81 Pelvic Fractures

• Approximately 70% of patients with a traumatically disrupted pelvic ring will have a major associated injury.

• If a patient has displacement of 0.5 cm at any fracture site in the pelvis or has an “open book” pelvic fracture, massive transfusion may be needed.

• Blood loss from open book pelvic fractures and vertical shear injuries can be life-threatening.

• Emergency binding of the pelvis can help reduce pelvic volume and tamponade the bleeding. Binding the fractured pelvis too tightly should be avoided.

Epidemiology

Fractures of the bony pelvis account for 3% of all fractures; however, the overall mortality from pelvic ring injuries is 10% to 15%. Motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) involving cars or cars and pedestrians cause approximately 60% of pelvic fractures.1 Side-impact car collisions more commonly cause pelvic fractures than do head-on car collisions.2 Falls and motorcycle accidents are also significant causes of pelvic ring injuries.

Pathophysiology

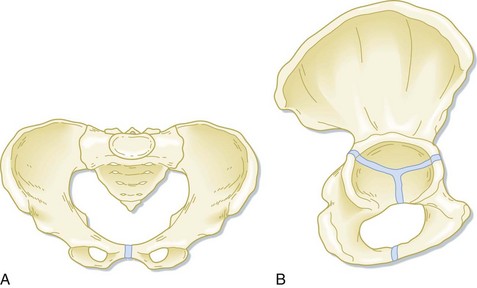

The pelvis provides support for upright mobility by connecting the spine to the lower extremities. When viewed as a whole, the pelvis contains a major ring and two inferior rings. The triangular sacrum and two innominate bones form the major pelvic ring (Fig. 81.1). The sacrum is a fusion of the five sacral vertebrae and distributes the weight of the upper part of the body to the innominate bones. The sacrum also conducts the sacral nerve roots to the pelvic organs. Each innominate bone is a fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubic bones. the intersection of the fusion forms the acetabulum, which articulates with the femur. Posteriorly, the innominate bones are anchored to the sacrum by the anterior and posterior iliac ligaments, two of the body’s strongest ligaments. The sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments attach the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity and the ischial spines bilaterally, thus further reinforcing the posterior arch of the pelvic ring.

Several classification schemes involving the direction of force applied to the pelvis, the bones injured, the degree of instability of the ring, and any associated injuries are used for pelvic ring disruptions. Fracture stability and increases in pelvic volume determine the magnitude of blood loss and potential mortality. See Box 81.1.

Tile Classification of Pelvic Fractures

The Tile classification adopted by the Orthopedic Trauma Association3 describes pelvic fractures by the degree of stability. The type and degree of stability predict outcome and associated injuries (see Box 81.1). Type A fractures are stable and include avulsion fractures and isolated fractures of an inferior pubic ramus, iliac wing, or distal sacrum. These fractures cause local pain but do involve the major pelvic ring.

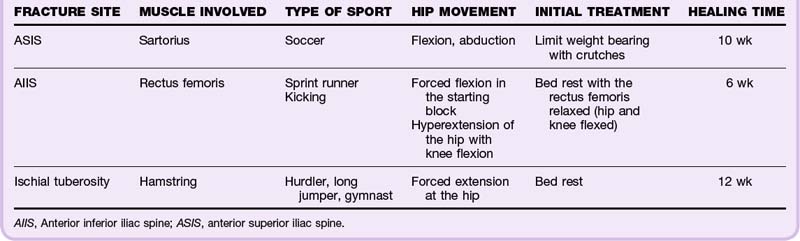

Avulsion fractures of the pelvis at muscle insertion sites are caused by forced contraction of the thigh muscles when moving the hip.4 The apophyses at the anterior superior iliac spine, the anterior inferior iliac spine, and the ischial tuberosity fuse between the ages of 16 and 25. Adolescent athletes involved in strenuous sports are vulnerable to these injuries. EPs should suspect these injuries based on the mechanism of injury (Table 81.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The classic findings in patients with a major pelvic ring disruption include a chief complaint of pelvic pain or pain with movement at the hips.5 However, nearly 70% of patients with disruption of the major pelvic ring have associated injuries, such as closed head trauma, blunt chest and abdominal trauma, and long-bone fractures,1 that may mask the symptoms of pelvic pain.

If no obvious fractures of the lower extremities are found, the femurs are rotated at the hips to assess for pain in the acetabula. Pain elicited by physical examination is 98% sensitive and 94% specific for predicting fracture of the posterior aspect of the pelvic ring.6

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

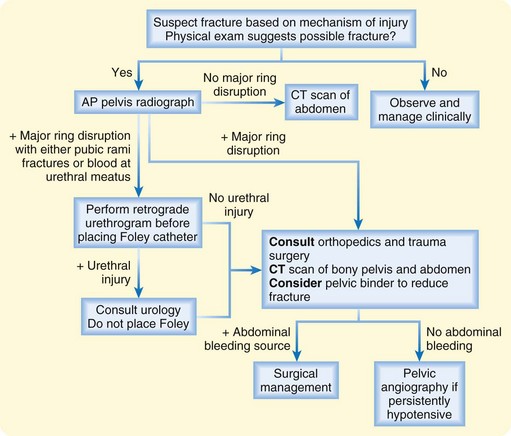

Figure 81.2 outlines a diagnostic and treatment approach to patients with suspected pelvic ring disruption.

Treatment

Pelvic fractures need to be reduced rapidly and fixated to prevent ongoing blood loss and promote healing. Reduction of a major pelvic ring disruption should increase interstitial pressure in the pelvis and at the bony surfaces of a fracture to tamponade any venous bleeding. Pelvic volume is also directly related to diastasis at the sites of ligamentous disruption, namely, the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints. A 1-cm widening of the pubic symphysis allows pelvic volume to expand 4.6%. A combined 8-cm widening of the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints would allow potentially 500 mL of blood to accumulate in the pelvis before the soft tissues even begin to tamponade the bleeding.7

Initially, the EP can reduce the fracture by applying a sheet circumferentially around the pelvis and tying it so that pelvic volume is reduced (Figs. 81.3 to 81.5). Commercial binders can be applied in the same manner. Such reduction works best for fractures with external rotation of one or both hemipelves, such as an open book pelvic fracture.8 The EP should be careful to not overcorrect the external rotation by binding the pelvis too tightly. Overcorrection could force sharp bony fragments into the pelvic vasculature and organs.

Bleeding can be life-threatening, and the posterior pelvic venous plexus accounts for more than 80% of hemorrhages.9 Early transfusion is indicated, particularly for patients with vertical shear or anteroposterior compression fractures. If a patient has 0.5-cm displacement at any fracture site in the pelvis or an open book pelvic fracture, massive transfusion will probably be needed. Patients who are persistently hypotensive despite fixation and transfusion may have an arterial bleeding source. Interventional radiology for embolization of the bleeding vessels can be lifesaving.9

For avulsion fractures, initial treatment is supportive, and physical activity is resumed slowly over a period of weeks to prevent repeated avulsion.5 After pain control has been achieved, these patients can be discharged home with follow-up by their primary care physician.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Mortality in patients with hemorrhagic shock from a pelvic fracture is about 50%.

Patients who undergo repair of major pelvic ring injuries may have chronic pelvic pain and typical operative complications, including infection and bleeding.

Concomitant head, chest, and abdominal injuries will contribute to the overall complication rate of pelvic fractures.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

RESCUE Pelvis Mnemonic for the Treatment of Patients with Pelvic Fractures

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Treatment

Imaging modalities selected, plain films, computed tomography, and other modalities

Consideration of binder application if open book injury

If transfer to a trauma facility is indicated, documentation of indications for transfer, efforts to stabilize, and neurovascular status at the time of transfer

Tips and Tricks

Pelvic Binder Application

To reduce the volume of an open book pelvic fracture, a bedsheet can be used in place of a commercial binder (see Fig. 81.4).

Fold the sheet lengthwise into thirds. Logroll the patient to place the sheet or binder posterior to the pelvis.

The superior edge of the sheet should be just inferior to both iliac crests. The umbilicus or natural waist should not be covered by the sheet. The inferior edge should not extend below the lesser trochanter.

The sheet should be knotted anterior to the patient with enough torque to reduce the symphysis diastasis to nearly normal: 1 to 3 cm for many patients.

Gonzalez RP, Fried PQ, Bukhalo M. The utility of clinical examination in screening for pelvic fractures in blunt trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:121–125.

Krieg JC, Mohr M, Ellis TJ, et al. Emergent stabilization of pelvic ring injuries by controlled circumferential compression: a clinical trial. J Trauma. 2005;59:659–664.

McCormick JP, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Clinical effectiveness of the physical examination in diagnosis of posterior pelvic ring injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:257–261.

Scopp JM, Moorman CT. Acute athletic trauma to the hip and pelvis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:555–563.

1 Gänsslen A, Pohlemann T, Paul C, et al. Epidemiology of pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27(Suppl 1):S-A13–S-A20.

2 Rowe SA, Sochor MS, Staples KS, et al. Pelvic ring fractures: implications of vehicle design, crash type, and occupant characteristics. Surgery. 2004;136:842–847.

3 Fracture and dislocation compendium. Orthopedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(Suppl 1):66–75.

4 Scopp JM, Moorman CT. Acute athletic trauma to the hip and pelvis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:555–563.

5 Gonzalez RP, Fried PQ, Bukhalo M. The utility of clinical examination in screening for pelvic fractures in blunt trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:121–125.

6 McCormick JP, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Clinical effectiveness of the physical examination in diagnosis of posterior pelvic ring injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:257–261.

7 Moss MC, Bircher MD. Volume changes within the true pelvis during disruption of the pelvic ring—where does the haemorrhage go? Injury. 1996;27(Suppl 1):S-A21–S-A23.

8 Krieg JC, Mohr M, Ellis TJ, et al. Emergent stabilization of pelvic ring injuries by controlled circumferential compression: a clinical trial. J Trauma. 2005;59:659–664.

9 White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009;40:1023–1030.