Chapter 2 Outreach

CRITICAL CARE OUTREACH

A key innovation in critical care has been the development of dedicated outreach and medical emergency/rapid response services aiming ‘to ensure equity of care for all critically ill patients irrespective of their location’.1

Outreach is multidisciplinary ‘collaboration and partnership between critical care and other departments to ensure a continuum of care for patients and to enhance the skills and understanding of all staff in the delivery of critical care’.2 Outreach services primarily focus on patients with potential or actual critical illness on general wards. They are not a substitute for insufficient critical care beds, poor ward facilities or inadequate staffing.

BACKGROUND

Many patients who require critical care are on a ward for part of their hospital admission. Comparison of outcomes of patients admitted to a critical care unit from the emergency department, operating theatre/recovery area and wards shows that the highest number of deaths is found in patients admitted from wards.3 The longer patients are in hospital before admission to critical care, the higher their mortality.4 Reports from many countries show that hospital patients frequently suffer adverse events and that these events can cause major morbidity or death.5 Suboptimal treatment is common before admission to critical care and is associated with worse outcomes.6 Crucially, the baseline characteristics of patients who receive suboptimal care are not significantly different from those who are well managed. Differences in mortality are attributable to differences in the quality of care rather than differences between patients themselves. Many factors are implicated, including lack of knowledge and failure to appreciate clinical urgency and to seek advice, compounded by poor organisation, breakdown in communication and inadequate supervision.

About one-quarter of all ‘critical care deaths’ occur after patients have been discharged back to wards from critical care. Patients discharged inappropriately early have an increased mortality.7,8 There are also deaths among surgical patients who have returned to the ward following surgery without ever being admitted to critical care.

OUTREACH SYSTEMS

Medical emergency teams (METs) were first introduced in Australia in 1990. METs expanded the role of the hospital cardiac arrest team to include the pre-arrest period, with call-out criteria generally based upon markedly deranged physiological values.9 In the UK, critical care outreach (CCO) services became relatively widespread following negative publicity about shortages of critical care facilities and the national review of critical care services in 2000.10 This led to some additional funding for critical care beds and outreach services. Other countries have also recognised the needs of critically ill patients outside designated critical care areas and have introduced their own systems to address these problems.

There are now many models and a variety of terms for outreach services.11,12 Some organisations have enthusiastically embraced the concept whereas others have reservations. METs are usually physician-led, while CCO teams and rapid response teams (RRTs) are typically nurse-led but may include physiotherapists and other allied health professionals as well as doctors. Most teams respond to defined triggers, although some, particularly CCO services, also work proactively with known at-risk patients such as intensive care unit (ICU) discharges.

These systems have the following features in common:

The aim is to prevent unnecessary critical care admissions, to ensure timely transfer to critical care when needed, to facilitate safe discharge from critical care back to the ward, to share critical care skills and to improve standards of care throughout the hospital. There may also be a role in outpatient support for patients and their families after hospital discharge (Table 2.1).

|

• Education for ward staff in recognition of fundamental signs of deterioration, and in understanding how to obtain appropriate help promptly

|

RECOGNISING CRITICAL ILLNESS

Critically ill patients are identified by review of the history, by examination and investigations. Higher risks are associated with extremes of age, with significant comorbidities or with serious presenting conditions. Outcome is often related to and can be predicted by abnormal physiology. Many studies show patients have abnormal physiology for hours and sometimes days before critical events such as cardiopulmonary arrest.13–18 However, measuring and recording of vital signs on general wards are often inadequate.19

A physiologically based system for identifying critical illness should have certain attributes (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Ideal attributes of an early-warning (track and trigger) scoring system

| Timely | Measurable |

| Reliable | Reproducible |

| Inexpensive | Non-invasive |

| Repeatable | Safe |

| Accurate | Independent of disease state |

ABNORMAL PHYSIOLOGY AND ADVERSE OUTCOME

There is an association between abnormal physiology and adverse outcome. Critical care severity scoring systems such as Acute Physiology, Age and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II)20 are based on this relationship. Patients who suffer cardiopulmonary arrest or who die in hospital generally have abnormal physiological values recorded in the preceding period, as do patients requiring transfer to the critical care unit.

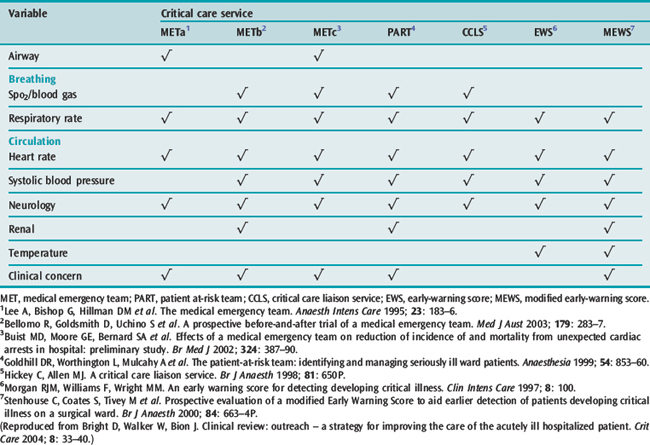

It therefore follows that vital signs can predict many adverse events. These principles have been incorporated into a number of early-warning scoring (EWS) systems. The systems incorporate different combinations of physiological parameters, a range of approaches to scoring and various trigger thresholds. Examples of the variables included in a few of the scoring systems are given in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3 Variables used by different scoring systems to trigger referrals to a critical care service

In the UK these methods are often called track and trigger warning systems. They can be broadly summarised as single-parameter systems, multiple-parameter systems, aggregate weighted scoring systems or combinations (Table 2.4).1

Table 2.4 Classification of track and trigger warning systems

| Single-parameter systems |

| Tracking |

| Periodic observation of selected basic signs |

| Trigger |

| One or more extreme observational values |

| Multiple-parameter systems |

| Tracking |

| Periodic observation of selected basic vital signs |

| Trigger |

| Two or more extreme observational values |

| Aggregate weighted scoring systems |

| Tracking |

| Periodic observation of selected basic vital signs and the assignment of weighted scores to physiological values with calculation of a total score |

| Trigger |

| Achieving a previously agreed trigger threshold with the total score |

| Combination systems |

| Elements of single- or multiple-parameter systems in combination with aggregate weighted scoring |

(Definitions taken from Department of Health/Modernisation Agency. Critical Care Outreach 2003 – Progress in Developing Services: National Outreach Report. London: Department of Health, 2003.)

In Australia, MET call-out criteria are usually based upon markedly deranged physiological values, although ward staff concern is also a trigger (Table 2.5).21

Table 2.5 Medical emergency team call-out criteria

| Airway | Respiratory distress |

| Threatened airway | |

| Breathing | Respiratory rate < 6 or > 30 breaths/min |

| SpO2 < 90% on oxygen | |

| Difficulty speaking | |

| Circulation | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg despite treatment |

| Heart rate > 130 beats/min | |

| Neurology | Unexplained decrease in consciousness |

| Agitation or delirium | |

| Repeated or prolonged seizures | |

| Other | Concern about patient |

| Uncontrolled pain | |

| Failure to respond to treatment | |

| Unable to obtain prompt help |

(Call-out criteria from Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA et al. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. Br Med J 2002; 324: 387–90.)

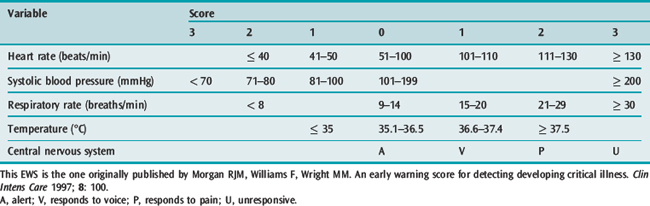

The use of physiological values in the form of a multiple-parameter EWS to identify at-risk ward patients was first described by Morgan et al.22 There are different formats but they follow a similar theme, awarding points for varying degrees of derangement of different physiological functions (Table 2.6). The higher the total score, the more the patient is ‘at risk’.

MEASURING OUTCOME

The concept of outreach is based upon the premise that early detection and treatment of critical illness should improve patient outcomes. The quality of an outreach service may be evaluated against these and other measures, including indicators of effective processes (Table 2.7).

Outreach systems have certainly highlighted shortcomings in the care of ward patients and contributed to a change in attitude and more attention to at-risk patients. They have been instrumental in improving ward monitoring and charting and in disseminating critical care skills. There is much anecdotal evidence of benefit to individual patients. There is published evidence that outreach services improve the recognition of at-risk patients on wards and can reduce length of stay, cardiac arrest rates, unplanned admissions to critical care and morbidity and mortality of such patients.21,23–26 However, there are as many reports that do not show significant effects. In fact there are as yet few good-quality studies, with just two randomised controlled trials.26,27

Positive studies include a UK randomised trial of phased introduction of a 24-hour outreach service to 16 wards in a general acute hospital.26,28 The outreach team routinely followed up patients discharged from critical care to the wards and saw referrals generated by ward staff concern or use of an aggregate weighted scoring system. There was a statistically significant reduction in hospital mortality in wards where the service was operational. In contrast, a large prospective randomised trial of METs in Australia did not find improvements in cardiac arrests, unplanned admissions to critical care or unexpected deaths.27 The study did reveal many shortcomings in the identification and care of critically ill patients. One possible conclusion is that for outreach to work there must be a whole-systems approach to early identification of at-risk patients and to obtaining an appropriate, timely and effective response.

It can be argued that outreach should not be necessary in a properly run and funded first-world health care system. Time will tell if outreach services are simply a stopgap solution to compensate for hospital system failings. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that there are significant numbers of patients on hospital wards with potential or actual critical illness whose care should and could be improved. Outreach systems are one method of addressing these issues.

SETTING UP AN OUTREACH SERVICE

Patients with potential or actual critical care illness may be found in almost every area of the acute hospital, so systems to identify and treat at-risk patients promptly and improve quality across an institution need to be planned at an organisational level. Involvement of managerial and clinical staff at all levels, particularly from the general wards, is essential. It is particularly important that there is agreement and clarity about how the outreach team interacts with the parent/primary medical team. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has useful information on setting up a rapid response team.29

KEY STEPS IN PLANNING AN OUTREACH SERVICE

THE OUTREACH TEAM

A pragmatic, staged implementation could include:

1 Department of Health and Modernisation Agency. The National Outreach Report 2003. Department of Health: London, 2003.

2 The Intensive Care Society. Guidelines for the Introduction of Outreach Services. Intensive Care Society: London, 2002.

3 Goldhill DR, Sumner A. Outcome of intensive care patients in a group of British intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1337-1345.

4 Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Hadjianastassiou VG, et al. The longer patients are in hospital before intensive care admission the higher their mortality. Intens Care Med. 2004;30:1908-1913.

5 Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospital: preliminary retrospective record review. Br Med J. 2001;322:517-519.

6 McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, et al. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. Br Med J. 1998;316:1853-1858.

7 Daly K, Beale R, Chang RW. Reduction in mortality after inappropriate early discharge from intensive care unit: logistic regression triage model. Br Med J. 2001;322:1274-1276.

8 Goldfrad C, Rowan K. Consequences of discharges from intensive care at night. Lancet. 2000;355:1138-1142.

9 Lee A, Bishop G, Hillman KM, et al. The medical emergency team. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23:183-186.

10 Department of Health. Comprehensive Critical Care. A Review of Adult Critical Care Services. Department of Health: London, 2000.

11 DeVita MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, et al. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2463-2478.

12 Esmonde L, McDonnell A, Ball C, et al. Investigating the effectiveness of critical care outreach services: a systematic review. Intens Care Med. 2006;32:1713-1721.

13 Berlot G, Pangher A, Petrucci L, et al. Anticipating events of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:24-28.

14 Buist MD, Jarmolowski E, Burton PR, et al. Recognising clinical instability in hospital patients before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care. A pilot study in a tertiary-care hospital. Med J Aust. 1999;171:22-25.

15 Harrison GA, Jacques TC, Kilborn G, et al. The prevalence of recordings of the signs of critical conditions and emergency responses in hospital wards – the SOCCER study. Resuscitation. 2005;65:149-157.

16 Jacques T, Harrison GA, McLaws ML, et al. Signs of critical conditions and emergency responses (SOCCER): a model for predicting adverse events in the inpatient setting. Resuscitation. 2006;69:175-183.

17 Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom – the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004;62:275-282.

18 Cullinane M, Findlay G, Hargraves C, et al. An acute problem. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death: London, 2005.

19 Audit Commission. Critical to Success. National Health Service in England and Wales: Audit Commission for Local Authorities and the London, 1999.

20 Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818-829.

21 Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, et al. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. Br Med J. 2002;324:387-390.

22 Morgan RJM, Williams F, Wright MM. An early warning score for detecting developing critical illness. Clin Intens Care. 1997;8:100.

23 Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179:283-287.

24 Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:916-921.

25 Ball C, Kirkby M, Williams S. Effect of the critical care outreach team on patient survival to discharge from hospital and readmission to critical care: non-randomised population based study. Br Med J. 2003;327:1014-1017.

26 Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trail of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intens Care Med. 2004;30:1398-1404.

27 Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2091-2097.

28 Watson W, Mozley C, Cope J, et al. Implementing a nurse-led critical care outreach service in an acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:105-110.

29 Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/Changes/EstablishaRapidResponseTeam.htm. Accessed 4 December 2006