Chapter 437 Pediatric Heart and Heart-Lung Transplantation

437.1 Pediatric Heart Transplantation

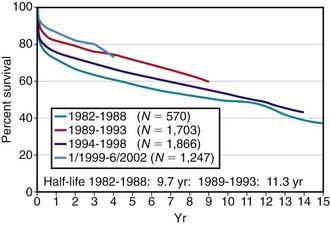

Pediatric heart transplantation is standard therapy for children with end-stage cardiomyopathy and other lesions not amenable to surgical repair. As of 2005, >6,900 heart transplants had been performed on children in the USA, with ≈375 transplants annually. Survival rates among children compare favorably with those of adults. For children transplanted in the 1980s and early 1990s, 1 yr survival has been 75-80%, whereas for those transplanted after 2000, 1 yr survival is now in the range of 90%; during the same time periods, 5 yr survival has improved from 60-65% to 75% (see ![]() Fig. 437-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). A growing number of children are now reaching their 15, 20, and 30 yr post-transplant anniversaries.

Fig. 437-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). A growing number of children are now reaching their 15, 20, and 30 yr post-transplant anniversaries.

Recipient and Donor Selection

Potential heart transplant recipients must be free of serious noncardiac medical problems such as neurologic disease, systemic infection, severe hepatic or renal disease, or severe malnutrition. Many children with ventricular dysfunction may have pulmonary hypertension and even pulmonary vascular disease, which would preclude heart transplantation; pulmonary vascular resistance must be measured at cardiac catheterization, both at rest and in response to vasodilators. Patients with fixed elevated pulmonary vascular resistance are at higher risk for heart transplantation and may be considered candidates for either heterotopic heart transplantation (see later) or heart-lung transplantation (Chapter 437.2). A comprehensive social services evaluation is an important component of the recipient evaluation. Because of the complex post-transplantation medical regimen, the family must have a history of compliance. Detailed informed consent must be obtained.

The decision of when to place a patient on the transplant waiting list is based on a combination of many factors, including extremely poor ventricular function (left ventricular fractional shortening <10%; normal is 28-40%), poor exercise tolerance as determined by cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Chapter 417.5), poor response to medical anticongestive therapy, multiple hospitalizations for heart failure, arrhythmia, progressive deterioration in renal or hepatic function, early stages of pulmonary vascular disease, and poor nutritional status. In patients awaiting transplantation, those with poor left ventricular function (fractional shortening <15%) are usually started on a regimen of anticoagulation to reduce the risk of mural thrombosis and thromboembolism. Patients with cardiogenic shock unresponsive to standard pharmacologic treatment may be candidates for placement of left ventricular (LVAD) or biventricular (BiVAD) assist devices, or for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support, which can stabilize hemodynamics and serve as a bridge to transplantation (Chapter 436).

Complications of Immunosuppression

Infection

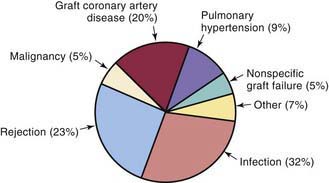

Infection is 1 of the 2 leading causes of death in pediatric transplant patients (Fig. 437-2). The incidence of infection is greatest in the 1st 3 mo after transplantation when immunosuppressive doses are highest. Viral infections are the most common, especially cytomegalovirus, which accounts for as many as 25% of infectious episodes. Cytomegalovirus infection may occur as a primary infection in patients without previous exposure to the virus or as a reactivation. Severe cytomegalovirus infection can be disseminated or associated with pneumonitis or gastroenteritis and may provoke an episode of acute graft rejection or graft coronary disease. Most centers use intravenous ganciclovir or cytomegalovirus immune globulin (CytoGam), or both, as prophylaxis in any patient receiving a heart from a donor who is positive for cytomegalovirus or in any recipient who has serologic evidence of previous cytomegalovirus disease. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enhances the ability to diagnose cytomegalovirus infection and to monitor the efficacy of therapy serially. Oral preparations of ganciclovir with improved absorption profiles are available for chronic therapy and have largely replaced intravenous preparations for prophylaxis.

Almond CS, Thiagarajan RR, Piercey GE, et al. Waiting list mortality among children listed for heart transplantation in the United States. Circulation. 2009;119:717-727.

Bernstein D, Naftel D, Chin C, et al. Pediatric Heart Transplant Study. Outcome of listing for cardiac transplantation for failed Fontan: a multi-institutional study. Circulation. 2006;114:273-280.

Boucek MM, Aurora P, Edwards LB, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: tenth official pediatric heart transplantation report—2007. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:796-807.

Boucek MM, Mashburn C, Dunn SM, et al. Pediatric heart transplantation after declaration of cardiocirculatory death. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:709-714.

Canter CE, Shaddy RE, Bernstein D, et al. Indications for heart transplantation in pediatric heart disease. Circulation. 2007;115:658-676.

Chin C, Lukito SS, Shek J, et al. Prevention of pediatric graft coronary artery disease: atorvastatin. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:442-446.

Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, et al. Noninvasive discrimination of rejection in cardiac allograft recipients using gene expression profiling. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:150-160.

Fan X, Ang A, Pollock-Barziv SM, et al. Donor-specific B-cell tolerance after ABO-incompatible infant heart transplantation. Nat Med. 2004;10:1227-1233.

Girnita DM, Brooks MM, Webber SA, et al. Genetic polymorphisms impact the risk of acute rejection in pediatric heart transplantation: a multi-institutional study. Transplantation. 2008;85:1632-1639.

Kulikowska A, Boslaugh SE, Huddleston CB, et al. Infectious, malignant, and autoimmune complications in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Pediatr. 2008;152:671-677.

Pollock-BarZiv SM, Anthony SJ, Niedra R, et al. Quality of life and function following cardiac transplantation in adolescents. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:2468-2470.

Ringewald JM, Gidding SS, Crawford SE, et al. Nonadherence is associated with late rejection in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Pediatr. 2001;139:75-78.

Rosenthal DN, Chin C, Nishimura K, et al. Identifying cardiac transplant rejection in children: diagnostic utility of echocardiography, right heart catheterization and endomyocardial biopsy data. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:323-329.

Ross M, Kouretas P, Gamberg P, et al. Ten- and 20-year survivors of pediatric orthotopic heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:261-270.

Russo LM, Webber SA. Pediatric heart transplantation: immunosuppression and its complications. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:104-109.

Tsang V, Yacoub M, Sridharan S, et al. Late donor cardiectomy after paediatric heterotopic cardiac transplantation. Lancet. 2009;374:387-392.

Webber SA. Immunology of pediatric heart transplantation: a clinical update. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2001;4:158-184.

Webber SA, Naftel DC, Fricker FJ, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders after pediatric heart transplantation: a multi-institutional study. Lancet. 2006;367:233-239.

West LJ, Pollock-Barziv SM, Dipchand AI, et al. ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:793-800.

437.2 Heart-Lung and Lung Transplantation

More than 700 heart-lung and lung (single or double) transplants have been performed in children in the USA, with ≈60 procedures performed annually. Primary indications for heart-lung transplantation include cystic fibrosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, complex congenital heart disease with pulmonary hypoplasia or Eisenmenger syndrome, congenital lung abnormalities, and end-stage parenchymal lung disease (bronchopulmonary dysplasia, chronic lung disease, and interstitial fibrosis). Many of these patients with normal hearts may also be candidates for single- or double-lung transplantation if right ventricular function is preserved. In some patients with Eisenmenger physiology, double-lung transplantation can be performed in combination with repair of intracardiac defects. Patients with cystic fibrosis are not candidates for single-lung grafts because of the risk of infection from the diseased contralateral lung. Patients are selected according to many of the same criteria as for heart transplant recipients (Chapter 437.1).

Post-transplant immunosuppression is usually achieved with a triple-drug regimen, similar to that used for heart transplantation. Unlike patients with isolated heart transplants, few patients with lung transplants can be weaned totally off steroids. Prophylaxis against P. carinii infection is achieved with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or aerosolized pentamidine. Ganciclovir and cytomegalovirus immune globulin prophylaxis are used as in heart transplant recipients (Chapter 437.1).

Aurora P, Boucek MM, Christie J, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: tenth official pediatric lung and heart/lung transplantation report—2007. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:1223-1228.

Moffatt SD, Demers P, Robbins RC, et al. Lung transplantation: a decade of experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:145-151.

Sritippayawan S, Keens TG, Horn MV, et al. What are the best pulmonary function test parameters for early detection of post-lung transplant bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in children? Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7:200-203.

Starnes VA, Bowdish ME, Woo MS, et al. A decade of living lobar lung transplantation: recipient outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:114-122.

Webber SA, McCurry K, Zeevi A. Heart and lung transplantation in children. Lancet. 2006;368:53-68.