Chapter 53

Oral Anticoagulation

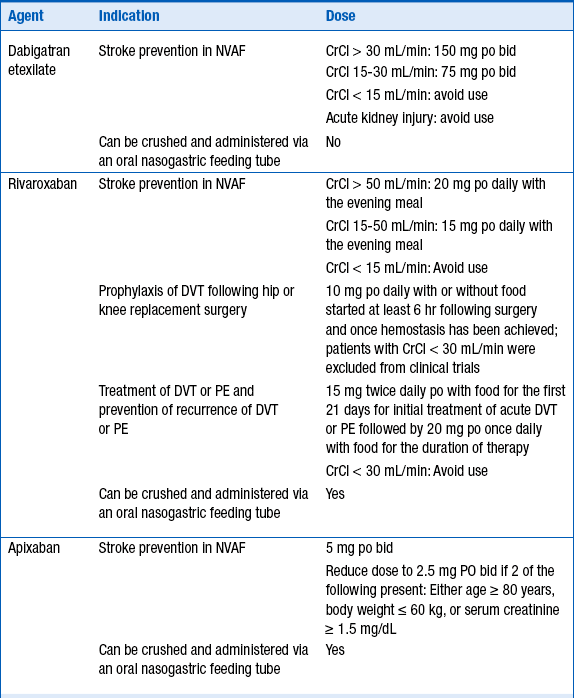

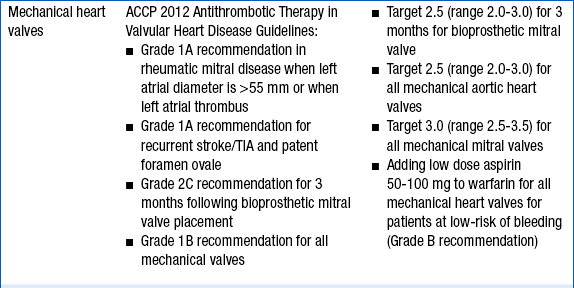

2. What are the clinical situations in which warfarin is used and at what anticoagulation intensity?

The intensity of anticoagulation with warfarin depends primarily on the indication for anticoagulation. These are given in Table 53-1.

TABLE 53-1

INDICATIONS FOR ANTICOAGULATION WITH WARFARIN AND RECOMMENDED INTERNATIONAL NORMALIZED RATIO INTENSITY

3. What is the role of warfarin in preventing transient ischemic attack and stroke in a patient with a history of ischemic stroke?

4. How should unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux be overlapped with warfarin for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism?

Regardless of the parenteral agent chosen for initial anticoagulation, warfarin should be initiated on day 1 of treatment. Choice of dose must be individualized based on patient-specific factors (age, concurrent medications, nutrition status, and comorbidities). However, for most patients, 5 mg daily is an adequate starting dose. According to the ACCP’s Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th edition, for younger, “healthier” patients, consideration may be given for initiating warfarin at 10 mg daily. UFH, LMWH, or fondaparinux should be overlapped with warfarin for a minimum of 4 to 5 days and until the international normalized ratio (INR) is therapeutic (INR more than 2.5 for 1 day, or more than 2.0 for 2 consecutive days). Recommended procedures for switching between warfarin and the newer oral anticoagulants dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are reviewed in Question 14.

5. What is the role of pharmacogenomics in warfarin dosing?

6. How should warfarin be managed in patients who need surgery?

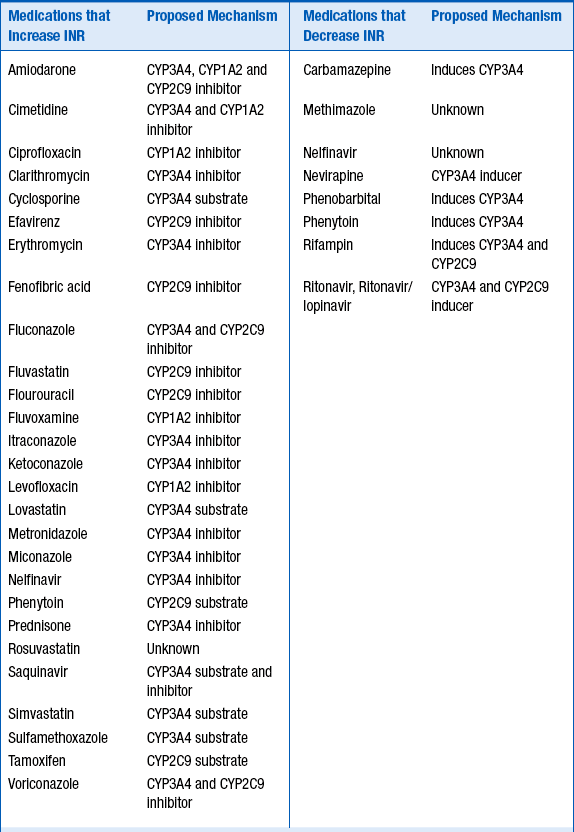

7. What are some of the common drug interactions with warfarin?

Because of its complex metabolism and relatively narrow therapeutic index, drug interactions involving warfarin are both common and clinically significant. The majority of the interactions occur at the level of CYP metabolism, although other mechanisms may be possible. Table 53-2 lists some of the more common interactions.

TABLE 53-2

COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED MEDICATIONS THAT INCREASE OR DECREASE WARFARIN’S INTERNATIONAL NORMALIZED RATIO

For the medications listed in Table 53-2, the strength of the clinical evidence is sufficient to expect a change in INR, requiring either adjusting the warfarin dose up or down by 25% to 50% in anticipation of the resulting change in INR, or frequent INR monitoring to determine the dose adjustment necessary.

Foods and supplements may also alter the INR. Foods that increase the INR include garlic, mango, ginseng, grapefruit juice, and possibly cranberry juice. Ginger and fish oil have additive antithrombotic effects. Foods and supplements that reduce the INR include high vitamin K–content foods, enteral feeds, and soy milk.

8. How should warfarin be managed in patients with underlying chronic liver disease?

9. How should elevated INRs in patients taking warfarin be managed?

10. What are important patient counseling points for warfarin?

Explain to patients the reason for warfarin therapy.

Explain to patients the reason for warfarin therapy.

Explain the meaning and significance of the INR.

Explain the meaning and significance of the INR.

Identify each patient’s warfarin prescriber, current INR, and date of next scheduled INR test.

Identify each patient’s warfarin prescriber, current INR, and date of next scheduled INR test.

Explain the need for frequent INR testing and the target INR for each patient’s medical condition(s).

Explain the need for frequent INR testing and the target INR for each patient’s medical condition(s).

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy and related laboratory work (INR checks).

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy and related laboratory work (INR checks).

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and to report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and to report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Explain how consuming foods containing vitamin K may impact the effectiveness of warfarin therapy and that the most important thing concerning the diet is not to make any significant changes without talking to the health care provider.

Explain how consuming foods containing vitamin K may impact the effectiveness of warfarin therapy and that the most important thing concerning the diet is not to make any significant changes without talking to the health care provider.

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that warfarin is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing warfarin needs to be informed of all scenarios where warfarin might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that warfarin is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing warfarin needs to be informed of all scenarios where warfarin might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain to patients the importance of contacting the pharmacy if the color of the warfarin tablet is different.

Explain to patients the importance of contacting the pharmacy if the color of the warfarin tablet is different.

Explain that warfarin should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed and it is within 12 hours of when the dose was supposed to be taken, it is okay to take the dose. Otherwise, the dose should be skipped and resumed the next day. The dose should not be doubled.

Explain that warfarin should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed and it is within 12 hours of when the dose was supposed to be taken, it is okay to take the dose. Otherwise, the dose should be skipped and resumed the next day. The dose should not be doubled.

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their warfarin prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication (especially antibiotics).

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their warfarin prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication (especially antibiotics).

Explain that women of child-bearing age must use birth control measures and notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Explain that women of child-bearing age must use birth control measures and notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking warfarin.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking warfarin.

Depending on the indication for warfarin, counsel patients on signs of clotting (e.g., calf pain, redness, swelling, shortness of breath, and stroke symptoms).

Depending on the indication for warfarin, counsel patients on signs of clotting (e.g., calf pain, redness, swelling, shortness of breath, and stroke symptoms).

11. What are potential advantages of the newer oral anticoagulants dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban?

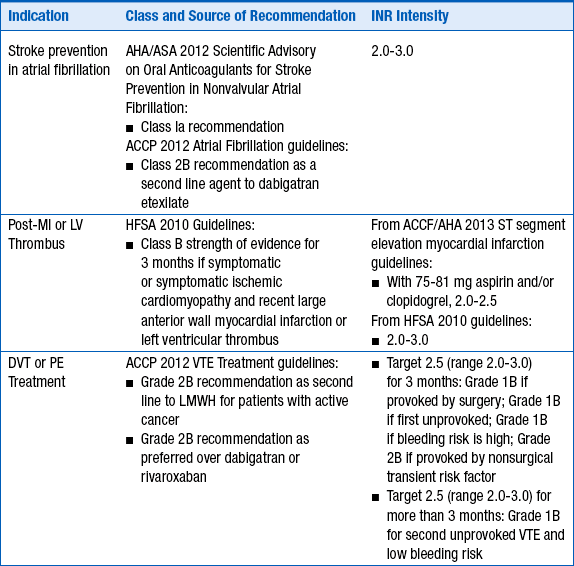

Dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are three newer oral anticoagulants which offer the following advantages over warfarin: quick onset of anticoagulant effects, no need for bridging, fewer drug interactions, and no routine anticoagulation monitoring. Dabigatran etexilate is an oral direct thrombin (factor IIa) inhibitor that is a prodrug hydrolyzed after absorption to form dabigatran, the active agent. Dabigatran is primarily eliminated renally (80%). Apixaban is a direct-acting factor Xa inhibitor that is renally excreted (27%) and hepatically metabolized (25% primarily by CYP3A4). Rivaroxaban is a direct-acting factor Xa inhibitor that is both metabolized (51% primarily by CYP3A4/5) and eliminated renally (36%). Dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are substrates for the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp), also known as multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) or ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1). As of this writing, dabigatran etexilate and rivaroxaban are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and rivaroxaban is FDA-approved for DVT prevention following hip and knee replacement surgery, for stroke prevention in NVAF, and treatment of DVT and pulmonary embolism. Dosing recommendations are described in Table 53-3. These newer anticoagulants should be avoided in patients with moderate to severe hepatic disease or in patients with hepatic disease showing signs of coagulopathy.

12. What are current guideline recommendations for dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban in U.S. practice guidelines for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?

Two current practice guidelines are available for management of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF), the 2012 ACCP guidelines and the 2012 AHA/American Stroke Association (ASA) guidelines. The 2012 ACCP guidelines do not include rivaroxaban or apixaban because they were not FDA-approved for stroke prevention in NVAF at the time of guideline writing. The 2012 ACCP guidelines recommend oral anticoagulation over aspirin in patients with a CHADS2 score (see Fig. 34-1 and Table 34-1) of 2 or greater, and in particular, recommend dabigatran over warfarin anticoagulation. This recommendation is based on the results of a large randomized clinical trial showing that there are fewer strokes and intracranial hemorrhages with dabigatran, as well as similar rates of major bleeding and slightly higher gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran compared to warfarin. The 2012 AHA/ASA Science Advisory gives class I recommendations to warfarin, dabigatran, and apixaban for stroke prevention in AF in patients with at least one risk factor for stroke and to rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in AF in patients with at least two risk factors for stroke. The 2012 AHA/ASA Science Advisory recommends against using either dabigatran or rivaroxaban in patients with creatine clearance of less than 15 mL/min and against using apixaban in patients with creatinine clearance of less than 25 mL/min. Rivaroxaban was found to be noninferior to warfarin for both stroke prevention and major bleeding, but demonstrated a reduction in the frequency of intracranial hemorrhage in its large phase III randomized double-blind clinical trial in NVAF. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin for stroke prevention (for both ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage reduction) with similar major bleeding rates in its large Phase III open-label trial in NVAF. Apixaban demonstrated superiority in stroke prevention, reduction in intracranial hemorrhage risk and major bleeding, along with a reduction in total mortality in its Phase III randomized double blind trial compared to warfarin in NVAF. In another randomized, double-blind Phase III trial in patients with NVAF unsuitable for warfarin, apixaban reduced stroke with similar major bleeding compared to aspirin.

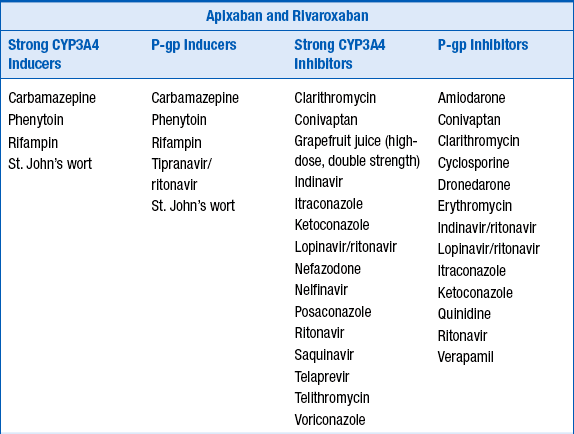

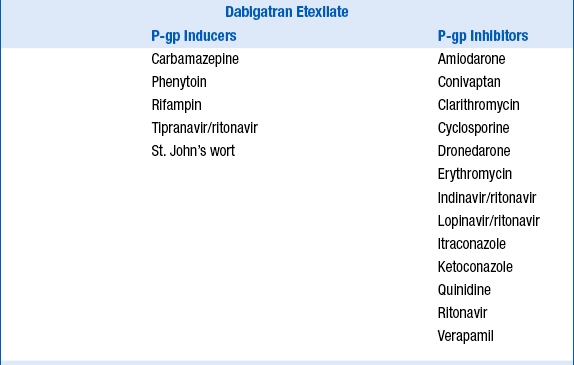

13. What are some of the common drug interactions with dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban?

Because dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are P-glycoprotein 1 (P-gp) substrates, apixaban a substrate for CYP3A4, and rivaroxaban a substrate for CYP3A4/5, their serum concentrations may be increased by P-gp inhibitors, and apixaban and rivaroxaban concentrations increased by CYP3A4 inhibitors. Potential drug interactions and labeled warnings are listed in Table 53-4. Dabigatran etexilate should not be coadministered with P-gp inhibitors in patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. A dose reduction in dabigatran etexilate to 75 mg orally twice daily is recommended for patients with creatinine clearance less of 30 to 50 mL/min who are also taking dronedarone or systemic ketoconazole. Rifampin, a strong P-gp inducer should be avoided with dabigatran. Combined use of strong CYP3A4 inhibitors and P-gp inhibitors is contraindicated with rivaroxaban. The dose of apixaban should be reduced to 2.5 mg twice daily when it is coadministered with combined strong CYP3A4 and P-gp inhibitors such as ketoconaole, itraconazole, ritonavir, and clarithromycin. For patients initially prescribed apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, combined use of strong dual CYP3A4 and P-gp inhibitors necessitates apixaban discontinuation and selection of another anticoagulant. Combined use of strong CYP3A4 inducers and P-gp inducers, such as rifampin, should be avoided with rivaroxaban and apixaban. Examples are provided in Table 53-4.

TABLE 53-4

POTENTIAL DRUG INTERACTIONS WITH DABIGATRAN ETEXILATE, APIXABAN, AND RIVAROXABAN WHICH INCREASE OR DECREASE THEIR CONCENTRATIONS

14. How should patients taking dabigatran etexilate, apixiban, or rivaroxaban be transitioned to and from other anticoagulants?

One of the major advantages of the newer oral anticoagulants is their rapid onset and offset of effect. The onset of anticoagulant effect with dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban is rapid. Peak concentration, and thus complete anticoagulant effect for dabigatran etexilate, is achieved in 1 hour in the fasting state and by 2 hours following a meal, in 2 to 3 hours following apixaban, and in 2 to 4 hours following rivaroxaban. Recommendations for switching between warfarin and either dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban as well as between an injectable anticoagulant are described in Table 53-5. For patients discontinuing dabigatran, these recommendations include monitoring renal function, as drug clearance (and thus clearance of anticoagulant effect) is delayed in patients with acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease. Switching between rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran has not been studied, but practicality indicates that first doses may be administered at the time the dose of the discontinued agent would be administered.

TABLE 53-5

CONVERTING FROM OR TO PARENTERAL ANTICOAGULANTS AND WARFARIN WITH DABIGATRAN ETEXILATE, APIXABAN, AND RIVAROXABAN

| Switching From | Switching to | Recommendation |

| Unfractionated heparin | Dabigatran etexilate | Give first dose at time heparin is discontinued. |

| Rivaroxaban | Give first dose at time heparin is discontinued. | |

| Apixaban | Give first dose at time heparin is discontinued. | |

| LMWH | Dabigatran etexilate | Give first dose at time next LMWH dose is due. |

| Rivaroxaban | Give first dose at time next LMWH dose is due. | |

| Apixaban | Give first dose at time next LMWH dose is due. | |

| Warfarin | Dabigatran etexilate | Monitor INR; start dabigatran when INR < 2.0. |

| Rivaroxaban | Monitor INR; start rivaroxaban when INR < 3.0. | |

| Apixaban | Monitor INR; start apixaban when INR < 2.0. | |

| Dabigatran etexilate | Unfractionated heparin | For CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min start UFH 12 hours after last dose dabigatran. For CrCl < 30 mL/min, start UFH 24 hours after last dose of dabigatran. |

| LMWH | For CrCl ≥ 30 mL/min give first injection 12 hours after last dose dabigatran. For CrCl < 30 mL/min, give first injection 24 hours after last dose of dabigatran. |

|

| Warfarin | For CrCl ≥ 50 mL/min – start warfarin 3 days before discontinuing dabigatran. For CrCl 30-50 mL/min – start warfarin 2 days before discontinuing dabigatran. For CrCl 15-30 mL/min – start warfarin 1 day before discontinuing dabigatran. |

|

| Rivaroxaban | Not studied; give first dose at the time of the next scheduled dabigatran dose. | |

| Apixaban | Give first dose at the time of the next scheduled dabigatran dose. | |

| Rivaroxaban | Unfractionated heparin | Start UFH at time of the next scheduled rivaroxaban dose. |

| LMWH | Give first injection at the time of the next scheduled rivaroxaban dose. | |

| Warfarin | Use parenteral anticoagulant bridge. | |

| Dabigatran etexilate | Give first dose at the time of the next scheduled rivaroxaban dose. | |

| Apixaban | Give first dose at the time of the next scheduled rivaroxaban dose. | |

| Apixaban | Unfractionated heparin | Start UFH at the time of the next scheduled apixaban dose. |

| LMWH | Give first injection at the time of the next scheduled apixaban dose. | |

| Warfarin | Use parenteral anticoagulation bridge. | |

| Dabigatran etexilate | Give first dose at the time of the next scheduled apixaban dose. | |

| Rivaroxaban | Give first dose at the time of the next scheduled apixaban dose. |

15. What is the effect of dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban on coagulation tests and can they be monitored?

16. Can the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, and rivaroxaban be reversed?

At this time, there is insufficient data and experience to recommend any methods of reversing the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, or rivaroxaban. Administration of activated charcoal is recommended if less than 2 hours has passed since the anticoagulant has been ingested. Hemodialysis removes about 60% of dabigatran over a 2 to 3 hour dialysis session and should be initiated immediately for life-threatening bleeding in a patient with recent dabigatran exposure. Administration of fresh frozen plasma alone is ineffective and not recommended. A four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) containing clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X, has shown reversal of prolonged PTs in healthy volunteers given rivaroxaban, and in animal models with dabigatran. However, the only available PCC in the U.S. at this time is a three-factor PCC, which has a lower concentration of factor VII. Recombinant factor VIIa (rVIIa) administration has demonstrated partial reversal of thrombin generation due to rivaroxaban in an in vitro model but does not reverse the effects of dabigatran. Low-dose anticoagulant inhibitor complex (factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity FEIBA NF; Baxter Bioscience, Deerfield, Ill.) has demonstrated reversal of endogenous thrombin potential, maximum concentration, lag-time, and time to reach maximum concentration of thrombin after both dabigatran and rivaroxaban administration in an ex vivo healthy volunteer study. However, higher doses of FEIBA increased thrombin generation in this study, and administration of any clotting factor heightens all thromboembolic risk, so the best advice in the case of significant bleeding associated with any of the new oral anticoagulants is to discontinue the anticoagulant and consult with a hematology anticoagulation specialist.

17. What are the important counseling points for patients taking dabigatran etexilate?

Explain to patients that dabigatran is being taken for stroke prevention in NVAF.

Explain to patients that dabigatran is being taken for stroke prevention in NVAF.

Explain that dabigatran etexilate may cause gastrointestinal upset and that if it occurs, patients may take the medication with food to minimize effect.

Explain that dabigatran etexilate may cause gastrointestinal upset and that if it occurs, patients may take the medication with food to minimize effect.

For patients with a prior history of taking warfarin, explain that dabigatran may affect the INR blood test, but that test is not used for monitoring the level of anticoagulation.

For patients with a prior history of taking warfarin, explain that dabigatran may affect the INR blood test, but that test is not used for monitoring the level of anticoagulation.

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy.

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy.

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and to report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and to report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that dabigatran etexilate is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing dabigatran needs to be informed of all scenarios where dabigatran might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that dabigatran etexilate is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing dabigatran needs to be informed of all scenarios where dabigatran might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain that dabigatran should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed and it is within 6 hours of when the dose was supposed to be taken, it is okay to take the dose. Otherwise, the dose should be skipped. The dose should not be doubled.

Explain that dabigatran should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed and it is within 6 hours of when the dose was supposed to be taken, it is okay to take the dose. Otherwise, the dose should be skipped. The dose should not be doubled.

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their dabigatran prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication. Avoid taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, including aspirin, with dabigatran.

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their dabigatran prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication. Avoid taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, including aspirin, with dabigatran.

Discuss the need for periodic monitoring of blood tests for kidney function.

Discuss the need for periodic monitoring of blood tests for kidney function.

Women of child-bearing age must notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Women of child-bearing age must notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking dabigatran etexilate.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking dabigatran etexilate.

Advise each patient to date the bottle label when opening, and to discard any unused capsules after 4 months.

Advise each patient to date the bottle label when opening, and to discard any unused capsules after 4 months.

18. What are the important counseling points for patients taking apixaban and rivaroxaban?

Explain to patients the reason that apixaban or rivaroxaban is being taken.

Explain to patients the reason that apixaban or rivaroxaban is being taken.

For patients with a prior history of taking warfarin, explain that may affect the PT/INR blood test, but the test is not used for monitoring the level of anticoagulation.

For patients with a prior history of taking warfarin, explain that may affect the PT/INR blood test, but the test is not used for monitoring the level of anticoagulation.

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy.

Explain the importance of compliance with therapy.

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and should report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Describe common sites and signs of bleeding and what to do if they occur. Explain that bleeding and bruising are more likely to occur and that common sites of bleeding include the gums, urinary tract, and nose. Patients should be aware of any changes in stool color and should report dark, tarry stools to the health care provider immediately. Patients should also report any uncontrolled bleeding to the health care provider.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Counsel patients to avoid alcohol and activities or sports that may result in a fall or injury.

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that apixaban or rivaroxaban is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing rivaroxaban needs to be informed of all scenarios where rivaroxaban might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain to patients the importance of telling all health care providers that apixaban or rivaroxaban is being taken and that the health care provider prescribing rivaroxaban needs to be informed of all scenarios where rivaroxaban might need to be held (e.g., dental work, surgery, and other invasive procedures).

Explain that apixaban or rivaroxaban should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed it may be taken on the same day as soon as it is remembered, otherwise resume the medication the next day.

Explain that apixaban or rivaroxaban should be taken at the same time each day and that if a dose is missed it may be taken on the same day as soon as it is remembered, otherwise resume the medication the next day.

Explain that doses of rivaroxaban 15 mg or 20 mg must be taken with a meal and that doses of 10 mg may be taken without regard to meals. Apixaban may be taken with or without food.

Explain that doses of rivaroxaban 15 mg or 20 mg must be taken with a meal and that doses of 10 mg may be taken without regard to meals. Apixaban may be taken with or without food.

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their apixaban or rivaroxaban prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication. Avoid taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, including aspirin, with either apixaban or rivaroxaban.

Discuss potential drug interactions. Explain that patients should contact their apixaban or rivaroxaban prescriber before taking any over-the-counter medications (including herbal supplements) or if a different health care provider starts them on a new medication. Avoid taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, including aspirin, with either apixaban or rivaroxaban.

Discuss the need for periodic monitoring of blood tests for kidney function.

Discuss the need for periodic monitoring of blood tests for kidney function.

Women of child-bearing age must notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Women of child-bearing age must notify their health care provider immediately if they become pregnant.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking rivaroxaban.

Advise patients to carry identification noting that they are taking rivaroxaban.

Depending on the indication apixaban or for rivaroxaban, counsel patients on signs of clotting (e.g., calf pain, redness, swelling, shortness of breath, or stroke symptoms).

Depending on the indication apixaban or for rivaroxaban, counsel patients on signs of clotting (e.g., calf pain, redness, swelling, shortness of breath, or stroke symptoms).

Document that the patient education session has occurred.

Document that the patient education session has occurred.

For acute treatment of VTE, counsel the patient that the initial rivaroxaban dose of 15 mg twice daily will need to be reduced to 20 mg once daily after 21 days of treatment.

For acute treatment of VTE, counsel the patient that the initial rivaroxaban dose of 15 mg twice daily will need to be reduced to 20 mg once daily after 21 days of treatment.

Patient information and resources for the prescriber, including discount.

Patient information and resources for the prescriber, including discount.

19. What is the safety of using combination antiplatelet therapy in a patient requiring warfarin, dabigatran etexilate, apixaban, or rivaroxaban as well?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Blood thinner pills: your guide to using them safely. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/consumer/btpills.htm. Accessed Sep 10, 2012

2. Bonow, R.O., Carabello, B.A., Chatterjee, K., et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;118:e523–e661.

3. Dewilde, W.J.M., Oirbans, T., Verheugt, F.W.A., et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised controlled trial, Lancet. published online February 13, 2013. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62177-1. Accessed March 4, 2013

4. Douketis, J.D., Spyropoulos, A.C., Spencer, F.A., et al, Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(Suppl 2):e326S–e350S Erratum in: Chest 2012 141 1129

5. Eerenberg, E.S., Kamphuisen, P.W., Sijpkens, M.K., et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–1579.

6. Eliquis (apixaban) prescribing information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, December 2012.

7. European Medicines Agency: Questions and answers on the review of bleeding risk with Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate). Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Medicine_QA/2012/05/WC500127768.pdf. Accessed Sep 10, 2012

8. Faxon, D.P., Eikelboom, J.W., Berger, P.B., et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary stenting: a North American perspective: executive summary. Circ Cardiovasc Interven. 2011;4:522–534.

9. Furie, K.L., Goldstein, L.B., Albers, G.W., et al. Oral antithrombotic agents for prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a science advisory for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:3442–3453.

10. Guyatt, G.H., Akl, E.A., Crowther, M., et al. Executive summary: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):7S–47S.

11. Kaatz, M., Kouides, P.A., Garcia, D.A. Guidance on the emergent reversal of oral thrombin and factor Xa inhibitors. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:S141–S145.

12. Kearon, C., Akl, A.L., Comorota, A.J., et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):e419S–e494S.

13. Lansberg, M.G., O’Donnell, M.J., Khatri, P., et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):e601–e636S.

14. Lindenfeld, J., Albert, N.M., Boehmer, J.P., et al. HFSA 2010 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2010;16:e1–e194.

15. Marlu, R., Enkelejda, H., Paris, A., et al. Effect of non-specific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:217–224.

16. O’Gara, P.T., Kushner, F.G., Ascheim, D.D., et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;61:e78–140.

17. Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate) prescribing information. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2012.

18. Samama, M.M., Contact, G., Spiro, T.E., et al. Evaluation of the anti-factor Xa chromogenic assay for the measurement of rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls. Thromb Haemostas. 2012;107:379–387.

19. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Drug development and drug interactions: table of substrates, inhibitors and inducers. Available at http://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/druginteractionslabeling/ucm093664.htm#inhibitors. Accessed Sep 10, 2012

20. Whitlock, R.P., Sun, J.C., Fremes, S.E., et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):e576S–e600S.

21. You, J.J., Singer, D.E., Lane, D.A., et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, ed 9: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):e531S–e575S.

22. Xarelto (rivaroxaban) prescribing information. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, March, 2013.