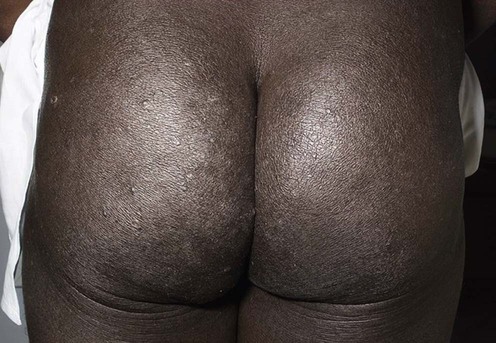

Onchocerciasis

First-line therapies

Other therapies

WHO researchers start trial on a new drug for river blindness.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is supporting research to optimize treatment regimens (Death of Onchocerciasis and Lymphatic Filariasis, DOLF; www.dolf.wustl.edu). Studies include attempts to reformulate flubendazole, a known effective macrofilaricide, in order to improve its bioavailability.

Ivermectin

Ivermectin Ivermectin combined with doxycycline

Ivermectin combined with doxycycline Albendazole

Albendazole Suramin

Suramin Future therapies: new macrofilaricides

Future therapies: new macrofilaricides