Chapter 103 Paediatric trauma

The management of paediatric trauma is different from adults. Paediatric patients presenting with trauma have mechanisms of injury, clinical symptoms and examination findings which differ from adults, and differ across the range of their ages. Trauma is by far the leading cause of death in children over 1 year old, and the third leading cause less than 1 year after congenital abnormalities and sudden infant death syndrome.1 Causes of trauma and patterns of injury are determined by age-related behaviour, with falls and assaults more common in younger children, and motor vehicle accidents more common in older children. Injury patterns differ, with impact forces dissipated over a smaller target, severe organ damage resulting without bony fracture because bones are not ossified, and greater potential for hypothermia. In general, blunt trauma with multiorgan injury is most likely.

As with adults, there are three peak mortality periods after injury:

The mainstay of early management is optimising the ABC of resuscitation as outlined in other chapters. Importantly, vascular access can be difficult, and expertise in intraosseous needle insertion is essential.2

PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Paediatric trauma requires resources and separate systems to successfully reduce mortality and morbidity.3 New emphasis has seen the development of prevention strategies (Table 103.1), including:

| Paediatric injuries | Preventative strategies |

|---|---|

| MVA – occupant | Child car seat |

| Seatbelt restraints | |

| Car design | |

| Airbags | |

| MVA – pedestrian | Safety programmes in schools |

| Bicycle | Helmet |

| Separate sidewalks | |

| Playground | Equipment structural design |

| Soft surfaces | |

| Drowning | Surround pool fencing |

| Burns | Smoke detectors |

| Water tap regulators | |

| Flammable fabric legislation | |

| Poisoning | Preventative packaging |

| Violence | Hand gun legislation |

| Crisis resolution counselling |

HEAD INJURY

Significant head injury occurs in 75% of children admitted with blunt trauma,5 and 70% of these result in death. Causes of injury are determined by behaviour patterns, which change with age and are commonly due to falls and assaults in infants, and motor vehicle accidents (including bicycle-related injuries) in older children.

ASSESSMENT

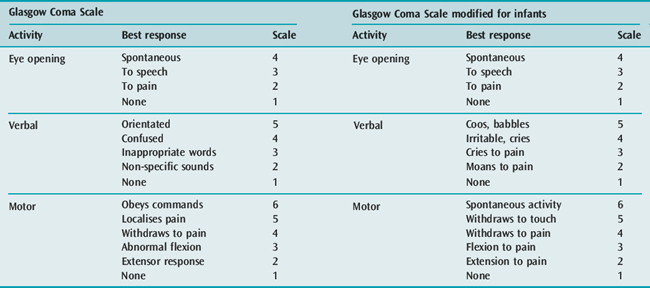

This has led to attempts to modify the scale by either changing the scoring assessment signs, or by reducing the total score (i.e. eliminating some response categories).6 The latter does not allow for comparison of outcome data.

An example of a commonly used scale modified for infants is shown in Table 103.2. However, difficulties remain as regards the accuracy and reproducibility of GCS for infants. Clinical assessment must prioritise the signs and symptoms of cerebral oedema or raised intracranial pressure (ICP) (Table 103.3).

MANAGEMENT

DIAGNOSTIC INVESTIGATIONS

A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan in stable patients excludes surgically treatable lesions, assesses the size of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces, including the basal cisterns, detects herniation and shift, and shows the presence of hyperaemia, oedema, intracerebral haematomas, contusions and fractures. A normal CT scan does not exclude raised ICP. Intracranial blood collections are less common than in adults.5 The following are poor prognostic signs:

CEREBRAL PERFUSION PRESSURE

Normal ICP is also lower,15 being normally less than 5 mmHg (0.67 kPa) at 2 years and less than 10 mmHg (1.3 kPa) at 5 years. Thus, in younger age groups, relative hypotension has a more profound effect on CPP and outcome,16 and hypotension may be the main cause of cerebral ischaemia. For adolescents, therapy should aim to sustain CPP at 60–70 mmHg (8.0–9.3 kPa), while maintaining normal blood volume and adequate blood pressure (with pressor agents if required). A CPP less than 40 mmHg (5.3 kPa) reduces the likelihood of intact survival. Younger patients should have therapeutic targets adjusted to age-related realistic end-points.

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Mechanisms of raised ICP in childhood trauma are listed in Table 103.4. If ICP remains persistently raised and uncompensated, cerebral ischaemia and herniation result. This herniation can be cingulate, uncal (temporal lobe), cerebellar tonsillar, upward cerebellar (posterior fossa hypertension) or transcalvarian (through vault defects). Signs of herniation are as for raised ICP (Table 103.3).

REDUCTION OF RAISED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

Several mechanisms allow physiological compensation for raised ICP in children (Table 103.5). In the child under 18 months of age, a gradual increase in intracranial volume is achieved by an increase in head circumference. Measurement of the circumference is important, because compensation can delay recognition of clinical signs and diagnosis in emerging intracranial pathology. The important factor in the rate of change in compliance and ICP is the elasticity of the dura, which is dependent on the rate of change in intracranial volume.

Table 103.5 Physiological compensatory mechanisms for raised intracranial pressure in children

Hyperventilation is effective in lowering raised ICP. However, excessive hyperventilation may cause cerebral ischaemia, and PaCO2 should be maintained between 35 and 40 mmHg (4.7–5.3 kPa). Weaning from hyperventilation should be slow, to minimise rebound rises in ICP.19 Fluid restriction is helpful, provided circulating blood volume is maintained.

Furosemide (1 mg/kg) reduces cerebral water and CSF production, but excessive diuresis from mannitol or furosemide may compromise the circulation. The use of hypertonic saline in children (3%) reduces ICP and appears to be more beneficial in resuscitation. CSF drainage is possible if a ventricular drain is in situ. Controlled hypothermia reduces raised ICP in patients with refractory intracranial hypertension, but improvement in outcomes is uncertain. Surgical decompression or removal of cerebral contusion in the face of intractably raised ICP in head trauma is advocated,5 with improved results in unremitting focal oedema.

SPINAL CORD INJURY

Spinal cord injury is rare in children. Anatomical differences in children under 8 years render their spines more mobile and subject to stress with flexible ligaments and joint capsules, less muscular support, and horizontal facet joints. In addition, the relatively large head mass increases momentum, with the fulcrum of mobility at C2–C3 as opposed to C4–C5 in the adult. Thus paediatric cervical spine injuries tend to be above C4. The use of seat belts has led to an increase in lumbar spinal cord injury in children.20

ASSESSMENT

Clinical assessment can be difficult, as can the interpretation of radiological investigations because of normal variation and age-dependent ossification changes. Spinal cord injury without obvious radiological abnormality (SCIWORA) occurs in 10–20% of all paediatric spinal cord injuries.21 Sensory-evoked potentials can be a valuable adjunct to diagnosis. Spinal cord injury can only be dismissed after imaging assessments (which may include magnetic resonance imaging in the non-acute setting) and careful and repeated examination of the lucid patient.

MANAGEMENT

It is often difficult to decide whether the spinal-injured child is initially best cared for in a paediatric ICU or a specialised spinal unit. This decision will be ultimately determined on the age of the child and the stability of the spine. Certainly, infants should not be managed in adult spinal units, whereas for older children, expertise in spinal care may be more important. However, once spinal column stability and surgical fixation have been achieved, children are best managed in paediatric facilities for ongoing management and rehabilitation.22 Ongoing care is complex, and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Attention to pressure areas, bladder and bowel care and training, nutrition and prevention of contractures is essential. Symptoms of hypercalcaemia (e.g. vomiting, anorexia, nausea and malaise) can be distressing and difficult to control. Depression is common in adolescents. With high spinal cord injury, chin-operated battery-powered wheelchairs, portable ventilators and computer-activated environment control devices allow for relative independence and a functional lifestyle.

THORACIC TRAUMA

Despite a low incidence in children, thoracic trauma is usually associated with multiorgan injury and high mortality.23 The mechanism of injury is almost entirely related to motor vehicle accidents, with penetrating trauma being uncommon. The child’s small size and more elastic chest wall allow transmission of more kinetic energy to intrathoracic structures, with a high incidence of pulmonary contusions without rib fractures or flail chest.

As for adults, life-threatening injuries which require immediate intervention are upper-airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, flail chest, pericardial tamponade and massive haemothorax (see Chapter 69). Potentially life-threatening injuries are airway rupture, pulmonary contusion, ruptured aorta, diaphragmatic rupture, oesophageal perforation and myocardial contusion. Contrast CT scan and angiography are the methods of choice in diagnosing aortic rupture in children.

ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

Abdominal trauma is usually associated with blunt injury24 and recognition maybe difficult in the presence of multisystem injury. Mortality is relatively high and missed abdominal trauma is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality.25 The abdominal wall and thoracic cage of children provide less protection to intra-abdominal organs. Also, the liver and spleen are relatively large and more exposed below the rib cage. Forces need not be excessive to cause rupture of internal organs. Absence of bruising does not exclude injury while bruising means severe injury is likely. Lap seat belt injuries are an important cause of abdominal injury in restrained children.

Improvements in radiological imaging techniques have allowed blunt abdominal trauma to be managed conservatively in children.26 This approach requires appropriate monitoring and supervision in a paediatric intensive care setting, with an awareness of the need for urgent intervention, i.e. laparotomy (Table 103.6).

Table 103.6 Indications for laparotomy in paediatric abdominal trauma28

NON-ACCIDENTAL INJURY

With regard to the history, suspicion should be raised when:

Physical examination should be thorough, to establish a pattern of injury.29 Multiple bruises in differing stages of development can be separately estimated for age. Patterns for burns are typical for forced immersion in hot water (with sparing of the groin area) and from cigarettes. Suspicion should be raised where cerebral trauma is associated with retinal haemorrhages, subdural haematomas or fractures. Findings of retinal haemorrhages on ophthalmological examination increases suspicion for inflicted injury but do not confirm the diagnosis.30 The most common intracranial pathology is subdural and subarachnoid haemorrhage, which account for the higher morbidity and mortality. A whole-body X-ray series and bone scan will detect fractures in differing stages of healing from multiple assaults.

TRANSPORT

The outcome of trauma in remote locations is optimal when advice, prehospital stabilisation and transport are provided by teams based in tertiary paediatric ICUs.31 Secondary insults occur more frequently when paediatric-trained personnel are not used for transport.32 A referral and retrieval infrastructure which links a tertiary centre to outlying areas within the region is necessary. Local health care providers must have sufficient skills to stabilise any critically ill child adequately. The transport team must offer a level of care during the stabilisation and transport phases that is equivalent to that of the receiving paediatric ICU.

BRAIN DEATH

Determination of brain death in children has different implications.33 Isoelectric EEGs have been reported in neonates with partially preserved clinical brain function, and cerebral death can occur without marked increase in ICP, allowing partial cerebral blood flow in the presence of brain death criteria and electrocerebral silence. In addition, partial brain recovery has been demonstrated after prolonged periods of clinical unresponsiveness. So for determination of brain death, consideration needs to be given to longer observation periods, more frequent use of confirmatory tests, and an emphasis on the history and clinical findings.

The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society recommendations on brain death and organ donation only make reference to the under 2 months age group when ‘determination of brain death may be more difficult and different time periods may be required’.34 Importantly, there is a lack of evidence for any required observation periods, so that cerebral blood flow imaging may be required in the neonate and infant. The most important factors when determining brain death are in knowing the cause of coma, and being certain of its irreversibility. Time must be allowed for relatives to come to terms with the diagnosis, and there is a responsibility to discuss organ donation. Having relatives watch the physical examination for brain death testing is helpful.

ORGAN DONATION

Parents and relatives have to deal with:

Success in asking for paediatric organs from parents is associated with:

Factors inhibiting a willingness to donate by parents include:

WITHDRAWAL OF SUPPORT

The emotion surrounding a child’s impending death can be overwhelming for both relatives and intensive care staff. Children are involved in sudden and catastrophic events that at times seem unreasonable and unfair. For parents, the grieving process begins before or during the intensive care admission, and intensive care staff are intimately involved in helping parents and relatives through this process. The death of any child is a tragedy, and communication between staff is important to ensure appropriate emotional support. Intensive care staff need to understand that withdrawal of therapy can be appropriate. Ensuring the process has dignity and helping relatives through their grieving process are important facets of the intensive care commitment.35

1 Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozana R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:523-526.

2 Smith R, Davis N, Bouamra O, et al. The utilisation of intraosseous infusion in the resuscitation of paediatric major trauma patients. Injury. 2005;36:1034-1038.

3 Potoka DA, Schall LC, Gardner M, et al. Impact of pediatric trauma centres on mortality in a statewide system. J Trauma. 2000;49:237-245.

4 Maconochie I. Accident prevention. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:275-277.

5 Lam WH, Mackersie A. Paediatric head injury: incidence, aetiology and management. Paediatr Anaesth. 1999;9:377-385.

6 Simpson D, Reilly P. Paediatric coma scale. Lancet. 1982;2:450.

7 Kokoska ER, Smith GS, Pittman T. Early hypotension worsens neurological outcome in pediatric patients with moderately severe head trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:333-338.

8 Michaud LJ, Rivara FP, Longstreth WT, et al. Elevated initial blood glucose levels and poor outcome following severe brain injuries in children. J Trauma. 1991;31:1362-1366.

9 Ross AK. Pediatric trauma. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2001;19:309-337.

10 Feldman Z, Kanter MJ, Robertson CS, et al. Effect of head elevation on intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, and cerebral blood flow in head-injured patients. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:207-211.

11 Hahn YS, Chyung C, Barthel MJ, et al. Head injuries in children under 36 months of age. Demography and outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988;4:34-40.

12 Temkin NR, Dikmen SS, Winn HR. Management of head injury. Posttraumatic seizures. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:425-435.

13 Dearden NM, Midgley S. Technical considerations in continuous jugular venous oxygen saturation measurement. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1993;59:91-97.

14 Horan MJ. Report of the second task force on blood pressure in children. Pediatrics. 1987;79:1-25.

15 Welch K. The intracranial pressure in infants. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:693-699.

16 Raju TN, Vidyasagar D, Papazafiratou C. Cerebral perfusion pressure and abnormal intracranial waveforms: their relation to outcome in birth asphyxia. Crit Care Med. 1981;9:449-453.

17 Bruce DA, Alavi A, Bilaniuk L, et al. Diffuse cerebral swelling following head injuries in children: the syndrome of ’malignant brain edema’. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:170-178.

18 Snoek JW, Minderhoud JM, Wilmink JT. Delayed deterioration following mild head injury in children. Brain. 1984;107:15-36.

19 Havill JH. Prolonged hyperventilation and intracranial pressure. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:72-74.

20 Newman KD, Bowman LM, Eichelberger MR. The lap belt complex: intestinal lumbar spin injury in children. J Trauma. 1990;30:1140-1144.

21 Slack SE, Clancy MJ. Clearing the cervical spine of paediatric trauma patients. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:189-193.

22 Sherwin ED, O’Shanick GJ. The trauma of paediatric and adolescent brain injury: issues and implications for rehabilitation specialists. Brain Inj. 2000;3:267-284.

23 Peclet MH, Newman KD, Eichelberer MR, et al. Thoracic trauma in children: an indicator of increased mortality. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:961-966.

24 Cooper A, Barlow B, DiScala C, et al. Mortality and truncal injury: the pediatric perspective. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:33-38.

25 Holmes JF, Sokolove PE, Brant WE, et al. Identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;5:500-509.

26 Erin S, Shandling B, Simpson J, et al. Nonoperative management of traumatised spleen in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1978;13:117-119.

27 Akgur FM, Aktug T, Olguner M, et al. Prospective study investigating routine use of ultrasonography as the initial diagnostic modality for the evaluation of children sustaining blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:626-628.

28 Rance CH, Singh SJ, Kimble R. Blunt abdominal trauma in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:2-6.

29 Vandeven AM, Newton AW. Update on child physical abuse, sexual abuse, and prevention. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:201-205.

30 Bechtel K, Stoessel K, Leventhal JM, et al. Characteristics that distinguish accidental from abusive injury in hospitalised young children with head trauma. Pediatrics. 2004;114:165-168.

31 Pearson G, Shann F, Barry P, et al. Should paediatric intensive care be centralised? Trent versus Victoria. Lancet. 1997;349:1213-1217.

32 McNab JM. Optimal escort for interhospital transport of pediatric emergencies. J Trauma. 1991;31:205-209.

33 Fishman MA. Validity of brain death criteria in infants. Pediatrics. 1995;96:513-515.

34 Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society. Recommendations Concerning Brain Death and Organ Donation, 2nd edn. Melbourne: ANZICS, 1998.

35 Matthews NT. Issues of withdrawal of therapy and brain death in paediatric intensive care. Crit Care Resusc. 1999;1:7-12.