Patient Education and Health Promotion

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

Write learning objectives in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains.

Write learning objectives in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains.

Compare and contrast how adults and children learn.

Compare and contrast how adults and children learn.

Describe the methods that are used to evaluate patient education.

Describe the methods that are used to evaluate patient education.

Explain the importance of health education.

Explain the importance of health education.

Identify the settings that are appropriate for the implementation of health promotion activities.

Identify the settings that are appropriate for the implementation of health promotion activities.

Describe the respiratory therapist’s role in a disease management program.

Describe the respiratory therapist’s role in a disease management program.

The top five causes of death in the United States are heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive lung disease (i.e., bronchitis and emphysema), and accidents.1 It is believed by most experts in health care that the majority of these illnesses are preventable. Public education about risk factors is the key to the prevention of these diseases and probably has the greatest potential for making an impact on health care in this country. Therefore, the emphasis in health care should be on health promotion and disease prevention. RTs will play a greater role in health promotion and prevention in the future.

Patient Education

Performance Objectives

Learning Domains

Cognitive Domain

1. List the indications for oxygen therapy.

2. Discuss the importance of using the prescribed liter flow.

Any factual information that you expect the patient to understand and apply falls under the cognitive domain. Action verbs for the cognitive domain are included in Table 49-1.2

TABLE 49-1

Verbs for the Cognitive Domain

| Purpose | Example Verbs |

| 1. Knowledge | Cite, define, read, identify, list, label, name, outline, recognize, select, state |

| 2. Comprehension | Convert, describe, defend, explain, illustrate, interpret, give examples of, predict, paraphrase, summarize, translate |

| 3. Application | Apply, compute, construct, demonstrate, change, calculate, use, estimate, modify, present, prepare, solve, proceed, relate, utilize |

| 4. Analysis | Analyze, associate, compare, contrast, determine, diagram, differentiate, discriminate, distinguish, outline, illustrate, separate |

| 5. Synthesis | Categorize, combine, compile, compose, create, design, develop, devise, integrate, modify, organize, plan, propose, rearrange, reorganize, revise, rewrite, translate, write |

| 6. Evaluation | Appraise, assess, compare, conclude, contrast, critique, discriminate, make a decision, support, evaluate, judge, weigh |

Modified from French D, Olrech N, Hale C, et al: Blended learning: an ongoing process for Internet integration, Victoria, Canada, 2003, Trafford Publishing.

Psychomotor Domain

Examples of action verbs for the psychomotor domain are included in Table 49-2.2

TABLE 49-2

Verbs for the Psychomotor Domain

| Purpose | Example Verbs |

| 1. Perception: prepares and recognizes sensory cues to want to respond | Detect, distinguish, differentiate, identify, isolate, relate, recognize, observe, perceive, see, watch |

| 2. Ready to act and respond | Begin, explain, move, react, show, state, establish a body position, place, posture, assume a stance, sit, stand, position |

| 3. Guided response: imitate and practice; rough sequencing of events | Copy, duplicate, imitate, manipulate, operate, try, practice, dismantle |

| 4. Efficiency: smooth sequencing of events | Assemble, calibrate, construct, display, fasten, fix, grind, manipulate, measure, mix, sketch, demonstrate, execute, increase speed, improve, make, show dexterity, pace, produce |

| 5. Perform alone: modifies, responds as needed | Act habitually, advance confidently, control, excel, guide, manage, master, organize, perform quickly and more accurately |

| 6. Creates a new or original model | Adapt, alter, rearrange, reorganize, revise |

Modified from French D, Olrech N, Hale C, et al: Blended learning: an ongoing process for Internet integration, Victoria, Canada, 2003, Trafford Publishing.

Affective Domain

The patient’s attitudes and motivations influence his or her ability to learn. It is important to remember that, with patient education, timing is everything. Patients who have recently been given a poor prognosis or who are in pain are not in an optimal position to learn. Maslow suggested a hierarchy of needs, and he identified physiologic needs as the most basic of human needs, followed by safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization.3 Lower-level needs must first be satisfied before moving on to higher-level needs. For example, if a patient is dyspneic or in pain, he or she will probably not be receptive to learning the steps that are involved in cleaning a small-volume nebulizer. It is important for RTs to assess a patient’s readiness to learn by talking with the patient and his or her family and by listening to the patient’s concerns. It is important to develop a relationship of trust and to be empathetic with the patient.

1. Demonstrate genuine concern for yourself by using your oxygen therapy correctly.

2. Demonstrate a willingness to learn by being an active participant in the program.

Affective domain action verbs are included in Table 49-3.2

TABLE 49-3

Verbs for the Affective Domain

| Purpose | Example Verbs |

| 1. Receive: becoming aware of | Accept, acknowledge, alert, choose, give, attend, notice, perceive, tolerate, select |

| 2. Respond: interested in or doing something about something | Agree, assist with, aid, answer, assist, comply, conform, communicate, consent, label, obey, cooperate, follow, read, report, visit, volunteer, study |

| 3. Value: concerned about, developing an attitude | Adopt, assume, behave, choose, demonstrate, commit, desire, initiate, join, exhibit, express, prefer, seek, share |

| 4. Organize: arranging systematically, confirming | Adapt, adjust, arrange, classify, conceptualize, group, rank, validate, verify, strengthen, substantiate, corroborate, confirm |

| 5. Characterize: internalizing a set of values, championing | Demonstrate a change in lifestyle, discriminate, defend, influence, invite, listen, preach, qualify, question, serve, act upon, advocate, devote, expose, justify, support |

Modified from French D, Olrech N, Hale C, et al: Blended learning: an ongoing process for Internet integration, Victoria, Canada, 2003, Trafford Publishing.

Teaching Tips

Following is a list of time-honored suggestions for improving patient education:

• Address the patient’s immediate concerns first.

• Create an optimal learning environment. Teach in a quiet and relaxed setting.

• Have patients use as many of their senses as possible during their learning session. Whenever possible, include hearing, seeing, smelling, speaking, touching, and doing.

• Keep sessions short. If the material is complex, break it down into brief segments.

• Provide many opportunities for the patient to practice psychomotor skills.

• Be organized. People learn more quickly when they are presented with information that is well organized.

• Demonstrate enthusiasm for what you are doing. The learner can always sense your level of motivation.

• Evaluate in a nonthreatening manner, and provide helpful feedback. Use evaluation as a learning tool.

Teaching Children As Compared With Teaching Adults

Teaching children is often very different than teaching adults. Children are more motivated by external factors (e.g., prizes) as compared with adults, who tend to have internal motivating factors. This suggests that adults will learn quicker if they can easily see the intrinsic value of knowing more about their illness. Alternatively, children may need a more obvious reward system in place before learning can take place. They have no problem taking instruction from adults, because they are often dependent on such instruction. Adults, however, are more independent, and they do not like being dependent on others. This suggests that adults should be more involved in setting program goals and that they will readily learn skills that make them more independent. Other important issues related to differences between children and adult learners are listed in Box 49-1, and allocated time for teaching is given by age in Box 49-2.4

Health Education

Health promotion helps people change their lifestyles in a variety of settings, from the home or school to the workplace or the health care agency or institution. To be effective, health education must be combined with strategies for health promotion; the two are strongly linked. The American Association for Respiratory Care has created a statement for health promotion and disease prevention (Box 49-3).5

Although individuals must ultimately assume responsibility for their own health, promoting healthy behaviors through education is an important part of being an RT. In this capacity, the RT should serve as a role model for the public. Unless health care professionals model healthy behaviors, successful health outcomes cannot be expected from the public. To this end, the American Association for Respiratory Care has created a role-model statement to encourage RTs to set a positive example for the public (Box 49-4).6

1. Program participants must be actively engaged in the learning process.

2. Activities must incorporate the values and beliefs of the learner. Familial, cultural, societal, and economic factors must be considered.

3. The role of the health educator is to facilitate behavioral change. Thus, the learning process should be approached together by both the learner and the educator.

4. The process of predisposing an individual toward improved health as well as enabling and reinforcing health attitudes requires effort, which will only reap results over time.

5. The health care educator must be willing to listen nonjudgmentally to the concerns of the learners. Empathy and understanding are necessary to foster a trusting relationship.

6. The level of the learners’ self-esteem and self-concept may either enhance or inhibit their ability to make decisions about their own health. The health care educator should be willing to provide emotional support as necessary.

7. The health care educator’s personal characteristics have a direct impact on the outcome of the educational program. Generally, successful outcomes occur as a result of a confident and professional approach.

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

In 2008, the United States spent $2.3 trillion on health care.7 Four of the five major causes of death in the United States are heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease (stroke), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These diseases have four central causes that, in large part, are preventable: tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use.8

With this in mind, a quote from Rufus Howe is appropriate: “What a rare privilege it is to be in a position to improve the lives of others.”9

Recent efforts such as Healthy People 2010 have attempted to place the focus on the health of the population rather than on that of the individual.10 The two broad goals of this plan are as follows: (1) to increase the quality and years of healthy life; and (2) to eliminate health disparities. These goals encompass the essential elements of health promotion and disease prevention, which are the prevention of premature death, disease, and disability as well as the improvement of the quality of life.

The recognition that allied health professionals such as RTs play vital roles in these activities prompted professional organizations to develop policy statements about health promotion and disease prevention. The American Association for Respiratory Care policy statement appears in Box 49-5.5

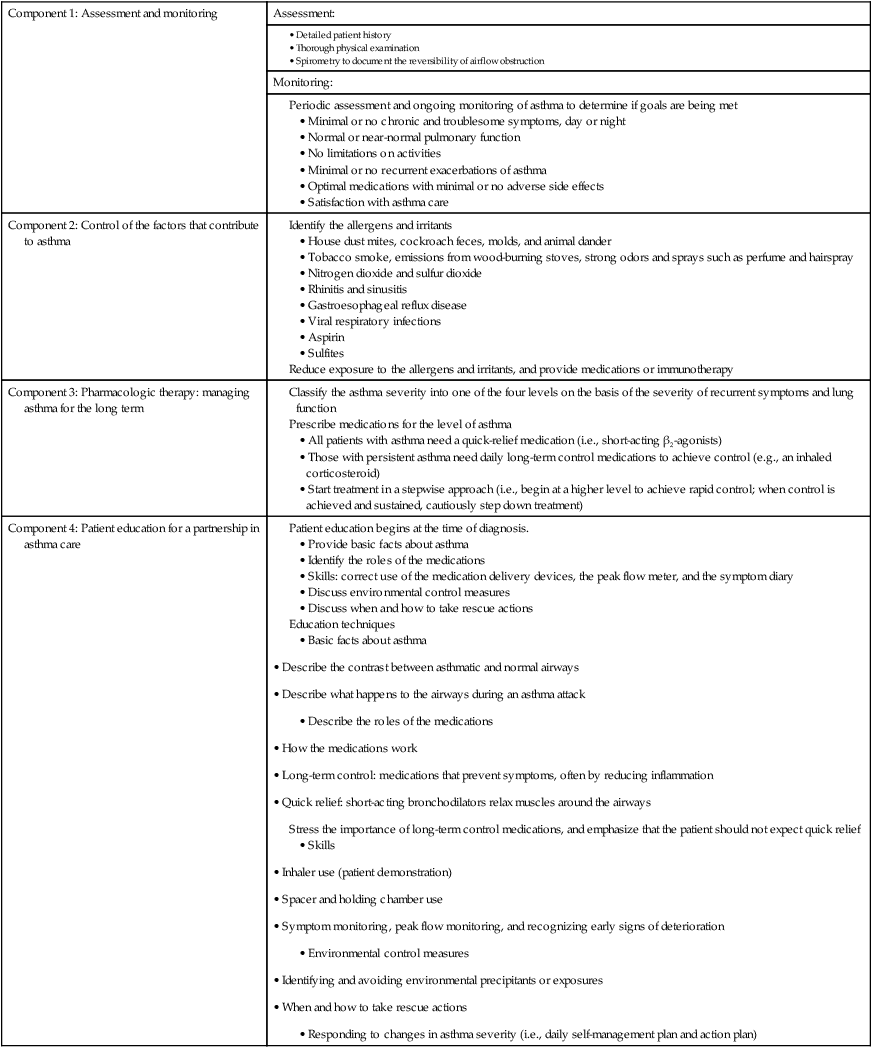

RTs can take an active role in the development of educational materials to assist both the public and other health professionals with regard to health promotion activities. Many medical manufacturers have also developed asthma education kits of various types that include peak flow meters, spacers, and educational materials. These kits are generally developed with input from the medical community and in particular from RTs. An example of an asthma program is given in Table 49-4.11 Respiratory care educational programs need to be diligent when incorporating health promotion and disease prevention activities into all learning domains as part of their curricula.

TABLE 49-4

Components of an Asthma Disease Management Program

| Component 1: Assessment and monitoring | Assessment: |

Identify the allergens and irritants

• House dust mites, cockroach feces, molds, and animal dander

• Tobacco smoke, emissions from wood-burning stoves, strong odors and sprays such as perfume and hairspray

• Nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide

• Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Reduce exposure to the allergens and irritants, and provide medications or immunotherapy

Classify the asthma severity into one of the four levels on the basis of the severity of recurrent symptoms and lung function

Prescribe medications for the level of asthma

• All patients with asthma need a quick-relief medication (i.e., short-acting β2-agonists)

• Those with persistent asthma need daily long-term control medications to achieve control (e.g., an inhaled corticosteroid)

• Start treatment in a stepwise approach (i.e., begin at a higher level to achieve rapid control; when control is achieved and sustained, cautiously step down treatment)

Patient education begins at the time of diagnosis.

• Provide basic facts about asthma

• Identify the roles of the medications

• Skills: correct use of the medication delivery devices, the peak flow meter, and the symptom diary

Stress the importance of long-term control medications, and emphasize that the patient should not expect quick relief

• Inhaler use (patient demonstration)

• Spacer and holding chamber use

• Symptom monitoring, peak flow monitoring, and recognizing early signs of deterioration

• Environmental control measures

• Responding to changes in asthma severity (i.e., daily self-management plan and action plan)

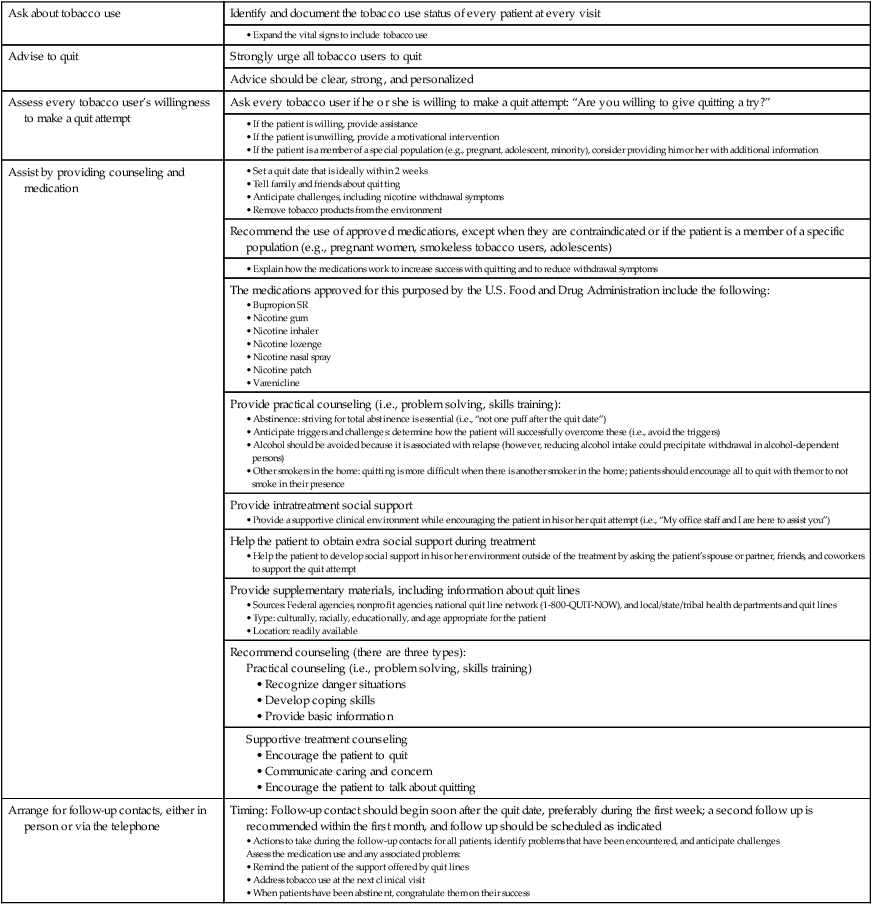

Another specific area of health promotion that receives much attention in both hospital and public health settings is nicotine intervention. Nicotine intervention is a progressive, comprehensive program that incorporates a series of steps from risk identification to maintenance support. Seventy percent of smokers report that they would like to quit but cannot.12 Smoking cessation aids such as nicotine gum and nicotine patches are now available over the counter. Nicotine replacement therapy combined with behavioral therapy is often more effective for tobacco cessation. Varenicline tartrate (Chantix) received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for patients who are attempting smoking cessation.13 It is not a nicotine replacement medication; rather, it acts at the sites in the brain that are affected by nicotine.

National, state, and local agencies such as the American Cancer Society, the American Lung Association, and the American Heart Association offer educational materials and behavioral counseling. The educational materials that these agencies offer are available via mail, telephone, and the Internet. In 2004, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services established a nationwide toll-free number (800-QUIT-NOW [800-784-8669]) to serve as an access point for smokers who are seeking assistance with quitting. Components of the Office of Surgeon General’s tobacco cessation program are included in Tables 49-5 and 49-6.14

TABLE 49-5

The “5 As” Model for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence as a Chronic Disease

| Ask about tobacco use | Identify and document the tobacco use status of every patient at every visit |

| Advise to quit | Strongly urge all tobacco users to quit |

| Advice should be clear, strong, and personalized | |

| Assess every tobacco user’s willingness to make a quit attempt | Ask every tobacco user if he or she is willing to make a quit attempt: “Are you willing to give quitting a try?” |

| Assist by providing counseling and medication | |

| Recommend the use of approved medications, except when they are contraindicated or if the patient is a member of a specific population (e.g., pregnant women, smokeless tobacco users, adolescents) | |

| The medications approved for this purposed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include the following: | |

| Provide practical counseling (i.e., problem solving, skills training):

• Abstinence: striving for total abstinence is essential (i.e., “not one puff after the quit date”) • Anticipate triggers and challenges: determine how the patient will successfully overcome these (i.e., avoid the triggers) • Alcohol should be avoided because it is associated with relapse (however, reducing alcohol intake could precipitate withdrawal in alcohol-dependent persons) • Other smokers in the home: quitting is more difficult when there is another smoker in the home; patients should encourage all to quit with them or to not smoke in their presence |

|

| Provide intratreatment social support | |

| Help the patient to obtain extra social support during treatment | |

| Provide supplementary materials, including information about quit lines | |

| Recommend counseling (there are three types): | |

| Arrange for follow-up contacts, either in person or via the telephone | Timing: Follow-up contact should begin soon after the quit date, preferably during the first week; a second follow up is recommended within the first month, and follow up should be scheduled as indicated

• Actions to take during the follow-up contacts: for all patients, identify problems that have been encountered, and anticipate challenges Assess the medication use and any associated problems: |

TABLE 49-6

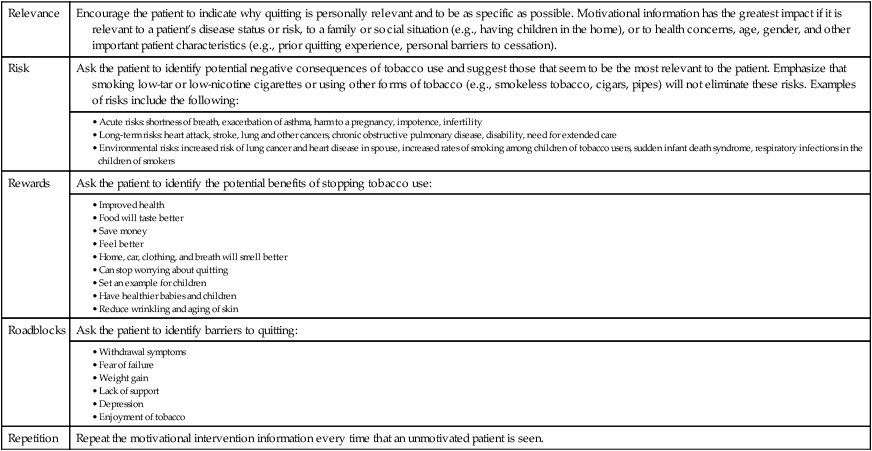

Components of a Tobacco Education Program for Those Who Are Unwilling to Quit

Enhancing Motivation to Quit Tobacco: The “5 Rs”

| Relevance | Encourage the patient to indicate why quitting is personally relevant and to be as specific as possible. Motivational information has the greatest impact if it is relevant to a patient’s disease status or risk, to a family or social situation (e.g., having children in the home), or to health concerns, age, gender, and other important patient characteristics (e.g., prior quitting experience, personal barriers to cessation). |

| Risk | Ask the patient to identify potential negative consequences of tobacco use and suggest those that seem to be the most relevant to the patient. Emphasize that smoking low-tar or low-nicotine cigarettes or using other forms of tobacco (e.g., smokeless tobacco, cigars, pipes) will not eliminate these risks. Examples of risks include the following: |

|

• Acute risks: shortness of breath, exacerbation of asthma, harm to a pregnancy, impotence, infertility • Long-term risks: heart attack, stroke, lung and other cancers, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, disability, need for extended care • Environmental risks: increased risk of lung cancer and heart disease in spouse, increased rates of smoking among children of tobacco users, sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory infections in the children of smokers |

|

| Rewards | Ask the patient to identify the potential benefits of stopping tobacco use: |

| Roadblocks | Ask the patient to identify barriers to quitting: |

| Repetition | Repeat the motivational intervention information every time that an unmotivated patient is seen. |

Disease Management

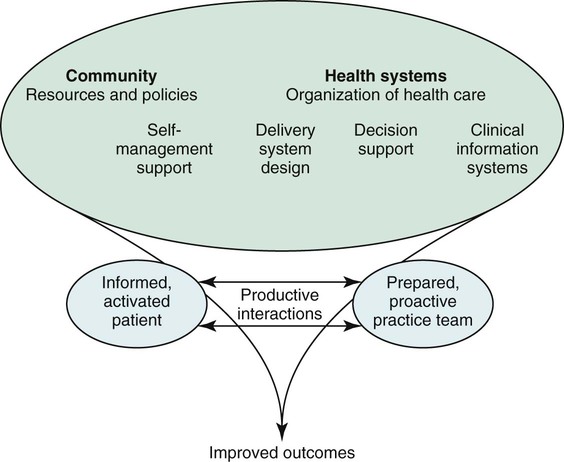

The most recent data show that more than 145 million people—which is approximately half of all Americans—live with chronic disease.15 Half of those with chronic illness have more than one chronic condition or comorbidity. These chronic diseases are extremely expensive and lead to unnecessary admissions. Chronic care models have been used since the 1990s. A chronic care model is patient centered; it encourages multidisciplinary focus on self-management and continuous quality control. Wagner presented the chronic care model that is illustrated in Figure 49-1.16

Wagner explains the model as follows: “[P]atients and families who struggle with chronic illness require planned, regular interactions with their caregivers, with a focus on function and prevention of exacerbations. This interaction includes systematic assessments, attention to treatment guidelines, and behaviorally sophisticated support for the patient’s role as a self manager. These interactions must be linked through time by clinically relevant information and continuing follow-up.”16

As with disease management, which is a method of applying the best health care practices to a population with a chronic illness one person at a time,9 the goals of this type of program include improving the health of the person, improving patient satisfaction, reducing mortality, improving quality of life, and eliminating unnecessary medical treatment to reduce the cost of health care.9 There is no one definition of disease management. However, the Care Continuum Alliance defines disease management as a coordinated system of interventions for people who have conditions that require significant self-care.17 Disease management is measured by its impact on costs, clinical outcomes, and quality of life. The programs have similar components, including a coordinated comprehensive interdisciplinary care team with a process for measuring improvement. Health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and the federal government all pay for disease management programs.9 Most programs have the following attributes:

• The provision of interdisciplinary comprehensive care (i.e., health promotion, prevention, and acute care)

• A population-identification process (for a specific disease or condition)

• The use of evidence-based guidelines, protocols, and pathways

• Collaborative and coordinated components of care

• Active patient self-management and education (e.g., empowerment, behavior modification)

• The use of information technology to create a feedback loop

Implications for the Respiratory Therapist

Home

Home health care continues to be a rapidly growing segment of the health care industry. It has been proved repeatedly to be more cost-effective than hospital care. RTs can perform a wide variety of services in the patient’s home, including oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation on either a temporary or long-term basis. Generally the focus is on tertiary prevention (i.e., preventing further decline). Patient education is of primary importance in the home in so that the patient may become as self-reliant as possible (see Chapters 50 and 51).