68

Other Viral Diseases

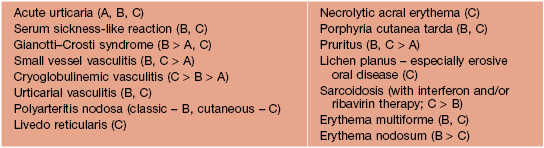

Viral infections frequently have cutaneous manifestations, especially in children. This chapter covers classic childhood exanthems, poxvirus infections, and several other viral infections with characteristic skin findings. Nonspecific viral exanthems, typically presenting with blanchable erythematous macules and papules in a widespread distribution, are also common in children infected with enteroviruses (see below) and a variety of respiratory viruses, generally resolving spontaneously within a week. Fig. 68.1 outlines clinical features to consider when evaluating a patient with a morbilliform (‘maculopapular’) exanthem, and Chapter 3 addresses considerations in patients with fever and a rash. HIV, human papillomavirus, and herpesvirus (including infectious mononucleosis and roseola infantum) infections are discussed in Chapters 65–67.

Fig. 68.1 Approach to the patient with a presumed morbilliform or macular/papular viral exanthem. *Gram-positive rod; may result in severe pharyngitis and scarlatiniform exanthem in adolescents and young adults. †Intracellular inclusions in endothelial cells are another finding. **Usually febrile seizures.

Enterovirus Infections

• Hand, foot, and, mouth disease (HFMD; in the United States, coxsackievirus A16 > others) features oval vesicles on the hands and feet (palms/soles > dorsally) and buttocks plus an erosive stomatitis (e.g. tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, tonsils), often associated with fever and malaise (Fig. 68.2A–D); onychomadesis occasionally occurs 1–2 months later.

Fig. 68.2 Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD). A Oval vesicle and erythematous macules on the plantar surface. B Multiple erythematous macules on the palm, some with a dusky appearance reminiscent of erythema multiforme. C Small oval erosions on the buccal mucosa resembling aphthae. D Discrete erythematous papules and crusted erosions in an area of previous diaper dermatitis. The differential diagnosis in this patient with coxsackievirus A6 infection might include eczema herpeticum. E Extensive vesicles and crusts in the perioral area in a patient with HFMD due to coxsackievirus A6. Herpes simplex virus infection or impetigo may be considered in the differential diagnosis for lesions in this location. Note koebnerization to the site of a healing laceration on the chin. A, B, D, E, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• Recently, coxsackievirus A6 infection has been associated with a more widespread vesiculobullous exanthem favoring the perioral area, extremities > trunk, and areas of previous dermatitis (‘eczema coxsackium’) or injury as well as the classic sites of HFMD (Fig. 68.2B, D, E; see Fig. 3.5B, C).

• Herpangina presents with fever and oropharyngeal erosions, but usually no exanthem.

• The diverse spectrum of enteroviral exanthems also includes morbilliform, scarlatiniform, Gianotti–Crosti syndrome-like, petechial, and pustular eruptions (see Fig. 3.5A); eruptive pseudoangiomatosis is an uncommon manifestation.

Measles (Rubeola)

• Highly contagious and spread by respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of 10–14 days.

• An exanthem develops 3–5 days after the onset of symptoms, with erythematous macules and papules spreading cephalocaudally from the forehead, hairline, and behind the ears to the trunk and extremities (Fig. 68.3); after 5 days, the eruption fades in the order it appeared.

• Rx: vitamin A administration for children with acute disease; prevention via vaccination.

Rubella (German Measles)

• Spread via respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of 16–18 days.

• Congenital rubella syndrome, most common with maternal infection in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy; can result in cataracts, deafness, congenital heart defects, and microcephaly; a ‘blueberry muffin baby’ presentation occasionally occurs (see Fig. 67.15).

Parvovirus B19 Infection (Erythema Infectiosum, Fifth Disease, ‘Slapped Cheek Disease’)

• Single-stranded DNA virus with tropism for erythroid progenitor cells; found worldwide.

• A mild prodrome (e.g. low-grade fever, myalgias, headache) is followed in 7–10 days by bright red, macular erythema on the cheeks; a few days later, a lacy, reticulated pattern of erythematous macules and papules may appear on the extremities > trunk, lasting 1–3 weeks and fluctuating in intensity (with flares upon sun exposure and overheating) (Fig. 68.4).

Fig. 68.4 Erythema infectiosum. Bright macular erythema on the cheeks, with characteristic sparing of periorificial areas (A). Lacy, reticulated erythematous eruption on the thigh (B) and arms (C) during the second stage of the exanthem. A, Courtesy, Louis Fragola, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• Papular–purpuric gloves and socks syndrome (parvovirus B19 > other viruses) features painful acral edema, erythema, and petechiae/purpura (especially on the palms and soles; Fig. 68.5).

Fig. 68.5 Papular–purpuric gloves and socks syndrome. Erythematous patches with petechiae on the plantar surface. Courtesy, Anthony Mancini, MD.

• More widespread petechial eruptions and an enanthem (petechiae, erosions) can also occur.

Unilateral Laterothoracic Exanthem (Asymmetric Periflexural Exanthem of Childhood)

• A consistent causative infectious agent has not been identified.

• Most often occurs in the spring and favors preschool-aged children.

• Morbilliform or eczematous eruption that begins unilaterally (axilla > trunk or thigh) and then spreads to contralateral sites (Fig. 68.6).

Fig. 68.6 Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Erythematous macules and papules involving the left axilla and upper flank (A) and a slightly more extensive distribution on the left lateral trunk (B).

• Often pruritic and may be preceded by upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Gianotti–Crosti Syndrome (Papular Acrodermatitis of Childhood)

• Most common in the spring and early summer, favoring young children.

• Often preceded by a low-grade fever and/or upper respiratory symptoms.

• Rapid onset of monomorphic, skin-colored to pink-red, edematous papules > papulovesicles in a symmetric distribution on the extensor surfaces of the extremities, buttocks, and face (Fig. 68.7); pruritus, purpuric lesions, and extension to the trunk occasionally occur.

Molluscum Contagiosum (MC)

• Common cutaneous infection caused by a poxvirus.

• Spread by skin-to-skin contact > fomites (e.g. towels), favoring young children but also occurring via sexual contact in adults; larger and more numerous lesions may be seen in immunocompromised hosts, especially those with HIV infection.

• Firm, skin-colored to pink papules or papulonodules with a waxy surface and central umbilication; predilection for the skin folds (e.g. axillae, neck, groin), lateral trunk, thighs, buttocks, genitals, and face (Fig. 68.8).

Fig. 68.8 Molluscum contagiosum. Multiple pearly, umbilicated papules in the genital area (A) and on the face (B); note the inflamed lesion on the right cheek. Inflammatory reactions are a sign of the host immune response to the virus. C Inflamed lesions surrounded by ‘molluscum dermatitis.’ D Furuncle-like presentation of an inflamed molluscum. A culture revealed only normal skin flora. E Monomorphic eruption of pruritic pink papules with crusting on the elbow. These reactive lesions were also present on knees of this child with molluscum contagiosum on the trunk. A, C, Courtesy, Anthony Mancini, MD; B, D, E, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Inflammatory reactions frequently occur, including eczematous dermatitis (diffuse or nummular) in the skin surrounding MC lesions, furuncle-like inflammation of individual MC lesions, and a Gianotti–Crosti syndrome-like eruption of pruritic erythematous papules favoring the elbows and knees (see Fig. 68.8B–E).

• Microscopic evaluation following curettage of lesional contents or biopsy shows large, round intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (see Chapter 2); dermoscopy can identify a characteristic yellow-white, lobular central structure surrounded by a ‘crown’ of blood vessels.

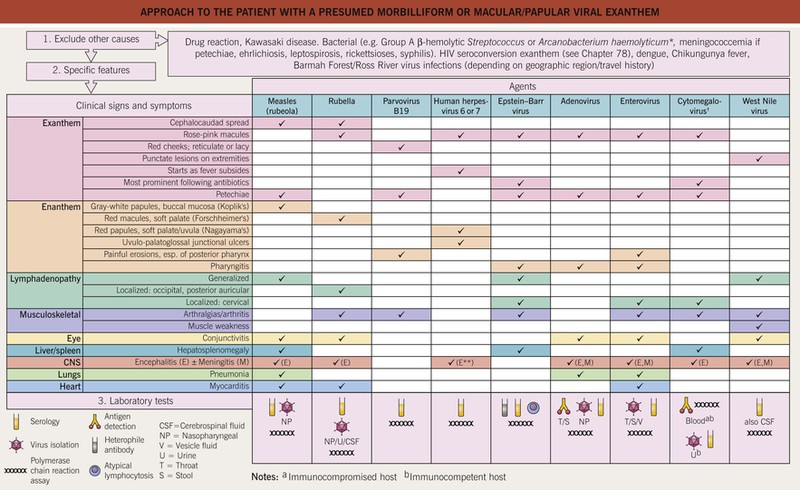

• Rx: options are listed in Table 68.1.

Table 68.1

Treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

Other options include topical sinecatechins, intralesional immunotherapy with Candida antigen, pulsed dye laser, and (for extensive lesions) systemic medications (e.g. oral cimetidine or [in immunosuppressed patients] intravenous cidofovir). Key to evidence-based support: (1) prospective controlled trial; (2) retrospective study or large case series; (3) small case series or individual case reports.

* Discomfort can be minimized by prior application of a topical anesthetic (e.g. lidocaine 4–5% cream).

** Based on publications, but ineffective in 2 unpublished randomized controlled trials.

Other Poxvirus Infections

• The clinical manifestations of smallpox and varicella are compared in Table 68.2, and selected poxvirus infections and complications of smallpox vaccination are presented in Figs. 68.9, 68.10 and Table 68.3.

Table 68.2

Comparison of varicella/disseminated zoster to smallpox.

| Varicella/Disseminated Zoster | Smallpox | |

| Prodrome | None or mild fever and malaise | Fever ≥101°F/38.3°C for 1–4 days prior to rash onset, plus malaise, headache, backache and/or abdominal pain |

| Distribution of lesions | Initially on face/scalp; trunk > distal extremities May have an enanthem |

Concentrated on face and limbs; can progress to involve entire body surface Oropharyngeal lesions often precede cutaneous eruption |

| Stage of lesions | Different stages occur simultaneously in any one area of the skin (nonsynchronous) | Adjacent lesions are all at same stage of development (synchronous) |

| Types of lesions | Superficial papules, vesicles, and pustules | Papulovesicles → firm, deep-seated pustules with a tendency to confluence |

| Course | Lesions appear in crops over a 3-day period | Lesions spread over 1–2 weeks Crusting develops over 1 week |

| Scarring | Rare in uncomplicated cases | Common and marked |

Fig. 68.9 Smallpox vaccine. A Crusted papule at the site of vaccination, 14 days following administration. B Eczema vaccinatum in a patient with atopic dermatitis. Spread from the vaccination site (arrow) to areas of eczema. C Erythema multiforme-like reaction associated with marked erythema and edema at the vaccination site. B, C, Courtesy, Louis Fragola, MD.

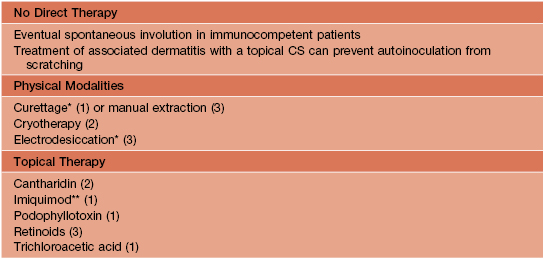

Table 68.3

Selected poxvirus infections.

Real-time PCR is currently the diagnostic method of choice. Other poxviruses that occasionally lead to skin lesions (single or few) in humans include deer-associated parapoxvirus (eastern United States; reported in deer hunters) and tanapox (equatorial Africa; endemic in nonhuman primates, likely arthropod vector).

* Additional information (e.g. diagnostic criteria, algorithms, case definitions) is available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox.

LAN, lymphadenopathy.

Hemorrhagic Fevers and Other Viral Infections with Cutaneous Manifestations

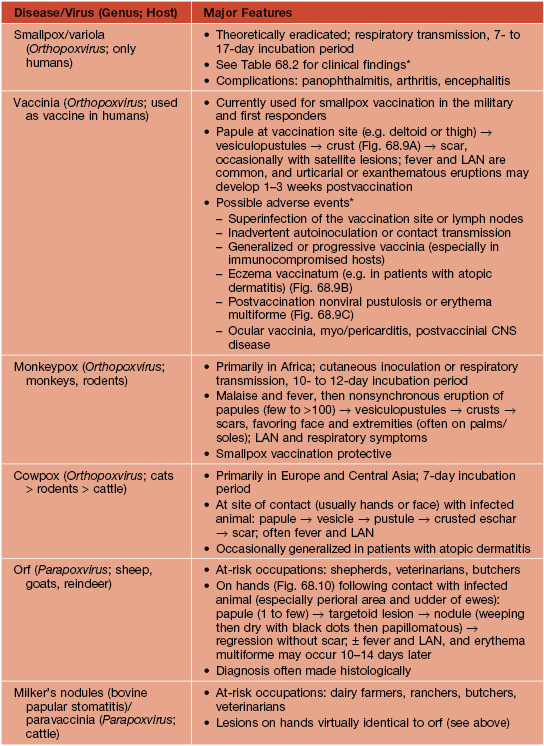

• Cutaneous manifestations of hepatitis A, B, and C infections are listed in Table 68.4.

• Major features of other viral infections with cutaneous findings are presented in Table 68.5.

Table 68.5

Additional viral infections with cutaneous findings.

Other viruses with limited geographic distributions have prominent skin findings, e.g. Barmah Forest virus in Australia.

* In the hemorrhagic form (often representing a repeat infection with a second serotype) marked thrombocytopenia with bleeding into skin and other organs.

** In solid organ transplant recipients or patients receiving chemotherapy for a hematologic malignancy.

For further information see Ch. 81. From Dermatology, Third Edition.