal lining on the base of the bladder is smooth and firmly attached to the underlying smooth muscle coat of the wall—unlike elsewhere in the bladder where the mucosa is folded and loosely attached to the wall. The smooth triangular area between the openings of the ureters and urethra on the inside of the bladder is known as the trigone (Fig. 5.22B).

The neck of the bladder surrounds the origin of the urethra at the point where the two inferolateral surfaces and the base intersect (see Fig. 5.21).

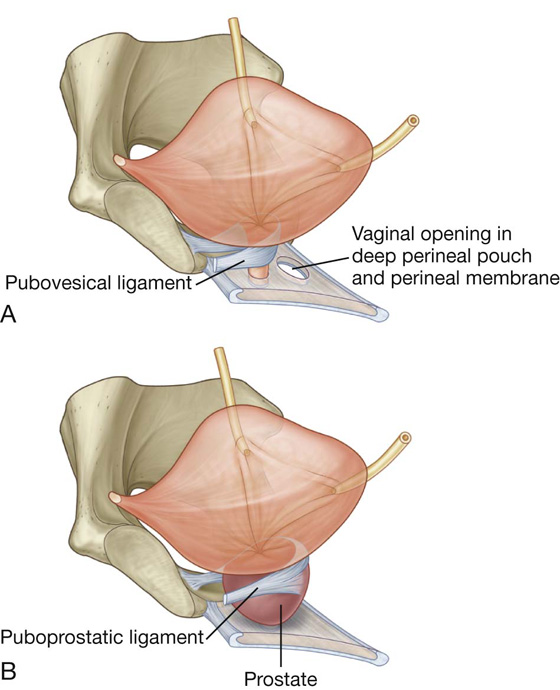

The neck is the most inferior part of the bladder and also the most “fixed” part. It is anchored into position by a pair of tough fibromuscular bands, which connect the neck and pelvic part of the urethra to the posteroinferior aspect of each pubic bone.

In women, these fibromuscular bands are termed pubovesical ligaments (Fig. 5.23A). Together with the perineal membrane and associated muscles, the levator ani muscles, and the pubic bones, these ligaments help support the bladder.

In women, these fibromuscular bands are termed pubovesical ligaments (Fig. 5.23A). Together with the perineal membrane and associated muscles, the levator ani muscles, and the pubic bones, these ligaments help support the bladder.

In men, the paired fibromuscular bands are known as puboprostatic ligaments because they blend with the fibrous capsule of the prostate, which surrounds the neck of the bladder and adjacent part of the urethra (Fig. 5.23B).

In men, the paired fibromuscular bands are known as puboprostatic ligaments because they blend with the fibrous capsule of the prostate, which surrounds the neck of the bladder and adjacent part of the urethra (Fig. 5.23B).

Although the bladder is considered to be pelvic in the adult, it has a higher position in children. At birth, the bladder is almost entirely abdominal; the urethra begins approximately at the upper margin of the pubic symphysis. With age, the bladder descends until after puberty when it assumes the adult position.

Clinical app

Bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is the most common tumor of the urinary tract and is usually a disease of the sixth and seventh decades, although there is an increasing trend for younger patients to develop this disease.

Bladder tumors may spread through the bladder wall and invade local structures, including the rectum, uterus (in women), and the lateral walls of the pelvic cavity. Prostatic involvement is not uncommon in male patients.

Large bladder tumors may produce complications, including invasion and obstruction of the ureters. Ureteric obstruction can then obstruct the kidneys and induce kidney failure.

Bladder stones

In some patients, small calculi (stones) form in the kidneys. These may pass down the ureter, causing ureteric obstruction, and into the bladder, where insoluble salts further precipitate on these small calculi to form larger calculi. Often, these patients develop (or may already have) problems with bladder emptying, which leaves residual urine in the bladder. This urine may become infected and alter the pH of the urine, permitting further precipitation of insoluble salts.

Clinical app

Suprapubic catheterization

In certain instances it is necessary to catheterize the bladder through the anterior abdominal wall. For example, when the prostate is markedly enlarged and it is impossible to pass a urethral catheter into the bladder. The bladder is a retroperitoneal structure and when full lies adjacent to the anterior abdominal wall.

The procedure of suprapubic catheterization is straightforward and involves the passage of a small catheter through the abdominal wall in the midline above the pubic symphysis. The catheter passes into the bladder without compromising other structures and allows drainage.

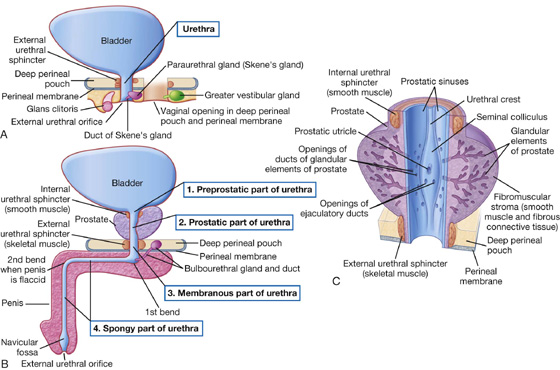

Urethra

The urethra begins at the base of the bladder and ends with an external opening in the perineum. The paths taken by the urethra differ significantly in women and men.

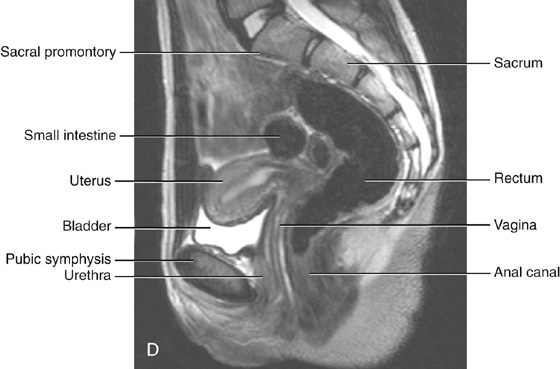

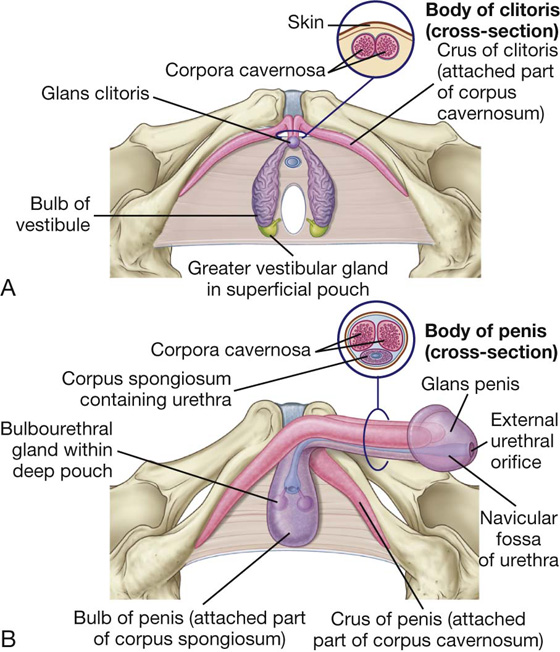

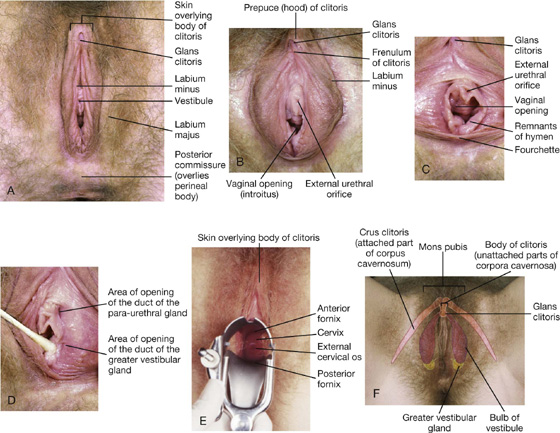

In women, the urethra is short, being about 4 cm long. It travels a slightly curved course as it passes inferiorly through the pelvic floor into the perineum, where it passes through the deep perineal pouch and perineal membrane before opening in the vestibule that lies between the labia minora (Fig. 5.24A).

Fig. 5.24 Urethra. A. In women. B. In men. C. Prostatic part of the urethra in men.

The urethral opening is anterior to the vaginal opening in the vestibule. The inferior aspect of the urethra is bound to the anterior surface of the vagina. Two small para-urethral mucous glands (Skene’s glands) are associated with the lower end of the urethra. Each drains via a duct that opens onto the lateral margin of the external urethral orifice.

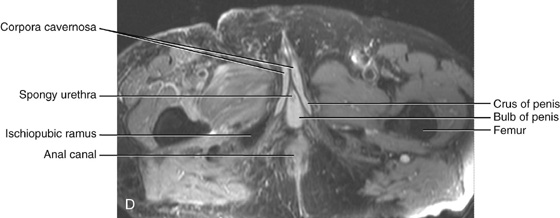

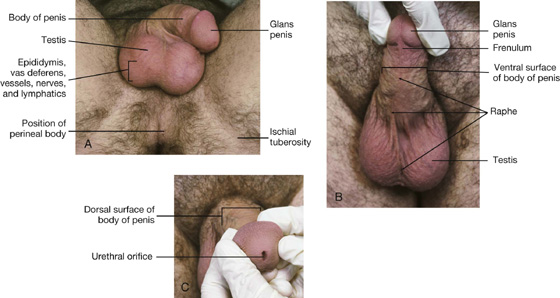

In men, the urethra is long, about 20 cm, and bends twice along its course (Fig. 5.24B). Beginning at the base of the bladder and passing inferiorly through the prostate, it passes through the deep perineal pouch and perineal membrane and immediately enters the root of the penis. As the urethra exits the deep perineal pouch, it bends forward to course anteriorly in the root of the penis. When the penis is flaccid, the urethra makes another bend, this time inferiorly, when passing from the root to the body of the penis. During erection, the bend between the root and body of the penis disappears.

The urethra in men is divided into preprostatic, prostatic, membranous, and spongy parts (see Fig. 5.24B).

Preprostatic part. The preprostatic part of the urethra is about 1 cm long, extends from the base of the bladder to the prostate, and is associated with a circular cuff of smooth muscle fibers (the internal urethral sphincter) (see Fig. 5.24B). Contraction of this sphincter prevents retrograde movement of semen into the bladder during ejaculation.

Prostatic part. The prostatic part of the urethra (see Fig. 5.24C) is 3 to 4 cm long and is surrounded by the prostate. In this region, the lumen of the urethra is marked by a longitudinal midline fold of mucosa (the urethral crest). The depression on each side of the crest is the prostatic sinus; the ducts of the prostate empty into these two sinuses.

Midway along its length, the urethral crest is enlarged to form a somewhat circular elevation (the seminal colliculus) (see Fig. 5.24C). In men, the seminal colliculus is used to determine the position of the prostate gland during transurethral transection of the prostate.

A small blind-ended pouch—the prostatic utricle (thought to be the homologue of the uterus in women)—opens onto the center of the seminal colliculus (see Fig. 5.24C). On each side of the prostatic utricle is the opening of the ejaculatory duct of the male reproductive system. Therefore the connection between the urinary and reproductive tracts in men occurs in the prostatic part of the urethra.

Membranous part. The membranous part of the urethra is narrow and passes through the deep perineal pouch (see Fig. 5.24B). During its transit through this pouch, the urethra, in both men and women, is surrounded by skeletal muscle of the external urethral sphincter.

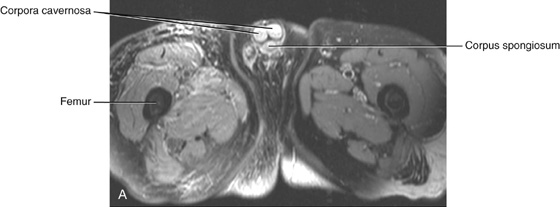

Spongy urethra. The spongy urethra is surrounded by erectile tissue (the corpus spongiosum) of the penis. It is enlarged to form a bulb at the base of the penis and again at the end of the penis to form the navicular fossa (see Fig. 5.24B). The two bulbourethral glands in the deep perineal pouch are part of the male reproductive system and open into the bulb of the spongy urethra. The external urethral orifice is the sagittal slit at the end of the penis.

Clinical app

Bladder infection

The relatively short length of the urethra in women makes them more susceptible than men to bladder infection. The primary symptom of urinary tract infection in women is usually inflammation of the bladder (cystitis). In children under 1 year of age, infection from the bladder may spread via the ureters to the kidneys, where it can produce renal damage and ultimately lead to renal failure. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary.

Urethral catheterization

Urethral catheterization is often performed to drain urine from a patient’s bladder when the patient is unable to micturate. When inserting urinary catheters, it is important to appreciate the gender anatomy of the patient.

In men the spongy urethra angles superiorly to pass through the perineal membrane and into the pelvis. Just inferior to the perineal membrane, the wall of the urethral bulb is relatively thin and can be damaged when inserting catheters or doing cystoscopy. In women, these procedures are much simpler because the urethra is short and straight.

Reproductive system

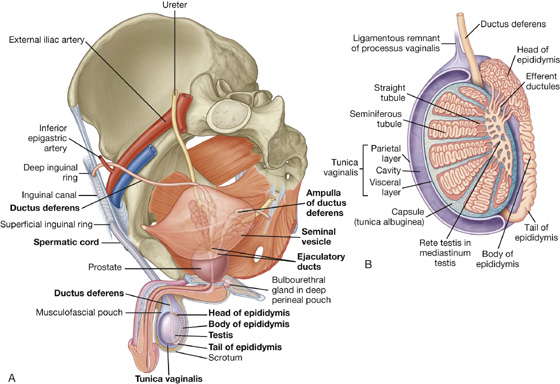

In men

The reproductive system in men has components in the abdomen, pelvis, and perineum (Fig. 5.25A). The major components are a testis, epididymis, ductus deferens, and ejaculatory duct on each side, and the urethra and penis in the midline. In addition, three types of accessory glands are associated with the system:

Fig. 5.25 Reproductive system in men. A. Overview. B. Testis and surrounding structures.

a pair of seminal vesicles, and

a pair of seminal vesicles, and

a pair of bulbourethral glands.

a pair of bulbourethral glands.

The design of the reproductive system in men is basically a series of ducts and tubules. The arrangement of parts and linkage to the urinary tract reflects its embryological development.

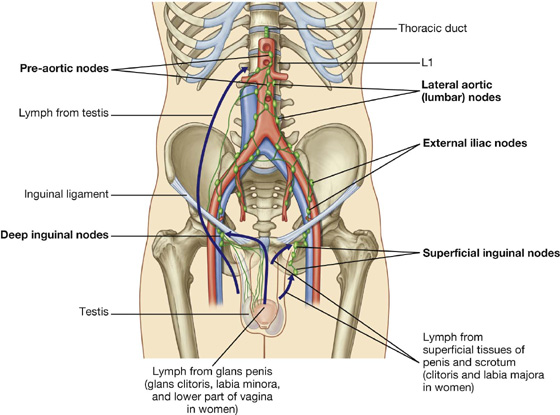

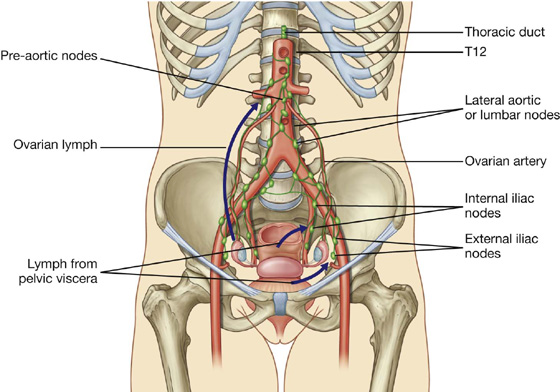

The testes originally develop high on the posterior abdominal wall and then descend, normally before birth, through the inguinal canal in the anterior abdominal wall and into the scrotum of the perineum. During descent, the testes carry their vessels, lymphatics, and nerves, as well as their principal drainage ducts, the ductus deferens (vas deferens) with them. The lymph drainage of the testes is therefore to the lateral aortic or lumbar nodes and pre-aortic nodes in the abdomen, and not to the inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes.

Each ellipsoid-shaped testis is enclosed within the end of an elongated musculofascial pouch, which is continuous with the anterior abdominal wall and projects into the scrotum. The spermatic cord is the tube-shaped connection between the pouch in the scrotum and the abdominal wall (Fig. 5.25A).

The sides and anterior aspect of the testis are covered by a closed sac of peritoneum (the tunica vaginalis), which originally connected to the abdominal cavity (Fig. 5.25B). Normally after testicular descent, the connection closes, leaving a fibrous remnant.

Each testis (Fig. 5.25B) is composed of seminiferous tubules and interstitial tissue surrounded by a thick connective tissue capsule (the tunica albuginea). Spermatozoa are produced by the seminiferous tubules. The 400 to 600 highly coiled seminiferous tubules are modified at each end to become straight tubules, which connect to a collecting chamber (the rete testis) in a thick, vertically oriented linear wedge of connective tissue (the mediastinum testis), projecting from the capsule into the posterior aspect of the gonad (Fig. 5.25B). Approximately 12 to 20 efferent ductules originate from the upper end of the rete testis, penetrate the capsule, and connect with the epididymis.

Clinical app

Undescended testes

Around the seventh month of gestation, the testes begin their descent from the posterior abdominal wall through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. During the descent, the testes may arrest (undescended testes) or they may end up in an ectopic position. Undescended/ectopic testes are associated with infertility and increased risk of testicular tumors.

Clinical app

Hydrocele of the testis

A hydrocele of the testis is an accumulation of fluid within the cavity of the tunica vaginalis. Hydroceles are typically unilateral and in most cases their cause is unknown, although they may occur secondary to physical trauma, infection, or tumor.

Clinical app

Testicular tumors

Tumors of the testis account for a small percentage of malignancies in men. However, they generally occur in younger patients (between 20 and 40 years of age).

Early diagnosis of testicular tumor is extremely important. Abnormal lumps can be detected by palpation and diagnosis can be made using ultrasound.

Surgical removal of the malignant testis is often carried out using an inguinal approach. The testis is not usually removed through a scrotal incision because it is possible to spread tumor cells into the subcutaneous tissues of the scrotum, which has a different lymphatic drainage than the testis.

The epididymis is a single, long coiled duct that courses along the posterolateral side of the testis (Fig. 5.25B). It has two distinct components:

The ductus deferens is a long muscular duct that transports spermatozoa from the tail of the epididymis in the scrotum to the ejaculatory duct in the pelvic cavity (see Fig. 5.25A). It ascends in the scrotum as a component of the spermatic cord and passes through the inguinal canal in the anterior abdominal wall.

After passing through the deep inguinal ring, the ductus deferens bends medially around the lateral side of the inferior epigastric artery and crosses the external iliac artery and the external iliac vein at the pelvic inlet to enter the pelvic cavity (see Fig. 5.25A).

The duct descends medially on the pelvic wall, deep to the peritoneum, and crosses the ureter posterior to the bladder. It continues inferomedially along the base of the bladder, anterior to the rectum, almost to the midline, where it is joined by the duct of the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct (see Fig. 5.25A).

Between the ureter and ejaculatory duct, the ductus deferens expands to form the ampulla of the ductus deferens. The ejaculatory duct penetrates through the prostate gland to connect with the prostatic urethra.

Clinical app

Vasectomy

The ductus deferens transports spermatozoa from the tail of the epididymis in the scrotum to the ejaculatory duct in the pelvic cavity. Because it has a thick smooth muscle wall, it can be easily palpated in the spermatic cord between the testes and the superficial inguinal ring. Also, because it can be accessed through skin and superficial fascia, it is amenable to surgical dissection and surgical division. When this is carried out bilaterally (vasectomy), the patient is rendered sterile—this is a useful method for male contraception.

Each seminal vesicle is an accessory gland of the male reproductive system that develops as a blind-ended tubular outgrowth from the ductus deferens (see Fig. 5.25A). The tube is coiled with numerous pocket-like outgrowths and is encapsulated by connective tissue to form an elongate structure situated between the bladder and rectum. The gland is immediately lateral to and follows the course of the ductus deferens at the base of the bladder.

The duct of the seminal vesicle joins the ductus deferens to form the ejaculatory duct (see Fig. 5.25A). Secretions from the seminal vesicle contribute significantly to the volume of the ejaculate (semen).

The prostate is an unpaired accessory structure of the male reproductive system that surrounds the urethra in the pelvic cavity (see Fig. 5.25A). It lies immediately inferior to the bladder, posterior to the pubic symphysis, and anterior to the rectum.

The prostate is shaped like an inverted rounded cone with a larger base, which is continuous above with the neck of the bladder, and a narrower apex, which rests below on the pelvic floor. The inferolateral surfaces of the prostate are in contact with the levator ani muscles that together cradle the prostate between them.

The prostate develops as 30 to 40 individual complex glands, which grow from the urethral epithelium into the surrounding wall of the urethra. Collectively, these glands enlarge the wall of the urethra into what is known as the prostate; however, the individual glands retain their own ducts, which empty independently into the prostatic sinuses on the posterior aspect of the urethral lumen.

Secretions from the prostate, together with secretions from the seminal vesicles, contribute to the formation of semen during ejaculation.

The ejaculatory ducts pass almost vertically in an anteroinferior direction through the posterior aspect of the prostate to open into the prostatic urethra.

Clinical app

Prostate problems

Prostate cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies in men, and often the disease is advanced at diagnosis. Prostate cancer typically occurs in the peripheral regions of the prostate and is relatively asymptomatic. In many cases, it is diagnosed by a digital rectal examination and by blood tests, which include serum acid phosphatase and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA). In rectal examinations, the tumorous prostate feels “rock” hard. The diagnosis is usually made by obtaining a number of biopsies of the prostate.

Benign prostatic hypertrophy is a disease of the prostate that occurs with increasing age in most men (Fig. 5.26). It generally involves the more central regions of the prostate, which gradually enlarge. The prostate feels “bulky” on digital rectal examination. Owing to the more central hypertrophic change of the prostate, the urethra is compressed, and a urinary outflow obstruction develops in a number of patients. With time, the bladder may become hypertrophied in response to the urinary outflow obstruction. In some male patients, the obstruction becomes so severe that urine cannot be passed and transurethral or suprapubic catheterization is necessary. Despite being a benign disease, benign prostatic hypertrophy can therefore have a marked effect on the daily lives of many patients.

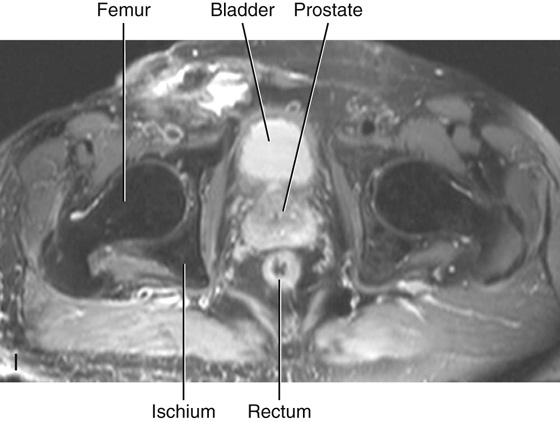

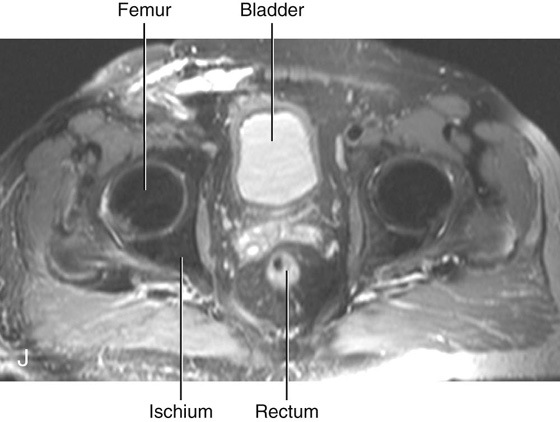

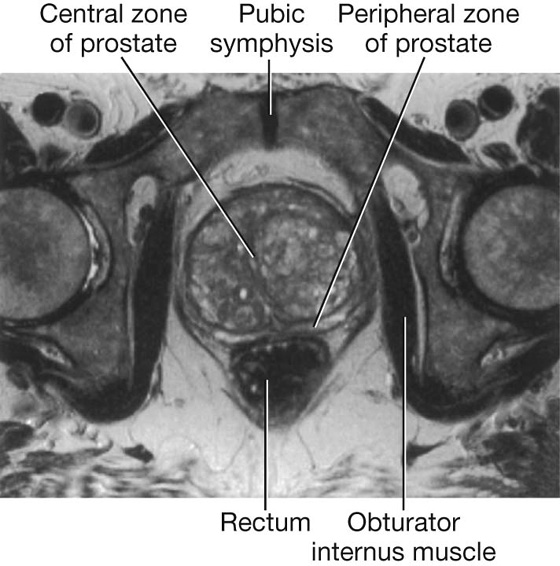

Fig. 5.26 Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of benign prostatic hypertrophy.

The bulbourethral glands (see Fig. 5.25A), one on each side, are small, pea-shaped mucous glands situated within the deep perineal pouch. They are lateral to the membranous part of the urethra. The duct from each gland passes inferomedially through the perineal membrane to open into the bulb of the spongy urethra at the root of the penis.

Together with small glands positioned along the length of the spongy urethra, the bulbourethral glands contribute to lubrication of the urethra and the pre-ejaculatory emission from the penis.

In women

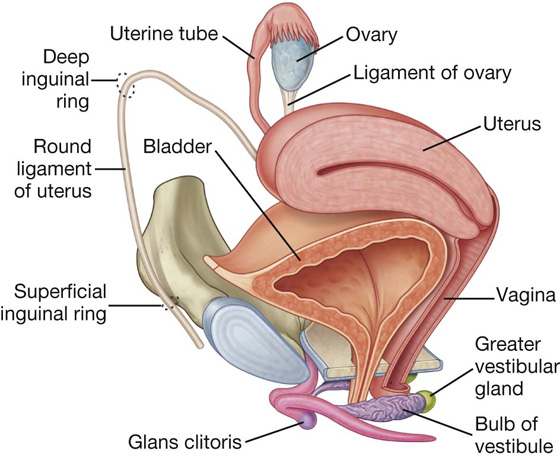

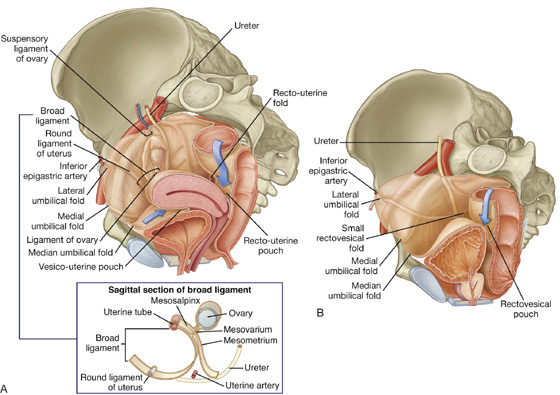

The reproductive tract in women is contained mainly in the pelvic cavity and perineum, although during pregnancy, the uterus expands into the abdomen cavity. Major components of the system consist of (Fig. 5.27):

Fig. 5.27 Reproductive system in women.

a uterus, vagina, and clitoris in the midline.

a uterus, vagina, and clitoris in the midline.

In addition, a pair of accessory glands (the greater vestibular glands) are associated with the tract.

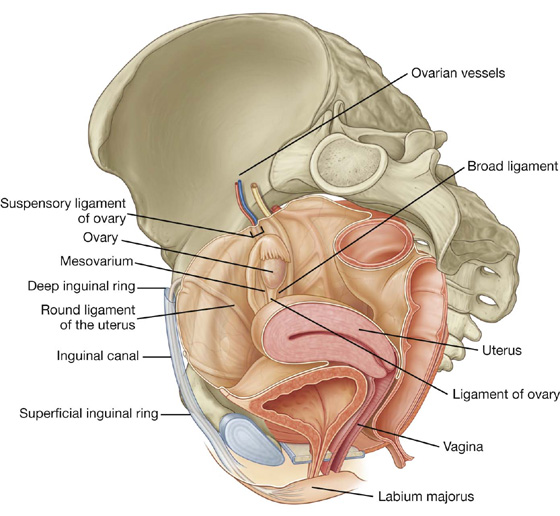

Like the testes in men, the ovaries develop high on the posterior abdominal wall and then descend before birth, bringing with them their vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. Unlike the testes, the ovaries do not migrate through the inguinal canal into the perineum, but stop short and assume a position on the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity (Fig. 5.28).

Fig. 5.28 Ovaries and broad ligament.

The ovaries lie adjacent to the lateral pelvic wall just inferior to the pelvic inlet. Each of the two almond-shaped ovaries is about 3 cm long and is suspended by a mesentery (the mesovarium) that is a posterior extension of the broad ligament.

Clinical app

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer remains one of the major challenges in oncology. The ovaries contain numerous cell types, all of which can undergo malignant change and require different imaging and treatment protocols and ultimately have different prognoses. Ovarian cancer may occur at any age, but more typically it occurs in older women.

Many factors have been linked with the development of ovarian tumors, including a strong family history.

Cancer of the ovaries may spread via the blood and lymphatics, and frequently metastasizes directly into the peritoneal cavity. Such direct peritoneal cavity spread allows the passage of tumor cells along the paracolic gutters and over the liver from where this disease may disseminate easily. Unfortunately, many patients already have metastatic and diffuse disease at the time of diagnosis.

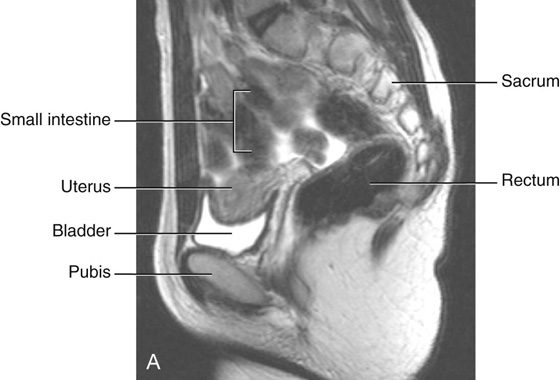

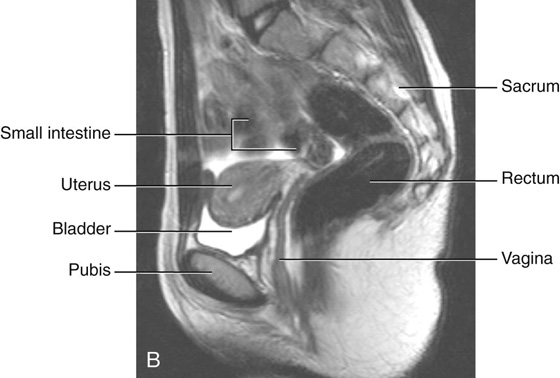

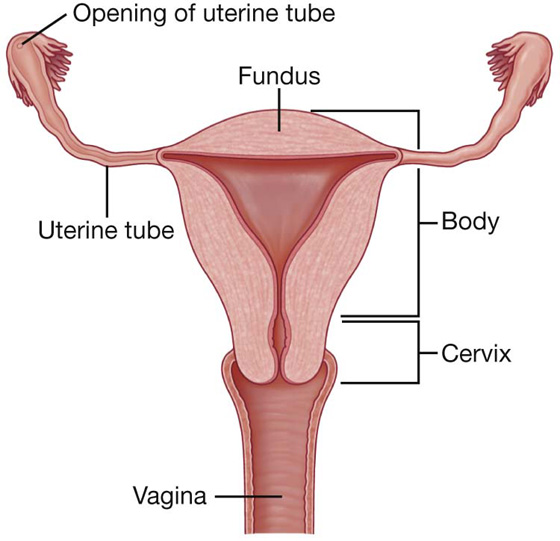

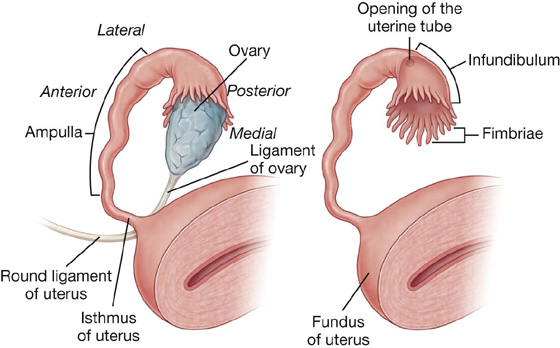

The uterus is a thick-walled muscular organ in the midline between the bladder and rectum (see Fig. 5.28). It consists of a body and a cervix, and inferiorly it joins the vagina (Fig. 5.29). Superiorly, uterine tubes project laterally from the uterus and open into the peritoneal cavity immediately adjacent to the ovaries (Fig. 5.29).

Fig. 5.29 Uterus. Anterior view. The anterior half of the uterus and vagina have been cut away.

The body of the uterus is flattened anteroposteriorly and, above the level of origin of the uterine tubes (Fig. 5.29), has a rounded superior end (fundus of uterus). The cavity of the body of the uterus is a narrow slit when viewed laterally, and is shaped like an inverted triangle when viewed anteriorly. Each of the superior corners of the cavity is continuous with the lumen of a uterine tube and the inferior corner is continuous with the central canal of the cervix.

Implantation of the blastocyst normally occurs in the body of the uterus. During pregnancy, the uterus dramatically expands superiorly into the abdominal cavity.

Clinical app

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. This is usually a complete excision of the body, fundus, and cervix of the uterus, though occasionally the cervix may be left in situ. In some instances the uterine (fallopian) tubes and the ovaries also are removed. This procedure is called a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy may be performed in patients who have reproductive malignancy, such as uterine, cervical, and ovarian cancers. Other indications include strong family history of reproductive disorders, endometriosis, and excessive bleeding. Occasionally the uterus may need to be removed postpartum because of excessive postpartum bleeding.

A hysterectomy is performed through a transverse suprapubic incision (Pfannenstiel’s incision). During the procedure, tremendous care is taken to identify the distal ureters and to ligate the nearby uterine arteries without damage to the ureters.

The uterine tubes extend from each side of the superior end of the body of the uterus to the lateral pelvic wall and are enclosed within the upper margins of the mesosalpinx portions of the broad ligaments. Because the ovaries are suspended from the posterior aspect of the broad ligaments, the uterine tubes pass superiorly over, and terminate laterally to, the ovaries.

Each uterine tube has an expanded trumpet-shaped end (the infundibulum), which curves around the superolateral pole of the related ovary (Fig. 5.30). The margin of the infundibulum is rimmed with small finger-like projections termed fimbriae. The lumen of the uterine tube opens into the peritoneal cavity at the narrowed end of the infundibulum. Medial to the infundibulum, the tube expands to form the ampulla and then narrows to form the isthmus, before joining with the body of the uterus (Fig. 5.30).

Fig. 5.30 Uterine tubes.

The fimbriated infundibulum facilitates the collection of ovulated eggs from the ovary. Fertilization normally occurs in the ampulla.

Clinical app

Tubal ligation

A simple and effective method of birth control is to surgically ligate (clip) the uterine tubes, preventing spermatozoa from reaching the ampulla.

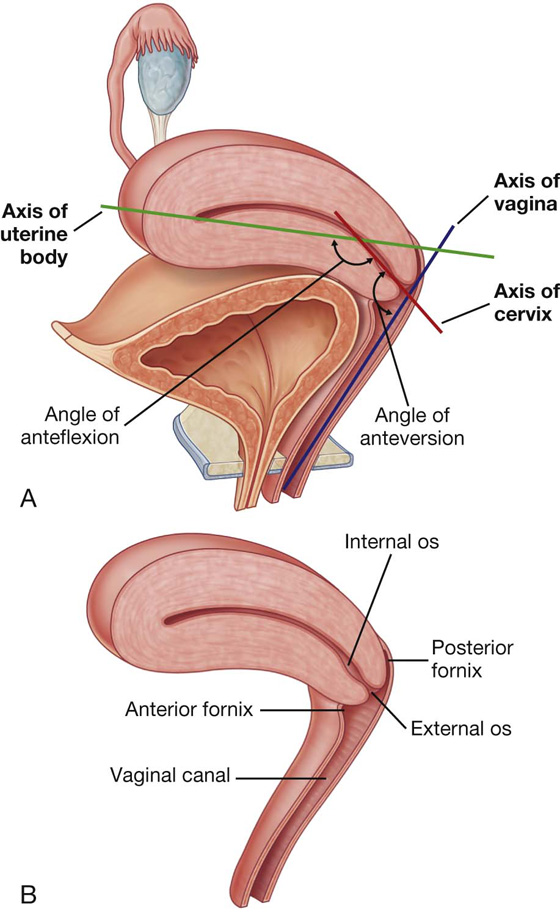

The cervix forms the inferior part of the uterus and is shaped like a short, broad cylinder with a narrow central channel. The body of the uterus normally arches forward (anteflexed on the cervix) over the superior surface of the emptied bladder (Fig. 5.31A). In addition, the cervix is angled forward (anteverted) on the vagina so that the inferior end of the cervix projects into the upper anterior aspect of the vagina (Figs. 5.31A, 5.32). Because the end of the cervix is dome shaped, it bulges into the vagina, and a gutter, or fornix, is formed around the margin of the cervix where it joins the vaginal wall (Fig. 5.31B). The tubular central canal of the cervix opens, below, as the external os, into the vaginal cavity and, above, as the internal os, into the uterine cavity (Fig. 5.31B).

Clinical app

Carcinoma of the cervix and uterus

Carcinoma of the cervix and uterus is a common disease in women. Diagnosis is by inspection, cytology (examination of the cervical cells), imaging, biopsy, and dilatation and curettage (D&C) of the uterus.

Carcinoma of the cervix and uterus may be treated by local resection, removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), and adjuvant chemotherapy. The tumor spreads via lymphatics to the internal and common iliac lymph nodes.

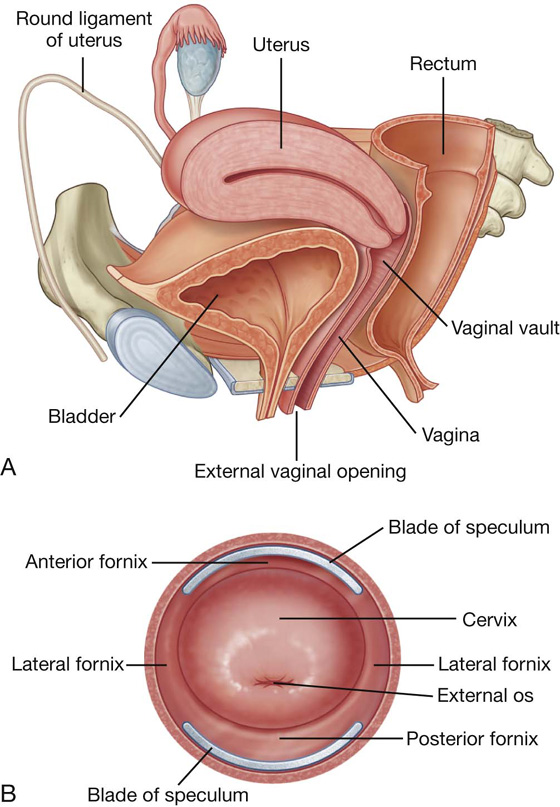

The vagina is the copulatory organ in women. It is a distensible fibromuscular tube that extends from the perineum through the pelvic floor and into the pelvic cavity (see Fig. 5.32A). The internal end of the canal is enlarged to form a region called the vaginal vault.

The anterior wall of the vagina is related to the base of the bladder and to the urethra; in fact, the urethra is embedded in, or fused to, the anterior vaginal wall (see Fig. 5.32A).

Posteriorly, the vagina is related principally to the rectum.

Inferiorly, the vagina opens into the vestibule of the perineum immediately posterior to the external opening of the urethra. From its external opening (the introitus), the vagina courses posterosuperiorly through the perineal membrane and into the pelvic cavity, where it is attached by its anterior wall to the circular margin of the cervix.

The vaginal fornix is the recess formed between the margin of the cervix and the vaginal wall. Based on position, the fornix is subdivided into a posterior fornix, an anterior fornix, and two lateral fornices (see Figs. 5.31B, 5.32B).

The vaginal canal is normally collapsed so that the anterior wall is in contact with the posterior wall. By using a speculum to open the vaginal canal, a physician can see the domed inferior end of the cervix, the vaginal fornices, and the external os of the cervical canal in a patient (see Fig. 5.31B).

During intercourse, semen is deposited in the vaginal vault. Spermatozoa make their way into the external os of the cervical canal, pass through the cervical canal into the uterine cavity, and then continue through the uterine cavity into the uterine tubes.

Fascia

Fascia in the pelvic cavity lines the pelvic walls, surrounds the bases of the pelvic viscera, and forms sheaths around blood vessels and nerves that course medially from the pelvic walls to reach the viscera in the midline. This pelvic fascia is a continuation of the extraperitoneal connective tissue layer found in the abdomen.

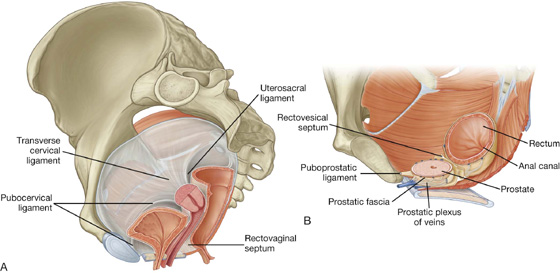

In women

In women, a rectovaginal septum separates the posterior surface of the vagina from the rectum (Fig. 5.33A). Condensations of fascia form ligaments that extend from the cervix to the anterior (pubocervical ligament), lateral (transverse cervical or cardinal ligament), and posterior (uterosacral ligament) pelvic walls. These ligaments, together with the perineal membrane, the levator ani muscles, and the perineal body, are thought to stabilize the uterus in the pelvic cavity. The most important of these ligaments are the transverse cervical or cardinal ligaments, which extend laterally from each side of the cervix and vaginal vault to the related pelvic wall.

Fig. 5.33 Pelvic fascia. A. In women. B. In men.

In men

In men, a condensation of fascia around the anterior and lateral region of the prostate (prostatic fascia) contains and surrounds the prostatic plexus of veins and is continuous posteriorly with the rectovesical septum, which separates the posterior surface of the prostate and base of the bladder from the rectum (Fig. 5.33B).

Peritoneum

The peritoneum of the pelvis is continuous at the pelvic inlet with the peritoneum of the abdomen. In the pelvis, the peritoneum drapes over the pelvic viscera in the midline, forming:

pouches between adjacent viscera, and

pouches between adjacent viscera, and

folds and ligaments between viscera and pelvic walls.

folds and ligaments between viscera and pelvic walls.

Anteriorly, median and medial umbilical folds of peritoneum cover the embryological remnants of the urachus and umbilical arteries, respectively (Fig. 5.34). These folds ascend out of the pelvis and onto the anterior abdominal wall. Posteriorly, peritoneum drapes over the anterior and lateral aspects of the upper third of the rectum, but only the anterior surface of the middle third of the rectum is covered by peritoneum; the lower third of the rectum is not covered at all.

Fig. 5.34 Peritoneum in the pelvis. A. In women. B. In men.

In women

In women, the uterus lies between the bladder and rectum, and the uterine tubes extend from the superior aspect of the uterus to the lateral pelvic walls (Fig. 5.34A). As a consequence, a shallow vesico-uterine pouch occurs anteriorly, between the bladder and uterus, and a deep recto-uterine pouch (pouch of Douglas) occurs posteriorly, between the uterus and rectum. In addition, a large fold of peritoneum (the broad ligament), with a uterine tube enclosed in its superior margin and an ovary attached posteriorly, is located on each side of the uterus and extends to the lateral pelvic walls.

In the midline, the peritoneum descends over the posterior surface of the uterus and cervix and onto the vaginal wall adjacent to the posterior vaginal fornix. It then reflects onto the anterior and lateral walls of the rectum. The deep pouch of peritoneum formed between the anterior surface of the rectum and posterior surfaces of the uterus, cervix, and vagina is the recto-uterine pouch. A sharp sickle-shaped ridge of peritoneum (recto-uterine fold) occurs on each side near the base of the recto-uterine pouch. The recto-uterine folds overlie the uterosacral ligaments, which are condensations of pelvic fascia that extend from the cervix to the posterolateral pelvic walls.

Broad ligament

The broad ligament is a sheetlike fold of peritoneum, oriented in the coronal plane that runs from the lateral pelvic wall to the uterus, and encloses the uterine tube in its superior margin and suspends the ovary from its posterior aspect (see Fig. 5.34). The uterine arteries cross the ureters at the base of the broad ligaments, and the ligament of the ovary and round ligament of the uterus are enclosed within the parts of the broad ligament related to the ovary and uterus, respectively. The broad ligament has three parts (see Fig. 5.34A):

the mesovarium, a posterior extension of the broad ligament, which attaches to the ovary.

the mesovarium, a posterior extension of the broad ligament, which attaches to the ovary.

The peritoneum of the mesovarium becomes firmly attached to the ovary as the surface epithelium of the ovary. The ovaries are positioned with their long axis in the vertical plane. The ovarian vessels, nerves, and lymphatics enter the superior pole of the ovary from a lateral position and are covered by another raised fold of peritoneum, which with the structures it contains forms the suspensory ligament of ovary (infundibulopelvic ligament) (see Fig. 5.34A).

The inferior pole of the ovary is attached to a fibromuscular band of tissue (the ligament of ovary), which courses medially in the margin of the mesovarium to the uterus and then continues anterolaterally as the round ligament of uterus (see Fig. 5.34). The round ligament of uterus passes over the pelvic inlet to reach the deep inguinal ring and then courses through the inguinal canal to end in connective tissue related to the labium majus in the perineum. Both the ligament of ovary and the round ligament of uterus are remnants of the gubernaculum, which attaches the gonad to the labioscrotal swellings in the embryo.

In men

In men, the visceral peritoneum drapes over the top of the bladder onto the superior poles of the seminal vesicles and then reflects onto the anterior and lateral surfaces of the rectum (see Fig. 5.34B). A rectovesical pouch occurs between the bladder and rectum.

Clinical app

The recto-uterine pouch

The recto-uterine pouch (pouch of Douglas) is an extremely important clinical region situated between the rectum and uterus. When the patient is in the supine position, the recto-uterine pouch is the lowest portion of the abdominopelvic cavity and is a site where infection and fluids typically collect. It is impossible to palpate this region transabdominally, but it can be examined by transvaginal and transrectal digital palpation. If an abscess is suspected, it may be drained by a needle placed through to the posterior fornix of the vagina or the anterior wall of the rectum.

Nerves

Somatic plexuses

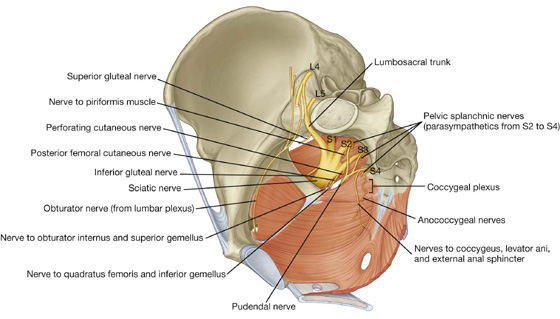

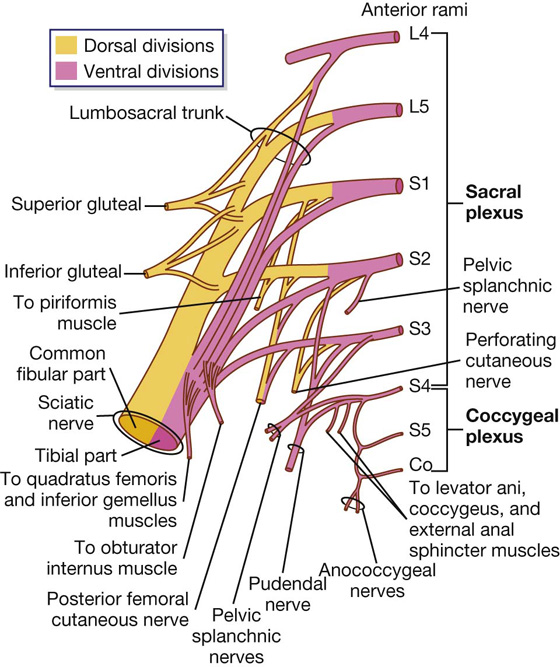

Sacral and coccygeal plexuses

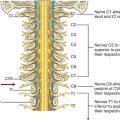

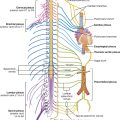

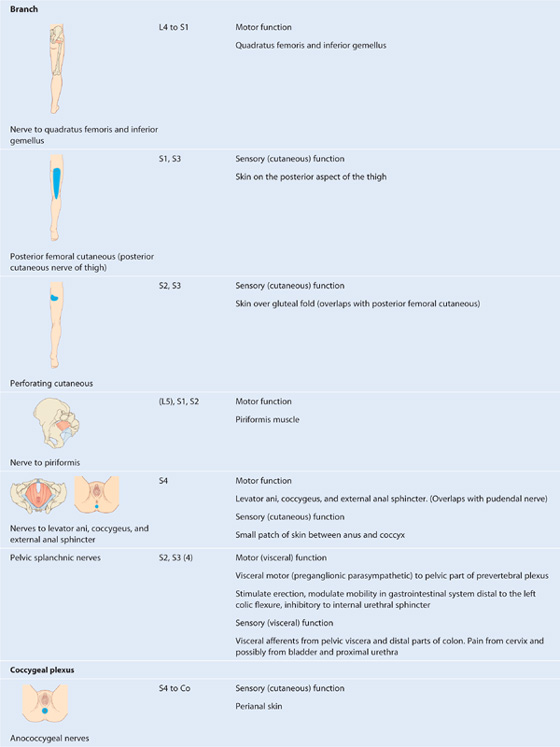

The sacral and coccygeal plexuses are situated on the posterolateral wall of the pelvic cavity and generally occur in the plane between the muscles and blood vessels. They are formed by the ventral rami of S1 to Co, with a significant contribution from L4 and L5, which enter the pelvis from the lumbar plexus (Figs. 5.35, 5.36). Nerves from these mainly somatic plexuses contribute to the innervation of the lower limb and muscles of the pelvis and perineum. Cutaneous branches supply skin over the medial side of the foot, the posterior aspect of the lower limb, and most of the perineum.

Fig. 5.35 Sacral and coccygeal plexuses.

Fig. 5.36 Components and branches of the sacral and coccygeal plexuses.

The sacral plexus on each side is formed by the anterior rami of S1 to S4, and the lumbosacral trunk (L4 and L5) (Fig. 5.36). The plexus is formed in relation to the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle, which is part of the posterolateral pelvic wall. Sacral contributions to the plexus pass out of the anterior sacral foramina and course laterally and inferiorly on the pelvic wall. The lumbosacral trunk, consisting of part of the anterior ramus of L4 and all of the anterior ramus of L5, courses vertically into the pelvic cavity from the abdomen by passing immediately anterior to the sacro-iliac joint.

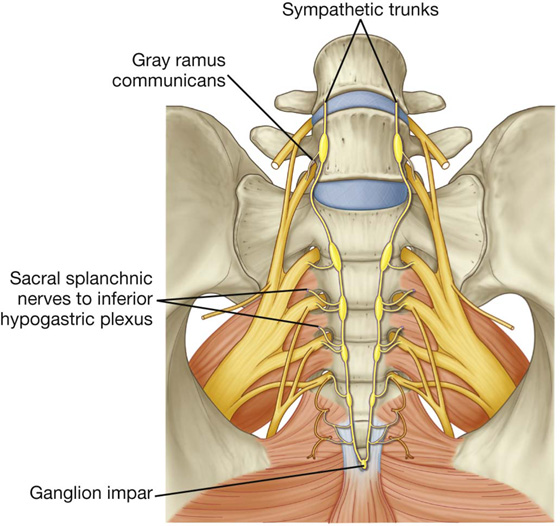

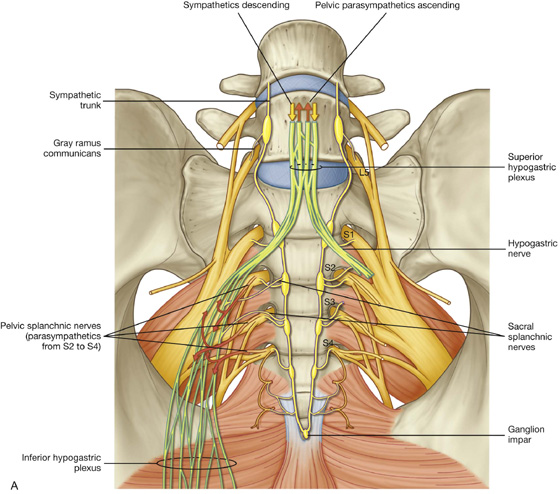

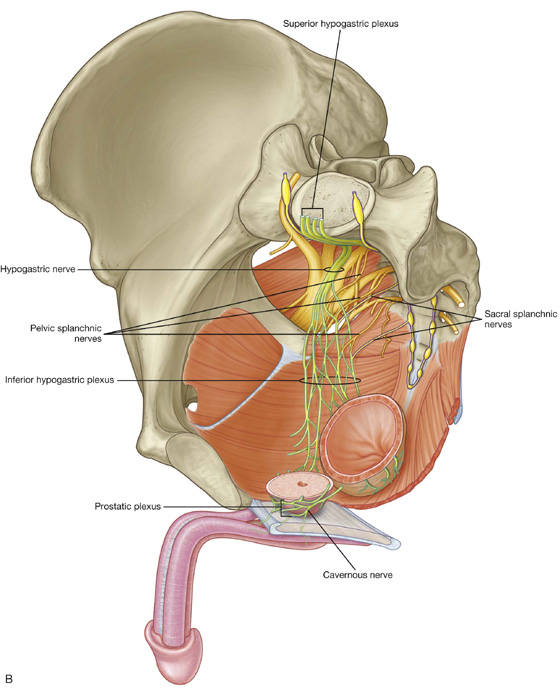

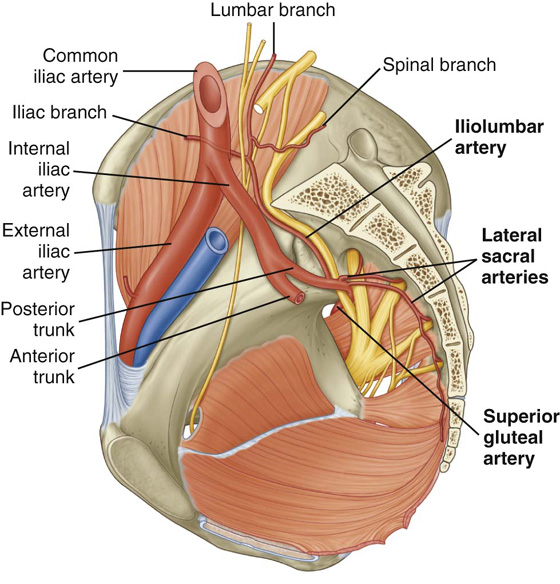

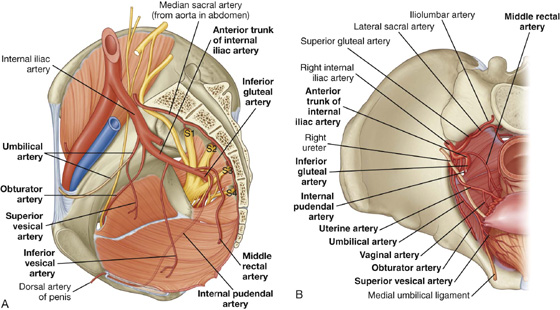

Gray rami communicantes from ganglia of the sympathetic trunk connect with each of the anterior rami and carry postganglionic sympathetic fibers destined for the periphery to the somatic nerves (Fig. 5.37). In addition, special visceral nerves (pelvic splanchnic nerves) originating from S2 to S4 deliver preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the pelvic part of the prevertebral plexus (Fig. 5.38, p. 237).

Fig. 5.37 Sympathetic trunks in the pelvis.

Fig. 5.38 Pelvic extensions of the prevertebral plexus. A. Anterior view.

Fig. 5.38 Pelvic extensions of the prevertebral plexus. B. Anteromedial view of right side of plexus.

Each anterior ramus has ventral and dorsal divisions that combine with similar divisions from other levels to form terminal nerves (Fig. 5.36). The anterior ramus of S4 has only a ventral division.

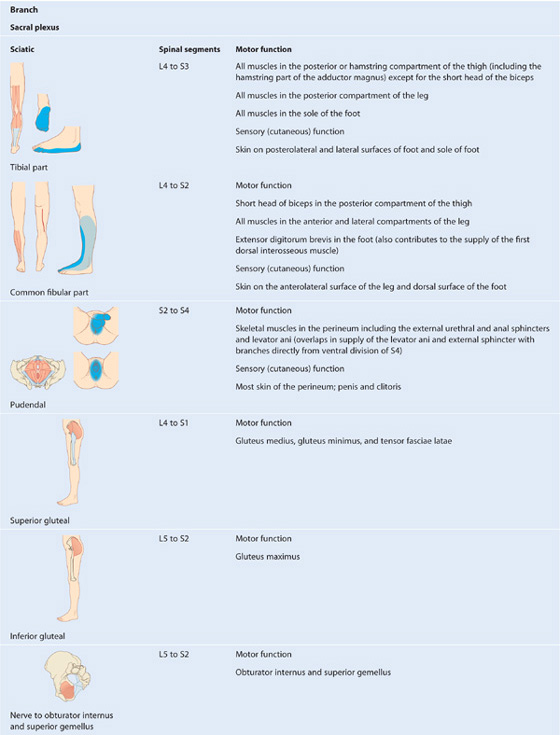

Branches of the sacral plexus include the sciatic nerve and gluteal nerves, which are major nerves of the lower limb, and the pudendal nerve, which is the nerve of the perineum (Table 5.4). Numerous smaller branches supply the pelvic wall, floor, and lower limb.

Table 5.4 Branches of the sacral and coccygeal plexuses (spinal segments in parentheses do not consistently participate)

Most nerves originating from the sacral plexus leave the pelvic cavity by passing through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to piriformis muscle, and enter the gluteal region of the lower limb. Other nerves leave the pelvic cavity using different routes; a few nerves do not leave the pelvic cavity and course directly into the muscles in the pelvic cavity. Finally, two nerves that leave the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen loop around the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament and pass medially through the lesser sciatic foramen to supply structures in the perineum and lateral pelvic wall.

Sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve of the body and carries contributions from L4 to S3 (Table 5.4, Figs. 5.35, 5.36). It:

innervates muscles in the posterior compartment of the thigh and muscles in the leg and foot; and

innervates muscles in the posterior compartment of the thigh and muscles in the leg and foot; and

carries sensory fibers from the skin of the foot and lateral leg.

carries sensory fibers from the skin of the foot and lateral leg.

Pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve forms anteriorly to the lower part of piriformis muscle from ventral divisions of S2 to S4 (Table 5.5; also see Figs. 5.35, 5.36). It:

Table 5.5 Muscles of the anal triangle

is accompanied throughout its course by the internal pudendal vessels; and

is accompanied throughout its course by the internal pudendal vessels; and

Clinical app

Pudendal block

Pudendal block anesthesia is performed to relieve the pain associated with childbirth. Although the use of this procedure is less common since the widespread adoption of edipural anesthesia, it provides an excellent option for women who have a contraindication to neuraxial anesthesia (e.g., spinal anatomy, low platelets, too close to delivery). Pudendal blocks are also used for certain types of chronic pelvic pain. The injection is usually given where the pudendal nerve crosses the lateral aspect of the sacrospinous ligament near its attachment to the ischial spine. During childbirth, a finger inserted into the vagina can palpate the ischial spine. The needle is passed transcutaneously to the medial aspect of the ischial spine and around the sacrospinous ligament. Infiltration is performed and the perineum is anesthetized.

Other branches of the sacral plexus (see Table 5.4). Other branches of the sacral plexus include:

sensory nerves to skin over the inferior gluteal region and posterior aspects of the thigh and upper leg (perforating cutaneous nerve and posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh) (see Figs. 5.35, 5.36).

sensory nerves to skin over the inferior gluteal region and posterior aspects of the thigh and upper leg (perforating cutaneous nerve and posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh) (see Figs. 5.35, 5.36).

The superior gluteal nerve leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen superior to the piriformis muscle and supplies muscles in the gluteal region.

The inferior gluteal nerve leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and supplies the gluteus maximus.

The nerve to the obturator internus and the associated superior gemellus muscle leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. Like the pudendal nerve, it passes around the ischial spine and through the lesser sciatic foramen to enter the perineum and supply the obturator internus muscle from the medial side of the muscle, inferior to the attachment of the levator ani muscle.

The nerve to the quadratus femoris muscle and the inferior gemellus muscle, and the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (posterior femoral cutaneous nerve) also leave the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and course to muscles and skin, respectively, in the lower limb.

Unlike most of the other nerves originating from the sacral plexus, which leave the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen either above or below the piriformis muscle, the perforating cutaneous nerve leaves the pelvic cavity by penetrating directly through the sacrotuberous ligament and then courses to skin over the inferior aspect of the buttocks.

The nerve to the piriformis and a number of small nerves to the levator ani and coccygeus muscles originate from the sacral plexus and pass directly into their target muscles without leaving the pelvic cavity.

The small coccygeal plexus has a minor contribution from S4 and is formed mainly by the anterior rami of S5 and Co, which originate inferiorly to the pelvic floor. They penetrate the coccygeus muscle to enter the pelvic cavity and join with the anterior ramus of S4 to form a single trunk, from which small anococcygeal nerves originate (see Table 5.4). These nerves penetrate the muscle and the overlying sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments and pass superficially to innervate skin in the anal triangle of the perineum.

Visceral plexuses

Paravertebral sympathetic chain

The paravertebral part of the visceral nervous system is represented in the pelvis by the inferior ends of the sympathetic trunks (Fig. 5.38A). Each trunk enters the pelvic cavity from the abdomen by passing over the ala of the sacrum medially to the lumbosacral trunks and posteriorly to the iliac vessels. The trunks course inferiorly along the anterior surface of the sacrum, where they are positioned medially to the anterior sacral foramina. Four ganglia occur along each trunk. Anteriorly to the coccyx, the two trunks join to form a single small terminal ganglion (the ganglion impar).

The principal function of the sympathetic trunks in the pelvis is to deliver postganglionic sympathetic fibers to the anterior rami of sacral nerves for distribution to the periphery, mainly to parts of the lower limb and perineum. This is accomplished by gray rami communicantes, which connect the trunks to the sacral anterior rami.

In addition to gray rami communicantes, other branches (the sacral splanchnic nerves) join and contribute to the pelvic part of the prevertebral plexus associated with innervating pelvic viscera.

Pelvic extensions of the prevertebral plexus

The pelvic parts of the prevertebral plexus carry sympathetic, parasympathetic, and visceral afferent fibers (see Fig. 5.38A). Pelvic parts of the plexus are associated with innervating pelvic viscera and erectile tissues of the perineum.

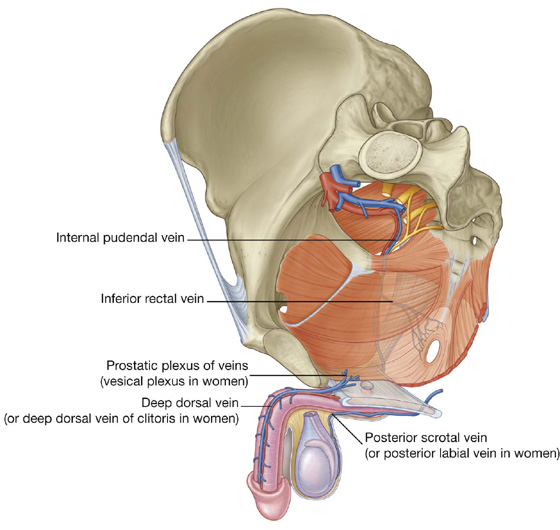

The prevertebral plexus enters the pelvis as two hypogastric nerves, one on each side, that cross the pelvic inlet medially to the internal iliac vessels. The hypogastric nerves are formed by the separation of the fibers in the superior hypogastric plexus into right and left bundles. The superior hypogastric plexus is situated anterior to vertebra LV between the promontory of the sacrum and the bifurcation of the aorta.