Parasitic infections

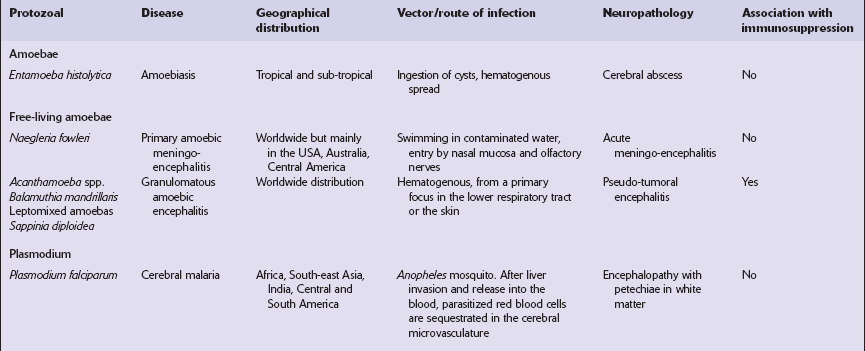

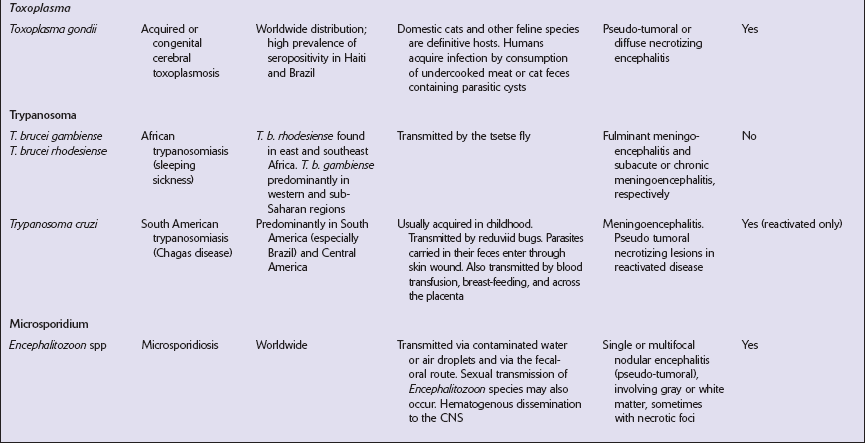

PROTOZOAL INFECTIONS

AMEBIC INFECTIONS

CEREBRAL AMEBIC ABSCESS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

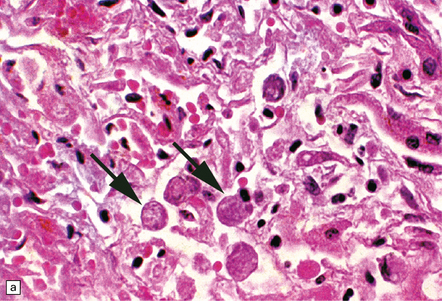

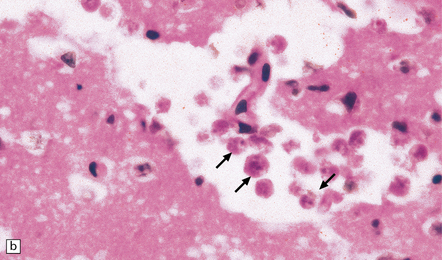

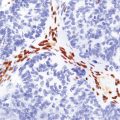

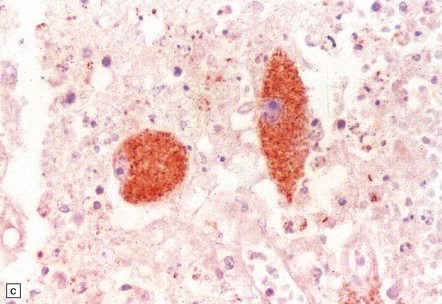

Cerebral amebic abscesses contain inflamed necrotic tissue and it may be difficult to distinguish E. histolytica trophozoites within this tissue from macrophages. The trophozoites are spherical or oval, 15–25 μm in diameter, and have vacuolated cytoplasm and a single nucleus. Occasionally pseudopodia can be seen. In routinely stained sections, the nuclei are round and have a small central karyosome and peripheral chromatin (Fig. 18.1). The cytoplasm contains abundant glycogen.

PRIMARY AMEBIC MENINGOENCEPHALITIS

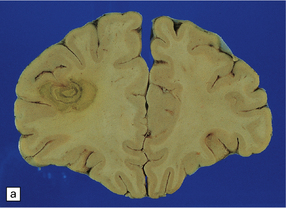

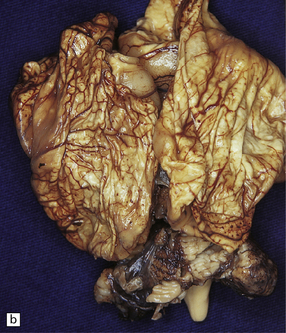

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

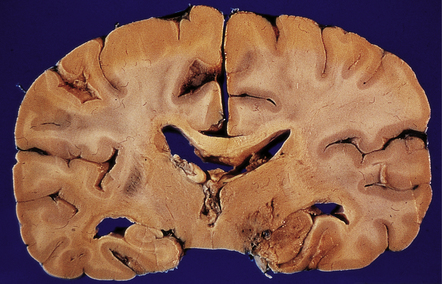

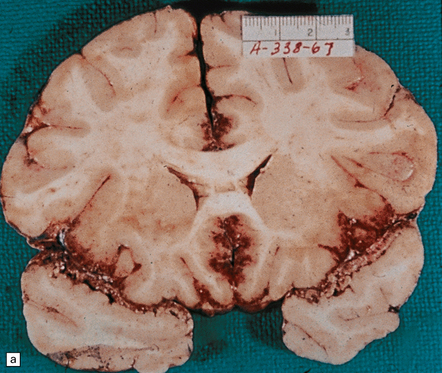

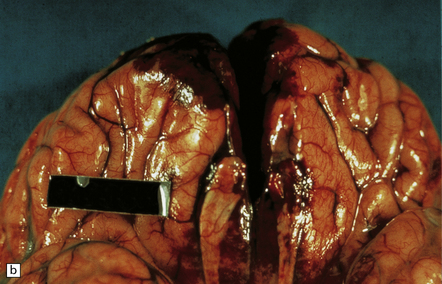

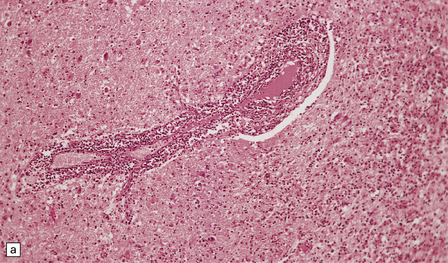

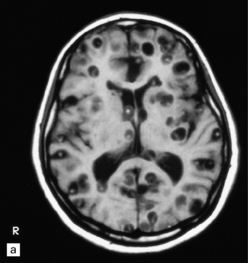

The brain is swollen and there is a hemorrhagic exudate in the meninges over the cerebrum, brain stem, and cerebellum. The olfactory bulbs and tracts and the adjacent parts of the frontal and temporal lobes contain areas of hemorrhagic necrosis (Fig. 18.2).

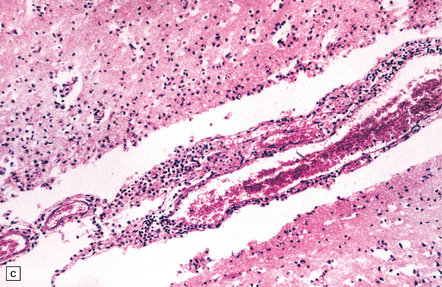

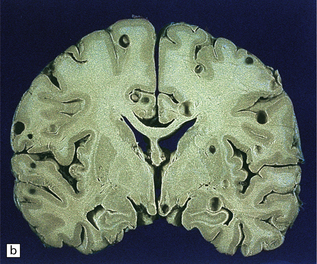

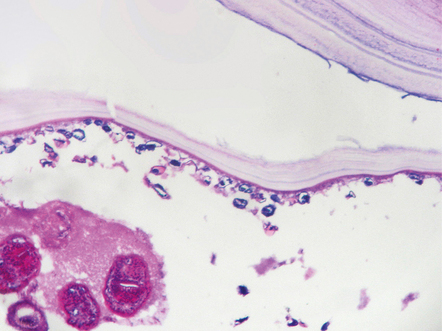

18.2 Primary amebic meningoencephalitis. (a) A hemorrhagic exudate is present in the meninges. There is also hemorrhagic necrosis of the underlying temporal, inferior frontal, and cingulate cortex. (Courtesy of Dr A J Martinez, University of Pittsburgh, USA.) (b) Hemorrhagic necrosis of the frontal poles, olfactory bulbs and tracts, and the underlying inferior frontal cortex. (Courtesy of Dr A J Martinez, University of Pittsburgh, USA.) (c) Scanty inflammatory infiltrates are present in the meninges.

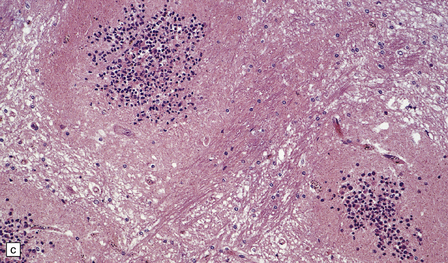

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

A scanty mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 18.2) with focal hemorrhage is seen in the meninges, and there is usually extensive necrosis of brain parenchyma. N. fowleri amebae are present in the subarachnoid space and around vessels in the necrotic parenchyma (Fig. 18.3). Their diameter, of 8–15 μm, is slightly less than that of E. histolytica. They resemble macrophages, but can be distinguished from them by their vesicular nucleus with its large central nucleolus.

GRANULOMATOUS AMEBIC ENCEPHALITIS

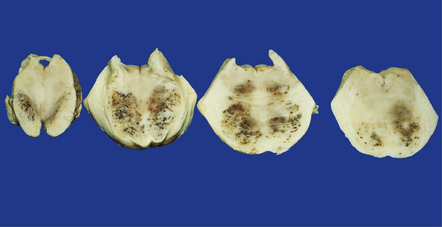

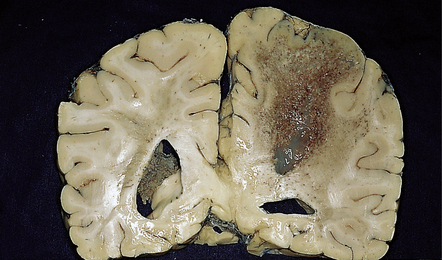

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

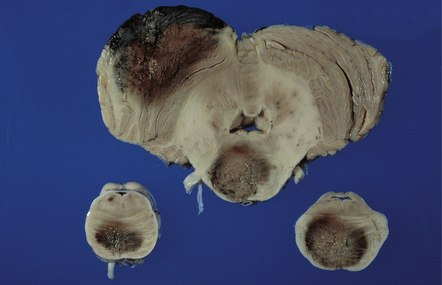

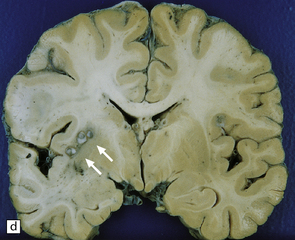

The brain is usually swollen, covered by a diffuse leptomeningeal exudate, and includes foci of softening, hemorrhage, and necrosis, particularly in the anterior part of the cerebral hemispheres, the thalamus (Fig. 18.4), brain stem, and cerebellum (Fig. 18.5).

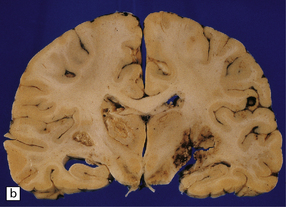

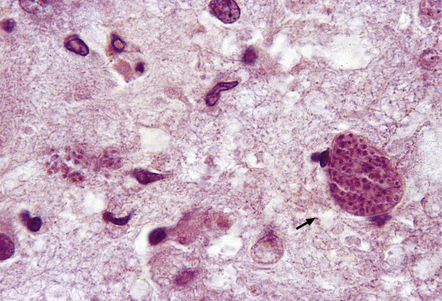

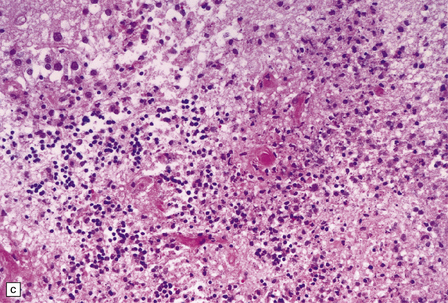

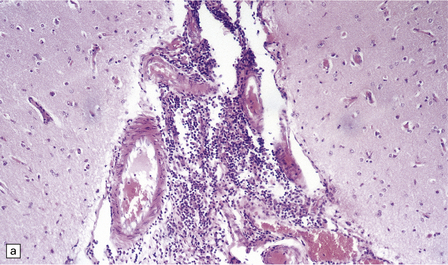

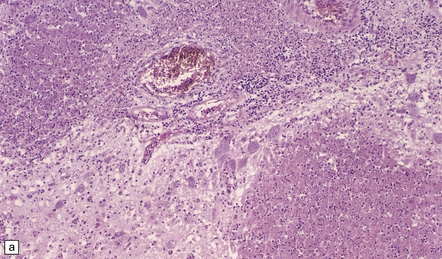

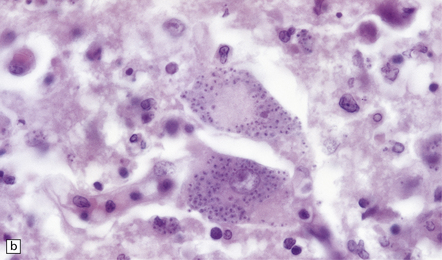

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

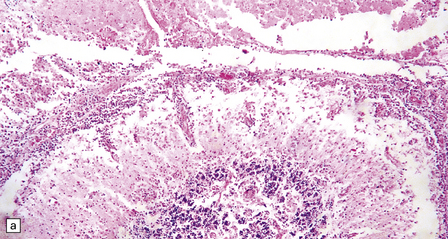

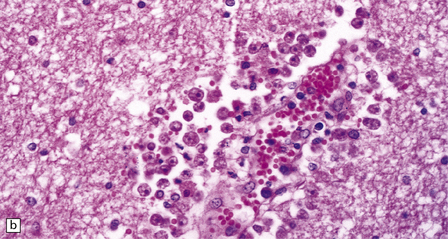

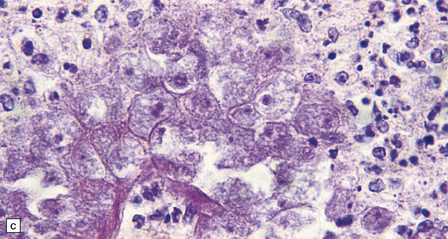

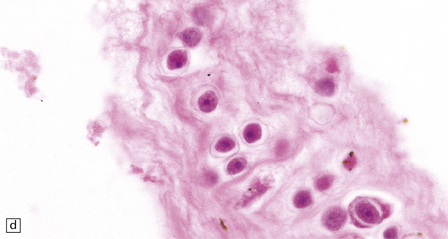

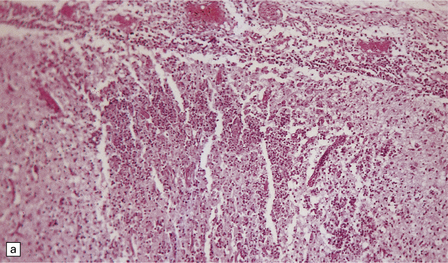

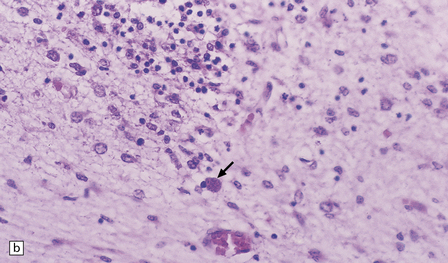

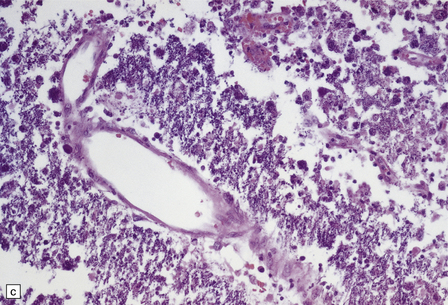

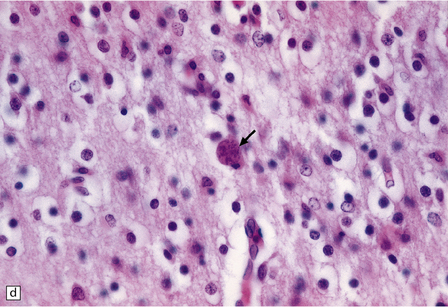

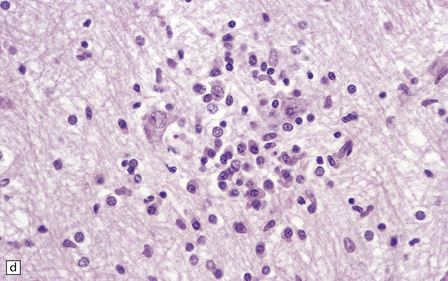

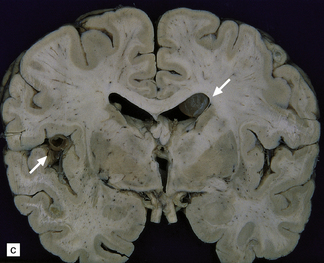

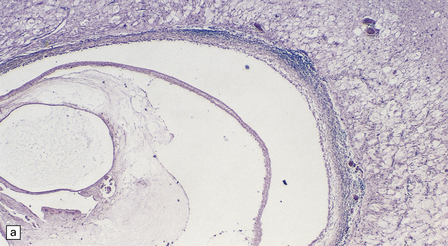

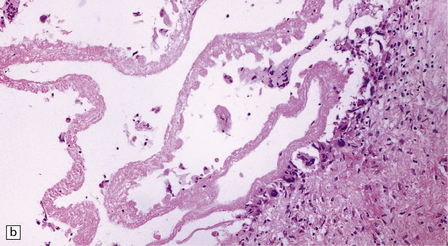

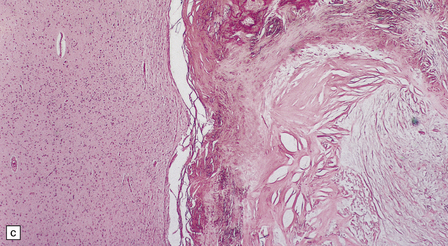

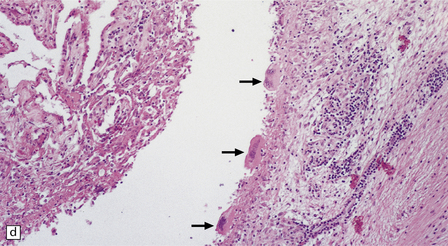

The brain shows foci of chronic inflammation centered around arteries and veins. The inflammation is typically granulomatous and includes lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells, but may be necrotizing. There is also a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the meninges (Fig. 18.6). Acanthamoeba or Balamuthia trophozoites and cysts may be found in and around the walls of affected blood vessels (Fig. 18.6), and also in areas relatively free of inflammation (Fig. 18.6). The amebae are 15–40 μm in diameter and have a prominent vesicular nucleus with a dense central nucleolus. The cysts are surrounded by a double membrane (Fig. 18.6).

18.6 Granulomatous amebic encephalitis. (a) Meningeal and perivascular inflammation with necrosis of adjacent cerebellar tissue. (b) Perivascular Acanthameba trophozoites and scanty mononuclear inflammatory cells in the cerebral white matter. The amebae have a prominent vesicular nucleus with a dense central nucleolus. (c) This section shows perivascular Balamuthia trophozoites and cysts with surrounding inflammation and necrosis. (d) Encysted amebae in the wall of a leptomeningeal blood vessel.

CEREBRAL MALARIA

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

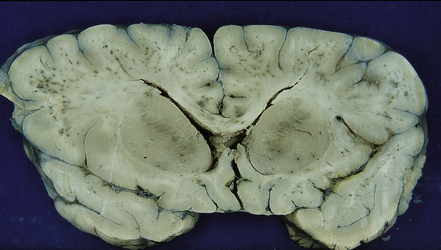

The brain is usually swollen with congested leptomeninges. The cerebral cortex may appear dusky pink color due to marked congestion, or slate gray due to the presence of abundant malarial pigment (Fig. 18.8). The white matter often contains petechial hemorrhages.

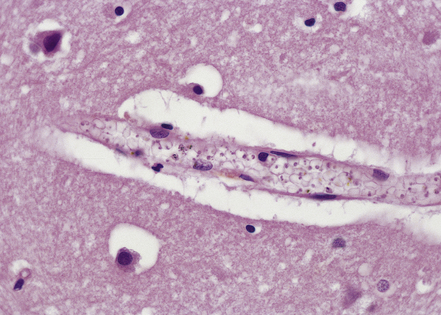

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

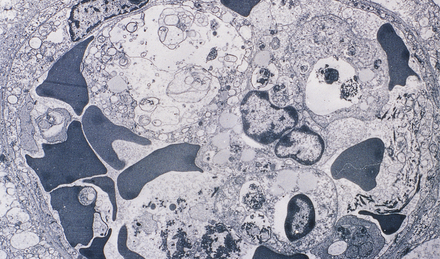

The small vessels are engorged by red blood cells, which may have a ghost-like appearance with poor staining of hemoglobin (Fig. 18.9). Many of these cells, particularly in the gray matter, contain malaria parasites and/or granules of dark malarial pigment, which is related to hematin. Marginated aggregates of red blood cells may appear to be adherent to the vascular endothelium (Fig. 18.10).

18.10 Endothelial adherence of parasitized red blood cells.

Electron micrograph showing a capillary occluded by macrophages with osmiophilic granular pigment and red blood cells containing P. falciparum schizonts. Note that the parasitized red blood cells have knob-like protrusions that are attached to the endothelium. (Courtesy of Dr Carmen L P Lancellotti, Department of Pathology, Santa Casa de Sao Paulo, Brazil.)

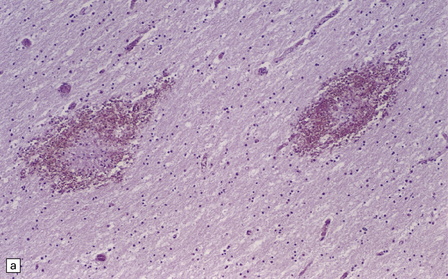

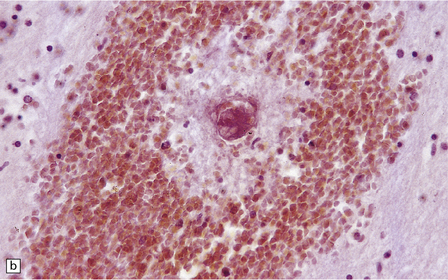

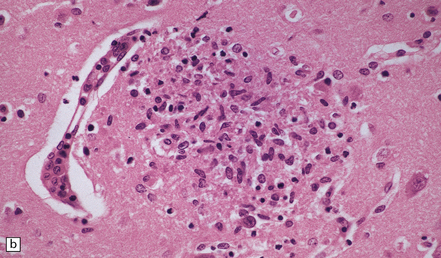

Edema, capillary necrosis, and perivascular hemorrhages are usually evident, and there may be parenchymal and meningeal infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages. Petechial or larger hemorrhages can occur in any part of the brain, but are most common in the white matter and may surround necrotic arterioles and veins (Fig. 18.11). Patients with longer survival may harbor foci of softening and gliosis. Collections of microglia and astrocytes, the so-called Dürck granulomas, are probably related to resorption of ring hemorrhages (Fig. 18.11). The microglia contain iron pigment and lipid.

CEREBRAL TOXOPLASMOSIS

POSTNATALLY-ACQUIRED CEREBRAL TOXOPLASMOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The brain typically contains multifocal necrotic lesions of variable size (Fig. 18.12). There may be associated hemorrhage. Older lesions are cystic due to resorption of necrotic material. The basal ganglia are often involved, but any part of the brain may be affected. Occasionally brain involvement results in an encephalitic process without obvious focal lesions on macroscopic examination.

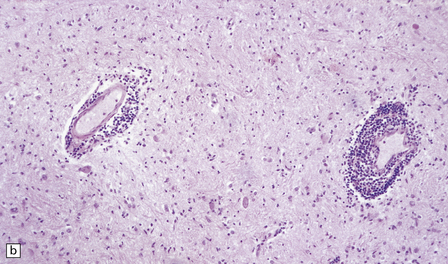

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

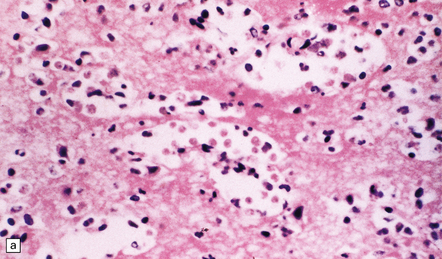

Necrotizing abscesses or foci of coagulative necrosis are surrounded by mononuclear and polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells, newly formed capillaries, reactive astrocytes, and microglia (Fig. 18.13). Infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages surround the blood vessels. Scanty fibrous encapsulation may be evident. Other findings include intimal proliferation and thrombosis, fibrinoid necrosis (Fig. 18.13), and perivascular hemorrhage. The pathological findings depend partly on the degree of impairment of immune function: inflammation is less prominent and fibrosis usually absent in patients whose immune function is severely compromised.

18.13 Histologic features of toxoplasmosis. (a) Inflammation adjacent to a Toxoplasma abscess. A dense perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of inflammatory cells, predominantly lymphocytes and macrophages, is present in the adjacent brain tissue. (b) Toxoplasmosis involving the cerebellar cortex. Note the proliferation of microglia and the presence of extracellular Toxoplasma tachyzoites (arrows). (c) Fibrinoid necrosis of blood vessels in the cerebellum.

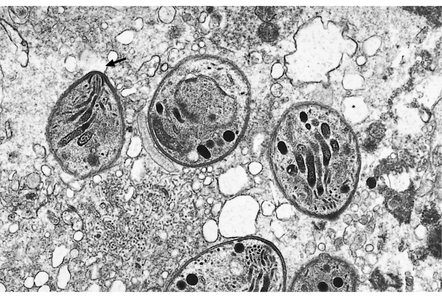

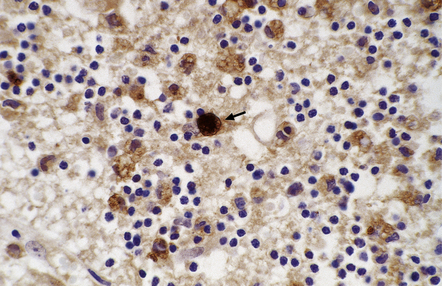

Intracellular and extracellular Toxoplasma tachyzoites (also known as endozoites or trophozoites) are usually abundant. They are oval- or crescent-shaped and measure 2–4 μm by 4–8 μm (Fig. 18.14). Those within cells may be clustered together (in vacuoles or larger pseudocysts) or may appear to lie free in the cell cytoplasm. They can be seen reasonably well when stained with hematoxylin and eosin, but are more readily identified and distinguished from other protozoa immunohistochemically (Fig. 18.15). Cysts measuring 20–100 μm in diameter and containing large numbers of bradyzoites (also known as cystozoites) may occur within, or at the periphery of, the necrotic areas (Figs 18.15, 18.16).

18.14 Ultrastructural appearance of Toxoplasma tachyzoites.

This electron micrograph shows several Toxoplasma tachyzoites, each surrounded by a double-layered pellicle. The conoid of one of the tachyzoites is clearly visible (arrow).

18.15 Immunohistochemical demonstration of Toxoplasma. Immunostained Toxoplasma protozoa are visible within a cyst (arrow) and in the cytoplasm of macrophages.

CONGENITAL TOXOPLASMOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Macroscopic abnormalities occur in the more severe cases and include:

Multifocal or confluent areas of necrosis, particularly in the periventricular and subpial regions (Fig. 18.17).

Multifocal or confluent areas of necrosis, particularly in the periventricular and subpial regions (Fig. 18.17).

18.17 Congenital toxoplasmosis. (a) Foci of subpial and deep white matter necrosis are seen in this case of congenital toxoplasmosis. Some of the subpial foci are partly calcified. (b) Collapsed cerebral hemispheres of a severely hydrocephalic brain in congenital toxoplasmosis.

Hydrocephalus or even hydranencephaly (Fig. 18.17). The brain may collapse after removal from the cranial cavity, because of extensive parenchymal destruction secondary to vascular thrombosis.

Hydrocephalus or even hydranencephaly (Fig. 18.17). The brain may collapse after removal from the cranial cavity, because of extensive parenchymal destruction secondary to vascular thrombosis.

Foci of calcification scattered throughout the brain (Fig. 18.17) in contrast to the predominantly periventricular calcification of congenital cytomegalovirus encephalitis

Foci of calcification scattered throughout the brain (Fig. 18.17) in contrast to the predominantly periventricular calcification of congenital cytomegalovirus encephalitis

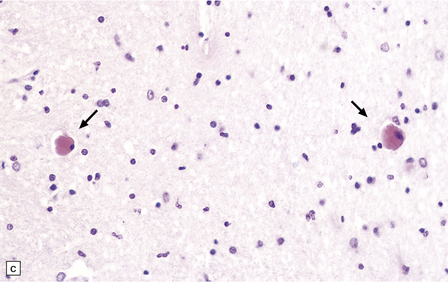

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Active lesions in congenital toxoplasmosis show extensive coagulative necrosis. They are usually associated with lipid-laden macrophages, lymphocytes, and a few neutrophils, which are also present in the leptomeninges (Fig. 18.18). The adjacent brain tissue may contain microglial nodules. Toxoplasma tachyzoites and cysts can be seen in the meningeal exudate, around (rather than within) the necrotic lesions, and are particularly numerous near the ventricular cavities (Fig. 18.18).

18.18 Congenital toxoplasmosis. (a) Focal cortical necrosis with inflammation of the adjacent brain tissue and overlying leptomeninges. (b) A cyst (arrow) and some lymphocytes are present at the periphery of a necrotic lesion. (c) The foci of necrosis tend eventually to undergo mineralization, as illustrated here. (d) Residual Toxoplasma cyst (arrow).

The foci of necrosis eventually tend to undergo mineralization (Fig. 18.18, see also Fig. 18.17). Residual Toxoplasma cysts can usually be found (Fig. 18.18). Ependymal granulations and gliosis may lead to aqueduct stenosis and obstructive hydrocephalus.

TRYPANOSOMIASIS

AFRICAN TRYPANOSOMIASIS (SLEEPING SICKNESS)

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The leptomeninges may be cloudy and the brain swollen and congested. Sometimes the brain is macroscopically normal. Patients who have been treated with melarsoprol may develop acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy (Fig. 18.19) (see Chapter 20).

18.19 Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy may complicate melarsoprol treatment. Petechial hemorrhages and surrounding gray discoloration in the brain stem of a patient with acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy. This was due to melarsoprol treatment of trypanosomiasis. (Courtesy of Professor J H Adams, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow.)

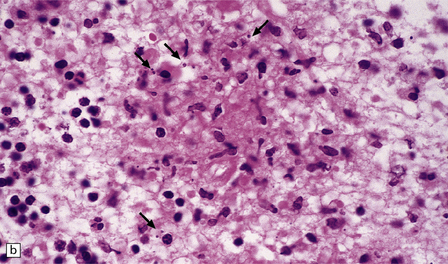

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells surround the cerebral blood vessels and infiltrate the subarachnoid space (Fig. 18.20). Some of the plasma cells contain multiple intracytoplasmic globules of immunoglobulin. These ‘morular cells’ (Fig. 18.20) are characteris tic, but not specific. Other features include a reactive gliosis, and clusters of mononuclear inflammatory cells (Fig. 18.20). Typical microglial nodules may be abundant, especially in T. b. rhodesiense encephalitis, and are often associated with lymphophagocytosis. Trypanosomes are rarely demonstrable in the histologic sections.

18.20 African trypanosomiasis. (a) Meningeal and (b) perivascular parenchymal infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells in trypanosomiasis. Note the diffuse reactive gliosis. (c) Scattered morular cells (arrows) are characteristic. (d) Parenchymal aggregate of mononuclear inflammatory cells. (Courtesy of Professor J H Adams, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow.)

AMERICAN TRYPANOSOMIASIS (CHAGAS’ DISEASE)

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

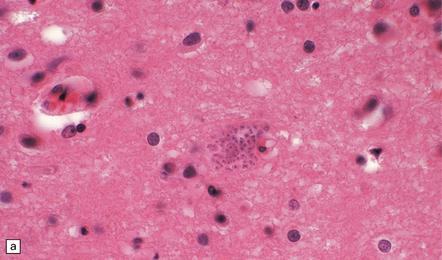

Acute phase: The brain appears swollen and congested, with scattered petechial hemorrhages. Amastigote (Leishmania-like) forms of the parasites are present within glial cells (Fig. 18.21) or less frequently at the center of microglial nodules, which are scattered within the brain parenchyma (Fig. 18.21).

Reactivated disease takes the form of granulomatous or multifocal necrotizing encephalitis (Figs 18.22, 18.23) with abundant amastigote parasites (Fig. 18.23). The identity of the parasite can be confirmed immunohistochemically.

18.22 Necrotizing T. cruzi infection. Large necrotic lesion in the brain of a patient with AIDS and T. cruzi encephalitis.

18.23 T. cruzi multifocal necrotizing encephalitis in AIDS. (a) This pattern of infection with necrosis is restricted to immunocompromised patients. (b) Abundant amastigote parasites, most of which appear to be in astrocytes and macrophages. (c) Immunohistochemical confirmation of the identity of T. cruzi parasites.

MICROSPORIDIOSIS

Microsporidia are single-celled, obligate intracellular parasites.

Microsporidia are single-celled, obligate intracellular parasites.

More than 20 genera of microsporidium are pathogenic in mammals, but Encephalitozoon spp. affect immunosuppressed populations more commonly than other species.

More than 20 genera of microsporidium are pathogenic in mammals, but Encephalitozoon spp. affect immunosuppressed populations more commonly than other species.

In humans, microsporidium can be transmitted via contaminated water or air droplets and via the fecal–oral route. Sexual transmission of Encephalitozoon spp. may also occur.

In humans, microsporidium can be transmitted via contaminated water or air droplets and via the fecal–oral route. Sexual transmission of Encephalitozoon spp. may also occur.

The parasites have an internal coiled tube through which sporoplasm is extruded to pierce and inject infectious sporoplasm into the cytoplasm of the host cell.

The parasites have an internal coiled tube through which sporoplasm is extruded to pierce and inject infectious sporoplasm into the cytoplasm of the host cell.

Disseminated infection with CNS involvement has been reported following kidney, pancreas, and bone marrow transplantation.

Disseminated infection with CNS involvement has been reported following kidney, pancreas, and bone marrow transplantation.

CNS involvement has, very rarely, been reported in immunocompetent hosts.

CNS involvement has, very rarely, been reported in immunocompetent hosts.

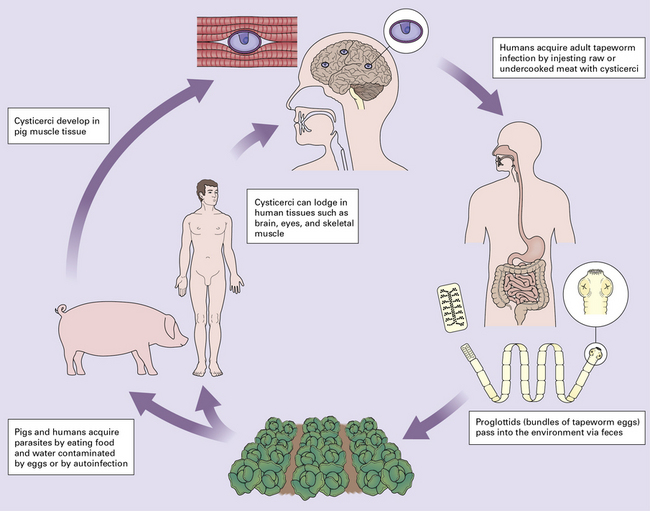

HELMINTHIC INFECTIONS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

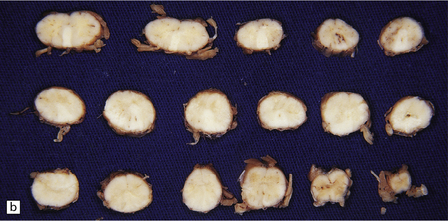

The number of cysts within the CNS varies from one to several hundred (Fig. 18.25). They occur in the parenchyma (especially the gray matter), meninges, or ventricles (Fig. 18.25). The viable intraparenchymal cysticerci are usually 1–2 cm in diameter and contain a single invaginated scolex. After degeneration they become fibrotic and represented by a firm white nodule (Fig. 18.25), which eventually calcifies. The spinal cord is rarely involved.

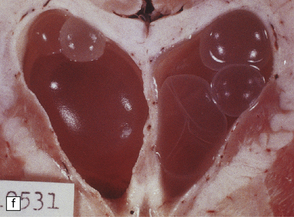

18.25 Cysticercosis. (a) Axial magnetic resonance image of the brain of a patient with cysticercosis. There are multiple visible cysticerci (low signal intensity lesions) and degenerating parasites (producing cysts with higher signal intensity). The small foci of high signal intensity in several of the cysts are caused by the scolex. (Courtesy of Dr B O Colli, Division of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Brazil.) (b) This coronal brain slice contains multiple cysts in the cortex and white matter, some of them with a scolex. (Courtesy of Dr J E H Pittella, Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.) (c) Intraventricular and leptomeningeal cysticerci (arrows). (d) Degenerate cysticerci in the brain parenchyma. After degeneration, the cysticerci become firm white or gray nodules (arrows) that are partly calcified. (e) Cysticerci in the leptomeninges anterior to the optic chiasm. (f) Racemose cysticerci. The cysticerci are forming grape-like clusters in the lateral ventricles. (Courtesy of Dr J E H Pittella, Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.)

The meningeal cysts are small and colorless. They adhere to the pia or float freely in the subarachnoid space (Fig. 18.25), particularly in the sylvian fissure. With time, basal cysts tend to shrink, and the meninges become thickened and fibrotic.

Racemose cysticerci are large multiloculated grape-like clusters of cysts that lack an invaginated scolex. They are usually found in the basilar cisterns or within the ventricular system (Fig. 18.25), especially the fourth ventricle.

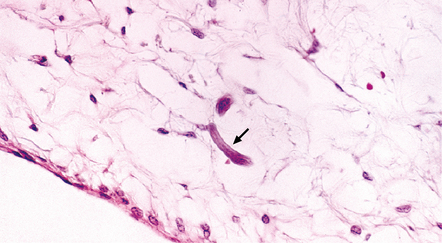

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

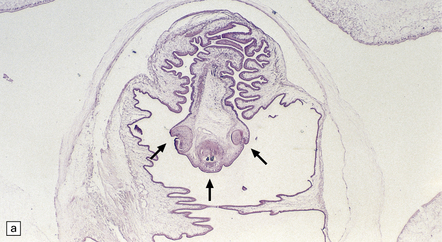

Each scolex has a rostellum with four suckers and a double row of 22–32 hooklets (Fig. 18.26). The cyst wall is sparsely cellular and consists of three histologically distinct layers (Fig. 18.26):

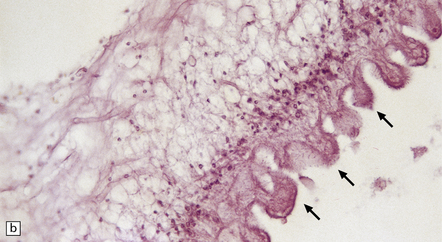

18.26 T. solium. (a) Scolex. The rostellum, with suckers (arrows), is clearly visible. (b) Section through T. solium cyst wall. This consists of a cuticular layer with hair-like protrusions (microtrichia) (arrows), a middle cellular layer, and an inner reticular layer.

An outer or cuticular layer, which is about 3 μm thick, is eosinophilic, and has hair-like protrusions called microtrichia.

An outer or cuticular layer, which is about 3 μm thick, is eosinophilic, and has hair-like protrusions called microtrichia.

An inner reticular or fibrillary layer, which may contain fine mineral concretions.

An inner reticular or fibrillary layer, which may contain fine mineral concretions.

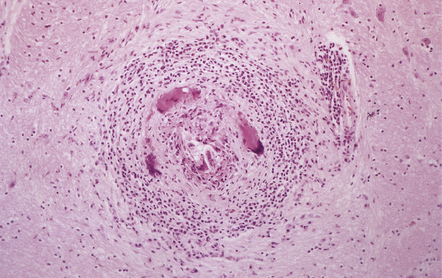

While encysted larvae are viable, the surrounding parenchyma shows minimal reaction. Shortly after the cysticerci die, they are surrounded by neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, foreign body giant cells, and eosinophils (Fig. 18.27), and then enclosed by a zone of granulation tissue, which eventually produces a dense collagenous capsule (Fig. 18.27). The lesion may include necrotic tissue and cholesterol clefts. Old nodules may be entirely fibrotic. Eventually some of the cysts become mineralized (Fig. 18.27).

18.27 Dead cysticercus. (a) An intense inflammatory reaction is present around the dead parasite. (b) The necrotic cyst wall is abutted by a row of foreign body giant cells. There are scattered lymphocytes and microglia in the surrounding brain tissue. (c) In this case, the dead parasite is enclosed in a dense, focally calcified, collagenous capsule. (d) Degeneration of ventricular cysticerci has provoked florid granulomatous inflammation in the choroid plexus and periventricular tissue. Multinucleated giant cells (arrows) are present in the wall of the ventricle.

Ventricular cysticerci usually cause a granular ependymitis. Degeneration of racemose cysticerci in the ventricles or subarachnoid space may provoke a florid granulomatous inflammatory reaction (Fig. 18.27).

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The wall of the cyst (Fig. 18.28) consists of:

18.28 Hydatid (echinococcal) cyst. Section through the edge of a cyst, showing part of the cyst wall and an adjacent brood capsule within which are several protoscolices. The irregularly shaped dark blue fragments of calcified material just beneath the cyst wall are known as calcaneus corpuscles.

An outer layer of fibrous tissue, derived from the host.

An outer layer of fibrous tissue, derived from the host.

An intermediate laminated, chitinous or cuticular layer.

An intermediate laminated, chitinous or cuticular layer.

A thin inner germinal layer to which oval brood capsules are usually attached.

A thin inner germinal layer to which oval brood capsules are usually attached.

The interior of the cyst contains numerous small protoscolices in brood capsules (Fig. 18.28). Apart from mild gliosis and occasional lymphocytic cuffing of blood vessels in the immediate vicinity, there is little other reaction to the cysts.

NEMATODES

STRONGYLOIDIASIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

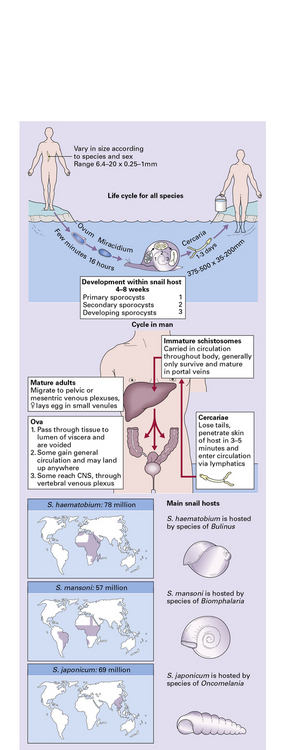

TREMATODES

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Miliary granulomas may be seen scattered throughout the brain, but are most numerous in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex and the deep gray matter. Sometimes the lesions are solitary and mimic a tumor. Spinal schistosomiasis can cause marked swelling of the affected cord segments (Fig. 18.32). Granulomas may be studded over the surface of the brain or cord, or agglomerated to form nodules, which protrude from the surface and occasionally invade the dura

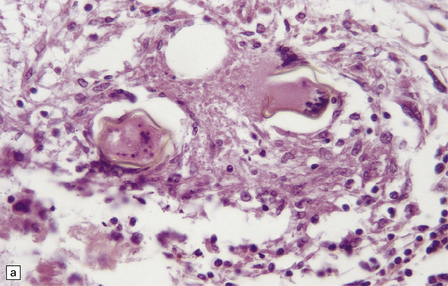

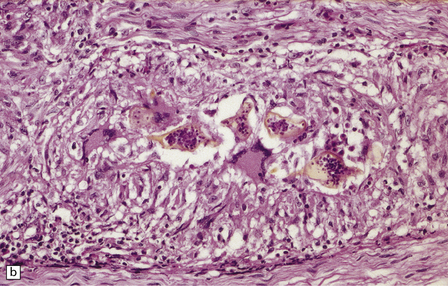

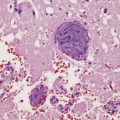

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The histologic reaction to the ova varies from nothing to florid granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells, marked fibrosis, and adjacent gliosis (Fig. 18.33). Eosinophils are usually present. Some patients develop focal arteritis.

REFERENCES

Chacko, G. Parasitic diseases of the central nervous system. Semin Diagn Pathol.. 2010;27:167–185.

Feasey, N., Wansbrough-Jones, M., Mabey, D.C., et al. Neglected tropical diseases. Br Med Bull.. 2010;93:179–200.

Jansen, M., Corcoran, D., Bermingham, N., et al. The role of biopsy in the diagnosis of infections of the central nervous system. Ir Med J.. 2010;103:6–8.

Katchanov, J., Nawa, Y. Helminthic invasion of the central nervous system: many roads lead to Rome. Parasitol Int.. 2010;59:491–496.

Kristensson, K., Mhlanga, J.D., Bentivoglio, M. Parasites and the brain: neuroinvasion, immunopathogenesis and neuronal dysfunctions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol.. 2002;265:227–257.

Lawn, S.D. Immune reconstitution disease associated with parasitic infections following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Curr Opin Infect Dis.. 2007;20:482–488.

Lucas, S., Bell, J., Chimelli, L., Parasitic and fungal infections. 8th ed. Greenfields’ neuropathology vol. 1. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008. [1447–1512].

Lv, S., Zhang, Y., Steinmann, P., et al. Helminth infections of the central nervous system occurring in Southeast Asia and the Far East. Adv Parasitol.. 2010;72:351–408.

Deol, I., Robledo, L., Meza, A., et al. Encephalitis due to a free-living amoeba (Balamuthia mandrillaris): case report with literature review. Surg Neurol.. 2000;53:611–616.

Khan, N.A. Acanthamoeba and the blood-brain barrier: the breakthrough. J Med Microbiol.. 2008;57:1051–1057.

Marciano-Cabral, F., Cabral, G. Acanthamoeba spp as agents of disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev.. 2003;16:273–307.

Martinez, A.J., Visvesvara, G.S. Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:583–598.

Idro, R., Jenkins, N.E., Newton, C.R. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neurol.. 2005;4:827–840.

Idro, R., Marsh, K., John, C.C., et al. Cerebral malaria: mechanisms of brain injury and strategies for improved neurocognitive outcome. Pediatr Res.. 2010;68:267–274.

Lou, J., Lucas, R., Grau, G.E. Pathogenesis of cerebral malaria: recent experimental data and possible applications for humans. Clin Microbiol Rev.. 2001;14:810–820.

Hill, D., Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.. 2002;8:634–640.

Martin, S. Congenital toxoplasmosis. Neonatal Netw.. 2001;20:23–30.

Montoya, J.G., Kovacs, J.A., Remington, J.S. Toxoplasma gondii. In: Mandell G.L., Bennet J.E., Dolin R., eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:3170–3198.

Almeida, E.A., Lima, J.N., Lages-Silva, E., et al. Chagas’ disease and HIV co-infection in patients without effective antiretroviral therapy: prevalence, clinical presentation and natural history. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.. 2010;104:447–452.

Corti, M. AIDS and Chagas’ disease. AIDS Patient Care Stds.. 2000;14:581–588.

Enanga, B., Burchmore, R.J., Stewart, M.L., et al. Sleeping sickness and the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci.. 2002;59:845–858.

Kirchhoff, L.V. Agents of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). In: Mandell G.L., Bennet J.E., Dolin R., eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:3165–3170.

Kirchhoff, L.V. Trypanosoma species (American trypanosomiasis, Chagas’ disease): Biology of trypanosomes. In: Mandell G.L., Bennet J.E., Dolin R., eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:3157–3164.

Pittella, J.E. Central nervous system involvement in Chagas disease: a hundred-year-old history. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.. 2009;103:973–978.

Rodgers, J. Trypanosomiasis and the brain. Parasitology.. 2010;137:1995–2006.

Silva, N., O’Bryan, L., Medeiros, E., et al. Trypanosoma cruzi meningoencephalitis in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol.. 1999;20:342–349.

Weiss, L.M. Microsporidiosis. In: Mandell G.L., Bennet J.E., Dolin R., eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:3237–3254.

Fleury, A., Escobar, A., Fragoso, G., et al. Clinical heterogeneity of human neurocysticercosis results from complex interactions among parasite, host and environmental factors. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.. 2010;104:243–250.

Kraft, R. Cysticercosis: an emerging parasitic disease. Am Fam Physician.. 2007;76:91–96.

Nourbakhsh, A., Vannemreddy, P., Minagar, A., et al. Hydatid disease of the central nervous system: a review of literature with an emphasis on Latin American countries. Neurol Res.. 2010;32:245–251.

Pamir, M.N., Ozduman, K., Elmaci, I. Spinal hydatid disease. Spinal Cord.. 2002;40:153–160.

Pittella, J.E. Neurocysticercosis. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:681–693.

Rengarajan, S., Nanjegowda, N., Bhat, D., et al. Cerebral sparganosis: a diagnostic challenge. Br J Neurosurg.. 2008;22:784–786.

Sinha, S., Sharma, B.S. Neurocysticercosis: a review of current status and management. J Clin Neurosci.. 2009;16:867–876.

Taratuto, A.L., Venturiello, S.M. Echinococcosis. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:673–679.

Alto, W. Human infections with Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Pac Health Dialog.. 2001;8:176–182.

Clausen, M.R., Meyer, C.N., Krantz, T., et al. Trichinella infection and clinical disease. QJM.. 1996;89:631–636.

Pawlowski, Z. Toxocariasis in humans: clinical expression and treatment dilemma. J Helminthol.. 2001;75:299–305.

Pien, F.D., Pien, B.C. Angiostrongylus cantonensis eosinophilic meningitis. Int J Infect Dis.. 1999;3:161–163.

Taratuto, A.L., Venturiello, S.M. Trichinosis. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:663–672.

Tsai, H.C., Liu, Y.C., Kunin, C.M., et al. Eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis: report of 17 cases. Am J Med.. 2001;111:109–114.

Carod-Artal, F.J. Neurological complications of Schistosoma infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.. 2008;102:107–116.

Ferrari, T.C., Moreira, P.R., Cunha, A.S. Spinal-cord involvement in the hepato-splenic form of Schistosoma mansoni infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol.. 2001;95:633–635.

Pittella, J.E. Neuroschistosomiasis. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:649–662.