Malignant disease

Cancer in children is not common.

• Around 1 child in 500 develops cancer by 15 years of age.

• Each year, in Western countries, there are 120–140 new cases per million children aged under 15 years, equivalent to about 1500 new cases each year in the UK.

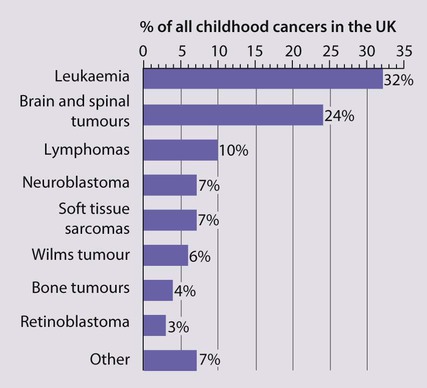

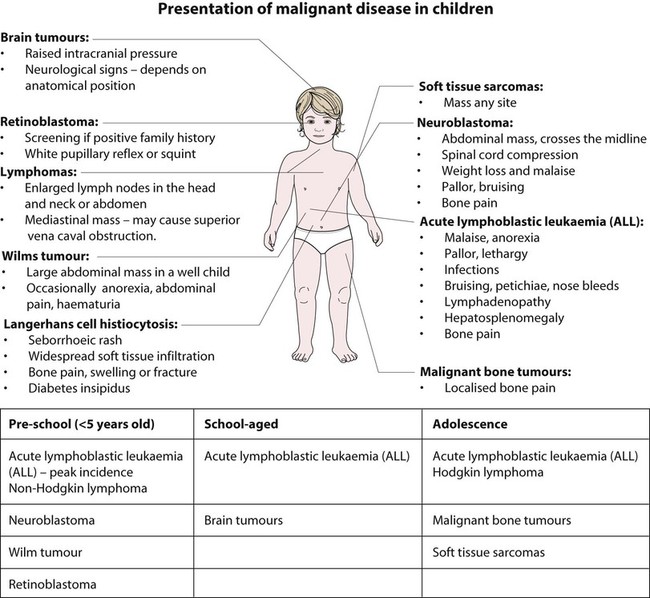

The types of disease seen (Fig. 21.1) are very different from those in adults, where carcinomas of the lung, breast, gut and skin predominate. The age at presentation varies with the different types of disease:

• Leukaemia affects children at all ages (although there is an early childhood peak).

• Neuroblastoma and Wilms tumour are almost always seen in the first 6 years of life.

• Hodgkin lymphoma and bone tumours have their peak incidence in adolescence and early adult life.

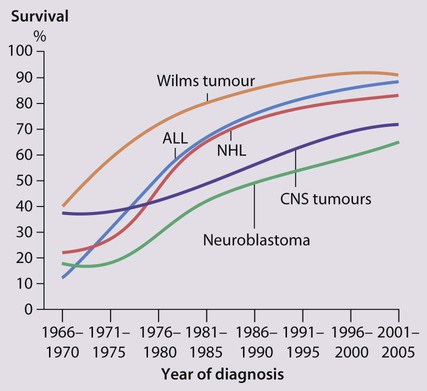

Despite significant improvements in survival over the last four decades (Fig. 21.2), cancer is the commonest disease causing death in childhood (beyond the neonatal period). Overall, the 5-year survival of children with all forms of cancer is about 75%, most of whom can be considered cured, although cure rates vary considerably for different diagnoses. This improved life expectancy can be attributed mainly to the introduction of multi-agent chemotherapy, supportive care and specialist multidisciplinary management. However, for some children, the price of survival is long-term medical or psychosocial difficulties.

Treatment

Treatment may involve chemotherapy, surgery or radiotherapy, alone or in combination.

Chemotherapy

• as primary curative treatment, e.g. in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

• to control primary or metastatic disease before definitive local treatment with surgery and/or radiotherapy, e.g. in sarcoma or neuroblastoma

• as adjuvant treatment to deal with residual disease and to eliminate presumed micrometastases, e.g. after initial local treatment with surgery in Wilms tumour

Supportive care and side-effects of treatment

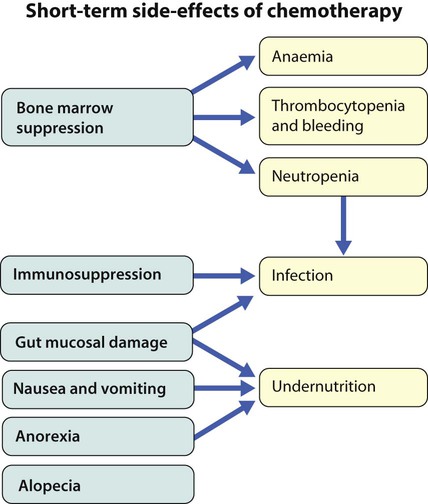

Cancer treatment produces frequent, predictable and often severe multisystem side-effects (Fig. 21.3). Supportive care is an important part of management and improvements in this aspect of cancer care have contributed to the increasing survival rates.

Leukaemia

Clinical presentation

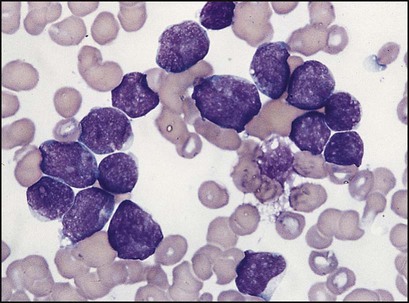

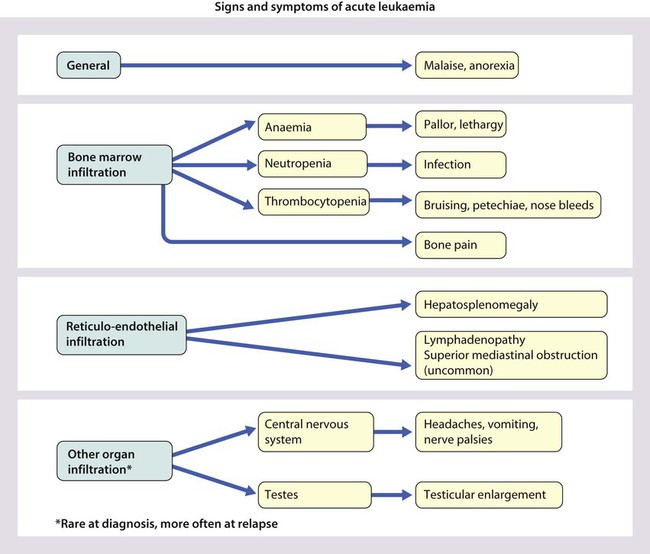

Presentation of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia peaks at 2–5 years. Clinical symptoms and signs result from disseminated disease and systemic ill-health from infiltration of the bone marrow or other organs with leukaemic blast cells (Fig. 21.5). In most children, leukaemia presents insidiously over several weeks (see Case History 21.1) but in some children the illness presents and progresses very rapidly.

Management of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

A number of factors contribute to prognosis in ALL and dictate the intensity of therapy (Table 21.1).

Table 21.1

Prognostic factors in acute lymphatic leukaemia

| Prognostic factor | High-risk features |

| Age | <1 year or >10 years |

| Tumour load (measured by the white cell count, WBC) | >50 × 109/L |

| Cytogenetic/molecular genetic abnormalities in tumour cells | e.g. MLL rearrangement, t(4;11), hypodiploidy (<44 chromosomes) |

| Speed of response to initial chemotherapy | Persistence of leukaemic blasts in the bone marrow |

| Minimal residual disease assessment (MRD) (submicroscopic levels of leukaemia detected by PCR) | High |

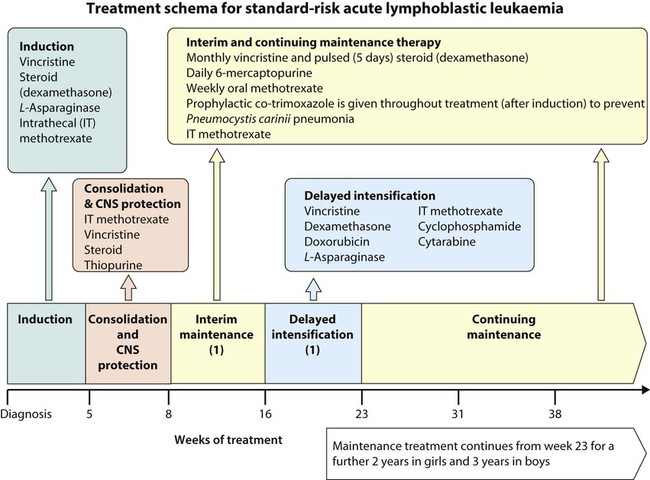

A typical treatment schema is shown in Figure 21.7.

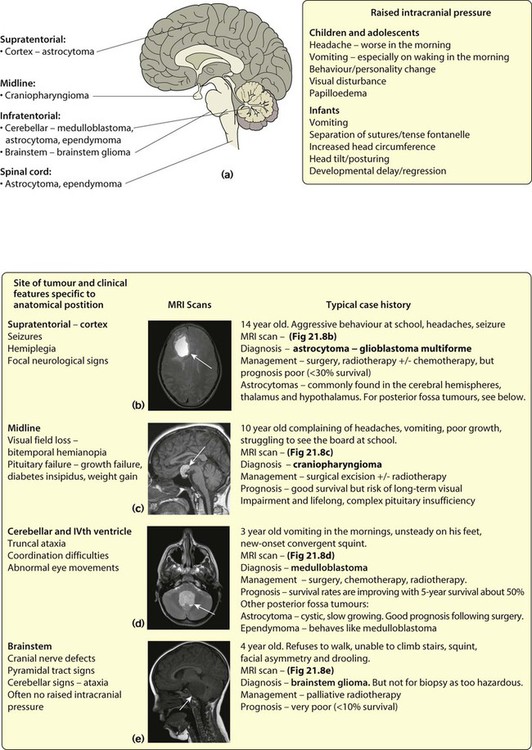

Brain tumours

• Astrocytoma (~40%) – varies from benign to highly malignant (glioblastoma multiforme)

• Medulloblastoma (~20%) – arises in the midline of the posterior fossa. May seed through the CNS via the CSF and up to 20% have spinal metastases at diagnosis

• Ependymoma (~8%) – mostly in posterior fossa where it behaves like medulloblastoma

• Craniopharyngioma (4%) – a developmental tumour arising from the squamous remnant of Rathke pouch. It is not truly malignant but is locally invasive and grows slowly in the suprasellar region.

Lymphomas

Hodgkin lymphoma

Clinical features

Classically presents with painless lymphadenopathy, most frequently in the neck. Lymph nodes are much larger and firmer than the benign lymphadenopathy commonly seen in young children. The lymph nodes may cause airways obstruction (see Case History 21.2). The clinical history is often long (several months) and systemic symptoms (sweating, pruritus, weight loss and fever – the so-called ‘B’ symptoms) are uncommon, even in more advanced disease.

Neuroblastoma

Clinical features

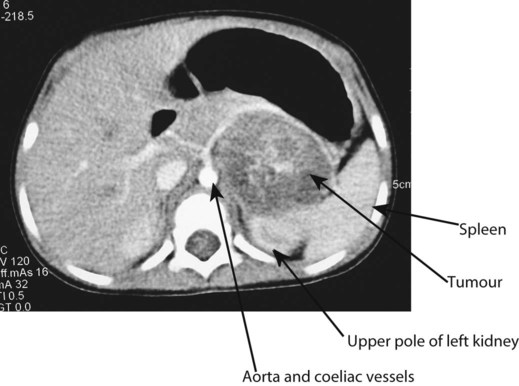

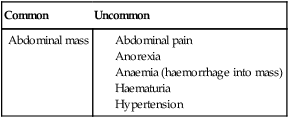

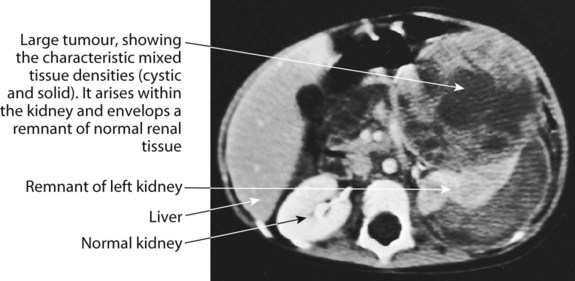

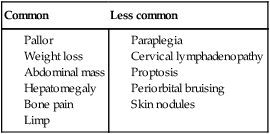

At presentation (Box 21.1), most children have an abdominal mass, but the primary tumour can lie anywhere along the sympathetic chain from the neck to the pelvis. Classically, the abdominal primary is of adrenal origin, but at presentation the tumour mass is often large and complex, crossing the midline and enveloping major blood vessels and lymph nodes. Paravertebral tumours may invade through the adjacent intervertebral foramen and cause spinal cord compression. Over the age of 2 years, clinical symptoms are mostly from metastatic disease, particularly bone pain, bone marrow suppression causing weight loss and malaise (see Case History 21.3).

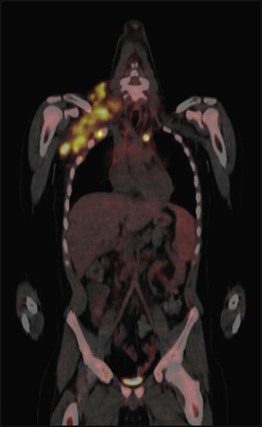

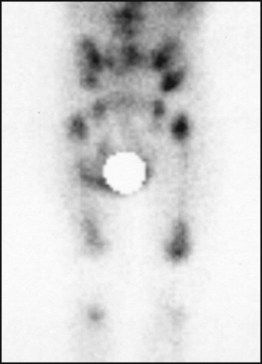

Investigations

Characteristic clinical and radiological features with raised urinary catecholamine levels suggest neuroblastoma. Confirmatory biopsy is usually obtained and evidence of metastatic disease detected with bone marrow sampling, MIBG (metaiodobenzyl-guanidine) scan (as in Fig. 21.12) with or without a bone scan.

Bone tumours

Investigations

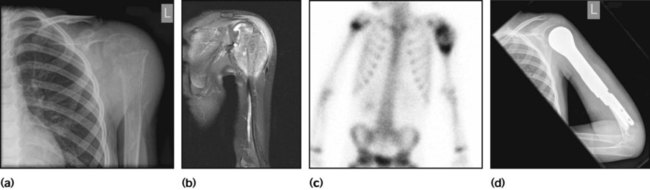

Plain X-ray is followed by MRI and bone scan (Fig. 21.15a–c). A bone X-ray shows destruction and variable periosteal new bone formation. In Ewing sarcoma, there is often a substantial soft tissue mass. Chest CT is used to assess for lung metastases and bone marrow sampling to exclude marrow involvement.

Management

In both tumours, treatment involves the use of combination chemotherapy given before surgery. Whenever possible, amputation is avoided by using en bloc resection of tumours with endoprosthetic resection (Fig. 21.15d). In Ewing sarcoma, radiotherapy is also used in the management of local disease, especially when surgical resection is impossible or incomplete, e.g. in the pelvis or axial skeleton.

Rare tumours

Liver tumours

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

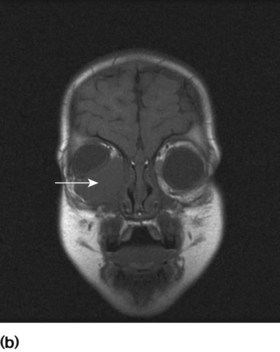

• Bone lesions – present at any age with pain, swelling or even fracture. X-ray reveals a characteristic lytic lesion with a well-defined border, often involving the skull (Fig. 21.17).

• Diabetes insipidus – may be associated with skull disease with proptosis and hypothalamic infiltration

• Systemic LCH – the most aggressive form which tends to present in infancy with a seborrhoeic rash (Fig. 21.18) and soft tissue involvement of the gums, ears, lungs, liver, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow. This form of LCH is usually progressive and requires chemotherapy, although spontaneous regression may occur.

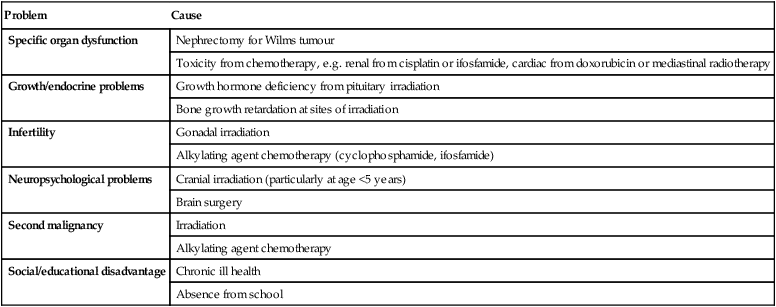

Long-term survivors

Improved survival rates means an ever-increasing population of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Over half have at least one residual problem as a consequence of either the disease or its treatment (Table 21.2).

Table 21.2

Some problems that may occur following cure of childhood cancer

| Problem | Cause |

| Specific organ dysfunction | Nephrectomy for Wilms tumour |

| Toxicity from chemotherapy, e.g. renal from cisplatin or ifosfamide, cardiac from doxorubicin or mediastinal radiotherapy | |

| Growth/endocrine problems | Growth hormone deficiency from pituitary irradiation |

| Bone growth retardation at sites of irradiation | |

| Infertility | Gonadal irradiation |

| Alkylating agent chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide) | |

| Neuropsychological problems | Cranial irradiation (particularly at age <5 years) |

| Brain surgery | |

| Second malignancy | Irradiation |

| Alkylating agent chemotherapy | |

| Social/educational disadvantage | Chronic ill health |

| Absence from school |