24 Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury

• Traumatic brain injury is a common pediatric problem, with mild injury being the predominant form.

• Abuse must be considered a mechanism of injury in preverbal children. Children younger than 2 years are at increased risk for skull fractures.

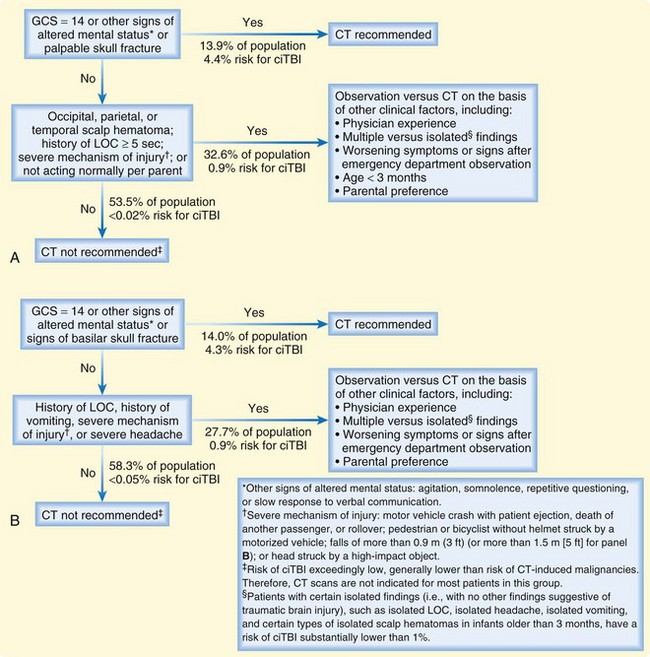

• Among pediatric patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14 or higher, a small number have significant intracranial injury. Guidelines can be used to identify those who are at very low risk for injury and minimize the use of computed tomography.

• Concussion is an important diagnosis to make in the emergency department setting. Appropriate discharge instructions (i.e., rest, restriction of activity, awareness of symptoms) may decrease morbidity.

Epidemiology

An estimated 615,000 traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) occur each year in patients younger than 19 years; this figure accounts for 26% of pediatric hospitalizations and 15% of all pediatric deaths.1 Children 0 to 4 years of age and older adolescents 15 to 19 years of age are most likely to sustain a TBI. Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), or concussion, represents the predominant form of acquired brain injury and accounts for 75% to 90% of all instances.2,3

Pathophysiology

Patients younger than 2 years are at higher risk for skull fractures, with the most common type being linear fractures. In infants, fractures may occur even after short falls (≤3 to 4 feet). The majority of fractures have an overlying hematoma or swelling; only 15% to 30% are associated with an intracranial injury.4 In general, linear skull fractures heal without incident. Rarely, in children with open fontanelles (<2 years old) and fractures with greater than 3-mm separation, a tear in the dura allows pulsation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or herniated meninges, which impedes fracture healing and extends the fracture over time.5 This may become apparent months to years after the initial injury and usually requires surgical correction. Depressed skull fractures with greater than 5 mm of depression generally require surgical correction. Basilar skull fractures have classic findings on physical examination (raccoon eyes, Battle sign, hemotympanum) and may be associated with cranial nerve palsies (facial palsy, nystagmus, diplopia, and facial numbness), CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea, and hearing loss.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

As with adults, the most predictive early indicator of outcome following head trauma is the initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score.6 The GCS has been modified for preverbal children (Table 24.1). A GCS score lower than 12 defines severe TBI. A GCS score of 13 to 15 represents mild to moderate TBI.

| Best eye response |

Medical Decision Making

Neuroimaging has been used to identify patients at risk for deterioration following TBI, but clinicians working with pediatric populations must balance the utility of neuroimaging with the risks associated with radiation and sedation (children may require sedation to obtain a computed tomography [CT] scan). Studies suggest that the theoretic risk for fatal brain tumors increases as age at time of intracranial imaging decreases, and even though complications of sedation are rare, many children experience prolonged recovery and delayed side effects.7 Studies have found that approximately 6% of children with minor head injury have abnormal findings on CT and, more important, that less than 1% require neurosurgical intervention.8 When compared with the adult population, pediatric patients are more likely to be seen in the ED following very mild injury, thus further lowering the pretest probability of significant intracranial injury.

Given this tendency, many studies have sought to identify criteria that would guide the use of neuroimaging in pediatric populations. A recent study by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) assessed 42,000 pediatric patients to develop a decision rule.9 For children 2 years or younger, they found that patients with abnormal mental status, non–frontal scalp hematoma, loss of consciousness, a severe mechanism of injury, and a palpable skull fracture and those who were not “acting normally” per parent could be accurately predicted to have significant intracranial injury. For patients older than 2 years, they found abnormal mental status, loss of consciousness, significant vomiting, severe mechanism of injury, clinical signs of basilar skull fracture, and severe headache predicted significant intracranial injury (Fig. 24.1). Use of these clinical guidelines would significantly reduce unnecessary intracranial imaging.

Observation is an alternative to neuroimaging in patients with mild injury. A retrospective Canadian study of approximately 17,000 pediatric patients older than 8 years found that delayed deterioration (>6 hours) occurred in no patients with a normal GCS score.10 Pediatric patients are often evaluated several hours after their injury; continued observation within the department or at home would be an acceptable alternative to emergency imaging in low-risk patients.

Admission and Discharge

The majority of patients with mTBI or concussion are reassured and discharged home. For these patients, appropriate diagnosis, patient education, and outpatient management may decrease recovery time, reduce the risk for secondary complications, and improve outcomes.11 Pediatric patients with normal neuroimaging findings but persistently abnormal GCS scores, severe vomiting, or unremitting headache should be admitted to the hospital for observation and hydration.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recently changed its recommendations for acute concussion management from the use of grading scales to use of the Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE) (see ACE and ACE-Care Plan, available at www.cdc.gov). The ACE is a paper evaluation form that was designed to provide a diagnostic framework for clinicians in the outpatient setting to define concussion and characterize the patient’s symptoms.12 Rather than focus on grading assessments of concussion severity, the ACE provides a standardized tool to aid in identifying mTBI in primary care settings. Unlike grading systems that provide set return-to-play decisions (e.g., those with grade 1 concussion may return to play in 15 minutes), the ACE offers an ACE-Care Plan, a set of best-practice discharge instructions that strongly recommend rest and endorse the “Stepwise Return to Play” (Box 24.1). The ACE-Care Plan also offers extensive information regarding return to school and work to minimize overexertion and improve recovery. The ACE and ACE-Care Plan represent a transition from passive management to active evaluation of concussion and intervention to decrease secondary injury.

Box 24.1

Stepwise Return to Play

1. Rest until asymptomatic (no signs or symptoms at rest or with exertion)

2. Light aerobic activity (e.g., walking, stationary bike)

3. Sport-specific activity (e.g., running in soccer, skating in hockey)

Adapted from McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport, held in Zurich, November 2008. J Clm Neurosci 2009;16:755-63.

Most patients with mTBI will recover within the first 7 to 10 days. In others, postconcussive syndrome will develop, a constellation of neurocognitive symptoms (including headaches, fatigue, sleep problems, changes in personality, photophobia, hyperacusis, dizziness, and deficits in short-term memory and problem solving) that may persist for days to weeks. Athletes who suffer multiple concussions are more likely to be plagued with postconcussive symptoms. School performance may be affected in these children, and some may need specific accommodation plans. Patients at high risk for complications related to mTBI (e.g., athletes, those with previous concussions or personal history of migraines) should be evaluated by a concussion specialist.13

Bazarian JJ, Blyth B, Cimpello L. Bench to bedside: evidence for brain injury after concussion—looking beyond the computed tomography scan. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:199–214.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. for the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Lancet. 2009;374:1160–1170.

McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 3rd International Conference on concussion in sport, held in Zurich, November 2008. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:755–763.

1 Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Thurman DJ. Incidence of mild and moderate brain injury in the United States, 1991. Brain Inj. 1996;10:47–54.

2 Collins MW, Iverson GL, Lovell MR, et al. On-field predictors of neuropsychological and symptom deficit following sports-related concussion. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:222–229.

3 Schultz M. Incidence and risk factors for concussion in high school athletes, north carolina, 1996-1999. Am J. Epidemiology. 2004;160:937–944.

4 Greenes DS, Schutzman SA. Infants with isolated skull fracture: what are their clinical characteristics, and do they require hospitalization? Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Sep;30:253–259.

5 Rinehart GC, Pittman T. Growing skull fractures: strategies for repair and reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 1998;9:65–72.

6 Holmes JF, Palchak MJ, MacFarlane T, et al. Performance of the pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale in children with blunt head trauma. Acad Emer Med. 2005;12:814–819.

7 Kim PK, Zhu X, Houseknecht E, et al. Effective radiation dose from radiologic studies in pediatric trauma patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:1557–1562.

8 Atabaki SM, Stiell IG, Bazarian JJ, et al. A clinical decision rule for cranial computed tomography in minor pediatric head trauma. Arch Ped Adolescent Med. 2008 May;162:439–445.

9 Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1160–1170.

10 Hamilton M, Mrazik M, Johnson DW. Incidence of delayed intracranial hemorrhage in children after uncomplicated minor head injuries. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e33–e39.

11 Ponsford J, Willmott C, Rothwell A, et al. Impact of early intervention on outcome after mild traumatic brain injury in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1297–1303.

12 Gioia GA, Collins M, Isquith PK. Improving identification and diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury with evidence: Psychometric support for the acute concussion evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008;23:230–242.

13 McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport, held in Zurich, November 2008. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:755–763.