Orthopaedic Pathology

section 1 Introduction

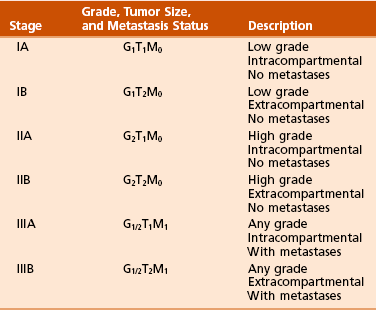

A Enneking system: This staging system can be synthesized into six distinct stages (Table 9-1).

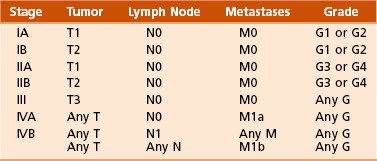

B Variables of AJCC system: The most recent edition of the AJCC system has become more popular than Enneking’s system among medical oncologists and many orthopaedic oncologists. A working knowledge of both systems is necessary for examinations. To use this system, the clinician must know the grade, the size, the presence or absence of discontinuous tumor (skip metastases), and the absence or presence of systemic metastases. The various stages are listed in Table 9-2. The order of importance for the variables of the AJCC staging system is as follows: stage (takes into account all factors), presence of metastases, discontinuous tumor, grade, and size.

Table 9-2

From American Joint Committee on Cancer: Bone. In Greene FL, et al, editor: AJCC cancer staging manual, New York, 2002, Springer-Verlag, pp 213-219.

A Most grading systems are based on three grades:

B The grade of the tumor is most strongly correlated with the potential for metastasis:

1. Grade I (low grade): less than 10% potential

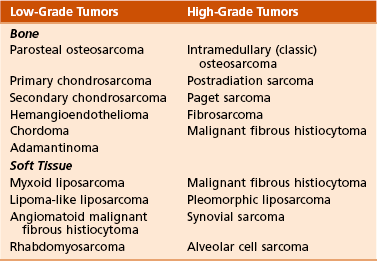

C Most malignant lesions are high grade (Enneking grade G2); low-grade malignant (Enneking grade G1) lesions are less common. Commonly graded lesions are shown in Table 9-3.

A Within the bone compartment (intracompartmental, or T1)

B Extending beyond the confines of the bone (extracompartmental, or T2)

A Chest radiograph and CT scan of the chest are obtained to search for pulmonary lesions.

B Technetium-labeled bone scan is obtained to exclude the presence of other bone lesions.

A Clinical presentation: Most patients with bone tumors present with musculoskeletal pain. However, the most common presentation of a benign bone tumor in childhood is as an incidental finding.

1. Pain is typically deep-seated and may resemble a that of a toothache.

2. Pain may initially be intermittent and related to activity, a work injury, or a sporting injury.

3. Pain usually progresses in intensity and becomes constant.

4. Patients experience pain at night.

5. Pain progresses, and it is not relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or weaker narcotics (such as acetaminophen [Tylenol] with codeine).

6. Patients with a high-grade sarcoma present with a 1- to 3-month history of pain.

7. With low-grade tumors, such as chondrosarcoma, adamantinoma, and chordoma, there may be a long history of mild to moderate pain (6 to 24 months).

B Physical examination: Patients with suspected bone tumors should be examined carefully.

1. Site is inspected for soft tissue masses, overlying skin changes, adenopathy, and general musculoskeletal condition.

2. When metastatic disease is suspected, the thyroid gland, abdomen, prostate, and breasts should be examined, as appropriate.

C Imaging studies: Radiographs in two planes are the first imaging studies to be performed. When the clinician suspects malignancy but the radiographs are normal, selected studies may follow.

1. Technetium-labeled bone scan is an excellent modality to search for occult bone involvement. In patients with myeloma for whom scan results may be negative, a skeletal survey is more sensitive.

2. MRI is an excellent modality for screening the spine for occult metastases, myeloma, or lymphoma.

3. A chest radiograph should be obtained for patients of any age when the clinician suspects a malignant lesion.

4. The radiographs must be carefully inspected to formulate a working diagnosis. The working diagnosis then guides the clinician during further evaluation and treatment. Formulation of the differential diagnosis is based on several clinical and radiographic parameters:

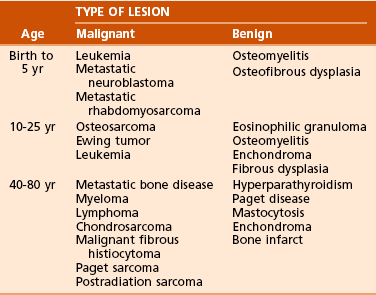

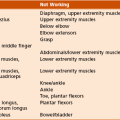

Age of the patient: Knowledge of common diseases in defined age groups is the first step. Certain diseases are uncommon in particular age groups (Table 9-4).

Age of the patient: Knowledge of common diseases in defined age groups is the first step. Certain diseases are uncommon in particular age groups (Table 9-4).

Number of bone lesions: Is the process monostotic or polyostotic? If there are multiple destructive lesions in middle-aged and older patients (ages 40 to 80 years), the most likely diagnosis is metastatic bone disease, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. In young patients (ages 15 to 40 years), multiple lytic and oval lesions in the same extremity are probably vascular tumors (hemangioendothelioma). In children younger than 5 years, multiple destructive lesions may represent metastatic disease such as neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans cell histiocytosis [LCH]) may also lead to multiple lesions in the young patient. Fibrous dysplasia and Paget disease may manifest with multiple lesions in all age groups.

Number of bone lesions: Is the process monostotic or polyostotic? If there are multiple destructive lesions in middle-aged and older patients (ages 40 to 80 years), the most likely diagnosis is metastatic bone disease, multiple myeloma, or lymphoma. In young patients (ages 15 to 40 years), multiple lytic and oval lesions in the same extremity are probably vascular tumors (hemangioendothelioma). In children younger than 5 years, multiple destructive lesions may represent metastatic disease such as neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans cell histiocytosis [LCH]) may also lead to multiple lesions in the young patient. Fibrous dysplasia and Paget disease may manifest with multiple lesions in all age groups.

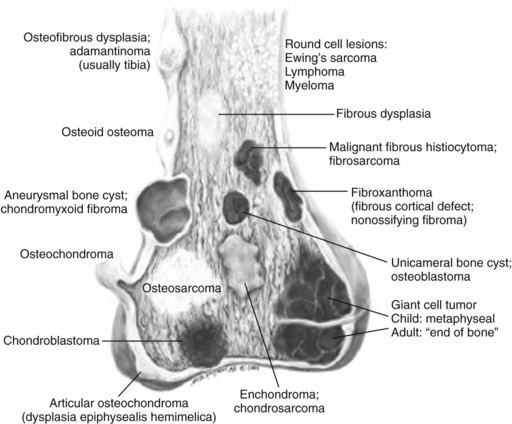

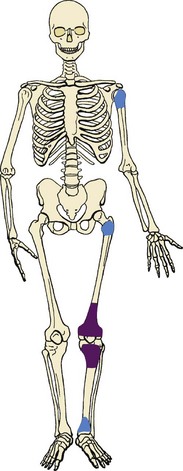

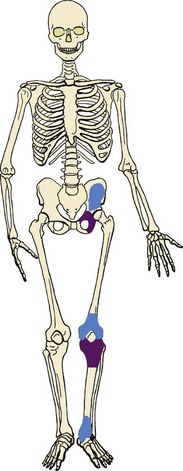

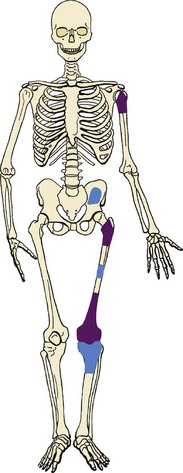

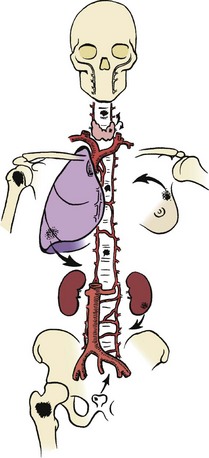

Anatomic location within bone: Certain lesions have a predilection for occurring within a certain bone or a particular part of the bone (Figure 9-1; Table 9-5).

Anatomic location within bone: Certain lesions have a predilection for occurring within a certain bone or a particular part of the bone (Figure 9-1; Table 9-5).

Table 9-5![]()

Most Common Musculoskeletal Tumors

| Tumor Type | Tumor Name |

| Soft tissue tumor (children) | Hemangioma |

| Soft tissue tumor (adults) | Lipoma |

| Malignant soft tissue tumor (children) | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Malignant soft tissue tumor (adults) | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma |

| Primary benign bone tumor | Osteochondroma |

| Primary malignant bone tumor | Osteosarcoma |

| Secondary benign lesion | Aneurysmal bone cyst |

| Secondary malignancies | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma Osteosarcoma Fibrosarcoma |

| Phalangeal tumor | Enchondroma |

| Sarcoma of the hand and wrist | Epithelioid sarcoma |

| Sarcoma of the foot and ankle | Synovial sarcoma |

Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia.

Typical neoplasms of whole bone:

Typical neoplasms of whole bone:

Tibia: adamantinoma, osteofibrous dysplasia

Tibia: adamantinoma, osteofibrous dysplasia

Posterior cortex distal femur: parosteal osteosarcoma, periosteal desmoid (also known as cortical desmoid, avulsive cortical irregularity)

Posterior cortex distal femur: parosteal osteosarcoma, periosteal desmoid (also known as cortical desmoid, avulsive cortical irregularity)

Typical neoplasms of part of bone (Table 9-6):

Typical neoplasms of part of bone (Table 9-6):

Table 9-6

Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia.

Epiphysis: giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteomyelitis (tuberculosis, fungus)

Epiphysis: giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, osteomyelitis (tuberculosis, fungus)

Giant cell tumor typically begins in the metaphysis and extends through the epiphysis to lie just below the cartilage.

Giant cell tumor typically begins in the metaphysis and extends through the epiphysis to lie just below the cartilage.

Metaphysis: metaphyseal fibrous defect (nonossifying fibroma), aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, osteosarcoma

Metaphysis: metaphyseal fibrous defect (nonossifying fibroma), aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, osteosarcoma

Diaphysis: Ewing sarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, eosinophilic granuloma (histiocytosis), multiple myeloma

Diaphysis: Ewing sarcoma, fibrous dysplasia, eosinophilic granuloma (histiocytosis), multiple myeloma

D Laboratory studies: Results of blood tests are often nonspecific. A set of routine studies should be obtained when the diagnosis is not obvious. Certain studies are appropriate for younger patients (up to age 40) and others for older patients (40 to 80 years; Box 9-1).

E Biopsy: Biopsy is generally performed after complete evaluation of the patient. It is of great benefit to both the pathologist and the surgeon to have a narrow working diagnosis because it allows accurate interpretation of the frozen-section analysis, and definitive treatment of some lesions can be based on the frozen section. Clinicians must follow several surgical principles:

1. The orientation and location of the biopsy tract are critical. If the lesion proves to be malignant, the entire biopsy tract must be removed with the underlying lesion. Transverse incisions should be avoided.

2. The surgeon must maintain meticulous hemostasis to prevent hematoma formation and subcutaneous hemorrhage. When possible, biopsy incisions are made through muscles so that the muscle layer can be closed tightly. Neurovascular structures should be avoided. Tourniquets are used to obtain tissue in a bloodless field and then are released so that bleeding points can be controlled. Avitene, Gelfoam, and Thrombostat sprays are used as necessary. If hemostasis cannot be achieved, a small drain should be placed at the corner of the wound to prevent hematoma formation. A compression dressing is routinely used on the extremities.

3. A frozen-section analysis is performed on all biopsy samples to ensure that adequate diagnostic tissue is obtained. Before biopsy, the surgeon should review the radiographs with the pathologist to plan the biopsy site. When possible, the soft tissue component rather than the bony component should be sampled.

4. All biopsy samples should be submitted for bacteriologic analysis if the frozen section does not reveal a neoplasm. Antibiotics should not be delivered until the cultures are obtained.

5. Needle biopsy is an excellent method for achieving a tissue diagnosis and providing minimum tissue disruption. Careful correlation of the small tissue sample with the radiographs often yields the correct diagnosis. When the nature of the lesion is obvious on the basis of the radiographic features and when adequate tissue can be obtained with a needle, the needle biopsy technique is safe to use. The pathologist must be experienced and comfortable with the small sample of tissue. When the diagnoses of needle biopsy and imaging studies are not concordant, an open biopsy should be performed to establish the diagnosis. Open biopsy is often necessary with low-grade tumors and when the needle biopsy does not provide a definitive diagnosis. Immunostains are helpful in diagnosis (Table 9-7).

Table 9-7

| Tumor | Immunostain |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | S100, +CD1A |

| Lymphoma | +CD20 |

| Ewing sarcoma | +CD99 |

| Chordoma | Keratin, S100 |

| Myeloma | +CD138 |

| Adamantinoma | Keratin |

Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Resident, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Virginia.

A Surgical procedures: The goal of the treatment of malignant bone tumors is to remove the lesion with minimal risk of local recurrence.

1. Limb salvage is performed when two essential criteria are met:

Local control of the lesion must be at least equal to that of amputation surgery.

Local control of the lesion must be at least equal to that of amputation surgery.

The limb that has been saved must be functional. A wide-margin surgical resection (excising a cuff of normal tissue around the tumor) is the operative goal.

The limb that has been saved must be functional. A wide-margin surgical resection (excising a cuff of normal tissue around the tumor) is the operative goal.

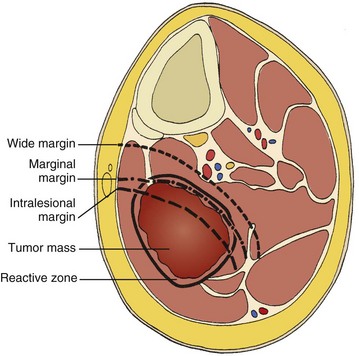

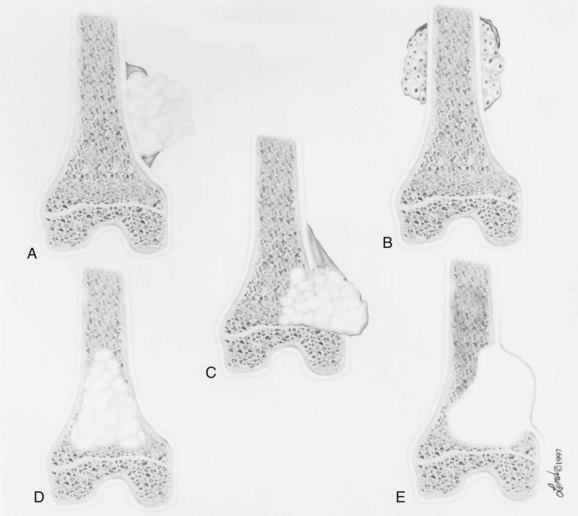

2. Surgical margins are graded according to the system of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (Figure 9-2).

Intralesional margin: The plane of dissection goes directly through the tumor. When the surgery involves malignant mesenchymal tumors, an intralesional margin results in 100% local recurrence.

Intralesional margin: The plane of dissection goes directly through the tumor. When the surgery involves malignant mesenchymal tumors, an intralesional margin results in 100% local recurrence.

Marginal margin: A marginal line of resection goes through the reactive zone of the tumor; the reactive zone contains inflammatory cells, edema, fibrous tissue, and satellites of tumor cells. When malignant mesenchymal tumors are resected, a plane of dissection through the reactive zone probably results in a local recurrence rate of 25% to 50%. A marginal margin may be safe and effective if the response to preoperative chemotherapy has been excellent (95% to 100% tumor necrosis).

Marginal margin: A marginal line of resection goes through the reactive zone of the tumor; the reactive zone contains inflammatory cells, edema, fibrous tissue, and satellites of tumor cells. When malignant mesenchymal tumors are resected, a plane of dissection through the reactive zone probably results in a local recurrence rate of 25% to 50%. A marginal margin may be safe and effective if the response to preoperative chemotherapy has been excellent (95% to 100% tumor necrosis).

Wide margin: A wide line of surgical resection is accomplished when the entire tumor is removed with a cuff of normal tissue. The local recurrence rate drops below 10% when such a surgical margin is achieved.

Wide margin: A wide line of surgical resection is accomplished when the entire tumor is removed with a cuff of normal tissue. The local recurrence rate drops below 10% when such a surgical margin is achieved.

Radical margin: A radical margin is achieved when the entire tumor and its compartment (all surrounding muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues) are removed.

Radical margin: A radical margin is achieved when the entire tumor and its compartment (all surrounding muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues) are removed.

Multiagent chemotherapy has a significant effect on both the efficacy of limb salvage and disease-free survival for osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing tumor.

Multiagent chemotherapy has a significant effect on both the efficacy of limb salvage and disease-free survival for osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing tumor.

The common mechanism of action of drugs is the induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The common mechanism of action of drugs is the induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

Most protocols entail preoperative regimens (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) for 8 to 24 weeks. The tumor is then restaged and, if appropriate, limb salvage is performed.

Most protocols entail preoperative regimens (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) for 8 to 24 weeks. The tumor is then restaged and, if appropriate, limb salvage is performed.

Patients undergo maintenance chemotherapy for 6 to 12 months.

Patients undergo maintenance chemotherapy for 6 to 12 months.

Patients with localized osteosarcoma or Ewing tumor have up to a 60% to 70% chance for long-term disease-free survival with the combination of multiagent chemotherapy and surgery.

Patients with localized osteosarcoma or Ewing tumor have up to a 60% to 70% chance for long-term disease-free survival with the combination of multiagent chemotherapy and surgery.

The role of chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma remains more controversial.

The role of chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma remains more controversial.

External beam irradiation is used in the following scenarios:

External beam irradiation is used in the following scenarios:

For local control of Ewing tumor, lymphoma, myeloma, and metastatic bone disease

For local control of Ewing tumor, lymphoma, myeloma, and metastatic bone disease

As an adjunct in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, in which it is used in combination with surgery.

As an adjunct in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, in which it is used in combination with surgery.

For their mechanism of action, which is the production of free radicals and direct genetic damage. There are several complications of radiation therapy:

For their mechanism of action, which is the production of free radicals and direct genetic damage. There are several complications of radiation therapy:

Postirradiation sarcoma: This is a devastating complication in which a spindle sarcoma occurs within the field of irradiation for a previous malignancy (e.g., Ewing tumor, breast cancer, Hodgkin disease). The histologic features are usually those of an osteosarcoma, a fibrosarcoma, or a malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Postirradiation sarcomas are probably more frequent in patients who undergo intensive chemotherapy (especially with alkylating agents) and irradiation.

Postirradiation sarcoma: This is a devastating complication in which a spindle sarcoma occurs within the field of irradiation for a previous malignancy (e.g., Ewing tumor, breast cancer, Hodgkin disease). The histologic features are usually those of an osteosarcoma, a fibrosarcoma, or a malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Postirradiation sarcomas are probably more frequent in patients who undergo intensive chemotherapy (especially with alkylating agents) and irradiation.

Late stress fractures: These also may occur in weight-bearing bones to which high-dose irradiation has been applied. The subtrochanteric region and the diaphysis of the femur are common sites.

Late stress fractures: These also may occur in weight-bearing bones to which high-dose irradiation has been applied. The subtrochanteric region and the diaphysis of the femur are common sites.

Several bone and soft tissue neoplasms have been associated with tumor suppressor genes or specific genetic defects. For osteosarcoma, the associations are the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene. For Ewing tumor, there is a balanced translocation of chromosomes 11 and 22. There is a gene fusion product from this balanced translocation: EWS-FLI1 (Table 9-8).

Table 9-8![]()

Common Tumor-Associated Genetic Translocations

| Tumor Type | Genetic Translocation |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | t(12;16) |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(11;22) |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;18) |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | t(9;22) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | t(1;13) or t(2;13) |

Courtesy of Luke S. Choi, MD, Fellow, Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital.

section 2 Soft Tissue Tumors

Soft tissue tumors are common. They may appear as small lumps or large masses.

A Classification: Soft tissue tumors can be broadly classified as benign or malignant (sarcoma) or characterized by reactive tumor-like conditions (Box 9-2). Lesions are classified according to the direction of differentiation of the lesion: the tumor tends to produce collagen (fibrous lesion), fat, or cartilage.

1. Benign soft tissue tumors: These tumors may occur in all age groups. The biologic behavior of these lesions varies from asymptomatic and self-limiting to growing and symptomatic. On occasion, benign lesions grow rapidly and invade adjacent tissues.

2. Malignant soft tissue tumors (sarcomas): Sarcomas are rare tumors of mesenchymal origin. In the United States, there are approximately 9000 new cases of soft tissue sarcoma each year.

Diagnosis: Patients often experience an enlarging painless or painful soft tissue mass, which is the most common reason for seeking medical attention.

Diagnosis: Patients often experience an enlarging painless or painful soft tissue mass, which is the most common reason for seeking medical attention.

Most sarcomas are large (>5 cm), deep, and firm.

Most sarcomas are large (>5 cm), deep, and firm.

In some instances, they are small and may be present for a long time before they are recognized as tumors (synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma).

In some instances, they are small and may be present for a long time before they are recognized as tumors (synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma).

Initial radiographic evaluation begins with radiographs in two planes.

Initial radiographic evaluation begins with radiographs in two planes.

MRI is the best imaging modality for defining the anatomy and helping characterize the lesion. When a mass is judged to be indeterminate, an open incisional or needle biopsy is performed. A definitive histologic diagnosis must be established before treatment is planned.

MRI is the best imaging modality for defining the anatomy and helping characterize the lesion. When a mass is judged to be indeterminate, an open incisional or needle biopsy is performed. A definitive histologic diagnosis must be established before treatment is planned.

CT scan of the chest is required in order to evaluate for metastasis. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for liposarcoma because of synchronous retroperitoneal liposarcoma.

CT scan of the chest is required in order to evaluate for metastasis. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained for liposarcoma because of synchronous retroperitoneal liposarcoma.

Treatment: Radiation therapy is an important adjunct to surgery in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas.

Treatment: Radiation therapy is an important adjunct to surgery in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas.

Ionizing radiation can be delivered preoperatively, perioperatively with brachytherapy after loading tubes, or postoperatively.

Ionizing radiation can be delivered preoperatively, perioperatively with brachytherapy after loading tubes, or postoperatively.

Treatment regimens are often designed to use combinations of the three types of preoperative, postoperative, and external beam irradiation. Poor prognostic factors include the presence of metastases, high grade, size greater than 5 cm, and location below the deep fascia.

Treatment regimens are often designed to use combinations of the three types of preoperative, postoperative, and external beam irradiation. Poor prognostic factors include the presence of metastases, high grade, size greater than 5 cm, and location below the deep fascia.

B Diagnosis: The evaluation of patients with soft tissue tumors must be systematic to avoid errors.

1. Unplanned removal of a soft tissue sarcoma is the most common error.

Residual tumor may exist at the site of the operative wound, and repeat excision for all patients with an unplanned removal should be performed.

Residual tumor may exist at the site of the operative wound, and repeat excision for all patients with an unplanned removal should be performed.

2. Delay in diagnosis may also occur if the clinician does not recognize that the lesion is malignant.

3. Patients who have a new soft tissue mass or one that is growing or causing pain should undergo MRI.

4. The MRI scan should be carefully reviewed with a radiologist to characterize the nature of the mass. If it can be determined that the lesion is a benign process such as a lipoma, ganglionic cyst, or muscle tear, then it is classified as a determinate lesion, and treatment can be planned without a biopsy. In contrast, if the exact nature of a lesion cannot be determined, the lesion is classified as indeterminate, and either a needle or open biopsy is necessary to determine the exact diagnosis. Then treatment can be planned.

5. Excisional biopsy should not be performed when the clinician does not know the origin of a soft tissue tumor.

C Metastasis: Most soft tissue sarcomas metastasize to the lung.

A Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma

1. Manifests as a slow-growing, painless mass in the hands and feet in children and young adults 3 to 30 years of age.

2. Radiographs may reveal a faint mass with stippling.

3. Histologic examination reveals a fibrous tumor with centrally located areas of calcification and cartilage formation.

4. After local excision, the tumor often recurs (in up to 50% of cases); however, the condition appears to resolve with maturity.

1. Palmar (Dupuytren) and plantar (Ledderhose) fibromatosis: These disorders consist of firm nodules of fibroblasts and collagen that develop in the palmar and plantar fascia. The nodules and fascia become hypertrophic, producing contractures.

2. Extraabdominal desmoid tumor

Most locally invasive of all benign soft tissue tumors.

Most locally invasive of all benign soft tissue tumors.

Commonly occurs in adolescents and young adults.

Commonly occurs in adolescents and young adults.

Patients with Gardner syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis) have colonic polyps and a 10,000-fold increased risk of developing desmoid tumors.

Patients with Gardner syndrome (familial adenomatous polyposis) have colonic polyps and a 10,000-fold increased risk of developing desmoid tumors.

On palpation, the tumor has a distinctive “rock-hard” character.

On palpation, the tumor has a distinctive “rock-hard” character.

Multiple lesions may be present in the same extremity (10% to 25%).

Multiple lesions may be present in the same extremity (10% to 25%).

Histologically, the tumor consists of well-differentiated fibroblasts and abundant collagen. The lesion infiltrates adjacent tissues. Immunohistochemistry study reveals positivity for estrogen receptor β, and inhibitors have been used for treatment.

Histologically, the tumor consists of well-differentiated fibroblasts and abundant collagen. The lesion infiltrates adjacent tissues. Immunohistochemistry study reveals positivity for estrogen receptor β, and inhibitors have been used for treatment.

Surgical treatment is aimed at resecting the tumor with a wide margin.

Surgical treatment is aimed at resecting the tumor with a wide margin.

Radiotherapy has been used as an adjunctive treatment to prevent recurrence and progression.

Radiotherapy has been used as an adjunctive treatment to prevent recurrence and progression.

Behavior of the tumor is capricious: Recurrent nodules may remain dormant for years or grow rapidly for some time and then stop growing.

Behavior of the tumor is capricious: Recurrent nodules may remain dormant for years or grow rapidly for some time and then stop growing.

1. A common reactive lesion that manifests as a painful, rapidly enlarging mass in a young person (15 to 35 years of age).

2. Half of these lesions occur in the upper extremity.

3. Short, irregular bundles and fascicles; a dense reticulum network; and only small amounts of mature collagen characterize the lesion histologically. Mitotic figures are common, but atypical mitoses are not a feature.

4. Treatment consists of excision with a marginal line of resection.

D Malignant fibrous soft tissue tumors: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma are the two malignant fibrous lesions.

Similar clinical and radiographic manifestations; treatment methods are similar

Similar clinical and radiographic manifestations; treatment methods are similar

Patients are generally between the ages of 30 and 80 years.

Patients are generally between the ages of 30 and 80 years.

Most common manifestation is an enlarging, generally painless mass.

Most common manifestation is an enlarging, generally painless mass.

MRI often shows a deep-seated, inhomogeneous mass that has a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images. The two lesions may be similar histologically, but there are distinctive features:

MRI often shows a deep-seated, inhomogeneous mass that has a low signal on T1-weighted images and a high signal on T2-weighted images. The two lesions may be similar histologically, but there are distinctive features:

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: The spindle and histiocytic cells are arranged in a storiform (cartwheel) pattern. Short fascicles of cells and fibrous tissue appear to radiate about a common center around slitlike vessels. Chronic inflammatory cells may also be present.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: The spindle and histiocytic cells are arranged in a storiform (cartwheel) pattern. Short fascicles of cells and fibrous tissue appear to radiate about a common center around slitlike vessels. Chronic inflammatory cells may also be present.

Fibrosarcoma: There is a fasciculated growth pattern, with fusiform or spindle-shaped cells, scanty cytoplasm, and indistinct borders, and the cells are separated by interwoven collagen fibers. In some cases, the tissue is organized into a herringbone pattern, which consists of intersecting fascicles in which the nuclei in one fascicle are viewed transversely but in an adjacent fascicle are viewed longitudinally.

Fibrosarcoma: There is a fasciculated growth pattern, with fusiform or spindle-shaped cells, scanty cytoplasm, and indistinct borders, and the cells are separated by interwoven collagen fibers. In some cases, the tissue is organized into a herringbone pattern, which consists of intersecting fascicles in which the nuclei in one fascicle are viewed transversely but in an adjacent fascicle are viewed longitudinally.

Treatment is by wide-margin local excision. Radiation therapy is employed in many cases when the size of the tumor exceeds 5 cm.

Treatment is by wide-margin local excision. Radiation therapy is employed in many cases when the size of the tumor exceeds 5 cm.

A common scenario is to deliver radiation preoperatively (5000 cGy), followed by resection of the lesion. A final radiation boost (1400 to 2000 cGy) is then administered postoperatively or with brachytherapy afterloading tubes if the margins are very close or positive.

A common scenario is to deliver radiation preoperatively (5000 cGy), followed by resection of the lesion. A final radiation boost (1400 to 2000 cGy) is then administered postoperatively or with brachytherapy afterloading tubes if the margins are very close or positive.

Postoperative external beam irradiation (6300 to 6600 cGy) yields equal local control rates, with a lower postoperative wound complication rate but a higher incidence of postoperative fibrosis.

Postoperative external beam irradiation (6300 to 6600 cGy) yields equal local control rates, with a lower postoperative wound complication rate but a higher incidence of postoperative fibrosis.

E Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

1. Rare, nodular, cutaneous tumor that occurs in early to middle adulthood

2. Low grade, with a tendency to recur locally, but it only rarely metastasizes (often after repeated local recurrence)

3. In 40% of the cases, it occurs on the upper or lower extremities. The tumor grows slowly but progressively.

4. The central portion of the nodules shows uniform fibroblasts arranged in a storiform pattern around an inconspicuous vasculature.

5. Wide-margin surgical resection is the best form of treatment.

A Lipomas: common benign tumors of mature fat

1. Occur in a subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intermuscular location

2. History of a mass is long, but sometimes the mass was only recently discovered.

4. Radiographs may show a radiolucent lesion in the soft tissues if the lipoma is deep within the muscle or between the muscle and bone.

5. CT scan or MRI shows a well-demarcated lesion with the same signal characteristics as those of mature fat on all sequences. On fat suppression sequences, the lipoma has a uniformly low signal. If the patient experiences no symptoms and the radiographic features are diagnostic of lipoma, no treatment is necessary.

6. If the mass is growing or causing symptoms, excision with a marginal line of resection or an intralesional margin is all that is necessary.

7. Local recurrence is uncommon.

Commonly occurs in men (45 to 65 years of age)

Commonly occurs in men (45 to 65 years of age)

Manifests as a solitary, painless, growing, firm nodule

Manifests as a solitary, painless, growing, firm nodule

Histologically characterized by a mixture of mature fat cells and spindle cells. There is a mucoid matrix with a varying number of birefringent collagen fibers.

Histologically characterized by a mixture of mature fat cells and spindle cells. There is a mucoid matrix with a varying number of birefringent collagen fibers.

1. Type of sarcoma; direction of differentiation is toward fatty tissue

2. Heterogeneous group of tumors, having in common the presence of lipoblasts (signet ring–shaped cells) in the tissue

3. Liposarcomas virtually never occur in the subcutaneous tissues.

4. They are classified into the following types:

Well-differentiated liposarcoma (low grade)

Well-differentiated liposarcoma (low grade)

Myxoid liposarcoma (intermediate grade)

Myxoid liposarcoma (intermediate grade)

5. Liposarcomas metastasize according to the grade of the lesion:

A Neurilemoma (benign schwannoma)

2. Occurs in young to middle-aged adults (20 to 50 years of age)

3. Patients have no symptoms except for the presence of the mass.

4. Tumor grows slowly and may wax and wane in size (cystic changes).

5. MRI studies may demonstrate an eccentric mass arising from a peripheral nerve, or they may show only an indeterminate soft tissue mass (low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images).

6. Histologically, the lesion is composed of Antoni A and B areas.

Compact spindle cells usually having twisted nuclei; indistinct cytoplasm; and occasionally clear, intranuclear vacuoles

Compact spindle cells usually having twisted nuclei; indistinct cytoplasm; and occasionally clear, intranuclear vacuoles

There may be nuclear palisading, whorling of cells, and Verocay bodies.

There may be nuclear palisading, whorling of cells, and Verocay bodies.

When the lesion is predominantly cellular (Antoni A), the tumor may be confused with a sarcoma.

When the lesion is predominantly cellular (Antoni A), the tumor may be confused with a sarcoma.

Treatment: removing the eccentric mass while leaving the nerve intact

Treatment: removing the eccentric mass while leaving the nerve intact

1. Solitary or multiple (neurofibromatosis)

2. Superficial, slow-growing, and painless

3. When they involve a major nerve, they may expand it in a fusiform manner.

4. Histologic study shows interlacing bundles of elongated cells with wavy, dark-staining nuclei.

5. Cells are associated with wirelike strands of collagen.

6. Small to moderate amounts of mucoid material separate the cells and collagen

C Neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease)

1. Autosomal dominant trait (both peripheral and central forms)

2. Café au lait spots (smooth) and Lisch nodules (melanocytic hamartomas in the iris)

3. Variable skeletal abnormalities (metaphyseal fibrous defect [nonossifying fibroma], scoliosis, and long-bone bowing)

4. Malignant changes occur in 5% to 30% of affected patients.

5. Pain and an enlarging soft tissue mass may herald conversion to a sarcoma.

1. Manifests as a small nodule or a large extremity mass

1. The most common sarcoma in young patients; may grow rapidly

2. Composed of spindle cells in parallel bundles, multinucleated giant cells, and racquet-shaped cells

3. Cross-striations within the tumor cells (rhabdomyoblasts)

4. Rhabdomyosarcomas are sensitive to multiagent chemotherapy and wide-margin surgical resection after induction of chemotherapy. External beam irradiation plays a prominent role in treatment.

1. Commonly seen in children and adults

2. Cutaneous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular location

3. Large tumors have signs of vascular engorgement (aching, heaviness, swelling).

4. MRI scans demonstrate a heterogeneous lesion with numerous small blood vessels and fatty infiltration.

5. It is important to examine the patient in both the supine and standing positions. (The lower extremity often fills with blood after several minutes).

6. Radiographs may reveal small phleboliths.

7. Nonoperative treatment: NSAIDs, vascular stockings, and activity modification if local measures adequately control discomfort

8. Can be treated by application of a sclerosing agent such as alcohol

1. Out-pouching of the synovial lining of an adjacent joint

2. Common locations include the wrist, foot, and knee.

3. Filled with gelatinous, mucoid material

4. Paucicellular connective tissue without a true epithelial lining

5. MRI: homogeneously low signal on T1-weighted images and a very bright signal on T2-weighted images; contrast agent such as gadolinium is useful in differentiating a cyst from a solid neoplasm because cysts do not enhance (except for a small rim at the periphery) but active neoplasms usually do.

B Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)

1. Reactive condition (not a true neoplasm) characterized by an exuberant proliferation of synovial villi and nodules

2. May occur locally (within a joint) or diffusely

3. The knee is affected most often, followed in frequency by the hip and shoulder.

4. Manifests with pain and swelling in the affected joint

5. Recurrent, atraumatic hemarthrosis is the hallmark (arthrocentesis demonstrates a bloody effusion).

6. Cystic erosions may occur on both sides of the joint.

7. Highly vascular villi are lined with plump, hyperplastic synovial cells; hemosiderin-stained, multinucleated giant cells; and chronic inflammatory cells.

8. Treatment is aimed at complete synovectomy by arthroscopy for resection of all the intraarticular disease, followed by open posterior synovectomy to remove the posterior extraarticular extension.

9. Local recurrence is common (30% to 50% of cases) despite complete synovectomy.

10. External beam irradiation (3500 to 4000 cGy) can reduce the rate of local recurrence to 10% to 20%.

C Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath

1. Benign nodular tumor occurs along the tendon sheaths (hands/feet).

2. Moderately cellular (sheets of rounded or polygonal cells) zones; hypocellular, collagenized zones; multinucleated giant cells are common, as are xanthoma cells.

3. Treatment: resection with a marginal margin

4. Local recurrence is common (usually treated with repeat excision).

1. Synovial proliferative disorder that occurs within joints or bursae, ranging in appearance from metaplasia of the synovial tissue to firm nodules of cartilage

2. Typically affects young adults, who present with pain, stiffness, and swelling

3. The knee is the most common location.

4. Radiographs may demonstrate fine, stippled calcification.

1. Highly malignant, high-grade tumor that occurs near joints, most commonly around the knee

2. Although the name implies that it arises from synovial cells, it rarely arises from an intraarticular location.

3. May be present for years or may manifest as a rapidly enlarging mass

4. Lymph nodes may be involved.

5. Most common synovial sarcoma is in the foot.

6. Radiographs or CT scans may show mineralization within the lesion in up to 25% of cases (spotty mineralization may even resemble the peripheral mineralization seen in heterotopic ossification).

7. The tumor is often biphasic, with both epithelial and spindle cell components.

The epithelial component may show epithelial cells that form glands or nests, or they may line cystlike spaces.

The epithelial component may show epithelial cells that form glands or nests, or they may line cystlike spaces.

9. The tumor may also be composed of a single type of cell (monophasic); the monophasic fibrous type is much more common than the monophasic epithelial type.

10. Translocation between chromosome 18 and the X chromosome—t(X;18)—is always present in tumor cells, and staining of the tumor cells yields positive results for keratin and epithelial membrane antigen.

11. The balanced translocation results in gene fusion products. The two most common are SYT-SSX1 and SYT-SSX2.

12. Wide-margin surgical resection with adjuvant radiotherapy is the most common method of treatment.

13. Metastases develop in 30% to 60% of cases.

14. Larger tumors (>5 to 10 cm) are more prone to distant spread.

1. Rare nodular tumor that commonly occurs in the upper extremities of young adults

2. May also occur about the buttock/thigh, knee, and foot

3. The most common sarcoma of the hand

4. May ulcerate and mimic a granuloma or rheumatoid nodule

5. Lymph node metastases are common.

6. Cells range in shape from ovoid to polygonal, with deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm (cellular pleomorphism is minimal).

7. Often misdiagnosed as benign processes.

8. Wide-margin surgical resection is necessary to prevent local recurrence.

1. Manifests as a slow-growing mass in association with tendons or aponeuroses

2. Usually occurs about the foot and ankle but may also involve the knee, thigh, and hand

3. Characterized by compact nests or fascicles of rounded or fusiform cells with clear cytoplasm; multinucleated giant cells are common

4. Wide-margin surgical resection with adjuvant irradiation is the treatment of choice.

1. Manifests as a slow-growing, painless mass in young adults (15 to 35 years of age)

2. Occurs in the anterior thigh

3. Dense, fibrous trabeculae dividing the tumor into an organoid or nestlike arrangement; cells are large and rounded and contain one or more vesicular nuclei with small nucleoli

4. Treatment: wide-margin surgical resection with adjuvant irradiation in selected cases

1. Hematoma may occur after trauma to the extremity.

2. Organizes and resolves with time

3. Sarcomas may spontaneously hemorrhage into the body of the tumor or after minor trauma and masquerade as a benign process. A lack of fascial plane tracking and subcutaneous ecchymosis suggests that the bleeding is contained by a pseudocapsule; this is an important physical examination finding.

4. Clinicians should monitor patients with hematomas at 6-week intervals until the mass resolves.

5. MRI scanning is often not able to distinguish a simple hematoma from a sarcoma with spontaneous hemorrhage.

B Myositis ossificans (heterotopic ossification)

1. Develops after single or repetitive episodes of trauma (occasionally, patients cannot recall the traumatic episode)

2. Most common locations are over the diaphyseal segment of long bones (in the middle aspect of the muscle bellies).

3. As maturation progresses, radiographs show peripheral mineralization with a central lucent area.

4. Lesion is not attached to the underlying bone, but in some cases, it may become fixed to the periosteal surface.

5. Zonal pattern, with mature, trabecular bone at the periphery and immature tissue in the center

6. Nonoperative treatment is all the management that is necessary.

section 3 Bone Tumors

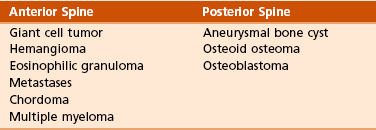

A common classification system for bone tumors is shown in Table 9-9.

Table 9-9

Classification of Primary Tumors of Bone*

*Classification is based on that advocated by Lichtenstein L: Classification of primary tumors of bone, Cancer 4:335-341, 1951.

1. Malignant neoplasms of connective tissue (mesenchymal) origin

2. Exhibit rapid growth in a centripetal manner and invade adjacent normal tissues

3. Each year in the United States, about 2800 new bone sarcomas are diagnosed.

Malignant bone tumors manifest most commonly with pain. This is in contrast to soft tissue tumors, which most commonly manifest as a painless mass.

Malignant bone tumors manifest most commonly with pain. This is in contrast to soft tissue tumors, which most commonly manifest as a painless mass.

4. High-grade, malignant bone tumors tend to destroy the overlying cortex and spread into the soft tissues.

5. Low-grade tumors are generally contained within the cortex or the surrounding periosteal rim.

6. Bone sarcomas metastasize primarily via the hematogenous route; the lungs are the most common site.

7. Osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma may also metastasize to other bone sites either at the initial manifestation or later in the disease.

Self-limiting benign bone lesion produces pain in young patients (5 to 30 years of age)

Pain that increases with time, pain at night

Pain that increases with time, pain at night

Pain may be referred to an adjacent joint, and when the lesion is intracapsular, it may simulate arthritis.

Pain may be referred to an adjacent joint, and when the lesion is intracapsular, it may simulate arthritis.

May produce painful nonstructural scoliosis, growth disturbances, and flexion contractures

May produce painful nonstructural scoliosis, growth disturbances, and flexion contractures

Scoliosis caused by an osteoid osteoma results in a curve with the lesion on the concave side. This is thought to result fromj marked paravertebral muscle spasm.

Scoliosis caused by an osteoid osteoma results in a curve with the lesion on the concave side. This is thought to result fromj marked paravertebral muscle spasm.

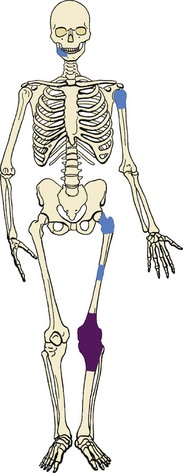

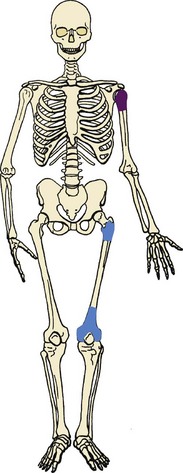

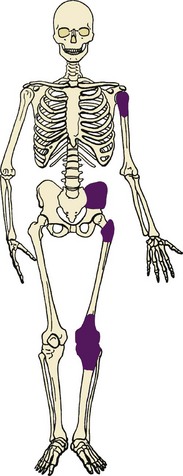

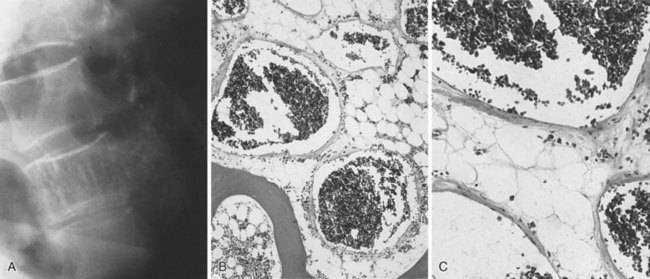

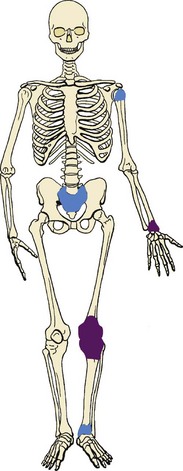

Common locations include the proximal femur, tibial diaphysis, and spine (Figure 9-3).

Common locations include the proximal femur, tibial diaphysis, and spine (Figure 9-3).

Radiographs usually show intensely reactive bone and a radiolucent nidus (Figure 9-4). It may be possible to detect the lesion only with tomograms, CT scans, or MRI scans, because of the intense sclerosis.

Radiographs usually show intensely reactive bone and a radiolucent nidus (Figure 9-4). It may be possible to detect the lesion only with tomograms, CT scans, or MRI scans, because of the intense sclerosis.

The nidus is, by definition, always less than 1.5 cm in diameter, although the area of reactive bone sclerosis may be long.

The nidus is, by definition, always less than 1.5 cm in diameter, although the area of reactive bone sclerosis may be long.

Technetium-labeled bone scans always yield positive findings and show intense focal uptake.

Technetium-labeled bone scans always yield positive findings and show intense focal uptake.

CT scans are superior to MRI scans in detecting and characterizing osteoid osteomas because the CT scans provide better contrast between the lucent nidus and the reactive bone than the MRI scan does.

CT scans are superior to MRI scans in detecting and characterizing osteoid osteomas because the CT scans provide better contrast between the lucent nidus and the reactive bone than the MRI scan does.

There is a distinct demarcation between the nidus and the reactive bone (nidus consists of an interlacing network of osteoid trabeculae with variable mineralization), trabecular organization is haphazard, and the greatest degree of mineralization is in the center of the lesion.

There is a distinct demarcation between the nidus and the reactive bone (nidus consists of an interlacing network of osteoid trabeculae with variable mineralization), trabecular organization is haphazard, and the greatest degree of mineralization is in the center of the lesion.

2. Patients can be treated with three different methods: NSAIDs, CT scan–guided radiofrequency ablation, and open surgical removal.

1. Rare bone-producing tumor that can attain a large size and is not self-limiting

2. Manifests with pain, and when the lesion involves the spine, neurologic symptoms may be present

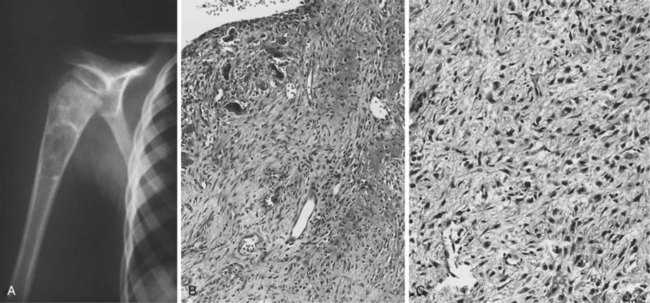

3. Common locations include the spine, proximal humerus, and hip (Figure 9-5).

4. Causes bone destruction, with or without the characteristic reactive bone formation in osteoid osteoma

5. Area of bone destruction occasionally has a moth-eaten or permeative appearance simulating a malignancy.

6. Lesions show regularly shaped nuclei containing little chromatin but abundant cytoplasm (tissue is loosely arranged, with numerous blood vessels).

7. Tumor does not permeate the normal trabecular bone but instead merges with it.

8. Treatment: curettage or excision with a marginal line of resection

1. Spindle cell neoplasms that produce osteoid are arbitrarily classified as osteosarcoma.

2. There are many types of osteosarcoma (Box 9-3 and Figure 9-6).

3. Lesions that must be recognized include high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma (ordinary or classic osteosarcoma), parosteal osteosarcoma, periosteal osteosarcoma, telangiectatic osteosarcoma, osteosarcoma occurring with Paget disease, and osteosarcoma after irradiation.

4. Historically, osteosarcoma was treated by amputation; long-term studies demonstrated a survival rate of only 10% to 20%, the pulmonary system being the most common site of failure.

5. Multiagent chemotherapy has dramatically improved long-term survival and the potential for limb salvage.

Doxorubicin (cardiac toxicity)

Doxorubicin (cardiac toxicity)

Methotrexate (for cases of myelosuppression, also administer leucovorin)

Methotrexate (for cases of myelosuppression, also administer leucovorin)

6. Chemotherapy both kills the micrometastases that are present in 80% to 90% of the patients at presentation and sterilizes the reactive zone around the tumor.

7. Preoperative chemotherapy is delivered for 8 to 12 weeks, followed by resection of the tumor.

8. Rate of long-term survival is approximately 60% to 70%.

9. Prognostic factors that adversely affect survival include (1) expression of P-glycoprotein, high serum level of alkaline phosphatase, high lactic dehydrogenase level, vascular invasion, and no alteration of DNA ploidy after chemotherapy and (2) the absence of anti–shock protein-90 antibodies after chemotherapy.

10. Osteosarcoma is associated with an abnormality in the tumor suppressor genes Rb (retinoblastoma) and p53 (Li-Fraumeni syndrome).

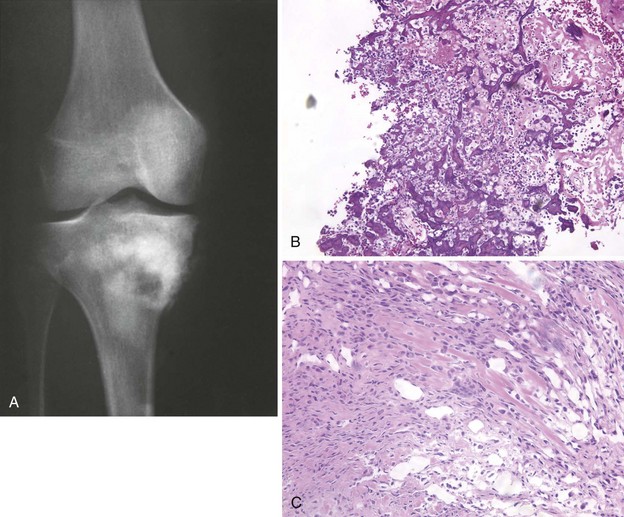

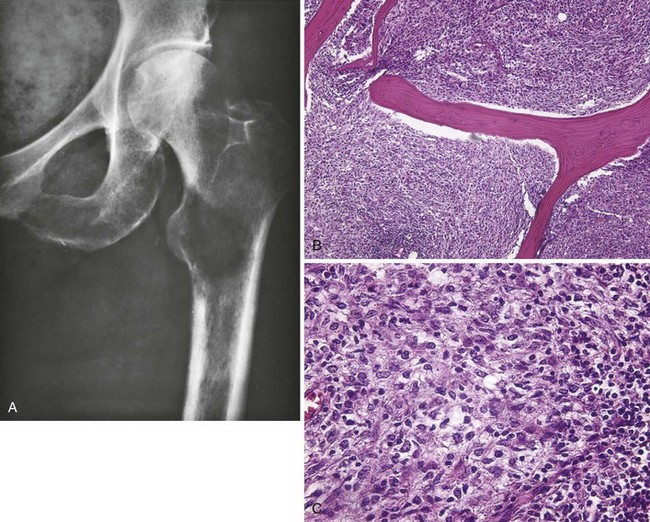

High-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma

High-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma

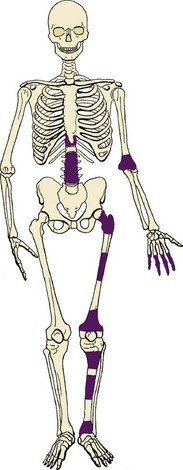

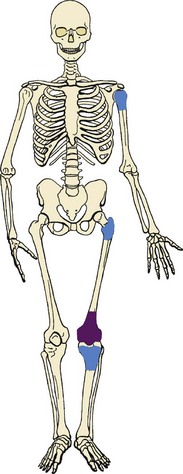

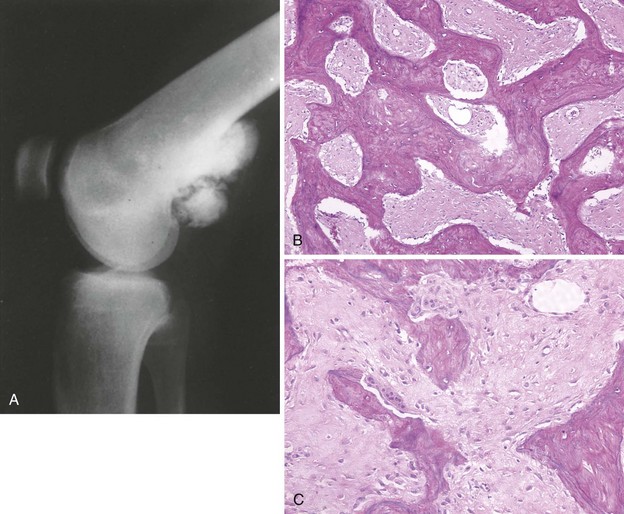

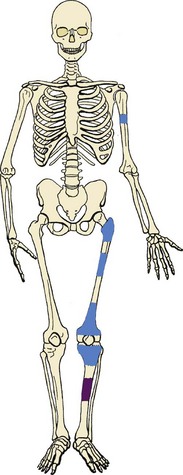

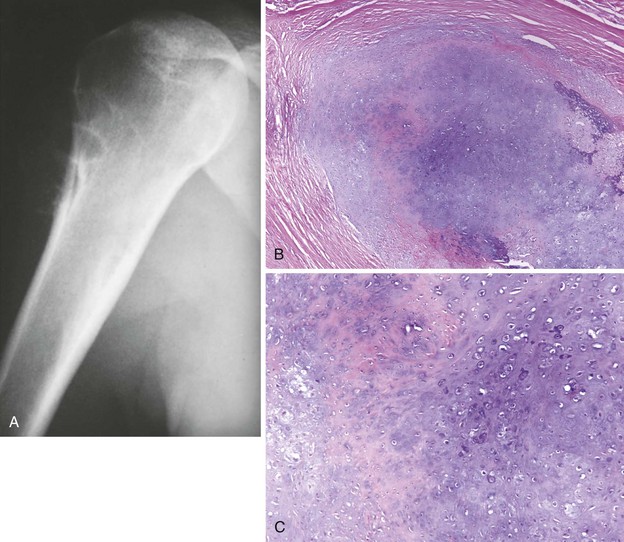

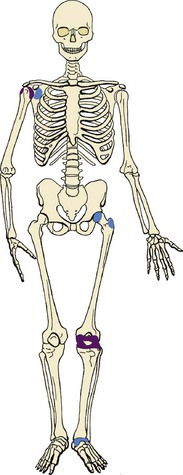

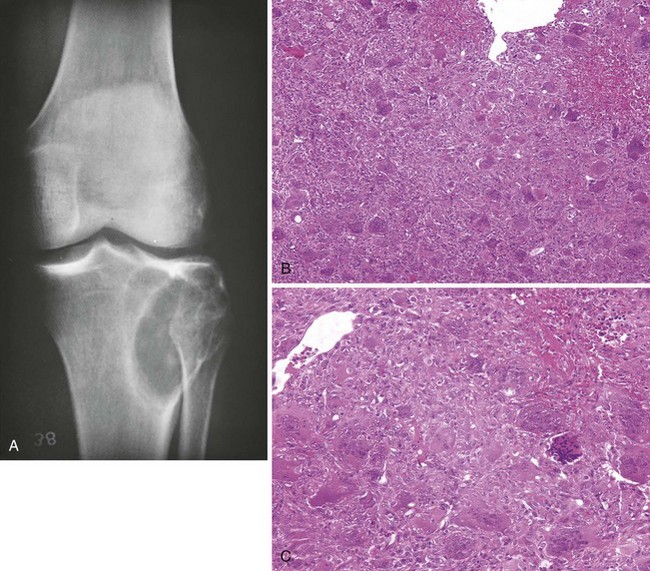

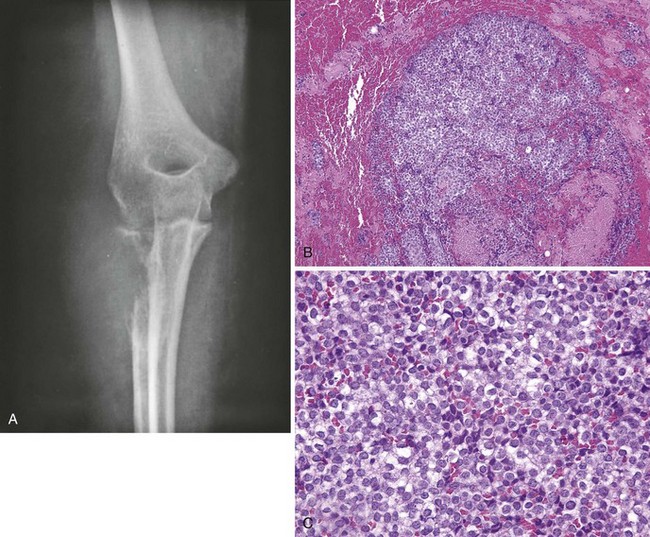

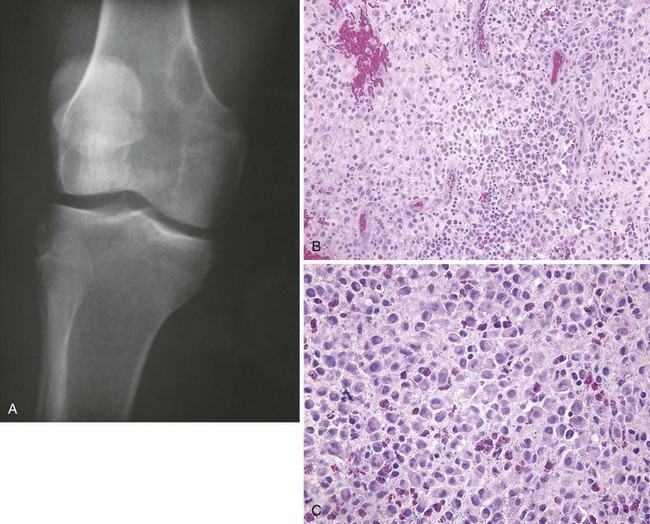

Also called “ordinary” or “classic” osteosarcoma, this neoplasm is the most common type of osteosarcoma and usually occurs about the knee in children and young adults (Figure 9-7), but its incidence has a second peak in late adulthood.

Also called “ordinary” or “classic” osteosarcoma, this neoplasm is the most common type of osteosarcoma and usually occurs about the knee in children and young adults (Figure 9-7), but its incidence has a second peak in late adulthood.

Other common sites include the proximal humerus, proximal femur, and pelvis.

Other common sites include the proximal humerus, proximal femur, and pelvis.

Patients present primarily with pain.

Patients present primarily with pain.

More than 90% of intramedullary osteosarcomas are high-grade and penetrate the cortex early to form a soft tissue mass (stage IIB lesion).

More than 90% of intramedullary osteosarcomas are high-grade and penetrate the cortex early to form a soft tissue mass (stage IIB lesion).

About 10% to 20% of affected patients have pulmonary metastases at presentation.

About 10% to 20% of affected patients have pulmonary metastases at presentation.

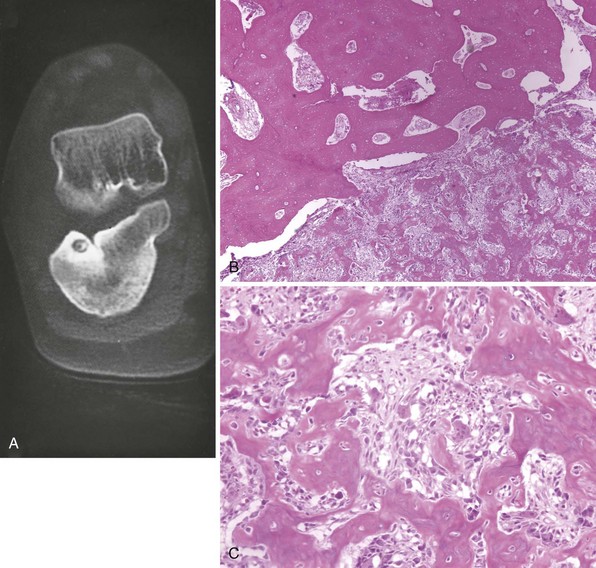

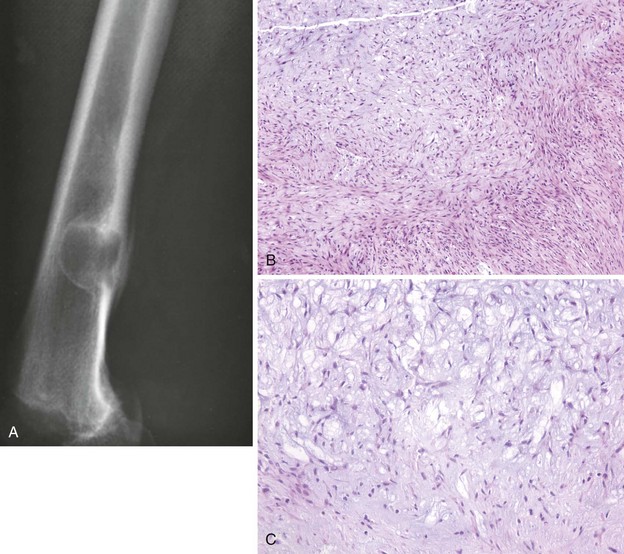

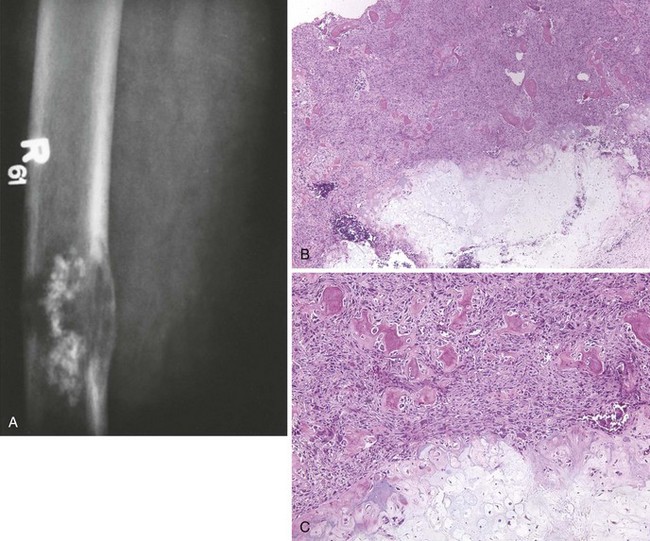

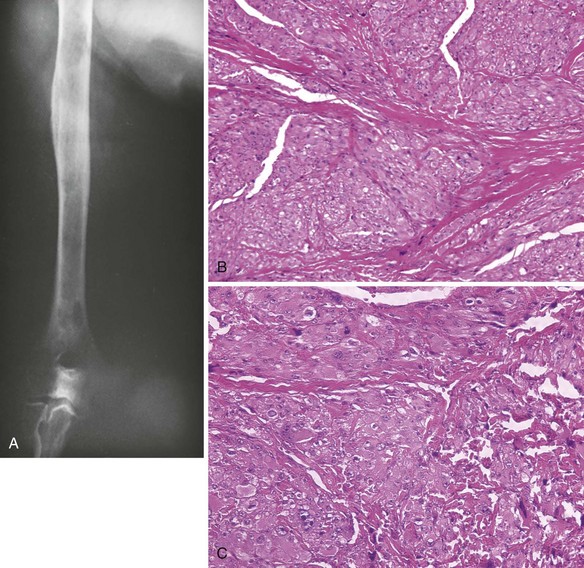

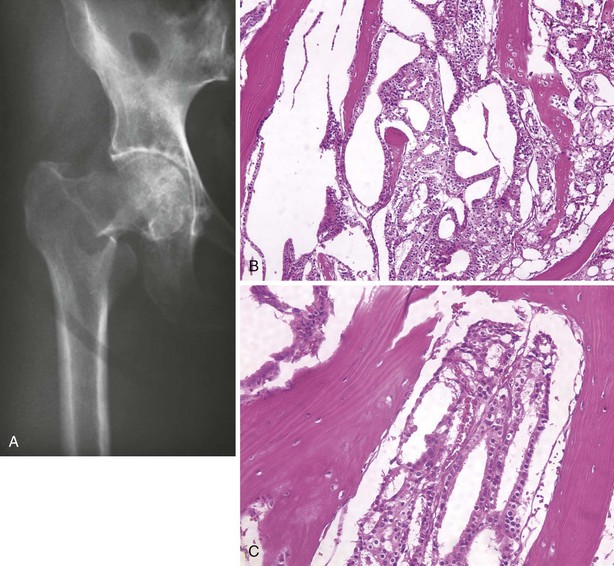

Radiographs demonstrate a lesion in which there is bone destruction and bone formation (Figure 9-8). On occasion, the lesion is purely sclerotic or lytic. MRI and CT scans are useful for defining the anatomy of the lesion with regard to intramedullary extension, involvement of neurovascular structures, and muscle invasion.

Radiographs demonstrate a lesion in which there is bone destruction and bone formation (Figure 9-8). On occasion, the lesion is purely sclerotic or lytic. MRI and CT scans are useful for defining the anatomy of the lesion with regard to intramedullary extension, involvement of neurovascular structures, and muscle invasion.

Diagnosis depends on two histologic criteria: (1) the tumor cells produce osteoid and (2) the stromal cells are frankly malignant.

Diagnosis depends on two histologic criteria: (1) the tumor cells produce osteoid and (2) the stromal cells are frankly malignant.

Treatment: neoadjuvant chemotherapy (i.e., before surgery), followed by wide-margin surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (i.e., after surgery)

Treatment: neoadjuvant chemotherapy (i.e., before surgery), followed by wide-margin surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy (i.e., after surgery)

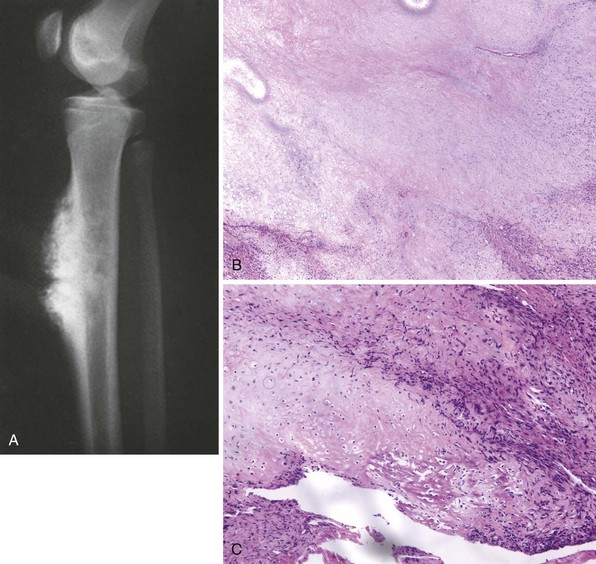

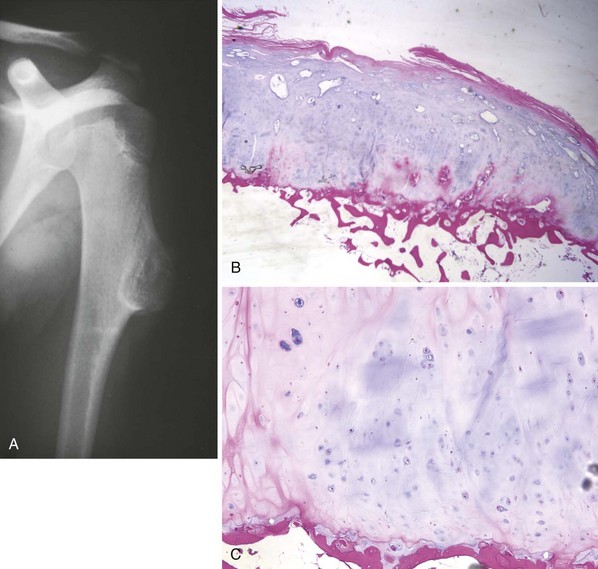

Low-grade osteosarcoma that occurs on the surface of the metaphysis of long bones

Low-grade osteosarcoma that occurs on the surface of the metaphysis of long bones

Affected patients often present with a painless mass.

Affected patients often present with a painless mass.

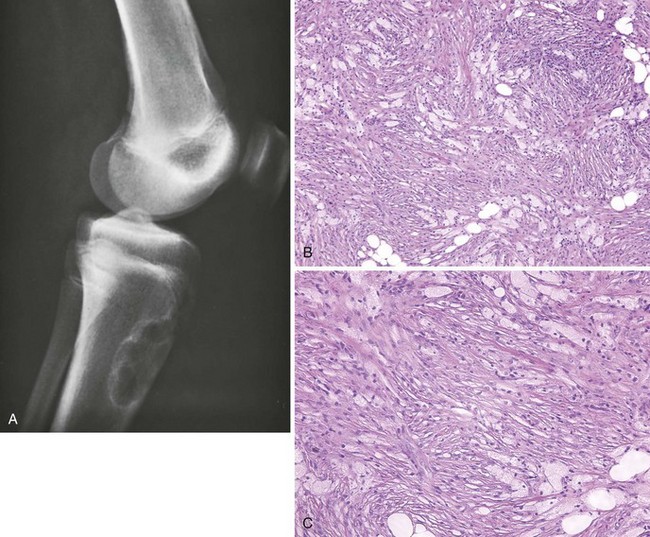

Most common sites are the posterior aspect of the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-9).

Most common sites are the posterior aspect of the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-9).

Characteristic radiographic appearance: a heavily ossified, often lobulated mass arising from the cortex (Figure 9-10)

Characteristic radiographic appearance: a heavily ossified, often lobulated mass arising from the cortex (Figure 9-10)

Most prominent feature is regularly arranged osseous trabeculae; between the nearly normal trabeculae are slightly atypical spindle cells, which typically invade skeletal muscle found at the periphery of the tumor.

Most prominent feature is regularly arranged osseous trabeculae; between the nearly normal trabeculae are slightly atypical spindle cells, which typically invade skeletal muscle found at the periphery of the tumor.

Treatment: resection with a wide margin, which is usually curative

Treatment: resection with a wide margin, which is usually curative

Of the lesions that appear radiographically to be parosteal osteosarcoma, approximately 17% are high-grade malignancies (dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma).

Of the lesions that appear radiographically to be parosteal osteosarcoma, approximately 17% are high-grade malignancies (dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma).

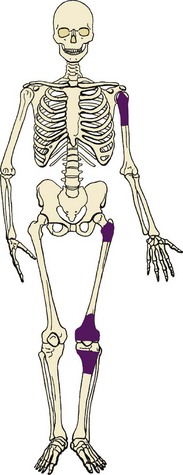

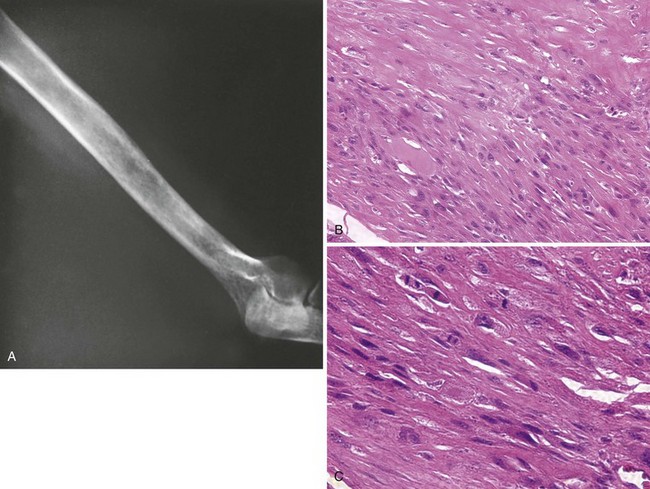

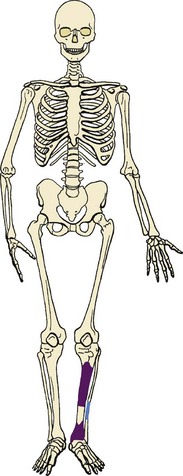

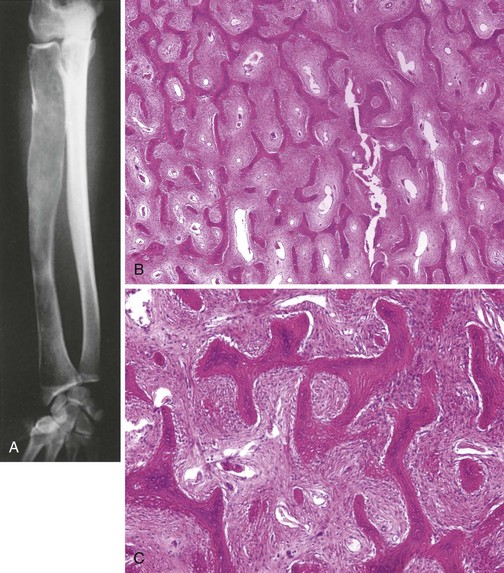

Rare surface form of osteosarcoma occurs most often in the diaphysis of long bones (typically the femur or tibia; Figure 9-11).

Rare surface form of osteosarcoma occurs most often in the diaphysis of long bones (typically the femur or tibia; Figure 9-11).

Radiographic appearance is fairly constant: a sunburst-type lesion rests on a saucerized cortical depression (Figure 9-12).

Radiographic appearance is fairly constant: a sunburst-type lesion rests on a saucerized cortical depression (Figure 9-12).

Histologic characteristics: The lesion is predominantly chondroblastic, and the grade of the lesion is intermediate (grade II). Highly anaplastic regions are not found.

Histologic characteristics: The lesion is predominantly chondroblastic, and the grade of the lesion is intermediate (grade II). Highly anaplastic regions are not found.

The prognosis for periosteal osteosarcoma is intermediate between those of very low-grade parosteal osteosarcoma and high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma. Preoperative chemotherapy, resection, and maintenance chemotherapy constitute the preferred treatment. The risk of pulmonary metastasis is 10% to 15%.

The prognosis for periosteal osteosarcoma is intermediate between those of very low-grade parosteal osteosarcoma and high-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma. Preoperative chemotherapy, resection, and maintenance chemotherapy constitute the preferred treatment. The risk of pulmonary metastasis is 10% to 15%.

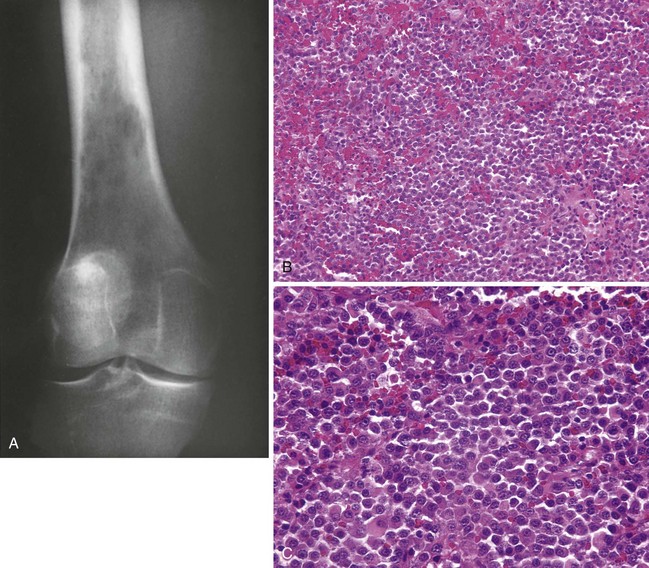

The tissue of the lesion can be described as a bag of blood with few cellular elements.

The tissue of the lesion can be described as a bag of blood with few cellular elements.

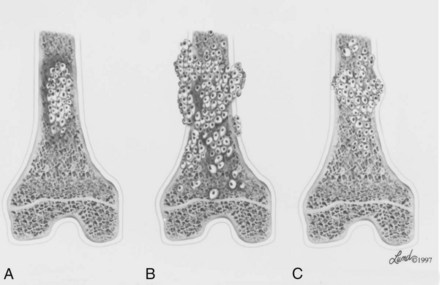

The radiographic features of telangiectatic osteosarcoma are those of a destructive, lytic, expansile lesion. Telangiectatic osteosarcomas occur in the same locations as aneurysmal bone cysts (Figure 9-13), and the radiographic appearances of both can be confused.

The radiographic features of telangiectatic osteosarcoma are those of a destructive, lytic, expansile lesion. Telangiectatic osteosarcomas occur in the same locations as aneurysmal bone cysts (Figure 9-13), and the radiographic appearances of both can be confused.

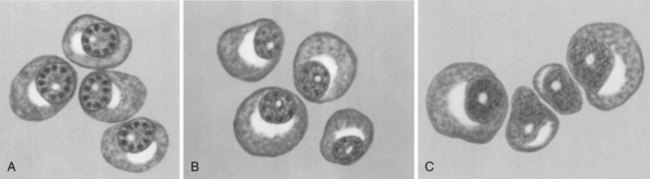

Appearances of these lesions are shown in Figure 9-14.

1. Histologic and radiographic features

When benign cartilage tumors occur on the surface of the bone, they are called periosteal chondroma

When benign cartilage tumors occur on the surface of the bone, they are called periosteal chondroma

They occur on the surfaces of the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal femur (Figure 9-15).

They occur on the surfaces of the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal femur (Figure 9-15).

Appearance: usually a well-demarcated, shallow cortical defect and a slight periosteal chondroma

Appearance: usually a well-demarcated, shallow cortical defect and a slight periosteal chondroma

Buttress of cortical bone at the edges of the lesion

Buttress of cortical bone at the edges of the lesion

One third of the periosteal chondromas exhibit a mineralized cartilaginous matrix on the radiograph (Figure 9-16), whereas two thirds have no apparent radiographic mineralization.

One third of the periosteal chondromas exhibit a mineralized cartilaginous matrix on the radiograph (Figure 9-16), whereas two thirds have no apparent radiographic mineralization.

In the medullary cavity in the metaphysis of long bones, especially the proximal femur and humerus and the distal femur, they are called enchondromas (Figure 9-17).

In the medullary cavity in the metaphysis of long bones, especially the proximal femur and humerus and the distal femur, they are called enchondromas (Figure 9-17).

Enchondromas are also common in the hand, where they usually occur in the diaphysis and metaphysis. Lesions in the hand may be hypercellular and display worrisome histologic features, and pathologic fractures in the hand are common.

Enchondromas are also common in the hand, where they usually occur in the diaphysis and metaphysis. Lesions in the hand may be hypercellular and display worrisome histologic features, and pathologic fractures in the hand are common.

Most enchondromas in long bones are asymptomatic.

Most enchondromas in long bones are asymptomatic.

Radiographically there may be a prominent stippled or mottled calcified appearance (Figure 9-18).

Radiographically there may be a prominent stippled or mottled calcified appearance (Figure 9-18).

Tumor is composed of small cells that lie in lacunar spaces; it is hypocellular, and the cells have a bland appearance (no pleomorphism, anaplasia, or hyperchromasia).

Tumor is composed of small cells that lie in lacunar spaces; it is hypocellular, and the cells have a bland appearance (no pleomorphism, anaplasia, or hyperchromasia).

When lesions are not causing pain, serial radiographs are obtained to ensure that the lesions are inactive (not growing). Radiographs are obtained every 3 to 6 months for 1 to 2 years and then annually as necessary.

When lesions are not causing pain, serial radiographs are obtained to ensure that the lesions are inactive (not growing). Radiographs are obtained every 3 to 6 months for 1 to 2 years and then annually as necessary.

Enchondroma can be distinguished from low-grade chondrosarcoma on serial plain radiographs. (10)In low-grade chondrosarcomas, cortical bone changes (large erosions [>50%] of the cortex, cortical thickening, and destruction) or lysis of the previously mineralized cartilage is visible.

Enchondroma can be distinguished from low-grade chondrosarcoma on serial plain radiographs. (10)In low-grade chondrosarcomas, cortical bone changes (large erosions [>50%] of the cortex, cortical thickening, and destruction) or lysis of the previously mineralized cartilage is visible.

2. Ollier disease/Maffucci syndrome

When there are many lesions, the involved bones are dysplastic, and the lesions tend toward unilaterality, the diagnosis is multiple enchondromatosis, or Ollier disease.

When there are many lesions, the involved bones are dysplastic, and the lesions tend toward unilaterality, the diagnosis is multiple enchondromatosis, or Ollier disease.

Inheritance pattern is sporadic.

Inheritance pattern is sporadic.

If soft tissue angiomas are also present, the diagnosis is Maffucci syndrome.

If soft tissue angiomas are also present, the diagnosis is Maffucci syndrome.

Patients with multiple enchondromatosis are at increased risk of malignancy (in Ollier disease, 30%; in Maffucci syndrome, 100%).

Patients with multiple enchondromatosis are at increased risk of malignancy (in Ollier disease, 30%; in Maffucci syndrome, 100%).

Patients with Maffucci syndrome also have a markedly increased risk of visceral malignancies, such as astrocytomas and gastrointestinal malignancies.

Patients with Maffucci syndrome also have a markedly increased risk of visceral malignancies, such as astrocytomas and gastrointestinal malignancies.

For most enchondromas, no treatment other than observation is required. When surgical treatment is necessary, enchondromas are treated by curettage and bone grafting. Periosteal chondromas are usually excised with a marginal margin.

For most enchondromas, no treatment other than observation is required. When surgical treatment is necessary, enchondromas are treated by curettage and bone grafting. Periosteal chondromas are usually excised with a marginal margin.

Benign surface lesions probably arise secondary to aberrant cartilage (from the perichondrial ring) on the surface of bone.

Benign surface lesions probably arise secondary to aberrant cartilage (from the perichondrial ring) on the surface of bone.

They manifest with a painless mass after trauma, or the mass is discovered incidentally.

They manifest with a painless mass after trauma, or the mass is discovered incidentally.

Osteochondromas usually occur about the knee, proximal femur, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-19).

Osteochondromas usually occur about the knee, proximal femur, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-19).

Characteristic appearance: a surface lesion in which the cortex of the lesion and the underlying cortex are continuous and the medullary cavity of the host bone also flows into (is continuous with) the osteochondroma (Figure 9-20).

Characteristic appearance: a surface lesion in which the cortex of the lesion and the underlying cortex are continuous and the medullary cavity of the host bone also flows into (is continuous with) the osteochondroma (Figure 9-20).

Osteochondromas may have a narrow stalk (pedunculated) or a broad base (sessile).

Osteochondromas may have a narrow stalk (pedunculated) or a broad base (sessile).

They typically occur at the site of tendon insertions, and the affected bone is abnormally wide.

They typically occur at the site of tendon insertions, and the affected bone is abnormally wide.

Underlying cortex is covered by a thin cap of cartilage (usually only 2 to 3 mm thick;. in a growing child, the cap thickness may exceed 1 to 2 cm).

Underlying cortex is covered by a thin cap of cartilage (usually only 2 to 3 mm thick;. in a growing child, the cap thickness may exceed 1 to 2 cm).

Chondrocytes are arranged in linear clusters, with an appearance resembling that of the normal physis.

Chondrocytes are arranged in linear clusters, with an appearance resembling that of the normal physis.

When asymptomatic, these lesions are treated with observation only.

When asymptomatic, these lesions are treated with observation only.

Patients may experience pain secondary to muscle irritation, mechanical trauma (contusions), or an inflamed bursa over the lesion. In this scenario, excision is a logical alternative.

Patients may experience pain secondary to muscle irritation, mechanical trauma (contusions), or an inflamed bursa over the lesion. In this scenario, excision is a logical alternative.

Pain in the absence of mechanical factors is a warning sign of malignant change.

Pain in the absence of mechanical factors is a warning sign of malignant change.

The development of a sarcoma in an osteochondroma is rare, occurring in far fewer than 1% of cases.

The development of a sarcoma in an osteochondroma is rare, occurring in far fewer than 1% of cases.

Destruction of the subchondral bone, mineralization of a soft tissue mass, and an inhomogeneous appearance are radiographic changes of malignant transformation.

Destruction of the subchondral bone, mineralization of a soft tissue mass, and an inhomogeneous appearance are radiographic changes of malignant transformation.

A low-grade chondrosarcoma is usually present, although a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma may occur in rare cases.

A low-grade chondrosarcoma is usually present, although a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma may occur in rare cases.

The lesion is termed a “secondary chondrosarcoma.”

The lesion is termed a “secondary chondrosarcoma.”

The prognosis is usually excellent; these low-grade tumors seldom metastasize.

The prognosis is usually excellent; these low-grade tumors seldom metastasize.

3. Multiple hereditary exostoses

The osteochondromas are often sessile and large. This is an autosomal dominant condition with mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 gene loci. Approximately 10% of patients with multiple exostoses develop a secondary chondrosarcoma. The EXT1 mutation is associated with a greater burden of disease and higher risk of malignancy.

The osteochondromas are often sessile and large. This is an autosomal dominant condition with mutations in the EXT1 and EXT2 gene loci. Approximately 10% of patients with multiple exostoses develop a secondary chondrosarcoma. The EXT1 mutation is associated with a greater burden of disease and higher risk of malignancy.

1. Centered in the epiphysis in young patients, usually with open physes

2. The most common locations are the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-21).

3. Lesion is usually in the epiphysis; it may also occur in an apophysis.

4. Manifests with pain referable to the involved joint.

5. It causes a central region of bone destruction that is usually sharply demarcated from the normal medullary cavity by a thin rim of sclerotic bone (Figure 9-22).

6. Mineralization may or may not occur within the lesion.

7. The basic proliferating cells are thought to be chondroblasts.

Scattered multinucleated giant cells are found throughout the lesion.

Scattered multinucleated giant cells are found throughout the lesion.

8. Treatment: curettage (intralesional margin) and bone grafting

1. Rare, benign cartilage tumors that contain variable amounts of chondroid, fibromatoid, and myxoid elements

2. More common in boys and men

3. Tend to involve long bones (especially the tibia); the pelvis and distal femur are other common locations (Figure 9-23)

4. Manifest with pain of variable duration (months to years).

5. There is a lytic, destructive lesion that is eccentric and sharply demarcated from the adjacent normal bone (Figure 9-24).

6. It grows in lobules, and there is often a condensation of cells at the periphery of the lobules (concentration of chondroid element may vary from light to heavy).

1. Intramedullary chondrosarcoma

This malignant neoplasm of cartilage occurs in older adults.

This malignant neoplasm of cartilage occurs in older adults.

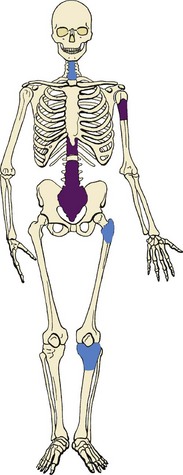

Most common locations include the shoulder and pelvic girdles, knee, and spine.

Most common locations include the shoulder and pelvic girdles, knee, and spine.

Patients may have pain or a mass.

Patients may have pain or a mass.

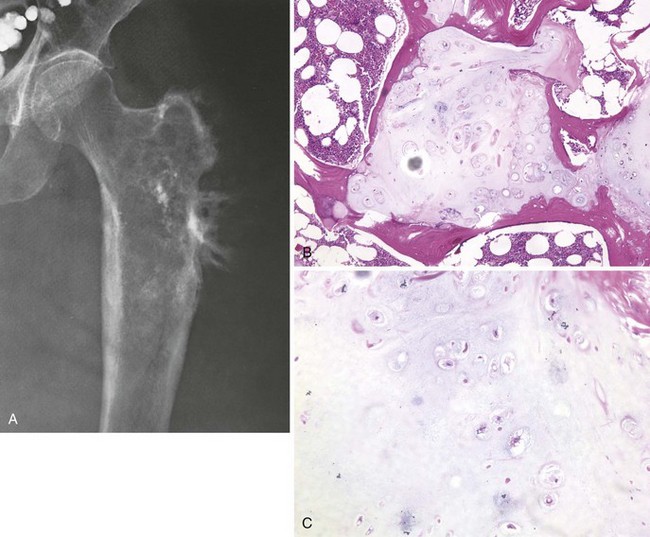

Radiographs usually show diagnostic findings, with bone destruction, thickening of the cortex, and mineralization consistent with cartilage within the lesion (Figure 9-25).

Radiographs usually show diagnostic findings, with bone destruction, thickening of the cortex, and mineralization consistent with cartilage within the lesion (Figure 9-25).

Prominent cortical changes are present in 85% of affected patients.

Prominent cortical changes are present in 85% of affected patients.

Differentiating malignant cartilage may be extremely difficult on the basis of histologic features alone.

Differentiating malignant cartilage may be extremely difficult on the basis of histologic features alone.

The clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of a particular lesion must be considered in combination to avoid incorrect diagnosis. The criteria for the diagnosis of malignancy include the following:

The clinical, radiographic, and histologic features of a particular lesion must be considered in combination to avoid incorrect diagnosis. The criteria for the diagnosis of malignancy include the following:

More than an occasional cell with two such nuclei

More than an occasional cell with two such nuclei

Especially large cartilage cells with large single or multiple nuclei containing clumps of chromatin

Especially large cartilage cells with large single or multiple nuclei containing clumps of chromatin

Chondromas of the hand (enchondromas)—the lesions in patients with Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome—and periosteal chondromas may have atypical histopathologic features (Figure 9-26).

Chondromas of the hand (enchondromas)—the lesions in patients with Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome—and periosteal chondromas may have atypical histopathologic features (Figure 9-26).

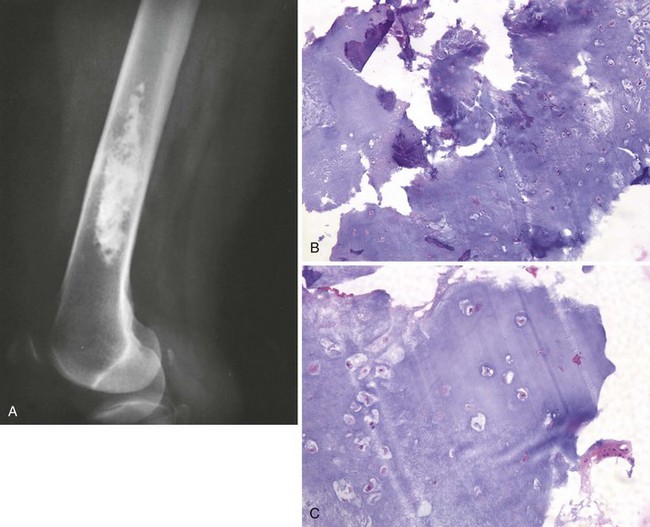

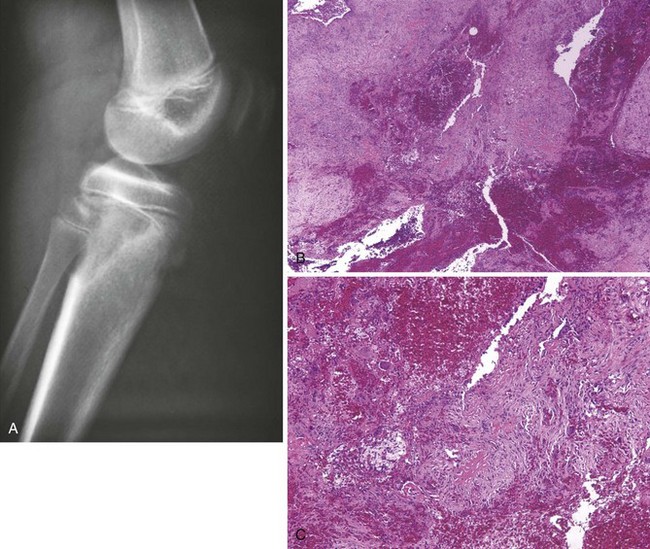

2. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma

Most malignant cartilage tumor

Most malignant cartilage tumor

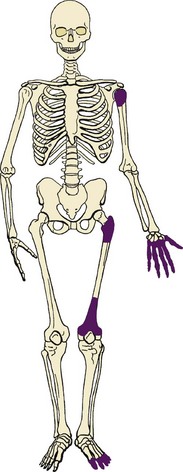

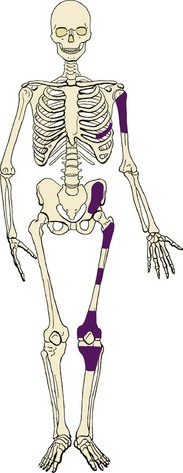

Most common locations include the distal and proximal femur and the proximal humerus (Figure 9-27).

Most common locations include the distal and proximal femur and the proximal humerus (Figure 9-27).

Bimorphic histologic and radiographic appearances

Bimorphic histologic and radiographic appearances

Low-grade cartilage component that is intimately associated with a high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma)

Low-grade cartilage component that is intimately associated with a high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma)

More than 80% of the lesions are typical chondrosarcomas with a superimposed, highly destructive area (Figure 9-28).

More than 80% of the lesions are typical chondrosarcomas with a superimposed, highly destructive area (Figure 9-28).

Manifestations are similar to those of low-grade chondrosarcoma, including pain and decreased function.

Manifestations are similar to those of low-grade chondrosarcoma, including pain and decreased function.

Prognosis is poor, and rate of long-term survival is less than 10%.

Prognosis is poor, and rate of long-term survival is less than 10%.

Treatment: wide-margin surgical resection and multiagent chemotherapy

Treatment: wide-margin surgical resection and multiagent chemotherapy

A Metaphyseal fibrous defect (also known as nonossifying fibroma, nonosteogenic fibroma, and xanthoma)

2. Most such lesions resolve spontaneously and are probably not true neoplasms.

3. Most common locations are the distal femur, distal tibia, and proximal tibia.

4. These lesions are usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally.

5. Characteristic radiographic appearance: a lucent lesion that is metaphyseal, eccentric, and surrounded by a sclerotic rim (Figure 9-29). The overlying cortex may be slightly expanded and thinned.

6. Cellular, fibroblastic connective tissue background, with the cells arranged in whorled bundles (numerous giant cells, lipophages, and various amounts of hemosiderin pigmentation).

7. Treatment: observation if the radiographic appearance is characteristic and the risk of pathologic fracture is not excessive.

8. If more than 50% to 75% of the cortex is involved and the patient has symptoms, curettage and bone grafting are performed.

1. Rare and low-grade but aggressive fibrous tumor of bone

3. When process is low grade, residual or reactive trabeculated (or corrugated) bone is often present.

4. Lesion is composed of abundant collagen and mature fibroblasts with no cellular atypia.

5. With wide-margin surgical resection, the risk of local recurrence is lowest, but the joint must be removed in young patients.

1. Presentation and localization are similar to those of osteosarcoma.

2. This tumor affects primarily older persons but does occur during all decades of life.

3. Lytic bone destruction is often in permeative pattern (Figure 9-30).

4. Spindle cells, variable collagen production, and a herringbone pattern

V MALIGNANT FIBROUS HISTIOCYTOMA

A Most common locations include the distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal femur, ilium, and proximal humerus (Figure 9-31).

B Malignant bone tumors that have proliferating cells with a histiocytic quality

C Nuclei are often indented, the cytoplasm is usually abundant and may be slightly foamy, the nucleoli are often large, and multinucleated giant cells are usually a prominent feature.

D Variable amounts of fibrous tissue found within the lesion, and the fibrogenic areas have a storiform appearance

E Patients present with pain and swelling.

F This lesion is destructive, with either purely lytic bone destruction or a mixed pattern of bone destruction and formation (Figure 9-32).

A Chordoma is a malignant neoplasm in which the cell of origin is derived from primitive notochordal tissue.

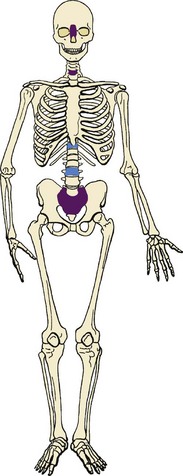

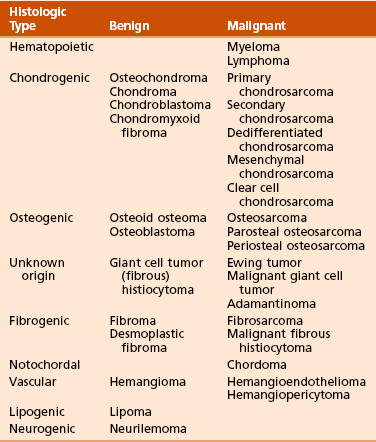

B Occurs predominantly at the ends of the vertebral column (sacrococcygeal; Figure 9-33)

C About 10% of chordomas occur in the vertebral bodies (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions).

D Patients present with an insidious onset of pain. Lesions in the sacrum may manifest as pelvic pain, low-back pain, or hip pain or with primarily gastrointestinal symptoms (obstipation, constipation, loss of rectal tone). When vertebral bodies are involved, neurologic symptoms may vary widely because of nerve compression.

E Radiographs often do not reveal the true extent of sacrococcygeal chordomas. The sacrum is difficult to evaluate on plain radiographs because of overlying bowel gas and fecal material and the angulation of the sacrum away from the x-ray beam on the anteroposterior view. In addition, the anteroposterior pelvic view reveals bone destruction only at the sacral cortical margins and neural foramina; these areas are not typically involved early.

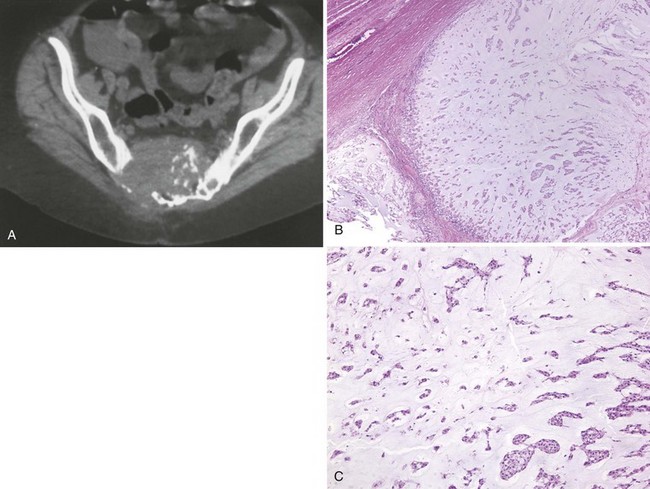

F CT scans show midline bone destruction and a soft tissue mass (Figure 9-34).

G MRI is an excellent modality for both detecting a chordoma and defining the anatomic features of the tumor.

1. Low signal on T1-weighted images

2. Very bright signal on T2-weighted images

3. Sacrum is often expanded, and the soft tissue mass may exhibit irregular mineralization.

4. In the vertebral bodies, areas of lytic bone destruction or a mixed pattern of both bone formation and bone destruction are often observed.

H The tumor grows in distinct lobules.

1. Chordoma cells sometimes have a vacuolated appearance and are called physaliferous cells.

2. Often arrayed in strands in a mass of mucus

3. Treatment: wide-margin surgical resection

4. Radiation therapy may be added if a wide margin is not achieved.

J Chordomas metastasize late in the course of the disease, and local extension can be fatal.

1. These tumors usually occur in vertebral bodies.

2. Patients may present with pain or pathologic fracture (often asymptomatic).

3. Vertebral hemangiomas have a characteristic appearance, with lytic destruction and vertical striations or a coarsened honeycomb appearance. On occasion, more than one bone is involved.

4. There are numerous blood channels. Most lesions are cavernous, although some may be a mixture of capillary and cavernous blood spaces.

1. May occur in any age group, and affected patients present with pain

2. Multifocal involvement of the bones of the same extremity is common

3. Predominantly oval lytic lesion with no reactive bone formation

4. The tumor cells form vascular spaces. The lesions range in structure from very well differentiated (easily recognizable vascular spaces) to very undifferentiated (difficult to recognize their vasoformative quality).

5. Low-grade multifocal lesions may be treated with radiation alone.

1. Lymphoma of bone is uncommon and occurs in three scenarios:

As a solitary focus (primary lymphoma of bone)

As a solitary focus (primary lymphoma of bone)

In association with other osseous sites and nonosseous sites (nodal disease and soft tissue masses)

In association with other osseous sites and nonosseous sites (nodal disease and soft tissue masses)

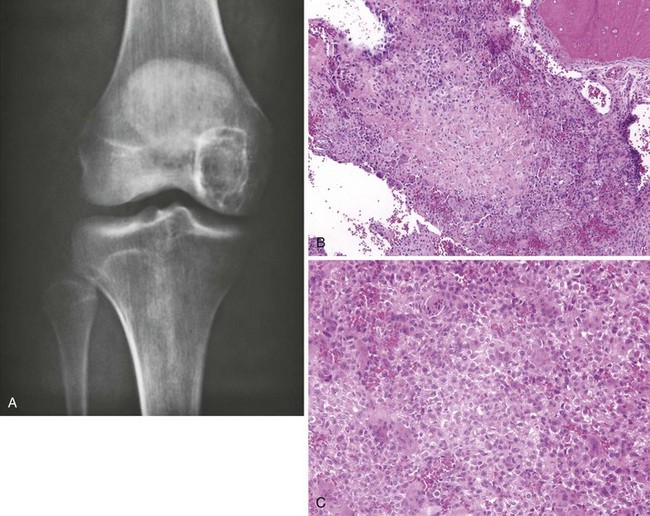

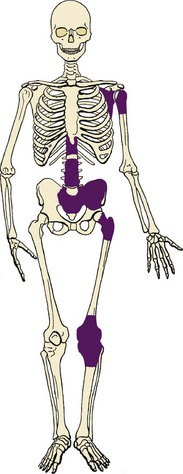

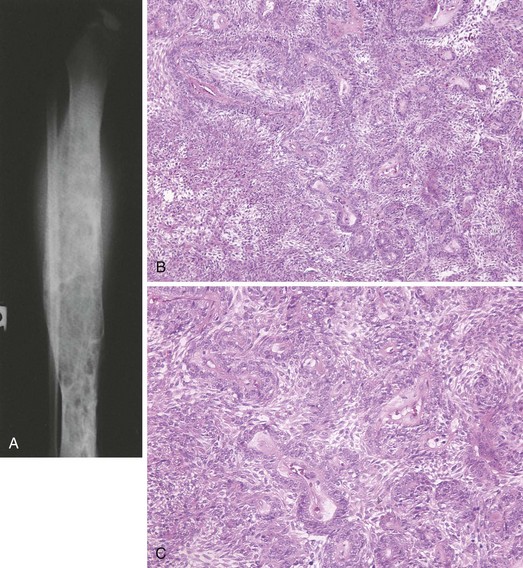

2. The most common locations include the distal femur, proximal tibia, pelvis, proximal femur, vertebra, and shoulder girdle (Figure 9-36).

4. Affected patients generally present with pain.

5. Images often show a lesion that involves a large portion of the bone (long lesion; Figure 9-37).

Bone destruction is common and often has a mottled appearance.

Bone destruction is common and often has a mottled appearance.

Reactive bone formation admixed with bone destruction is often observed. The cortex may be thickened.

Reactive bone formation admixed with bone destruction is often observed. The cortex may be thickened.

6. A mixed cellular infiltrate is usually present. Most lymphomas of bone are diffuse, large B-cell lymphomas.

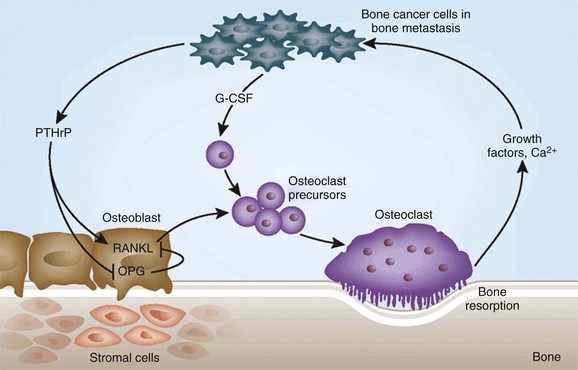

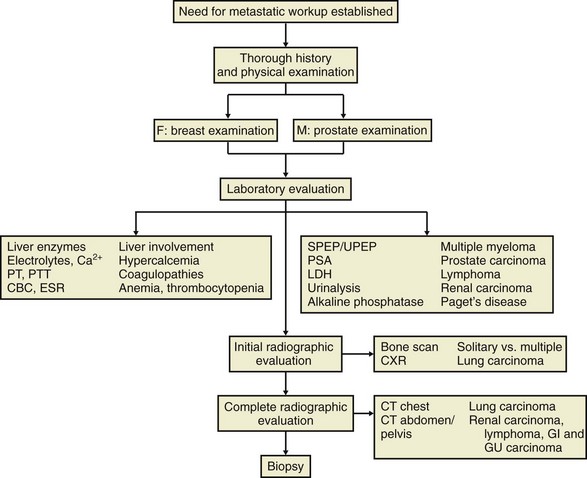

7. Treatment generally combines multiagent chemotherapy and consolidative irradiation.