59

Oral Diseases

Common Oral Mucosal Findings

Fordyce Granules

Geographic Tongue (Migratory Glossitis)

• Well-demarcated areas of erythema and atrophy of the filiform papillae, surrounded by a whitish, hyperkeratotic serpiginous border (Fig. 59.1); lesions tend to migrate over time, may affect other oral sites, and are occasionally associated with a burning sensation.

Scrotal (Fissured) Tongue

Hairy Tongue (Black Hairy Tongue)

• Confluence of hairlike projections, which represent elongated papillae, with yellowish to brown-black discoloration (Fig. 59.3); may have exogenous staining from food, tobacco, or chromogenic bacteria (especially following antibiotic therapy); some patients report an unpleasant odor or taste.

Fig. 59.3 Hairy tongue. The dorsum of the tongue exhibits marked accumulation of keratin and brown discoloration. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• DDx: pigmented papillae of the tongue (in individuals with darkly pigmented skin).

Leukoedema

Median Rhomboid Glossitis

• Found in ~1% of adults, often associated with local overgrowth of Candida.

• Well-demarcated diamond- or oval-shaped area of erythema and atrophy on the dorsum of the tongue (Fig. 59.4).

Fig. 59.4 Median rhomboid glossitis. On the dorsum of the tongue (anterior to the circumvallate papillae), there is a well-demarcated, smooth area with loss of the filiform papillae.

• Rx: clotrimazole troches or oral fluconazole (for dosage, see Table 64.5).

Periodontal and Dental Conditions with Dermatologic Relevance

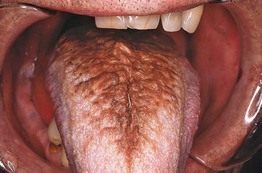

Desquamative Gingivitis

• Clinical finding that can occur in several immune-mediated vesicular and erosive disorders (Fig. 59.5); favors women over 40 years of age.

Fig. 59.5 Differential diagnosis of desquamative gingivitis. If the gingivae are painful, hemorrhagic, and necrotic with punched-out interdental papillae, then necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (trench mouth) should also be considered. *No cutaneous lesions present. **Erythema multiforme is more likely to affect other mucosal sites. BP, bullous pemphigoid; EBA, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita; LABD, linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• Diffuse gingival erythema with varying degrees of sloughing and erosion; frequently painful.

• Because desquamative gingivitis is often a manifestation of mucous membrane (cicatricial) pemphigoid and other autoimmune bullous disorders, evaluation should include routine histology plus direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies (see Chapter 23).

• Rx: treatment of underlying condition plus meticulous oral hygiene.

Gingival Enlargement (Hyperplasia, Overgrowth)

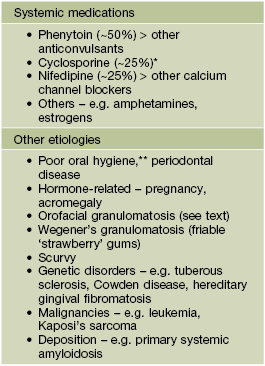

• Systemic medications and other causes of gingival enlargement are listed in Table 59.2.

Table 59.2

Causes of gingival enlargement.

Another term for Wegener’s granulomatosis is granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s).

* Consider substitution with oral tacrolimus.

** Often contributes to gingival enlargement related to drugs and other factors.

Dental Sinus

• Occurs in the setting of a chronic periapical abscess in a carious tooth.

• Cutaneous: erythematous papule, often with an umbilicated or ulcerated center; found on the chin or submandibular region (mandibular teeth) > the cheek or upper lip (maxillary teeth) (Fig. 59.6).

Fig. 59.6 Cutaneous sinuses of dental origin. These skin lesions can be associated with mandibular (A) or, less often, maxillary (B) teeth. The erythematous papule may be mistaken for a pyogenic granuloma or neoplasm. A, Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD; B, Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

Sequelae of Trauma or Toxic Insults

Fibroma (Bite Fibroma)

Morsicatio Buccarum (Chronic Cheek Chewing)

• Characteristic mucosal changes related to habitual chewing or biting.

• Shaggy white mucosa, usually bilaterally in the buccal region along the ‘bite line’ (Fig. 59.7).

Fig. 59.7 Cheek chewing (morsicatio buccarum). Repetitive nibbling of the superficial layers of the epithelium resulted in these changes. Note that the characteristic shaggy, white lesion approximates the area where the upper and lower teeth meet. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

Mucocele

• Translucent to bluish papule due to disruption of a minor salivary gland duct, most often located on the lower mucosal lip (Fig. 59.8; see Chapter 90).

Chemotherapy- and Radiation Therapy-Induced Mucositis

Cheilitis

• The differential diagnosis of cheilitis and clues to determining the etiology are outlined in Fig. 13.5; granulomatous cheilitis is discussed below.

• Cheilitis glandularis, seen primarily in men with a history of chronic sun exposure and/or lip irritation, is characterized by inflammatory hyperplasia of the lower labial salivary glands; this results in tiny erythematous macules (at sites of salivary ducts) and variable hypertrophy of the lower lip (Fig. 59.9).

Other Inflammatory Conditions

Aphthae (Aphthous Stomatitis; Canker Sores)

• Minor aphthae (most frequent form): painful, round to ovoid, shallow ulcers that are usually <5 mm in diameter; feature a yellowish-white to gray pseudomembranous base, well-defined border, and prominent erythematous rim (Fig. 59.10); favor the buccal or labial mucosa and typically heal in 1–2 weeks without scarring.

Fig. 59.10 Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Shallow, creamy-white ulceration surrounded by an intensely red halo and located on nonkeratinized mucosa, representing a classic presentation. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• Complex aphthosis: frequent outbreaks of multiple (≥3) oral aphthae, or recurrent genital as well as oral aphthae, in the absence of Behçet’s disease (see Chapter 21).

• Recurrent aphthae can occur in the setting of systemic disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease, SLE, and Behçet’s disease (see Table 59.1).

• DDx: in addition to associated systemic conditions, may include HSV infection, trauma, and the disorders listed in Fig. 59.5.

• Rx: superpotent topical CS gel, topical analgesics; if severe or frequent recurrences: vitamin B12, colchicine, dapsone, thalidomide (the latter is especially helpful for major aphthae).

Granulomatous Cheilitis and Other Forms of Orofacial Granulomatosis

• The term orofacial granulomatosis refers to non-infectious, non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the lips, face, and/or oral cavity; this term includes isolated granulomatous cheilitis as well as manifestations of Crohn’s disease and sarcoidosis (see Table 59.1); usually develops during the second or third decade of life.

• Granulomatous cheilitis presents as diffuse swelling of the lip(s) (lower > upper or both) that can initially be intermittent (raising the possibility of angioedema) but is eventually persistent (Fig. 59.11); patients may have oral cobblestoning, recurrent aphthae, and gingival enlargement, and the less frequent association with a scrotal tongue and/or facial nerve palsy is referred to as Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome.

Contact Stomatitis

• Shaggy white or erythematous areas, most often on the buccal mucosa or lateral tongue; lacy white streaks (resembling lichen planus) or erosions may be seen (Fig. 59.12).

Nicotine Stomatitis

• Presents as gray-white discoloration of the palate, often with umbilicated papules that represent inflamed salivary ducts (Fig. 59.13).

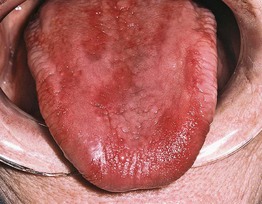

Atrophic Glossitis

• Manifestation of several nutritional deficiencies (e.g. vitamin B12 [pernicious anemia], folate, iron, niacin [pellagra], riboflavin; see Chapter 43) and candidiasis.

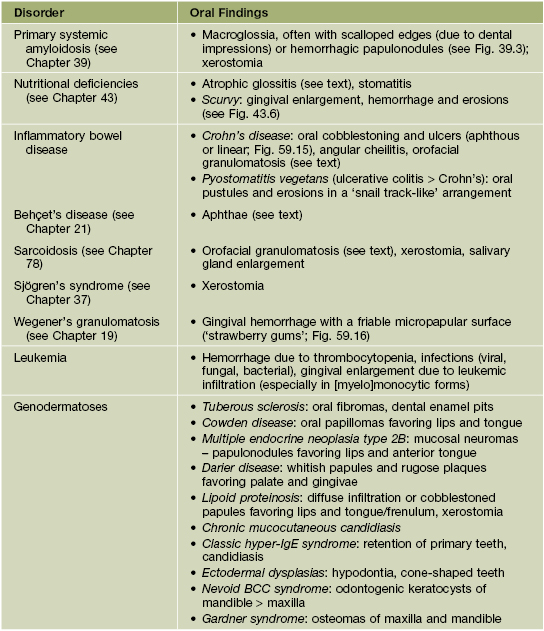

• Presents with a smooth, ‘beefy red’ tongue (Fig. 59.14); involvement may initially be patchy but is eventually diffuse and may be associated with a burning sensation or sore mouth.

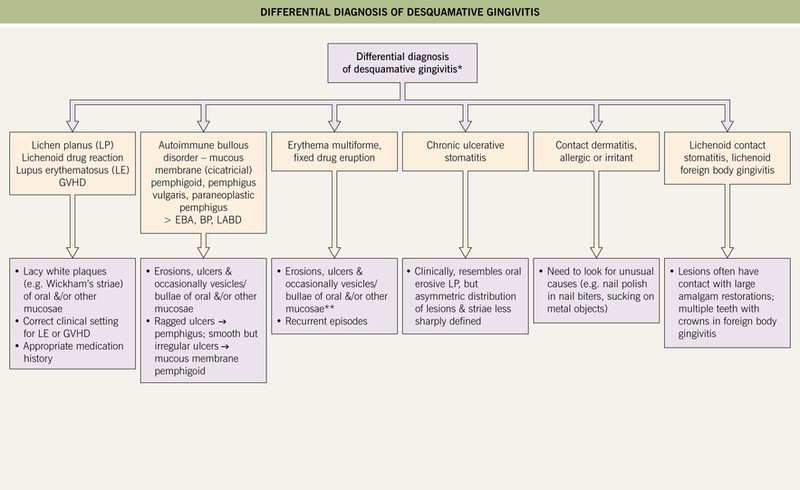

Oral Signs of Systemic Disease

• Systemic diseases that can present with oral findings are listed in Table 59.1 (Figs. 59.15 and 59.16).

Fig. 59.15 Crohn’s disease. Linear ulceration of the mandibular vestibule is the classic oral manifestation of this disease. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

Premalignant and Malignant Conditions

Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia

• Leukoplakia refers to a white patch or plaque on the oral mucosa that cannot be clinicopathologically characterized as a specific disease process; typically occurs in middle-aged and older adults (men > women), especially those who use tobacco ± alcohol, and is regarded as a premalignant condition for SCC.

– Often a homogeneous white patch or plaque, but may be nonhomogeneous and ‘speckled’ (e.g. white flecks on a red base); usually has sharply demarcated borders (Fig. 59.17).

Fig. 59.17 Leukoplakia. Sharply demarcated, white plaque involving the ventral surface of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• Similarly, erythroplakia is defined as a red intraoral patch or slightly elevated, velvety plaque that cannot be diagnosed as a particular disease; biopsies usually show more severe epithelial dysplasia than leukoplakia.

• Often affects the buccal mucosa, lower inner lip, floor of the mouth, and lateral or ventral tongue.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

• Most common malignancy of the oral cavity, favoring middle-aged and older men; risk factors include tobacco and alcohol use, HPV infection (see Chapter 66), and betel nut chewing.

• May present as an ulcer, exophytic mass, or area of induration; most often on the lateral or ventral tongue and floor of the mouth (Fig. 59.18).

Fig. 59.18 Squamous cell carcinoma. Ulcerated, indurated, exophytic mass involving the right lateral border of the tongue, a typical presentation and site for this tumor. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• DDx: leukoplakia, traumatic ulcer (Fig. 59.19), salivary gland tumor, amelanotic melanoma.

Fig. 59.19 Traumatic ulcer. This lesion on the lateral tongue has a yellow fibrinopurulent membrane and white hyperkeratotic border. Compare this to the oral SCC depicted in Fig. 59.18, which presented as an ulcerated, indurated mass. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

• Rx: combinations of surgery, radiation therapy (especially if HPV-associated), and chemotherapy.

Melanoma

• Pigmented (with findings similar to cutaneous melanoma; see Chapter 93) > amelanotic, with a predilection for the hard palate and maxillary gingivae.

• DDx: for pigmented lesions – foreign body tattoo (Fig. 59.20), blue nevus, oral melanotic macule, physiologic pigmentation.

Fig. 59.20 Amalgam tattoo. Foreign body tattoos are the most common cause of acquired oral pigmentation, and most of them are due to implantation of dental amalgam. In this patient, the amalgam was used to seal the apices of endodontically treated teeth, resulting in tattooing of the maxillary vestibule. Courtesy, Carl M. Allen, MD, and Charles Camisa, MD.

For further information see Ch. 72. From Dermatology, Third Edition.