33 Parkinson Disease

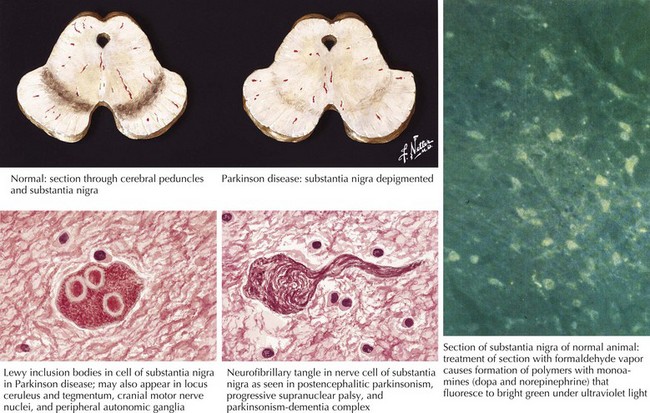

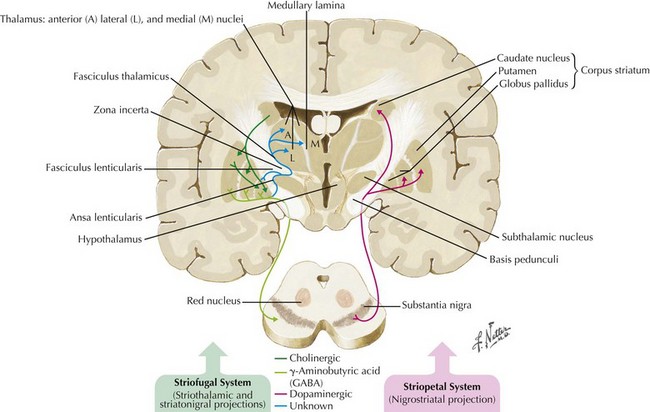

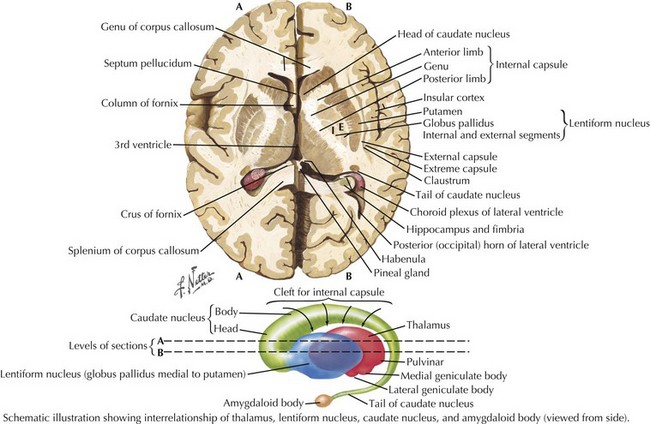

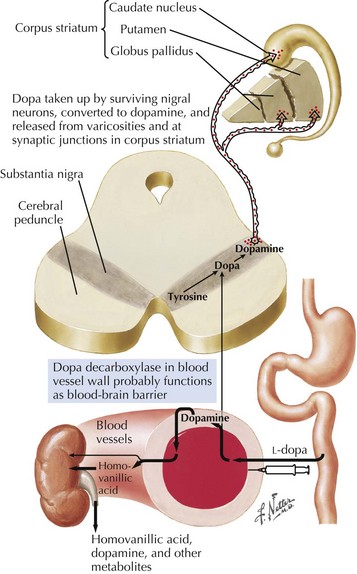

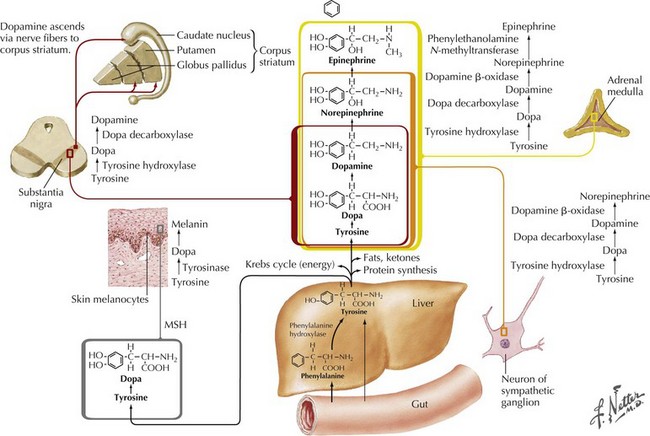

In 1817, James Parkinson made the seminal observations on this disorder defining a specific neurodegenerative illness characterized by bradykinesia, resting tremor, cogwheel rigidity, and postural reflex impairment. Parkinson disease (PD) has a relatively stereotyped clinical presentation that now bears the name of this early 19th-century physician. PD is one of the most common neurologic disorders worldwide. It affects at least 1,500,000 persons within the United States. Its incidence typically peaks in the sixth decade; however, one can see classic clinical cases with onset as early as the fourth decade. On occasion, medication-induced Parkinson disease may also occur in early middle-aged individuals. In contrast, PD sometimes presents well into the late eighth or even the ninth decade. Usually the patient’s clinical status progresses from a relatively modest limitation at diagnosis to an ever-increasing disability over 10 to 20 years in many but not all patients. The primary neuropathologic features are loss of pigmented dopaminergic neurons mainly in the substantia nigra (SN) and the presence of Lewy bodies—eosinophilic, cytoplasmic inclusions found within the pigmented neurons (Fig. 33-1). These neurons’ primary projection is to the striatum, for example, the putamen and caudate. Dopamine is released primarily from these striatal cells. From here dopamine neurotransmission sequentially is directed through the globus pallidus, the subthalamic nucleus, to the thalamus per se, and then to the primary motor cortex (Figs. 33-2 and 33-3).

Etiology

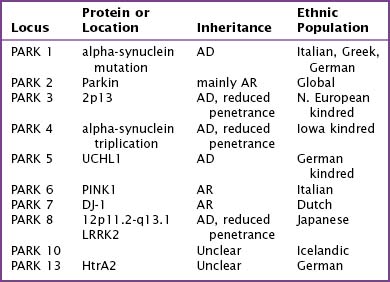

Fifteen percent of Parkinson patients have a family history of PD; a small percentage of these individuals have at least three affected generations. It is unknown whether the clinical picture results from a defective gene per se, a shared environmental insult, or both. Currently there are several causative genes identified that are specific to young-onset PD. Although these well-identified PD genes are pathogenic in only a very small minority of individuals, their biochemical signatures are providing extraordinary insight into the molecular pathology of this disease. The currently identified genes are listed in Table 33-1.

Genes for Parkinson Disease

Alpha-Synuclein

The discovery that mutant AS could cause PD quickly led to the discovery that AS also served as the principal component of Lewy bodies. These are proteinaceous cytoplasmic inclusions specifically found in the brains of PD patients; however, even today, the exact role of Lewy bodies is still unknown (see Fig. 33-1). The confirmation that triplication of the AS gene and the subsequent elevated protein levels (in the CSF) could cause PD has greatly strengthened the hypothesis that accumulation of protein is a fundamental event in the pathogenesis of PD.

Pathology/Pathophysiology

The pathologic sites responsible for the parkinsonian disorders reside in a group of brain gray matter structures known as the extrapyramidal system or basal ganglia (Fig. 33-2). These include striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), globus pallidus interna and externa, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra pars reticulate and pars compacta, and the ventral nuclei of the thalamus.

Degeneration of the substantia nigra (SN) pars compacta is the pathologic hallmark of PD (Figs. 33-2 and 33-4). Neurons within the SN per se synthesize the neurotransmitter dopamine. These cells contain a dark pigment called neuromelanin. Parkinson symptoms develop when approximately 60% of these cells die. Concomitantly, direct inspection of the SN in PD demonstrates an abnormal pallor when compared with that characteristically seen with the normal hyperpigmented melanin-containing cells.

Clinical Presentation

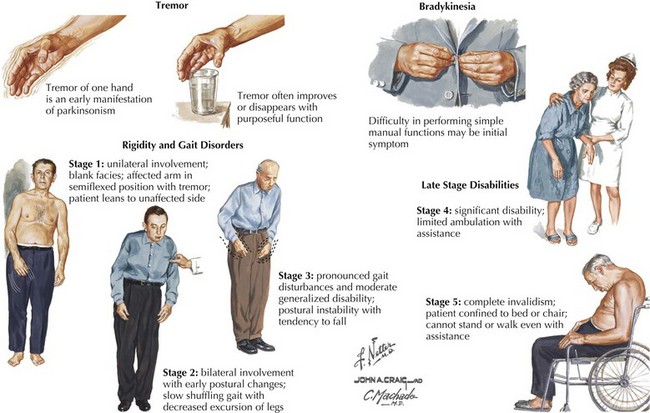

The four primary signs of PD are bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, and gait disturbance (Fig. 33-5). The primary criteria for a diagnosis of PD require that the patient’s neurologic examination demonstrate at least two of these four features. There are certain additional features very suggestive of idiopathic PD. These include an asymmetric or unilateral onset and a clear response to levodopa treatment. Importantly from the point of differential diagnosis, neither of these features occurs in some of the atypical parkinsonism syndromes.

Typically PD progresses in stages (Fig. 33-5). There are two commonly utilized rating scales to measure the degree of disability that these patients manifest: (1) UPDRS (Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale) and (2) Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale (Box 33-1).

Box 33-1 Parkinson Disease Rating Scales

Psychiatric and cognitive symptomatology also frequently accompany or even precede the diagnosis of PD in some patients: about 40% suffer a major depression that may precede the diagnosis of the movement disorder; anxiety also occurs in up to 40% of patients. Later on in PD, hallucinations (visual, most likely nonthreatening), psychosis, and vivid nocturnal dreams are common. Cognitive dysfunction is typically a later manifestation. Clinically, it has the characteristics of a subcortical dementia (Chapter 18).

The clinical course or temporal profile of PD is quite variable. However, it usually progresses slowly and inexorably (Fig. 33-5). Typically, the illness begins unilaterally with focal tremor or difficulty using one limb. Eventually, the symptoms become more generalized and occur on the contralateral side, interfering with activities of daily living. Several secondary signs of parkinsonism also develop as previously noted.

Early on, the neurologic clinician must maintain a level of alertness for the presence of certain other clinical characteristics that serve as “red flags” suggesting other non-Parkinson movement disorders. These are known as the “Parkinson plus” syndromes, including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and multiple-system atrophy (MSA) (see Box 33-3).

If possible, it is useful to exclude these early in the disease course as they may change the treatment and prognosis. These are considered in detail in Chapter 34.

Differential Diagnoses

When Parkinson-like findings are found in the face of other identifiable neurologic disorders, a primary diagnosis of PD should not be entertained. These include stroke, head injury, neuroleptic exposure, hydrocephalus, encephalitis, or brain tumor. The vast majority of PD patients present with at least two of the following classic findings, namely, bradykinesia; rigidity; tremor; and a petit pas, festinating gait disorder. When one only sees a single example of these physical changes, the patient may have early PD especially if associated with either seborrhea or anosmia. A certain set of clinical findings, such as the presence of supranuclear gaze palsy, must make one immediately consider other nontreatable movement disorders that are easily confused early on in these illnesses with PD (Box 33-2). Otherwise, there is a relatively limited set of conditions to consider in the evaluation of such individuals (Box 33-3). These include essential tremor, secondary, atypical and familial parkinsonism, and other rare causes of parkinsonism.

Box 33-2 Exclusion Criteria for Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease

Box 33-3 Differential Diagnoses of Parkinson Disease

Secondary Causes of Parkinsonism

Medications

Dopamine receptor-blocking agents used in psychiatry and for gastrointestinal symptoms are the most common drugs causing parkinsonism (Table 33-2). In the hospital, one may see patients who have newly developed parkinsonism after a relatively short course of symptomatic gastrointestinal medications such as metoclopramide. Of patients taking neuroleptic agents on a long-term basis, ~15% develop parkinsonism. Recovery following withdrawal of the offending agent may take weeks to months. If antiparkinsonian medication is required in these patients, anticholinergics are the drugs of choice.

| Generic | Trade Name |

|---|---|

| Acetophenazine | Tindal |

| Amoxapine | Asendin |

| Chlorpromazine | Thorazine |

| Fluphenazine | Permitil, Prolixin |

| Haloperidol | Haldol |

| Loxapine | Loxitane, Daxolin |

| Mesoridazine | Serentil |

| Metoclopramide | Reglan |

| Molindone | Lidone, Moban |

| Perphenazine | Trilafon or Triavil |

| Piperacetazine | Quide |

| Prochlorperazine | Compazine, Combid |

| Promazine | Sparine |

| Promethazine | Phenergan |

| Thiethylperazine | Torecan |

| Thioridazine | Mellaril |

| Thiothixene | Navane |

| Trifluoperazine | Stelazine |

| Triflupromazine | Vesprin |

| Trimeprazine | Temaril |

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus

This must also be considered in the PD differential diagnosis. Normal-pressure hydrocephalus also typically presents with a gait disorder; however, it is somewhat different than that of idiopathic PD (see Chapter 32, Fig. 32-2). Typically slowness of gait is the initial symptom; characteristically this is a “magnetic” mildly wide-based finding likened to walking in cement. Cognitive decline may appear earlier in this syndrome than in PD, and “unwitting incontinence” may follow. It is important to recognize this relatively uncommon disorder early on as it is eminently treatable.

Other Disorders

Characterized by a poor levodopa response, arteriosclerotic parkinsonism (i.e., lower body parkinsonism) is the PD variant most likely to be associated with head CT or MRI abnormalities. They are primarily visible as periventricular white matter changes. Mass lesions, such as tumors, are exceedingly rare causes of parkinsonism. Multiple head trauma, as seen in boxers, can cause parkinsonism. Degenerative diseases causing parkinsonism are best classified by the type of abnormal degree of neurochemical deposition (Table 33-3).

| Alpha-synuclein Deposition | Tau Deposition | Polyglutamine Tract Deposition |

|---|---|---|

SCA indicates spinocerebellar atrophy.

Atypical Parkinsonism

Atypical parkinsonian syndromes or “Parkinson plus syndrome” (Chapter 34) are chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by rapidly evolving parkinsonism in association with other signs of neurologic dysfunction not found within the spectrum of idiopathic Parkinson disease (PD) (Box 33-2). The presence of atypical signs on examination, sometimes called “red flags” (supranuclear gaze palsy, corticospinal pathway involvement, cerebellar signs, early autonomic dysfunction or dementia) with rapidly progressive course and minimal response to dopaminergic medications should trigger the clinician to look for atypical parkinsonism such as PSP, CBD, MSA or DLBD.

Familial Parkinsonism

A well-defined genetic component is present in a minority of PD patients even though most individuals developing classical parkinsonism have no specific etiology identified. Mutations in five causative genes (Table 33-1) together account for 2–3% of all patients with classical parkinsonism. These include alpha-synuclein (SNCA), parkin, PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), DJ-1, and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2). These patients are often clinically indistinguishable from others with idiopathic PD. Although the individual clinical course cannot be predicted, overall, many cases of genetic PD will progress more slowly and respond better to treatment than patients without mutations. Genetic testing frequently yields inconclusive results, is expensive, and does not have a current indication in the vast majority of PD patients. DNA testing is rarely indicated in suspected PD patients. It may be occasionally useful for diagnostic purposes but only after careful consideration in selected cases at specialty centers.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Key diagnostic elements are the presence of two of the four cardinal signs: bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, and gait problems (Fig. 33-5). However, it is unusual for a patient to present initially with the full-blown disease, and characteristic signs may not be present. Frequently, the patient may first become aware of a nonspecific fatigue in previously well-performed activities of daily living primarily affecting motor function. They may note a diminished reserve for distance demands. Clinical reexamination in several-month intervals is often needed to confirm a diagnosis of PD. Signs of another degenerative process sometimes become evident, interdicting the earlier diagnostic suspicion.

Once a specific PD diagnosis is confirmed, it is useful to qualitatively measure (Box 33-1) the disease severity. This allows the treating physician to establish a pretreatment clinical baseline. This will serve as a reference for future comparisons.

Treatment

Pharmacologic therapy for PD consists of five types of medication (Box 33-4). There is no simple approach to treating PD; guidelines depend on functional impairment and response to therapy.

Box 33-4 Pharmacologic Therapy for Parkinson Disease

COMT, Catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Dopaminergic

Levodopa

Levodopa (LD) with carbidopa is the most commonly used, most potent antiparkinsonian medication and is equally beneficial for all symptoms. Levodopa is the immediate natural precursor of dopamine and is converted to dopamine by the enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) (Fig. 33-6). Initially, levodopa was associated with a high rate of side effects, particularly nausea and vomiting, because of its ability to stimulate peripheral, non–central nervous system dopamine receptors. The addition of the decarboxylase inhibitor carbidopa decreased the incidence of the peripheral side effect, permitted more levodopa to cross the blood–brain barrier, and consequently allowed a reduction of the total levodopa dose. Carbidopa-levodopa is available in immediate-release form as tablets (Sinemet) or sublingual pills (Parcopa) and controlled-release formulations (Sinemet CR).

Dopaminergic Agonists

DAs are used mainly early in the illness because they reduce the need for levodopa. Although not as effective as levodopa, DAs often provide satisfactory relief of mild symptoms. In those instances when severe symptoms interfere with the patient’s social or occupational activities, early symptomatic treatment with carbidopa-levodopa, later combined with a DA, may be necessary. Commonly utilized preparations include pramipexole, ropinirole, bromocriptine, and pergolide (Box 33-5). Pergolide had been recently taken off the market because of potential heart valvular damage. Impulse control disorders or dysfunctional behaviors are problems that have been increasingly recognized with dopaminergic agonists but that occur much less commonly with levodopa. These disorders include hypersexuality, compulsive gambling, meaningless and repetitive activities (punding), hypomanic states, and addictive overuse of levodopa.

Box 33-5 Advantages and Disadvantages of Dopamine Agonists

Disadvantages

Bonuccelli U, Ceravolo R. The safety of dopamine agonists in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008 Mar;7(2):111-127.

Ho BL, Lieu AS, Hsu CY. Hemiparkinsonism secondary to an infiltrative astrocytoma. Neurologist. 2008 Jul;14(4):258-261.

LeWitt PA. Levodopa for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2468-2476. An excellent overall discussion of the current status of first-line medical therapy

McGoon DC. The Parkinson’s Handbook. New York: WW Norton; 1990. (An inspiring personal account of how a world-famed cardiothoracic surgeon discovered and dealt with his own PD that began during the height of his career. A very insightful commentary of value to both treating physician and patient alike.)

Shapira AHV. Treatment options in the modern management of Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Neurology. Aug 2007;64(8):1083-1087.