Patient-controlled analgesia

Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia

Advantages

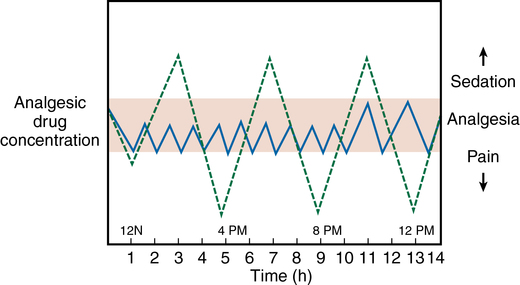

The main advantage of IV PCA with opioids is that it is “patient-controlled.” Traditional intermittent nurse-administered parenteral analgesia is inherently labor intensive and fraught with problems. Patients receive a “scheduled” or an “as-needed” dose of an analgesic drug, one that is targeted for a broad patient population, with little thought given to the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug in an individual patient. Doses of analgesic drugs are relatively large, sometimes exceeding the minimal effective dose, to achieve a more sustained effect. The time to redosing is often prolonged, resulting in low serum drug concentrations and the recurrence of pain. The “as-needed” administration of analgesic drugs is an even less favorable regimen because patients often wait until their pain is significant before calling the nursing staff, nurses must be able to respond to the call, the analgesic drug must be obtained from the pharmacy or the medication-dispensing device, and then, after the elapse of some time, patients receive their pain medication. With both regimens, patients can experience “peaks” of supratherapeutic analgesia, which can increase the risk of complications such as respiratory depression, nausea, and emesis, followed by “valleys” of low serum opioid levels, during which patients experience “breakthrough” pain. These subtherapeutic levels, with their associated inadequate analgesia, may limit patients’ progress, as evidenced by inadequate pulmonary hygiene, an unwillingness to get out of bed, and refusal to participate in postoperative rehabilitation. In a study of patients administered opioid analgesic agents intramuscularly every 3 to 4 h, the subsequent serum drug concentration met (or exceeded) the minimal analgesic concentration only 35% of the time (Figure 211-1). The other 65% of the time, the dose was inadequate for the patient to achieve adequate analgesia, which, in turn, was associated with adverse perioperative outcomes and patient dissatisfaction. Because the dose of analgesic agent and lockout interval are better individualized, and because it eliminates a second person as a decision maker (i.e., the nurse), IV PCA maintains more effective serum analgesic drug concentrations, minimizes adverse effects, and improves patient satisfaction. Other reported advantages of IV PCA are listed in Box 211-1.

Choice of opioids

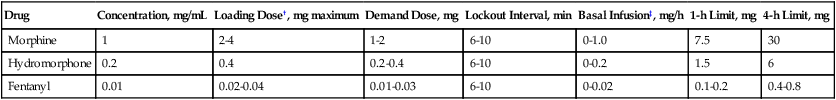

Morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl are the opioids commonly administered via IV PCA. Meperidine, in the past an often used agent, is less frequently used because of the potential adverse effects (i.e., seizures) associated with its active metabolite, normeperidine, and the recognition of better alternative agents. (Table 211-1).

Table 211-1

Suggested Dosing Regimens for Opioid-Naïve Patients* Receiving Opioids via Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia

| Drug | Concentration, mg/mL | Loading Dose†, mg maximum | Demand Dose, mg | Lockout Interval, min | Basal Infusion‡, mg/h | 1-h Limit, mg | 4-h Limit, mg |

| Morphine | 1 | 2-4 | 1-2 | 6-10 | 0-1.0 | 7.5 | 30 |

| Hydromorphone | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2-0.4 | 6-10 | 0-0.2 | 1.5 | 6 |

| Fentanyl | 0.01 | 0.02-0.04 | 0.01-0.03 | 6-10 | 0-0.02 | 0.1-0.2 | 0.4-0.8 |

*Elderly patients (>65 y) and patients on chronic opioids may need adjustment of these guidelines.

†The loading dose is given as a bolus every 5 min until the patient is comfortable and then the patient-controlled analgesia is started.

‡Most practitioners do not recommend a continuous infusion for most patients.

Adverse effects and outcomes

IV PCA with opioids is not without side effects and adverse outcomes (Box 211-2). Nausea, vomiting, and pruritus are not uncommon, and excessive somnolence has been observed. In a group of patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty and received an IV PCA for postoperative analgesia, investigators observed that, on postoperative day 2, more than 50% of patients experienced episodes of desaturation (SpO2 < 90%) and one patient experienced a respiratory arrest. To improve the safety of IV PCA, many hospitals have guidelines that recommend staff members have regular interaction with patients and measure and document the patient’s pain scores (using a metric such as numeric or visual analog scores), respiratory rate, O2 saturation via pulse oximetry, state of arousal, and level of sedation. In opioid-related respiratory depression, O2 desaturation is a delayed observation. With the advancement of technology and recent more widespread availability, end-tidal CO2 monitors are used more often. As these devices become more accepted in clinical practice, it is hoped that IV PCA will become a safer modality for analgesic administration.