Chapter 63B Palliation of pancreatic and periampullary tumors

Overview

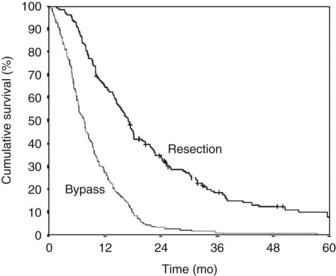

Pancreatic and periampullary tumors are the fifth most common cause of cancer-related death in the Western world (DiMagno et al, 1999; Greenlee et al, 2000). The incidence in the United States is approximately 10 per 100,000 persons per year. Most of these tumors are pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and the survival is poor (DiMagno et al, 1999; Greenlee et al, 2000; Gudjonsson, 1995, 2009; Kuhlmann et al, 2004). Despite surgical treatment with or without radiotherapy and chemotherapy, the overall 5-year survival is approximately 4% and has barely improved over the last few decades (Fig. 63B.1; Gudjonsson, 2009; Kuhlmann et al, 2004). Most patients are seen initially with “incurable” disease, owing to extensive local disease or metastases at the time of diagnosis (Sener et al, 1999). Confusion surrounds the terminology, however, with the words incurable, inoperable, and unresectable having a variety of interpretations. Use of the term unresectable partly depends on the local surgical philosophy (e.g., accepting a resection of the mesenteric artery portal vein and macroscopically nonradical R2 resections). This surgical philosophy is not only a country-related or regional pattern, it also may be influenced by the experience at the center and the local tradition of the surgeons. The strong relationship between outcome and hospital mortality may play a role in the indication for resection and acceptance of palliative resections (Alexakis et al, 2004; Birkmeyer et al, 2003; Gouma et al, 2000).

It has been questioned whether cure is possible at all in patients with pancreatic cancer (Gudjonsson, 1995, 2009). Gudjonsson summarized the literature, and after adjusting for calculations and duplications, suggested that the total number of 5-year survivors is hardly more than 700 to 800.

There is consensus, however, that patients who undergo resection have the best chance for long-term survival (Alexakis et al, 2004). A recent study showed up to 20 years survival after resection (Adham, 2008). Survival data for patients with distal bile duct carcinoma do not differ from data for patients with pancreatic cancer. Patients with ampullary tumors have a 5-year survival of 20% to 45%, and only a few go straight to palliative treatment (de Castro et al, 2004).

Overall, most patients have palliative treatment, and palliation of symptoms is still the major focus. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002), palliative care is aimed at the improvement of the quality of life (QOL) of patients who face a life-threatening illness and at the prevention or relief of pain and symptoms. The three most important symptoms that should be treated in advanced pancreatic and periampullary cancer are 1) obstructive jaundice, 2) duodenal obstruction, and 3) pain.

The decision to aim for palliative treatment can be made at two different points during the disease (Nakakura & Warren, 2007). The first decision generally is made after staging procedures, and a selection is made for potential curative surgery, palliative surgery, or nonsurgical (endoscopic) palliation. Recently, another option, preoperative radiochemotherapy and subsequent exploration, has been introduced for patients with borderline resectable lesions in an attempt to reduce local tumor ingrowths (Abrams et al, 2009; Bjerregaard et al, 2009).

Accurate initial staging is the crucial step for the selection of surgical and nonsurgical (palliative) treatment. Radiologic imaging techniques have evolved rapidly in the last decade. Various methods, such as contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), have enhanced the accuracy of radiologic staging, and noninvasive staging procedures are currently the first choice (Alexakis et al, 2004; McMahon et al, 2001; Phoa et al, 2000). Recent evaluation has identified the “new group” of patients, the borderline resectable patients, for pretreatment assessment, and criteria have been described (Callery et al, 2009). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is no longer used as a diagnostic procedure.

The role of diagnostic laparoscopy in combination with laparoscopic sonography has been studied extensively in the past (Bemelman et al, 1995; Friess et al, 1998; Nieveen van Dijkum et al, 2003; Pisters et al, 2001; Tilleman et al, 2004), but its role has diminished. A review showed that no data justify the routine use of staging laparoscopy (Pisters et al, 2001). In a recent series, however, metastasis or local ingrowth was found in 27%. Some authors therefore suggest that it should be used selectively for patients with larger tumors and tumors located in the body and tail (Chang, 2009).

Depending on local philosophy, patients who are found to have a resectable tumor at preoperative noninvasive diagnostic workup should undergo an exploratory laparotomy immediately without preoperative biliary drainage (van der Gaag et al, 2010). Patients with unresectable or incurable disease found during exploration (11% to 50%) are generally considered to be best treated with surgical palliation (Nieveen van Dijkum et al, 2003; Pisters et al, 2001; Sohn et al, 1999). This chapter evaluates the current knowledge of different aspects of surgical and nonsurgical palliative treatment for the symptoms mentioned above: obstructive jaundice, duodenal obstruction, and pain.

Obstructive Jaundice

At the time of diagnosis, 90% of patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors present with obstructive jaundice. Obstructive jaundice is associated clinically with jaundiced skin and sclerae, nausea, pruritus, dark-colored urine, and decoloring of the stool. More severe consequences are liver dysfunction and eventually hepatic failure secondary to bile stasis and cholangitis, which is found more frequently in patients with ampullary lesions compared with patients with pancreatic cancer. Relief of obstructive jaundice causes a dramatic increase in the QOL of patients and should always be achieved (Abraham et al, 2002; Crippa et al, 2008).

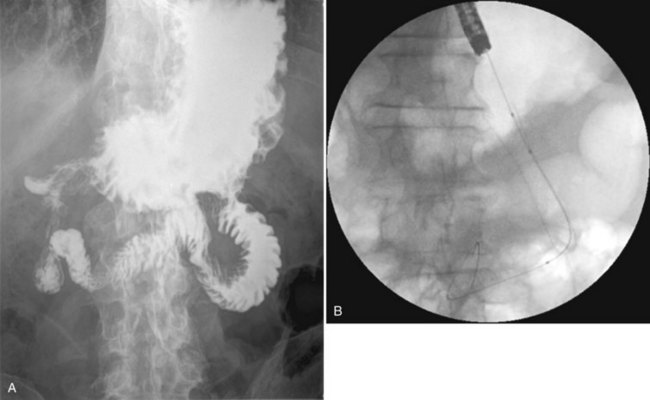

Biliary drainage can be achieved nonsurgically by placement of a biliary stent (endoscopic or percutaneous; see Chapter 18) or surgically by performing a biliary bypass (see Chapter 29). The success rate for short-term relief of biliary obstruction is comparable for surgical and nonsurgical biliary drainage procedures and ranges from 80% to 100%.

In the past, endoscopic biliary drainage was widely performed with plastic stents (polytef [Teflon] and polyethylene). Plastic stents can cause complications such as migration and occlusion, reported in 40%. A new stent type for endoscopic treatment is the self-expandable, covered metallic stent. Compared with plastic stents, expandable stents have a longer patency, but they generally cannot be removed after placement (Davids et al, 1992; Kaassis et al, 2003; Weber et al, 2009).

A surgical bypass can be performed by a hepaticojejunostomy alone or by a double bypass including a gastroenterostomy. In earlier studies, surgical bypass was associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality (Watanapa & Williamson, 1992).

Surgical Palliation of Obstructive Jaundice

Different surgical approaches can be used to obtain adequate biliary drainage. External biliary drainage by a T-tube has been used in the past but results in loss of appetite, and electrolyte and fluid imbalances frequently accompany external drainage. Internal biliary drainage generally is preferred and is performed by a cholecystojejunostomy, choledocho(hepatico)jejunostomy or choledochoduodenostomy (Watanapa & Williamson, 1992). In the past, cholecystojejunostomy was preferred because it is a relatively simple procedure (Rappaport & Villalba, 1990). In an extensive review, the success rate of cholecystojejunostomy to relieve obstructive jaundice was lower, however, compared with choledochojejunostomy (Watanapa & Williamson, 1992). A randomized controlled trial by Sarfeh and colleagues (1988) also showed that the technically more difficult choledochojejunostomy is preferred over a cholecystenterostomy, owing to the lower rate of recurrent jaundice and cholangitis and better patency of the bypass.

A choledochoduodenostomy is not recommended because it is generally believed that this drainage procedure frequently results in recurrent jaundice from local tumor ingrowth into the duodenum and the distal common bile duct, including the entrance of the cystic duct. A few cohort studies show low procedure-related complication rates and low rates of recurrent jaundice after choledochoduodenostomy (Di Fronzo et al, 1999).

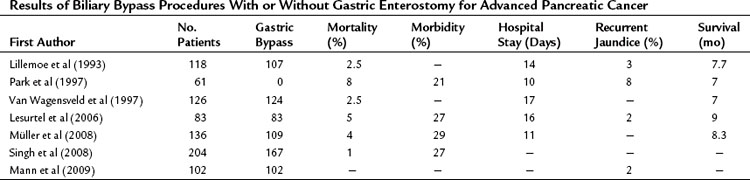

At our institution, a side-to-side Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy is routinely performed after removal of the gallbladder in case of detection of advanced disease or metastases. According to the extension of dissection, in an attempt to prove locally advanced disease by ingrowth at the proximal portal vein, the common bile duct may be transected in an early phase of the procedure, and an end-to-side anastomosis is made by a one-layer running suture. This procedure can be performed with a low mortality rate and acceptable morbidity. The mortality rate in earlier studies, as well as most “outdated” randomized controlled trials from the 1990s (see below), was high and varied between 15% and 24%. However, recent studies showed mortality rates between 1% and 8%, morbidity rates between 21% and 29%, and shorter hospital stay (10 to 17 days) with a relatively low incidence of recurrent jaundice. The mean survival varied between 7 and 9 months (Table 63B.1).

Surgical or Endoscopic or Percutaneous Drainage of Obstructive Jaundice

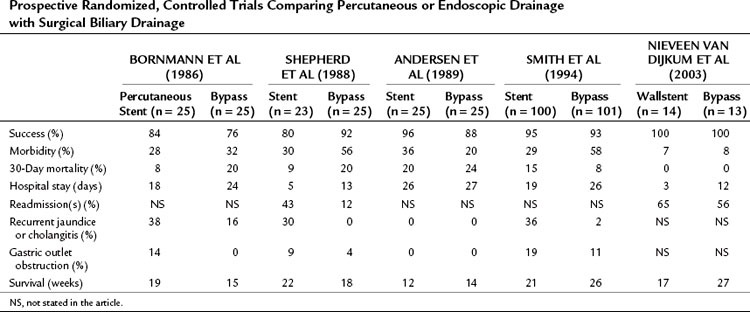

Five prospective, randomized controlled trials have been performed, four of which compared surgical biliary drainage and endoscopic drainage (Andersen et al, 1989; Bornmann et al, 1986; Nieveen van Dijkum et al, 2003; Shepherd et al, 1988; Smith et al, 1994). In the first trial by Bornmann and associates (1986), percutaneous biliary drainage was used, and no differences were found between percutaneous and surgical palliation (Table 63B.2). The other studies were performed between 1988 and 1994, except for the study done by Nieveen van Dijkum and colleagues (2003), in which patients underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy as a final staging procedure, and randomization was performed after pathology had proven metastasis. The small number of patients randomized hampered the studies by Shepherd and associates (1988) and Andersen and colleagues (1989). Shepherd and colleagues predominantly used 7-Fr endoprotheses, which are known to have a higher occlusion rate than 10- or 12-Fr endoprotheses or Wallstents currently used (Davids et al, 1992). A study by Shepherd and colleagues (1988) had a relatively high rate of recurrent jaundice and cholangitis. The length of follow-up in both studies was unclear, and the registration of complications and the readmission rate were limited. In the study by Smith and coworkers (1994), 201 patients were randomized. A higher procedure-related mortality rate was found after bypass compared with stenting (14% vs. 3%), and the 30-day mortality rate was not significantly different (8% vs. 15%) but was still relatively high. Major complications after bypass versus stenting were significantly different (29% vs. 11%), but minor complications were comparable (29% vs. 18%). The recurrence of jaundice and cholangitis during follow-up was significantly higher after stenting (36% vs. 2%), but survival was comparable between groups (Smith et al, 1994).

Table 63B.2 Prospective Randomized, Controlled Trials Comparing Percutaneous or Endoscopic Drainage with Surgical Biliary Drainage

Taylor and associates (2000) conducted a meta-analysis using the three above-mentioned studies of endoscopic stenting and concluded that more treatment sessions were required after stent placement than after surgery, with a common odds ratio (OR) estimated to be 7.23. This ratio indicates a more than sevenfold increased risk of additional treatment sessions after stenting. No significant difference between the two treatment strategies was found concerning 30-day mortality rate.

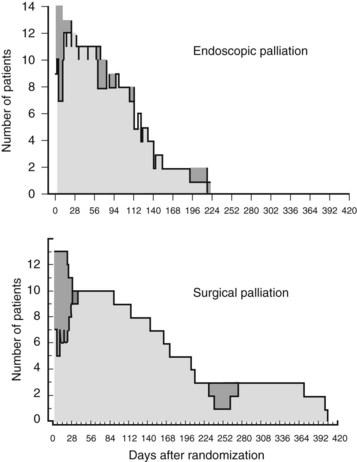

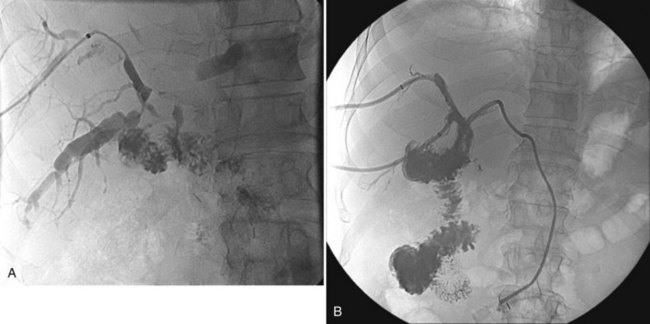

The more recent randomized study by Nieveen van Dijkum and colleagues (2003) analyzed the value of diagnostic laparoscopy for patients with a periampullary carcinoma. Patients who were found to have incurable disease owing to pathology-proven metastases were allocated to either surgical (double bypass) or endoscopic palliation by a Wallstent. No difference was found in procedure-related morbidity or number of readmitted patients between the surgically and endoscopically palliated patients (see Table 63B.2). The survival was 192 days and 116 days in the surgical and endoscopic groups, respectively (P = .05; Fig. 63B.2). This study concerns a select group of patients who were believed to have a resectable tumor after conventional radiologic staging, leading to a low (zero) procedure-related mortality.

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Symptoms of GOO, such as nausea and vomiting, are reported in 11% to 50% of patients with pancreatic cancer at the time of diagnosis (DiMagno et al, 1999). For the optimal palliative treatment, it is important to determine the origin of these symptoms. The first cause is motility dysfunction of the stomach and duodenum secondary to tumor infiltration of the celiac nerve plexus (Thor et al, 2002) or probably dysfunction of the small bowel owing to tumor infiltration around the mesenteric artery. The second cause of GOO is mechanical obstruction of the duodenum from direct tumor ingrowth into the duodenum or secondary to compression of the duodenum by a tumor in the direct vicinity. At presentation, mechanical obstruction is reported in only approximately 5% of patients with pancreatic or periampullary tumors.

Surgical palliation should be performed only when GOO has a mechanical cause. When there is no mechanical cause, pharmaceutical treatment options should be investigated (Yeo et al, 1993). It is important to confirm mechanical GOO radiologically or endoscopically. Approximately 3% to 20% of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer eventually develop mechanical GOO (Espat et al, 1999; Lillemoe et al, 1999). In a review by Watanapa and Williamson (1992) that included 1086 patients, 17% developed mechanical GOO, and an additional gastrojejunostomy was performed on these patients. In patients who are found to have an unresectable tumor at laparotomy, a gastrojejunostomy, in addition to a biliary bypass, is often performed and is not associated with increased morbidity and mortality (see Table 63B.1).

Endoscopic duodenal stenting also is accepted as a nonsurgical palliative treatment of duodenal obstruction (Holt et al, 2004; Telford et al, 2004). In a multicenter study, the success rate after stent placement was 84%, and oral intake in patients with successful stent placement resumed for a median time of 146 days (Telford et al, 2004). Recently, a systematic review was performed to analyze medical outcome and costs of gastrojejunostomy and stent placement. No difference was found in technical success rate (96% vs. 100%), early and late major complications (7% vs. 6% and 18% vs. 17%, respectively), and persisting symptoms (8% vs. 9%). Hospital stay was longer after surgical gastrojejunostomy, 13 versus 7 days after stent placement. The mean survival time after gastrojejunostomy was 164 days versus 105 days after stenting. The authors concluded that a stent should be used for patients with a relatively short life expectancy, and gastrojejunostomy should be performed for patients with a prolonged prognosis (Jeurnink et al, 2007).

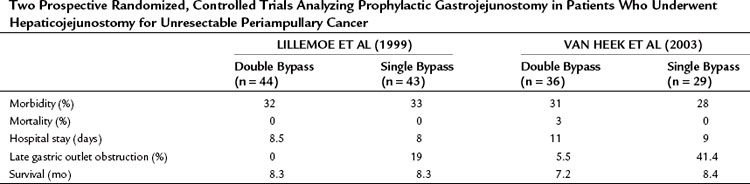

Among surgeons and gastroenterologists, it is debated whether a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy should be performed. This is an important topic because only 40% to 80% of patients with pancreatic cancer who initially undergo an exploratory laparotomy with the intention to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy undergo a resection (Alexakis et al, 2004; Kuhlmann et al, 2004; Pisters et al, 2001; Sohn et al, 1999). Two randomized controlled trials evaluated the role of a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy in patients who were found to have an unresectable periampullary or pancreatic tumor during exploratory laparotomy (Lillemoe et al, 1999; Van Heek et al, 2003). Lillemoe and colleagues (1999) analyzed 87 patients who were found to have an unresectable tumor and were believed to not be at risk for duodenal obstruction. These patients received either a prophylactic retrocolic gastrojejunostomy and a biliary (double) bypass or a biliary (single) bypass alone. Both groups also underwent a chemical splanchnicectomy during the laparotomy. The addition of a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy did not increase procedure-related mortality and morbidity rates and did not extend hospital stay (Table 63B.3). None of the patients who received a gastrojejunostomy developed late GOO during follow-up compared with 19% of patients who did not undergo a gastrojejunostomy in the initial procedure, which was a significant difference. No significant difference in survival was found between both groups.

Table 63B.3 Two Prospective Randomized, Controlled Trials Analyzing Prophylactic Gastrojejunostomy in Patients Who Underwent Hepaticojejunostomy for Unresectable Periampullary Cancer

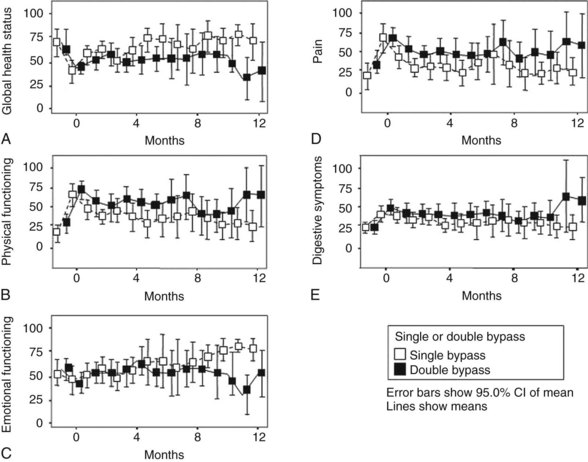

Van Heek and colleagues (2003) also randomly assigned patients found to have a resectable tumor during exploration to either a single bypass or a double bypass in a multicenter trial. The outcome of the interim analysis after 50% (n = 70) of the inclusion was comparable with the outcome of the study by Lillemoe and colleagues (1999), and it was decided to discontinue the trial. During follow-up, clinical GOO was diagnosed in 5.5% of patients after double bypass and in 41.4% of patients after single bypass, which was a significant difference (Fig. 63B.3). The study by Van Heek and colleagues (2003) also longitudinally evaluated the QOL of these two patient groups using the EORTC-C30 and Pan 26 questionnaires. Overall, no major differences were observed in the QOL between the two surgical treatment groups (Fig. 63B.4). After surgery, most QOL scores deteriorated temporarily and were restored to their preoperative levels within 4 months. This pattern of a temporary deterioration of the different domains of QOL score and restoration after a few months also was found in patients undergoing a Whipple procedure and was comparable to the temporary deterioration of QOL after bypass surgery (Nieveen van Dijkum et al, 2005).

The results of a recent meta-analysis also favor prophylactic gastroenterostomy. The chance of GOO during follow-up was significantly lower (OR, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.21; P < .001) with no difference in postoperative morbidity and mortality rates (Hüser, 2009). In these studies, endoscopic stenting of duodenal obstruction during follow-up was not attempted routinely, which could influence the outcome in the near future. A new trial should focus on nonsurgical palliation, including stenting of the common bile duct and the duodenum and adding a celiac plexus block by EUS versus the “optimal” surgical palliation described above, including the double-bypass procedure.

Pain Management

Another phenomena, such as neurogenic inflammation, well known from patients with chronic pancreatitis, could also lead to pain generation in this group of patients. These different mechanisms have been summarized nicely in a recent report on pain generation (di Mola & di Sebastiano, 2008). Initial pain management should be pharmacologic and should be composed of analgesics such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral or transdermic narcotic analgesics (Cruciani & Jain, 2008). Side effects of these drugs are frequently reported, however, and eventually pharmaceutical pain management alone may be insufficient (Caraceni & Portenoy, 1996). The next step is a celiac plexus nerve block, which was first described by Kappis in 1914. The nerve block interrupts the innervation of the pancreas and prevents painful stimuli from reaching the brain. This is a relatively straightforward procedure, but it can cause side effects, such as diarrhea and orthostatic hypotension, in approximately 40% of patients (Eisenberg et al, 1995). Currently, the celiac plexus block can be performed percutaneously, by EUS, or during laparotomy. Permanent paraplegia is uncommon (0.15%) but is the most dramatic complication of this procedure, which results from an infarct/occlusion of the art spinalis anterior (Abdalla & Schell, 1999).

Percutaneous Celiac Plexus Block

The percutaneous route to block the celiac plexus has been investigated extensively. It can be performed under fluoroscopic, CT, or US guidance. Multiple studies, mostly uncontrolled, have evaluated the accuracy and techniques of percutaneous celiac plexus block. In a meta-analysis of 24 publications that included 1145 patients treated with a percutaneous neurolytic celiac plexus block (NCPB) for cancer pain (63% pancreatic cancer), 70% to 80% of patients had long-lasting benefit from the procedure (Eisenberg et al, 1995).

Only a few randomized controlled trials on NCPB have been done (Ischia et al, 1992; Polati et al, 1998; Wong et al, 2004). The best evidence is in the most recent study by Wong and associates (2004), who randomly assigned 100 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer to receive either NCPB or a sham NCPB procedure. After the randomized procedure, both groups could receive systemic analgesic therapy according to the WHO guidelines. End points were pain relief, QOL, and survival. The major findings were that NCPB significantly improved pain relief in patients with pancreatic cancer compared with optimized analgesic therapy, but it did not affect QOL or survival. NCPB had no effect on the consumption of analgesics, and significantly more patients needed a rescue NCPB in the analgesic therapy group (10 vs. 3 patients; P = .01).

These results suggest that the application of an aggressive pain management protocol, regardless of NCPB, can effectively control pain, although NCPB can provide significantly better analgesia than optimized analgesic therapy alone. Polati and colleagues (1998) performed a small, randomized, controlled trial (n = 24) comparing percutaneous NCPB with pharmacologic therapy; mean analgesic consumption was lower, and drug-related side effects—constipation, nausea, and vomiting—were significantly less frequent in the group that underwent a nerve block. Ischia and colleagues (1992) randomized 61 patients to receive either a transaortic block, a classic retrocrural block, or a bilateral chemical splanchnicectomy. In 60% to 75% of patients, both techniques abolished pain until the patient’s death.

Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Celiac Plexus Block

More recently, EUS-guided fine needle injection therapy has been developed (Giovannini, 2004; Klapman & Chang, 2005), and various techniques have been described. Generally, 5 to 10 mL of 1% lidocaine and 15 to 20 mL of 95% alcohol are injected at two areas of the celiac trunk. Results from nonrandomized studies showed a significant reduction of pain in 85% to 90% of the patients. Studies and follow-up are limited, however, and trials comparing the efficacy of this endoscopic procedure with the other techniques should be performed.

Celiac Plexus Block During Surgery

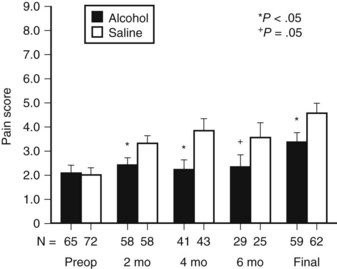

Celiac plexus block during surgery has been performed for many years. Lillemoe and colleagues (1993a) conducted a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial that compared a chemical splanchnicectomy during laparotomy with alcohol versus saline placebo. Chemical splanchnicectomy was performed perioperatively by injection of 20 mL of either 50% alcohol or saline solution on each side of the aorta at the level of the celiac axis. No differences were observed between the two groups concerning mortality rate, procedure-related complications, and hospital stay. Long-term complications and side effects were not investigated. Compared with the placebo group, alcohol injection significantly reduced the mean pain score for surviving patients at 2, 4, and 6 months (Fig. 63B.5). In the alcohol group, significantly more patients never reported pain (56% vs. 34%). However, the analgesic effect was not permanent: 10% of patients in the alcohol group required an additional percutaneous celiac axis block compared with 12% in the saline group. The time interval between the initial operative and additional percutaneous block varied significantly (11.8 ± 3.2 vs. 4 ± 1.1 months) in the alcohol group and saline group, respectively. Actuarial survival was improved in the subgroup of patients who reported significant preoperative pain and underwent a splanchnicectomy with alcohol (P < .001). The authors suggested that the difference could be caused by the progressive physical deterioration secondary to persistent pain, which eventually leads to impaired survival. These findings confirm other reports that state the presence of pain is associated with a poor prognosis (Kelsen et al, 1997).

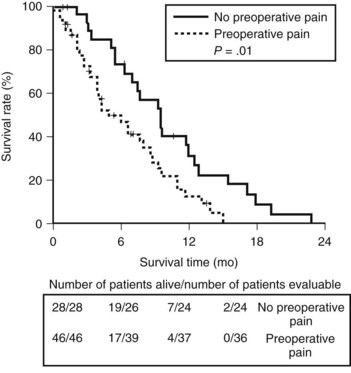

The Amsterdam group retrospectively analyzed pain in 74 patients who underwent a palliative bypass for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Van Geenen et al, 2002). The investigators found a significant difference in survival between patients who reported preoperative pain and patients who did not (4.9 vs. 9.5 months, respectively; P = .01; Fig. 63B.6). The association of persistent pain with a more advanced stage of the tumor could also explain this difference.

Another strategy to palliate pain is the thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. A bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy or a unilateral left-sided thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy can be performed. Ihse and colleagues (1999) performed a prospective study analyzing the follow-up of patients with pancreatic cancer (n = 23) or chronic pancreatitis (n = 21) who underwent a bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. Within 1 week, the average pain scores were reduced by more than 50% and remained stable throughout the follow-up period of 4 months. Four patients (9%) required a thoracotomy because of a bleeding complication. Leksowski (2001) showed adequate and consistent pain relief in 26 patients who underwent a unilateral splanchnicectomy. Follow-up was also limited to 6 months, and recurrent pain after that period was not analyzed.

Radiotherapy can also be applied to reduce pancreatic cancer pain. It may take several weeks before pain relief is achieved, however, and side effects are common. Most studies are limited because of small patient numbers and poor pain assessment methods. Ceha and colleagues (2000) investigated the feasibility of high-dose conformal radiotherapy (70 to 72 Gy, 35 to 36 fractions) in 44 patients with nonresectable pancreatic cancer. Pain relief was experienced in 68% of patients, with a median duration of 6 months to pain progression.

Pancreatoduodenectomy For Palliation

Several reports have discussed the indications to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy as a palliative treatment option (Fusai et al, 2008; Gouma et al, 1999; Köninger et al, 2008; Lavu et al, 2009; Lillemoe et al, 1996; Reinders et al, 1995; Schniewind et al, 2006). This controversial question results from the observation of reduced morbidity and mortality associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in high-volume centers (Cameron et al, 1993; Kuhlmann et al, 2004; Lillemoe et al, 1996). This decreased mortality rate is partly due to improved management of severe complications (de Castro et al, 2005), but mainly to a hospital volume effect (Alexakis et al, 2004; Cameron et al, 1993; Gouma et al, 2000).

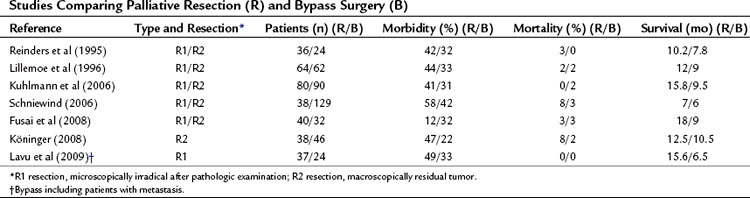

Frequently, the term palliative resection has been used to describe patients in whom the palliative resection was regarded as a macroscopically radical resection, which appeared to be microscopically nonradical after pathologic examination, a so-called R1 resection (Table 63B.4). Although the resection was undertaken with a curative intention, it can be considered palliative (Fig. 63B.7). In this case, the resection is called palliative in retrospect. The percentage of these patients from cohort studies depends heavily on the quality of the pathology examination of the specimen. It is debatable whether these patients should be included, if the role of a palliative resection per se is discussed, because these patients underwent a resection with a curative intent. The term palliative resection probably should be used only for R2 resections, those with macroscopically residual tumor. In a few of these situations, the tumor is found to be nonresectable after a point of no return (e.g., after transection of the pancreatic neck), or resection is required because of preoperative tumor bleeding. As a result of improved staging strategies by CT and MRI, and the nonsurgical management of bleeding by selective embolization, this indication is limited in current practice (Alexakis et al, 2004; de Castro et al, 2005; Phoa et al, 2000; WHO, 2002). However, some authors consider this an optimal palliative treatment (Köninger et al, 2008). No prospective studies in which a resection was performed or planned as a palliative procedure after adequate preoperative staging showed advanced disease leading to R2 resection.

The benefit of surgical resection in the subset of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, including those with vascular ingrowth in portal vein and/or mesenteric vein, should be balanced against the potential benefits and complications of palliative chemoradiotherapy. Because no randomized controlled trials have been done, a decision analysis was provided comparing the survival after pancreatic resection, including portal vein resection, for locally advanced pancreatic cancer with survival after palliative chemoradiotherapy. It was concluded that surgical resection might confer a survival advantage over palliative chemoradiotherapy in selected patients with presumed local venous ingrowth. However, it was also found that if the probability of an R1 or R2 resection is greater than 77%, resection is no longer the favored strategy (Abramson et al, 2009). Another group of patients is a very small, well-selected group in which (palliative) resection is performed: patients with metastatic disease, mainly patients with solitary (small) liver metastasis, limited peritoneal metastasis, or interaortacaval/intermesenteric lymph node metastasis. A few small studies have been published that show combined pancreatic resection with hepatic resection is technically possible and relatively safe (Gleisner et al, 2007; Shrikhande et al, 2007). These studies showed no long-term survival, and it might be questioned whether survival in this highly selected group of patients is better compared with that of patients who receive other palliative procedures. The study from Hopkins (Fleiser, 2007) showed similar overall survival of the combined resection, compared with palliative bypass alone, but increased morbidity and hospital stay.

Laparoscopic Palliation

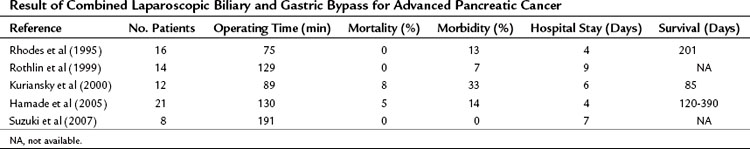

Although a cholecystojejunostomy as a biliary bypass is considered to be less suitable because of the higher incidence of recurrent jaundice, this strategy is easier and safer compared with a hepaticojejunostomy (see Chapter 29). To prevent short-term obstruction of the cholecystojejunostomy, the tumor status in relation to the cystic junction anatomy always should be assessed by performing cholangiography; otherwise, a laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and bypass is indicated. The available data from five relatively small studies showed that laparoscopic double bypass can be performed safely with acceptable morbidity and low mortality rates (Table 63B.5). The long-term follow-up concerning recurrent jaundice and GOO is highlighted only briefly in these studies, however (Hamade et al, 2005; Kuriansky et al, 2000; Rhodes et al, 1995; Rothlin et al, 1999; Suzuki et al, 2007). As previously mentioned, new endoscopic techniques, including duodenal stenting for GOO (Mittal et al, 2004; Nassif et al, 2003; Wong et al, 2002), should be compared with new, minimally invasive laparoscopic approaches.

Abdalla EK, Schell SR. Paraplegia following intraoperative celiac plexus injection. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:668-671.

Abraham NS, et al. Palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective trial examining impact on quality of life. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:835-841.

Abrams RA, et al. Combined modality treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreas cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1751-1756.

Abramson MA, et al. Surgical resection versus palliative chemoradiotherapy for the management of pancreatic cancer with local venous invasion: a decision analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:26-34.

Adham M, et al. Long-term survival (5-20 years) after pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a series of 30 patients collected from 3 institutions. Pancreas. 2008;37:352-357.

Alexakis N, et al. Current standards of surgery for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1410-1427.

Andersen JR, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic endoprosthesis versus operative bypass in malignant obstructive jaundice. Gut. 1989;30:1132-1135.

Bemelman WA, et al. Diagnostic laparoscopy combined with laparoscopic ultrasonography in staging of cancer of the pancreatic head region. Br J Surg. 1995;82:820-824.

Bjerregaard JK, et al. Long-term results of concurrent radiotherapy and UFT in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:226-230.

Birkmeyer JD, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117-2127.

Bornmann PC, et al. Prospective controlled trial of transhepatic biliary endoprosthesis versus bypass surgery for incurable carcinoma of head of pancreas. Lancet. 1986;1:69-71.

Callery MP, et al. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1727-1733.

Cameron JL, et al. One hundred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without mortality. Ann Surg. 1993;217:430-435.

Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. Pain management in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78:639-653.

Ceha HM, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of high dose conformal radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:2222-2229.

Crippa S, et al. Quality of life in pancreatic cancer: analysis by stage and treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:783-793.

Cruciani RA, Jain S. Pancreatic pain: a mini review. Pancreatology. 2008;8:230-235.

de Castro SM, et al. Surgical management of neoplasms of the ampulla of Vater: local resection or pancreatoduodenectomy and prognostic factors for survival. Surgery. 2004;136:994-1002.

de Castro SM, et al. Delayed massive hemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery: embolization or surgery? Ann Surg. 2005;241:85-91.

Di Fronzo LA, et al. Unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: correlating length of survival with choice of palliative bypass. Am Surg. 1999;65:955-958.

DiMagno EP, et al. AGA technical review on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1464-1484.

di Mola FF, di Sebastiano P. Pain and pain generation in pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:919-922.

Eisenberg E, et al. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for treatment of cancer pain: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:290-295.

Espat NJ, et al. Patients with laparoscopically staged unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma do not require subsequent surgical biliary or gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:649-655.

Friess H, et al. The role of diagnostic laparoscopy in pancreatic and periampullary malignancies. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:675-682.

Fusai G, et al. Outcome of R1 resection in patients undergoing pancreatico-duodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1309-1315.

Giovannini M. Ultrasound-guided endoscopic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:183-200.

Gleisner AL, et al. Is resection of periampullary or pancreatic adenocarcinoma with synchronous hepatic metastasis justified? Cancer. 2007;110:2484-2492.

Gouma DJ, et al. Are there indications for palliative resection in pancreatic cancer? World J Surg. 1999;23:954-959.

Gouma DJ, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786-795.

Greenlee RT, et al. Cancer statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7-33.

Gudjonsson B. Carcinoma of the pancreas: critical analysis of costs, results of resections, and the need for standardized reporting. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:483-503.

Gudjonsson B. ancreatic cancer: survival, errors and evidence. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1379-1382.

Hamade AM, et al. Therapeutic, prophylactic, and preresection applications of laparoscopic gastric and biliary bypass for patients with periampullary malignancy. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1333-1340.

Holt AP, et al. Palliation of patients with malignant gastroduodenal obstruction with self-expanding metallic stents: the treatment of choice? Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:1010-1017.

Hüser N. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prophylactic gastroenterostomy for unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:711-719.

Ihse I, et al. Bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy: effects on pancreatic pain and function. Ann Surg. 1999;230:785-790.

Ischia S, et al. Three posterior percutaneous celiac plexus block techniques: a prospective, randomized study in 61 patients with pancreatic cancer pain. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:534-540.

Jeurnink SM, et al. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18.

Kaassis M, et al. Plastic or metal stents for malignant stricture of the common bile duct? Results of a randomized prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:178-182.

Kappis M. Erfahrungen mit Lokalanästhesie bei. Bauchoperationen. Ver Dtsch Geselsch Chir. 1914;43:87-89.

Kelsen DP, et al. Pain as a predictor of outcome in patients with operable pancreatic carcinoma. Surgery. 1997;122:53-59.

Klapman JB, Chang KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle injection. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15:169-177.

Köninger J, et al. R2 resection in pancreatic cancer—does it make sense? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:929-934.

Kuhlmann KF, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:549-558.

Kuriansky J, et al. Simultaneous laparoscopic biliary and retrocolic gastric bypass in patients with unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:179-181.

Lavu H, et al. Margin positive pancreaticoduodenectomy is superior to palliative bypass in locally advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1937-1946.

Leksowski K. Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy for control of intractable pain due to advanced pancreatic cancer. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:129-131.

Lesurtel M, et al. Palliative surgery for unresectable pancreatic and periampullary cancer: a reappraisal. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:286-291.

Lillemoe KD, et al. Chemical splanchnicectomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1993;217:447-455.

Lillemoe KD, et al. Current status of surgical palliation of periampullary carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:1-10.

Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: does it have a role in the palliation of pancreatic cancer? Ann Surg. 1996;223:718-725.

Lillemoe KD, et al. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322-328.

Mann CD, et al. Combined biliary and gastric bypass procedures as effective palliation for unresectable malignant disease. Aust N Z J Surg. 2009;79:471-475.

McMahon PM, et al. Pancreatic cancer: cost-effectiveness of imaging technologies for assessing resectability. Radiology. 2001;221:93-106.

Mittal A, et al. Matched study of three methods for palliation of malignant pyloroduodenal obstruction. Br J Surg. 2004;91:205-209.

Müller MW, et al. Factors influencing survival after bypass procedures in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg. 2008;195:221-228.

Nakakura EK, Warren RS. Palliative care for patients with advanced pancreatic and biliary cancers. Surg Oncol. 2007;16:293-297.

Nassif T, et al. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expandable metallic stents: results of a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2003;35:483-489.

Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, et al. Laparoscopic staging and subsequent palliation in patients with peripancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2003;237:66-73.

Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, et al. Quality of life after curative or palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92:471-477.

Park RW, et al. Surgical biliary bypass for benign and malignant extrahepatic biliary tract disease. Br J Surg. 1997;84:488-492.

Phoa SS, et al. CT criteria for venous invasion in patients with pancreatic head carcinoma. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:1159-1164.

Pisters PW, et al. Laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:325-337.

Polati E, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind trial of neurolytic coeliac plexus block in patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:199-201.

Rappaport MD, Villalba M. A comparison of cholecysto- and choledochoenterostomy for obstructing pancreatic cancer. Am Surg. 1990;56:433-435.

Reinders ME, et al. Outcome of microscopically nonradical, subtotal pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s resection) for treatment of pancreatic head tumors. World J Surg. 1995;19:410-414.

Rhodes M, et al. Laparoscopic biliary and gastric bypass: a useful adjunct in the treatment of carcinoma of the pancreas. Gut. 1995;36:778-780.

Rothlin MA, et al. Laparoscopic gastro- and hepaticojejunostomy for palliation of pancreatic cancer: a case controlled study. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1065-1069.

Sarfeh IJ, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of cholecystoenterostomy and choledochoenterostomy. Am J Surg. 1988;155:411-414.

Sener SF, et al. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985-1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:1-7.

Shepherd HA, et al. Endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis in the palliation of malignant obstruction of the distal common bile duct: a randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1166-1168.

Shrikhande SV, et al. Pancreatic resection for M1 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:118-127.

Singh S, et al. Palliative surgical bypass for unresectable periampullary carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:308-312.

Smith AC, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bile duct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655-1660.

Sohn TA, et al. Surgical palliation of unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma in the 1990s. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:658-666.

Suzuki O, et al. Laparoscopic modified Devine exclusion gastrojejunostomy as a palliative surgery to relieve malignant pyloroduodenal obstruction by unresectable cancer. Am J Surg. 2007;194:416-418.

Taylor MC, et al. Biliary stenting versus bypass surgery for the palliation of malignant distal bile duct obstruction: a meta-analysis. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:302-308.

Telford JJ, et al. Palliation of patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction with the enteral Wallstent: outcome from a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:916-920.

Thor PJ, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma-induced changes in gastric myoelectric activity and emptying. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:268-270.

Tilleman EH, et al. Limitation of diagnostic laparoscopy for patients with a periampullary carcinoma. Eur J Surg. 2004;30:658-662.

Van der Gaag NA, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:129-137.

Van Geenen RC, et al. Pain management of patients with unresectable peripancreatic carcinoma. World J Surg. 2002;26:715-720.

Van Heek NT, et al. The need for a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy for unresectable periampullary cancer: a prospective randomized multicenter trial with special focus on assessment of quality of life. Ann Surg. 2003;238:894-902.

van Wagensveld BA, et al. Outcome of palliative biliary and gastric bypass surgery for pancreatic head carcinoma in 126 patients. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1402-1406.

Watanapa P, Williamson RC. Surgical palliation for pancreatic cancer: developments during the past two decades. Br J Surg. 1992;79:8-20.

Weber A, et al. Self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for palliative treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2009;38:e7-e12.

Wong GY, et al. Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1092-1099.

Wong YT, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to pancreatic cancer: surgical vs endoscopic palliation. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:310-312.

World Health Organization, 2002: National Cancer Control Programmes: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. Geneva.

Yeo CJ, et al. Erythromycin accelerates gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1993;218:229-237.