CHAPTER 81 Pain Dysfunction Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Previous chapters of this book have dealt largely with the management of specific traumatic conditions and surgical reconstructive principles involved in the treatment of disorders of the elbow articulation. Necessarily, inferred but often understated in the discussion of these subjects is the inherent and inseparable consequence of some degree of pain experienced by normal individuals. Pain is defined as the perception of an unpleasant sensation that is generally localized to a specific anatomic region in response to a noxious stimulus (trigger) capable of producing potential or actual tissue damage.19,59,73 Although unpleasant, the perception of acute pain serves an important physiologic function because it elicits a protective behavioral response outwardly noted as retraction from the noxious stimulus, followed by a transitory period of protection and guarding of the injured part.37 Inseparable from the experience of acute pain is an individually variable emotional response that is dependent on the physiologic, psy-chological, cultural, and socioeconomic state of the person.3,29,141

Both postoperative pain and the temporary residual pain of recent injury are physiologic (functional) variants of acute pain.63,141 Orthopedic surgeons generally have considerable clinical experience in dealing with a normal acute pain response and its variants by proceeding first with proper care of the injured part, administration of appropriate analgesics, and offering of emotional support and counseling. However, if during the course of initial treatment or the rehabilitation period a patient’s complaint of reported pain is judged to be extreme with respect to the known degree of tissue damage, or if the pain is abnormally prolonged, or the location and quality are poorly defined or nonspecific, then the possibility of a dysfunctional pain disorder must be considered when all plausible functional causes (e.g., compartment syndrome) have been eliminated.89 The presentation of a patient’s dysfunctional pain response is most assuredly an unwelcome and worrisome complication, and often poses considerable challenges to the subsequent successful treatment and resolution of the presenting musculoskeletal problem. Moreover, following the recognition of dysfunctional pain, there is often a reasonable degree of consternation and possible indecision regarding the implementation of appropriate measures of management. Reasons for such indecision are well founded, because often the historical details, nature, and presentation of any patient’s dysfunctional pain pattern are individually variable, and clinical expertise is difficult to achieve in normal practice. Furthermore, until relatively recently, the amount of clinically relevant information on abnormal pain disorders within the musculoskeletal literature has been sparse, most often made up of anecdotal case studies.29 The more detailed descriptive reports that are present in the literature have unfortunately been collectively categorized under a confusing array of terms (Box 81-1).

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The first of the terms in Box 81-1, causalgia (Gk., “burning”), was initially defined by S. Weir Mitchell, a Union surgeon during the Civil War.96 Mitchell eloquently described a syndrome characterized by the onset of unrelenting intense, often burning, pain of an affected extremity, hypersensitivity, vasomotor disturbances, and the overzealous guarding of the injured part. Mitchell also described the consistent and profound psychological changes noted in affected patients, most of whom had sustained direct rifle ball wounds to major peripheral nerves of the upper extremity.1,2,96,124,142 After the war, Mitchell, Bernard, Leriche, and other noted physicians of the time, continued investigation of this and related pain disorders, primarily focused on the pathophysiologic basis for the observed autonomic nervous system disturbances, whereas other resear-chers proposed theories for a psychogenic basis of causalgia.*

Most of the early investigative information from the study of causalgia and related disorders was derived from the evaluation of patients who had often sustained major injuries to the involved extremity. In 1953, Bonica proposed the term reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD) to define an abnormal pain syndrome clinically similar to causalgia that required sympathetic autonomic dysfunction as a major feature but was associated with an extremely varied range of etiologic factors.1,10,115,135 Associated events included both major and minor trauma, multiple types of surgical procedures, and repetitive occupational activities, and a collection of physiologically unrelated systemic diseases and idiopathic case examples.1,2,10,11,109,115,118

DEFINITION AND TERMINOLOGY

It is perhaps largely due to the confusing diversity of precipitating etiologic factors proposed by Bonica, as well as his prominent role in research in this area and the lack of any reproducible laboratory models to explain either a pathophysiologic relationship or the relative importance of these factors to the clinical development of RSD, that the term has been badly misused in the literature.2,4,29,120,141 Indeed, the term RSD has unfortunately evolved both in general clinical correspondence and in the medical literature to stand as a generic term for the presentation of any abnormal pain presentation or prolonged extremity dysfunction whether or not autonomic dysfunction exists.29 The unfortunate end result of the continued clinical confusion and the generic use of the term RSD with respect to treatment implementation is that currently no consistent agreement exists regarding diagnostic criteria, natural history, and psychological factors involved in the syndromes listed in Box 81-1. These unresolved issues have often resulted in arbitrary clinical evaluation and anecdotal treatment protocols.29,141 More recently, several authors have stressed the importance of distinguishing whether the sympathetic nervous system is involved by subcategorizing abnormal pain syndromes as sympathetically maintained pain or as sympathetically independent pain.94,114

When a critical review of the literature is undertaken comparing the diagnostic criteria of each of the syndromes listed in Box 81-1 irrespective of the proposed etiologies or pathophysiologic factors, all clearly have two common denominators: an abnormal pain response and dysfunction of the affected extremity.3,29 From the recognition of this commonality of abnormal pain and extremity dysfunction among all the various pain syndromes and with the intent to rectify the perpetuation of the use of RSD as a generic label, Dobyns29 and Amadio3 have recently recommended a more general term, pain dysfunction syndrome (PDS), to define such disorders. The use of the term PDS has several advantages. First, it is both clinically descriptive and sufficiently broad so as to encompass the diversity of possible precipitating factors and removes the contingency that sympathetic nervous system dysfunction exists in all cases of an abnormal pain presentation, which was necessarily implicit in the generic use of the term RSD.29

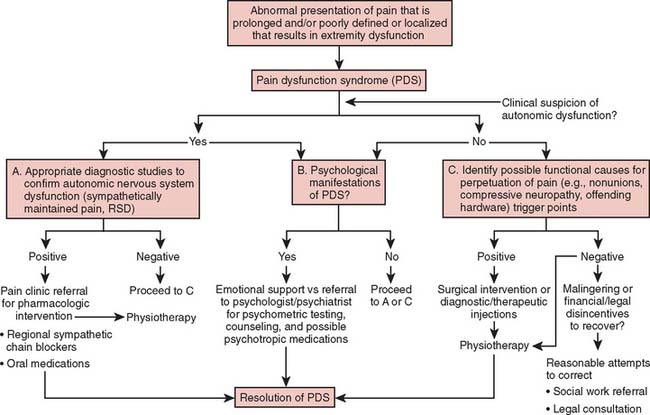

By using PDS as a clinically descriptive label, the treating physician may then proceed without any nosologic hindrances to objectively differentiate, order, and subcategorize all the involved factors of a PDS into specific components.29 These components include the physiologic characteristics of the injury and other sources of pain, any psychological manifestations, and the presence or absence of autonomic dysfunction.3 By proceeding in this logical fashion, the design of an effective and nonarbitrary treatment protocol can then be implemented (Fig. 81-1).

PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN

Before any further meaningful discussion on the clinical aspects of an abnormal pain response as a component of PDS can proceed, it is necessary to have an understanding of normal pain physiology. The sensation of normal acute pain begins with the interaction of a physical trigger (mechanical, thermal, and chemical) on a region of the body. Peripheral sensory nociceptors and mechanoreceptors are activated by the triggering event and transduce the physical energy into an electrochemical stimulus, which is then relayed proximally along the peripheral nerve via myelinated (Ad and Ab) and unmyelinated (C) fibers to synapse on wide dynamic range neurons of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.4,53,81,93,114,136,140,141 Further proximal propagation of the stimulus is then transmitted through the spinothalamic and spinoreticular pain pathways to central pain centers, which are located primarily within the midbrain, thalamus, and frontal cortex.37,140 Modulation of nociceptive stimulation occurs via central descending pathways and peripheral chemical factors.14 At the site of injury, should the physical trigger be of sufficient magnitude to produce tissue damage, local chemical modulators (hydrogen, potassium, bradykinin, serotonin, prostaglandins,16 substance P) are released from the damaged cells, which further activate and sensitize the peripheral receptors and focally produce the characteristic signs of edema, vasodilation, hyperpathia, and allodynia.111,141 Provided that no ongoing or irreversible tissue damage occurs, both the cognitive perception of pain and the physiologic signs and symptoms of the acute pain dystrophic response subside.37,53,140

The failure of any feature of the acute pain dystrophic response to resolve normally becomes a matter of clinical concern. In some cases, the abnormal persistence of pain may have a functional etiology, as when an unrecognized infection, synovial inflammation, ischemia, or nerve entrapment exists.3 Systemic factors such as rheumatologic disorders, endocrine or metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetic neuropathy), and the collagen vascular diseases can alter normal pain sensation as well as prolong the natural resolution process.3,26,27,37 When all functional causes have been excluded, of particular concern is any reported change in the intensity, quality, and location of the pain sensation and the persistence or dissemination of focal edema, color changes, and thermoregulatory adaptations that are seen initially as part of the acute pain dystrophic response.

It has been well established both clinically and experimentally that the sympathetic nervous system can contribute to the pathogenesis of RSD and other related pain syndromes.2,10,11,77,78,130,131 Evidence for this has been demonstrated by the fact that regional anesthetic blockade or interruption of the sympathetic nervous system produces relief of the pain of RSD and that electrical stimulation of the sympathetic chain exacerbates the pain in many patients suspected of having a sympathetically maintained pain.37 Further evidence that the sympathetic nervous system contribution to the genesis and maintenance of certain abnormal pain syndromes is indeed a pathologic process is demonstrated by the observation that in normal persons when sympathetic outflow is electrically stimulated, no painful sensation is produced, nor does regional sympathetic blockade alter normal pain sensation.37 Despite these and other clinical and experimental observations, there as yet exists no definitive laboratory model that explains fully how the sympathetic nervous system alters, produces, or maintains the pain of RSD and related disorders, although numerous plausible hypotheses have been proposed.1,2,33,67,77,101,111,114,127 Collectively, these hypotheses can be grouped into either adaptive central nervous system dysfunction processes or peripheral end organ and receptor abnormalities.13

CLASSIFICATION

Several classification schemes for RSD have been described in the literature.1,74 In general terms, the more accepted classification schemes have been based on either the natural history of signs and symptoms of the disorder or on the type and magnitude of the precipitating injury.71–74103 Lankford’s classification, based on injury type, proposes two distinct forms of sympathetic dysfunction (Box 81-2). The first, causalgia, results from direct nerve injury and is further subcategorized into either major or minor causalgia depending on whether the injury is due to a mixed motor/sensory or a sensory nerve, respectively. Traumatic dystrophy, the second type, is similarly subcategorized into major and minor subtypes. A minor traumatic dystrophy generally results from a less severe injury such as a sprain or contusion, whereas a major traumatic dystrophy results from a more extensive injury such as a fracture.3,34,73,74 Amadio and others have pointed out that the use of this type of classification scheme can be both confusing and imprecise, because some examples of RSD have no clear traumatic etiology and some minor causalgia may prove to be more disabling than a major causalgia.3

The second type of classification scheme for RSD is based on the natural history of the clinically observed physiologic, morphologic, and functional changes observed in untreated RSD.115,128 The Steinbrocker classification recognizes three distinct stages: (1) the acute stage (0 to 3 months), (2) the dystrophic stage (3 to 6 months), and (3) the atrophic stage (6 months and beyond) (Table 81-1).128 In the earlier phases, the pain is often burning and more focal than diffuse, and the associated edema, vasomotor, and thermoregulatory dysfunction are usually prevalent. In the later stages, the pain is more constant and poorly localized. Muscle atrophy, joint stiffness, or contractures may develop, along with subcutaneous fibromatous organization and cyanosis of the skin. End-stage RSD is characterized by the appearance of more permanent changes of the skin, blood vessels, and joints (ankylosis).37,115 It is important to recognize that RSD is a dynamic process, and although the previously mentioned stages accurately describe the symptomatic and pathophysiologic changes in general, in any individual a considerable temporal variability may occur in the development of the characteristic signs and symptoms, and subtle and partial manifestations are generally the rule rather than the exception. Therefore, no classification scheme is wholly satisfactory.3,37 In view of this, recently (similar to Dobyns) Boas8 has recognized the importance of a clinically descriptive classification scheme, and the term has been proposed and is gaining wider acceptance in the literature (Box 81-3).

TABLE 81-1 Classification of Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy by Temporal Factors (Steinbrocker)

| Type | Duration (months) |

|---|---|

| Acute | <3 |

| Dystrophic | 3–6 |

| Atrophic | >6 |

BOX 81-3 Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

| Type I | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy |

| Abnormal pain, dysfunction of the extremity, autonomic nervous system abnormalitites, and recognizable dystrophic clinical features without direct nerve injury | |

| Type II | Causalgia |

| Abnormal pain, dysfunction of the extremity, autonomic nervous system abnormalities, and recognizable dystrophic clinical features with a known nerve injury? | |

| Type III | Other pain dysfunction syndromes |

PSYCHOLOGY OF PAIN AND DYSFUNCTION

In the previous section, the sensorineural mechanisms involved in the sensation of acute pain were outlined. These mechanisms, however, do not exist in isolation. The perception of a painful stimulus always yields an affective or emotional component that is individually variable and complex.27,29,50 In the treatment of patients with PDS, the psychological component of the disorder may be pronounced and may evolve into the dominant clinical feature.29

The Psyche

Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss at length the multiple theories of how the psyche may produce changes on the soma, in the past, considerable clinical emphasis has been placed on the probability that there are definite psychogenic causes for some chronic pain disorders, particularly RSD.* Supporting the notion of a psychogenic basis for these disorders (even in less overt PDS) is that commonly a considerable disparity exists between the physical examination and the patient’s degree of fear, anxiety, and the reported degree of discomfort.37,50,51,118 In the past, patients were variously described as “hysterical,” “emotionally labile,” “dependent,” “unstable,” “depressed,” and having “vulnerable, brittle autonomic nervous systems.”24,30,58,71,95,99 Such descriptive psychological assessments imply that a premorbid personality or even psychoses may exist. What is clear from review of these early accounts is that these psychological assessments were largely the result of opinion rather than based on psychological testing.50,88,126 Several studies on RSD and other chronic pain syndromes, however, convincingly conclude that the observed personality and behavior changes are likely the consequence of the state of prolonged suffering rather than a manifestation of a pre-existing personality or psychological disorder.50,118,120,126,129,139 This is not to imply that some understandable emotional and psychological disturbances can occur in any individual living with chronic pain.29,32,37,41,50 Most frequently reported are persistent anxiety, reactive depression, dependency, and somatic preoccupation, all of which can impede the resolution of a PDS.29,37

In the process of identifying the psychological components of a PDS, one must differentiate from certain bona fide psychopathologic syndromes that often have as common features decreased pain tolerance or increased pain susceptibility or both; these are somatization disorder, conversion disorder, malingering, and factitious injury disorder.3,4,29,37,38,40 Patients with a somatization disorder often present with chronic pain as well as a history of recurrent multiple somatic complaints (at least 12) of long duration but for which no physical diagnosable disorder can be found.4,37,38 These patients are convinced that they are seriously ill and are not deterred by the evidence of normal test results. The disorder is generally more common in women and usually begins during adolescence. Common complaints are chronic pain and weakness of the extremities, nausea, amnesia, shortness of breath, and fainting spells.3,4,38

Conversion disorder, formerly called hysterical neurosis, like somatization disorder is also more common in women and usually presents with a history of chronic intermittent pain, the source of which is not medically identifiable.4,38 Other common symptoms are pseudoparalysis, nonanatomic sensory loss, and blindness.145 Posturing of the hand and upper extremity is frequently observed, the persistence of which may result in contracture.4,29 Differing from somatization disorder, the onset of a conversion disorder is usually more sudden and, when identifiable, the physical manifestations of the disorder occur unconsciously in reaction to a disturbing psychological conflict.4,29,38

Other identifiable syndromes in which complaints of pain are commonly associated include major depression (endogenous depression), hypochondriasis, factitious injury, and malingering.4,38 Major depression may be suspected by the characteristic dysphoric mood, sense of hopelessness, and vegetative symptoms (sleep alterations, poor appetite, fatigue), and often there is a preoccupation with pain, disease, and death.4,37,38,61,62 Hypochondriasis may be a symptom of major depression or may exist as a separate disorder characterized by a pervasive conviction that various imagined symptoms including pain are indicative of impending disease.3,4,38,61,62 Malingering is the conscious willful act of misrepresentation of symptoms of illness to avoid obligation or is contrived for secondary monetary gain. Factitious injury when secondary gain is identifiable represents a form of malingering.3,4

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Finally, in the process of distinguishing the psychic components of a PDS, we, as orthopedic surgeons, are perhaps especially aware of our society’s current socioeconomic and legal factors that may both produce and perpetuate the development of the various psychological components. Workers’ compensation laws, disability programs, and pending accident litigation all provide convincingly powerful disincentives to recover from injury.37,50,52,146 Nonetheless, we must remain cognizant that most patients present initially with legitimate claims of an injury and thus have functional reasons for their pain. Oftentimes our clinical suspicions of a contrived disincentive to return to useful activity may be the manifestation of the patient’s unwitting learned behavior that develops during the course of a prolonged rehabilitation from serious injury because there may be significant emotional, familial, legal, and financial rewards for the continuance of disability.33,144 These factors over time may then eventually overshadow some previously held good intentions to return to employment or obligation.18,37,39 Early settlement of compensation claims in such instances has been shown to have a positive effect on the overall recovery from a PDS.50,141,146

PATIENT PRESENTATION

HISTORY

The historical details of the events of the initial injury, if one is identifiable, including the mechanism and site of injury as well as the patient’s recollection of the intensity and subjective quality of the initial pain and extent of extremity dysfunction, are important facts.29 Details of the initial treatment and all subsequent treatment regimens are noted so as to establish the patient’s assessment of the effectiveness of previous treatment and should be compared with information in the medical records. Moreover, the patient’s recollection of any signs or symptoms suggestive of autonomic dysfunction or a sympathetically maintained pain are noted and compared with the recorded data.

A thorough investigation of the patient’s work history, family setting, and job satisfaction is necessary to fully investigate the patient’s assessment of how the injury and present dysfunction has affected his or her family life, employment, and future goals to gain insight into the emotional and psychological manifestations of the PDS.5,37,50 In related terms, documentation of any past or ongoing psychiatric treatment or present substance abuse, including use of prescribed medications, may be relevant.50 Finally, details of past medical history are taken to determine the existence of any systemic diseases that may contribute to the presentation or prolongation of chronic pain.3

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Often the physical examination of a patient with a PDS is difficult to perform secondary to the patient’s degree of discomfort and level of anxiety. The physical examination begins with the observation of any pertinent visible signs. If an injury was sustained, the examiner should note the patient’s posture and degree of protection of the injured part, the nature and extent of any wounds or surgical scars, the degree of edema, the presence of atrophy, and the presence of any characteristic signs of autonomic dysfunction, including circulatory differences, abnormal sweat patterns, alterations of hair growth and skin trophic changes. Following this, an orderly physical examination of the extremity is undertaken: the location of the pain along with the presence of any spasm or cocontraction is recorded, and range of motion, reflexes, motor strength, and sensibility are evaluated. When pertinent, assessment of fracture reduction and healing is noted, along with any associated joint swelling or synovitis as possible sources of ongoing pain (triggers). Provocative maneuvers are performed to document any signs of a peripheral nerve injury or presence of a compressive neuropathy. After both extremities have been allowed to equilibrate to room temperature, a gross estimation of any thermal abnormality about the affected extremity can be compared with the contralateral side to assess for thermoregulatory dysfunction. When thermal differences are noted, a more precise measurement can be made with special skin thermometers.64,65

Trigger Points

Dobyns has observed that musculoskeletal trigger points and irritability about peripheral nerves (particularly sensory cutaneous branches) are commonly found during the physical examination of patients with a PDS.3,29 Musculoskeletal trigger points are infrequently discussed in the orthopedic literature but are described often in those medical fields dealing with the treatment of chronic pain.29,37,41,47,54,90,91 Their etiology, however, remains controversial.37,42 Trigger points can be recognized as localized areas of tenderness that are most often found about the origin and insertion of muscles, tendons, and ligaments and along fascial planes and about capsular structures. They may or may not be anatomically related to the site of the original injury and often persist after the injury has healed and thus may perpetuate dysfunction.3,29,37 Irritability along cutaneous nerves is another common clinical problem found in the evaluation of PDS and is often secondary to trauma, surgical procedures, and improper application of casts and is associated with prolonged focal edema. Like musculoskeletal trigger points, nerve irritability can persist for long periods and thus act as a continued source of pain.84

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In addition to the findings obtained from the physical examination, certain diagnostic tests should be ordered to provide further objective information. Current plain radiographs of the involved extremity are obtained, often with comparison views of the contralateral extremity, to detect any differences in radiographic bone density.15,43,46,56,64,68–70 When indicated, other studies including arthrograms, tomograms, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies may yield useful information.3,35,43,84 Radionuclide imaging may confirm a previous diagnosis or can reveal previously unforeseen problems, as noted by localized increased radioisotope uptake.3,29,64,66,68–70 The three-phase bone scan technique has proven to be a particularly useful diagnostic tool in the evaluation of RSD, with a reported high degree of specificity in untreated cases.3,67–70,85

Other diagnostic tests for RSD and autonomic dysfunction have been described, including quantitative sweat production (Q-SART Low), dynamic vasomotor reflex assessment, and cold stress thermoregulatory capacity, all of which may add diagnostic information.3,36,48,64,83 The usefulness of thermography (infrared telethermometry) as a diagnostic test for RSD is controversial.75,105–107,119,135 Although all of these ancillary diagnostic tests may be necessary in certain case examples, the response to sympathetic blockade remains the single most useful and preferred test for the establishment of the diagnosis of RSD.3,76,78,97,102,104,116,117

As previously stated, the psychological aspects of a PDS are variable both in degree and in presentation. To objectively assess the psychic manifestations of the disorder, examiners have traditionally used several standard personality, psychometric, and pain quantitation tests to evaluate patients suffering from chronic pain and RSD.3,17,122

These tests include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, the Visual Analogue Scale, and the Dartmouth Pain Questionnaire.17,20,49–51,141 When properly interpreted, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory can provide some useful evaluative information of the personality profiles for some chronic pain states, although some argue its importance as a predictor of treatment success.17,20,41,50,51,87 The McGill Pain Questionnaire is widely used as a method of quantitating subjective pain intensity, and this study, along with other visual quantitation methods, is often useful to assess individual treatment progress.50,51

TREATMENT

After obtaining a thorough historic investigation and physical examination as well as additional objective data from appropriate diagnostic studies, the treating physician should be able to accurately identify those specific components involved in any PDS. All involved components of a PDS must be addressed in the design of a treatment plan if a complete and expeditious recovery from the disorder is to be expected.29,117 Dobyns29 recommends that all components be ordered so that the most predominant problems are listed first. This process results in a prioritized outline from which specific problem-oriented treatment regimens may be begun (see Fig. 81-1). In most cases of PDS, the treatment of certain components is outside the domain of orthopedic surgery, and therefore, consultation of other medical associates to assist in the overall treatment plan is required. Pain control specialists (anesthesiologists), physiatrists, physical therapists, and psychiatrists are most often consulted, owing to their particular expertise in dealing with some of the more common problems involved in recovery from chronic pain and dysfunction.3,29,37 Associates in internal medicine for the treatment of certain systemic disorders, as well as rheumatologists, neurologists, and endocrinologists, may be required in specific instances. By consulting these medical specialists, the primary physician generally yields to their recommendations for specific treatment; however, the patient rightly expects that one physician will remain in overall charge of his or her care. Failure to do so can often result in disastrous failures in treatment stemming from misunderstanding, disillusionment, and distrust.

The treatment of the physical components of a PDS in most cases will come under the direction and care of the orthopedic surgeon, particularly when an injury has occurred. It is obligatory from the outset of treatment to identify any physical and anatomic problems that act as sources of continued pain and dysfunction. Fracture nonunions and malunions, offending internal fixation hardware, postimmobilization joint stiffness, neuromas, painful constrictive scars, and traumatic arthritis are all common examples of continued painful foci that are potentially correctable with surgical intervention. Reluctance on the part of the surgeon to proceed with corrective operative procedures should be dismissed even in cases in which there are recognizable extenuating problems (e.g., previous surgical failures, active psychological dysfunction) because avoidance of recognized treatable problems will ensure perpetuation of the disorder.3

PHYSIOTHERAPY

In addition to the decision for further surgical treatment, the form and direction of a physical therapy program will most often initially come under the direction and control of the orthopedic surgeon. A close association with the therapist should be established early and maintained through completion of rehabilitation. All involved components of a PDS should be discussed with the therapist to delineate the specific physical problems necessitating the referral and to identify any potential impediments to the success of subsequent treatment. Restoration of normal functional activity involves both active and passive modalities, but the design of any physical therapy program for PDS should allow direct patient involvement, along with establishment of clearly defined treatment goals.3,39,125 In the earlier phases of therapy, the degree of pain is usually the determining factor as to which modalities are to be employed. However, active and active-assistive programs are generally most effective because they allow the patient to have some control of his or her level of pain.138 In addition to specific physiotherapy modalities directed toward the site of injury or obvious sources of pain and dysfunction, it is also important to recognize and treat any secondary adaptive physical problems that evolve in adjacent joints and anatomic structures. Examples of a secondary problem would be decreased range of motion of the shoulder and cocontraction of par-ascapular muscles following a prolonged period of immobilization.29

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Pharmacologic pain management may initially be instituted by the musculoskeletal physician. Aside from the need for immediate postoperative narcotic medications, narcotics as a class of drugs in pain management should be avoided in the treatment of a PDS, because drug dependency is often associated with this disorder and identification of such dependency requires early referral for treatment.3,50,108 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and other non-narcotic drugs may be particularly beneficial during the acute phases of the normal dystrophic response and, therefore, may facilitate participation in physical therapy and resumption of normal activities of daily living.3,111 When indicated, anesthetic injections of trigger points and corticosteroid solution injections of joints and about inflamed musculotendinous structures are also effective and easily administered methods to control pain.28,92

Beyond these initial measures in pain management, the consultation of a pain control specialist is recommended for the treatment of refractory functional causes of pain and in all cases in which autonomic dysfunction and sympathetically maintained pain exist. Pain control specialists may use oral, intravenous, and regional nerve blocks as well as adaptive therapeutic measures such as transcutaneous electric stimulation for the control and treatment of chronic functional pain.‡

Sympathetic Blockade

The pharmacologic treatment of the sympathetic nervous system dysfunction of RSD involves blockade of abnormal sympathetic efferent activity by multiple or continuous stellate ganglion blocks; continuous axillary blockade; end organ blockade by intravenous guanethidine, bretylium, or reserpine; and use of systemic calcium channel blockers.§ Pharmacologic treatment alone often is only partially successful in the treatment of sympathetically maintained pain, and an interdisciplinary approach using physical therapy and psychiatry may be initiated by the pain control specialist to successfully treat all the manifestations of the disorder.

THE PSYCHE

The treatment of any recognizable psychic disturbances begins with initiation of any and all measures to resolve the patient’s pain, because as previously mentioned, relief from prolonged pain alone may result in a significant diminishment of any existing psychological and emotional abnormalities.74,75 However, consultation with a psychotherapist should be considered, even for the more situationally induced psychological disturbances described earlier, when such problems are identified as a major feature of a PDS. Depending on the patient, there may be considerable reluctance, denial, and even anger when mention is made of the possibility of any associated psychological factors, and particularly so when a recommendation is made for psychiatric referral. Nothing should be disclosed in a confrontational manner, and prior discussion with the psychotherapist may circumvent any potential negative consequences.3,37

Relaxation therapy, hypnosis, biofeedback, distraction techniques, supportive psychotherapy, and psychotrophic medications have all been shown to be effective in the management of the psychological disturbances associated with chronic pain syndromes.3,29,37,50,82,112,133,134 Likewise, the psychotherapist may assist in resolving familial, economic, and workers’ compensation issues.2,8,12,29,37 Formal psychoanalysis is necessary when somatization disorder, conversion disorder, major depression, malingering, and factitious injury disorders have been identified.37,50,61,62 The early detection and prompt referral to psychotherapists for treatment of these disorders are important to protect the patient from unnecessary surgery, possibly harmful diagnostic tests, the potential for self-inflicted injury, and unnecessary hospitalization and incurred medical costs.3,37,51

CONCLUSION

Pain dysfunction syndrome is unlike most other complications encountered in the treatment of disorders of the upper extremity. The syndrome is a confluence of numerous possible precipitating factors, which may then involve a diversity of physiologic, psychological, and systemic components, yielding an individually variable presentation of pain and extremity dysfunction. Perhaps no other clinical complication is looked on with more consternation, and from this there has historically been an overall reluctance to accept and treat the many problems of this disorder. Dobyns’ approach to PDS solves many of the clinical challenges this syndrome presents by first clarifying the involved components, eliminating nosologic hindrances, and providing guidelines for an effective nonarbitrary treatment program.29 Fortunately, with proper management, all components of a PDS can be alleviated, but treatment always becomes more difficult and protracted the longer the components of the syndrome are allowed to progress before care is initiated. Therefore, the willingness to accept responsibility for treatment remains perhaps the last and most difficult obstacle to overcome.

1 Abram S.E. Incidence-hypotheses-epidemiology. In: Hicks M.S., editor. Pain and the Sympathetic Nervous System. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1989:1.

2 Abram S.E. Causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Curr. Concepts Pain. 1984;2:10.

3 Amadio P.C. Pain dysfunction syndromes: Current concepts review. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:944.

4 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1987:247.

5 Armstrong T.J. Ergonomics and cumulative trauma disorders. Hand Clin. 1986;2:553.

6 Barnes R. The role of sympathectomy in the treatment of causalgia. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35B:172.

7 Betcher A.M., Bean G., Casten D.F. Continuous procaine block or paravertebral sympathetic ganglion: observations in one hundred patients. J. A. M. A. 1953;151:288.

8 Boas R.A.. Complex regional pain syndromes: symptoms, signs, and differential diagnosis. Janig W., Stanton-Hicks M., editors. Reflex Sympathetic Dystophy: A Reappraisal Progress in Pain Research and Management, Vol. 6. Seattle: IASP Press, 1995.

9 Bonelli S., Conoscente F., Movilia P.C., Restelli L., Francucci B., Grossi E. Regional intravenous guanethidine vs. stellate ganglion block in reflex sympathetic dystrophies: A randomized trial. Pain. 1983;16:297.

10 Bonica J.J. Causalgia and other reflex sympathetic dystrophies. Postgrad. Med. 1973;53:143.

11 Bonica J.J.. Causalgia and other reflex sympathetic dystrophies. Bonica J.J., Liebeskind J.C., Albe-Fessard D.G., editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Vol. 3. New York: Raven Press, 1979.

12 Brena S.F., Chapman S.L.. Chronic pain states and compensable disability: An algorithmic approach. Benedetti C., Chapman C.R., Moricca G., editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Vol. 7. Raven Press, New York, 1984;131.

13 Buckle P. Musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities: The use of epidemiologic approaches in industrial settings. J. Hand Surg. 1987;12A:885.

14 Campbell J.N., Raja S.N., Meyer R.A., Mackinnon S.E. Myelinated afferents signal the hyperalgesia associated with nerve injury. Pain. 1988;32:89.

15 Catoggio L.J., Fongi E.G. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy and early damage of carpal bones. Rheumatol. Int. 1985;5:141.

16 Ceserani R., Colombo M., Olgiati V.R., Pecile A. Calcitonin and prostaglandin system. Life Sci. 1979;25:1851.

17 Cox G.B., Chapman C.R., Black R.G. The MMPI and chronic pain: The diagnosis of psychogenic pain. J. Behav. Med. 1978;1:437.

18 Craig K.D. Social modeling influences: Pain in context. In: Sternbach R.A., editor. The Psychology of Pain. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1986:67.

19 Dabis L., Pollock I.J. The role of the sympathetic nervous system in the production of pain in the head. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1932;27:282.

20 Davidoff G., Morey K., Awann M., Starups J. Pain measurement in reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Pain. 1988;32:27.

21 Davies J.A.H., Beswick T., Dickson G. Ketanserin and guanethidine in the treatment of causalgia. Anesth. Analg. 1987;66:575.

22 de Takats G. Reflex dystrophy of the extremities. Arch. Surg. 1937;34:939.

23 de Takats G. Causalgic states in war and peace. J. A. M. A. 1945;128:699.

24 de Takats G. Sympathetic reflex dystrophy. Med. Clin. North Am. 1965;49:117.

25 de Takats G., Miller D.S. Post-traumatic dystrophy of the extremities: A chronic vasodilator mechanism. Arch. Surg. 1943;46:469.

26 Devor M. Nerve pathophysiology and mechanisms of pain in causalgia. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1983;7:371.

27 Devor M. Central changes mediating neuropathic pain. In: Dubner R., Debbhart G.F., Bond M.R., editors. Proceedings of the Vth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988:114.

28 Devor M., Govrin-Lippmann R., Raber P.. Corticosteroids reduce neuroma hyperexcitability. Fields H.L., Dubner R., Cervero P., editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Vol. 9. New York: Raven Press, 1985.

29 Dobyns J.H. Pain dysfunction syndrome vs. reflex sympathetic dystrophy: What’s the difference and does it matter? Am. Soc. Surg. Hand Corresp. Newslett. 1984:92.

30 Drucker W.R., Hubay C.A., Holden W.D., Bukovnic J.A. Pathogenesis of post-traumatic sympathetic dystrophy. Am. J. Surg. 1959;97:454.

31 Duncan K.H., Lewis R.C.Jr., Racz G., Nordyke M.D. Treatment of upper extremity reflex sympathetic dystrophy with joint stiffness using sympatholytic bier blocks and manipulation. Orthopedics. 1988;11:883.

32 Ebersold M.J., Laws E.R., Albers J.W. Measurements of autonomic function before, during and after transcutaneous stimulation in patients with chronic pain and in control subjects. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1977;52:228.

33 Ecker A. Norepinephrine in reflex sympathetic dystrophy: A hypothesis. Clin. J. Pain. 1989;5:313.

34 Eto F., Yoshikawa M., Euda S., Hirai S. Posthemiplegic shoulder-hand syndrome, with special reference to related cerebral localization. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1980;28:13.

35 Fahr L.M., Sauser D.D. Imaging of peripheral nerve lesions. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1988;19:27.

36 Fealey R.D., Low P.A., Thomas J.E. Thermoregulatory sweating abnormalities. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1989;64:617.

37 Fields H.L. Pain Mechanisms and Management. New York: McGraw Hill, 1987;351.

38 Fishbain D.A., Goldberg M., Meagher B.R., Steele R., Rosomoff H. Male and female chronic pain patients categorized by DSM-III psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Pain. 1986;26:181.

39 Fordyce W.F. Behavioral Methods for Chronic Pain and Illness. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby, 1976.

40 Foreman R.D., Blair R.W. Central organization of sympathetic cardiovascular response to pain. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1988;50:607.

41 France R.D., Krishnan K.R.R. Chronic Pain. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, 1988.

42 Gaumer D., Lennon R.L., Wedel D.J. Axillary plexus block-proximal catheter technique for postoperative pain management. Anesthesia. 1987;67:A242.

43 Genant H.K., Kozin F., Bekerman C., McCarty D.J., Sims J. The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Radiology. 1975;117:21.

44 Ghostine S.Y., Comair Y.G., Turner D.M., Kassell N.F., Azar C.G. Phenoxybenzamine in the treatment of causalgia: Report of 40 cases. J. Neurosurg. 1984;60:1263.

45 Gibbons J.J., Wilson P.R., Lamer T.S., Gibson B.E. Interscalene blocks for chronic upper extremity pain. Reg. Anaesth. 1988;13:50.

46 Glynn C.J., White S., Evans K.H.A. Reversal of the osteoporosis of sympathetic dystrophy following sympathetic blockade. Anaesth. Intens. Care. 1982;10:362.

47 Goldenberg D.L. Fibromyalgia syndrome: An emerging but controversial condition. J. A. M. A. 1987;257:2782.

48 Goldner J.L., Urbaniak J.R., Bright D.S., Seaber A.V., Hendrix P.C., Davenport C. Sympathetic dystrophy, upper extremity: Prediction, prevention, and treatment (abstr.). J. Hand Surg.. 1980;5:289.

49 Grunert, B. K., Devine, C. A., Sanger, J. R., Matloub, M. S., and Green, D.: Thermal self-regulation for pain control in reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Presented at the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the American Association for Hand Surgery, Toronto, 1988.

50 Haddox J.D. Psychological aspects of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In: Hicks M.S., editor. Pain and the sympathetic nervous system. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1989:107.

51 Haddox J.D., Abram S.E., Hopwood M.H. Comparison of psychometric data in RSD and radioculopathy. Reg. Anaesth. 1988;13:27.

52 Hadler N.M. Illness in the workplace: The challenge of musculoskeletal symptoms. J. Hand Surg. 1985;10A:451.

53 Hammond D.L. Control systems for nociceptive afferent processing: The descending inhibitory pathways. In: Yaksh T.L., editor. Spinal Afferent Processing. New York: Plenum Press; 1986:363.

54 Hannington-Kiff J.G. Pharmacological target blocks in hand surgery and rehabilitation. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9B:29.

55 Hannington-Kiff J.G. Relief of Sudeck’s atrophy by regional intravenous guanethidine. Lancet. 1977;1:1132.

56 Herrmann L.G., Reineke H.G., Caldwell J.A. Post-traumatic painful osteoporosis: A clinical and roentgenological entity. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1942;47:353.

57 Hobelmann C.F.Jr., Dellon A.L. Use of prolonged sympathetic blockade as an adjunct to surgery in the patient with sympathetic maintained pain. Microsurgery. 1989;10:151.

58 Holden W.D. Sympathetic dystrophy. Arch. Surg. 1948;57:373.

59 IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy: Pain terms: A list with definitions and notes on usage. Pain. 1979;6:249.

60 Johansson F., Almay B.G.L., Von Knorring L., Terenius L. Predictors for the outcome of treatment with high frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 1980;9:55.

61 Katon W., Kleinman A., Rosen G. Depression and somatization. A review: I. Am. J. Med. 1982;72:127.

62 Katon W., Kleinman A., Rosen G. Depression and somatization. A review: II. Am. J. Med. 1982;72:241.

63 Kehlet H. Modification of responses to surgery by neural blockade: Clinical implications. In: Cousins M.J., Bridenbaugh P.O., editors. Neural Blockade in Clinical Anaesthesia and Management of Pain. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.; 1988:145.

64 Koman L.A. Current status of noninvasive techniques of the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the upper extremity. Instruct. Course Lect. 1983;32:61.

65 Koman L.A., Nunley J.A., Goldner J.L., Seaber A.V., Urbaniak J.R. Isolated cold stress testing in the assessment of symptoms in the upper extremity: Preliminary communication. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9A:303.

66 Koman L.A., Nunley J.A., Wilkins R.H.Jr., Urbaniak J.R., Coleman R.E. Dynamic radionuclide imaging as a means of evaluating vascular perfusion of the upper extremity: A preliminary report. J. Hand Surg. 1983;8:424.

67 Kozin F. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. Bull. Rheum. Dis. 1986;36:1.

68 Kozin F., Genant H.K., Bekerman C., McCarty D.J. The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome: II. Roentgenographic and scintigraphic evidence of bilaterality and of periarticular accentuation. Am. J. Med. 1976;60:372.

69 Kozin F., McCarty D.J., Sims J., Genant H. The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome: I. Clinical and histological studies: Evidence for bilaterality, response to corticosteroids and articular involvement. Am. J. Med. 1976;60:321.

70 Kozin F., Ryan L.M., Carerra G.F., Soin J.S. The reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (RSDS): III. Scintigraphic studies, further evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of systemic corticosteroids, and the proposed diagnostic criteria. Am. J. Med. 1981;70:23.

71 Lankford L.L. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the upper extremity. In Flynn J.E., editor: Hand Surgery, 3rd ed., Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1982.

72 Lankford L.L. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In: Hunter J.M., editor. Rehabilitation of the Hand. 2nd ed. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby; 1984:509-532.

73 Lankford L.L. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. In: Green D.P., editor. Operative Hand Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988:637.

74 Lankford L.L., Thompson J.E. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, upper and lower extremity: Diagnosis and management. Instruct. Course Lect. 1977;26:163.

75 Lee M.H., Ernst M. The sympatholytic effect of acupuncture as evidenced by thermography: A preliminary report. Orthop. Rev. 1983;12:67.

76 Linson M.A., Leffert R., Todd D.P. The treatment of upper extremity reflex sympathetic dystrophy with prolonged continuous stellate ganglion blockade. J. Hand Surg. 1983;8:153.

77 Livingston W.K. Pain Mechanism: A Physiological Interpretation of Causalgia and Its Related States. New York: Macmillan, 1943.

78 Loh L., Nathan P.W. Painful peripheral states and sympathetic blocks. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1978;41:664.

79 Loh L., Nathan P.W., Schott G.D., Wilson P.G. Effects of regional guanethidine infusion in certain painful states. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1980;43:446.

80 Long D.M. Electrical stimulation for relief of pain from chronic nerve injury. J. Neurosurg. 1973;39:718.

81 Lorente de No R. Analysis of the activity of the chains of internuncial neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1938;1:207.

82 Louis D.S., Lamp M.K., Greene T.L. The upper extremity and psychiatric illness. J. Hand Surg. 1985;10A:687.

83 Low P.A., Caskey P.E., Tuck R.R., Fealey R.D., Dyck P.J. Quantitative sudometer axon test in normal and neuropathic subjects. Ann. Neurol. 1983;14:573.

84 MacKinnon S.E., Dellon A.L. Surgery of the Peripheral Nerve. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 1988;492-504.

85 MacKinnon S.E., Holder L.E. The use of three-phase radionuclide bone scanning in the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9:556.

86 Magee C.P., Grosz H.J. Propranolol for causalgia (letter). J. A. M. A. 1974;228:826.

87 Maruta T., Swanson D.W., Swenson W.M. Chronic pain: Which patients may a pain management program help? Pain. 1979;7:321.

88 Mayfield F.H., Devine J.W. Causalgia. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1945;80:631.

89 McCain G.A., Scudds R.A. The concept of primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): Clinical value, relation and significance to other chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes. Pain. 1988;37:273.

90 McKain C.W., Urban B.J., Goldner J.L. The effects of intravenous regional guanethidine and reserpine. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A:808.

91 Melzack R. Prolonged relief of pain by brief, intense transcutaneous somatic stimulation. Pain. 1975;1:357.

92 Melzack R., Stillwell D.M., Fox E.J. Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: Correlations and implications. Pain. 1977;3:3.

93 Melzack R., Wall P.D. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971.

94 Mershey H., Bogdeuk N. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prog. Pain Res. Manage. 1994;1:39.

95 Miller D.S., de Takats G. Post-traumatic dystrophy of the extremities: Sudeck’s atrophy. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1942;75:558.

96 Mitchell S.W. Injuries of Nerves and Their Consequences. London: Smith Elder, 1872.

97 Mockus M.B., Rutherford R.B., Rosales C., Pearce W.H. Sympathectomy for causalgia: Patient selection and long-term results. Arch. Surg. 1987;122:668.

98 Nashold B.S.Jr., Goldner J.L., Mullen J.B., Bright D.S. Long-term pain control by direct peripheral-nerve stimulation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:1.

99 Omer G. Management of pain syndromes in the upper extremity. In: Hunter J.M., Schneider L.H., Macklin E.J., Bell J.A., editors. Rehabilitation of the Hand. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby, 1978.

100 Omer G., Thomas S. Treatment of causalgia: review of cases at Brooke General Hospital. Tex. Med. 1971;67:93.

101 Oschoa J.L., Yainitsky D., Marchettini P., Dotso R., Dotson R., Cline M. Interactions between sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow and C noceceptor-induced antidromic vasodilatation. Pain. 1993;54:191.

102 Owitz S., Koppolu S. Sympathetic blockade as a diagnostic and therapeutic technique. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 1982;49:282.

103 Pak T.J., Martin G.M., Magness J.L., Kavanaugh G.J. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: Review of 140 cases. Minn. Med. 1970;53:507.

104 Payne R. Neuropathic Pain Syndromes, With Special Reference to Causalgia and Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. New York: Raven Press, 1986.

105 Perelman R.B., Adler D., Humphreys M. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: Electronic thermography as an aid in diagnosis. Orthop. Rev. 1987;16:561.

106 Pochaczevsky R., Wexler C.E., Meyers P.H., Epstein J.A., Marc J.A. Liquid crystal thermography of the spine and extremities: Its value in the diagnosis of spinal root syndromes. J. Neurosurg. 1982;56:386.

107 Pollock F.E.Jr., Koman L.A., Toby E.B., Barden A., Poehling G.C. Thermoregulatory patterns associated with reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the hand and wrist. Orthop. Trans. 1990;14:156.

108 Portenoy R.K., Foley K.M. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: Report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171.

109 Procacci P., Maresca M. Reflex sympathetic dystrophies and algodystrophies: Historical and pathogenic considerations. Pain. 1987;31:137.

110 Prough D.S., McLeskey C.H., Poehling G.G., Koman L.A., Weeks D.B., Whitworth T., Semble E.L. Efficacy of oral nifedipine in the treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:796.

111 Raja S.N., Meyer R.A., Campbell J.N. Peripheral mechanisms of somatic pain. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:571.

112 Reuler J.B., Girard D.E., Nardone D.A. The chronic pain syndrome: Misconceptions and management. Ann. Intern. Med. 1980;93:588.

113 Rizzi R., Visentin M., Mazzetti G.. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Benedetti C., Chapman C.R., Moricca G., editors. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Vol. 7. New York: Raven Press, 1984.

114 Roberts W.J. A hypothesis on the physiological basis for causalgia and related pains. Pain. 1986;24:297.

115 Rowlingson J.C. The sympathetic dystrophies. In: Stem J.M., Wakefield C.A., editors. Pain Management. Boston: Little, Brown; 1983:117.

116 Schott G.D. Mechanisms of causalgia and related clinical conditions: The role of the central and of the sympathetic nervous system. Brain. 1986;109:717.

117 Schutzer S.F., Gossling H.R. The treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:625.

118 Schwartzman R.J., McLellan T.L. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, a review. Arch. Neurol. 1987;44:555.

119 Sherman R.A., Barja R.H., Bruno G.M. Thermographic correlates of chronic pain: Analysis of 125 patients incorporating evaluations by a blind panel. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 1987;68:273.

120 Shumacker H.B.Jr. A personal overview of causalgia and other reflex dystrophies. Ann. Surg. 1985;201:278.

121 Smith R.J., Monson R.A., Ray D.C. Patients with multiple unexplained symptoms: Their characteristics, functional health, and health care utilization. Arch. Intern. Med. 1986;146:69.

122 Southwick S.M., White A.A. Current concepts review: The use of psychological tests in the evaluation of low-back pain. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A:560.

123 Spebar M.J., Rosenthal D., Collins G.J., Jarstfer B.S., Walters M.J. Changing trends in causalgia. Am. J. Surg. 1981;142:744.

124 Speigel I.J., Milowsky J.L. Causalgia. J. A. M. A. 1945;127:9.

125 Spero M.W., Schwartz E. Psychiatric aspects of foot problems. In: Jahss M.H., editor. Disorders of the Foot. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1982.

126 Spiegel D., Chase R.A. The treatment of contractures of the hand using self-hypnosis. J. Hand Surg. [Am]. 1980;5:428.

127 Spurling R.G. Causalgia of the upper extremity: Treatment by dorsal sympathetic ganglionectomy. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1930;23:784.

128 Steinbrocker O. The shoulder-hand syndrome: Present status as a diagnostic and therapeutic entity. Med. Clin. North Am. 1958;42:1537.

129 Sternbach R.A., Timmermans G. Personality changes associated with the reduction of pain. Pain. 1975;1:1771.

130 Sunderland S. The painful sequelae of injuries to peripheral nerves. In: Sunderland S., editor. Nerves and Nerve Injuries. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1978:377.

131 Sunderland S. Pain mechanisms in causalgia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1976;39:471.

132 Tabira T., Shibasaki H., Kuroiwa Y. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy (causalgia) treatment with guanethidine. Arch. Neurol. 1983;40:430.

133 Thompson R.L.II. Chronic pain. In: Kaplan H.I., Sadock B.J., editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.

134 Turner J.A., Chapman C.R. Psychological interventions for chronic pain: A critical review. II. Operant conditioning, hypnosis and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Pain. 1982;12:23.

135 Uematsu S., Hendler N., Hungerford D., Long D., Ono N. Thermography and electromyography in the differential diagnosis of chronic pain syndromes and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1981;21:165.

136 Wall P.D. Stability and instability of central pain mechanisms. In: Dubner R., Gebhart G.F., Bond M.R., editors. Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988:13.

137 Wang J.K., Erickson R.P., Ilstrup D.M. Repeated stellate ganglion blocks for upper extremity reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Reg. Anaesth. 1985;10:125.

138 Watson H.K., Carlson L., Brenner L.H. The “dystrophile” treatment of reflex dystrophy of the hand with an active stress loading program. Orthop. Trans. 1986;10:188.

139 White J.C., Sweet W.H. Pain and the Neurosurgeon. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1969.

140 Willis W.D.Jr. Ascending somatosensory systems. In: Yaksh T.L., editor. Spinal afferent processing. New York: Plenum Press; 1986:243.

141 Wilson P.R. Sympathetically maintained pain: Diagnosis, measurement, and efficacy of treatment. In: Hicks M.S., editor. Pain and the Sympathetic Nervous System. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1982:91.

142 Wilson R.L. Management of pain following peripheral nerve injuries. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1981;12:343.

143 Wirth F.P., Rutherford R.B. A civilian experience with causalgia. Arch. Surg. 1970;100:637.

144 Withrington R.M., Wynn-Parry C.B. The management of painful peripheral nerve disorders. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9B:24.

145 Withrington R.M., Wynn-Parry C.B. Rehabilitation of conversion paralysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67B:635.

146 Woodyard J.E. Diagnosis and prognosis in compensation claims. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1984;64:191.

* See references 1, 22–25, 71, 73, 74, 77, 96, 99, 123, 141, and 143.

* See references 11, 25, 29, 58, 71–74, 88, 96, 99, 103, 106, and 121.

‡ See references 3, 7, 28, 31, 32, 42, 45, 60, 80, 86, 98, 100, 113, and 132.

§ References 6, 9, 16, 21, 42, 44, 55, 57, 76, 79, 86, 88, 90, 110, 111, 127, 131, and 137.