CHAPTER 17 Pediatric cataract surgery

Clinical features, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis

Five components are needed to define a cataract: when they appear, the degree to which the opacity occupies the capsular bag, anatomically where in the lens the opacity lies, its etiology, and morphology. Cataracts may present at birth (congenital) or develop through the first few years of life (developmental); they may be total or partial; they may be nuclear (fetal or embryonal), sutural, lamellar, capsular (usually anterior) or subcapsular (usually posterior), or polar (posterior or anterior); they may be inherited or sporadic with the latter including the acquired variety such as infectious (in utero TORCH infections), metabolic (e.g. galactosemia, Lowe syndrome, galactokinase deficiency) or secondary to other ocular conditions (e.g. persistent fetal vasculature, PFV). Morphology of cataracts includes descriptions such as anterior pyramidal, membranous, pulverulent, blue dot, and other specific entities such as anterior or posterior lenticonus. Such specifications sometimes help with systemic diagnoses (e.g. anterior lenticonus should alert the surgeon to the possibility of Alport syndrome) while pyramidal cataracts are often associated with corneal astigmatism1.

Anatomical considerations

The average axial length of an infant is 16.5 mm at birth. There is a rapid growth of the eye in the first 18 months of life with an average growth of 3.75 mm. By 13 years of age the average axial length is 23 mm2. Parents often ask if an intraocular implant would have to be removed as the child’s eye grows; this is not so if the implant is placed in the bag. This is because once the lens fibres are removed the bag stops growing. It is therefore important to know that the capsular bag diameter also changes with age. (The capsular bag diameter for the purposes of understanding the dimension available for an implant to be placed is the diameter of the crystalline lens + 1 mm). On average, the capsular bag diameter is 7 mm at birth, 9 mm at 2 years, 9–10 mm at 5 years, 10–10.5 mm at 16 years, and 10.5 mm > 21 years of age2.

Fundamental principles and goals of surgery

There are three important fundamental principles for successful pediatric cataract surgery:

Indications for surgery

Dense bilateral total cataracts are the clearest indication for intervention. Partial cataracts can be more difficult to assess as can lamellar cataracts. In older children (usually over 4 years of age) a glare test should be adopted to see if the child’s visual acuity reduces. For unilateral cataracts controversy exists as to the usefulness of intervention especially when the better eye is unaffected and normal. Nevertheless, this author believes that as long as surgery is performed early (before 8 weeks) for unilateral cases, aggressive amblyopia therapy can lead to some useful vision4. If a child presents late with either unilateral or bilateral cataracts, old photos form younger ages of the child should be examined for ‘red eye’, indicating absence of significant opacity.

Preoperative assessment

The preoperative assessment in children is crucial. A systemic evaluation is necessary to ensure fitness for anesthetic and exclude any health threatening condition, e.g. metabolic disorder. In all cases where the retina cannot be visualized an ocular ultrasound should be performed. Preoperative assessment will also allow surgical planning. If a child has a microphthalmic eye or a capsular bag diameter of less than 8 mm then implantation with a common adult lens (total diameters range from 12 to 13.5 mm) may not be safe. Lensectomy can be considered under such circumstances and capsule sparing techniques can be used for possible secondary implantation when the child is older. Spontaneously dislocated lenses such as those seen in Marfan syndrome may have an implant sutured into the sclera5, but this is not a preferred technique for this author due to the high rates of lens dislocation and displacement.

Operation techniques

Since there is little evidence at present to suggest that in high risk groups, i.e. children under the age of 1 years, implantation of an IOL has a protective effect against developing glaucoma, this author prefers a corneal approach close to where the limbal vessels reach clear cornea. In this way the conjunctiva is spared in case filtration surgery may be needed for any secondary glaucoma in the future. In children all wounds should be sutured and using 10-0 vicryl the induced astigmatism has been shown to resolve after 6 weeks6.

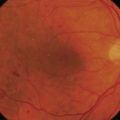

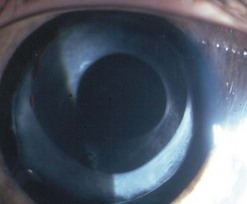

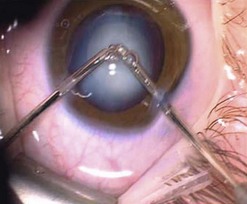

Capsulorrhexis in children is more difficult than in adults because of the increased elasticity of the capsule and the importance of being able to size the rhexis accurately so that the rhexis opening is smaller than the optic. This is important to prevent lens decentration and forward displacement of the IOL, which may lead to iris/optic capture (Figs 17.1 and 17.2). Therefore many techniques have been developed including diathermy, vitrectorrhexis, and TIPP rhexis (two incision push pull)7 (Fig. 17.3). The former two are unfortunately associated with an increased risk of tears within the rhexis during manipulation8,9. Accumulating evidence suggests that if the posterior capsule is left intact in children under the age of 610, visual axis opacification occurs very soon after surgery especially in children less than 2 years of age. Most authors also perform anterior vitrectomy. This author performs posterior capsulotomy with anterior vitrectomy in all children under 4 years of age; between 4 and 8 years only a posterior capsulotomy is performed and thereafter the posterior capsule is left intact. The rationale is that after 8 years of age most children are cooperative enough to allow YAG capsulotomy awake.

Fig. 17.1 The IOL is securely stable between the anterior and posterior rhexis. This is 5 years post-surgery.

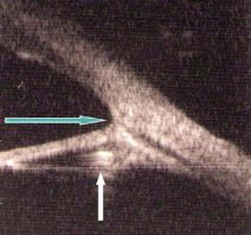

The technique of posterior capsulotomy also varies. The approach can be anterior or pars plicata/plana. In infants with axial lengths of less than 20 mm, it is usually easier to place the implant in the intact bag and then close the wound and fashion a pars plicata entry into the vitreous to perform posterior mechanical capsulotomy and anterior vitrectomy. It is worth noting that with an anterior approach it is important to keep the anterior hyaloids face intact until vitrectomy is done if planned; this avoids traction on the vitreous face, which may transmit to the vitreous base and can predispose to retinal detachment7. To this end it is worth remembering that Berger’s space is a potential space about 3.5–4.5 mm in diameter. This space can be expanded with viscoelastic to push the anterior hyaloids to face posteriorly.

The pediatric lens is very soft and can almost always be aspirated. Sometimes calcific components can be difficult to aspirate. During lens aspiration it is important in opaque lenses to aspirate the peripheral lens matter first before taking the central nucleus in case there is a posterior defect. If this is present and the central nucleus is taken first, there is a risk of vitreous traction when the peripheral lens matter is aspirated (Fig. 17.4).

Placing the implant is an important part of the technique. If there is a posterior capsulotomy already present, it is important to place the trailing haptic into the bag and not rotate the IOL to avoid posterior migration into the vitreous of the implant, especially in children less than 4 years of age. Viscoelastic can be left in the eye if necessary to stabilize the implant; if this is done Acetazolamide (4–7 mg/kg q.i.d) is needed for 2 days. Wherever possible it is important to place the IOL in bag and not the sulcus (Fig. 17.5), but of course there are exceptions such as secondary IOLS. In this latter case one piece rigid PMMA implants are more stable than three piece hydrophobic acrylic implants. Posterior capsule optic capture is favored by some authors; this technique is very useful if for some reason the anterior rhexis has a tear or if the child has aniridia and there is a worry about the size or stability of the anterior rhexis.

Intraoperative complications

Posterior capsulotomy may result in an opening too large for safe in the bag implantation of an IOL. IT IS REALLY IMPORTANT THAT AN IMPLANT IS NOT PLACED IN THE SUCLUS OF VERY YOUNG CHILDREN (see Fig. 17.5). It is safer to leave the eye aphakic and place a secondary implant 6 months later. Counseling parents preoperatively of this eventuality will save a protracted and anxious discussion after the event.

1 Amaya L, Taylor D, Russell-Eggitt I, et al. The morphology and natural history of childhood cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(2):125-144.

2 Wilson E, Apple D, Bluestein W. Intraocular lenses for pediatric implantation: Biomaterials, designs, and sizing. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20(6):584-591.

3 Wong IB, Sukthankar VD, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Incidence of early-onset glaucoma after infant cataract extraction with and without intraocular lens implantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(9):1200-1203.

4 Taylor D, Wright KW, Amaya L, et al. Should we aggressively treat unilateral congenital cataracts?: View 1. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(9):1120-1125.

5 Buckley EG. Safety of transscleral-sutured intraocular lenses in children. J AAPOS. 2008;12(5):431-439.

6 Spierer A, Bar-Sela S. Strabismus. 2004;41(1):35-38.

7 Hamada S, Low S, Walters BC, et al. Five-year experience of the 2-incision push–pull technique for anterior and posterior capsulorrhexis in pediatric cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(8):1309-1314.

8 Krag S, Thim K, Corydon L. Diathermic capsulotomy versus capsulorhexis: a biomechanical study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23(1):86-90.

9 Wilson ME, Saunders RA, Roberts EL, et al. Mechanized anterior capsulectomy as an alternative to manual capsulorhexis in children undergoing intraocular lens implantation. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33(4):237-240.

10 Jensen AA, Basti S, Greenwald MJ, et al. discussion 328. When may the posterior capsule be preserved in pediatric intraocular lens surgery? Ophthalmology. 2002;109(2):324-327.

to

to  a metre. Older children need bifocal prescription with a +3. Add to the distance prescription.

a metre. Older children need bifocal prescription with a +3. Add to the distance prescription.