20 Pediatric Genitourinary and Renal Disorders

• Children often cannot differentiate between abdominal pain and groin pain—a complete physical examination is therefore necessary.

• The pathophysiology, clinical findings, and treatment of paraphimosis, testicular torsion, and priapism are similar in both the pediatric and adult population. They are emergencies that require immediate intervention.

• The most common cause of acute renal failure in children is hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

• Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is the most common cause of acute glomerulonephritis. IgA nephropathy is the most commonly diagnosed cause of glomerulonephritis in adolescents.

• One third of patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura have renal involvement. This disorder is the most common form of vasculitis in childhood and is usually characterized by the triad of abdominal pain, arthritis, and purpura.

Genitourinary Disorders

Hydrocele

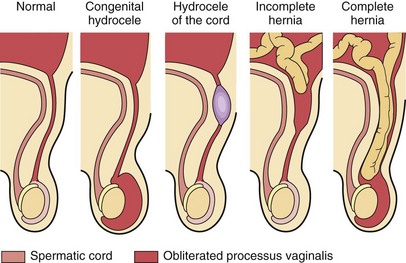

A hydrocele (Fig. 20.1) is a collection of fluid that accumulates within the layers of the tunica vaginalis and may or may not communicate with the peritoneal space. Hydroceles are often present at birth and occur most frequently on the right side because of delayed migration of the right testicle. Noncommunicating hydroceles in older children and adolescents should prompt examination for epididymitis, orchitis, trauma, tumor, or testicular torsion.

Fig. 20.1 Abnormalities of the processus vaginalis.

(From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007. Fig. 17-133.)

Varicocele

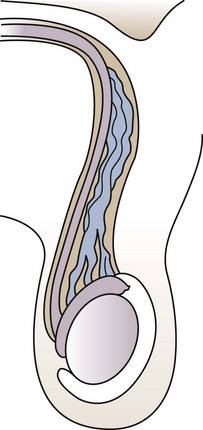

A varicocele is a collection of spermatic venous varicosities in the scrotum caused by incomplete drainage of the pampiniform plexus (Fig. 20.2). They are rare in children younger than 10 years. Varicoceles most commonly develop between 10 and 15 years of age and have an incidence of approximately 15% in males.1,2 The majority (85% to 95%) of varicoceles are left sided, the result of spermatic venous incompetence secondary to drainage of the left spermatic vein into the renal vein at a right angle.

Fig. 20.2 Varicocele.

(From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007. Fig. 14-44.)

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

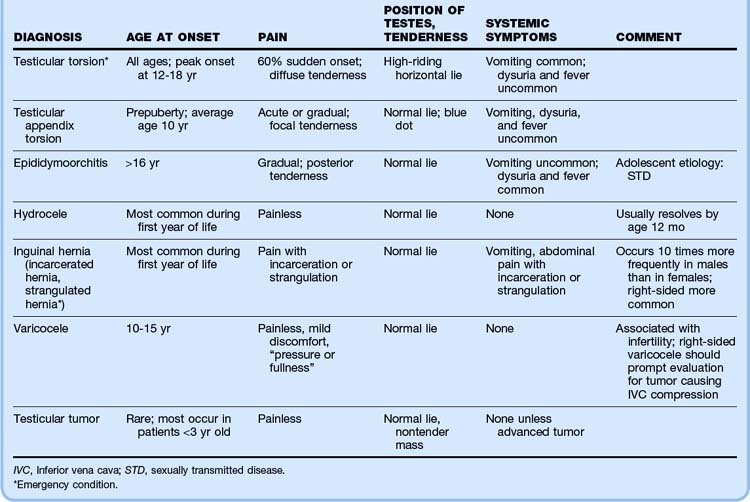

Right-sided varicoceles should prompt an evaluation for intraabdominal pathology such as thrombosis or a tumor causing compression of the inferior vena cava.3 Similarly, sudden onset of a left-sided varicocele should raise suspicion for renal cell carcinoma with obstruction of the left renal vein. The differential diagnosis of varicoceles and other scrotal masses is outlined in Table 20.1.

Testicular Torsion

The pathophysiology, clinical findings, and treatment of testicular torsion in the pediatric population is similar to that in adults. Detailed discussion of torsion can be found in Chapter 111.

Inguinal Hernia

An inguinal hernia occurs when an intraabdominal organ, usually intestine, herniates into a patent processus vaginalis (see Fig. 20.1). An incarcerated hernia refers to an intestinal loop that is not reducible. A strangulated hernia results when the blood supply to the intestinal loop is obstructed and bowel ischemia ensues.

Phimosis

Phimosis is a constriction of the penile foreskin that results in an inability to retract the prepuce over the glans. A fully retractable foreskin is present in 4% of newborns, 50% of 1-year-olds, 80% of 2-year-olds, and 90% of 4-year-olds. In the remaining cases, the foreskin may not be retractable until puberty.4

Paraphimosis

Paraphimosis is a urologic emergency in which the foreskin of an uncircumcised male is retracted behind the glans penis and acts as a constricting band (Fig. 20.3). The resulting venous and lymphatic congestion precludes returning the foreskin to its normal position, threatens arterial blood flow to the glans penis, and can result in penile necrosis, gangrene, or infarction of the glans over a period of hours to days. In infants and young boys, paraphimosis most commonly results after cleaning by a caretaker.

Fig. 20.3 Paraphimosis in a catheterized patient with an edematous prepuce proximal to the glans.

(From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2007.)

Balanitis and Balanoposthitis

Balanitis is an infection of the glans penis, whereas balanoposthitis is an infection of the foreskin in addition to the glans. Balanitis occurs in approximately 3% of boys, usually between 2 and 5 years of age, especially if they are uncircumcised.6

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Balanitis and balanoposthitis can be caused by trauma; by irritation such as contact dermatitis from urine, soaps, powders, and ointments; or by infection. Causative agents of infectious balanoposthitis include group A streptococci (GAS), anaerobic bacteria, Candida, and sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. Most children with GAS balanoposthitis have a characteristic moist balanoposthitis caused by a nonretractable prepuce, often in conjunction with a current or recent GAS infection at another site.7 Signs of group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection include pain, intense fiery redness, and a moist, glistening transudate or exudate under the prepuce. Streptococcal infection can be diagnosed by rapid antigen detection and culture.

Gonorrhea and chlamydial infection without frank urethral discharge are unusual in preschool children; however, after puberty, gonorrhea may be detected in the absence of urethral discharge.8 In severe cases, cellulitis can extend down the penile shaft. Palpable inguinal adenopathy is often present.

Urethral Prolapse

Prolapse of the urethra is most common in young African American girls (Fig. 20.4). The prolapsed mucosa is visible and may be irritated, congested, and hemorrhagic. Though quite alarming on physical examination, it is not associated with sexual abuse. Treatment consists of sitz baths three times a day.

Renal Disorders

Nephrotic Syndrome

• Hypoproteinemia (serum albumin <3 g/dL)

• Marked proteinuria (>40 g/m2/hr in a 24-hour period)

• Hyperlipidemia (predominantly triglycerides and cholesterol)

Disposition

Admission Criteria

• Any infant with nephrotic syndrome

• Any patient with respiratory distress or shock

• Nephrotic patients with infections, unexplained fever, refractory edema, renal insufficiency, dehydration, abdominal complaints, or hemoconcentration greater than 50%

• Patients with newly diagnosed nephrotic syndrome to complete the evaluation and educate the parents about outpatient management

Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome is defined by the presence of the classic triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure (Box 20.1).

Diagnostic Testing

A complete blood count may show leukocytosis, profound anemia (with hemoglobin levels of 5 to 9 g/dL), and mild to moderate thrombocytopenia (platelet counts are generally around 40,000/mm3).

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Clinical Presentation

The signs and symptoms of acute glomerulonephritis are presented in Box 20.2.

IgA Nephropathy

IgA nephropathy, also known as Berger disease, is the type of glomerulonephritis most commonly diagnosed in adolescence.9 This disease accounts for up to 25% of cases of glomerulonephritis in Asia and Europe and up to 10% in the United States.

Renal Tubular Acidosis

Urinary Retention

Urinary retention is defined as failure to urinate for more than 12 hours. More than 90% of all newborns void within the first 24 hours of life and 99% within the first 48 hours. In male children, posterior urethral valves are the most common cause of retention. Other causes include urethral polyps, urethral stricture, urethral diverticulum, meatal stenosis, and fecal impaction. In female infants, the differential diagnosis includes prolapsing ureterocele, urethral prolapse, and foreign bodies. Infections, medications, spinal cord abnormalities, and sexual abuse can cause retention in both male and female children. Diagnostic tests in the ED include blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urinalysis.10

1 Niedzielski J, Paduch D, Raczynski P. Assessment of adolescent varicocele. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12:410–413.

2 Kass EJ. Adolescent varicocele. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:1559–1569.

3 Bomalaski MD, Mills JL, Argueso LR, et al. Iliac vein compression syndrome: an unusual cause of varicocele. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18:1064–1068.

4 Brown MR, Cartwright PC, Snow BW. Common office problems in pediatric urology and gynecology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1091–1115.

5 Van Howe RS. Cost-effective treatment of phimosis. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E43.

6 Winkler A, Kohan A. Genitourinary emergencies. In: Crain EF, Gershel JC. Clinical manual of emergency pediatrics. New York: McGraw Hill; 2003:257.

7 Waugh MA. Balanitis. Dermatol Clin. 1998;16:757–797.

8 Schwartz RH, Rushton HG. Acute balanoposthitis in young boys. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:176–177.

9 Lau KK, Wyatt RJ. Glomerulonephritis. Adolesc Med. 2005;16:67–85.

10 Handrigan MT, Thompson I, Foster M. Diagnostic procedures for the urogenital system. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:745–761.