2

Ocular Motility and Cranial Nerves

Strabismus

Definition

Ocular misalignment that may be horizontal or vertical; comitant (same angle of deviation in all positions of gaze) or incomitant (angle of deviation varies in different positions of gaze); latent, manifest, or intermittent.

Phoria

Latent deviation.

Tropia

Manifest deviation.

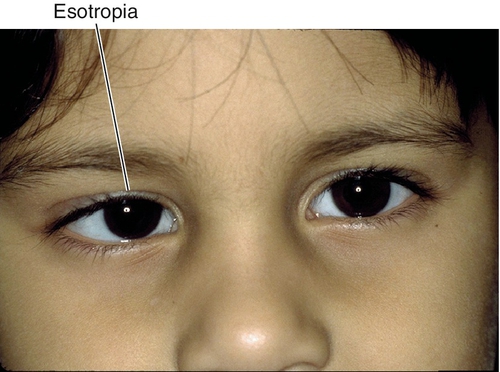

Esotropia

Inward deviation.

Exotropia

Outward deviation.

Hypertropia

Upward deviation.

Hypotropia

Downward deviation (vertical deviations usually are designated by the hypertropic eye, but if the process clearly is causing one eye to turn downward, this eye is designated hypotropic).

Etiology

Congenital or acquired local or systemic muscle, nerve, or neuromuscular abnormality; childhood forms are usually idiopathic. See below for full description of the various types of strabismus (horizontal, vertical, miscellaneous forms). See also cranial nerve palsy, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), and myasthenia gravis.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have eye turn, head turn, head tilt, decreased vision, binocular diplopia (in older children and adults), headaches, asthenopia, and eye fatigue.

Signs

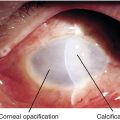

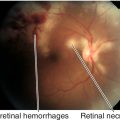

Normal or decreased visual acuity (amblyopia), strabismus, limitation of ocular movements, reduced stereopsis; may have other ocular pathology (i.e., corneal opacity, cataract, aphakia, retinal detachment, optic atrophy, macular scar, phthisis) causing a secondary sensory deprivation strabismus (usually esotropia in children < 6 years old, exotropia in older children and adults).

Differential Diagnosis

See above; pseudostrabismus (epicanthal fold), negative angle kappa (pseudoesotropia), positive angle kappa (pseudoexotropia), dragged macula (e.g., retinopathy of prematurity, toxocariasis).

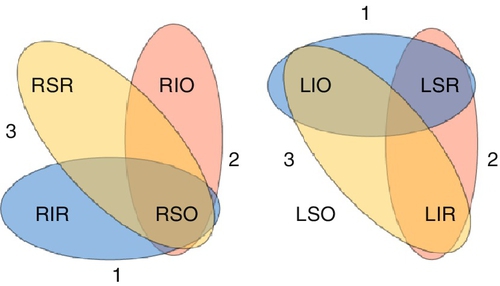

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, refraction, cycloplegic refraction, pupils, motility (versions, ductions, cover and alternate cover test), measure deviation (Hirschberg, Krimsky, or prism cover tests), measure torsional component (double Maddox rod test), Parks–Bielschowsky three-step test (identifies isolated cyclovertical muscle palsy [see Fourth Cranial Nerve Palsy section]), head posture, stereopsis (Titmus stereoacuity test, Randot stereotest), suppression/anomalous retinal correspondence (Worth 4-dot, 4 prism diopter [PD] base-out prism, Maddox rod, red glass, Bagolini’s striated lens, or after-image tests), fusion (amblyoscope, Hess screen tests), forced ductions, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Orbital computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in select cases.

• Lab tests: Thyroid function tests (triiodothyronine [T3], thyroxine [T4], thyrotropin [TSH]) in cases of muscle restriction, and antiacetylcholine (anti-ACh) receptor antibody titers if myasthenia gravis is suspected. Electrocardiogram in patients with chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) to rule out heart block in Kearns–Sayre syndrome. Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Neurology consultation and brain MRI if cranial nerves are involved.

• Medical consultation for dysthyroid and myasthenia patients.

Prognosis

Usually good; depends on etiology.

Horizontal Strabismus

Esotropia

Eye turns inward; most common ocular deviation (> 50%).

Infantile Esotropia

Appears by age 6 months with a large, constant angle of deviation (80% > 35 PD); often cross-fixate; normal refractive error; positive family history is common; may be associated with inferior oblique overaction (70%), dissociated vertical deviation (DVD) (70%), latent nystagmus, and persistent smooth pursuit asymmetry.

• Treat amblyopia with occlusive therapy of fixating or dominant eye before performing surgery.

• Correct any hyperopia greater than + 2.00 diopters (D).

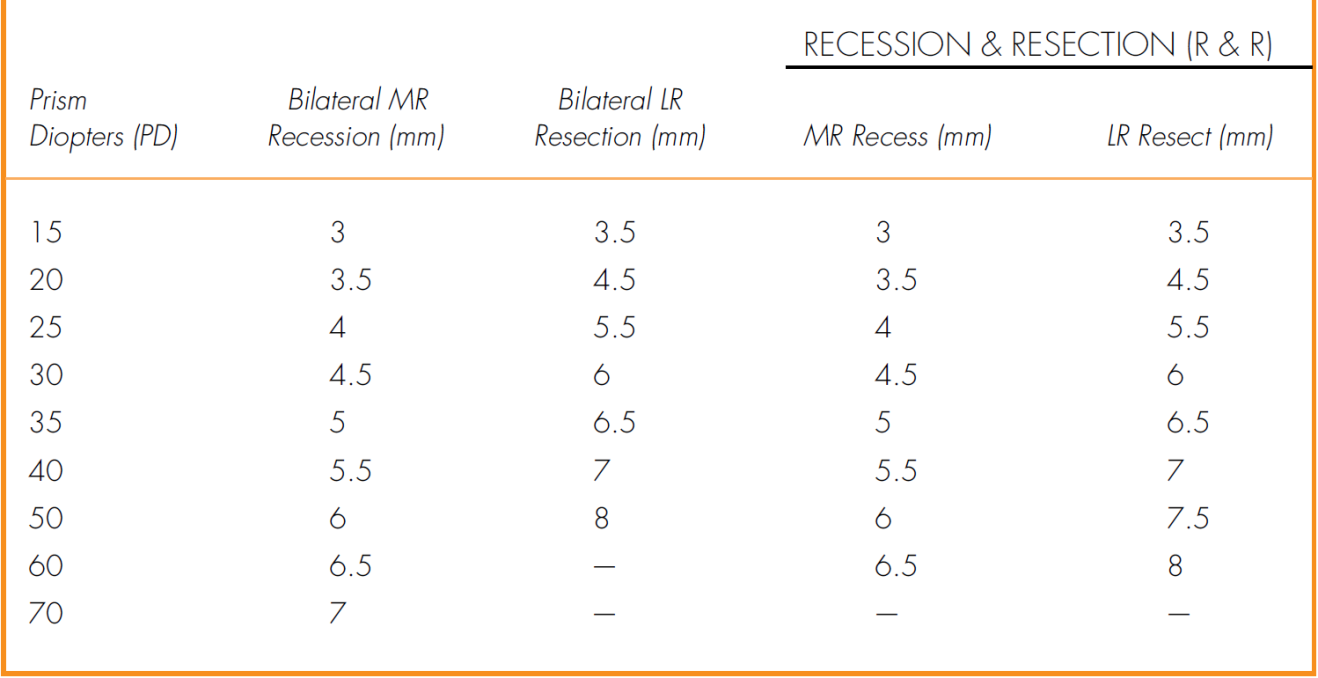

• Muscle surgery should be performed early (6 months to 2 years): bilateral medial rectus recession or unilateral recession of medial rectus and resection of lateral rectus; additional surgery for inferior oblique overaction, dissociated vertical deviation (DVD), and overcorrection and undercorrection is necessary in a large percentage of cases.

Accommodative Esotropia

Develops between age 6 months and 6 years, usually around age 2 years, with variable angle of deviation (eyes usually straight as infant); initially intermittent when child is tired or sick. There are three types:

Refractive

Usually hyperopic (average + 4.75D), normal accommodative convergence-to-accommodation (AC / A) ratio (3 : 1PD to 5 : 1PD per diopter of accommodation), esotropia at distance (ET) similar to that at near (ET’).

Nonrefractive

High AC / A ratio; esotropia at near greater than at distance (ET’ > ET).

• Methods of calculating AC / A ratio

(2) Lens gradient method: AC / A = (WL − NL)/ D

WL, deviation with lens in front of eye; NL, deviation with no lens in front of eye; D, dioptric power of lens used.

Mixed

Not completely correctable with single-vision or bifocal glasses.

• Muscle surgery as above should be performed if residual esotropia is greater than 10PD.

Acquired Nonaccommodative Esotropia and Other Forms of Esotropia

Due to stress, sensory deprivation, divergence insufficiency (ET ≥ ET’), spasm of near reflex, consecutive (after exotropia surgery), or cranial nerve (CN) VI palsy.

• Muscle surgery can be considered either in symptomatic cases or if angle of deviation is large (Table 2-1).

• If no evident cause, MRI indicated to rule out Arnold–Chiari malformation.

Cyclical esotropia

Very rare form of nonaccommodative ET (1 : 3000); occurs between 2 and 6 years of age; child is usually orthophoric (eyes straight) but develops esotropia for 24-hour to 48-hour periods; can progress to constant esotropia.

• Correct any hyperopia greater than + 3.00D.

• Muscle surgery as above can be performed when deviation stabilizes.

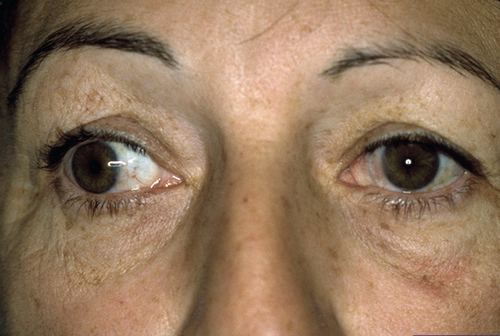

Exotropia

Eye turns outward; may be intermittent (usually at age 2 years, amblyopia rare) or constant (rarely congenital, consecutive [after esotropia surgery], due to decompensated intermittent exotropia [XT] or from sensory deprivation [in children > 5 years of age]); amblyopia rare due to alternate fixation or formation of anomalous retinal correspondence.

Basic Exotropia

Exotropia at distance (XT) equal to that at near (XT’); normal AC / A ratio, normal fusional convergence.

Convergence Insufficiency

Inability to adequately converge while fixating on an object as it moves from distance to near (increased near point of convergence); exotropia at near greater than at distance (XT’ > XT); reduced fusional convergence amplitudes. Rare before 10 years of age; slight female predilection. Symptoms often begin during teen years with asthenopia, difficulty reading, blurred near vision, diplopia, and fatigue. Common in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, and with traumatic brain injury; may rarely be associated with accommodative insufficiency and ciliary body dysfunction.

• Consider muscle surgery: bilateral medial rectus resection should be used with caution owing to the risk of disrupting alignment at distance.

• Orthoptic exercises are controversial: near-point pencil push-ups (bring pencil in slowly from distance until breakpoint reached, then repeat 10–15 times) is the most common but is minimally effective; saccadic exercises or prism convergence exercises (increase amount of base-out prism until breakpoint reached, then repeat starting with low prism power 10–15 times) are more effective.

Pseudodivergence Excess

XT > XT’ except after prolonged patching (patch test) when near deviation increases (full latent deviation); near deviation also increases with + 3.00D lens; may have high AC / A ratio.

True Divergence Excess

XT > XT’ even after patch test; may have high AC / A ratio.

• Consider base-in prism lenses to help with convergence.

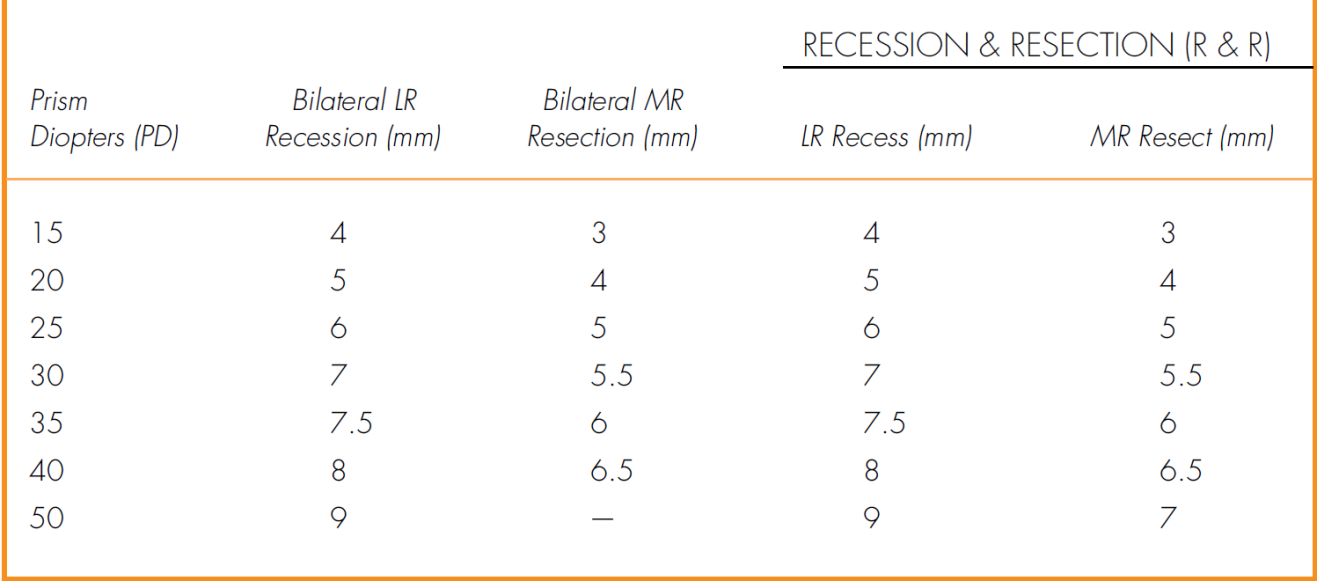

• Muscle surgery if the patient manifests exotropia over 50% of the time and is older than 4 years old: bilateral lateral rectus recession; consecutive esotropia (postoperative diplopia) can be managed with prisms or miotics unless it lasts more than 8 weeks, then reoperate (Table 2-2).

A-, V-, and X-Patterns

Amount of horizontal deviation varies from upgaze to downgaze; occurs in up to 50% of strabismus.

A-pattern

Amount of horizontal deviation changes between upgaze (larger esotropia in upgaze) and downgaze (larger exotropia in downgaze); more common with exotropia; clinically significant if difference is 10PD or greater; associated with superior oblique muscle overaction; patients may have chin-up position.

• Absolutely no superior oblique tenotomies if patient is bifixator with 40 seconds of arc of stereoacuity.

V-pattern

Amount of horizontal deviation changes between upgaze (larger exotropia in upgaze) and downgaze (larger esotropia in downgaze); more common with esotropia; clinically significant if difference is 15PD or greater; associated with inferior oblique muscle overaction, increased lateral rectus muscle innervation, underaction of superior rectus muscle, Apert’s syndrome, and Crouzon’s syndrome; patients may have chin-down position.

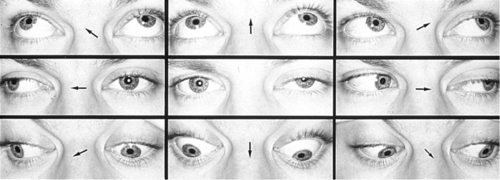

Figure 2-5 V-pattern esotropia demonstrating reduced esotropia in upgaze.

Figure 2-6 Same patient as shown in Figure 2-5, demonstrating increased esotropia in downgaze.

X-pattern

Larger exotropia in upgaze and downgaze than in primary position; due to secondary contracture of the oblique muscles or the lateral recti, causing a tethering effect in upgaze and downgaze.

Vertical Strabismus

Brown’s Syndrome (Superior Oblique Tendon Sheath Syndrome)

Congenital or acquired anomaly of the superior oblique tendon sheath, causing an inability to elevate the affected eye especially in adduction. Elevation in abduction is normal or slightly decreased; may have hypotropia in primary gaze causing a chin-up position, positive forced duction testing that is worse on retropulsion and when moving eye up and in (differentiates from inferior rectus restriction, which is worse with proptosing eye); V-pattern (differentiates from superior oblique overaction, which is A-pattern), no superior oblique overaction, down-shoot in adduction, and widened palpebral fissures on adduction in severe cases. Ten percent bilateral, female predilection (3 : 2) affects right eye more often than left eye. Acquired forms are associated with rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, sinusitis, surgery (sinus, orbital, strabismus, or retinal detachment), scleroderma, hypogammaglobulinemia, postpartum, and trauma.

• Consider injection of steroids near trochlea or oral steroids if inflammatory etiology exists.

• Muscle surgery for abnormal head position or large hypotropia in primary position: superior oblique muscle tenotomy or tenectomy or silicon band expander, with or without ipsilateral inferior oblique muscle recession.

Dissociated Strabismus Complex: Dissociated Vertical Deviation, Dissociated Horizontal Deviation, Dissociated Torsional Deviation

Updrift, horizontal, oblique, or torsional movement of nonfixating eye with occlusion or visual inattention. Often bilateral, asymmetric, and asymptomatic; does not obey Hering’s law (equal innervation to yoke muscles). Demonstrates Bielschowsky phenomenon (downdrift of occluded eye as increasing neutral density filters are placed over fixating eye), red lens phenomenon (when red lens held over either eye while fixating on light and the red image is always seen below the white image); associated with congenital esotropia (75%), latent nystagmus, inferior oblique overaction, and after esotropia surgery.

• No treatment usually required.

• Muscle surgery for abnormal head position or if deviation is large and constant or very frequent: bilateral superior rectus recession, inferior rectus resection, or inferior oblique weakening (Table 2-3).

Table 2-3

Surgical Numbers for Vertical Strabismus Surgery

| Dissociated Vertical Deviation | |

| Magnitude | Recess SR |

| Mild | 5 mm |

| Moderate | 7 mm |

| Severe | 10 mm |

| Inferior Oblique Overaction | |

| Magnitude | Recess IO |

| Mild | 10 mm |

| Moderate | 15 mm |

| Severe | Myectomy |

SR, superior rectus; IO, inferior oblique.

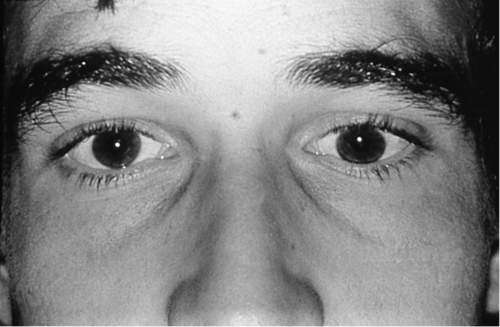

Monocular Elevation Deficiency (Double Elevator Palsy)

Sporadic, unilateral defect causing total inability to elevate one eye (may have good Bell’s reflex); hypotropia in primary position and increases on upgaze, ipsilateral ptosis common, may have chin-up head position to fuse; may be supranuclear, congenital, or acquired (due to cerebrovascular disease, tumor, or infection). Three types:

Type 1

Inferior rectus muscle restriction–unilateral fibrosis syndrome.

Type 2

Elevator weakness (superior rectus, inferior oblique)–true double elevator palsy.

Type 3

Combination (inferior rectus restriction and weak elevators).

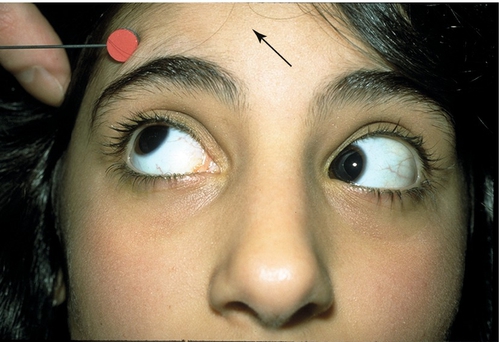

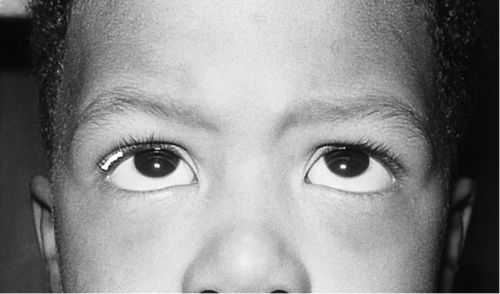

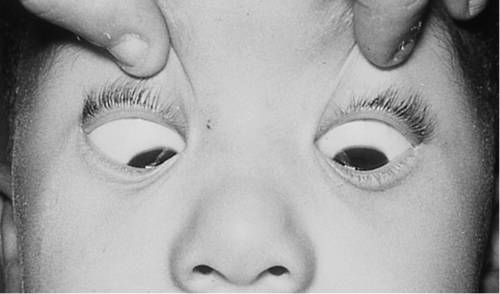

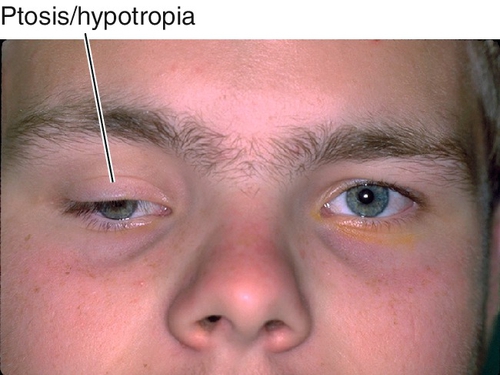

Figure 2-8 Monocular elevation deficiency (double elevator palsy) demonstrating ptosis and hypotropia of the right eye.

• May require surgery to correct residual ptosis.

Miscellaneous Strabismus

Duane’s Retraction Syndrome

Congenital agenesis or hypoplasia of the abducens nerve (CN VI) with variable dysinnervation of the lateral rectus muscle; 20% bilateral, female predilection (3 : 2), affects left eye more often than right eye (3:1). Three types (type 1 more common than type 3, and type 3 more common than type 2):

Type 1

Limited abduction; esotropia in primary position.

Type 2

Limited adduction; exotropia in primary position.

Type 3

Limited abduction and adduction.

Co-contraction of medial and lateral rectus muscles causes globe retraction and narrowing of palpebral fissure; narrowing of palpebral fissure on adduction and widening on abduction in all three types; upshoots and downshoots (leash phenomenon) common; may have head turn to fuse; amblyopia rare; rarely associated with deafness and less commonly with other ocular or systemic conditions.

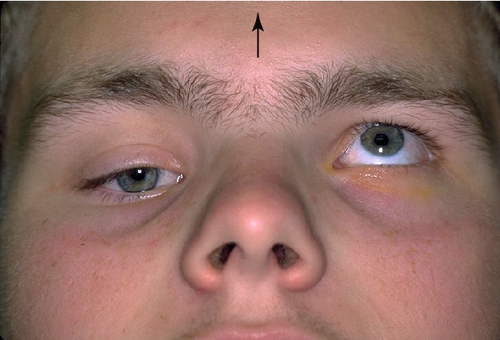

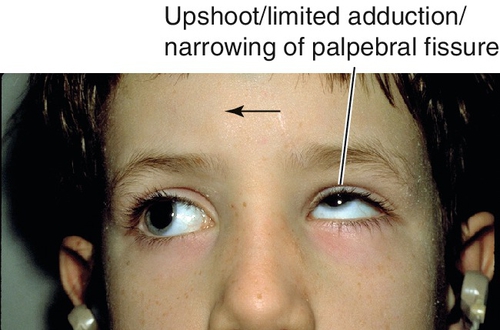

Figure 2-10 Duane’s retraction syndrome type 3, demonstrating limited adduction, upshoot (leash phenomenon) and narrowing of the palpebral fissure of the left eye.

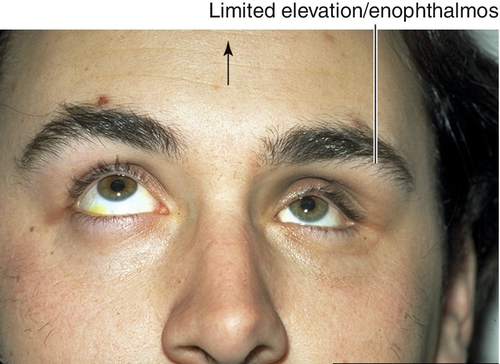

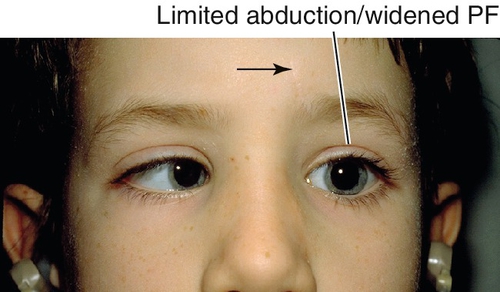

Figure 2-11 Same patient as shown in Figure 2-10, demonstrating limited abduction and widening of the palpebral fissure of the left eye.

• No treatment usually required.

• Correct any refractive error.

• Treat amblyopia.

• Muscle surgery if there is significant ocular misalignment in primary position, abnormal head position, or significant upshoot or downshoot: medial rectus muscle recession in type 1 or lateral rectus muscle recession in type 2; NEVER perform lateral rectus muscle resection. Recess medial and lateral rectus muscles in type 3 with severe retraction.

Möbius Syndrome

Congenital bilateral aplasia of CN VI and VII nuclei (CN V, IX, and XII may also be affected); inability to abduct either eye past midline; associated with esotropia, epiphora, exposure keratitis, and mask-like facies; patient may have limb deformities or absence of pectoralis muscle (Poland anomaly).

• Muscle surgery for esotropia: bilateral medial rectus recession.

• Treat exposure keratopathy due to facial nerve palsy (see Chapters 3 and 5).

Restrictive Strabismus

Various disorders that cause tethering of one or more extraocular muscles; restriction of eye movement in the direction of action of the affected muscle (these processes cause incomitant strabismus); positive forced ductions. Most commonly occurs in thyroid-related ophthalmopathy (see Chapter 1), also in orbital fractures (see Chapter 1), and congenital fibrosis syndrome.

Congenital Fibrosis Syndrome

Variable muscle restriction and fibrosis. Five types:

Generalized Fibrosis (Autosomal Dominant [AD] > Autosomal Recessive [AR] > Idiopathic)

Most severe form; all muscles in both eyes affected including levator (ptosis), inferior rectus usually affected the worst.

Congenital Fibrosis of Inferior Rectus (Sporadic or Familial)

Only inferior rectus affected.

Strabismus Fixus (Sporadic)

Horizontal muscles affected in both eyes; medial rectus more often than lateral rectus causing severe esotropia.

Vertical Retraction Syndrome

Vertical muscles affected in both eyes; superior rectus more often than inferior rectus causing restriction of downgaze.

Congenital Unilateral Fibrosis (sporadic)

All muscles affected in one eye causing enophthalmos and ptosis.

Nystagmus

Definition

Involuntary, rhythmic oscillation of eyes; may be horizontal, vertical, torsional, or a combination; fast or slow; symmetric or asymmetric; pendular (equal speed in both directions) or jerk (direction designated by the fast phase component).

Etiology

Congenital Nystagmus

Nystagmus is different depending on gaze; may have null point (nystagmus slows or stops in certain eye positions; usually 15 ° off center); one dominant locus; most cases occur independent of vision.

Afferent or sensory deprivation

Pendular or jerk nystagmus; due to visual dysfunction from ocular albinism, aniridia, achromatopsia, congenital stationary night blindness, congenital optic nerve anomaly, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, and congenital cataracts.

Efferent or motor

Usually horizontal nystagmus, but can be vertical, torsional or any combination; due to ocular motor disturbance; present at or shortly after birth, may be hereditary; mapped to chromosome 6p. Usually horizontal; may have null point and head turn (to move eyes to the null point); decreases with convergence and stops during sleep; no oscillopsia; may have head oscillations, a latent component, and inversion with horizontal optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) testing (60%); associated with strabismus (33%).

Latent

Bilateral jerk nystagmus when one eye is covered (jerk component away from covered eye) that resolves when eye is uncovered; may be associated with congenital esotropia and DVD; only present under monocular viewing conditions; therefore, binocular visual acuity is better than when each eye is tested separately; normal OKN response; may have a null point.

Spasmus nutans

Triad of nystagmus (monocular or asymmetric, fine, very rapid, horizontal, and variable), head nodding, and torticollis (head turning). Benign condition that develops between 4 and 12 months of age, disappears by 5 years of age; otherwise neurologically intact. Similar eye movements can occur with chiasmal gliomas and parasellar tumors; therefore, check pupils for relative afferent pupillary defect and optic nerve carefully and perform neuroimaging; spasmus nutans is a diagnosis of exclusion; monitor for amblyopia.

Acquired Nystagmus

Various types of nystagmus are localizing.

Convergence–retraction

Co-contraction of horizontal recti muscles causes jerk convergence–retraction of eyes on attempted upward saccade. Occurs in dorsal midbrain syndrome; classically associated with a pinealoma, but also with other neoplasms, trauma, stroke, or demyelination (multiple sclerosis).

Dissociated or disconjugate

Unilateral or asymmetric nystagmus; most commonly occurs in internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO).

Downbeat

Jerk nystagmus with rapid downbeat and slow upbeat; seen most easily in lateral and downgaze; null point is usually in upgaze. Associated with cervicomedullary junctional lesions including Arnold–Chiari malformation, syringomyelia, multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular accidents, and drug intoxication (lithium); may respond to clonazepam treatment.

Drug-induced

Associated with use of anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine), barbiturates, tranquilizers, and phenothiazines; often gaze-evoked; may be absent in downgaze.

Gaze-evoked

Jerk nystagmus in direction of gaze, no nystagmus in primary position; can be physiologic (fatigable with prolonged eccentric gaze, symmetric) or pathologic (prolonged, asymmetric); often due to medications (anticonvulsants, sedatives) or brain stem or posterior fossa lesions.

Periodic alternating

Very rare, horizontal jerk nystagmus present in primary gaze with spontaneous direction changes every 60 to 90 seconds, with periods as long as 10 to 15 seconds of no nystagmus; cycling persists despite fixating on targets. May be congenital or due to vestibulocerebellar disease; also associated with cervicomedullary junction lesions; may respond to treatment with baclofen.

See-saw

One eye rises and incyclotorts while other eye falls and excyclotorts, then the process alternates; may have INO. Most commonly occurs in conjunction with a suprasellar mass; also diencephalon lesions, after cerebrovascular accidents or trauma, or congenital.

Upbeat

Nystagmus occurs in primary position, and worsens in upgaze. Non-localizing, usually due to anterior vermis and lower brain stem lesion; also associated with Wernicke’s syndrome or drug intoxication.

Vestibular

Usually horizontal with rotary component (fast component toward normal side, slow component toward abnormal side); may have associated vertigo, tinnitus, and deafness; due to lesion of end organ, peripheral nerve (fixation dampens nystagmus), or central (fixation does not inhibit nystagmus).

Physiologic Nystagmus

Occurs normally in a variety of situations including eccentric gaze, OKN, caloric, rotational (VOR; vestibulo-ocular reflex), head shaking, pneumatic, compression, flash-induced, flicker-induced.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic, may have decreased vision, oscillopsia (in acquired nystagmus), and other neurologic deficits depending on etiology (e.g., reduced hearing, tinnitus, vertigo with vestibular nystagmus).

Signs

Variable decreased visual acuity, ocular oscillations; may have better near than distance visual acuity, head turn, other ocular or systemic pathology (e.g., aniridia, bilateral media opacities, macular scars, optic atrophy, foveal hypoplasia, and albinism) ![]() (see Video 2.1, Video 2.2, Video 2.3, Video 2.4).

(see Video 2.1, Video 2.2, Video 2.3, Video 2.4).

Differential Diagnosis

Other oscillations including square wave jerks, saccadic oscillations, ocular flutter, superior oblique myokymia, opsoclonus (rapid, unpredictable, multidirectional saccades; absent during sleep; associated with neuroblastoma or after postviral encephalopathies in children; occurs with visceral carcinomas in adults; also known as saccadomania), fixation instability, and voluntary flutter (usually hysterical or malingering; unable to sustain longer than 30 seconds; typically in horizontal plane with rapid back-to-back saccades; lid fluttering may be present); and disturbances of saccades (i.e., cerebellar ataxia) or smooth pursuit (i.e., Parkinson’s disease) ![]() (see Video 2.5, Video 2.6, Video 2.7, Video 2.8).

(see Video 2.5, Video 2.6, Video 2.7, Video 2.8).

Evaluation

• May require head CT scan or MRI to rule out intracranial process.

• May require neurology or neuro-ophthalmology consultation.

Prognosis

Usually benign; depends on etiology.

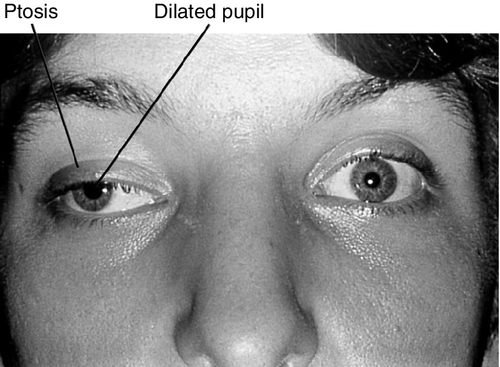

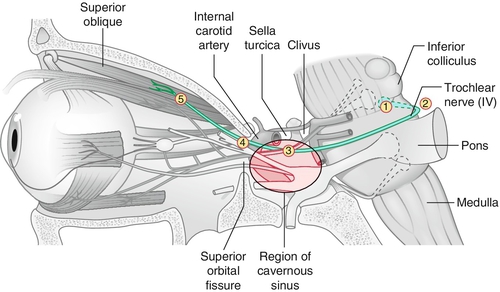

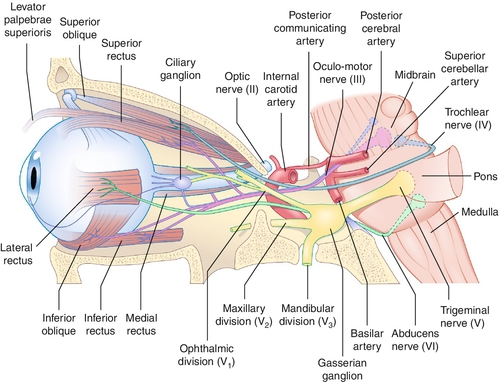

Third Cranial Nerve Palsy

Definition

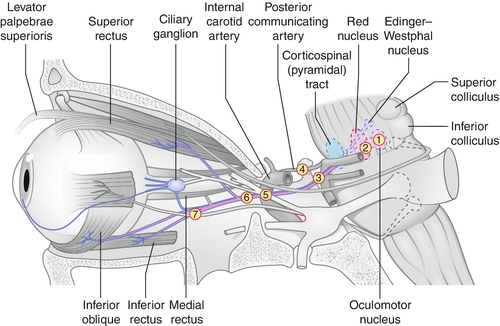

Paresis of CN III (oculomotor) caused by a variety of processes anywhere along its course from the midbrain to the orbit; can be complete or partial (superior division innervates superior rectus and levator; inferior division innervates medial rectus, inferior rectus, inferior oblique, and parasympathetic fibers to iris sphincter and ciliary muscle); can be isolated with or without pupil involvement.

Etiology

Depends on age: congenital due to birth trauma or neurologic syndrome; in children due to infection, postviral illness, trauma, or tumors (pontine glioma); in adults, most commonly due to ischemia or microvascular problems (20–45% hypertension or diabetes mellitus); also associated with aneurysm (15–20%), trauma (10–15%), and tumors (10–15%); 10–30% are of undetermined cause; rarely associated with ophthalmoplegic migraine. Aberrant regeneration suggests a compressive lesion such as an intracavernous aneurysm or tumor, though can also occur after trauma, but never after ischemic or microvascular causes; pupil sparing usually microvascular or ischemic (80% are pupil sparing); 95% of compressive lesions involve the pupil. Important to localize level of pathology:

Nuclear

Almost never occurs in isolation; usually due to microvascular infarctions; signs include bilateral ptosis and contralateral superior rectus involvement; also caused by more diffuse brainstem lesions (neoplasm, post-surgical), and other abnormalities are present.

Fascicular

Usually due to demyelinating vascular, or metastatic lesions; associated with several syndromes including Benedikt’s syndrome (CN III palsy with contralateral hemitremor, hemiballismus, and loss of sensation), Nothnagel’s syndrome (CN III palsy and ipsilateral cerebellar ataxia and dysmetria), Claude’s syndrome (combination of Benedikt’s and Nothnagel’s syndromes), and Weber’s syndrome (CN III palsy and contralateral hemiparesis).

Subarachnoid Space

Usually due to aneurysms (notably posterior communicating artery aneurysm), trauma, or uncal herniation; rarely microvascular disease or infections; pupil usually involved.

Intracavernous Space

Usually due to cavernous sinus fistula, aneurysms, tumors (e.g., lymphoproliferative), inflammation (e.g., Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, sarcoidosis), infections (e.g., herpes zoster, tuberculosis), or pituitary apoplexy; often associated with CN IV, V, and VI findings and sympathetic abnormalities (see Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies section); pupil usually spared (90%).

Orbital Space

Rare but may be due to neoplasm, trauma, or infections; often associated with CN II, IV, V, and VI findings (see Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies section); CN III splits before superior orbital fissure, so partial (superior or inferior division) palsies may occur (however, partial CN III palsies from fascicular and subarachnoid lesions may resemble divisional injury clinically).

Symptoms

Binocular diplopia (disappears with one eye closed), eye turn; may have pain, headache, ipsilateral droopy eyelid.

Signs

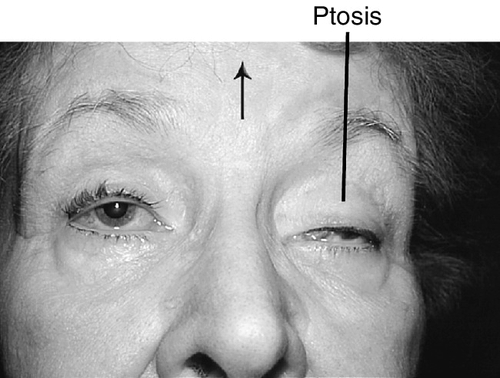

Ptosis, ophthalmoplegia except lateral gaze, torsion with attempted infraduction due to action of the trochlear nerve, negative forced ductions, exotropia and hypotropia in primary gaze (eye is down and out); may have mid-dilated nonreactive pupil (“blown” pupil, efferent defect); in cases of aberrant regeneration: lid-gaze dyskinesis (inferior rectus or medial rectus fibers to levator causing upper lid retraction on downgaze [pseudo-von Graefe’s sign] or on adduction), pupil-gaze dyskinesis (inferior rectus or medial rectus fibers to iris sphincter causing pupil constriction on downgaze or on adduction); may have other neurologic deficits or cranial nerve palsies ![]() (see Video 2.9).

(see Video 2.9).

Differential Diagnosis

Myasthenia gravis, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO).

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Fasting blood glucose, complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), and antinuclear antibody (ANA).

• Check blood pressure.

• MRI or magnetic resonance or computed tomography angiography (MRA, CTA), or both, if pupil involved in any patient, if associated with other neurologic abnormalities, if pupil spared in patients < 50 years old, if signs of aberrant regeneration are present, or if no improvement of isolated pupil-sparing microvascular cases after 3 months. Ninety percent sensitivity in aneurysms of 3 mm or greater in diameter, although the gold standard is digital substraction angiography (DSA) if tests are inconclusive.

• Consider lumbar puncture to assess for infection, cytology, or evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Neuro-ophthalmology or interventional neuroradiology consultation (especially if pupil involved).

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; complete or near-complete recovery expected with microvascular palsies, which tend to resolve within 2–3 months (6 months maximum). Worse for palsies due to trauma, or compressive lesions in which aberrant regeneration may develop.

Fourth Cranial Nerve Palsy

Definition

Paresis of CN IV (trochlear) caused by a variety of processes anywhere along its course from the midbrain to the orbit.

Etiology

Common causes include trauma (especially closed head trauma with contrecoup forces), microvascular disease (e.g., hypertension or diabetes mellitus), congenital (may or may not have head tilt), cavernous sinus disease (inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic), brain stem pathology (stroke, neoplasm), and rarely aneurysm. In roughly 30% no cause is identified; bilateral injury can occur with severe head trauma. Important to localize level of pathology:

Nuclear

Most often due to stroke, less often neoplasm, and almost never isolated; other causes include demyelinative disease and trauma.

Fascicular

Rare, same associations as nuclear; may get contralateral Horner’s syndrome; trauma (especially near anterior medullary velum) may cause bilateral CN IV palsies.

Subarachnoid Space

Usually due to closed head trauma; rarely tumor, infection, or aneurysm.

Intracavernous Space

Due to cavernous sinus disease from inflammation (sarcoidosis), infection (fungal), or neoplasm (lymphoproliferative, meningioma, pituitary macroadenoma); usually associated with CN III, V, and VI findings and sympathetic abnormalities (see Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies section).

Symptoms

Binocular vertical or oblique diplopia; may have torsional component, blurred vision, contralateral head tilt.

Signs

Superior oblique palsy with positive Parks–Bielschowsky three-step test (see below), ipsilateral hypertropia (greatest on contralateral gaze and ipsilateral head tilt), excyclotorsion (if > 10°, likely bilateral), large vertical fusional amplitude in congenital cases (> 4PD); chin-down position; negative forced ductions; bilateral cases have V-pattern esotropia, left hypertropia on right gaze, and right hypertropia on left gaze; other neurologic deficits if CN IV paresis is not isolated (see ![]() Video 2.10).

Video 2.10).

Differential Diagnosis

Myasthenia gravis, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, orbital disease, CN III palsy, Brown’s syndrome, and skew deviation.

Evaluation

Complete ophthalmic history, neurologic exam with attention to cranial nerves, and eye exam with attention to motility, head posture (check old photographs for longstanding head tilt in congenital cases), vertical fusion, double Maddox rod test (measure torsional component), and forced ductions.

• Perform Parks–Bielschowsky three-step test to determine paretic muscle:

• Step 2: Identify horizontal direction of gaze that makes the hypertropia worse (e.g., if left gaze then problem is with right superior oblique/inferior oblique or left superior rectus/inferior rectus).

• Step 3: Bielschowsky head-tilt test: identify direction of head tilt that makes the hypertropia worse (e.g., if right head tilt, then problem is with right superior oblique/superior rectus or left inferior oblique/inferior rectus).

After three steps, the paretic muscle will be identified (e.g., right hypertropia in primary position, worse on left gaze, and right head tilt indicates right superior oblique).

• Check blood pressure.

• Consider neuroimaging in unresolved cases and those with associated findings. CT scan may suffice if there is evidence of orbital disease; MRI for suspected intracranial pathology, and angiography (conventional, MRA or CTA) to assess for an aneurysm.

• Consider lumbar puncture.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Neuro-ophthalmology consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; complete or near-complete recovery is expected with microvascular palsies.

Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsy

Definition

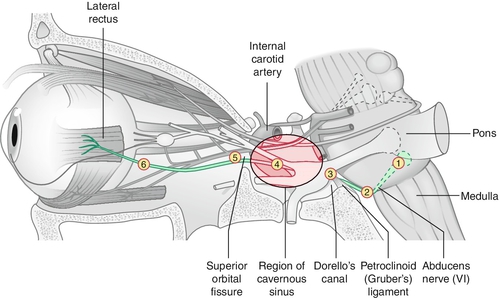

Paresis of CN VI (abducens) caused by a variety of processes anywhere along its course from the pons to the orbit.

Etiology

Depends on age: in children (< 15 years old) most commonly tumors (e.g., pontine glioma) or postviral; in young adults (15–40 years old) usually miscellaneous or undetermined (8–30%); in adults (> 40 years old) usually due to trauma or microvascular disease (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus [most common isolated cranial nerve palsy in diabetes: CN VI > III > IV]); also associated with multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular accidents, increased intracranial pressure, and, rarely, tumors (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma). Important to localize level of pathology:

Nuclear

Due to pontine infarcts, pontine gliomas, cerebellar tumors, microvascular disease, or Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome; causes an ipsilateral, horizontal gaze palsy (cannot look to side of lesion).

Fascicular

Usually due to tumors, microvascular disease, or demyelinating disease; can cause Foville’s syndrome (dorsal pons lesions with horizontal gaze palsy, ipsilateral CN V, VI, VII, VIII palsies, and ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome) and Millard–Gubler syndrome (ventral pons lesion with ipsilateral CN VI and VII palsies and contralateral hemiparesis).

Subarachnoid Space

Usually due to elevated intracranial pressure (30% of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension have CN VI palsy); also basilar tumors (e.g., acoustic neuroma, chordomas), basilar artery aneurysm, hemorrhage, inflammations, or meningeal infections.

Petrous Space

Due to trauma (e.g., basal skull fracture) or infections; Gradenigo’s syndrome (infection of petrous bone secondary to otitis media causing ipsilateral CN VI and VII paresis, ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, ipsilateral trigeminal pain, and ipsilateral deafness; occurs in children) or pseudo-Gradenigo’s syndrome (nasopharyngeal carcinoma may cause severe otitis media with findings similar to those of Gradenigo’s syndrome).

Intracavernous Space

Due to cavernous sinus disease from inflammation (sarcoidosis), infection (fungal), or neoplasm (lymphoproliferative, meningioma, pituitary macroadenoma); usually associated with CN III, V, and VI findings and sympathetic abnormalities (see Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies section).

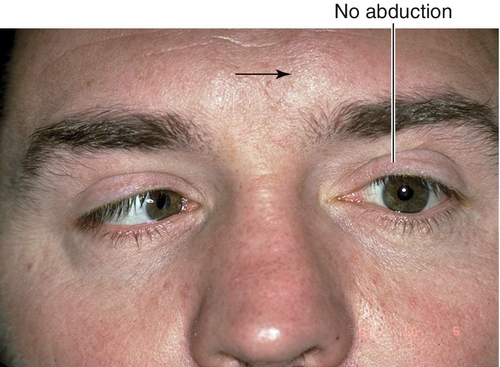

Symptoms

Horizontal binocular diplopia (worse at distance than near, and in direction of gaze of paretic muscle); may have eye turn.

Signs

Lateral rectus muscle palsy with esotropia and inability to abduct eye fully or slow abducting saccades; negative forced ductions; other neurologic deficits if CN VI paresis is not isolated (see ![]() Video 2.11).

Video 2.11).

Differential Diagnosis

Thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, myasthenia gravis, orbital inflammatory pseudotumor, Duane’s retraction syndrome type I, Möbius syndrome (CN VI and VII palsy), orbital fracture with medial rectus entrapment, spasm of near reflex.

Evaluation

• Observation for isolated cases in a patient with known vascular risk factors. If not resolved in 3 months individualized assessment is warranted; considerations include:

• Check blood pressure.

• Consider neuroimaging in nonresolving cases and those with associated findings. CT scan may suffice if there is evidence of orbital disease; MRI for suspected intracranial pathology, and angiography (conventional, MRA or CTA) to assess for an aneurysm.

• Consider lumbar puncture.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Neuro-ophthalmology consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; microvascular palsies tend to resolve within 3 months.

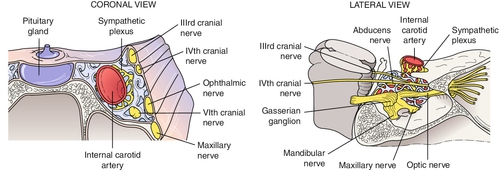

Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsies

Definition

Paresis of multiple cranial nerves appearing simultaneously; caused by a variety of processes anywhere along their courses from the brain stem to the orbits.

Etiology

Myasthenia gravis, Guillain–Barré syndrome (especially Miller–Fisher variant), Wernicke’s encephalopathy, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, stroke, multiple sclerosis, cavernous sinus/orbital apex or orbital disease.

Brain Stem

Due to midbrain or pons vascular lesions or tumors involving cranial nerve nuclei that are in close proximity.

Subarachnoid Space

Usually due to infiltrations, infections, or neoplasms.

Cavernous Sinus Syndrome

Multiple cranial nerve pareses (CN III, IV, V1, V2,VI) and sympathetic involvement due to parasellar lesions, which affect these motor nerves in various combinations in the sinus or superior orbital fissure; may have Horner’s syndrome due to oculosympathetic paresis; caused by aneurysms (e.g., intracavernous carotid artery), arteriovenous fistulas (e.g., carotid–cavernous fistula, dural sinus fistula), tumors (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, meningioma, pituitary adenoma, chordoma), inflammations (e.g., Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, Tolosa–Hunt syndrome), or infections (e.g., cavernous sinus thrombosis, herpes zoster, tuberculosis, syphilis, mucormycosis); lesions of the cavernous sinus do not necessarily affect all the cranial nerves in it.

Orbital Apex Syndrome

Multiple motor cranial nerve palsies and optic nerve (CN II) dysfunction; etiologies similar to those mentioned above.

Symptoms

Pain, diplopia; may have eye turn, droopy eyelid, variable decreased vision, and dyschromatopsia.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity and color vision (orbital apex syndrome), ptosis, strabismus, limitation of ocular motility, negative forced ductions, decreased facial sensation in CN V1–V2 distribution, relative afferent pupillary defect, miosis (Horner’s syndrome), and trigeminal (facial) pain; may have proptosis, conjunctival injection, chemosis, increased intraocular pressure, bruit, and retinopathy in cases of high-flow arteriovenous fistulas; fever, lid edema, and signs of facial infection in cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, myasthenia gravis, giant cell arteritis, Miller–Fisher variant of Guillain–Barré syndrome, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, orbital disease (see Chapter 1).

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Fasting blood glucose, CBC with differential, ESR, VDRL, FTA-ABS, ANA; consider blood cultures if infectious etiology suspected.

• Head, orbital, and sinus CT scan or MRI–MRA or both.

• Consider lumbar puncture.

• Consider cerebral angiography to rule out aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Neuro-ophthalmology, otolaryngology, or medical consultations as needed.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; usually poor.

Chronic Progressive External Ophthalmoplegia (CPEO)

Definition

Slowly progressive, bilateral, external ophthalmoplegia affecting all directions of gaze.

Etiology

Isolated or hereditary myopathy; several rare syndromes:

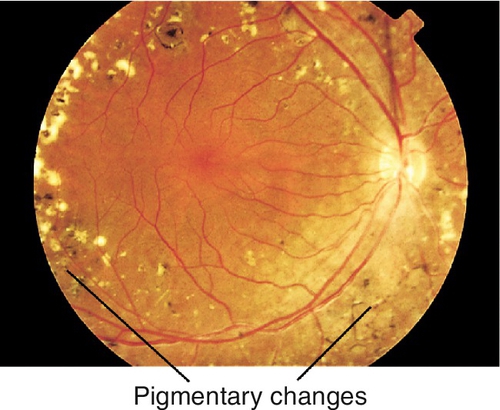

Kearns–Sayre Syndrome (Mitochondrial DNA)

Triad of CPEO, pigmentary retinopathy (see Chapter 10), and cardiac conduction defects (arrhythmias, heart block, cardiomyopathy); also associated with mental retardation, short stature, deafness, vestibular problems (ataxia), and elevated cerebrospinal fluid protein. Usually appears before age 20. Histology shows ragged red fibers.

• Genetics: Gene deletion in mitochondrial DNA impairs oxidative phosphorylation.

Mitochondrial Encephalopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-Like Episodes (Mitochondrial DNA)

Appears in childhood after normal development. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) may also have vomiting, seizures, hemiparesis, hearing loss, dementia, short stature, hemianopia, CPEO, optic neuropathy, pigmentary retinopathy, and cortical blindness. Stroke-like episodes begin before age 40.

Myoclonic Epilepsy and Ragged Red Fibers (Mitochondrial DNA)

Appear in childhood or adolescence. Encephalomyopathy with myoclonus, seizures, ataxia, spasticity, dementia, and ragged red fibers on muscle biopsy (Gomori trichrome stain) (MERRF); may also have dysarthria, optic neuropathy, nystagmus, short stature, and hearing loss.

• Genetics: More than 80% of cases are caused by mutations in MT-TK gene.

Myotonic Dystrophy (Autosomal Dominant)

Most common form of muscular dystrophy that begins in adulthood. CPEO, bilateral ptosis, lid lag, orbicularis oculi weakness, miotic pupils, “Christmas tree” (polychromic) cataracts, and pigmentary retinopathy with associated muscular dystrophy (worse in morning), cardiomyopathy, frontal baldness, temporalis muscle wasting, testicular atrophy, and mental retardation. Two major types (type 1 and type 2); signs and symptoms overlap, but type 2 tends to be milder than type 1.

Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy (Autosomal Dominant)

Occurs after age 40. CPEO with dysphagia. Common in French-Canadians; approximately 1 in 1000 individuals. Also more frequent in Bukharan (Central Asian) Jewish population of Israel, affecting 1 in 600.

• Genetics: Mutations in the PABPN1 gene on chromosome 14q11.

Symptoms

Variable decreased vision (if associated with a syndrome with retinal or optic nerve abnormality), droopy eyelids, foreign body sensation, tearing. Usually no diplopia, even with ocular misalignment.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, limitation of eye movements (even with doll’s head maneuvers and caloric stimulation), absent Bell’s phenomenon, often orthophoric (may develop strabismus, usually exotropia), negative forced ductions, ptosis, orbicularis oculi weakness, superficial punctate keratitis (especially inferiorly), cataracts, retinal pigment epithelial changes or pigmentary retinopathy (see Chapter 10); pupils usually spared.

Differential Diagnosis

Downgaze palsy (lesion of rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus [riMLF]), upgaze palsy, progressive supranuclear palsy, dorsal midbrain syndrome, myasthenia gravis.

Evaluation

• Consider muscle biopsy (deltoid) to check for abnormal “ragged red” muscle fibers or electromyography for definitive diagnosis.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Consider lumbar puncture.

• Medical consultation for complete cardiac evaluation including electrocardiogram (Kearns–Sayre syndrome, myotonic dystrophy) and swallowing studies (oculopharyngeal dystrophy).

• Mitochondrial DNA analysis for deletions for mitochondrial disorders.

Prognosis

Depends on syndrome; usually poor.

Horizontal Motility Disorders

Definition

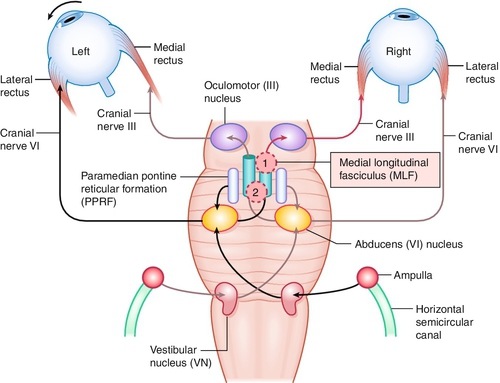

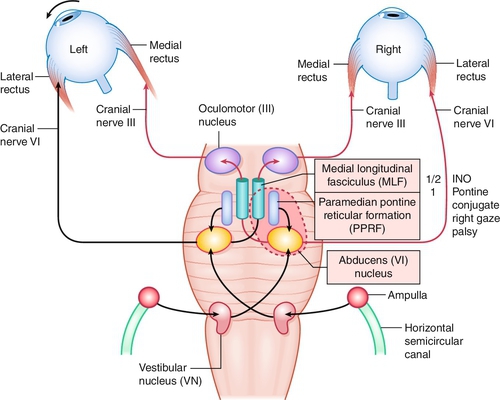

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia

Lesion of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), which traverses between the contralateral CN VI nucleus and the ipsilateral CN III subnucleus, serving the medial rectus muscle; results in an ipsilateral deficiency of adduction and contralateral abducting nystagmus; convergence can be absent (mesencephalic lesion; anterior lesion) but is usually intact (lesion posterior in the MLF); may be unilateral or bilateral (appears exotropic; WEBINO, “wall-eyed” bilateral INO).

One-and-a-Half Syndrome

So-called internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) plus with lesion of paramedian pontine reticular formation (PPRF; the horizontal gaze center) or CN VI nucleus, and the ipsilateral MLF causing conjugate gaze palsy to ipsilateral side (one) and INO or inability to adduct on gaze to contralateral side (half).

Other

Congenital (supranuclear or infranuclear) lesions of CN6 and interneurons, Möbius’ syndrome, ocular motor apraxia, frontoparietal lesions, parieto-occipital lesions, tegmental lesions, pontine lesions, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, drugs.

Etiology

Depends on age: less than 50 years old usually demyelinative (unilateral or bilateral INO) or tumor (pontine glioma for one-and-a-half syndrome); bilateral in children, often due to brain stem glioma; over 50 years old usually vascular disease; other causes include arteriovenous malformation, aneurysm, basilar artery occlusion, multiple sclerosis, or tumor (pontine metastasis).

Symptoms

Binocular horizontal diplopia worse in contralateral gaze.

Signs

Limitation of eye movements (cannot adduct on side of lesion in INO; can abduct only on side contralateral to lesion in one-and-a-half syndrome); nystagmus in abducting contralateral eye (INO); doll’s head maneuvers and caloric stimulation absent, negative forced ductions; may have upbeat nystagmus or skew deviation (involvement of nuclei rostral to the MLF) (see ![]() Video 2.12).

Video 2.12).

Differential Diagnosis

Medial rectus palsy, pseudo-gaze palsy (i.e., thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, myasthenia gravis, CPEO, orbital inflammatory pseudotumor, Duane’s syndrome, spasm of near reflex) (see ![]() Video 2.13).

Video 2.13).

Evaluation

• MRI with attention to brain stem and midbrain.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Consider neurology or neurosurgery consultation.

Prognosis

Usually good, with complete recovery in patients with a vascular lesion or demyelination. Permanent deficits develop in multiple sclerosis from repeated insults.

Vertical Motility Disorders

Definition

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (Steele–Richardson–Olszewski Syndrome)

Degenerative neurologic disorder with Parkinsonian features that causes progressive, bilateral, external ophthalmoplegia affecting all directions of gaze; usually starts with vertical gaze (downgaze first). Mapped to chromosome 17 (variant in gene for tau protein called the H1 haplotype).

Dorsal Midbrain (Parinaud’s) Syndrome

Caused by lesions of the upper brain stem. Findings include supranuclear palsy of vertical gaze (upgaze first). Results from injury to the dorsal midbrain, specifically, compression or ischemic damage of the mesencephalic tectum, including the superior colliculus adjacent oculomotor (origin of cranial nerve III) and Edinger–Westphal nuclei, causing motor dysfunction of the eye.

Skew Deviation

Comitant or incomitant acquired vertical misalignment of the eyes due to supranuclear dysfunction from posterior fossa process; hypotropic eye is ipsilateral to lesion; typically have other brainstem-related signs and symptoms.

Etiology

Dorsal Midbrain (Parinaud’s) Syndrome

Classically described with pineal tumors (in young men), also occurs with cerebrovascular accidents, hydrocephalus, arteriovenous malformation, trauma, multiple sclerosis, or syphilis.

Skew Deviation

Non-localizing but occurs most often with brain stem or cerebellar lesions.

Symptoms

Blurred vision, binocular diplopia (at near with dorsal midbrain syndrome); may have trouble reading, foreign body sensation, tearing, or dementia (progressive supranuclear palsy [PSP]), or other neurologic symptoms (skew deviation).

Signs

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (Steele–Richardson–Olszewski Syndrome)

Progressive limitation of voluntary eye movements (but doll’s head maneuvers give full range of motion), negative forced ductions; may have nuchal rigidity and seborrhea, progressive dementia, dysarthria, and hypometric saccades.

Dorsal Midbrain (Parinaud’s) Syndrome

Supranuclear paresis of upgaze (therefore vestibular, doll’s head maneuver, and Bell’s phenomenon intact), negative forced ductions, light-near dissociation; may have papilledema, convergence–retraction nystagmus (on attempted upgaze or downward OKN drum), lid retraction (Collier’s sign), spasm of convergence and accommodation (causing induced myopia), skew deviation, superficial punctate keratitis (especially inferiorly).

Skew Deviation

Vertical ocular misalignment (comitant or incomitant), hypotropic eye is ipsilateral to lesion, hypertropic eye is extorted and hypotropic eye is intorted (evident on fundoscopic examination); may have other neurologic signs.

Differential Diagnosis

Downgaze palsy (lesion of riMLF), upgaze palsy, CPEO, myasthenia gravis, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, oculogyric crisis (transient bilateral tonic supraduction of eyes and neck hyperextension; occurs in phenothiazine overdose and more rarely in Parkinson’s disease), Whipple’s disease, olivopontocerebellar atrophy, kernicterus.

Evaluation

• Head and orbital CT scan or MRI-MRA, or both, with attention to brain stem and midbrain.

• Consider edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test, ice pack test, or anti-ACh receptor antibody test to rule out myasthenia gravis.

• Consider neurology or neurosurgery consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

Myasthenia Gravis

Definition

Autoimmune disease of the neuromuscular junction causing muscle weakness; hallmark is variability and fatigability.

Etiology

Autoantibodies to acetylcholine receptors of striated muscles found in 70–90% of patients with generalized myasthenia, but is as low as 50% in purely ocular myasthenia; does not affect pupils or ciliary muscle. Increased frequency of HLA-B8 and DR3.

Epidemiology

Female predilection; positive family history in 5%; 90% have eye involvement (levator, orbicularis oculi, and extraocular muscles), 75% as initial manifestation, 20% ocular only; increased incidence of autoimmune thyroid disease, thymoma (10% with systemic and probably less in purely ocular myasthenia), scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, and thyroid-related ophthalmopathy.

Symptoms

Binocular diplopia, droopy eyelids, dysarthria, dysphagia; all symptoms are more severe when tired or fatigued.

Signs

Variable, asymmetric ptosis (worse with fatigue, sustained upgaze, and at end of day), variable limitation of extraocular movements (mimics any motility disturbance), negative forced ductions, strabismus, orbicularis oculi weakness; Cogan’s lid twitch (upper eyelid twitch when patient looks up to primary position after looking down for 10–15 seconds); rarely gaze-evoked nystagmus; very rarely may resemble an INO (see ![]() Video 2.14).

Video 2.14).

Differential Diagnosis

Gaze palsy, multiple sclerosis, CN III, IV, or VI palsy, INO, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, CPEO, idiopathic orbital inflammation, and levator dehiscence.

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Anti-ACh receptor antibodies, thyroid function tests (T3, T4, TSH, TSI).

• Ice pack test: ptosis improves after ice or cold pack applied to eyelids for 2 minutes.

• Edrophonium chloride (Tensilon) test: Test dose of edrophonium chloride 2 mg IV with 1 mL saline flush, then observe for improvement in diplopia and lid signs over next minute; if no improvement, increase edrophonium chloride dose to 4 mg IV with 1 mL saline flush and observe for improvement in diplopia and lid signs; repeat two times; if no improvement in diplopia and lid signs after 3 to 4 minutes, the test result is negative; a negative test result does not rule out myasthenia gravis. Note: consider cardiac monitoring in at-risk patients because of cardiovascular effects of edrophonium chloride; if bradycardia, angina, or bronchospasm develop, inject atropine (0.4 mg IV) immediately; consider pretreating with atropine 0.4 mg IV.

• Consider single-fiber electromyography of peripheral or orbicularis muscles for definitive diagnosis.

• Chest CT scan to rule out thymoma.

• Neurology or medical consultation or both.

Prognosis

Variable, chronic, progressive; good if ocular only.