Patient consent

Introduction

The General Medical Council (GMC) requires written consent to be obtained in the following circumstances (GMC 2008):1

• The investigation or treatment is complex or involves significant risks

• There may be significant consequences for the patient’s employment, or social or personal life

• Providing clinical care is not the primary purpose of the investigation or treatment

• The treatment is part of a research programme or is an innovative treatment designed specifically for their benefit.

The three components of consent are: voluntariness, information and capacity. For consent to be valid consent must be voluntarily given, the patient must have information regarding the treatment concerned and must be competent to do so.

Voluntariness

It is useful to create a suitable environment to facilitate voluntary consent taking. It is good practice to take consent prior to the patient entering the operating room, as this environment places the patient under pressure and may invalidate consent.2 Suitable environments, which allow privacy and sufficient time for the patient to understand the information provided and to ask questions, include outpatient clinic and ward quiet rooms.

Patients may occasionally withdraw consent during a procedure. Should this occur, the doctor should immediately stop the procedure (even temporarily) and explore the patient’s concerns. Medication or pain may affect the patient’s capacity at this time. However, if the patient wishes the procedure to end and there is no possibility of immediate harm, the patient’s wishes should be accepted as a withdrawal of consent and the procedure halted.2

Information

Who?

The person providing care should take consent for the procedure. If this responsibility is delegated, the individual taking consent should have sufficient knowledge of the procedure.3 Confirmation of consent, done at the time of the procedure, remains the responsibility of the doctor performing the procedure.2

When?

For non-urgent procedures consent should be taken at least 24 hours prior to the procedure to allow the patient to consider the options available to them and change their mind if they wish to.4 There is no specific time limit on consent as long as the information provided to the patient has not changed with the passage of time.

What?

The GMC recommends the following information be provided to the patients prior to any procedure (GMC 2008):1

• The diagnosis and its prognosis

• Treatment or management options for the condition, including the option not to treat

• The purpose of any proposed investigation or treatment and what it will involve

• The potential benefits, risks and burdens, and the likelihood of success, for each option; this should include information, if available, about whether the benefits or risks are affected by which organization or doctor has chosen to provide care

• Whether a proposed investigation or treatment is part of a research programme or is an innovative treatment designed specifically for their benefit

• The people who will be mainly responsible for and involved in their care, what their roles are, and to what extent students may be involved

• Their right to refuse to take part in teaching or research

• Their right to seek a second opinion

• Any bills they will have to pay

• Any conflicts of interest that you, or your organization, may have

• Any treatments that you believe have greater potential benefit for the patient than those you or your organization can offer.

The GMC advises that doctors discuss these matters with patients, encourage them to ask questions, listen to their concerns and ask for and respect their views.

Information literature should be clear and concise and designed for patients.2 Many radiologists make use of patient information booklets compiled by professional societies such as the RCR, CIRSE and BSIR, which go some way to providing standardized complication rates for common procedures.

Capacity

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 of England is underpinned by five statutory principles:

• All persons are assumed to have capacity unless the contrary is demonstrated

• All practicable steps must be taken to assist the person in making a decision

• The person should not be considered to lack capacity if they choose to make an unwise decision

• Any decision made or act done under this Act on behalf of a person lacking capacity should be in that person’s best interests

• Any act done or decision made should be the least restrictive possible that would ensure a good outcome.

The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act has similar requirements and includes an expectation that interested parties should be consulted and that incapacitated people are encouraged to use existing skills.

Assessment of capacity

In order to undertake a capacity assessment, a two-stage test of capacity should occur.

1. Does the person have an impairment (of mind or brain) or is there a disturbance affecting the way their mind or brain works?

2. If so, does the impairment mean that the person is unable to make the decision at the time needed?

An assessment of capacity need only be undertaken if there is a doubt about the person’s mental functioning at the time.

In order to assess capacity, the following need to be evaluated (Mental Capacity Act 2005: Code of Practice):5

• Does the person have a general understanding of what decision they need to make and why they need to make it?

• Does the person have a general understanding of the likely consequences of making or not making this decision?

• Is the person able to understand, retain, use and weigh up the information relevant to this decision?

• Can the person communicate their decision (by talking, using sign language or other means)? Would the services of a professional (such as a speech and language therapist) be helpful?

• And in more complex or serious decisions: Is there a need for a more thorough assessment (perhaps by involving another professional expert)?

Patients are deemed to lack capacity if they cannot:

• Understand information about the decision to be made (the Act calls this ‘relevant information’)

• Retain that information in their mind

• Use or weigh that information as part of the decision-making process, or

• Communicate their decision (by talking, using sign language or any other means).

Only one of the above needs to be absent for the person to lack capacity, although more than one is often present.

Supporting patients to make decisions

Doctors may encounter patients who choose not to undergo treatments or procedures offered to them even though this may result in significant morbidity or death. Patients have the right to make unwise decisions and doctors should guard against coercion.6

In these cases all discussions with the patient, a comprehensive and contemporaneous documentation of the capacity assessment and consent procedure should be entered into the patient’s medical notes. The RCR recommends that in these cases the notes are witnessed by a third party.2 If this patient later loses the capacity to consent to a procedure, clinicians must not then perform the intervention in the patient’s best interests: under the Mental Capacity Act this would be considered a criminal offence of ill-treatment.

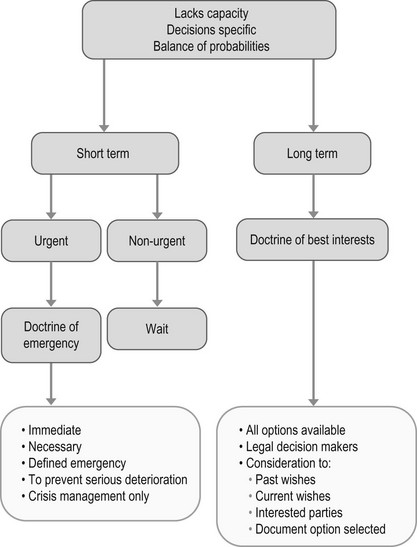

Acting for patients who lack capacity

• Within the health and welfare LPA agreement there is an explicit declaration made determining whether the attorney is empowered to give or refuse consent for treatments specifically deemed to be life-sustaining so clarification should be sought.

• Separate Lasting Power of Attorney arrangements can also be made for property and financial decisions but these alone do not confer any power for the attorney to make health-related decisions on behalf of the patient.

• Similarly, any older Enduring Power of Attorney arrangements still in force (made pre 2007) allow only proxy financial, not health or welfare, decisions to be made.

• Scottish law makes no distinction between differing powers of attorney.

When acting in a person’s best interests, clinicians should do so in the least restrictive manner possible. If less invasive alternatives exist to the preferred intervention, then these should be attempted first.

Documenting assessment of capacity

• The details of the intended intervention

• The specific reason the patient has been deemed to lack capacity and how this judgement was reached (as above)

• Attempts that have been made to assist the patient to make his/her own decision and why these were unsuccessful

• The likelihood that the patient may regain capacity and the reason the intervention needs to be performed before this can occur

• The steps taken to establish the patient’s previously expressed wishes including the names of the family members consulted

• The names and designation of clinical colleagues consulted in deciding on the proposed intervention

• The name of the clinician responsible for performing the procedure

• The name and designation of any clinician who has provided a second opinion.

Shared decision-making

As part of the Liberating the NHS White paper published in May 2011, there is an increasing requirement of clinicians to involve patients in decisions about their care. ‘No decision about me without me’ requires clinicians to agree on treatment plans in partnership with their patients. There is a growing expectation from the public for doctors to provide sufficient information for patients to allow them to make their own decisions. This is particularly important in procedures where there is lack of consensus and there is a perceived variance of risk between the clinician and the patient (Fig. 20.1).

References

1. General Medical Council. Consent: Patients and Doctors making decisions together. http://www. gmc-uk. org/guidance/ethical_guidance/consent_guidance_index. asp, 2008.

2. The Royal College of Radiologists, Standards for patient consent particular to radiology. 2nd ed. The Royal College of Radiologists, London, 2012. http://www. rcr. ac. uk/publications. aspx?PageID=310&PublicationID=372

3. The Medical Protection Society, Consent to Medical Treatment in the UK. MPS 2011; . http://www. medicalprotection. org/mps-guide-to-consent. pdf

4. O’Dwyer, HM, Lyon, SM, Fotheringham, T, et al. Informed consent for interventional radiology procedures: a survey detailing current European practice. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2003; 26:428–433.

5. Mental Capacity Act. Code of practice. www. publicguardian. gov. uk/mca/code-of-practice. htm, 2005.