Paediatric emergencies

The seriously ill child

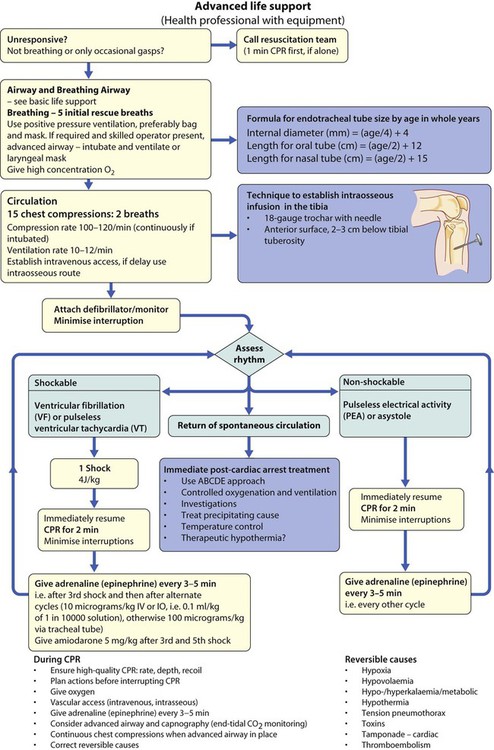

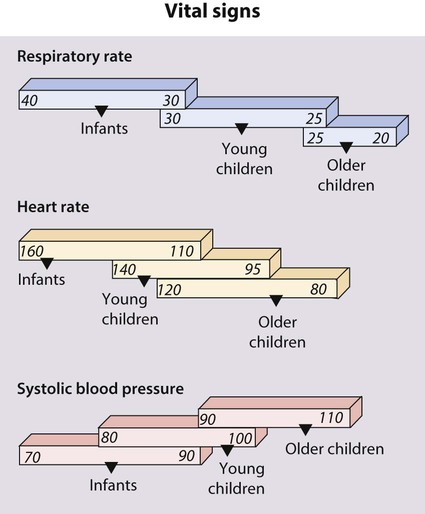

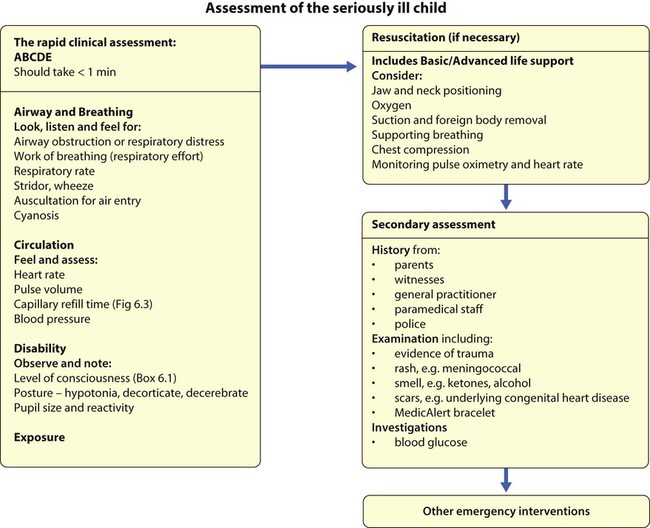

The rapid clinical assessment of the seriously ill child will identify if there is potential respiratory, circulatory or neurological failure. This should take less than 1 minute. Normal vital signs are shown in Figure 6.1 and how a rapid assessment is performed is shown in Figure 6.2.

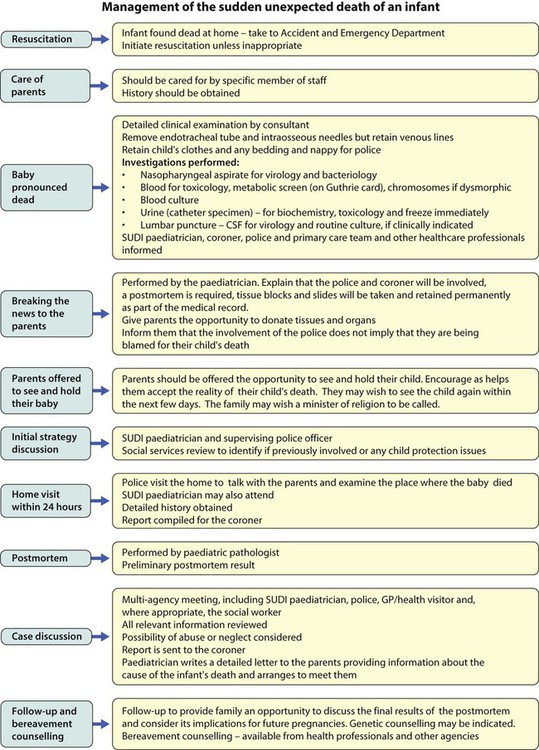

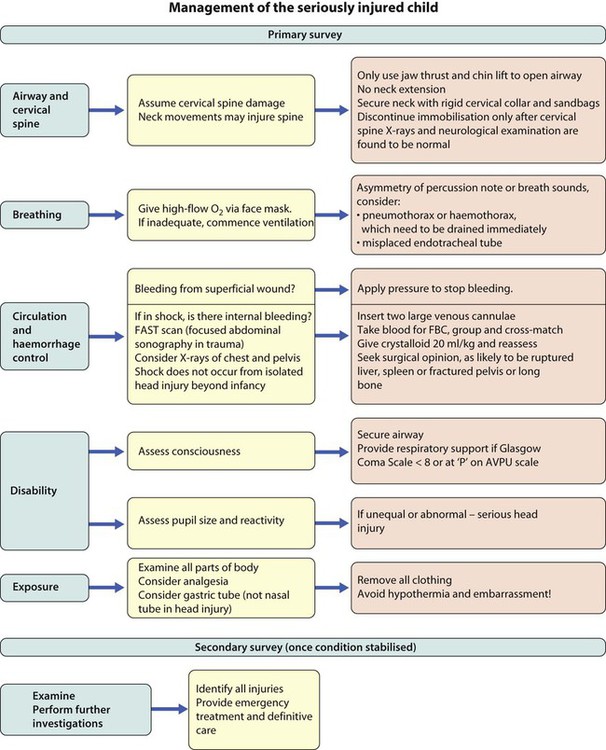

The seriously ill child may present with shock, respiratory distress, as a drowsy/unconscious or fitting child or with a surgical emergency. Their causes are listed in Figure 6.4. In children, the key to successful outcome is the early recognition and active management of conditions that are life-threatening and potentially reversible.

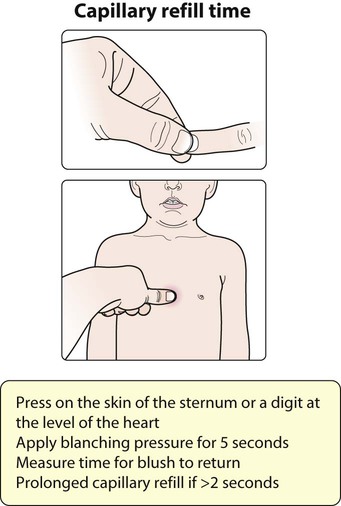

![]() Capillary refill time is affected by body exposure to a cold environment.

Capillary refill time is affected by body exposure to a cold environment.

Shock

Why are children so susceptible to fluid loss?

Children normally require a much higher fluid intake per kilogram of body weight than adults (Table 6.1). This is because they have a higher surface area to volume ratio and a higher basal metabolic rate. Children may therefore become dehydrated if:

Table 6.1

Fluid intake at different ages

| Body weight | Fluid requirement/24 h | Volume/kg per hour (approximate) |

| First 10 kg | 100 ml/kg | 4 ml/kg |

| Second 10 kg | 50 ml/kg | 2 ml/kg |

| Subsequent kg | 20 ml/kg | 1 ml/kg |

| Examples of calculations | ||

| Infant (7 kg) | 700 ml | 28 ml/h |

| Child (18 kg) | 1000 + 400 = 1400 ml | 40 + 16 = 56 ml/h |

| Adolescent (42 kg) | 1000 + 500 + 440 = 1940 ml | 40 + 20 + 22 = 82 ml/h |

• they are unable to take oral fluids

• there are additional fluid losses due to fever, diarrhoea or increased insensible losses (e.g. due to increased sweating or tachypnoea)

• there is loss of the normal fluid-retaining mechanisms, e.g. burns, the permeable skin of premature infants, increased urinary losses or capillary leak.

Clinical features

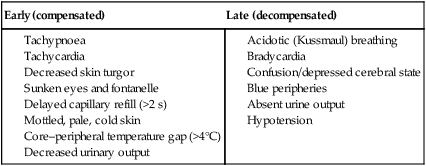

The clinical features of shock are manifestations of compensatory physiological mechanisms to maintain the circulation and the direct effects of poor perfusion of tissues and organs (Box 6.2).

In early, compensated shock, the blood pressure is maintained by increased heart and respiratory rate, redistribution of blood from venous reserve volume and diversion of blood flow from non-essential tissues such as the skin in the peripheries, which become cold, to the vital organs like brain and heart. In shock due to dehydration, there is usually >10% loss of body weight (see Ch. 13) and a profound metabolic acidosis which is compounded by failure to feed and drink while severely ill. After acute blood loss or redistribution of blood volume because of infection, low blood pressure is a late feature. It signifies that compensatory responses are failing.

Management priorities

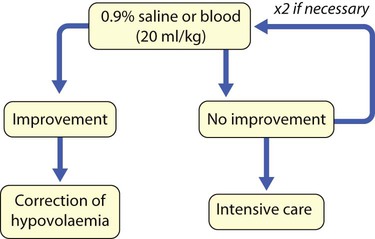

Fluid resuscitation

Rapid restoration of the intravascular circulating volume is the priority (Fig. 6.8). This will usually be with 0.9% saline, or blood if following trauma.

Coma

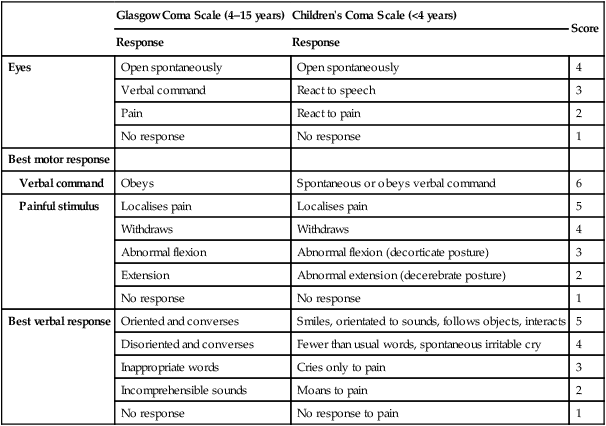

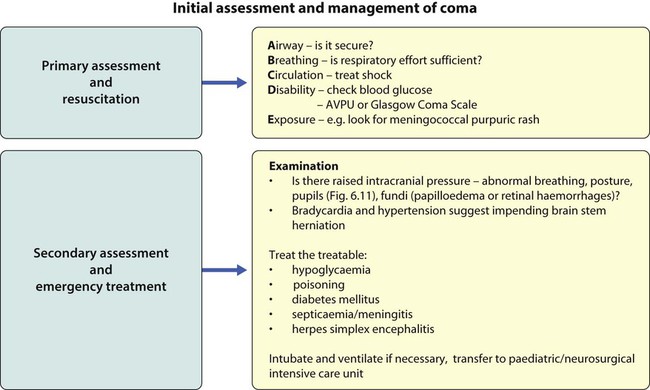

In coma, there is disturbance of the functioning of the cerebral hemispheres and/or the reticular activating system of the brainstem. The level of awareness may range from excessive drowsiness to unconsciousness. It is assessed rapidly by using AVPU (Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive) or the Glasgow Coma Scale (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

Glasgow Coma Scale, incorporating Children’s Coma Scale

| Glasgow Coma Scale (4–15 years) | Children’s Coma Scale (<4 years) | Score | |

| Response | Response | ||

| Eyes | Open spontaneously | Open spontaneously | 4 |

| Verbal command | React to speech | 3 | |

| Pain | React to pain | 2 | |

| No response | No response | 1 | |

| Best motor response | |||

| Verbal command | Obeys | Spontaneous or obeys verbal command | 6 |

| Painful stimulus | Localises pain | Localises pain | 5 |

| Withdraws | Withdraws | 4 | |

| Abnormal flexion | Abnormal flexion (decorticate posture) | 3 | |

| Extension | Abnormal extension (decerebrate posture) | 2 | |

| No response | No response | 1 | |

| Best verbal response | Oriented and converses | Smiles, orientated to sounds, follows objects, interacts | 5 |

| Disoriented and converses | Fewer than usual words, spontaneous irritable cry | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | Cries only to pain | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | Moans to pain | 2 | |

| No response | No response to pain | 1 |

A score of <8 out of 15 means that the child’s airway is at risk and will need to be maintained by a manoeuvre or adjunct.

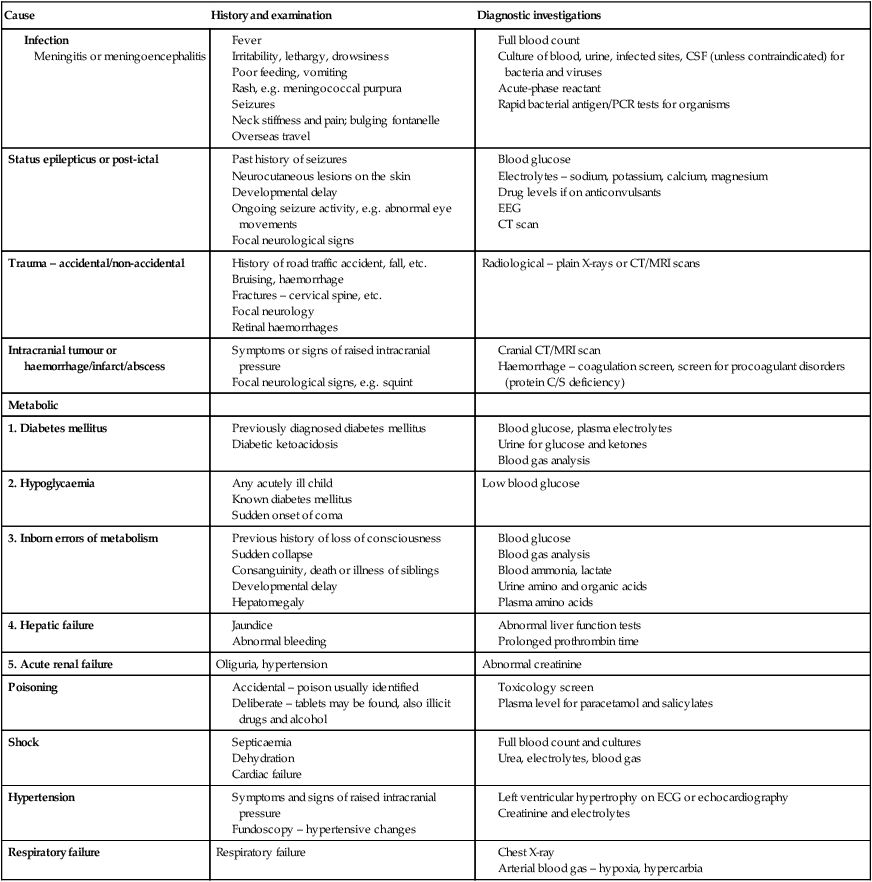

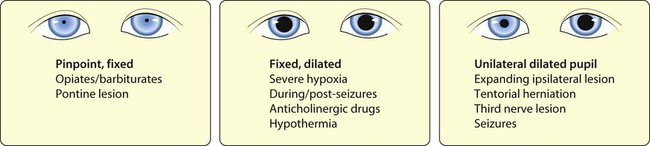

The immediate assessment of a child in coma is shown in Figures 6.10 and 6.11. The causes, clinical features and investigations of coma are listed in Table 6.3. In contrast to adults, most children have a diffuse metabolic insult rather than a structural lesion.

Table 6.3

Causes, history and examination and investigation of coma

| Cause | History and examination | Diagnostic investigations |

• the head end of the bed tilted by 20–30°

• isotonic fluids at 60% maintenance

• intubation and ventilation if Glasgow Coma Score <9

An intracranial mass lesion may require neurosurgical intervention.

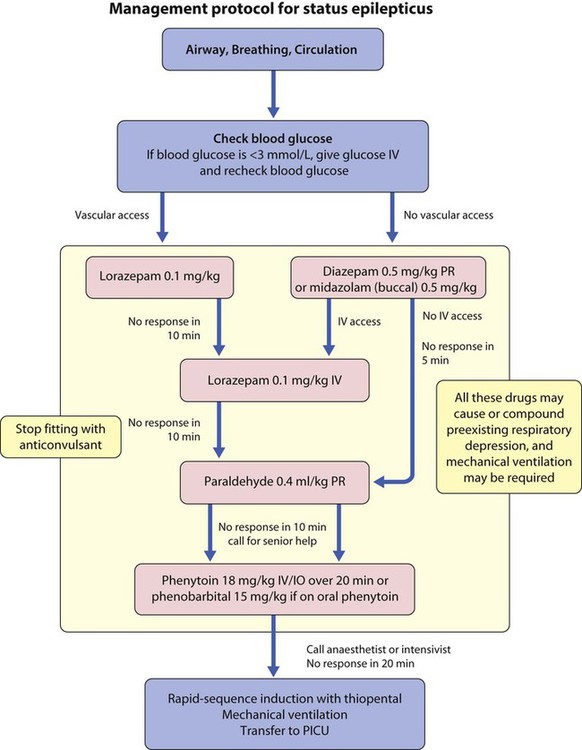

Status epilepticus

This is a seizure lasting 30 minutes or longer, or when successive seizures occur so frequently that the patient does not recover consciousness between them. After immediate primary assessment and resuscitation, the priority is to stop the seizure as quickly as possible (Fig. 6.12).

Anaphylaxis

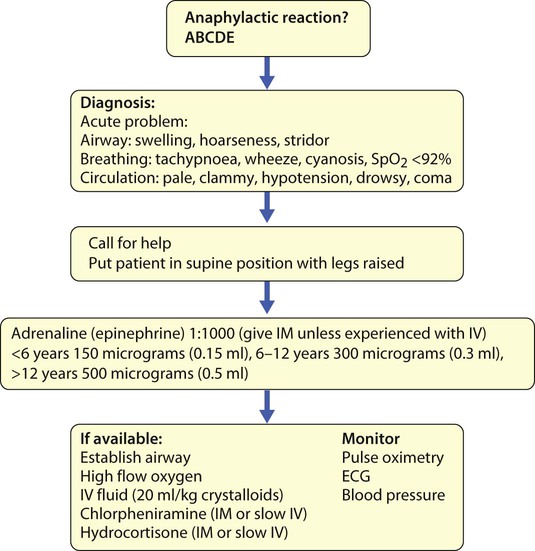

Anaphylaxis is rapid in onset and may be fatal. It has an incidence of one episode every 20 000 person years, and about 1 in 1000 cases are fatal. In children, 85% of anaphylaxis is caused by food allergy; most are IgE-mediated reactions with significant respiratory or cardiovascular compromise. Other causes include insect stings, drugs, latex, exercise, inhalant allergens and idiopathic. While most paediatric anaphylaxis occurs in children <5 years, when food allergy is most prevalent, the majority of fatal paediatric anaphylaxis occurs in adolescents with allergy to nuts; asthma is an additional risk factor. The acute management of anaphylaxis relies on early administration of adrenaline (epinephrine) (Fig. 6.13). Long-term management involves detailed strategies and training for allergen avoidance, a written management plan with instructions for the treatment of allergic reactions and the provision of adrenaline (epinephrine) auto-injector(s). In some cases, such as insect sting anaphylaxis, allergen immunotherapy may be effective in preventing future episodes. The experience of an anaphylactic reaction can have a significant psychological impact on the child and family.

Apparent life-threatening events (ALTE)

Management requires a detailed history and thorough examination to identify problems with the baby or in caregiving. The infant should be admitted to hospital. Causes and investigations to be considered are listed in Box 6.4. Multi-channel overnight monitoring is usually indicated.

The death of a child

Sudden infant death syndrome

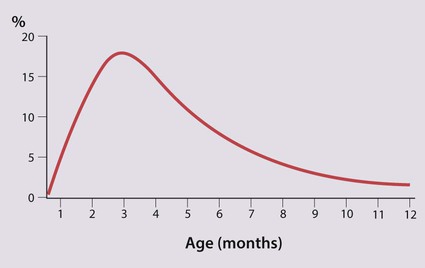

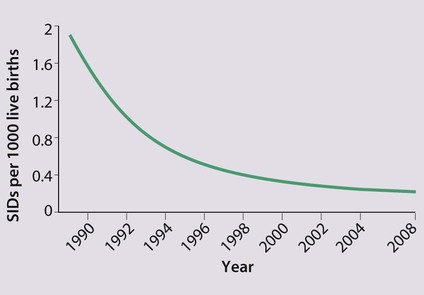

This is defined as the sudden and unexpected death of an infant or young child for which no adequate cause is found after a thorough postmortem examination. There is marked variation in the incidence of SIDS in different countries, suggesting that environmental factors are important (Box 6.5). SIDS occurs most commonly at 2–4 months of age (Fig. 6.14). The risk for subsequent children is slightly increased.

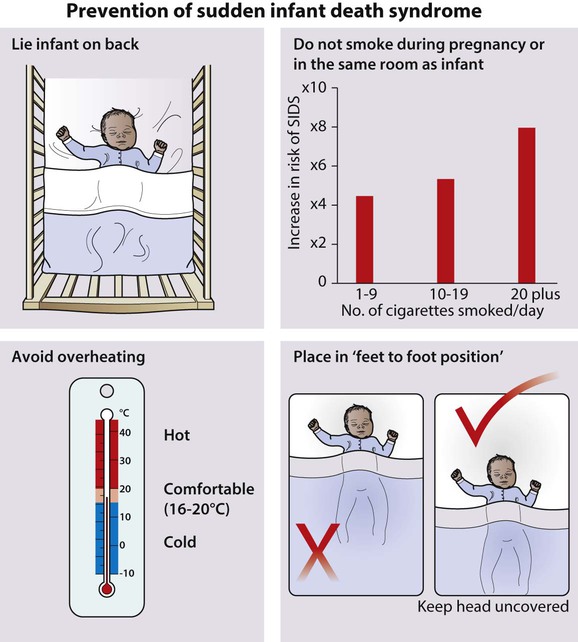

In the UK, the incidence of SIDS has fallen dramatically during the last 20 years (Fig. 6.15), coinciding with a national ‘Back to Sleep’ campaign (Fig. 6.16). This advocates that:

• Infants should be put to sleep on their back (not their front or side)

• Overheating by heavy wrapping and high room temperature should be avoided

• Infants should be placed in the ‘feet to foot’ position

• Parents should not smoke near their infants

• Parents should seek medical advice promptly if their infant becomes unwell.

• Parents should have the baby in their bedroom for the first 6 months of life

• Parents should avoid bringing the baby into their bed when they are tired or have taken alcohol, sedative medicines or drugs

• Parents should avoid sleeping with their infant on a sofa, settee or armchair.

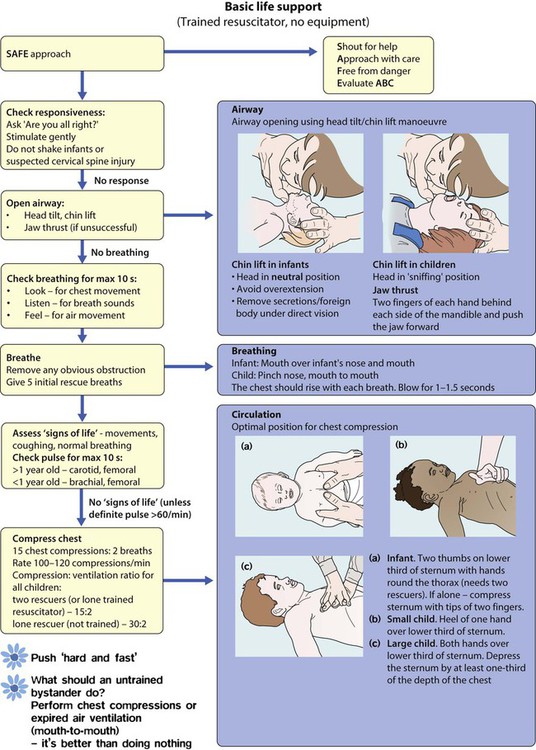

Following the sudden death of a child

The sudden death of a child is one of the most distressing events that can happen to a family. If close family members are absent, arrangements should be made for them to come, if this is possible. The family should be spoken to sympathetically and in private (see Ch. 5). An outline of the recommended management after an infant has died suddenly and unexpectedly is shown in Figure 6.17.