Pediatric Orthopaedics

SECTION 1 BONE DYSPLASIAS (DWARFISM)

III. Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia

VI. Metaphyseal Chondrodysplasia

VII. Multiple Epiphyseal Dysplasia

VIII. Dysplasia Epiphysealis Hemimelica (Trevor Disease)

IX. Progressive Diaphyseal Dysplasia (Camurati-Engelmann Disease)

SECTION 2 CHROMOSOMAL AND TERATOLOGIC DISORDERS

SECTION 3 HEMATOPOIETIC DISORDERS

SECTION 4 METABOLIC DISEASE/ARTHRITIDES

III. Idiopathic Juvenile Osteoporosis

V. Infantile Cortical Hyperostosis (Caffey Disease)

SECTION 7 NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

II. Myelodysplasia (Spina Bifida)

III. Myopathies (Muscular Dystrophies)

IV. Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

VII. Anterior Horn Cell Disorders

VIII. Acute Idiopathic Postinfectious Polyneuropathy (Guillain-Barré Syndrome)

SECTION 8 CONGENITAL DISORDERS

II. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

III. Infantile Idiopathic Scoliosis

SECTION 10 UPPER EXTREMITY PROBLEMS

SECTION 11 LOWER EXTREMITY PROBLEMS: GENERAL

I. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

III. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease (Coxa Plana)

IV. Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

section 1 Bone Dysplasias (Dwarfism)

A Definition: Dysplasia means abnormal development.

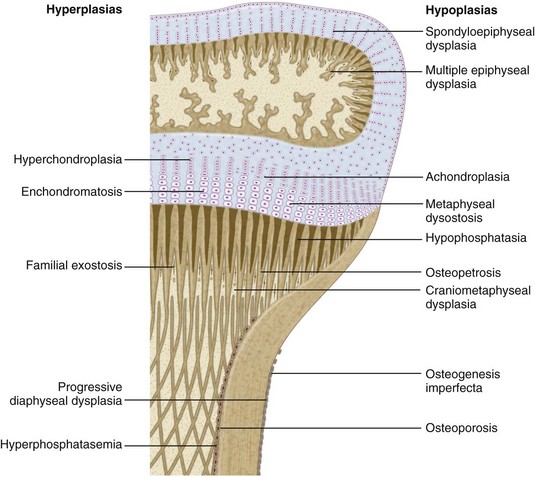

1. Shortening of the involved bones affects specific portions of the growing bone (Figure 3-1); hence the term dwarfism. Most forms of dwarfism are related to gene defects (single or multiple genes; Table 3-1).

Table 3-1![]()

Pediatric Congenital Disorders and Associated Genetic Defects

| Disorder | Genetic Defect |

| Achondroplasia | FGFR3 |

| Hypochondroplasia | FGFR3 |

| Thanatophoric dysplasia | FGFR3 |

| Pseudoachondroplasia | COMP |

| Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia type I | COMP |

| Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia type II | Collagen type IX |

| Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita | Collagen type II |

| Kniest syndrome | Collagen type II |

| Stickler syndrome (hereditary arthro-ophthalmopathy) | Collagen type II |

| Diastrophic dysplasia | Sulfate transporter gene |

| Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia | Collagen type X |

| Jansen metaphyseal chondrodysplasia | PTHRP |

| Craniosynostosis | FGFR2 |

| Cleidocranial dysplasia | CBFA1 |

| Hypophosphatemic rickets | PEX |

| Marfan syndrome | Fibrillin-1 |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta | Collagen type I |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | |

| Types I and II | Collagen type V |

| Type IV | Collagen type IV |

| Types VI and VII | Collagen type I |

| Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophies | Dystrophin |

| Limb-girdle dystrophies | Sarcoglycan and dystroglycan complex |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | PMP22 |

| Spinal muscular atrophy | Survival motor neuron protein |

| Myotonic dystrophy | Myotonin |

| Friedreich ataxia | Frataxin |

| Neurofibromatosis | Neurofibromin |

| McCune-Albright syndrome | cAMP |

B The term proportionate dwarfism implies a symmetric decrease in both trunk and limb length (e.g., as occurs with mucopolysaccharidoses).

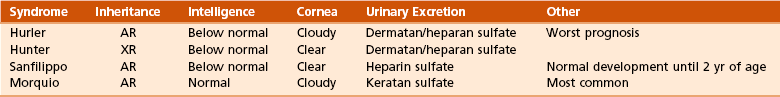

1. Achondroplasia is the most common form of disproportionate dwarfism.

2. Autosomal dominant condition; 80% of cases caused by a spontaneous mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3)

3. This disproportionate, short-limbed form of dwarfism is caused by abnormal endochondral bone formation that is more affected than appositional growth.

4. Anatomically, achondroplasia is categorized as a physeal dysplasia.

5. Caused by failure in the cartilaginous proliferative zone of the physis. Achondroplasia is a quantitative, not a qualitative, cartilage defect.

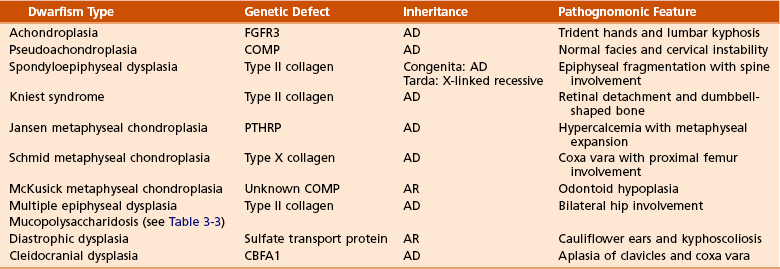

1. Normal trunk and short limbs (rhizomelic) with hypotonia

2. Frontal bossing, button noses, small nasal bridges, trident hands (inability to approximate extended middle and ring fingers) (Figure 3-2).

3. Thoracolumbar kyphosis (which usually resolves around the age at ambulation)

4. Lumbar stenosis (most likely to cause disability) and excessive lordosis (short pedicles with decreased interpedicular distances)

Neurologic symptoms are usually related to nerve root or spinal cord compression, which can occur at any level, including the foramen magnum (which may cause periods of apnea).

Neurologic symptoms are usually related to nerve root or spinal cord compression, which can occur at any level, including the foramen magnum (which may cause periods of apnea).

6. Normal intelligence but delayed motor milestones

7. Although sitting height may be normal, standing height is below the third percentile.

1. Lumbar stenosis: decompression and fusion of the spine for a developing neurologic deficit (usually in children older than age 10)

2. Foramen magnum stenosis: decompression

3. Progressive kyphosis: if fail bracing, anterior and posterior fusion are indicated for residual kyphosis greater than 60 degrees by age 5 years.

4. Genu varum: Tibial osteotomies or hemiepiphysiodesis

5. Limb lengthening through callodiastasis (lengthening through a metaphyseal corticotomy) have been well described, with a high rate of complications.

D Pseudoachondroplasia: This disorder is clinically similar to achondroplasia.

1. Genetics: The inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant with a defect on chromosome 19 within the cartilage oligometric matrix protein (COMP).

Orthopaedic manifestations include cervical instability; scoliosis with increased lumbar lordosis; significant lower extremity bowing; and hip, knee, and elbow flexion contractures with precocious osteoarthritis.

Orthopaedic manifestations include cervical instability; scoliosis with increased lumbar lordosis; significant lower extremity bowing; and hip, knee, and elbow flexion contractures with precocious osteoarthritis.

3. Radiographic findings: metaphyseal flaring and delayed epiphyseal ossification

III SPONDYLOEPIPHYSEAL DYSPLASIA

VI METAPHYSEAL CHONDRODYSPLASIA

1. Heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by metaphyseal changes of tubular bones with normal epiphyses

1. Jansen (rare): most severe form

Genetic defect is in parathyroid hormone–related peptide.

Genetic defect is in parathyroid hormone–related peptide.

Autosomal dominant inheritance; retardation, markedly short-limbed dwarfism with wide eyes, monkey-like stance, and hypercalcemia.

Autosomal dominant inheritance; retardation, markedly short-limbed dwarfism with wide eyes, monkey-like stance, and hypercalcemia.

Striking bulbous metaphyseal expansion of long bones is a distinctive radiographic finding.

Striking bulbous metaphyseal expansion of long bones is a distinctive radiographic finding.

Genetic defect is in type X collagen, transmitted by autosomal dominant inheritance; short-limbed dwarfism not diagnosed until patient is older, as a result of coxa vara and genu varum.

Genetic defect is in type X collagen, transmitted by autosomal dominant inheritance; short-limbed dwarfism not diagnosed until patient is older, as a result of coxa vara and genu varum.

Predominantly involves the proximal femur. Gait is often Trendelenburg, and patients have increased lumbar lordosis.

Predominantly involves the proximal femur. Gait is often Trendelenburg, and patients have increased lumbar lordosis.

Condition often confused with rickets, but laboratory test results are normal.

Condition often confused with rickets, but laboratory test results are normal.

Autosomal recessive inheritance; cartilage-hair dysplasia (hypoplasia of cartilage and small diameter of hair) is observed most commonly among the Amish population and in Finland.

Autosomal recessive inheritance; cartilage-hair dysplasia (hypoplasia of cartilage and small diameter of hair) is observed most commonly among the Amish population and in Finland.

Atlantoaxial instability is common (odontoid hypoplasia). Ankle deformity develops as a result of fibular overgrowth distally.

Atlantoaxial instability is common (odontoid hypoplasia). Ankle deformity develops as a result of fibular overgrowth distally.

Affected patients may have abnormal immunocompetence and have an increased risk for malignancies, intestinal malabsorption, and megacolon.

Affected patients may have abnormal immunocompetence and have an increased risk for malignancies, intestinal malabsorption, and megacolon.

VII MULTIPLE EPIPHYSEAL DYSPLASIA

1. Short-limbed, disproportionate dwarfism that often is not manifested until between the ages of 5 and 14. It must be differentiated from spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia. A mild form (Ribbing) and a more severe form (Fairbanks) exist.

1. MED is characterized by irregular, delayed ossification at multiple epiphyses (Figure 3-3).

2. Short, stunted metacarpals and metatarsals, irregular proximal femora, abnormal ossification (tibial “slant sign” and flattened femoral condyles, patella with double layer), valgus knees (early osteotomy should be considered), waddling gait, and early hip arthritis are common.

3. The proximal femoral involvement can be confused with Perthes disease.

VIII DYSPLASIA EPIPHYSEALIS HEMIMELICA (TREVOR DISEASE)

IX PROGRESSIVE DIAPHYSEAL DYSPLASIA (CAMURATI-ENGELMANN DISEASE)

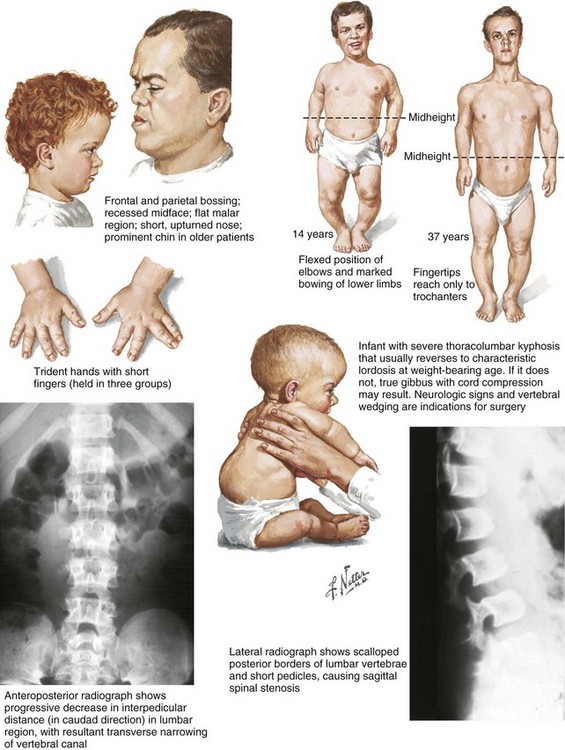

1. In contrast to the aforementioned conditions, these forms of dwarfism are easily differentiated on the basis of the presence of complex sugars in the urine.

2. The accumulation of mucopolysaccharides, as a result of a hydrolase enzyme deficiency, produces a proportionate dwarfism.

1. Morquio syndrome (autosomal recessive)

Most common form; manifests by ages 18 months to 2 years with waddling gait, genu valgum (“knock-knees”), thoracic kyphosis, cloudy corneas, and normal intelligence

Most common form; manifests by ages 18 months to 2 years with waddling gait, genu valgum (“knock-knees”), thoracic kyphosis, cloudy corneas, and normal intelligence

Urinary excretion of keratan sulfate

Urinary excretion of keratan sulfate

Bony changes include a thickening skull; wide ribs; anterior beaking of vertebrae; a wide, flat pelvis; coxa vara with unossified femoral heads; and bullet-shaped metacarpals.

Bony changes include a thickening skull; wide ribs; anterior beaking of vertebrae; a wide, flat pelvis; coxa vara with unossified femoral heads; and bullet-shaped metacarpals.

C1-C2 instability (caused by odontoid hypoplasia) can be seen with Morquio syndrome, manifesting with myelopathy and necessitating decompression and cervical fusion.

C1-C2 instability (caused by odontoid hypoplasia) can be seen with Morquio syndrome, manifesting with myelopathy and necessitating decompression and cervical fusion.

2. Hurler syndrome (autosomal recessive inheritance)

Urinary excretion of dermatan/heparan sulfate

Urinary excretion of dermatan/heparan sulfate

Bone marrow transplantation has increased the life span for patients with this disorder.

Bone marrow transplantation has increased the life span for patients with this disorder.

1. Autosomal recessive inheritance; severe, short-limbed dwarfism

2. Cleft palate (59% of cases)

3. Severe joint contractures (especially hip and knee)

XII CLEIDOCRANIAL DYSPLASIA (DYSOSTOSIS)

1. Autosomal dominant inheritance

2. Proportionate dwarfism that affects bones formed by intramembranous ossification (clavicles, cranium, pelvis)

section 2 Chromosomal and Teratologic Disorders

1. Usually characterized by ligamentous laxity, hypotonia, mental retardation, heart disease with atrial septal defect (50% of cases), endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism and diabetes), and premature aging

2. Orthopaedic problems include metatarsus primus varus, pes planus, spinal abnormalities (atlantoaxial instability [Figure 3-5], scoliosis [50% of cases], spondylolisthesis [6% of cases]), hip instability (open reduction with or without osteotomy is usually required), slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) (hypothyroidism should be sought), patellar dislocation, and symptomatic planovalgus feet.

3. Atlantoaxial instability may be subtle but commonly manifests as a loss or change in motor milestones.

1. Trisomy 21 is the most common chromosomal abnormality; its incidence increases with maternal age.

2. Chromosome 21 is the location of genes that encode for type VI collagen (COL6A1 and COL6A2).

1. Lower extremity radiographs are needed to evaluate for patella dislocations and genu valgum.

2. Anteroposterior and frog-leg pelvic views to evaluate for SCFE

3. Flexion-extension radiographs of the cervical spine to evaluate atlantoaxial instability

1. Screening for cervical spine instability:

2. Children with asymptomatic instability should avoid contact sports, diving, and gymnastics.

3. Children with symptomatic instability often require surgery, but the rate of wound healing problems and infection is high.

Cervical instability with neurologic symptoms: fusion with autologous bone graft and instrumentation, with consideration of halo immobilization

Cervical instability with neurologic symptoms: fusion with autologous bone graft and instrumentation, with consideration of halo immobilization

Scoliosis: bracing for 25- to 30-degree curves, surgery for 50- to 60-degree curves

Scoliosis: bracing for 25- to 30-degree curves, surgery for 50- to 60-degree curves

Hip: initially may be treated with closed reduction, but capsulorraphy, pelvis osteotomy, and femoral osteotomy may be required.

Hip: initially may be treated with closed reduction, but capsulorraphy, pelvis osteotomy, and femoral osteotomy may be required.

Patellar instability: if symptomatic, then lateral release, medial reefing, or bony realignment of the patellar tendon should be considered.

Patellar instability: if symptomatic, then lateral release, medial reefing, or bony realignment of the patellar tendon should be considered.

1. Affected patients are female and have short stature, lack of sexual development, webbed neck, and cubitus valgus.

2. Idiopathic scoliosis is common. Growth hormone therapy can exacerbate scoliosis.

3. Malignant hyperthermia is common with anesthetic use.

4. Must be differentiated from Noonan syndrome (same appearance except for normal gonadal development, mental retardation, and more severe scoliosis)

1. Progressive impairment and stereotaxic, abnormal hand movements (like those in autism)

2. Manifests in girls at 6 to 18 months of age

3. Loss of developmental milestones that is rapid and then stabilizes

VI BECKWITH-WIEDEMANN SYNDROME

1. Organomegaly, omphalocele, and a large tongue

2. Orthopaedic manifestations include hemihypertrophy with spastic cerebral palsy.

3. There is a predisposition to Wilms tumor (patient must be screened regularly with kidney ultrasonography).

VII TERATOGEN-INDUCED DISORDERS

A Fetal alcohol syndrome: Maternal alcoholism can cause growth disturbances, central nervous system dysfunction, dysmorphic facies, hip dislocation, cervical spine vertebral and upper extremity congenital fusions, congenital scoliosis, and myelodysplasia. Contractures respond to physical therapy.

B Maternal diabetes: This may lead to heart defects, sacral agenesis, and anencephaly. Careful management of pregnant diabetic women is essential.

C Other teratogens: These include drugs (e.g., aminopterin, phenytoin, thalidomide), trace metals, maternal conditions, infections, and intrauterine factors; they may also lead to orthopaedic manifestations in affected children.

section 3 Hematopoietic Disorders

2. Bone pain (Gaucher crisis), and bleeding abnormalities

1. Aberrant autosomal recessive, lysosomal storage disease characterized by accumulation of cerebroside in cells of the reticuloendothelial system. The cause is a deficiency of the enzyme β-glucocerebrosidase.

A Autosomal recessive disorder

B Caused by an accumulation of sphingomyelin in reticuloendothelial system cells

C Occurs commonly in Jews of eastern European descent

D Marrow expansion and cortical thinning are common in long bones; coxa valga is also seen.

1. Sickle cell disease (affects 1% of African Americans) is more severe but less common than sickle cell trait (8% prevalence).

2. Bone infarction is more common than acute osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell disease who present with acute musculoskeletal pain.

3. Salmonella infection is more commonly seen in children with sickle cell disease. Despite this tendency, Staphylococcus aureus infection is still the most common cause of osteomyelitis in affected patients.

1. Mutation in the β-globin gene, resulting in sickle hemoglobin (HbS) production. When the cell becomes deoxygenated, HbS molecules assemble into fibers that produce a sickle-shaped red blood cell.

2. Crises usually begin at ages 2 to 3 years, are caused by substance P, and may lead to characteristic bone infarctions.

A Similar to sickle cell anemia in manifestation

B Most commonly observed in people of Mediterranean descent

C Common symptoms include bone pain and leg ulceration

D Radiographic findings: long-bone thinning, metaphyseal expansion, osteopenia, and premature physeal closure

1. Hemarthrosis manifests with painful swelling and decreased range of motion (ROM) of affected joints.

2. The knee is the joint most commonly affected.

3. Deep intramuscular bleeding is also common and can lead to the formation of a pseudotumor (blood cyst), which can occur in soft tissue or bone.

1. X-linked recessive disorder with decreased amounts of factor VIII (hemophilia A), abnormal factor VIII with platelet dysfunction (von Willebrand disease), or decreased amounts of factor IX (hemophilia B, Leyden, or Christmas disease)

2. Can be mild (5% to 25% of normal amounts of factor present), moderate (1% to 5% available), or severe (<1% present)

1. Squaring of the patellae and condyles, epiphyseal overgrowth with leg-length discrepancy

2. Generalized osteopenia with resulting fractures

3. Cartilage atrophy, resulting from enzymatic matrix degeneration and chondrocyte death, is frequent.

1. Acute treatment of hemarthrosis is crucial and should begin immediately with administration of factor VIII or factor IX. Administration should continue for 3 to 7 days after cessation of bleeding and should be followed by physical therapy.

2. Home transfusion therapy has reduced the severity of the arthropathy with the advantage of immediate treatment when bleeding occurs.

3. Aspiration of a hemarthrosis is controversial.

Indicated for hemarthroses that recur despite optimal medical management

Indicated for hemarthroses that recur despite optimal medical management

Arthroscopy has better results with motion and duration of hospitalization than does open synovectomy.

Arthroscopy has better results with motion and duration of hospitalization than does open synovectomy.

Radiation synovectomy: useful in patients with antibody inhibitors and poor medical management

Radiation synovectomy: useful in patients with antibody inhibitors and poor medical management

5. Factor VIII levels should be increased for prophylaxis in the following situations: vigorous physical therapy (20% of patients), treatment of hematoma (30%), acute hemarthrosis or soft tissue surgery (>50%), and skeletal surgery (approaching 100% preoperatively and maintained at >50% for 10 days postoperatively).

6. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody inhibitors are present in 4% to 20% of hemophiliac patients; their presence is a relative contraindication to surgery.

7. Because of the amount of blood component therapy needed to treat this disorder, a large percentage of older hemophiliac patients are seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

1. The most common malignancy of childhood. Acute lymphocytic leukemia represents 80% of cases of leukemia.

2. Incidence peaks at 4 years of age.

3. One fourth to one third of affected children have musculoskeletal complaints (back, pelvic, leg pains).

section 4 Metabolic Disease/Arthritides*

1. Deficiency of calcium (and sometimes phosphorus), affecting mineralization at the epiphyses of long bones

2. Histologic findings: Widened osteoid seams and “Swiss cheese” trabeculae are characteristic in bone.

3. Growth plate abnormalities include enlarged and distorted maturation zone (zone of hypertrophy) and a poorly defined zone of provisional calcification.

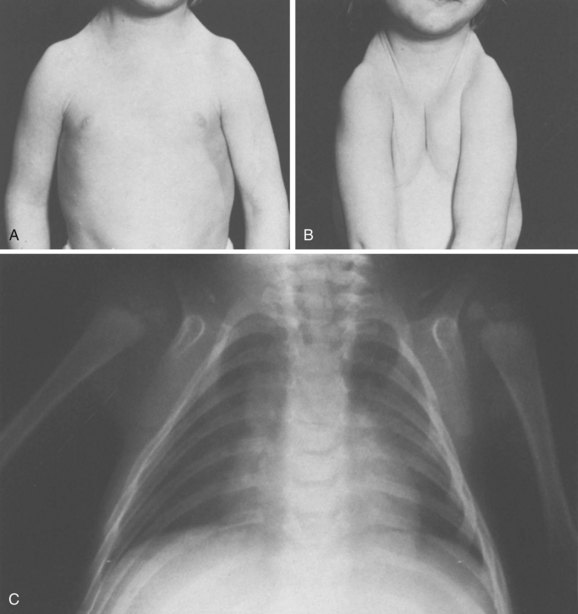

1. Bone fragility (brittle “wormian” bone), short stature

3. Tooth defects (dentinogenesis imperfecta)

5. Blue sclerae in types I and II

7. Basilar invagination is common in more severe clinical phenotypes.

1. Defect in type I collagen (COL1A2 gene) that causes abnormal cross-linking and leads to decreased collagen secretion

2. Histologic findings: increased diameters of haversian canals and osteocyte lacunae, increased numbers of cells, and replicated cement lines, which result in the thin cortices seen on radiographs

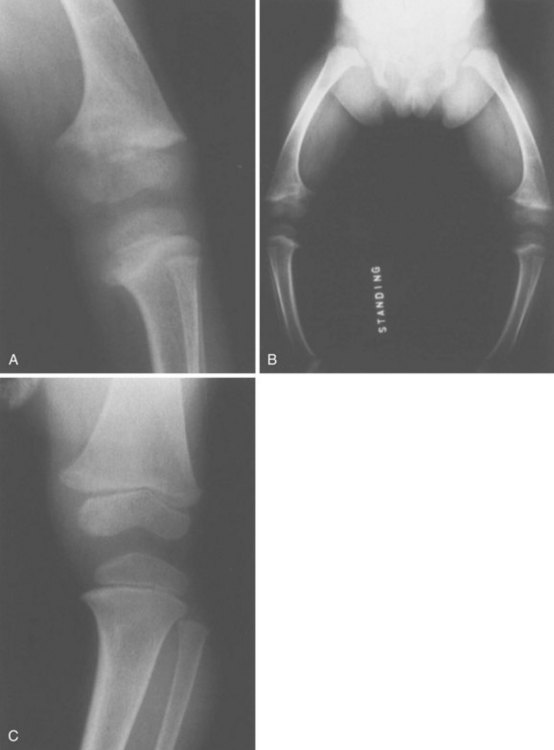

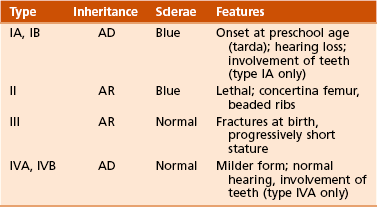

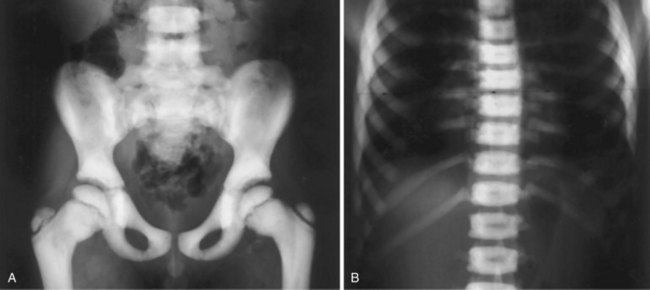

Four types have been identified (Sillence, 1981), although the disorder is probably best considered as a continuum with different inheritance patterns and severity (Table 3-4).

Four types have been identified (Sillence, 1981), although the disorder is probably best considered as a continuum with different inheritance patterns and severity (Table 3-4).

1. Fracture management and long-term rehabilitation

2. Bracing of extremities early to prevent deformity and minimize fractures

3. Sofield osteotomies—“shish kebab” multiple long-bone osteotomies with either fixed-length Rush rods or telescoping (Bailey-Dubow or Fassier-Duval) intramedullary rods—are sometimes required for progressive bowing of long bones.

4. Fractures in children younger than 2 years are treated similarly to those in children without osteogenesis imperfecta. After age 2, telescoping intramedullary rods can be considered.

5. Bisphosphonates have been shown to decrease the number of fractures in these patients.

6. Scoliosis is common, and bracing is ineffective treatment. Surgery is necessary for scoliosis deformities exceeding 50 degrees, and a large blood loss is to be expected.

III IDIOPATHIC JUVENILE OSTEOPOROSIS

2. Loss of the medullary canal can cause anemias and encroachment on the optic and oculomotor nerves, which in turn causes blindness.

1. Failure of osteoclastic resorption, probably secondary to a defect in the thymus, leading to dense bone (so-called “marble” bone)

2. The mild form is autosomal dominant; the “malignant” form is autosomal recessive.

V INFANTILE CORTICAL HYPEROSTOSIS (CAFFEY DISEASE)

1. Soft tissue swelling and bony cortical thickening (especially the jaw and ulna) that follow a febrile illness in infants 0 to 9 months old.

2. This disorder may be differentiated from trauma (and child abuse) on the basis of single-bone involvement.

3. Infection, scurvy, tumor, and progressive diaphyseal dysplasia may be included in the differential diagnosis.

1. Arachnodactyly (long, slender fingers; “peeking thumb sign”), pectus deformities, scoliosis (50% of cases), acetabular protrusio (15% to 25%), cardiac abnormalities (aortic dilation), and ocular abnormalities (superior lens dislocation in 60%)

1. Joint laxity is treated conservatively.

2. Bracing for scoliosis is ineffective.

3. Curves may necessitate anterior and posterior fusion.

4. Echocardiographic and cardiologic evaluation are required before surgery.

5. Acetabular protrusio should be observed unless the patient has severe symptoms.

1. Osteoporosis, a marfanoid-like habitus (but with stiffening joints)

3. Differentiated from Marfan syndrome on the basis of the direction of lens dislocation and the presence of osteoporosis in homocystinuria

4. Central nervous system effects, including mental retardation, are common in this disorder.

1. Autosomal recessive inborn error of methionine metabolism (decreased enzyme cystathionine β-synthase). Accumulation of the intermediate metabolite homocysteine in the production of the amino acid cysteine.

2. The diagnosis is made by demonstrating increased homocysteine in urine (cyanide-nitroprusside test).

IX JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

A Includes both juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile chronic arthritis

1. Persistent noninfectious arthritis lasting 6 weeks to 3 months and diagnosed after other possible causes have been ruled out

2. Affects girls more than boys and typically manifests before age 4 years

3. Commonly involves the knee, wrist (flexed and ulnar deviated) and hand (fingers extended, swollen, radially deviated)

4. To confirm the diagnosis, one of the following must be present: rash, presence of rheumatoid factor, iridocyclitis, cervical spine involvement, pericarditis, tenosynovitis, intermittent fever, or morning stiffness.

5. In 50% of affected patients, symptoms resolve without sequelae; 25% of patients are slightly disabled, and 20% to 25% have crippling arthritis, blindness, or both.

1. Cervical spine involvement can lead to kyphosis, facet ankylosis, and atlantoaxial subluxation.

2. Lower extremity problems include flexion contractures (hip and knee flexed, ankle dorsiflexed), subluxation, and other deformities (hip protrusio, valgus knees, equinovarus feet).

1. Medical therapy involves less high-dose steroids and salicylates and more specific immunomodulating drugs (infliximab).

2. Surgical interventions include joint injections and (rarely) synovectomy (for chronic swelling refractory to medical management). Arthrodesis and arthroplasty may be required for severe juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

3. Slit-lamp examination is required twice yearly, as progressive iridocyclitis can lead to rapid loss of vision if left untreated.

1. Typically affects adolescent boys with asymmetric, lower extremity, large-joint arthritis; heel pain; and sometimes eye symptoms

2. Hip and back pain (cardinal symptoms) may develop later.

3. Limitation of chest wall expansion is a more specific finding than is a positive HLA-B27 test result.

1. The HLA-B27 test yields positive results in 90% to 95% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis or Reiter syndrome, but the result is also positive in 4% to 8% of all white Americans; thus, its usefulness as a screening tool is limited.

section 5 Birth Injuries

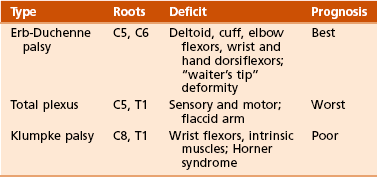

1. In 2 per 1000 births, an injury is still associated with stretching or contusion of the brachial plexus.

2. Typically present with internal rotation contracture of the shoulder and with elbow and wrist flexion contractures.

Progressive glenoid dysplasia occurs in 70% of children with significant internal rotation contracture.

Progressive glenoid dysplasia occurs in 70% of children with significant internal rotation contracture.

3. Hand function is variable, according to level of brachial plexus deformity.

1. Investigations have focused on the position of the humeral head within the glenoid.

2. Axillary lateral view of the shoulder should be obtained to evaluate position of humeral head.

3. Consider computed tomographic (CT) scanning instead of MRI of the shoulder if surgical reconstruction is planned.

1. The key to the success of therapy is maintaining passive ROM and awaiting return of motor function (up to 18 months).

2. More than 90% of cases eventually resolve without intervention.

Lack of biceps function 6 months after injury and the presence of Horner syndrome carry a poor prognosis.

Lack of biceps function 6 months after injury and the presence of Horner syndrome carry a poor prognosis.

3. Options include releasing contractures (Fairbanks), latissimus and teres major transfer to the shoulder external rotators (L’Episcopo), tendon transfers for elbow flexion (Clark pectoral transfer and Steindler flexorplasty), proximal humerus rotational osteotomy (Wickstrom), and microsurgical nerve grafting.

4. Release of the subscapularis tendon for internal rotation contracture, if performed by age 2 years, may result in improved active external rotation of the shoulder, with muscle transfer to assist in active external rotation.

II CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS

1. It is associated with other “molding disorders,” such as hip dysplasia and metatarsus adductus (up to 20% association with hip dysplasia).

2. Fibrosis of the muscle and a palpable mass are noted within the first 4 weeks of life.

3. This is a diagnosis of exclusion, inasmuch as other causes for the torticollis must be evaluated:

1. A congenital deformity resulting from contracture of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, perhaps from an intrauterine compartment syndrome involving this muscle.

1. Anteroposterior and lateral views of the cervical spine are needed.

2. Ultrasonography has been shown to differentiate between mild fibrosis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and severe fibrosis.

1. Most patients (90%) respond to passive stretching within the first year of life.

Rotate the infant’s chin to the ipsilateral shoulder while simultaneously tilting the head toward the contralateral shoulder.

Rotate the infant’s chin to the ipsilateral shoulder while simultaneously tilting the head toward the contralateral shoulder.

A physical therapist can assist in ensuring that the infant makes progress,

A physical therapist can assist in ensuring that the infant makes progress,

Ultrasound demonstration of severe fibrosis is associated with failure of nonoperative management.

Ultrasound demonstration of severe fibrosis is associated with failure of nonoperative management.

2. Surgery (Z-plasty of the sternocleidomastoid muscle) may be required if torticollis persists beyond the first year.

III CONGENITAL PSEUDARTHROSIS OF THE CLAVICLE

1. Surgery (open reduction, internal fixation with bone grafting) is indicated for unacceptable cosmetic deformities or with significant functional symptoms (mobility of the fragments and winging of the scapula) at ages 3 to 6 years.

2. Successful union is predictable (in contrast to congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia).

section 6 Cerebral Palsy

A This nonprogressive neuromuscular disorder. with onset before age 2 years, results from injury to the immature brain.

B The cause is usually not identifiable but can include prematurity (most common), prenatal intrauterine factors, perinatal infections (toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex), anoxic injuries, and meningitis.

C This upper motor neuron disease results in a mixture of muscle weakness and spasticity.

D Initially, the abnormal muscle forces cause dynamic deformity at joints.

1. Persistent spasticity can lead to contractures, bony deformity, and ultimately joint subluxation/dislocation.

E MRI of the brain commonly reveals periventricular leukomalacia.

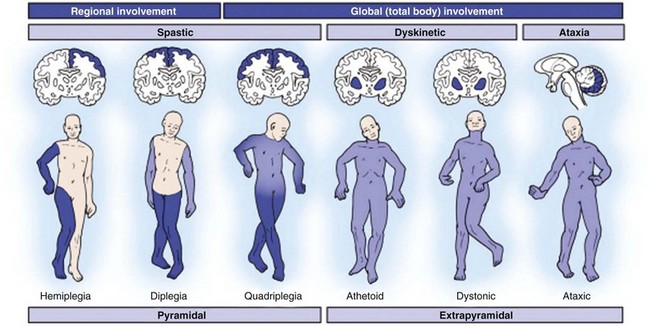

A Cerebral palsy can be classified on the basis of physiology (according to the movement disorder), anatomy (according to geographic distribution), or function.

B Physiologic classification (Figure 3-8):

Increased muscle tone and hyperreflexia with slow, restricted movements because of simultaneous contraction of agonist and antagonist

Increased muscle tone and hyperreflexia with slow, restricted movements because of simultaneous contraction of agonist and antagonist

Most common and is most amenable to improvement of musculoskeletal function by operative intervention

Most common and is most amenable to improvement of musculoskeletal function by operative intervention

C Anatomic classification (see Figure 3-8):

Involves the upper and lower extremities on the same side, usually with spasticity

Involves the upper and lower extremities on the same side, usually with spasticity

“Handedness” often develops early

“Handedness” often develops early

All children with hemiplegia are eventually able to walk, regardless of treatment.

All children with hemiplegia are eventually able to walk, regardless of treatment.

1. Intramuscular botulinum A toxin can temporarily decrease dynamic spasticity.

2. The mechanism of action of botulinum toxin is a presynaptic blockade at the neuromuscular junction.

3. The effectiveness of botulinum toxin is limited to 6 months; therefore, it is not a permanent cure for spasticity.

4. It is used to maintain joint motion during rapid growth when a child is too young for surgery.

1. Selective dorsal root rhizotomy is a neurosurgical procedure designed to decrease lower extremity spasticity.

2. The procedure includes resection of dorsal rootlets that do not exhibit a myographic or clinical response to stimulation.

3. It is performed primarily in ambulatory patients with spastic diplegia to help reduce spasticity and complement orthopaedic management.

4. It requires multilevel laminoplasty, which may lead to late spinal instability and deformity.

1. Findings are usually the impetus for the orthopaedic consultation.

2. In many hemiplegic patients, toe walking is the only manifestation.

3. Three-dimensional computerized gait analysis with dynamic electromyography and force-plate studies have allowed a more scientific approach to preoperative decision making and postoperative analysis of the results of surgery for cerebral palsy.

1. Lengthening of continuously active muscles and transfer of muscles out of phase are often helpful. Surgeries should usually be done at multiple levels to best correct the problem. In general, surgery is performed at ages 4 to 5 years. A few generalized guidelines are given in Table 3-6.

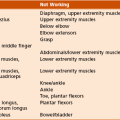

Table 3-6![]()

Surgical Options for Gait Disorders

| Problem | Diagnostic Findings | Surgical Option |

| Hip flexion | Positive result of Thomas test | Psoas tenotomy or recession |

| Spastic hip | Decreased abduction, uncovered femoral head | Adductor release, osteotomy (late) |

| Hip adduction | Scissoring gait | Adductor release |

| Femoral anteversion | Prone internal rotation increased | Osteotomy, VDRO, hamstring lengthening |

| Knee flexion | Increased popliteal angle | Hamstring lengthening |

| Knee hypertension | Recurvatum | Rectus femoris lengthening |

| Stiff-leg gait | Electromyographic study of hamstring and quadriceps; continuous passive knee flexion decreased with hip extension | Distal rectus transfer to hamstrings |

| Talipes equinus | Toe walking | Achilles tendon lengthening |

| Talipes varus | Appearance in standing position | Split–anterior or split–posterior tibialis transfer (on the basis of EMG findings) |

| Talipes valgus | Appearance in standing position | Peroneal lengthening, Grice subtalar fusion, calcaneal lengthening osteotomy |

| Hallux valgus | Appearance on examination and radiographs | Osteotomy, metatarsophalangeal fusion |

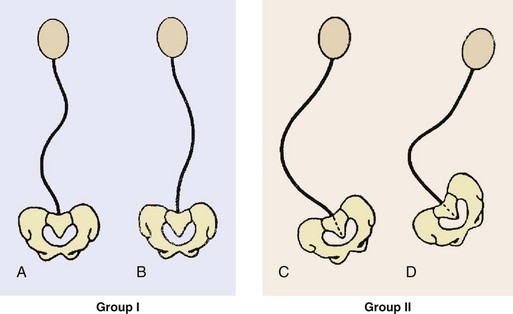

1. These disorders most commonly involve scoliosis, which can be severe, making proper wheelchair sitting difficult.

2. The risk for scoliosis is highest in children with total body involvement (spastic quadriplegic).

3. Surgical indications include curves greater than 45 to 50 degrees, worsening pelvic obliquity, or wheelchair seating problems.

1. Treatment is tailored to the needs of the patient and must involve all caregivers.

2. Small curves with no loss of function or large curves in severely involved patients may necessitate only observation.

3. Group I curves in ambulatory patients are treated as idiopathic scoliosis with posterior fusion and instrumentation. Group I curves in sitting patients and group II curves may necessitate posterior fusion with segmental posterior instrumentation from the upper thoracic spine to the pelvis (Luque-Galveston technique), with or without anterior fusion.

4. Kyphosis is also common and may necessitate fusion and instrumentation.

5. It is important to assess nutritional status (albumin < 3.5 g/dL and white blood cell [WBC] count < 1500/µL) preoperatively and to consider gastrostomy tube placement before spinal surgery if indicated.

VII HIP SUBLUXATION AND DISLOCATION

1. In many children, pathologic processes of the hip are asymptomatic.

2. Caregivers may describe a pain response.

3. Difficulty with abduction for peroneal care is the most common problem.

1. Initial treatment is with a soft tissue release (adductor/psoas) plus abduction bracing.

2. Later, hip subluxation or dislocation may necessitate femoral or acetabular osteotomies (Dega), or both, to maintain hip stability.

3. The goal is to keep the hip reduced.

4. This entity is characterized by four stages:

Hip at risk: abduction of less than 45 degrees, with partial uncovering of the femoral head on radiographs. This situation is the only exception to the general rule of avoiding surgery in patients with cerebral palsy during the first 3 years of life.

Hip at risk: abduction of less than 45 degrees, with partial uncovering of the femoral head on radiographs. This situation is the only exception to the general rule of avoiding surgery in patients with cerebral palsy during the first 3 years of life.

Hip subluxation: best treated with adductor tenotomy in children with abduction of less than 20 degrees, sometimes with psoas release or recession.

Hip subluxation: best treated with adductor tenotomy in children with abduction of less than 20 degrees, sometimes with psoas release or recession.

Femoral or pelvic osteotomies may be considered in cases of femoral coxa valga and acetabular dysplasia, which is usually lateral and posterior.

Femoral or pelvic osteotomies may be considered in cases of femoral coxa valga and acetabular dysplasia, which is usually lateral and posterior.

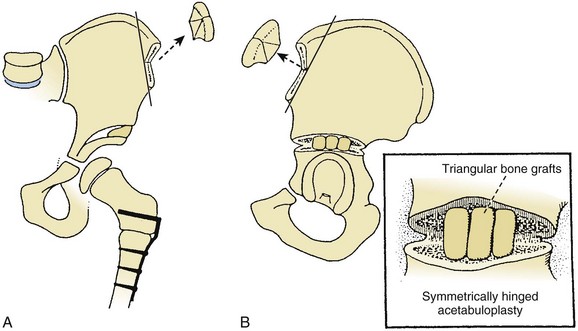

Spastic dislocation: Patients may benefit from open reduction, femoral shortening, varus derotation osteotomy, Dega osteotomy (Figure 3-11), triple osteotomy, or Chiari osteotomy.

Spastic dislocation: Patients may benefit from open reduction, femoral shortening, varus derotation osteotomy, Dega osteotomy (Figure 3-11), triple osteotomy, or Chiari osteotomy.

The type of pelvic osteotomy indicated is best determined in a three-dimensional CT scan, which demonstrates the area of acetabular deficiency (anterior, lateral, or posterior) and the congruency of the joint surfaces.

The type of pelvic osteotomy indicated is best determined in a three-dimensional CT scan, which demonstrates the area of acetabular deficiency (anterior, lateral, or posterior) and the congruency of the joint surfaces.

Addressing both hips can prevent dislocation of opposite hip.

Addressing both hips can prevent dislocation of opposite hip.

Late dislocations may best be left untreated or treated with a Schanz abduction osteotomy or a modified Girdlestone resection arthroplasty (resection below the lesser trochanter).

Late dislocations may best be left untreated or treated with a Schanz abduction osteotomy or a modified Girdlestone resection arthroplasty (resection below the lesser trochanter).

Windswept hips: characterized by abduction of one hip and adduction of the contralateral hip

Windswept hips: characterized by abduction of one hip and adduction of the contralateral hip

IX FOOT AND ANKLE ABNORMALITIES

1. Most common in spastic hemiplegia

Lengthening of the posterior tibialis is rarely sufficient.

Lengthening of the posterior tibialis is rarely sufficient.

Likewise, transfer of an entire muscle (posterior or anterior tibialis) is rarely recommended.

Likewise, transfer of an entire muscle (posterior or anterior tibialis) is rarely recommended.

Split-muscle transfers are helpful when the affected muscle is spastic during both the stance and swing phases of gait. The split–posterior tibialis transfer (rerouting half of the tendon dorsally to the peroneus brevis) is used in cases with spasticity of the muscle, flexible varus foot, and weak peroneal muscles.

Split-muscle transfers are helpful when the affected muscle is spastic during both the stance and swing phases of gait. The split–posterior tibialis transfer (rerouting half of the tendon dorsally to the peroneus brevis) is used in cases with spasticity of the muscle, flexible varus foot, and weak peroneal muscles.

Complications include decreased foot dorsiflexion. Split–anterior tibialis transfer (rerouting half of its tendon laterally to the cuboid) is used in patients with spasticity of the muscle and a flexible varus deformity.

Complications include decreased foot dorsiflexion. Split–anterior tibialis transfer (rerouting half of its tendon laterally to the cuboid) is used in patients with spasticity of the muscle and a flexible varus deformity.

Most often it is coupled with Achilles tendon lengthening and posterior tibial tendon intramuscular lengthening (Rancho procedure) to treat the fixed equinus contracture.

Most often it is coupled with Achilles tendon lengthening and posterior tibial tendon intramuscular lengthening (Rancho procedure) to treat the fixed equinus contracture.

section 7 Neuromuscular Disorders

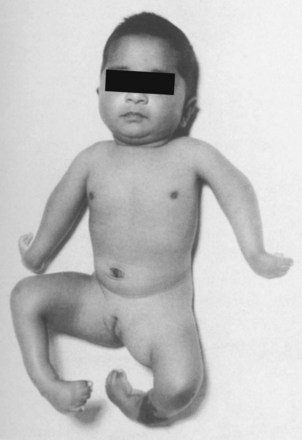

A Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (amyoplasia): nonprogressive disorder with multiple joints that are congenitally rigid (Figure 3-12). This disorder can be myopathic, neuropathic, or both and is associated with a decrease in anterior horn cells and other neural elements of the spinal cord. Intelligence is normal.

Evaluation should include neurologic studies, enzyme tests, and muscle biopsy (at 3 to 4 months of age).

Evaluation should include neurologic studies, enzyme tests, and muscle biopsy (at 3 to 4 months of age).

Affected patients typically have normal facies, normal intelligence, multiple joint contractures, and no visceral abnormalities.

Affected patients typically have normal facies, normal intelligence, multiple joint contractures, and no visceral abnormalities.

Upper extremity involvement usually includes adduction and internal rotation of the shoulder, extension of the elbow, and flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist. The elbow has no creases. These patients have an ability to use the feet as functional appendages.

Upper extremity involvement usually includes adduction and internal rotation of the shoulder, extension of the elbow, and flexion and ulnar deviation of the wrist. The elbow has no creases. These patients have an ability to use the feet as functional appendages.

Lower extremity involvement includes teratologic hip dislocations, knee contractures, resistant clubfeet, and vertical talus.

Lower extremity involvement includes teratologic hip dislocations, knee contractures, resistant clubfeet, and vertical talus.

The spine may be involved, with characteristic C-shaped (neuromuscular) scoliosis (33% of cases).

The spine may be involved, with characteristic C-shaped (neuromuscular) scoliosis (33% of cases).

Passive manipulation and serial casting

Passive manipulation and serial casting

Active elbow flexion achieved through anterior triceps transfer and posterior soft tissue release

Active elbow flexion achieved through anterior triceps transfer and posterior soft tissue release

Osteotomies are also considered after 4 years of age to allow independent eating.

Osteotomies are also considered after 4 years of age to allow independent eating.

One upper extremity should be left in extension at the elbow for positioning and perineal care and the other elbow in flexion for feeding.

One upper extremity should be left in extension at the elbow for positioning and perineal care and the other elbow in flexion for feeding.

Unilateral: medial open reduction with possible femoral shortening

Unilateral: medial open reduction with possible femoral shortening

Bilateral: typically left unreduced because ambulation is often preserved

Bilateral: typically left unreduced because ambulation is often preserved

Knee contractures are treated with early (at ages 6 to 9 months) soft tissue releases (especially hamstrings).

Knee contractures are treated with early (at ages 6 to 9 months) soft tissue releases (especially hamstrings).

The foot deformities (clubfoot and vertical talus) are initially treated with a soft tissue release, but later recurrences may necessitate bone procedures (talectomy). The goal is for the foot to be stiff and plantigrade in order to wear shoes and possibly ambulate.

The foot deformities (clubfoot and vertical talus) are initially treated with a soft tissue release, but later recurrences may necessitate bone procedures (talectomy). The goal is for the foot to be stiff and plantigrade in order to wear shoes and possibly ambulate.

Knee contractures should be corrected before hip reduction in order to maintain the reduction.

Knee contractures should be corrected before hip reduction in order to maintain the reduction.

B Distal arthrogryposis syndrome

Autosomal dominant disorder that affects predominantly the hands and feet

Autosomal dominant disorder that affects predominantly the hands and feet

Ulnarly deviated fingers (at metacarpal joints), metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal flexion contractures, and adducted thumbs with web space thickening are common.

Ulnarly deviated fingers (at metacarpal joints), metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal flexion contractures, and adducted thumbs with web space thickening are common.

Clubfoot and vertical talus deformities are common in the feet.

Clubfoot and vertical talus deformities are common in the feet.

Similar to arthrogryposis in clinical appearance, but joints are less rigid.

Similar to arthrogryposis in clinical appearance, but joints are less rigid.

Characterized primarily by multiple joint dislocations (including bilateral congenital knee dislocations), flattened facies, scoliosis, and clubfeet.

Characterized primarily by multiple joint dislocations (including bilateral congenital knee dislocations), flattened facies, scoliosis, and clubfeet.

Cervical kyphosis (watch for late myelopathy) is important to recognize early.

Cervical kyphosis (watch for late myelopathy) is important to recognize early.

II MYELODYSPLASIA (SPINA BIFIDA)

Disorder of incomplete spinal cord closure or rupture of the developing cord secondary to hydrocephalus

Disorder of incomplete spinal cord closure or rupture of the developing cord secondary to hydrocephalus

Spina bifida occulta: defect in the vertebral arch, with confined cord and meninges

Spina bifida occulta: defect in the vertebral arch, with confined cord and meninges

Meningocele: sac without neural elements protruding through the defect

Meningocele: sac without neural elements protruding through the defect

Myelomeningocele: in spina bifida, the sac with neural elements protrudes through the skin

Myelomeningocele: in spina bifida, the sac with neural elements protrudes through the skin

Rachischisis: neural elements exposed, with no covering

Rachischisis: neural elements exposed, with no covering

Function is related primarily to the level of the defect and the associated congenital abnormalities.

Function is related primarily to the level of the defect and the associated congenital abnormalities.

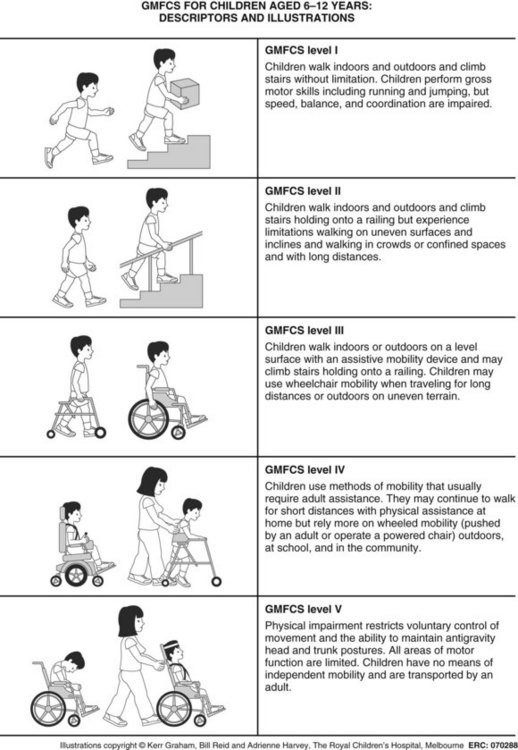

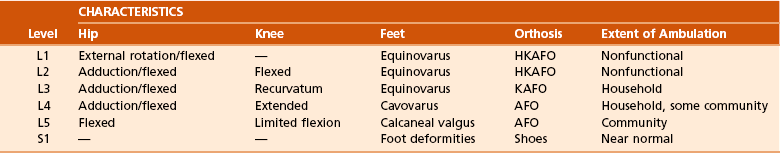

The myelodysplasia level is based on the lowest functional level (Table 3-7). L4 is a key level because the quadriceps can function and allow independent ambulation around the community (Figure 3-13).

The myelodysplasia level is based on the lowest functional level (Table 3-7). L4 is a key level because the quadriceps can function and allow independent ambulation around the community (Figure 3-13).

Can be diagnosed in utero (increased levels of α-fetoprotein)

Can be diagnosed in utero (increased levels of α-fetoprotein)

Related to a folate deficiency in utero

Related to a folate deficiency in utero

A type II Arnold-Chiari malformation is the most common comorbid condition.

A type II Arnold-Chiari malformation is the most common comorbid condition.

Sudden changes in function (rapid increase of scoliotic curvature, spasticity, new neurologic deficit, or increase in urinary tract infections) can be associated with tethered cord, hydrocephalus (most common), or syringomyelia.

Sudden changes in function (rapid increase of scoliotic curvature, spasticity, new neurologic deficit, or increase in urinary tract infections) can be associated with tethered cord, hydrocephalus (most common), or syringomyelia.

Head CT scans (70% of myelodysplastic patients have hydrocephalus) and myelography or spinal MRI are required.

Head CT scans (70% of myelodysplastic patients have hydrocephalus) and myelography or spinal MRI are required.

Fractures are also common in myelodysplasia, most often about the knee and hip in children 3 to 7 years of age, and can frequently be diagnosed only by noting redness, warmth, and swelling.

Fractures are also common in myelodysplasia, most often about the knee and hip in children 3 to 7 years of age, and can frequently be diagnosed only by noting redness, warmth, and swelling.

Fractures are commonly misdiagnosed as infection in these patients.

Fractures are commonly misdiagnosed as infection in these patients.

Fractures are treated conservatively, with a well-padded splint.

Fractures are treated conservatively, with a well-padded splint.

1. Careful observation of patients with myelodysplasia is important. Several myelodysplasia “milestones” have been developed to assess progress (Table 3-8).

Table 3-8

| Age (Months) | Function | Treatment |

| 4-6 | Head control | Positioning |

| 6-10 | Sitting | Supports/orthoses |

| 10-12 | Prone mobility | Prone board |

| 12-15 | Upright stance | Standing orthosis |

| 15-18 | Upright mobility | Trunk/extremity orthosis |

2. Treatment involves a team approach (urologist, orthopaedist, neurosurgeon, and developmental pediatrician) to allow maximal function consistent with the patient’s level and other abnormalities.

3. Proper use of orthoses is essential in patients with myelodysplasia. The determination of ambulation potential is based on the level of the deficit and motivation of the child.

4. Surgery for myelodysplasia focuses on balancing of muscles and correction of deformities.

5. Increased attention has been focused on latex sensitivity in myelodysplastic patients. A latex-free environment is necessary to prevent life-threatening allergic reactions.

1. A wide spectrum of hip disease occurs, including flexion contractures, hip subluxation and dislocation, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), and abduction or external rotation contracture. In general, management of the hip in patients with myelomeningocele is controversial.

Occur in patients with thoracic/high lumbar myelomeningocele as a result of unopposed hip flexors or in patients who sit most of the time

Occur in patients with thoracic/high lumbar myelomeningocele as a result of unopposed hip flexors or in patients who sit most of the time

Anterior hip release with tenotomy of the iliopsoas, sartorius, rectus femoris, and tensor fasciae latae

Anterior hip release with tenotomy of the iliopsoas, sartorius, rectus femoris, and tensor fasciae latae

For patients with lesions at the low lumbar level, the psoas should be preserved for independent ambulation.

For patients with lesions at the low lumbar level, the psoas should be preserved for independent ambulation.

Hip abduction contracture can cause pelvic obliquity and scoliosis; it is treated with proximal division of the tensor fasciae latae and distal iliotibial band release (Ober-Yount procedure).

Hip abduction contracture can cause pelvic obliquity and scoliosis; it is treated with proximal division of the tensor fasciae latae and distal iliotibial band release (Ober-Yount procedure).

Caused by paralysis of the hip abductors and extensors with unopposed hip flexors and adductors

Caused by paralysis of the hip abductors and extensors with unopposed hip flexors and adductors

Containment is controversial, but in general, it is considered essential only in patients with a functioning quadriceps.

Containment is controversial, but in general, it is considered essential only in patients with a functioning quadriceps.

Redislocation may occur no matter what treatment is used to maintain the reduction.

Redislocation may occur no matter what treatment is used to maintain the reduction.

Principles of treatment should follow those for any paralytic hip dislocation:

Principles of treatment should follow those for any paralytic hip dislocation:

Bony abnormality correction (femoral anteversion with valgus, posterior acetabular insufficiency)

Bony abnormality correction (femoral anteversion with valgus, posterior acetabular insufficiency)

Muscle balance correction by means of transfer or release (flexor-adductor, extensor-abductor balance)

Muscle balance correction by means of transfer or release (flexor-adductor, extensor-abductor balance)

Late dislocation at the low lumbar level may be caused by a tethered cord, which must be released before the hip is reduced.

Late dislocation at the low lumbar level may be caused by a tethered cord, which must be released before the hip is reduced.

The functional outcome of thoracic-level myelomeningocele is independent of whether the hips are in proper postion or dislocated.

The functional outcome of thoracic-level myelomeningocele is independent of whether the hips are in proper postion or dislocated.

1. Usually include quadriceps weakness (usually treated with knee-ankle-foot orthoses)

2. Flexion deformities are not problematic in patients who use wheelchairs but can be treated with hamstring release and posterior capsular release.

3. Recurvatum is rarely a problem and can be treated early with serial casting and knee-ankle-foot orthoses. Tenotomies (quadriceps lengthening) are sometimes required.

4. Valgus deformities are usually not a problem. Sometimes iliotibial band release, guided growth, or osteotomies are needed.

1. Objectives: (1) for feet to be braceable and plantigrade and (2) muscle balance

2. Calcaneal deformity (see Figure 3-13)

Often caused by unopposed action of the tibialis anterior in patients with paralysis at the lower lumbar level

Often caused by unopposed action of the tibialis anterior in patients with paralysis at the lower lumbar level

Predisposes to heel ulcers that can result in osteomyelitis of the calcaneus

Predisposes to heel ulcers that can result in osteomyelitis of the calcaneus

Passive stretching is initial treatment, but tibialis anterior transfer to the calcaneus is often required. At time of transfer, do not fix the foot in equinus position, as this predisposes to distal tibial metaphyseal fracture.

Passive stretching is initial treatment, but tibialis anterior transfer to the calcaneus is often required. At time of transfer, do not fix the foot in equinus position, as this predisposes to distal tibial metaphyseal fracture.

Valgus ankle deformity is common in ambulatory patients with the deformity in the distal tibia or subtalar joint (or both). Surgical correction is warranted when pressure sores are present and orthotics fail to hold correction.

Valgus ankle deformity is common in ambulatory patients with the deformity in the distal tibia or subtalar joint (or both). Surgical correction is warranted when pressure sores are present and orthotics fail to hold correction.

For skeletally immature patients: distal tibial hemiepiphysiodesis or Achilles tendon–fibular tenodesis

For skeletally immature patients: distal tibial hemiepiphysiodesis or Achilles tendon–fibular tenodesis

For skeletally mature patients: distal tibial osteotomy

For skeletally mature patients: distal tibial osteotomy

In subtalar region valgus, ankle-foot orthoses are often helpful, but tendon release (anterior tibialis, Achilles), posterior tibialis lengthening, and other procedures may be required. Triple arthrodesis should be avoided in most myelodysplastic patients and is used only for severe deformities with sensate feet.

In subtalar region valgus, ankle-foot orthoses are often helpful, but tendon release (anterior tibialis, Achilles), posterior tibialis lengthening, and other procedures may be required. Triple arthrodesis should be avoided in most myelodysplastic patients and is used only for severe deformities with sensate feet.

Secondary to retained activity or contracture of the tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior; common in patients with L4-level lesions

Secondary to retained activity or contracture of the tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior; common in patients with L4-level lesions

Treatment consists of complete subtalar release through a transverse (Cincinnati) incision, lengthening of the tibialis posterior and Achilles tendons, and transfer of the tibialis anterior tendon to the dorsal midfoot.

Treatment consists of complete subtalar release through a transverse (Cincinnati) incision, lengthening of the tibialis posterior and Achilles tendons, and transfer of the tibialis anterior tendon to the dorsal midfoot.

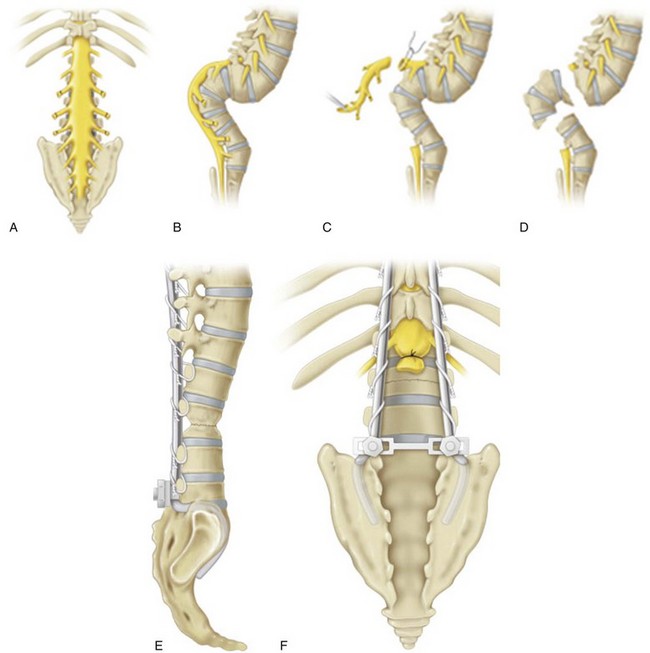

1. Lumbar kyphosis or other congenital malformation of the spine as a result of a lack of segmentation or formation (i.e., hemivertebrae, diastematomyelia, unsegmented bars).

Treatment of kyphosis is based on problems with skin breakdown or necessity of using upper extremities to hold up their torso.

Treatment of kyphosis is based on problems with skin breakdown or necessity of using upper extremities to hold up their torso.

Resection of the kyphosis (kyphectomy) with local fusion or fusion to the pelvis with instrumentation is required in severe cases (Figure 3-14).

Resection of the kyphosis (kyphectomy) with local fusion or fusion to the pelvis with instrumentation is required in severe cases (Figure 3-14).

2. Scoliosis can also occur with severe lordosis as a result of muscular imbalance that is caused by thoracic-level paraplegia.

Nearly all patients with thoracic-level paraplegia develop scoliosis.

Nearly all patients with thoracic-level paraplegia develop scoliosis.

Bracing is generally unsuccessful in treating these spinal deformities.

Bracing is generally unsuccessful in treating these spinal deformities.

Rapid curve progression can be associated with hydrocephalus or a tethered cord, which may be manifested as lower extremity spasticity or an increase in urinary tract infections.

Rapid curve progression can be associated with hydrocephalus or a tethered cord, which may be manifested as lower extremity spasticity or an increase in urinary tract infections.

III MYOPATHIES (MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES)

1. These noninflammatory, inherited disorders are characterized by progressive muscle weakness.

2. Treatment focuses on physical therapy, orthoses, genetic counseling, and surgery.

3. Several types of muscular dystrophy are classified on the basis of their inheritance patterns.

Markedly elevated creatine phosphokinase level and absence of dystrophin protein on muscle biopsy and DNA testing.

Markedly elevated creatine phosphokinase level and absence of dystrophin protein on muscle biopsy and DNA testing.

A muscle biopsy sample shows foci of necrosis and connective tissue infiltration.

A muscle biopsy sample shows foci of necrosis and connective tissue infiltration.

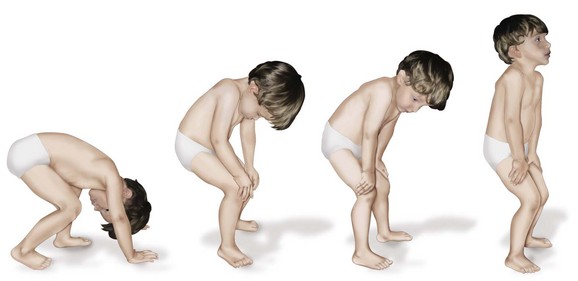

2. Physical findings manifested as muscle weakness (proximal groups weaker than distal), clumsy walking, decreased motor skills, lumbar lordosis, calf pseudohypertrophy, a positive Gowers sign (rises by walking the hands up the legs to compensate for gluteus maximus and quadriceps weakness; Figure 3-15). Hip extensors are typically the first muscle group affected.

Goals are to keep patients ambulatory as long as possible.

Goals are to keep patients ambulatory as long as possible.

Patients lose independent ambulation by age 10; although it is controversial, the use of knee-ankle-foot orthoses and release of contractures can extend walking ability for 2 to 3 years.

Patients lose independent ambulation by age 10; although it is controversial, the use of knee-ankle-foot orthoses and release of contractures can extend walking ability for 2 to 3 years.

Patients are usually wheelchair dependent by age 15 years.

Patients are usually wheelchair dependent by age 15 years.

Patients usually die of cardiorespiratory complications before age 20.

Patients usually die of cardiorespiratory complications before age 20.

Newer medical treatment includes high-dose steroids, which have been shown to prevent scoliosis formation and prolong walking ability.

Newer medical treatment includes high-dose steroids, which have been shown to prevent scoliosis formation and prolong walking ability.

With no muscle support, scoliosis rapidly progresses in virtually all patients by age 14 years.

With no muscle support, scoliosis rapidly progresses in virtually all patients by age 14 years.

Patients can become bedridden by age 16 as a result of spinal deformity and are unable to sit for more than 8 hours.

Patients can become bedridden by age 16 as a result of spinal deformity and are unable to sit for more than 8 hours.

Forced vital capacity decreases by 4% each year and another 4% for every 10 degrees of thoracic scoliosis.

Forced vital capacity decreases by 4% each year and another 4% for every 10 degrees of thoracic scoliosis.

Scoliosis should be treated early (at 25 to 30 degrees of curvature) before pulmonary and cardiac function deteriorate.

Scoliosis should be treated early (at 25 to 30 degrees of curvature) before pulmonary and cardiac function deteriorate.

The surgical approach includes posterior spinal fusion with segmental instrumentation to include the pelvis.

The surgical approach includes posterior spinal fusion with segmental instrumentation to include the pelvis.

C Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

Autosomal dominant disorder typically observed in patients 6 to 20 years of age with facial muscle abnormalities, normal creatine phosphokinase level, and winging of the scapula

Autosomal dominant disorder typically observed in patients 6 to 20 years of age with facial muscle abnormalities, normal creatine phosphokinase level, and winging of the scapula

2. Treated with stabilization by means of scapulothoracic fusion

D Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

IV POLYMYOSITIS AND DERMATOMYOSITIS

1. Manifest with a febrile illness that may be acute or insidious

2. Females predominate and typically exhibit photosensitivity and increased creatine phosphokinase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) values.

3. Muscles are tender, brawny, and indurated. Biopsy findings demonstrate the pathognomonic inflammatory response.

A Disorders associated with multiple central nervous system lesions

Autosomal recessive disorder with problems with the frataxin gene

Autosomal recessive disorder with problems with the frataxin gene

Spinocerebellar degenerative disease with mean onset between 7 and 15 years of age

Spinocerebellar degenerative disease with mean onset between 7 and 15 years of age

Manifests with staggering, wide-based gait; nystagmus; cardiomyopathy; a cavus foot; and scoliosis

Manifests with staggering, wide-based gait; nystagmus; cardiomyopathy; a cavus foot; and scoliosis

Involves motor and sensory defects, with an increase in polyphasic potentials on electromyograms

Involves motor and sensory defects, with an increase in polyphasic potentials on electromyograms

Use of a wheelchair is needed by age 15, and death occurs between ages 40 and 50, usually from cardiomyopathy.

Use of a wheelchair is needed by age 15, and death occurs between ages 40 and 50, usually from cardiomyopathy.

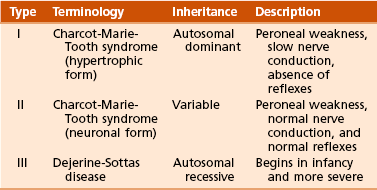

C Hereditary sensory motor neuropathies: a group of inherited neuropathic disorders with similar characteristics (Table 3-9)

D Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (peroneal muscular atrophy)

Autosomal dominant sensory motor demyelinating neuropathy

Autosomal dominant sensory motor demyelinating neuropathy

Two forms are described: a hypertrophic form with onset during the second decade of life, and a neuronal form with onset during the third or fourth decade but with more extensive foot involvement.

Two forms are described: a hypertrophic form with onset during the second decade of life, and a neuronal form with onset during the third or fourth decade but with more extensive foot involvement.

Orthopaedic manifestations include pes cavus, hammer toes with frequent corns and calluses, peroneal weakness, and muscular atrophy usually distal to the knees (“stork legs”).

Orthopaedic manifestations include pes cavus, hammer toes with frequent corns and calluses, peroneal weakness, and muscular atrophy usually distal to the knees (“stork legs”).

Involves motor defects much more than sensory defects.

Involves motor defects much more than sensory defects.

Low nerve conduction velocities with prolonged distal latencies are noted in peroneal, ulnar, and median nerves.

Low nerve conduction velocities with prolonged distal latencies are noted in peroneal, ulnar, and median nerves.

Diagnosis is made most reliably by DNA testing for a duplication of a genomic fragment that encompasses the peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP22) gene on chromosome 17.

Diagnosis is made most reliably by DNA testing for a duplication of a genomic fragment that encompasses the peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP22) gene on chromosome 17.

Intrinsic wasting is noted in the hands.

Intrinsic wasting is noted in the hands.

The most severely affected muscles are the tibialis anterior, peroneus longus, and peroneus brevis.

The most severely affected muscles are the tibialis anterior, peroneus longus, and peroneus brevis.

Plantar release, posterior tibial tendon transfer (if hindfoot varus is flexible)

Plantar release, posterior tibial tendon transfer (if hindfoot varus is flexible)

Triple arthrodesis (poor long-term results) versus calcaneal and metatarsal osteotomies (if heel varus is fixed and the foot not too short)

Triple arthrodesis (poor long-term results) versus calcaneal and metatarsal osteotomies (if heel varus is fixed and the foot not too short)

The Jones procedure for hammer toes, and intrinsic procedures for hand deformity

The Jones procedure for hammer toes, and intrinsic procedures for hand deformity

The Coleman block test, to help decide whether calcaneal osteotomy is needed

The Coleman block test, to help decide whether calcaneal osteotomy is needed

1. Chronic disease with insidious development of easy muscle fatigability after exercise

2. Caused by competitive inhibition of acetylcholine receptors at the motor end plate by antibodies produced in the thymus gland

B Treatment consists of cyclosporin, anti-acetylcholinesterase agents, or thymectomy.

VII ANTERIOR HORN CELL DISORDERS

Viral destruction of anterior horn cells in the spinal cord and brainstem motor nuclei

Viral destruction of anterior horn cells in the spinal cord and brainstem motor nuclei

This disease all but disappeared in the United States after vaccine was developed. However, it is still common in underdeveloped countries and in locales where vaccination is unpopular.

This disease all but disappeared in the United States after vaccine was developed. However, it is still common in underdeveloped countries and in locales where vaccination is unpopular.

Many surgical procedures in current use were originally developed for the treatment of polio.

Many surgical procedures in current use were originally developed for the treatment of polio.

The hallmark of polio is muscle weakness with normal sensation.

The hallmark of polio is muscle weakness with normal sensation.

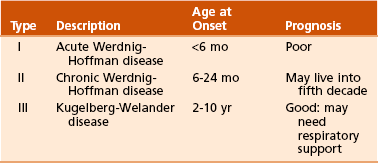

Autosomal recessive, associated with survival motor neuron gene (SMN)

Autosomal recessive, associated with survival motor neuron gene (SMN)

Loss of anterior horn cells from the spinal cord. There are three types (Table 3-10).

Loss of anterior horn cells from the spinal cord. There are three types (Table 3-10).

Patients have symmetric paresis with more involvement of the lower extremity and proximal muscles.

Patients have symmetric paresis with more involvement of the lower extremity and proximal muscles.

Hip subluxation or dislocation is common and treated nonoperatively.

Hip subluxation or dislocation is common and treated nonoperatively.

2. Scoliosis is treated surgically, like Duchenne muscular dystrophy curves, except that fusion may be required while patient is still ambulatory (may result in loss of ambulatory ability).

VIII ACUTE IDIOPATHIC POSTINFECTIOUS POLYNEUROPATHY (GUILLAIN-BARRÉ SYNDROME)