1

Orbit

Trauma

Blunt Trauma

Orbital Contusion

Periocular bruising caused by blunt trauma; often with injury to the globe, paranasal sinuses, and bony socket; traumatic optic neuropathy or orbital hemorrhage may be present. Patients report pain and may have decreased vision. Signs include lid edema and ecchymosis, and ptosis. Isolated contusion is a preseptal (eyelid) injury and typically resolves without sequelae. Traumatic ptosis secondary to levator muscle contusion may take up to 3 months to resolve; most oculoplastic surgeons observe for 6 months prior to surgical repair.

• When the globe is intact and vision unaffected, ice compresses can be used every hour for 20 minutes during the first 48 hours to decrease swelling.

• Concomitant injuries should be treated accordingly.

Orbital Hemorrhage / Orbital Compartment Syndrome

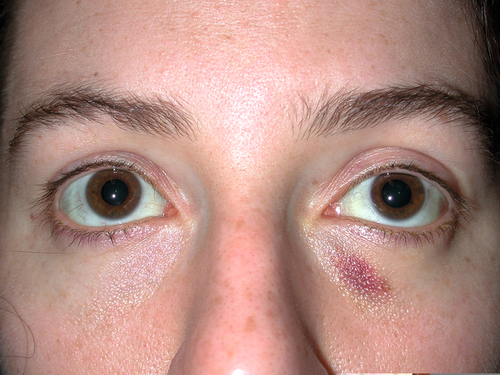

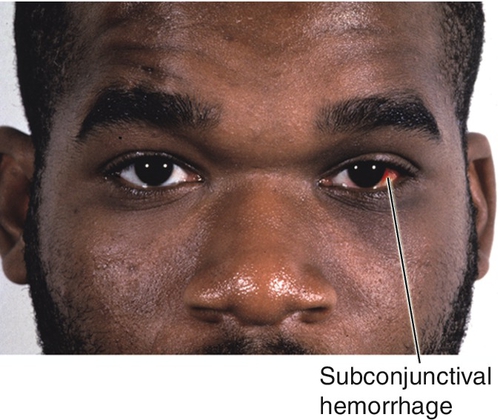

Accumulation of blood throughout the intraorbital tissues due to surgery or trauma (retrobulbar hemorrhage) may cause proptosis, distortion of the globe, and optic nerve stretching and compression (orbital compartment syndrome). Patients may report pain and decreased vision. Signs include bullous, subconjunctival hemorrhage, tense orbit, proptosis, resistance to retropulsion of globe, limitation of ocular movements, lid ecchymosis, and increased intraocular pressure. Immediate recognition and treatment is critical in determining outcome. Urgent treatment measures may include canthotomy and cantholysis. Evacuation of focal hematomas or bony decompression is reserved for the most severe cases with an associated optic neuropathy.

Orbital Fractures

Fracture of the orbital walls may occur in isolation (e.g., blow-out fracture) or with displaced or nondisplaced orbital-rim fractures. There may be concomitant ocular, optic nerve, maxillary, mandibular, or intracranial injuries.

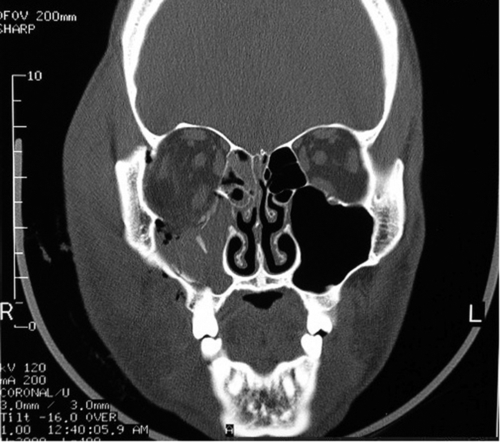

Orbital floor (blow-out) fracture

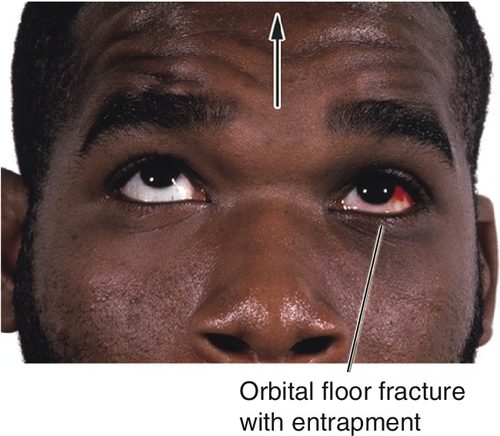

This is the most common orbital fracture requiring repair and usually involves the maxillary bone in the posterior medial floor (weakest point), and may extend laterally to the infraorbital canal. Orbital contents may prolapse or become entrapped in maxillary sinus. Signs and symptoms include diplopia on upgaze (anterior fracture) or downgaze (posterior fracture), enophthalmos, globe ptosis, and infraorbital nerve hypesthesia. Orbital and lid emphysema is often present and may become extensive with nose blowing.

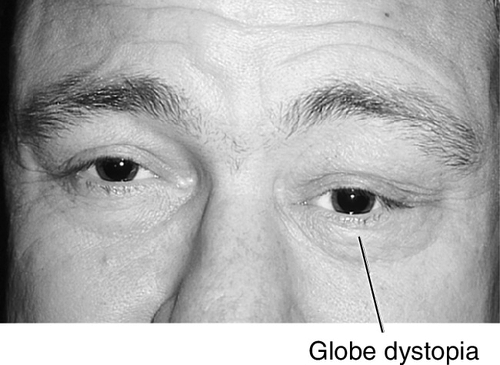

Figure 1-3 Orbital floor blow-out fracture with enophthalmos and globe dystopia and ptosis of the left eye.

Figure 1-4 Same patient as Figure 1-3 demonstrating entrapment of the left inferior rectus and inability to look up.

• For mild trauma, orbital CT scan need not be obtained in the absence of orbital signs.

• Orbital surgery consultation should be considered especially in the setting of diplopia, large floor fractures (> 50% of orbital floor surface area), trismus, facial asymmetry, inferior rectus entrapment, and enophthalmos. Consider surgical repair after 1 week to allow for reduction of swelling, except in cases of pediatric trapdoor-type fractures with extraocular muscle entrapment where emergent repair is advocated.

Pediatric floor fracture

This differs significantly from an adult fracture because the bones are pliable rather than brittle. A “trapdoor” phenomenon is created where the inferior rectus muscle or perimuscular tissue can be entrapped in the fracture site. In this case, enophthalmos is unlikely, but ocular motility is limited dramatically. The globe halts abruptly with ductions opposite the entrapped muscle (most often on upgaze with inferior rectus involvement) as if it is “tethered.” Forced ductions are positive; nausea and bradycardia (oculocardiac reflex) are common. Despite the severity of the underlying injury, the eye is typically quiet, hence the nickname “white eyed blowout fracture.”

• Urgent surgery (< 24 hours) is indicated in pediatric cases with entrapment.

Medial wall (nasoethmoidal) fracture

This involves the lacrimal and ethmoid (lamina papyracea) bones. It is occasionally associated with depressed nasal fracture, traumatic telecanthus (in severe cases), and orbital floor fracture. Complications include nasolacrimal duct injury, severe epistaxis due to anterior ethmoidal artery damage, and orbit and lid emphysema. Medial rectus entrapment is rare, and enophthalmos due to isolated medial wall fractures is extremely uncommon.

• Otolaryngology consultation is indicated in the presence of nasal fractures.

Orbital roof fracture

This is an uncommon fracture usually secondary to blunt or projectile injuries. It may involve the frontal sinus, cribriform plate, and brain. It may be associated with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or pneumocephalus.

Orbital apex fracture

This may be associated with other facial fractures and involve optic canal and superior orbital fissure. Direct traumatic optic neuropathy is likely. Complications include carotid–cavernous fistula and fragments impinging on optic nerve. These are difficult to manage due to proximity of multiple cranial nerves and vessels.

• Obvious impingement by a displaced fracture on the optic nerve may require immediate surgical intervention by an oculoplastic surgeon or neurosurgeon. High-dose systemic steroids may be given for traumatic optic neuropathy (see Chapter 11).

Tripod fracture

This involves three fracture sites: the inferior orbital rim (maxilla), lateral orbital rim (often at the zygomaticofrontal suture), and zygomatic arch. The fracture invariably extends through the orbit floor. Patients may report pain, tenderness, binocular diplopia, and trismus (pain on opening mouth or chewing). Signs include orbital rim discontinuity or palpable “step off”, malar flattening, enophthalmos, infraorbital nerve hypesthesia, orbital, conjunctival or lid emphysema, limitation of ocular movements, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, ecchymosis, and ptosis. Enophthalmos may not be appreciated on exophthalmometry due to retrodisplaced lateral orbital rim.

Le Fort fractures

These are severe maxillary fractures with the common feature of extension through the pterygoid plates:

Le Fort I low transverse maxillary bone; no orbital involvement.

Le Fort II nasal, lacrimal, and maxillary bones (medial orbital wall), as well as bones of the orbital floor and rim; may involve nasolacrimal duct.

Le Fort III extends through the medial wall, traverses the orbital floor, and through the lateral wall (craniofacial dysjunction); may involve optic canal.

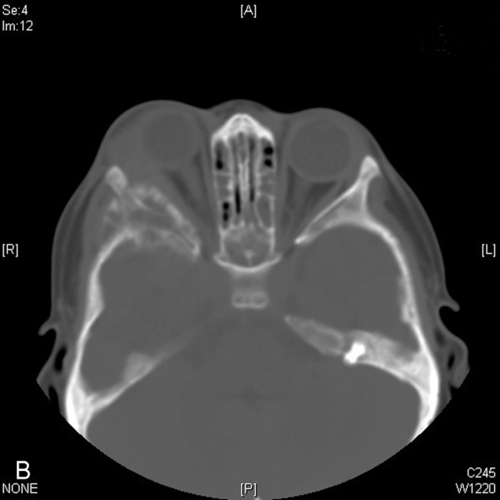

• Orbital CT scan (without contrast, direct axial and coronal views, 3 mm slices) is indicated in the presence of orbital signs (afferent papillary defect, diplopia, limited extraocular motility, proptosis, and enophthalmos) or ominous mechanism of injury (e.g., MVA, massive facial trauma). MRI is of limited usefulness in the evaluation of fractures as bones appear dark.

• Otolaryngology consultation is indicated in the presence of mandibular fracture.

• Orbital surgery consultation is indicated in the presence of isolated orbital and trimalar fractures.

• Instruct patient to avoid blowing nose. “Suck-and-spit” technique should be used to clear nasal secretions.

• Nasal decongestant (oxymetazoline hydrochloride [Afrin nasal spray] bid as needed for 3 days; Note: may cause urinary retention in men with prostatic hypertrophy).

• Ice compresses for first 48 hours.

• Systemic oral antibiotic (amoxicillin-clavulanate [Augmentin] 250–500 mg po tid for 10 days) are advocated by some.

• Nondisplaced zygomatic fractures may become displaced after initial evaluation due to masseter and temporalis contraction. Orbital or otolaryngology consultation is indicated for evaluation of such patients.

Penetrating Trauma

These may result from either a projectile (e.g., pellet gun) or stab (e.g., knife, tree branch) injury. Foreign body should be suspected even in the absence of significant external wounds.

Intraorbital Foreign Body

Retained orbital foreign body with or without associated ocular and optic nerve involvement. Inert foreign body (FB) (e.g., glass, lead, BB, plastics) may be well tolerated, and should be evaluated by an oculoplastic surgeon in a controlled setting. Organic matter carries significant risk of infection and should be removed surgically. Long-standing iron FB can produce iron toxicity (siderosis) including retinopathy.

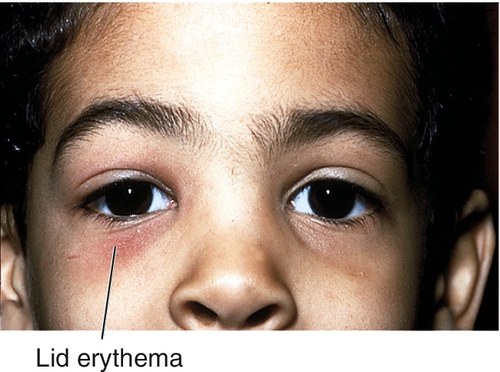

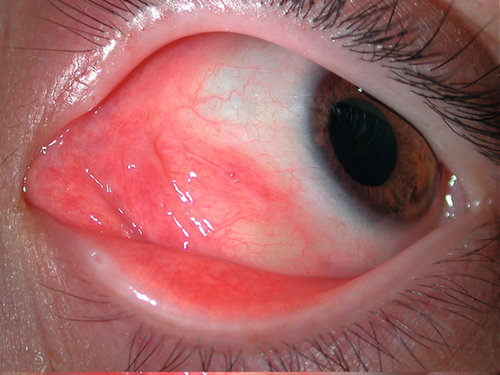

Patients may be asymptomatic or may report pain or decreased vision. Critical signs include eyelid or conjunctival laceration. Other signs may include ecchymosis, lid edema and erythema, conjunctival hemorrhage or chemosis, proptosis, limitation of ocular movements, and chorioretinitis sclopetaria (see Fig. 10-7). A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) may be present. Prognosis is generally good if the globe and optic nerve are not affected.

• Lab tests: Culture entry wound for bacteria and fungus. Serum lead levels should be monitored in patients with a retained lead foreign body.

• Orbital CT scan (without contrast, direct coronal and axial views). The best protocol is to obtain thin-section axial CT scans (0.625–1.25 mm, depending on the capabilities of the scanner), then to perform multiplanar reformation to determine character and position of foreign body. MRI is contraindicated if foreign body is metallic.

• If there is no ocular or optic nerve injury, small inert foreign bodies posterior to the equator of the globe usually are not removed but observed.

• Patients are placed on systemic oral antibiotic (amoxicillin-clavulanate [Augmentin] 500 mg po tid for 10 days) and are followed up the next day.

• Tetanus booster (tetanus toxoid 0.5 mL IM) if necessary for prophylaxis (> 7 years since last tetanus shot or if status is unknown).

• Indications for surgical removal include fistula formation, infection, optic nerve compression, large foreign body, or easily removable foreign body (usually anterior to the equator of the globe). Surgery should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon. Organic material should be removed more urgently.

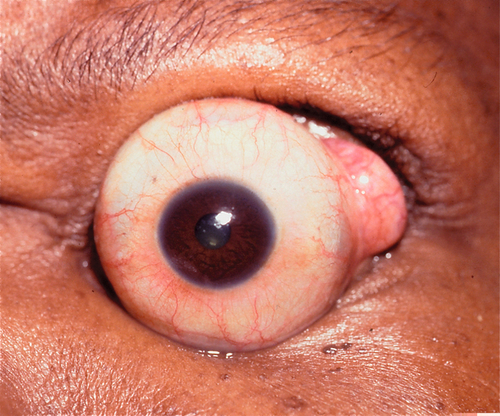

Globe Subluxation

Definition

Spontaneous forward displacement of the eye so that the equator of the globe protrudes in front of the eyelids, which retract behind the eye.

Etiology

Most often spontaneous in patients with proptosis (e.g., Graves’ disease), but may be voluntary or traumatic.

Mechanism

Pressure against the globe, typically from spreading the eyelids, causes the eye to move forward, and then when a blink occurs, the eyelids contract behind the eye locking the globe in a subluxed position.

Epidemiology

Occurs in individuals of any age (range 11 months to 73 years) and has no sex or race predilection. Risk factors include eyelid manipulation, exophthalmos, severe eyelid retraction, floppy eyelid syndrome, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, and shallow orbits (i.e., Crouzon’s or Apert’s syndrome).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have pain, blurred vision, and anxiety.

Signs

Dramatic proptosis of the eye beyond the eyelids. Depending on the length of time the globe has been subluxed, may have exposure keratopathy, corneal abrasions, blepharospasm, and optic neuropathy.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history with attention to previous episodes and potential triggers.

• Complete eye exam (after the eye has been repositioned) with attention to visual acuity, pupils, motility, exophthalmometry, lids, cornea, and ophthalmoscopy.

Prognosis

Good unless complications develop.

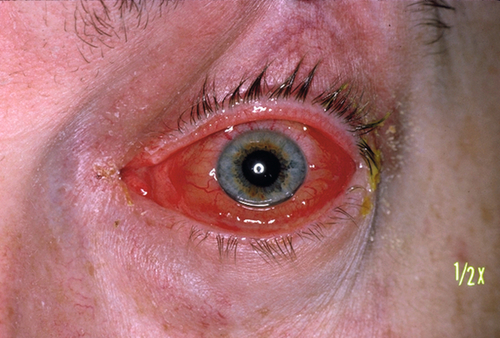

Carotid–Cavernous and Dural Sinus Fistulas

Definition

Arterial venous connection between the carotid artery and cavernous sinus; there are two types:

High-Flow Fistula

Between the cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery (carotid–cavernous fistula).

Low-Flow Fistula

Between small meningeal arterial branchesz and the dural walls of the cavernous sinus (dural sinus fistula).

Etiology

High-Flow Fistula

Spontaneous; occurs in patients with atherosclerosis and hypertension with carotid aneurysms that rupture within the sinus, or secondary to closed head trauma (basal skull fracture).

Low-Flow Fistula

Slower onset compared with the carotid–cavernous variant; dural sinus fistula is more likely to present spontaneously.

Symptoms

May hear a “swishing” noise (venous souffle); may have red “bulging” eye.

Signs

High-Flow Fistula

May have orbital bruit, pulsating proptosis, chemosis, epibulbar injection and vascular tortuosity (conjunctival corkscrew vessels), congested retinal vessels, and increased intraocular pressure.

Low-Flow Fistula

Mild proptosis and orbital congestion. However, in more severe cases findings similar to those described for carotid–cavernous fistula may occur.

Differential Diagnosis

Orbital varices that expand in a dependent position or during Valsalva maneuvers and may produce hemorrhage with minimal trauma. Carotid–cavernous fistula may also be mistaken for orbital inflammatory syndrome and occasionally uveitis.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to orbital auscultation, exophthalmometry, conjunctiva, tonometry, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Orbital CT scan or MRI: Enlargement of superior ophthalmic vein.

• Arteriography usually is required to identify the fistula; CTA and MRA have largely replaced conventional angiography.

Prognosis

Up to 70% of dural sinus fistulas may resolve spontaneously.

Infections

Preseptal Cellulitis

Definition

Infection of the eyelids not extending posterior to the orbital septum. The globe and orbit are not involved.

Etiology

Usually follows periorbital trauma or dermal infection. Suspect Staphylococcus aureus in traumatic cases. Haemophilus influenzae (nontypeable) in children less than 5 years old.

Symptoms

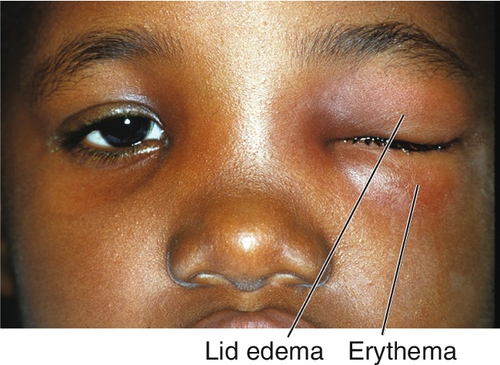

Eyelid swelling, redness, ptosis, and pain; low-grade fever.

Signs

Eyelid erythema, edema, ptosis, and warmth (may be quite dramatic); visual acuity is normal; full ocular motility without pain; no proptosis; the conjunctiva and sclera appear uninflamed; an inconspicuous lid wound may be visible; an abscess may be present.

Differential Diagnosis

Orbital cellulitis, idiopathic orbital inflammation, dacryoadenitis, dacryocystitis, conjunctivitis, and trauma.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, color vision, pupils, motility, exophthalmometry, lids, conjunctiva, and sclera.

• Check vital signs, head and neck lymph nodes, meningeal signs (nuchal rigidity), and sensorium.

• Lab tests: Complete blood count (CBC) with differential, blood cultures; wound culture if present.

• Orbital and sinus CT scan in the absence of trauma or in the presence of orbital signs to look for orbital extension and paranasal sinus opacification.

Prognosis

Usually good when treated early.

Orbital Cellulitis

Definition

Infection extending posterior to the orbital septum. May occur in combination with preseptal cellulitis.

Etiology

Most commonly secondary to ethmoid sinusitis. May also result from frontal, maxillary, or sphenoid infection. Other causes include dacryocystitis, dental caries, intracranial infections, trauma, and orbital surgery. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species are most common isolates. Haemophilus influenzae (nontypeable) in children under 5 years old. Fungi in the group Phycomycetes (Absidia, Mucor, or Rhizopus) are the most common causes of fungal orbital infection causing necrosis, vascular thrombosis, and orbital invasion. Fungal infections usually occur in immunocompromised patients (e.g., those with diabetes mellitus, metabolic acidosis, malignancy, or iatrogenic immunosuppression); and can be fatal due to intracranial spread.

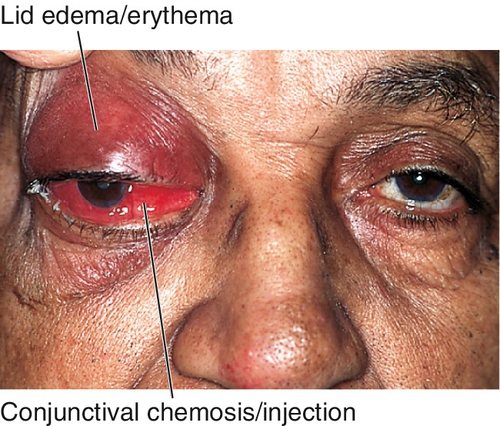

Symptoms

Decreased vision, pain, red eye, headache, diplopia, “bulging” eye, lid swelling, and fever.

Signs

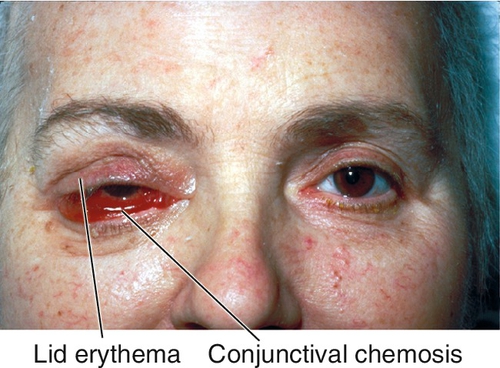

Decreased visual acuity, fever, lid edema, erythema, and tenderness, limitation of or pain on extraocular movements, proptosis, relative afferent pupillary defect, conjunctival injection and chemosis; may have optic disc swelling; fungal infection usually manifests with proptosis and orbital apex syndrome (see Chapter 2). The involvement of multiple cranial nerves suggests extension posteriorly to the orbital apex and / or cavernous sinus.

Differential Diagnosis

Thyroid-related ophthalmopathy (adults), idiopathic orbital inflammation, subperiosteal abscess, orbital neoplasm (e.g., rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoproliferative disease, ruptured dermoid cyst), orbital vasculitis, trauma, carotid–cavernous fistula, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, color vision, pupils, motility, exophthalmometry, lids, conjunctiva, cornea (including corneal sensitivity), CN V sensation, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Check vital signs, head and neck lymph nodes, meningeal signs (nuchal rigidity), and sensorium. Look in the mouth for evidence of fungal involvement.

• Lab tests: CBC with differential, blood cultures (results usually negative in phycomycosis); culture wound, if present.

• CT scan of orbits and paranasal sinuses (with contrast, direct coronal and axial views, 3 mm slices) to look for sinus opacification or abscess.

Prognosis

Depends on organism and extent of disease at the time of presentation. May develop orbital apex syndrome, cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, or permanent neurologic deficits. Mucormycosis in particular may be fatal.

Inflammation

Thyroid-Related Ophthalmopathy

Definition

An immune-mediated disorder usually occurring in conjunction with Graves’ disease that causes a spectrum of ocular abnormalities. Also called dysthyroid orbitopathy or ophthalmopathy or Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

Epidemiology

Most common cause of unilateral or bilateral proptosis in adults; female predilection (8:1); > 90% of patients have abnormal thyroid function test results; hyperthyroidism is most common (93%), although patients may be hypothyroid (6%) or euthyroid (1%); 1% of patients have or will develop myasthenia gravis. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for thyroid disease and greatly increases the incidence of thyroid-related ophthalmopathy (TRO) in patients with Graves’ disease.

Symptoms

Note: Signs and symptoms reflect four clinical components of this disease process: eyelid disorders, eye surface disorders, ocular motility disorders, and optic neuropathy.

May have red eye, foreign body sensation, tearing, decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, binocular diplopia, or prominent (“bulging”) eyes.

Signs

Eyelid retraction, edema, lagophthalmos, lid lag (von Graefe’s sign), reduced blinking, superficial keratopathy, conjunctival injection, exophthalmos, limitation of extraocular movements (supraduction most common reflecting inferior rectus involvement), positive forced ductions, resistance to retropulsion of globe, decreased visual acuity and color vision, relative afferent papillary defect, and visual field defect. A minority of cases may have acute congestion of the socket and periocular tissues. The Werner Classification of Eye Findings in Graves’ Disease (“NO SPECS”) is:

Only signs

Soft-tissue involvement (signs and symptoms)

Proptosis

Extraocular muscle involvement

Corneal involvement

Sight loss (optic nerve compression)

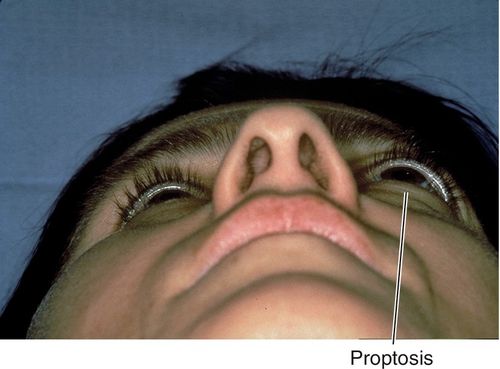

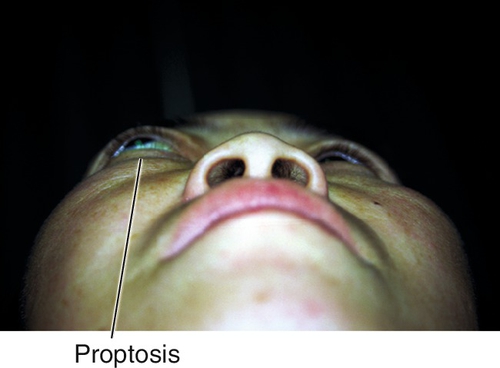

Figure 1-14 Thyroid ophthalmopathy with proptosis, lid retraction, and superior and inferior scleral show of the right eye.

Figure 1-15 Same patient as Figure 1-14, demonstrating lagophthalmos on the right side with eyelid closure (note the small incomplete closure of the right eyelids).

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic orbital inflammation, orbital and lacrimal gland tumors, orbital vasculitis, trauma, cellulitis, arteriovenous fistula, cavernous sinus thrombosis, gaze palsy, cranial nerve palsy, and physiologic exophthalmos.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to cranial nerves, visual acuity, color vision, pupils, motility, forced ductions, exophthalmometry, lids, cornea, tonometry, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Check visual fields as a baseline study in early cases and to rule out optic neuropathy in advanced cases.

• Lab tests: Thyroid function tests (thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH], thyroxine [total and free T4], and triiodothyronine [T3], and thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin [TSI]).

• Orbital CT scan (with contrast, direct coronal and axial views, 3 mm slices) or MRI with multiplanar reconstruction: Extraocular muscle enlargement with sparing of the tendons; inferior rectus is most commonly involved, followed by medial, superior, and lateral. MRI provides better imaging of the optic nerve, orbital fat, and extraocular muscle, but CT scan provides better views of bony architecture of the orbit.

• Endocrinology consultation.

Prognosis

Diplopia and ocular surface disease are common; 6% develop optic nerve disease. Despite surgical rehabilitation, which may require multiple procedures, patients are often left with functional and cosmetic deficits.

Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Disease (Orbital Pseudotumor)

Definition

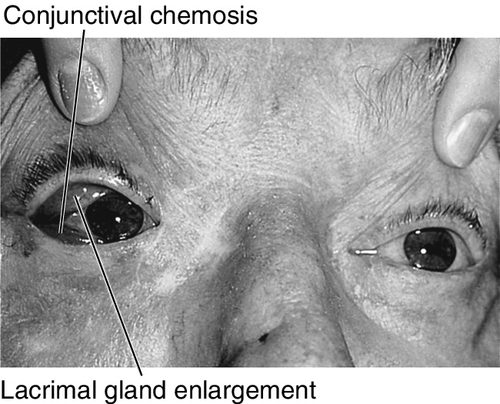

Acute or chronic idiopathic inflammatory disorder of the orbital tissues, sometimes collectively termed orbital pseudotumor. Any of the orbital tissues may be involved: lacrimal gland (dacryoadenitis), extraocular muscles (myositis), sclera (scleritis), optic nerve sheath (optic perineuritis), and orbital fat.

Tolosa–Hunt syndrome is a form of idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI) involving the orbital apex and /or anterior cavernous sinus that produces painful external ophthalmoplegia.

Epidemiology

Occurs in all age groups; usually unilateral, although bilateral disease is more common in children; adults require evaluation for systemic vasculitis (e.g., Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa) or lymphoproliferative disorders. Second most common cause of exophthalmos after thyroid eye disease. Both infectious and immune-mediated theories have been proposed.

Symptoms

Acute onset of orbital pain, decreased vision, binocular diplopia, red eye, headaches, and constitutional symptoms. (Constitutional symptoms including fever, nausea, and vomiting are present in 50% of children.)

Signs

Marked tenderness of involved region, lid edema and erythema, lacrimal gland enlargement, limitation of and pain on extraocular movements (myositis), positive forced ductions, proptosis, resistance to retropulsion of globe, induced hyperopia, conjunctival chemosis, reduced corneal sensation (due to CN V1 involvement), increased intraocular pressure; papillitis or iritis may occur and are more common in children.

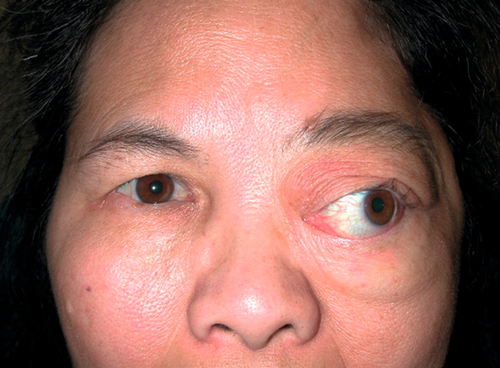

Figure 1-16 Idiopathic orbital inflammation of the right orbit with lid edema, ptosis, and chemosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, orbital cellulitis, orbital tumors, lacrimal gland tumors, orbital vasculitis, trauma, cavernous sinus thrombosis, cranial nerve palsy, and herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to eyelid and orbital palpation, pupils, motility, forced ductions, exophthalmometry, lids, cornea, tonometry, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Lab tests for bilateral or unusual cases (vasculitis suspected): CBC with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, fasting blood glucose, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), and urinalysis.

• Orbital CT scan or MRI: Thickened, enhancing sclera (ring sign), extraocular muscle enlargement with involvement of the tendons, and/or lacrimal gland involvement, diffuse inflammation with streaking of orbital fat. However, recommended imaging for idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease is contrast-enhanced thin section MRI with fat suppression.

• Consider orbital biopsy for steroid-unresponsive, recurrent, or unusual cases.

Prognosis

Generally good for acute disease, although recurrences are common. The sclerosing form of this disorder has a more insidious onset and is often less responsive to treatment.

Congenital Anomalies

Usually occur in developmental syndromes, rarely in isolation.

Congenital Anophthalmia

Absence of globe with normal-appearing eyelids due to failure of optic vesicle formation; extraocular muscles are present and insert abnormally into orbital soft tissue. Extremely rare condition that produces a hypoplastic orbit that becomes accentuated with contralateral hemifacial maturation. Usually bilateral and sporadic. Characteristic “purse stringing” of the orbital rim. Orbital CT, ultrasonography, and examination under anesthesia are required to make the diagnosis. In most cases, a rudimentary globe is present but not identifiable short of post-mortem sectioning of the orbital contents.

Microphthalmos

Small, malformed eye due to disruption of development after optic vesicle forms. More common than anophthalmos and presents similar orbital challenges. Usually unilateral and recessive. Associated with cataract, glaucoma, aniridia, coloboma, and systemic abnormalities including polydactyly, syndactyly, clubfoot, polycystic kidneys, cystic liver, cleft palate, and meningoencephalocele. True anophthalmia and severe microphthalmia can be differentiated only on histologic examination.

Microphthalmos with Cyst

Disorganized, cystic eye due to failure of embryonic fissure to close. Appears as blue mass in lower eyelid. Associated with various conditions including rubella, toxoplasmosis, maternal vitamin A deficiency, maternal thalidomide ingestion, trisomy 13, trisomy 15, and chromosome 18 deletion.

• Age of orbital maturation is not known, but elective enucleation should be deferred in early childhood. Enucleation before the age of 9 years old may produce significant orbital asymmetry (radiographically estimated deficiency up to 15%), while enucleation after 9 years old leads to no appreciable asymmetry.

• Reconstructive surgery can be undertaken after the first decade of life.

Nanophthalmos

Small eye (axial length < 20.5 mm) with normal structures; lens is normal in size but sclera and choroid are thickened. Associated with hyperopia and angle-closure glaucoma, and increased risk of choroidal effusion during intraocular surgery.

Craniofacial Disorders

Midfacial clefting syndromes can involve the medial superior or medial inferior orbit (sometimes with meningoencephalocele) and can produce hypertelorism (increased bony expanse between the medial walls of the orbit). Hypertelorism also occurs in craniosynostoses such as Crouzon’s syndrome (craniofacial dysostosis) and Apert’s syndrome (arcocephalosyndactyly) in which there is premature closure of cranial sutures. Exorbitism and lateral canthal dystopia are also found in these syndromes.

• Craniofacial surgery by an experienced oculoplastic surgeon.

Pediatric Orbital Tumors

Benign Pediatric Orbital Tumors

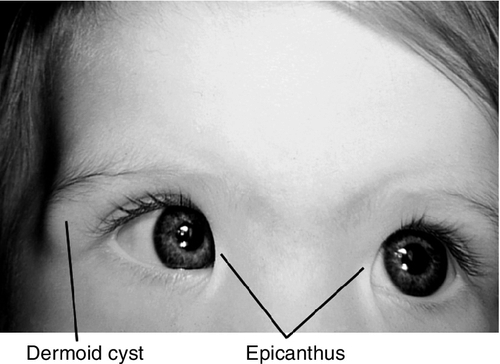

Orbital Dermoid (Dermoid Cyst)

Common, benign, palpable, smooth, painless choristoma (normal tissue, abnormal location) composed of connective tissue and containing dermal adnexal structures including sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Most common pediatric orbital tumor. Usually manifests in childhood (90% in first decade) and may enlarge slowly. Most common location is superotemporal at the zygomaticofrontal suture. Symptoms include ptosis, proptosis, and diplopia. There may be components external or internal to the orbit, or both (“dumb-bell” dermoid).

• Complete surgical excision; preserve capsule and avoid rupturing cyst to avoid recurrence and prevent an acute inflammatory process should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon.

Lymphangioma

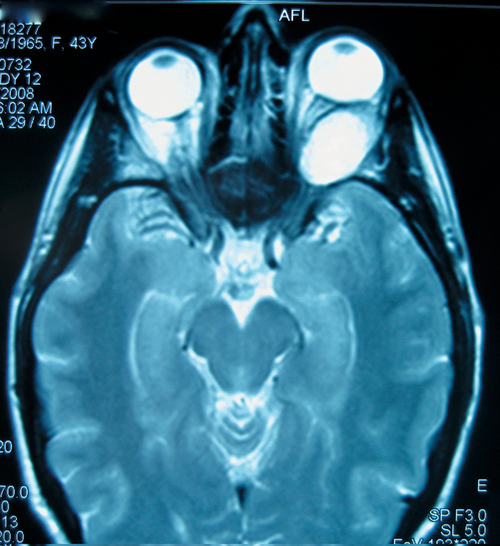

Low-flow malformations misnamed lymphangioma. Benign, nonpigmented choristoma characterized by lymphatic fluid-filled spaces lined by flattened endothelial cells; vascular channels do not contain red blood cells; patients do not produce true lymphatic vessels. May appear blue through the skin. May be associated with head and neck components. Becomes apparent in first decade with an infiltrative growth pattern or with abrupt onset due to hemorrhage within the tumor (“chocolate cyst”). May enlarge during upper respiratory tract infections. Usually presents with sudden proptosis; may have pain, ptosis, and strabismus. Complications include exposure keratopathy, compressive optic neuropathy, glaucoma, and amblyopia. Slow, relentless progression is common; may regress spontaneously.

Figure 1-21 Lymphangioma with anterior component visible as vascular subconjunctival mass at the medial canthus.

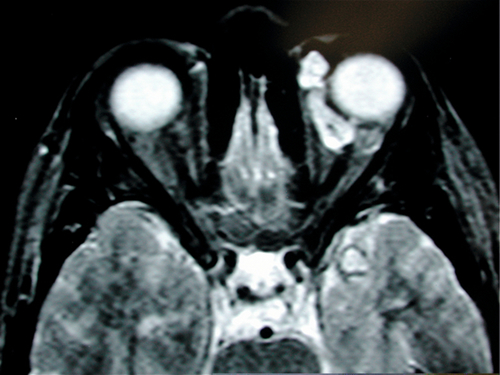

Figure 1-22 MRI (T2) of same patient as Figure 1-21 demonstrating the irregular cystic appearance of the left orbital lymphangioma.

• Orbital needle aspiration of hemorrhage (“chocolate cysts”) or surgical exploration for acute orbital hemorrhage with compressive optic neuropathy.

• Complete surgical excision is usually not possible. Limited excision indicated for ocular damage or severe cosmetic deformities; should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon.

• Consider treatment with oral sildenafil (experimental).

• Children should undergo pediatric otolaryngologic examination to rule out airway compromise.

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Nevoxanthoendothelioma, composed of histiocytes and Touton giant cells that rarely involve the orbit. Appears between birth and 1 year of age with mild proptosis. Associated with yellow-orange cutaneous lesions, and may cause destruction of bone. Spontaneous resolution often occurs. Orbital ultrasound may be useful.

• Most cases can be observed with frequent spontaneous regression.

• Consider local steroid injection (controversial).

• Surgical excision in the rare case of visual compromise.

Histiocytic Tumors

Initially designated Histiocytosis X, the Langerhans’ cell histiocytoses comprise a spectrum of related granulomatous diseases that occur most frequently in children aged 1–4 years old. Immunohistochemical staining and electron microscopy reveals atypical (Langerhans’) histiocytes (+ CD1a) with characteristic Birbeck’s (cytoplasmic) granules on electron microscopy.

Hand–Schüller–Christian disease

Chronic, recurrent form. Classic triad of proptosis, lytic skull lesions, and diabetes insipidus.

• Treatment is with systemic glucocorticoids and chemotherapy.

Letterer–Siwe disease

Acute, systemic form. Occurs during infancy with hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and fever, and with very poor prognosis for survival.

• Treatment is with systemic glucocorticoids and chemotherapy.

Eosinophilic granuloma

Localized form. Most likely to involve the orbit. Bony lesion with soft-tissue involvement that typically produces proptosis and more often is located in the superotemporal orbit as a result of frontal bone disease.

• Treatment is with local incision and curettage, intralesional steroid injection, or radiotherapy.

Malignant Pediatric Orbital Tumors

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Most common primary pediatric orbital malignancy and most common pediatric soft- tissue malignancy; mean age 5–7 years old; 90% of cases occur in patients under 16 years old; male predilection (5:3). Presents with rapid onset, progressive, unilateral proptosis, eyelid edema, and discoloration. Epistaxis, sinusitis, and headaches indicate sinus involvement. History of trauma may be misleading. Predilection for superonasal orbit. CT scan commonly demonstrates bony orbital destruction. Arises from primitive mesenchyme, not extraocular muscles. Urgent biopsy necessary for diagnosis. Four histologic forms:

Embryonal

Most common (70%); cross striations found in 50% of cells.

Alveolar

Most malignant, worst prognosis, inferior orbit, second most common (20–30%); few cross-striations.

Botryoid

Grape-like, originates within paranasal sinuses or conjunctiva; rare.

Pleomorphic

Rarest (< 10%), most differentiated, occurs in older patients, best prognosis; 90–95% 5-year survival rate if limited to orbit; cross-striations in most cells.

• Pediatric oncology consultation for systemic evaluation including abdominal and thoracic CT, bone marrow biopsy, and lumbar puncture.

• Treatment involves combinations of surgery, systemic chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. New protocols have improved outcomes (the IRS-IV study showed a 3-year failure-free survival rate of 91%, 94%, and 80% for groups I, II, and III disease, respectively).

Neuroblastoma

Most common pediatric orbital metastatic tumor (second most common orbital malignancy after rhabdomyosarcoma). Occurs in first decade. Usually arises from a primary tumor in the abdomen (adrenals in 50%), mediastinum, or neck from undifferentiated embryonic cells of neural crest origin. Patients typically have sudden proptosis with eyelid ecchymosis (“raccoon eyes”) that may be bilateral; may develop ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome and opsoclonus (saccadomania). Prognosis is poor.

• Orbital CT scan: Poorly defined mass with bony erosion (most commonly the lateral wall).

• Pediatric oncology consultation for systemic evaluation.

• Treatment is with local radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy.

Leukemia

Advanced leukemia, particularly the acute lymphocytic type, may appear with proptosis; granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma), an uncommon subtype of myelogenous leukemia, may also produce orbital proptosis, often prior to hematogenous or bone marrow signs. Both forms usually occur during first decade.

• Pediatric oncology consultation.

• Treatment is with systemic chemotherapy.

Adult Orbital Tumors

Benign Adult Orbital Tumors

Cavernous Hemangioma

This misnamed tumor is a vascular hamartoma and the most common adult orbital tumor. Probably present from birth, but typically appears in fourth to sixth decades. It is one of the four periocular tumors that are more common in females (meningioma, sebaceous carcinoma, and choroidal osteoma). Patients usually have painless, decreased visual acuity or diplopia. Signs include slowly progressive proptosis and compressive optic neuropathy. May have induced hyperopia and choroidal folds due to posterior pressure on the globe. May enlarge during pregnancy.

• Orbital MRI: Tumor appears hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with heterogeneous internal signal density.

• A-scan ultrasonography: High internal reflectivity.

• Complete surgical excision (usually requires lateral orbitotomy with bone removal) indicated for severe corneal exposure, compressive optic neuropathy, intractable diplopia, or exophthalmos; should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon.

Mucocele

Cystic sinus mass due to the combination of an orbital wall fracture and obstructed sinus excretory ducts, lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and filled with mucoid material. Patients usually have a history of chronic sinusitis (frontal and ethmoidal sinuses). Associated with cystic fibrosis; usually occurs in the superonasal orbit; must be differentiated from encephalocele and meningocele.

• Head and orbital CT scan: Orbital lesion and orbital wall defect with sinus opacification.

• Complete surgical excision should be performed by an oculoplastic or otolaryngology plastic surgeon. May require obliteration of frontal sinus; preoperative and postoperative systemic antibiotics (ampicillin-sulbactam [Unasyn] 1.5–3.0 g IV q6h).

Neurilemoma (Schwannoma)

Rare, benign tumor (1% of all orbital tumors) that occurs in young to middle-aged individuals. Patients have gradual, painless proptosis and globe displacement. May be associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. One of two truly encapsulated orbital tumors. Histologic examination demonstrates two patterns of Schwann cell proliferation enveloped by perineurium: Antoni A (solid, nuclear palisading, Verocay bodies) and Antoni B (loose, myxoid areas). Recurrence and malignant transformation are rare.

• A-scan ultrasonography: Low internal reflectivity.

• Complete surgical excision should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon.

Meningioma

Symptoms relate to specific location, but proptosis, globe displacement, diplopia, and optic neuropathy are common manifestations. Median age at diagnosis is 38 years old with female predilection (3:1). See Chapter 11 for complete discussion.

Figure 1-30 Sphenoid wing meningioma producing proptosis and exotropia of the left eye.

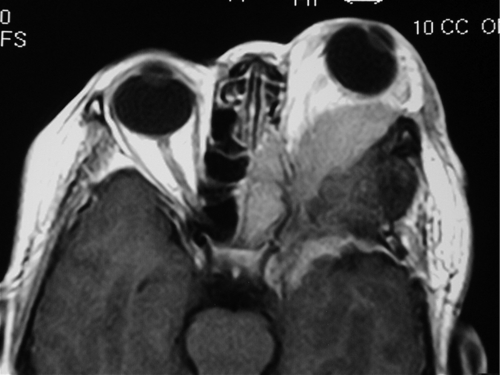

Figure 1-31 MRI (T1) of same patient as Figure 1-30 demonstrating the orbital mass and globe displacement.

Primary orbital meningioma

Typically arises from the optic nerve (see Chapter 11).

Sphenoid meningioma

Usually arises intracranially with expansion into the orbit.

Fibrous Histiocytoma

Most common mesenchymal orbital tumor, but extremely rare. Firm, well-defined lesion that is usually located in the superonasal quadrant. Occurs in middle-aged adults. Less than 10% have metastatic potential. Histologically, cells have a cartwheel or storiform pattern. Recurrence is often more aggressive, with possible malignant transformation.

• Complete surgical excision should be performed by an oculoplastic surgeon.

Fibro-Osseous Tumors

Fibrous dysplasia

Nonmalignant, painless, bony proliferation often involving single (monostotic) or multiple (polyostotic) facial and orbital bones, occurs in Albright’s syndrome. Most appear in first decade, with rapid growth during puberty and little growth during adulthood. Most patients will have pathologic long-bone fractures.

Osteoma

Rare, slow-growing, benign bony tumor frequently involving frontal and ethmoid sinuses. Causes globe displacement away from tumor. Surgical intervention is usually palliative and clinical cure almost impossible. However, many are found incidentally, most are nonprogressive, and surgical excision /debridement is rarely indicated.

• Orbital CT scan: Well-circumscribed lesion with calcifications.

• Osteoma usually can be excised completely if visual function threatened or intracranial extension.

• Should be evaluated by an oculoplastic surgeon.

• Consider otolaryngology consultation.

Cholesterol Granuloma

Idiopathic hemorrhagic lesion of orbital frontal bone, usually occurring in males. Causes proptosis, blurred vision, diplopia, and a palpable mass. Surgical excision is curative.

• Orbital CT scan: Well-defined superotemporal mass with bony erosion.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Idiopathic, osteolytic, expansile mass typically found in long bones of the extremities or less commonly in the superior orbit. Occurs during adolescence. Intralesional hemorrhage produces proptosis, diplopia, and cranial nerve palsies.

• Orbital CT scan: Well-defined soft-tissue mass with bony lysis.

Malignant Adult Orbital Tumors

Lymphoid Tumors

Lymphoid infiltrates account for 10% of orbital tumors. The noninflammatory orbital lymphoid infiltrates are classified as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma. Often clinically indistinguishable, the diagnosis is made by microscopic morphology and immunophenotyping. Most orbital lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s low-grade B-cell variety. Most common in patients 50–70 years old; extremely rare in children; more common in women than in men (3:2). Patients have painless proptosis, diplopia, decreased visual acuity (induced hyperopia), or a combination of these symptoms. Lesions may be intraconal, extraconal, or both. Fifty percent of patients with orbital lymphoma eventually develop systemic involvement; risk of systemic disease is lower in cases of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. Radiation adequately controls local disease in nearly 100% of cases. Systemic disease is usually treated with chemotherapy. Good prognosis with 90% 5-year survival.

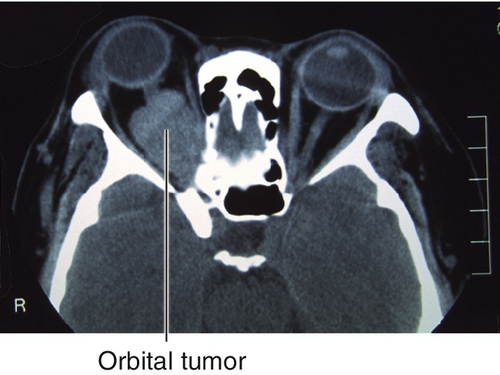

Figure 1-32 Right proptosis from orbital lymphoid tumor.

Figure 1-33 Orbital CT of same patient as Figure 1-32 demonstrating the orbital lymphoid tumor and proptosis.

• Tissue biopsy and immunohistochemical studies on fresh (not preserved) specimens required for diagnosis.

• Reactive infiltrates demonstrate follicular hyperplasia without a clonal population of cells.

• Lymphoma is diagnosed in the presence of monoclonality, specific gene rearrangements assessed with PCR, or sufficient cytologic and architectural atypia; nearly always extranodal B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas; greater than 50% are MALT-type lymphomas.

• Multiclonal infiltrates not fulfilling the criteria to be diagnosed as lymphoma may progress to malignant lymphoma.

• Systemic evaluation by internist or oncologist in the presence of biopsy-proven orbital lymphoma: includes thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT scan, whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) scan, complete blood count (CBC) with differential, serum protein electrophoresis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and possibly bone scan; bone marrow biopsy is reserved by select cases.

• Treatment of ocular adnexal lymphoma depends on the stage and histologic classification. For isolated low-grade ocular adnexal lymphoma, external-beam radiation therapy is considered the standard therapy. For more widespread disease or for higher-grade lymphomas, systemic chemotherapy or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy is needed.

Fibro-Osseous Tumors

Chondrosarcoma

Usually occurs after age 20 years old with slight female predilection; often bilateral with temporal globe displacement. Intracranial extension is often fatal.

• Orbital CT scan: Irregular lesion with bony erosion.

Osteosarcoma

Common primary bony malignancy; usually occurs before age 20 years old.

• Orbital CT scan: Lytic lesion with calcifications.

Metastatic Tumors

Metastases account for 10% of all orbital tumors but are the most common orbital malignancy. Most common primary sources are breast, lung (bronchogenic), prostate, and gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms include rapid-onset, painful proptosis, limitation of extraocular movements, and diplopia. Visual acuity may be normal. Scirrhous carcinoma of the breast characteristically causes enophthalmos from orbital fibrosis.

• Orbital CT scan: Bony erosion and destruction of adjacent structures.

• Local radiotherapy for palliation should be performed by a radiation oncologist experienced in orbital processes.

• Palliative surgical debulking /excision may be considered in cases with intractable pain.

• Hematology and oncology consultation.

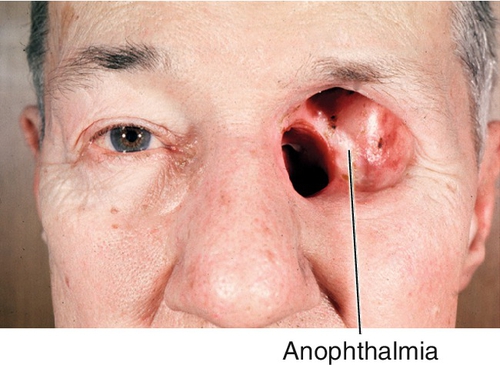

Acquired Anophthalmia

Absence of the eye resulting from enucleation or evisceration of the globe due to malignancy, trauma, or pain and blindness; more common in men than women. Inflammation or infection of the socket or implant may present with copious mucopurulent discharge, pain greater in one direction of eye movement, or serosanguinous tears; pain is qualitatively different from pre-enucleation pain; signs may include inflamed conjunctiva, dehiscence or erosion of conjunctiva with exposure of implant, blepharitis, or cellulitis.

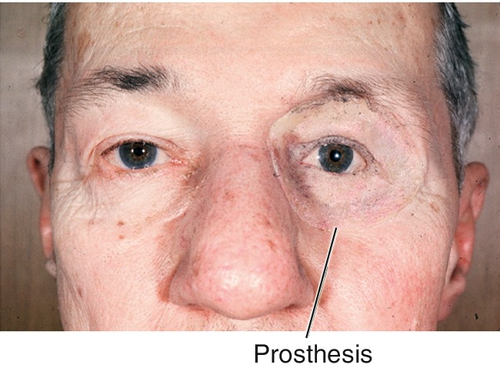

Figure 1-34 Acquired anophthalmia of the left eye secondary to evisceration for orbital tumor.

Figure 1-35 Same patient as Figure 1-34 with prosthesis in place.

• Eyelids should be observed for cellulitis, ptosis, or retraction.

• Superior tarsal conjunctiva must be examined for giant papillae (see Chapter 4).

• In the absence of conjunctival defect or lesion, treat with broad-spectrum topical antibiotic (gentamicin or polymyxin B sulfate [Polytrim] 1 gtt qid).

• If conjunctival defect is observed, refer to an oculoplastic surgeon for evaluation. Treatment may include removal of avascular portion of porous implant, secondary implant, dermis fat graft placement, or other techniques.

• Exposed implant is at risk for orbital cellulitis and should be treated with systemic oral antibiotic, surgically, or both:

• Cephalexin 250–500 mg po qid or

• Amoxicillin-clavulanate [Augmentin] 250–500 mg po tid.

• Orbital prosthesis should be replaced with orbital conformer during period of infection. If conjunctival defect is present, the prosthesis must be reconstructed by ocularist postoperatively while conformer is used for 1 month.

• Socket should not be left without prosthesis or conformer for longer than 24 hours (controversial) due to conjunctival cicatrization, forniceal foreshortening, and socket contracture.

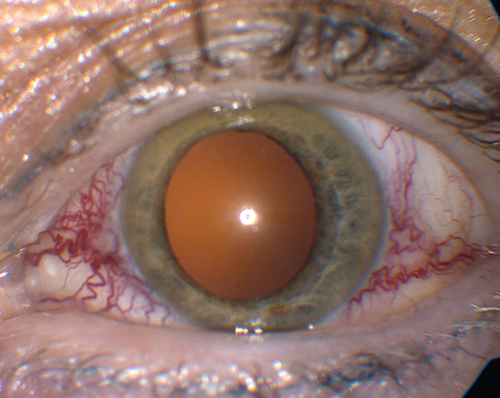

Atrophia Bulbi and Phthisis Bulbi

Progressive functional ocular decompensation, after either accidental or surgical trauma, the end stage of which is called phthisis bulbi. Three stages exist.

Atrophia Bulbi Without Shrinkage

Globe shape and size are normal, but with cataract, retinal detachment, synechiae, or cyclitic membranes.

Atrophia Bulbi With Shrinkage

Soft and smaller globe with decreased intraocular pressure; collapse of the anterior chamber; edematous cornea with vascularization, fibrosis, and opacification.

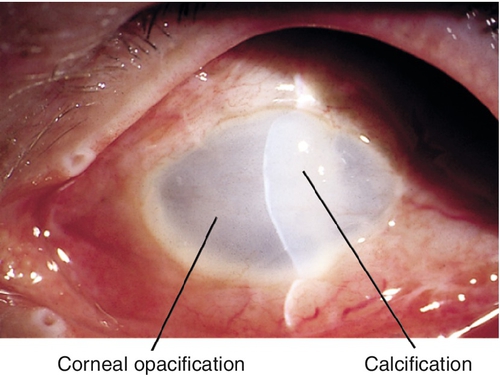

Atrophia Bulbi With Disorganization (Phthisis Bulbi)

Globe approximately two-thirds normal size with thickened sclera, intraocular disorganization, and calcification of cornea, lens, and retina; spontaneous hemorrhages or inflammation can occur, and bone may be present in the uveal tract. These eyes usually have no vision, and they carry an increased risk of intraocular malignancies.

• B-scan ultrasonography should be performed annually to rule out intraocular malignancies.

• Blind, painful eyes are first treated with topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% qid) and a cycloplegic (atropine 1% tid). Consider retrobulbar alcohol or chlorpromazine (Thorazine) injection for severe ocular pain.

• Cosmetic shell can be created by an ocularist and is worn over the phthisical eye to improve appearance and support the eyelid.

• Enucleation typically relieves pain permanently and can improve cosmesis in many cases.

• Modern enucleation techniques involve porous orbital implants with extraocular muscles attached, allowing for natural-appearing movement of the prosthesis.