11

Optic Nerve and Glaucoma

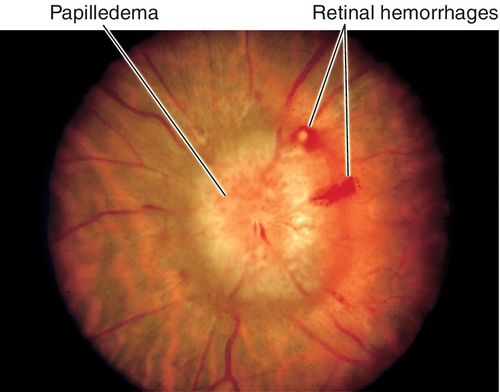

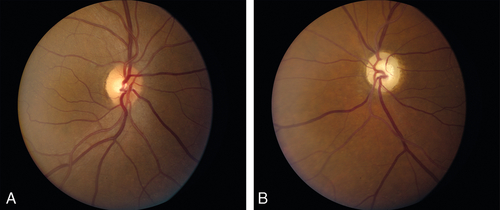

Papilledema

Definition

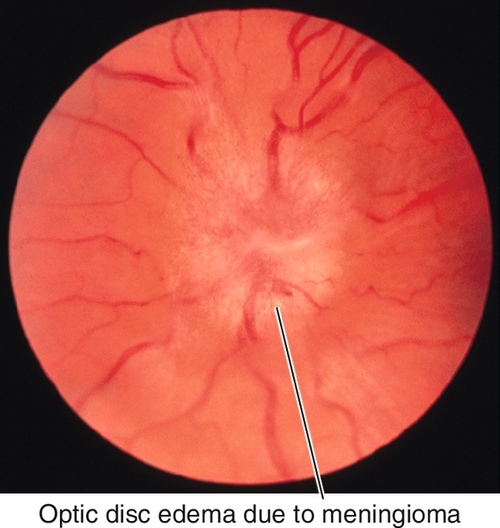

Optic disc swelling caused by elevated intracranial pressure (ICP).

Etiology

Elevated ICP occurs in a variety of settings including: congenitally; with intracranial neoplasm or other mass; infection (meningitis, encephalitis); or subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Often no cause is identified (idiopathic intracranial hypertension or pseudotumor cerebri; see below).

Symptoms

Initially asymptomatic, visual loss, and dyschromatopsia occur with chronic papilledema; may have headache, nausea, emesis, transient visual obscurations (lasting seconds), diplopia, altered mental status, or other neurologic deficits.

Signs

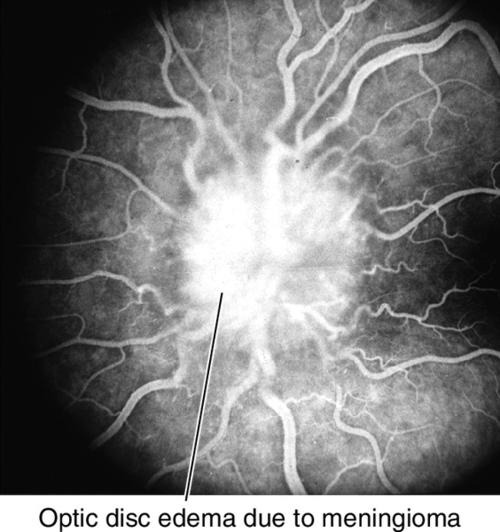

Normal or decreased visual acuity and color vision, red desaturation, enlarged blind spot proportional to degree of edema, bilateral (rarely unilateral) optic disc edema with blurred disc margins, disc hyperemia, reduced physiologic cup, thickened nerve fiber layer obscuring retinal vessels, peripapillary nerve fiber layer hemorrhages, cotton-wool spots, exudates, retinal folds (Paton’s lines), and absent venous pulsations (absent in 20% of normal individuals); may have cranial nerve VI palsy, vascular attenuation, visual field defects, decreased visual acuity and optic atrophy (occurs late with axonal loss). Foster–Kennedy syndrome refers to the finding of unilateral papilledema with contralateral optic atrophy and anosmia, due to an olfactory groove meningioma resulting in compression on one side (atrophy) and elevated ICP causing edema of the other disc.

Differential Diagnosis

Optic disc edema without elevated ICP is due to malignant hypertension, diabetic papillitis, anemia, central retinal vein occlusion, neuroretinitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, Leber’s optic neuropathy, hypotony, infiltration (lymphoma, leukemia), optic nerve mass, pseudopapilledema (e.g., optic nerve drusen).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

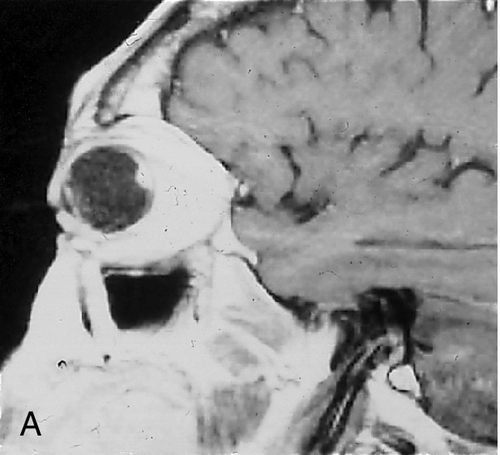

• Emergent neuroimaging: Head and orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (or CT scan if MRI not available) to rule out intracranial processes; consider venography (MRV) to look for venous sinus thrombosis.

• Lumbar puncture (after MRI) to check opening pressure and composition of cerebrospinal fluid.

• Lab tests: To identify etiology of disc edema if ICP is not elevated on LP. Fasting blood sugar, complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE).

• Check blood pressure.

• Neurology consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (Pseudotumor Cerebri)

Definition

Disorder of unknown etiology that meets the following criteria: (1) signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, (2) high cerebrospinal fluid pressure (> 200 mmH2O in nonobese and > 250 mmH2O in obese patients) with normal composition, (3) normal neuroimaging studies, (4) normal neurologic examination findings (except papilledema or cranial nerve VI palsy), and (5) no identifiable cause, such as an inciting medication (modified Dandy criteria).

Etiology

Idiopathic; may be associated with vitamin A, tetracycline, oral contraceptive pills (due to hypercoagulability and dural sinus thrombosis), nalidixic acid, lithium, or steroid use or withdrawal; also associated with dural sinus thrombosis, radical neck surgery, middle ear disease (which may cause dural sinus thrombosis), recent weight gain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pregnancy. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Epidemiology

Usually occurs in obese 20–45-year-old females (2 : 1).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have headache, transient visual obscurations (lasting seconds), intracranial noises (whooshing), diplopia, pulsatile tinnitus, dizziness, nausea, and emesis.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, color vision, and contrast sensitivity; bilateral optic disc edema; may have cranial nerve VI palsy (30%) or visual field defect.

Differential Diagnosis

Rule out other causes of papilledema and optic disc edema (see Papilledema section).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields (enlarged blind spot, generalized constriction).

• Emergent neuroimaging: Head and orbital MRI (or CT scan if MRI not available) to rule out intracranial processes; consider venography (MRV) to look for venous sinus thrombosis.

• Lumbar puncture (after MRI) to check opening pressure and composition of cerebrospinal fluid.

• Check blood pressure.

• Neurology consultation.

Prognosis

Usually self-limited over 6–12 months; variable if visual loss has occurred.

Optic Neuritis

Definition

The term optic neuritis refers to inflammation of the optic nerve.

Papillitis

Inflammation is anterior, optic disc swelling present.

Retrobulbar

Inflammation is behind the globe, no optic disc swelling; more common.

Devic’s Syndrome

Bilateral optic neuritis with transverse myelitis.

Etiology

Demyelination is the most common cause; others include vasculitic, infectious, and autoimmune.

Epidemiology

Demyelinative optic neuritis usually occurs in 15–45-year-old females. The majority of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have evidence of optic neuritis; this approaches 100% in postmortem pathologic studies; optic neuritis is the initial diagnosis in 20% of MS cases; conversely, roughly 50–60% of patients with isolated optic neuritis will eventually develop MS. Note: optic neuritis in children is usually bilateral, postviral (i.e., mumps, measles), and less likely to be associated with MS.

Symptoms

Subacute visual loss (usually progresses for 1–2 weeks followed by recovery over the following 3 months), pain on eye movement, dyschromatopsia, diminished sense of brightness; may have previous viral syndrome, or phosphenes (light flashes) on eye movement or with loud noises.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity ranging from 20/ 20 to no light perception, visual field defect (most often central or paracentral scotoma, but any pattern of field loss can occur), decreased color vision and contrast sensitivity, relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD); may have optic disc swelling (35%), mild vitritis, altered depth perception (Pulfrich’s phenomenon), and increased latency and decreased amplitude of visual evoked response.

Differential Diagnosis

Intraocular inflammation, malignant hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cat-scratch disease, optic perineuritis, sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, collagen vascular disease, Leber’s optic neuropathy, optic nerve glioma, orbital tumor, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, central serous retinopathy, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome, acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement syndrome.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• If patient does not carry the diagnosis of MS, then obtain an MRI of the head and orbits to evaluate periventricular white matter for demyelinating lesions or plaques (best predictor of future development of MS).

• Lab tests: Unnecessary for typical case of optic neuritis. When atypical features exist: ANA, ACE, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, ESR; consider Bartonella henselae if optic nerve is swollen and exposure to kittens.

• Check blood pressure.

• Consider lumbar puncture to rule out intracranial processes.

• Neuro-ophthalmology consultation.

Prognosis

Good in cases of demyelination; visual acuity improves over months; final acuity depends on severity of initial visual loss; 70% of patients will recover 20 / 20 vision. Permanent subtle color vision and contrast sensitivity deficits are common; even after recovery, patient may have blurred vision with increased body temperature or exercise (Uhthoff’s phenomenon or symptom). Approximately 30% will have another attack in either eye, and 30–50% of patients with isolated optic neuritis will develop MS over 5–10 years.

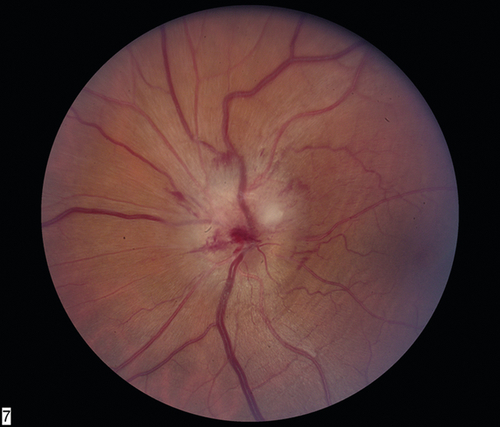

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

Definition

Ischemic infarction of anterior optic nerve due to occlusion of the posterior ciliary circulation just behind the lamina cribrosa.

Etiology

Optic nerve infarction is encountered in different settings, but is often divided into two categories:

Arteritic

Occurs in the setting of giant cell arteritis (GCA; temporal arteritis).

Nonarteritic

Occurs in several settings but is most often “spontaneous” without an identified precipitating factor.

Epidemiology

Arteritic

Usually occurs in patients > 55 years old (mostly over 70), the fellow eye is involved in 75% of cases within 2 weeks without treatment; associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.

Nonarteritic

Usually occurs in middle-aged patients; fellow eye is involved in up to 40% of cases. Associated with hypertension (40%), diabetes mellitus (30%), ischemic heart disease (20%), hypercholesterolemia (70%), and smoking (50%); arteriosclerotic changes are found in optic disc vessels.

Symptoms

Acute, unilateral, painless visual loss (arteritic > nonarteritic) and dyschromatopsia.

Arteritic

May also have headache, fever, malaise, weight loss, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, amaurosis fugax, diplopia, polymyalgia rheumatica symptoms (joint pain), and eye pain.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, decreased color vision, RAPD, central or altitudinal visual field defect (usually inferior and large), swollen optic disc (pallor or atrophy after 6–8 weeks), fellow nerve often crowded with a small or absent cup, fellow nerve may be pale from prior episode (pseudo Foster–Kennedy syndrome; more common than true Foster–Kennedy [see above]).

Arteritic

May also have swollen, tender, temporal artery, cotton-wool spots, branch or central retinal artery occlusion, ophthalmic artery occlusion, anterior segment ischemia, cranial nerve palsy (especially cranial nerve VI); optic disc cupping occurs late; choroidal infarcts can be seen on fluorescein angiogram.

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant hypertension, diabetes mellitus, retinal vascular occlusion, compressive lesion, collagen vascular disease, syphilis, herpes zoster; also migraine, postoperative, massive blood loss, normal (low)-tension glaucoma.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, color vision, Amsler grid, pupils, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Check visual fields.

• Lab tests: STAT ESR (to rule out arteritic form; ESR > [age/ 2] in men and > [(age 10)/2] in women is abnormal), CBC (low hematocrit, high platelets), fasting blood glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), VDRL, FTA-ABS, ANA.

• Check blood pressure.

• Arteritic: Consider temporal artery biopsy (beware: can get false-negative results from skip lesions); will remain positive up to 2 weeks after starting corticosteroids.

• Consider fluorescein angiogram; choroidal nonperfusion in arteritic form.

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Worse for the arteritic form associated with GCA in which visual recovery is rare. Roughly 10% with the nonarteritic form will progress and slightly more than 42% will improve (≥ 3 Snellen lines, but some of this perceived improvement may represent learning to scan with the remaining visual field as opposed to true axonal recovery).

Traumatic Optic Neuropathy

Definition

Damage to the optic nerve (intraocular, intraorbital, or intracranial) from direct or indirect trauma.

Etiology

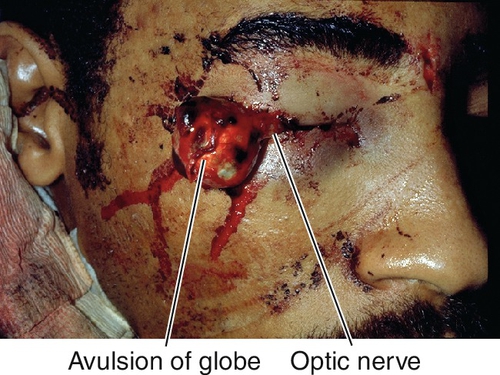

Direct Injuries

Orbital or cerebral trauma that transgresses normal tissue planes to disrupt the anatomic integrity of the optic nerve (e.g., penetrating injury or bone fragment).

Indirect Injuries

Forces transmitted at a distance from the optic nerve; the mechanism of injury may involve transmission of energy through the cranium, resulting in elastic deformation of the sphenoid bone, and thus a direct transfer of force to the canalicular portion of the nerve.

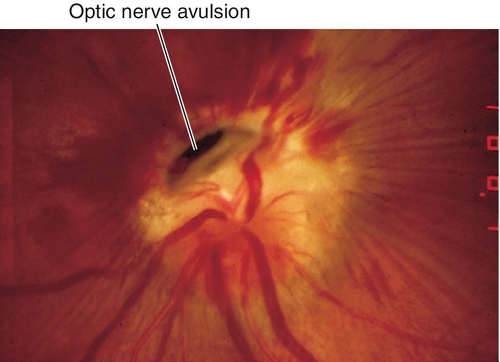

Optic Nerve Avulsion

Dislocation of the nerve at its point of attachment with the globe; usually occurs with deceleration injuries causing anterior displacement of the globe.

Epidemiology

Occurs in 3% of patients with severe head trauma and 2.5% of patients with midfacial fractures.

Symptoms

Acute visual loss, dyschromatopsia, pain from associated injuries.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity ranging from 20 / 20 to no light perception, RAPD, decreased color vision, visual field defect; optic nerve usually appears normal acutely with optic atrophy developing later; may have other signs of ocular trauma. Hemorrhage at the location of the optic disc occurs with optic nerve avulsion.

Differential Diagnosis

Commotio, open globe, retinal detachment, Terson’s syndrome, Purtscher’s retinopathy, macular hole, vitreous hemorrhage.

Evaluation

• Check for associated life-threatening injuries.

• Complete ophthalmic history, neurologic exam, and eye exam with attention to mechanism of injury, visual acuity, color vision, pupils, motility, tonometry, anterior segment, and ophthalmoscopy.

• Orbital CT scan with thin coronal images through the canal to assess location and extent of damage, mechanism of injury, and associated trauma.

• Check visual fields.

• Medical or neurology consultation may be required for associated injuries.

Prognosis

Usually poor, depends on degree of optic nerve damage; 20–35% improve spontaneously.

Other Optic Neuropathies

Definition

Variety of processes that cause unilateral or bilateral optic nerve damage and subsequent optic atrophy. Atrophy of axons with resultant disc pallor occurs 6–8 weeks after injury anterior to the lateral geniculate nucleus.

Etiology

Compressive

Neoplasm (orbit, suprasellar), thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, hematoma.

Hereditary

Isolated

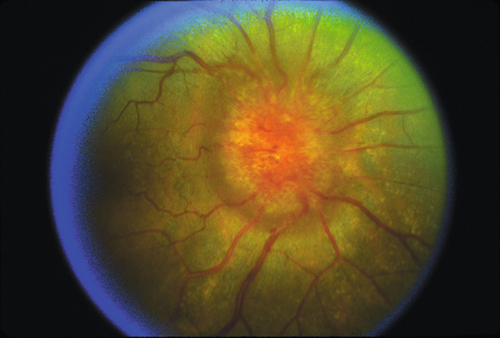

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy

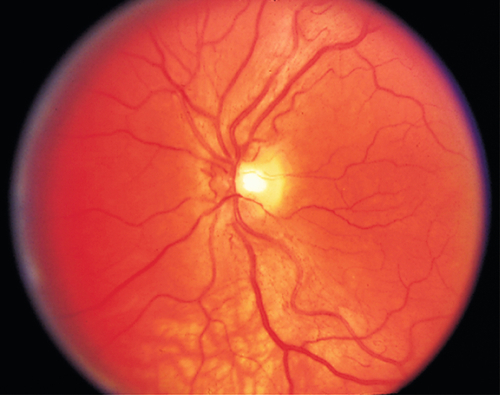

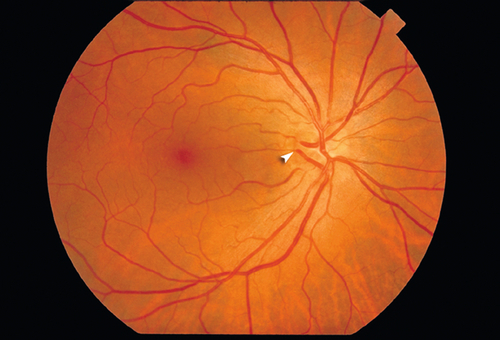

Typically occurs in 10- to 30-year-old males (9 : 1). Rapid, severe visual loss that starts unilaterally, but sequentially involves fellow eye usually within 1 year but can be within days to weeks. Optic nerve hyperemia and swollen nerve fiber layer with small, peripapillary, telangiectatic blood vessels that do not leak on fluorescein angiography (optic nerve also does not stain). Mitochondrial DNA mutation – mothers transmit defect to all sons (50% affected) and all daughters are carriers (10% affected). Three common mutations in the mitochondrial genome at nucleotide positions 3460, 11778, and 14484 have been identified.

Dominant optic atrophy (Kjer or juvenile optic atrophy)

Most common hereditary optic neuropathy, prevalence of 1 : 12,000 to 1 : 50,000; highly variable age of onset (mean around 4 to 6 years of age). Mild, insidious loss of vision (ranging from 20 / 20 to 20 / 800), tritanopic dyschromatopsia; slight progression; nystagmus rare; a wedge of pallor is seen on the temporal aspect of the disc (temporal excavation). Mapped to chromosomes 3q28-q29 (OPA1 gene), 18q12.2-q12.3 (OPA4 gene), and 22q12-q13 (OPA5 gene).

Other

• Recessive optic atrophy (Costeff syndrome): Mapped to OPA6 gene on chromosome 8q21-q22.

• X-linked optic atrophy: Mapped to OPA2 gene on chromosome Xp11.4-p11.2.

With syndrome

Diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness; early onset, rapid progression. Mitochondrial DNA inheritance; mapped to chromosome 4p16.1 (WFS1 gene) and 4q22-q24 (WFS2 gene).

Complicated hereditary infantile optic atrophy (Behr’s syndrome)

Occurs between 1 and 8 years of age; male predilection. Moderate visual loss; no progression; associated with nystagmus in 50%, increased deep tendon reflexes, spasticity, hypotonia, ataxia, urinary incontinence, pes cavus, and mental retardation. Mapped to chromosome 19q13 (OPA3 gene).

Other

Various syndromic hereditary optic neuropathies often with deafness and other systemic findings.

Infectious

Toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, cytomegalovirus, tuberculosis.

Infiltrative

Sarcoidosis, malignancy (lymphoma, leukemia, carcinoma, plasmacytoma, metastasis).

Ischemic

Radiation.

Nutritional

Various vitamin deficiencies including B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B6 (pyridoxine), B12 (cobalamin), and folic acid.

Toxic

Most commonly due to ethambutol; rarer causes include isoniazid, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, arsenic, lead, methanol, digitalis, chloroquine, quinine, and tobacco-related or alcohol-related amblyopia.

There are anecdotal reports of an ischemic-like optic neuropathy occurring with the use of erectile dysfunction drugs (i.e., sildenafil, vardenafil, tadalafil) and amiodorone. Whether a true causative relationship exists remains to be determined; however, patients with ischemic optic neuropathy should probably be instructed to avoid such medications if possible. Additionally, rare reports of optic neuropathy following LASIK and epi-LASIK have been described, possibly related to increased intraocular pressure from the suction ring.

Symptoms

Decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, visual field loss.

Signs

Unilateral or bilateral decreased visual acuity ranging from 20 / 20 to 20 / 400, decreased color vision, and decreased contrast sensitivity; RAPD if optic nerve damage is asymmetric (if symmetric damage, RAPD may be absent); optic disc pallor, retinal nerve fiber layer defects, visual field defects (central or cecocentral scotomas); abnormal visual evoked response; retrobulbar mass lesions may cause proptosis and motility deficits.

Differential Diagnosis

As above; normal-tension glaucoma.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Head and orbital CT scan or MRI to rule out intracranial processes or mass lesion.

• Consider lab tests: CBC; vitamin B1, B2, B6, B12, and folate levels; toxin screen; ELISA for Toxoplasma and Toxocara antibody titers, HIV antibody test, CD4 count, HIV viral load, urine CMV, purified protein derivative (PPD) and controls.

• Consider medical or oncology consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; poor once optic atrophy has occurred.

Congenital Anomalies

Definition

Variety of developmental optic nerve abnormalities.

Aplasia

Very rare, no optic nerve or retinal vessels present.

Dysplasias

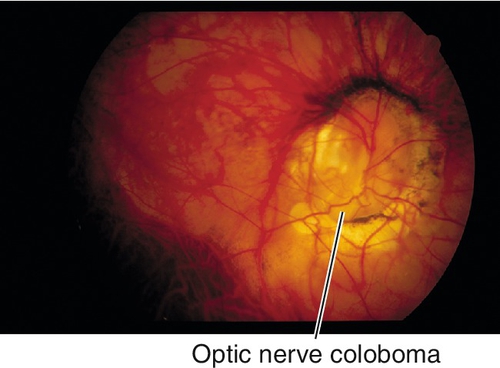

Coloboma

Spectrum of large, abnormal-appearing optic discs due to incomplete closure of the embryonic fissure; usually located inferonasally, often associated with other ocular coloboma. May be associated with systemic defects including congenital heart defects, double aortic arch, transposition of the great vessels, coarctation of the aorta, and intracranial carotid anomalies.

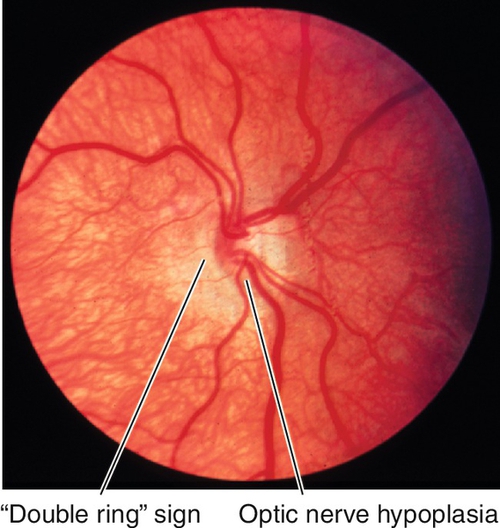

Hypoplasia

Small discs, “double ring” sign (peripapillary ring of pigmentary changes). Unilateral cases usually idiopathic; bilateral cases associated with midline abnormalities, endocrine dysfunction, and maternal history of diabetes mellitus or drug use (dilantin, quinine, alcohol, LSD) during pregnancy.

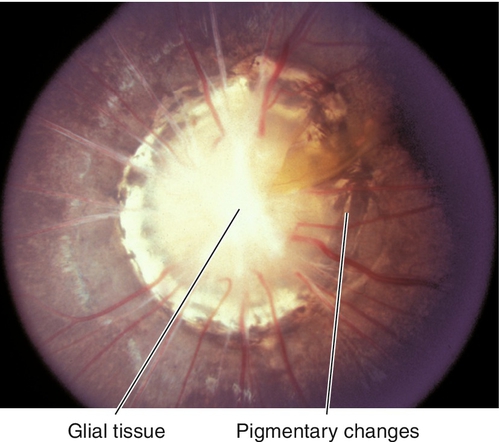

Morning Glory Syndrome

Large, unilateral, excavated disc with central, white, glial tissue surrounded by elevated pigment ring; may represent a form of optic nerve coloboma. Female predilection (2 : 1); usually severe visual loss; may develop a localized serous retinal detachment (source of fluid controversial: CSF vs vitreous). Associated with midline facial defects and forebrain anomalies. May be associated with the papillorenal syndrome, a PAX2 gene mutation.

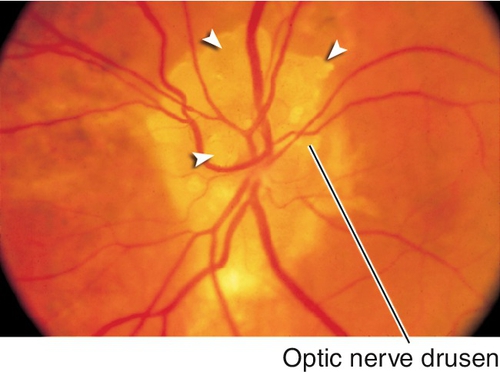

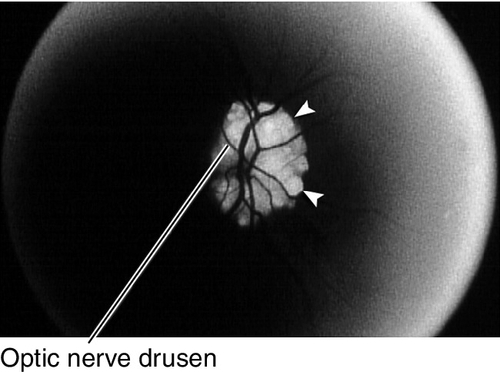

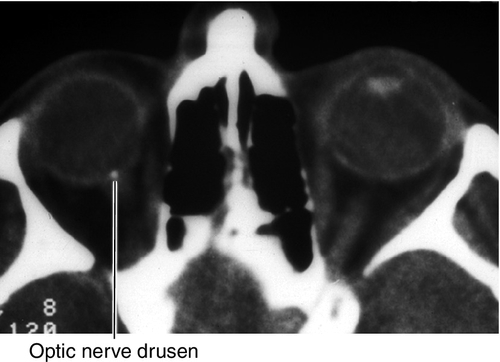

Optic Nerve Drusen

Superficial or buried hyaline-like material in the substance of the nerve anterior to the lamina cribrosa; may calcify. Seventy-five percent bilateral; may be hereditary (AD). Associated with retinitis pigmentosa; may develop visual field defects usually inferonasal or arcuate scotomas. No treatment needed.

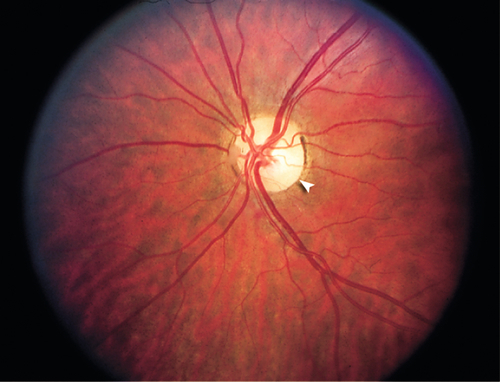

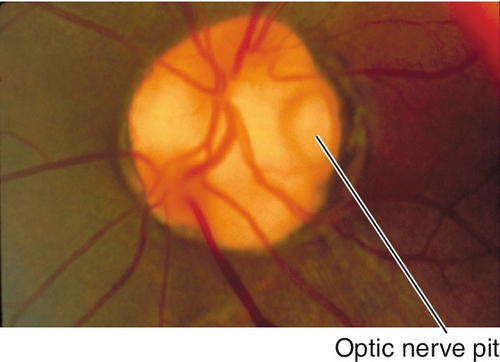

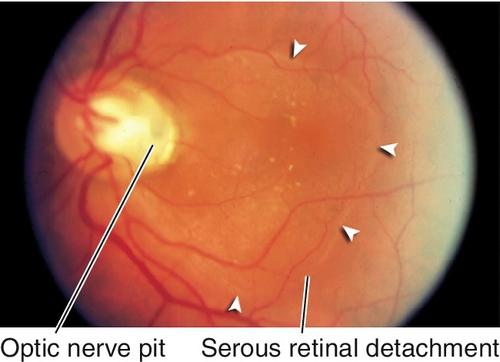

Pit

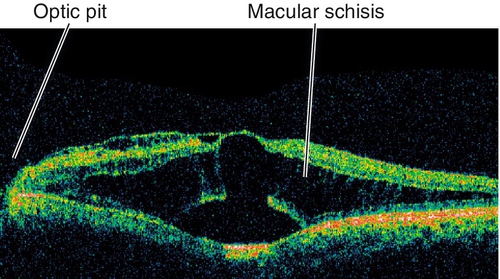

Depression in optic disc, 0.1–0.7 disc diameter, usually located temporally; appears gray-white; 85% unilateral. Peripapillary retinal pigment epithelium changes in 95%; 40% develop intraretinal fluid, mainly in outer retina, with schisis cavities. Can progress to subretinal fluid collection with a serous retinal detachment in teardrop configuration extending from the pit into the macula. Source of fluid (cerebrospinal fluid vs liquefied vitreous vs both) is controversial. Often a thin layer of tissue over the pit; serous retinal detachments can resolve spontaneously.

Septo-Optic Dysplasia (De Morsier Syndrome)

Syndrome of optic disc hypoplasia, absence of septum pellucidum, agenesis of corpus callosum, and endocrine problems; may have see-saw nystagmus. Associated with mutations in the HESX-1 gene.

Tilted Optic Disc

Displacement of one side of optic disc peripherally with oblique insertion of retinal vessels. Associated with high myopia (may have visual field defect that is usually felt to be refractive in nature with a staphyloma adjacent to the optic disc); can cause bitemporal visual field defects that do not respect the vertical midline.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision, metamorphopsia, or visual field loss.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, abnormal-appearing optic disc, variety of visual field defects; may have RAPD. Drusen can be visualized on B-scan ultrasonogram, CT scan, and MRI, and autofluorescence occurs on fluorescein angiogram.

Differential Diagnosis

See above; optic disc drusen may give appearance of papilledema (pseudopapilledema).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Fluorescein angiogram: Serous retinal detachment with early punctate fluorescence and late filling may be seen with optic pits; optic nerve drusen autofluoresce with only filter in place before any fluorescein administration.

• Optical coherence tomography: Schisis cavities in outer retina often with subretinal fluid accumulation. Excavation, often with herniation of dysplastic tissue, next to optic nerve visible in optic nerve cuts. Intraretinal and subretinal fluid tracks to excavation. Vitreous can sometimes be seen sucking into pit.

• Consider B-scan ultrasonography to identify buried drusen.

• Head and orbital CT scan for dysplasias.

• Endocrine consultation for hypoplasia.

Prognosis

Most congenitally anomalous discs are not associated with progressive visual loss. Decreased vision from compression, choroidal neovascularization, or central retinal artery or vein occlusion can occur rarely with optic nerve drusen. Basal encephalocele can occur in any of the dysplasias.

Tumors

Definition

Variety of intrinsic neoplasms (benign and malignant) that may affect the optic nerve anywhere along its course.

Angioma (von Hippel Lesion)

Retinal capillary hemangioma (see Chapter 10); benign lesion that may involve the optic nerve. May be associated with intracranial (especially cerebellar) hemangiomas (von Hippel–Lindau syndrome) (see Figs 10-213, 10-230, and 10-231).

Astrocytic Hamartoma

Benign, yellow-white lesion that occurs in tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis (see Chapter 10); may be smooth or have nodular, glistening, “mulberry-like” appearance. May be isolated, multiple, unilateral, or bilateral (see Figs 10-221 and 10-222).

Combined Hamartoma of Retina and Retinal Pigment Epithelium

A rare, peripapillary tumor composed of retinal, retinal pigment epithelial, vascular, and glial tissue. May cause epiretinal membranes with macular traction or edema (see Chapter 10; Fig. 10-239).

Glioma

There are two types:

Glioblastoma multiforme

Rare, malignant tumor found in adults who develop rapid, occasionally painful visual loss, with chiasmal extension the fellow eye may be involved. Aggressive tumor with blindness in months and death within 6–9 months if not completely excised; may have central retinal artery or central retinal vein occlusion as tumor compromises blood supply. Enlargement of optic canal present on CT scan; endocrine or neurologic deficits may appear if tumor invades other structures.

Juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma

Most common intrinsic neoplasm of the optic nerve, accounting for 65% of such tumors; benign. Two distinct growth patterns: intraneural glial proliferation (most common, growth occurs within individual fascicles) and perineural arachnoidal gliomatosis (PAG; characterized by florid invasion of the leptomeninges with relative sparing of the nerve itself). Ninety percent occur in the first and second decades with peak between 2 and 6 years of age. Causes gradual, unilateral, progressive, painless proptosis, decreased vision, RAPD, and optic disc edema; optic atrophy or strabismus may develop later; chiasmal involvement in 50% of cases. Orbital CT scan shows fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve; histologically characterized by Rosenthal fibers, pilocytic astrocytes, and myxomatous differentiation. Associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 in 25–50% of cases.

Melanocytoma

Benign, darkly pigmented tumor located over or adjacent to the optic disc, usually jet-black with fuzzy borders; rarely increases in size. More common in African-Americans. Malignant transformation is exceedingly rare.

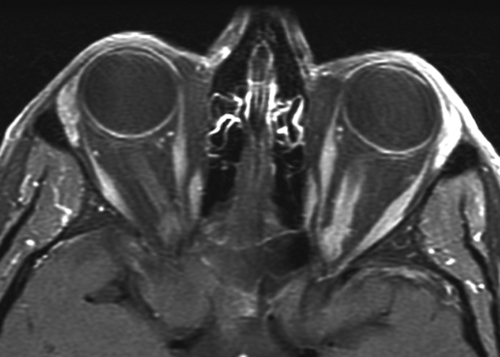

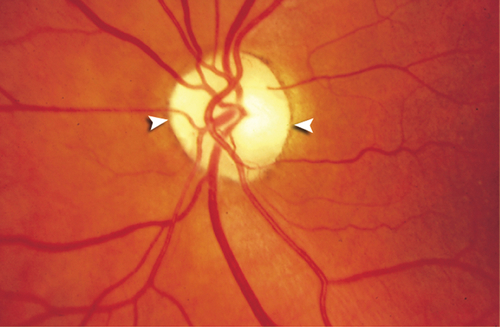

Meningioma

Rare, histologically benign tumor arising from optic nerve sheath arachnoid tissue or from adjacent meninges. Usually occurs in middle-aged females (3 : 1) in the third to fifth decades. Signs include unilateral proptosis, painless decreased visual acuity and color vision, RAPD, opticociliary shunt vessels, and optic nerve edema or atrophy. May grow rapidly during pregnancy and involute after delivery; optic nerve pallor and opticociliary shunt vessels occur later. Orbital CT scan demonstrates tubular enlargement of the optic nerve, hyperostosis, and calcification resulting in the “train-track” sign seen on axial views and “double-ring” appearance seen on coronal views. Histologic features include whorl pattern and psammoma bodies (meningocytes that form whorls around hyalinized calcium salts).

Figure 11-24 Fluorescein angiogram of same patient as Figure 11-23 demonstrating leakage of fluorescein from the optic disc.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, metamorphopsia with distortion of the posterior globe.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity and color vision, RAPD, proptosis, motility disturbances, increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve or peripapillary lesion, optic disc swelling or pallor, visual field defect; opticociliary shunt vessels in meningioma. Angiomas may rarely cause vitreous or retinal hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis

See above.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• B-scan ultrasonography to evaluate course of optic nerve.

• Fluorescein angiogram to rule out retinal angiomas.

• Head and orbital CT scan or MRI (also to rule out intracranial lesions): Optic nerve enlargement, train track sign (ring-like calcification of outer nerve), or bony erosion of optic canal.

Prognosis

Good for benign lesions, variable for meningiomas, and poor for malignant lesions.

Chiasmal Syndromes

Definition

Variety of optic chiasm disorders that cause visual field defects.

Epidemiology

Mass lesions in 95% of cases, usually pituitary tumor. Most lesions are large, because chiasm is 10 mm above the sella turcica (microadenomas do not cause field defects); may occur acutely with pituitary apoplexy secondary to hemorrhage or necrosis.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have headache, decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, visual field loss, diplopia, or vague visual complaints. Systemically decreased libido, malaise, galactorrhea or inability to conceive may be present.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity and color vision; may have RAPD, optic atrophy, visual field defect (junctional scotoma, bitemporal hemianopia, incongruous homonymous hemianopia), or signs of pituitary apoplexy (severe headache, ophthalmoplegia, and decreased visual acuity).

Differential Diagnosis

Pituitary tumor, pituitary apoplexy, meningioma, aneurysm, trauma, sarcoidosis, craniopharyngioma, chiasmal neuritis, glioma, ethambutol.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields with attention to vertical midline.

• Head and orbital CT scan or MRI (emergent if pituitary apoplexy suspected).

• Lab tests: Consider checking hormone levels.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; pituitary tumors have a fairly good prognosis.

Congenital Glaucoma

Definition

Congenital: onset of glaucoma from birth to 3 months of age (infantile, 3 months to 3 years; juvenile, 3 to 35 years).

Epidemiology

Incidence of 1 in 10,000 births. Three forms: approximately one-third primary, one-third secondary, one-third associated with systemic syndromes or anomalies.

Primary

Seventy percent bilateral, 65% male, multifactorial inheritance, 40% at birth, 85% by 1 year of age. Mapped to chromosomes 1p36 (GLC3B gene) and 2p22-p21 (GLC3A gene, CYP1B1 gene). A mutation in the CYP1B1 gene accounts for ~ 85% of congenital glaucoma.

Secondary

Inflammation, steroid-induced, lens-induced, trauma, tumors.

Associated Syndromes

Mesodermal dysgenesis syndromes, aniridia, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, nanophthalmos, rubella, nevus of Ota, Sturge–Weber syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Marfan’s syndrome, Weill–Marchesani syndrome, Lowe’s syndrome, mucopolysaccharidoses.

Mechanism

Primary

Developmental abnormality of the angle (goniodysgenesis) with faulty cleavage and abnormal insertion of ciliary muscle. Associated with mutations in the CYP1B1 gene, a member of the cytochrome p450 gene family.

Symptoms

Epiphora, photophobia, blepharospasm.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity, myopia (primary or secondary to pressure-induced change), amblyopia, increased intraocular pressure, corneal diameter > 12 mm by 1 year of age, corneal edema, Haab’s striae (breaks in Descemet’s membrane horizontal or concentric to limbus; see Figure 5-68), optic nerve cupping (may reverse with treatment), buphthalmos (enlarged eye).

Differential Diagnosis

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction, megalocornea, high myopia, proptosis, birth trauma, congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy of the cornea, sclerocornea, metabolic diseases.

Evaluation

• May require examination under anesthesia. Note: Intraocular pressure affected by anesthetic agents (transiently increased by ketamine; decreased by inhalants).

• Check visual fields in older children.

Prognosis

Usually poor; best for primary congenital form and onset between 1 and 24 months of age.

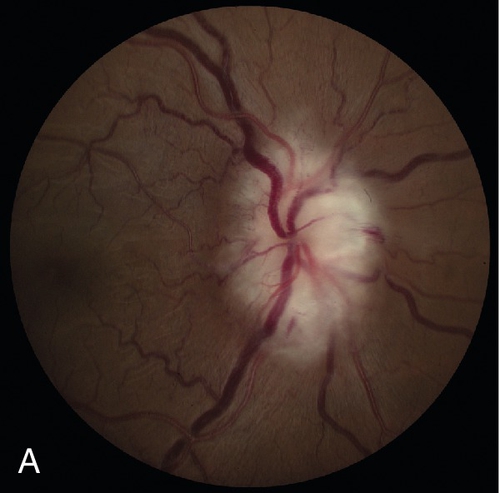

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG)

Definition

Progressive, bilateral, optic neuropathy with open angles, typical pattern of nerve fiber bundle visual field loss, and increased intraocular pressure (IOP > 21 mmHg) not caused by another systemic or local disease (see Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma section).

Epidemiology

Occurs in 2–5% of population > 40 years old; risk increases with age; most common form of glaucoma (60–70%); no sex predilection. Risk factors are increased intraocular pressure, increased cup : disc ratio, thinner central corneal thickness (less than ~ 550 μm by ultrasound or ~ 520 μm by optical pachymetry), race (African-Americans are 3–6 times more likely to develop POAG than Caucasians; POAG also occurs earlier, is six times more likely to cause blindness, and is the leading cause of blindness in African-Americans), increased age, and positive family history in first-degree relatives (parents, siblings). Inconsistently associated factors include myopia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Mapped to chromosomes 2qcen-q13 (GLC1B gene), 2p15-p16 (GLC1H gene), 3q21-q24 (GLC1C gene), 5q22 (GLC1G gene), 7q35-q36 (GLC1F gene), 8q23 (GLC1D gene), 10p14 (GLC1E gene, OPTN gene). A mutation in the OPTN gene accounts for ~ 17% of POAG.

Mechanism

Elevated Intraocular Pressure

Mechanical resistance to outflow (at juxtacanalicular meshwork), disturbance of trabecular meshwork collagen, trabecular meshwork endothelial cell dysfunction, basement membrane thickening, glycosaminoglycan deposition, narrowed intertrabecular spaces, collapse of Schlemm’s canal. A subgroup of patients has been identified with mutations of the myocilin glycoprotein. This protein is also mutated in patients with autosomal dominant juvenile open-angle glaucoma (GLC1A, MYOC / TIGR gene), which has been mapped to chromosome 1q23-q25.

Optic Nerve Damage

Various theories:

Mechanical

Compression of optic nerve fibers against lamina cribrosa with interruption of axoplasmic flow.

Vascular

Poor optic nerve perfusion or disturbed blood flow autoregulation.

Other pathways leading to ganglion cell necrosis or apoptosis

Excitotoxicity (glutamate), neurotrophin starvation, autoimmunity, abnormal glial–neuronal interactions (TNF), defects in endogenous protective mechanisms (heat-shock proteins).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or constricted visual fields in late stages.

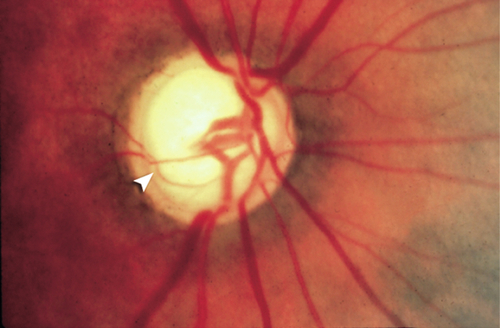

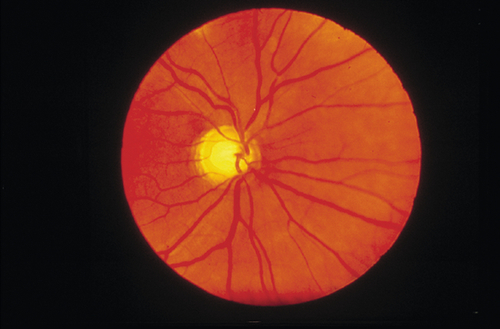

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, splinter hemorrhages at optic disc, retinal nerve fiber layer defects, visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

Secondary open-angle glaucoma, normal-tension glaucoma, ocular hypertension, optic neuropathy, physiologic cupping.

Evaluation

• Check corneal pachymetry (IOP measurement by applanation tonometry may be artifactually high or low for thicker or thinner than average corneas, respectively).

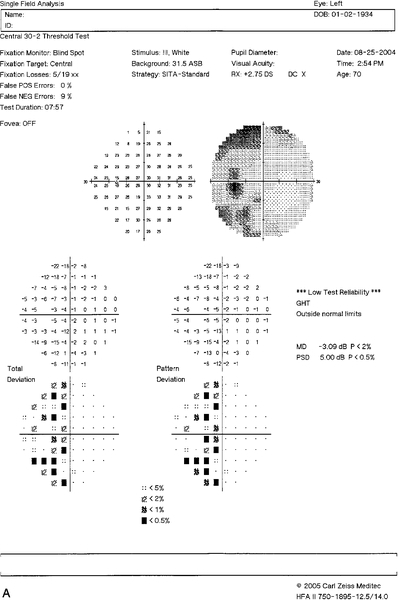

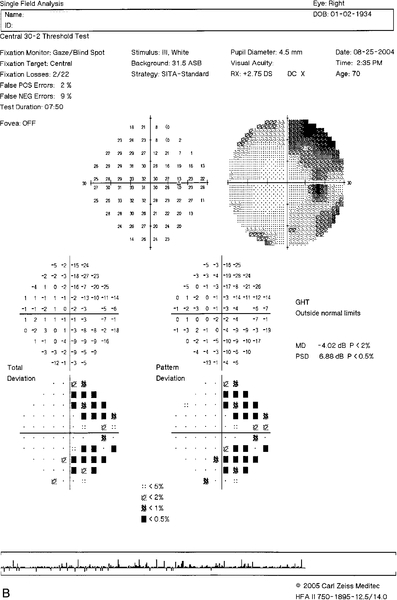

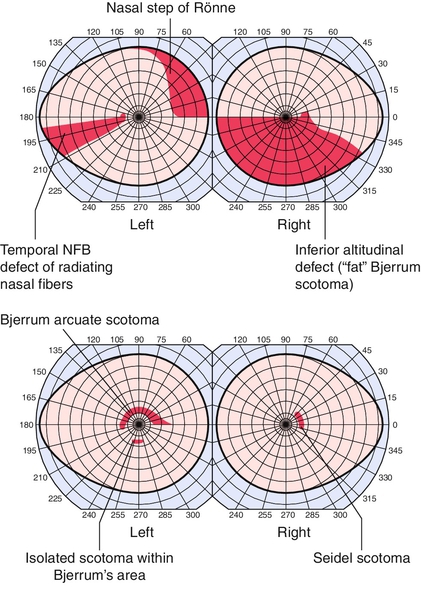

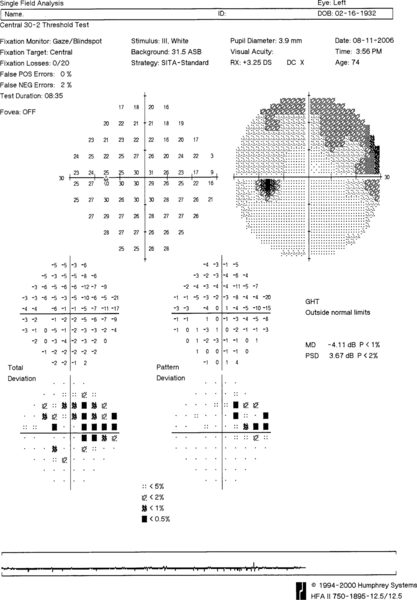

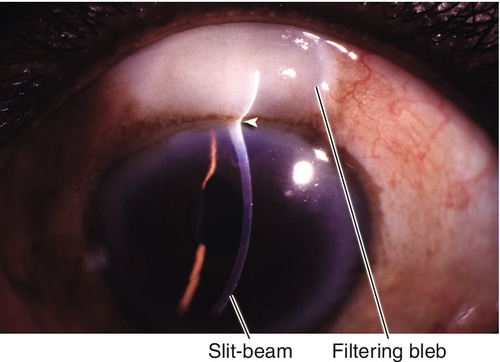

• Visual fields: Visual field defects characteristic of glaucoma include paracentral scotomas (within central 10° of fixation), arcuate (Bjerrum) scotomas (isolated, nasal step of Ronne, or Seidel [connected to blind spot]), and temporal wedge.

• Stereo optic nerve photos to document optic nerve appearance; useful for comparison at subsequent evaluations.

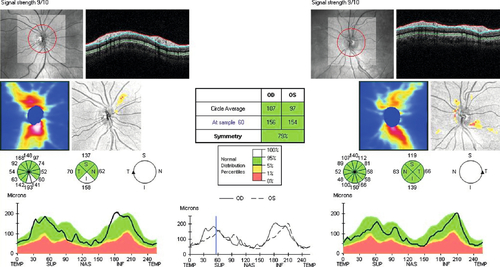

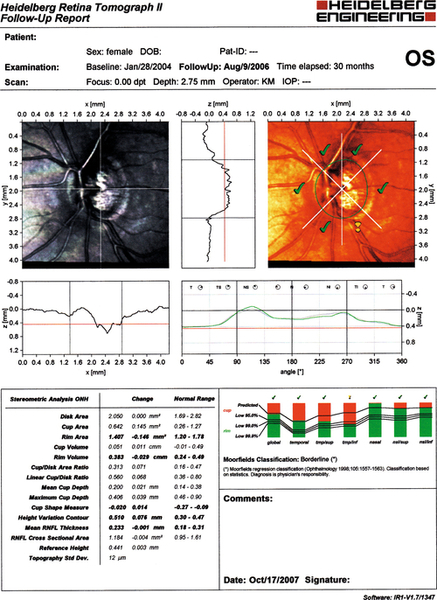

• Optic nerve head analysis: Various methods including confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (HRT, TopSS), optical coherence tomography (OCT), scanning laser polarimetry (Nerve Fiber Analyzer, GDx), and optic nerve blood flow measurement (color Doppler imaging and laser Doppler flowmetry).

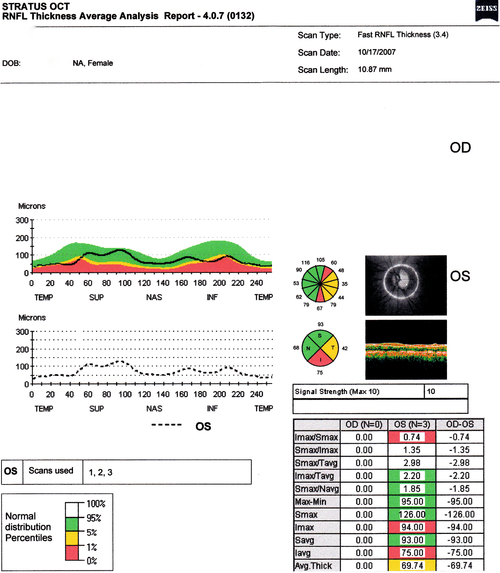

Figure 11-32 Heidelberg retinal tomograph (HRT) of same patient as Figure 11-31 demonstrating inferotemporal nerve fiber layer thinning (yellow exclamation point).

Figure 11-33 Stratus OCT evaluation of same patient as Figure 11-31 demonstrating inferotemporal nerve fiber layer thinning (red and yellow quadrants).

Prognosis

Variable; depends on extent of optic nerve damage since visual loss is permanent. Usually good if detected early and intraocular pressure is controlled adequately; worse in African-Americans.

Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma

Definition

Open-angle glaucoma caused by a variety of local or systemic disorders.

Etiology

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome (see Chapter 8), pigment dispersion syndrome (see Chapter 7), uveitis, lens-induced (see Chapter 8), intraocular tumors, trauma, and drugs; also elevated episcleral venous pressure (orbital mass, thyroid-related ophthalmopathy, arteriovenous fistulas, orbital varices, superior vena cava syndrome, Sturge–Weber syndrome, idiopathic), retinal disease (retinal detachment, retinitis pigmentosa, Stickler’s syndrome), systemic disease (pituitary tumors, Cushing’s syndrome, thyroid disease, renal disease), postoperative (laser and surgical procedures), and uveitis–glaucoma–hyphema syndrome (see Chapter 6).

Drug Induced

Steroids

Most common; possibly due to increased trabecular meshwork (TM) glycosaminoglycans. Steroid-related intraocular pressure elevation correlates with potency and duration of use; 30% of population develop increased intraocular pressure after 4–6 weeks of topical steroid use, intraocular pressure > 30 mmHg in 4%; 95% of patients with POAG are steroid responders; increased incidence of steroid response in patients with diabetes mellitus, high myopia, connective tissue disease, and family history of glaucoma.

Viscoelastic agents

Used during ophthalmic surgery, can transiently obstruct the TM (1–2 days).

α-Chymotrypsin

Used for intracapsular cataract extraction, produces zonular debris, which can block the TM.

Intraocular Tumor

Due to hemorrhage, angle neovascularization, direct tumor infiltration of the angle, or TM obstruction by tumor, inflammatory, or red blood cells.

Traumatic

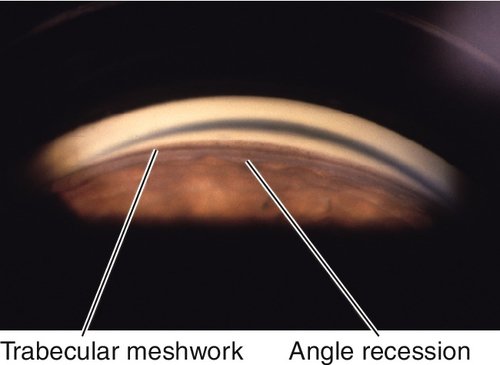

Angle recession

If more than two-thirds of the angle is involved, 10% of patients develop glaucoma from scarring of angle structures.

Chemical injury

Toxicity to angle structures from direct or indirect (prostaglandin, ischemia-mediated) damage.

Hemorrhage

Red blood cells, ghost cells (degenerated red blood cells), or macrophages that have ingested red blood cells (hemolytic glaucoma) obstruct the TM; increased incidence in patients with sickle cell disease.

Siderosis or chalcosis

Toxicity to angle structures from iron or copper intraocular foreign body.

Uveitic

Due to outflow obstruction from inflammatory cells, trabeculitis, scarring of the TM, or increased aqueous viscosity.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have pain, photophobia, decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, optic nerve cupping, nerve fiber layer defects, visual field defects; may have blood in Schlemm’s canal evident on gonioscopy (due to elevated episcleral venous pressure) or other signs of underlying etiology:

Intraocular Tumor

Iris mass, focal iris elevation, hyphema, hypopyon, anterior chamber cells and flare, pseudohypopyon, leukocoria, segmental cataract, invasion of angle, extrascleral extension, sentinel episcleral vessels.

Traumatic

Anterior chamber cells and flare, other signs of trauma including red blood cells in anterior chamber or vitreous, angle recession, iridodialysis, cyclodialysis, sphincter tears, iridodonesis, phacodonesis, cataract, corneal blood staining, corneal scarring, scleral blanching or ischemia, intraocular foreign body, iris heterochromia, retinal tears, choroidal rupture.

Uveitic

Ciliary injection, anterior chamber cells and flare, keratic precipitates, miotic pupil, peripheral anterior synechiae, posterior synechiae, iris heterochromia, iris atrophy, iris nodules, fine-angle vessels, decreased corneal sensation, corneal edema, corneal scarring, ghost vessels, cataract, low intraocular pressure due to decreased aqueous production, cystoid macular edema.

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider ultrasound biomicroscopy to evaluate angle and ciliary body.

• Consider orbital radiographs or head and orbital CT scan to rule out intraocular foreign body.

• Consider uveitis workup.

• May require medical or oncology consultation.

Prognosis

Poorer than primary open-angle glaucoma because usually due to chronic process; depends on etiology, extent of optic nerve damage, and subsequent intraocular pressure control; typically good for drug induced if identified and treated early.

Normal (Low)-Tension Glaucoma

Definition

Similar optic nerve and visual field damage as in POAG, but with normal intraocular pressure (≤ 21 mmHg).

Epidemiology

Higher prevalence of vasospastic disorders including migraine, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ischemic vascular disease, autoimmune disease, and coagulopathies; also associated with sleep apnea and history of poor perfusion of the optic nerve from hypotension (nocturnal systemic hypotension) or hemodynamic crisis (shock, myocardial infarction, or massive hemorrhage).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision or constricted visual fields in late stages.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, normal intraocular pressure (≤ 21 mmHg), optic nerve cupping, splinter hemorrhages at optic disc (more common than in POAG), peripapillary atrophy, nerve fiber layer defects, visual field defects.

Differential Diagnosis

POAG (undetected increased intraocular pressure or artifactually low intraocular pressure secondary to thin cornea [e.g., naturally occurring or after LASIK or PRK]), secondary glaucoma (steroid-induced, “burned out” pigmentary or postinflammatory glaucoma), intermittent angle-closure glaucoma, optic neuropathy, optic nerve anomalies, glaucomatocyclitic crisis (Posner–Schlossman syndrome).

Evaluation

• Check visual fields.

• Check corneal pachymetry.

• Consider diurnal curve (intraocular pressure measurement q2h for 10–24 hours) and tonography.

• Consider evaluation for other causes of optic neuropathy: check color vision, lab tests (CBC, ESR, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-ABS] test, antinuclear antibody [ANA]), neuroimaging, or cardiovascular evaluation if age less than 60 years old, decreased visual acuity without apparent cause, visual field defect not typical of glaucoma, visual field and disc changes do not correlate, rapidly progressive, unilateral or markedly asymmetric, or nerve pallor greater than cupping.

Prognosis

Poorer than primary open-angle glaucoma.