Chapter 106 Paediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation

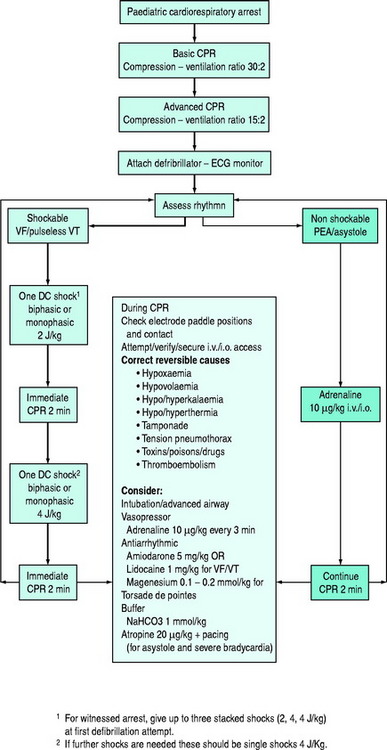

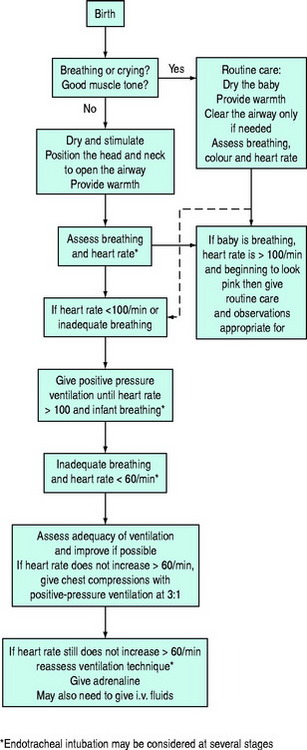

This chapter concerns basic and advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for infants and children (Figure 106.1). The essentials of resuscitation of the ‘newly-born’ (at birth) infant are also provided (Figure 106.2). The recommendations are based on guidelines published by several authoritative resuscitation organisations1–3 which are in turn derived from an extensive evaluation of the science of resuscitation conducted by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation.4

Figure 106.2 Newly-born infant resuscitation.

(Reproduced with permission from the Australian Resuscitation Council, Melbourne.)

BASIC LIFE SUPPORT

RESCUE BREATHING (EXPIRED AIR RESUSCITATION)

If inadequate breathing is present, rescue breathing (expired air resuscitation) or bag-valve-mask ventilation should be commenced immediately. There is no evidence to dictate the number of initial breaths. However, at least two breaths are recommended by all resuscitation organisations, with some stating up to five. While maintaining the airway, slow breaths over 1–1.5 seconds should be given with enough air to achieve adequate chest inflation. In children of all sizes, a mouth-to-mouth technique is possible by pinching the nostrils closed. In newly-born and infants, a mouth-to-mouth-and-nose technique is recommended, but if the rescuer has a small mouth, a mouth-to-nose technique is an alternative. Lack of chest rise may signify obstruction of the airway requiring repositioning of the head and neck.

RATES OF COMPRESSION AND RATIO OF COMPRESSION TO VENTILATION

For infants and children, compressions should be delivered at a rate of 100/min, i.e. one compression every 0.6 seconds or approximately two per second. This does not mean that 100 actual compressions are given each minute. When ventilation is interposed between compressions, the actual compressions delivered will be less than 100 each minute.

ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

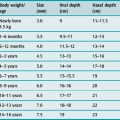

Intubation via the oral route:

On the other hand, a tube placed nasally:

DC SHOCK

In the treatment of refractory arrhythmias, equipment failure should be excluded. An anteroposterior position of the paddles (one over the cardiac apex, one over the left scapula) may be efficacious in refractory arrhythmia. Dextrocardia may be present with congenital heart disease and the position of the paddles should be altered accordingly.

TREATMENT OF SPECIFIC ARRHYTHMIAS

The following discussion of specific arrhythmias assumes that mechanical ventilation with oxygen and external cardiac compression has been commenced. The treatment of pulseless arrhythmias is summarised in Figure 106.1.

Reversible causes of arrhythmias should be sought and treated during resuscitation. For example:

VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION AND PULSELESS VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

Failure to revert to sinus rhythm should be treated with adrenaline 10 μg/kg i.v. or i.o. or 100 μg/kg ETT and another shock at 4 J/kg after an interval of ECC. Persistent (refractory) or recurrent VF or VT may also be treated with antiarrhythmics (amiodarone, lidocaine, magnesium) interspersed with single DC shocks. Irrespective of other drug therapy, adrenaline should be administered every 3–5 minutes. The dose of lidocaine is 1 mg/kg i.v. or i.o. bolus followed by an infusion if successful at 20–50 μg/kg per min. The dose of amiodarone is 5 mg/kg i.v. or i.o. as a bolus which may be repeated to maximum of 15 mg/kg. Magnesium, 25–50 mg/kg (0.1–0.2 mmol/kg) is indicated for polymorphic VT (torsade de pointes). The alternative to adrenaline as a vasopressor, vasopressin, has not been adequately investigated for use during CPR for children.

POST RESUSCITATION CARE

POST RESUSCITATION STAFF MANAGEMENT

Unfortunately, CPA occurring in hospital is often unexpected – for example, when a moribund patient arrives unannounced in the emergency department, a patient’s condition deteriorates rapidly on the ward or when a mishap occurs under anaesthesia. These situations test the readiness, training, abilities and skills of individuals and the organisation of the institution. It is prudent to monitor performance with a view to improvement and not ignore the psychological impact which such events have on individuals. Sensitive debriefing sessions should be encouraged.

1 Australian Resuscitation Council, Melbourne. http://www.resus.org.au. Guidelines 12.1–12.7, 13.1–13.10.

2 American Heart Association. Pediatric advanced life support. Circulation. 2005;112:167-187.

3 European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2005. Section 6. Paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S97-S133.

4 International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Consensus on resuscitation science and treatment recommendations. Part 6. Paediatric basic and advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2005;67:271-291.