50 Parasitic and Fungal Disorders and Neurosarcoidosis

Cerebral Malaria

Clinical Vignette

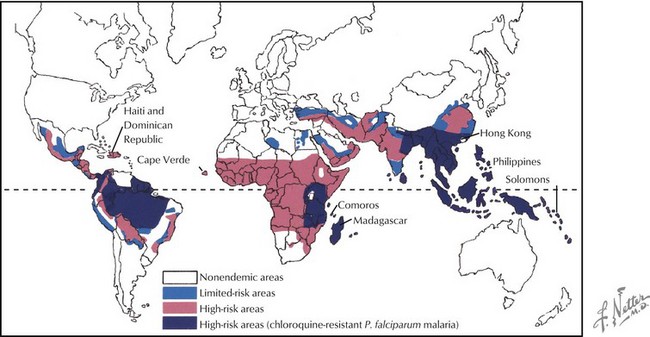

Malaria continues to have a global presence, primarily affecting individuals living in South and Central America, Africa, and Asia (Fig. 50-1). Close to a half billion individuals are affected annually with up to a million deaths each year. Previously endemic in the United States, public health measures have greatly decreased its incidence here. However, at least a thousand cases are reported annually here and are primarily related to P. falciparum affecting travelers to endemic geographic areas.

Therapy

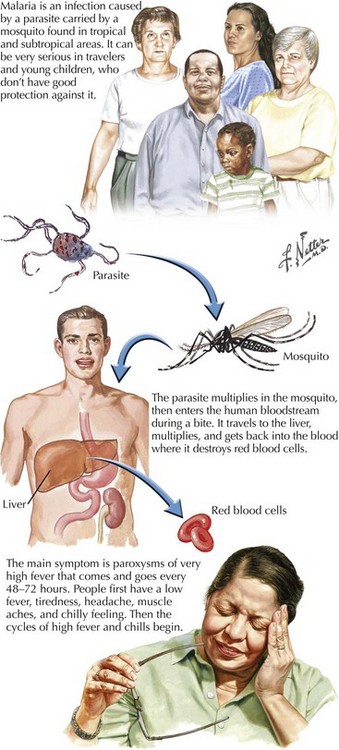

Increased drug resistance has led to combination therapy for malaria. The treatment of cerebral malaria consists of either intravenous quinidine or artesunate accompanied by doxycycline (Fig. 50-2). Intravenous quinidine has to be administered in an ICU setting with electrocardiographic monitoring, as it may lead to severe arrhythmias. Exchange transfusion should be strongly considered for persons with a parasite density of more than 5–10% or even with a lower level of parasitemia if the cerebral malaria is severe or other complications of the malaria occur, including non–volume overload pulmonary edema, or renal complications.

African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness)

Clinical Features

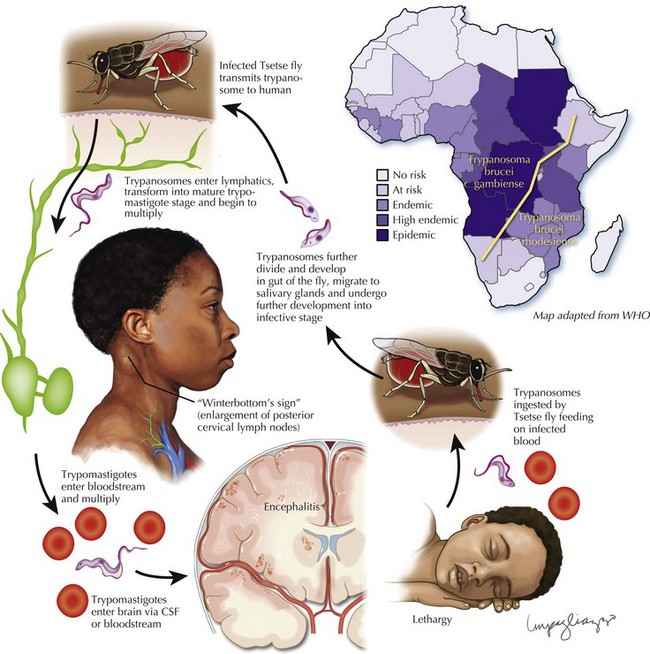

Once the neurologic manifestations emerge, the patient often has developed an advanced stage of central nervous system (CNS) infection. Personality changes are common; patients are frequently mistaken as having psychiatric disorders, as in this case. In the early phases of CNS disease, a disruption of the normal circadian sleep rhythm occurs (Fig. 50-3).

Cysticercosis

Epidemiology

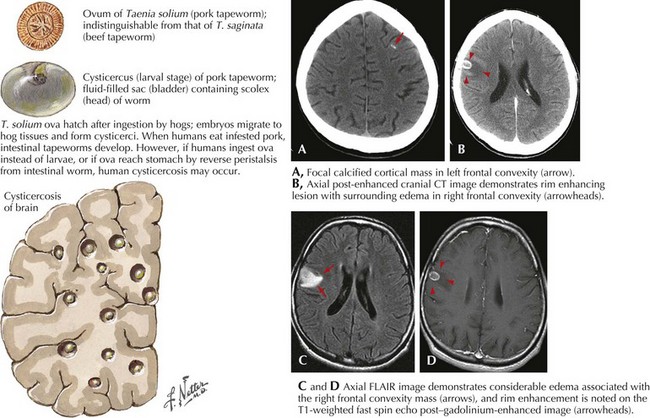

Cysticercosis is a relatively common cause of seizure disorders, particularly in individuals from Central and South America, including those who have immigrated to the United States. It may occur in both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised individuals. It results from infection with the larval form of the porcine tapeworm Taenia solium. Humans acquire the adult tapeworm by eating undercooked pork and become infected with the larval stage (cysticercus) by ingesting tapeworm eggs. Eggs hatch within the small intestine, burrow into venules, and are carried to distant sites, including the CNS and muscle. Because the larvae are relatively large, they may lodge in the subarachnoid space, ventricles, or brain tissue (Fig. 50-4).

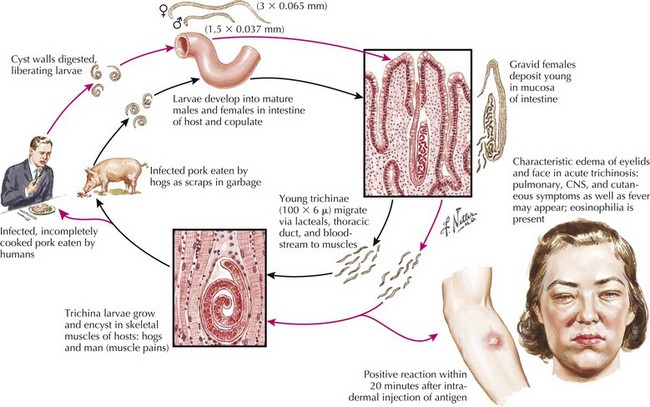

Trichinosis

Shortly after ingestion, one may develop significant upper gastrointestinal distress with nausea and vomiting (Fig. 50-5). Periorbital edema may develop but may be relatively transient, disappearing in few days. If heavily infested pork is ingested, this is soon followed by severe generalized myalgia and sometimes an overwhelming encephalomyelitis and fever not unlike acute bacterial meningitis. Cardiac and diaphragmatic muscle is also at risk and may lead to a fatal outcome when severely infested by the trichinella organism. Very rarely there may be cerebral infestation leading to seizures. Major clinical clues to diagnosis include history of periorbital edema, overwhelming myalgia, and a blood count demonstrating a marked leukocytosis with a very marked degree of eosinophilia (>700 cells/mm3).

Schistosomiasis

Complement fixation or liver/rectal mucosa biopsy provide the best diagnostic methodology.

Clinical Vignette

Diagnosis

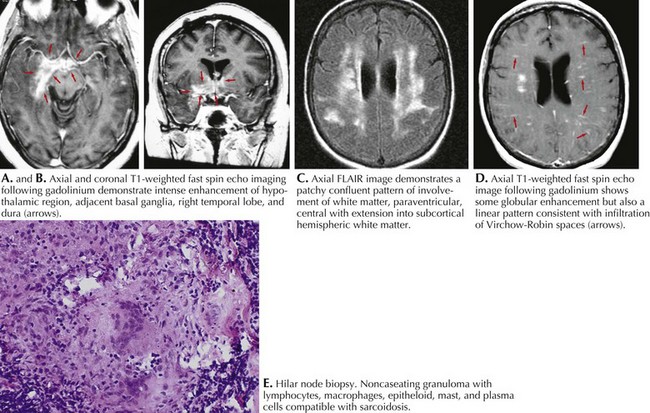

A definitive diagnosis requires a tissue specimen, most typically a hilar node biopsy as illustrated by the above vignette. Often one can gain supportive clues from a cranial MRI, particularly with its high sensitivity especially involving the leptomeninges. However, this has a low specificity, as it may mimic MS in its propensity for some white matter involvement. At other times, MRI may demonstrate lesions mimicking a tumor (Fig. 50-6). The CSF is abnormal in 80% of NS patients, not only a cellular response but also an elevated ACE, something that may only be positive here rather than the serum. Chest radiographs are positive in more than half of the patients. Chest CT is sometimes positive when routine chest radiographs are normal. Lastly an otherwise unexplained hypercalcemia as well as abnormal liver function tests may also give further hint that NS is present.

Overview of Fungal Infections

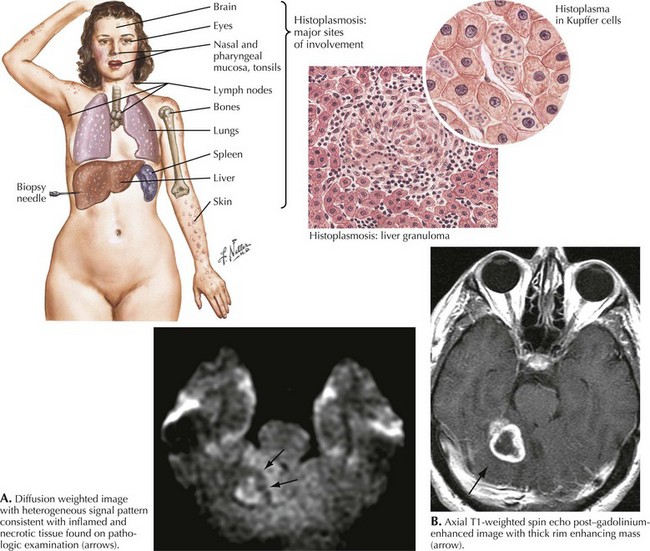

Cryptococcus neoformans and Coccidioides immitis are the most common fungi responsible for central nervous system fungal disease. These two fungi together with Histoplasma capsulatum are capable of causing disease in both healthy individuals and immunocompromised hosts. As cryptococcal disease is discussed in Chapter 51, this section primarily discusses CNS disease caused by H. capsulatum and C. immitis.

Histoplasmosis

Epidemiology

CNS histoplasmosis is a manifestation of disseminated disease and is uncommon in North America. It mimics tuberculosis with parenchymal involvement occurring as single or multiple focal granulomas (Fig. 50-7). Granulomatous basilar meningitis may also occur. Abscess formation is rare except in immunocompromised hosts. Patients usually present with signs and symptoms of subacute meningitis with fever, stiff neck, and photophobia. Focal neurologic deficits are more common in CNS histoplasmosis than either cryptococcosis or coccidioidomycosis.

Coccidioidomycosis

Centers for Disease Control Division of Parasitic Disease—African trypanosomiasis http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/trypanosomiasis/default.htm Accessed February 5, 2009

Coccidioidomycosis http://www.idsociety.org/content.aspx?id=9200#cocc

Fungal Infections http://www.idsociety.org/content.aspx?id=9200

Histoplasmosis http://www.idsociety.org/content.aspx?id=9200#hist

. Practice Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at http://www.idsociety.org/Content.aspx?id=9088 Accessed February 5, 2009. Evidence-based statements developed to assist practitioners and patients in making decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. Guidelines for treatment of infections by organ system and organism may be found here

World Health Organization—African trypanosomiasis http://www.who.int/topics/trypanosomiasis_african/en/ Accessed February 5, 2009