Update on Precocious Puberty: Girls are Showing Signs of Puberty Earlier, but Most Do Not Require Treatment

Precocious puberty is one of the most common endocrine disorders seen by primary care physicians and continues to be a major source of concern for both parents and providers. Since the author’s previous review on this subject in Advances In Pediatrics in 2004 [1], there have been several reports that have added to the knowledge base and confirmed that signs of puberty in girls are appearing earlier than in the past in the United States as well as in other countries. In this article, the author reviews what pediatricians should know about the physical findings seen during normal puberty and their hormonal basis. The evidence that signs of puberty are appearing earlier than 30 to 40 years ago, at least in girls, and the major theories about why this might be occurring are also discussed. However, the key point to be made is that pediatricians should be able to recognize the benign causes of early breast and pubic hair development, which are, at least in the United States, far more common than the cases that might benefit from treatment. The current state of knowledge concerning the diagnosis and treatment of central (true) precocious puberty (CPP) and the red flags that might point toward one of the rare causes of gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty (GIPP) are then reviewed.

Review of normal puberty

In girls, the first sign of true puberty is breast development, caused by estrogens produced by the ovaries, under the influence of increased pituitary secretion of the gonadotropin, luteinizing hormone (LH). There is also an increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which is more critical for maturation of the immature oocytes. Traditionally, it has been thought that the normal age range for this event, also called thelarche, is between 8 and 13 years; however, as discussed later, there is ample evidence that in many healthy girls, this event can occur before the age of 8 years. Shortly after breasts appear, the pubertal growth spurt starts, and menarche occurs 2 to 3 years later because gonadotropin secretion increases so that there is a midcycle surge of LH, which triggers ovulation.

According to a recent longitudinal study, the appearance of pubic and/or axillary hair follows the appearance of breast tissue in 66% of girls [2]. This occurrence is often confused with the onset of puberty, but has a different hormonal basis, due to an increase in the production of weak adrenal androgens, primarily dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), an event known as adrenarche. In the average girl, adrenarche starts between the ages of 9 and 11 years but is not uncommon in girls aged 6 to 8 years, a situation called premature pubarche or premature adrenarche (PA), which is discussed below.

In boys, the earliest reliable sign of puberty is enlargement of the testes (>3 cm3 in volume or >2.5 cm in diameter) under the influence of increased FSH secretion, which occurs at an average age of 11 to 12 years but can occur as early as age 9 years. It typically takes 12 to 18 months after testicular enlargement for testosterone production, under the influence of increasing LH secretion, to increase and cause penile growth and the growth spurt, which in the average boy peaks at 13 to 14 years of age. A recent longitudinal study found that testicular enlargement preceded pubic hair development in 91% of boys [2], but pubic hair may occur several years earlier than genital development because of increased adrenal androgen secretion.

Are girls maturing earlier? If so, how should we define when pubertal development is precocious?

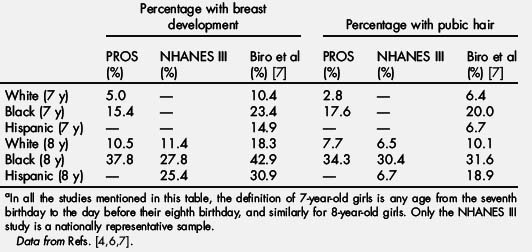

For many years, going back to the classic study of Marshall and Tanner [3] in the 1960s, which was based on a nonrandom sample of 192 white British girls living in a group home, the age at which puberty was considered precocious in girls was by consensus thought to be 8 years. A landmark study in 1997, based on 17,000 girls aged 3 to 12 years examined in 65 pediatric offices participating in the Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) network, confirmed what many had already suspected: that appearance of breasts and pubic hair in girls before age 8 years was common [4]. In 8-year-old girls (defined as from the eighth birthday to the day before the ninth birthday), 37.8% of black and 10.5% of white girls had at least Tanner stage 2 breast development, and a similar percentage had pubic hair. Even for 7-year-old girls, the numbers were high, 15.4% of black and 5% of white girls had breast development. An article written by the author suggested revising the definition of precocious puberty in girls downward to age 7 years in white girls and age 6 years in black girls to take into account this new data [5]. However, many objected to this recommendation on the basis that the PROS study was flawed because of the participants not being a randomized sample. In addition, because the Tanner staging was done mainly by inspection and not palpation, the results may have been biased because of the problems distinguishing breast tissue from fat tissue in chubby girls. However, similar results were found in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-III), which from 1988 to 1994 examined pubertal status in 1623 girls between the ages of 8 and 16 years who were scientifically selected to represent the general population [6]. Recently, new data were reported by Biro and coworkers [7] who examined a cohort of 1239 girls aged 7 and 8 years recruited from 3 centers in East Harlem (NY), greater Cincinnati (OH), and the San Francisco Bay area (CA). The investigators found that the proportion of girls in this group with breast development confirmed by palpation may be even higher than in the 2 earlier studies. The results of these 3 studies are summarized in Table 1. Although there are differences in the numbers reported, the key point is that all studies show a high incidence of early breast development and pubic hair in girls aged 7 to 8 years from all regions of the United States, with the highest percentages seen in black girls.

Table 1 Proportion of 7- and 8-year-old girlsa with breast development and pubic hair from 3 recent US studies

Another way of looking at pubertal trends in girls is to calculate the mean age of 2 pubertal milestones: thelarche and menarche. The PROS and NHANES-III studies found that the mean age of thelarche, 10.0 to 10.3 years in white girls and 8.8 to 9.5 years in black girls, was earlier than that in previous studies done in the United States and the United Kingdom, which had indicated that the mean age was closer to 11 years. Until recently, most studies from Europe and other industrialized countries had not found any decrease in the mean age of breast development from the 1960s to the 1990s. However, the Copenhagen Puberty Study done from 2006 to 2008 found that girls attained stage 2 breast development at a mean age of 9.86 years, a full year earlier than the previous study done in 1991 to 1993 by the same research group, using the same methodology [8]. Even when adjustments were made for body mass index (BMI), which changed little between the 2 cohorts, the difference remained significant. Furthermore, a recent study on more than 20,000 healthy girls living in China found that the median age for Tanner stage 2 breast development was only 9.2 years, with the median age for Tanner 2 pubic hair significantly later at 11.16 years and the median age at menarche 12.27 years [9]. Despite the rather dramatic declines reported for the mean age of thelarche, changes in the mean age at menarche have been more modest. In the United States, the PROS study found no decrease in age at menarche when compared with an earlier study in 1966 to 1970 (both 12.7–12.8 years), whereas in the NHANES III study, age at menarche decreased slightly to 12.5 years [6]. A more recent NHANES survey done from 1999 to 2004 found the mean age at menarche for women born from 1980 to 1984 to be 12.4 years [10]. In the Copenhagen study, the mean age at menarche declined from 13.42 years in 1991 to 13.13 years in 2006, again less than the magnitude of the decline in the mean age at thelarche [8]. It is also noteworthy that the mean interval from thelarche to menarche was (13.13−9.82) 3.3 years, much longer than the mean interval of 2.3 ± 1.1 years reported by Marshall and Tanner [3]. This finding suggests either 1) that it now takes long for most girls to progress from thelarche to menarche than in the past or 2) that a significant number of contemporary girls have a nonprogressive or slowly progressive variant of puberty and may not progress at all for a year or two after the first sign of breast development [11].

The key question pediatricians struggle with remains this: given that many studies show a trend toward earlier breast (as well as pubic hair) development, at what age should signs of puberty in girls be considered abnormal and thus trigger a referral to an endocrinologist. As noted earlier, a 1999 review suggested that the age limits for when puberty is considered precocious should be decreased to 7 years in white and 6 years in black girls [5]. Although the proportion of 7-year-old girls with signs of puberty is quite high, most specialists and pediatricians still feel more comfortable with the traditional cutoff of 8 years, even though this cutoff labels many girls as abnormal who are undoubtedly at the lower end of the current normal range for pubertal maturation. The author believes that rather than focusing on one age as separating normal from abnormal, the rate of progression of pubertal maturation in deciding how concerned to be about a particular child should be taken into account. For example, in a 7.5-year-old girl with a small amount of breast tissue (Tanner stage 2) on examination and no evidence of a growth spurt, pubertal maturation may progress slowly and often the findings remain the same 6 months later; this girl does not benefit from treatment to suppress puberty (see later). On the other hand, an 8.25-year-old girl who is at Tanner 3 for breast development and has grown 3–4 inches in the past year is clearly progressing more rapidly and needs prompt evaluation. In addition, pediatricians should be more concerned about girls with early and progressive breast development with or without pubic hair than girls who only have pubic hair because girls in the latter group rarely have a condition requiring intervention.

Are boys maturing earlier than in the past and when should they be referred?

For many years, the definition of precocious puberty in boys has been signs of maturation starting before the age of 9 years, but there have been relatively few studies on whether the mean age at the onset of puberty in boys has decreased over the past 30 to 40 years. One report based on the NHANES III study seemed to indicate that stage 2 genital growth, a more reliable sign of puberty in boys than pubic hair, was occurring much earlier than earlier studies had found, with a mean age of about 10 years [12]. However, the accuracy of sexual maturation ratings in this survey has been questioned. A study of male puberty in the United States undertaken by the PROS network is nearing completion, and these data should be available in the near future. In the Copenhagen Puberty Study, it was recently reported that compared with the period from 1991 to 1993, boys examined during 2006 to 2008 had slightly earlier attainment of testicular volume of greater than 3 cm3, which correlated with an increase in BMI [13]. Unlike the situation for girls, it is generally agreed that endocrinologists have observed no increase in the past 40 years in the number of boys referred for true precocious puberty. At present there is no reason to change the age at which pubertal development in boys is considered precocious, which should remain 9 years.

What can we say about why girls are starting puberty earlier?

This topic was discussed at length in the author’s article in 2004 for this series, and in this section, the author mainly highlights recent articles that bear on the subject. The relationship between increased body fat (typically measured as elevated BMI for age) and earlier puberty has been summarized in a recent review [14]. Multiple studies have documented that higher BMI (which is a good surrogate measure of increased body fat) is correlated with earlier onset of breast development, pubic hair, and menarche. Although the precise cause of this relationship is not known, one possibility is that higher levels of the fat cell–derived protein leptin, seen in children with increased body fat, allow puberty to start earlier. Leptin is required for normal gonadotropin secretion because mice and humans lacking the ability to produce or respond to leptin fail to make LH and FSH, and providing leptin to leptin-deficient mice results in the onset of puberty. One area of debate is whether earlier puberty itself is the cause of the increase in body fat or if an increase in body fat precedes and causes the earlier appearance of breast development. A recent article by Lee and colleagues [15] presented findings that favor the latter interpretation. The study included 354 girls from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development for whom there was longitudinal data on BMI at ages 36 and 54 months and grades 1, 4, 5, and 6, with pubertal assessments by physical examination in grades 4 to 6. The investigators found that elevated BMI standard deviation scores at ages 36 and 54 months and in grade 1 and the rate of change in BMI from 36 months to grade 1 were associated with increased odds of earlier puberty (defined as Tanner ≥2 breasts in grade 4 or Tanner ≥3 breasts in grade 6). This finding suggests that well before the onset of puberty, as early as 3 years of age, the presence of increased BMI is an important factor in determining the age of onset of puberty in girls in the United States. It is curious that the same relationship between increased BMI and the timing of puberty has not consistently been found in boys. A recent study from the same group found that boys who were in the highest BMI trajectory through 11.5 years had a significantly higher chance of remaining prepubertal than boys in the lowest BMI trajectory [16], suggesting that increased body fat does not promote earlier puberty in boys, at least in the United States; this contrasts with the recent findings in Danish boys.

Many clinicians and investigators have proposed that chemicals in the environment with weak estrogenlike properties, including certain pesticides, phthalates, bisphenol A, and plant-derived phytoestrogens, or low levels of estrogens itself in the food supply are driving the trend toward earlier puberty in girls [17,18]. The investigators of one review pointed out that prepubertal girls are extremely sensitive to low levels of exogenous estrogens and that exposures previously thought to be safe based on less-sensitive measures of estradiol levels in young children may in fact have important effects on growth and pubertal development, even at levels below the detection limits of most assays [17]. However, except in a few isolated cases, evidence for specific exposures linked to earlier onset of puberty has been difficult to come by. Research on such exposures in girls with earlier pubertal development is ongoing, but it is recognized that examining blood or urine levels of these chemicals in a 7- to 8-year-old girl may miss a potentially higher level of exposure to one or more of these chemicals in the critical perinatal period.

Common variations of pubertal development

Pediatricians confronted with a child with early breast development or pubic hair need to know how to distinguish the common benign normal variations from children who need prompt referral for possibly treatable conditions, as well as the limited usefulness of hormone testing and radiography in evaluating such children.

Premature adrenarche

PA is the most common cause of referrals for precocious puberty in many US centers. Table 1 suggests why this entity is so common, especially in black girls, and why it may represent, at least in 6- to 8-year old girls, the lower end of the normal range for pubic hair development. At the author’s institution, which serves the DC region, over a 2-year period, 430 boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 9 years were referred for signs of early puberty, and 62% were diagnosed as having PA. Of these, 82% were girls. In other parts of the world, the proportion of puberty referrals with PA seems to be much lower. For example, in Israel, of a group of 453 children seen for early puberty over a 5-year period, only 22.2% were diagnosed with PA, whereas 34.4% had CPP [19]. This finding may be at least in part because in certain regions in the United States, there is a high proportion of black children who, as noted in Table 1, are 2 to 3 times more likely than white girls to have early appearance of pubic hair.

The typical features of PA are pubic and/or axillary hair, often accompanied by an adult-type axillary odor, without breast development in girls or penile or testicular enlargement in boys. The amount of pubic hair increases slowly over time, and in many cases, there may be growth acceleration in the year or two before referral, so that most such children are taller than average. The hormonal basis of PA is a precocious increase in secretion of weak androgens of adrenal origin (referred to as adrenarche), primarily DHEA, which is converted to an easily measured storage form, DHEA sulfate (DHEA-S). The cause of this increase is not clear, but it does not seem to be because of an increase in pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels because cortisol levels, which increase when the ACTH level is elevated, are not increased. Several studies have identified obesity as a risk factor for earlier appearance of pubic hair [20,21], but not all children with PA are obese. Another risk factor is having low birth weight. A recent study from Barcelona, Spain found that girls with PA are twice as likely to reach menarche before age 12 years compared with control girls, and among the subset of girls with PA who had low birth weight, menarche before age 12 years was 3-fold more prevalent and adult height was less compared with those in girls who did not have low birth weight [22].

Many pediatricians worry that the appearance of early pubic hair is associated with pathologic conditions often enough that hormonal testing is recommended before referral, as well as radiography of the hand for bone age. In PA, the only hormone level elevated for age is DHEA-S, typically in the range of 30 to 150 μg/dL (DHEA levels are elevated as well but vary much more by time of day than DHEA-S levels and are not clinically useful). The differential diagnosis of early pubic hair development includes adrenal and gonadal androgen-secreting tumors in which DHEA-S levels, testosterone levels, or both are extremely elevated, but those rare cases are generally not difficult to detect because there is enlargement of the clitoris or penis and marked growth acceleration. More difficult to detect clinically but far less worrisome are cases of late-onset or nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to partial 21-hydroxylase deficiency, the only manifestation of which may be early pubic hair. Studies in which ACTH stimulation testing (the gold standard for diagnosis) has been done in a series of children with PA to check for an exaggerated increase in 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) levels have found that between 2% and 8% of children have hormonal findings compatible with nonclassical CAH. A recent study from Paris found nonclassical CAH in 4% of 238 children presenting with early pubic hair, and all had basal 17-OHP levels greater than 200 ng/dL (normal levels in prepubertal children are generally <100 ng/dL) [23].

Testosterone levels may be mildly elevated (20–30 ng/dL) in girls and boys with PA when the tests are run in laboratories which use a traditional radioimmunoassay that is not specific enough for young children. When tested by a more accurate method, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry, levels are virtually always less than 15 ng/dL. Determination of LH, FSH, and estradiol levels are often recommended in girls with PA but are not helpful because when there is no breast development, there is no need to look for evidence of activation of the pituitary-gonadal axis. In general, it is best to leave the decision as to which tests to order the endocrinologist who will be seeing the child.

The value of a bone age as a screening test to identify pathologic causes of early pubic hair is questionable. The author has seen many cases in which, as a result of finding a bone age advanced by 2 or more years, a large number of tests were recommended, including multiple hormone levels; adrenal and/or pelvic ultrasonography; and, in some cases, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which did not add anything to the diagnosis. Of the 121 children with PA seen in our department who had a bone age x-ray, 30% had a bone age advanced by 2 or more years [24]. The main difference between these children and those with normal bone ages was that they had greater height and BMI standard deviation scores (ie, they were taller and more likely to be obese). Because bone age advancement is common in PA, is a poor predictor of pathology, and generates considerable anxiety on the part of referring physicians and parents, it is suggested that the decision to order a bone age X-ray be left to the endocrinologist who examines the child.

Several studies have found that girls with PA have an increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome in the teenage years, particularly for those girls who are born small for gestational age and who are obese [25]. Thus, counseling families of girls with PA on the need to maintain normal body weight is important, and referring those who experience very irregular periods in adolescence to pediatric endocrinologists is advised.

Premature thelarche

Another scenario often encountered is the girl who develops breast tissue, which during a period of observation does not progress. A recent review of 139 cases of premature thelarche (PT) seen at a single center in Israel over a 10-year period indicated that in 42% breast tissue appeared at birth, in 43% between 1 and 24 months, and in only 15% between ages 2 and 8 years [26]. Breast development was bilateral in 78% but had reached stage 3 in only 11%. In most such cases, there is no growth acceleration; pubic hair is occasionally also present but is typically absent. The Israeli study reported that during follow-up, PT regressed in 51%, persisted in 36%, and progressed in only 3%, and 10% had a cyclic course [26]. Therefore, parents should not be counseled to expect resolution of breast tissue. Some investigators have suggested that progression to true precocious puberty occurs often enough that children with this condition need to be monitored for prolonged periods, but the author has never seen this occur in a child with PT starting at less than 3 years of age. Because true precocious puberty starting before age 3 years is uncommon [27], the best approach is reassurance and periodic monitoring of the size of the breasts and the rate of growth, which can be done by the primary care pediatrician after an initial consultation. Laboratory testing is not very helpful in classic cases because LH, FSH, and estradiol levels are invariably in the prepubertal range; pelvic ultrasonography is also not indicated. Bone age may be slightly advanced by 6 to 12 months, but advance of 2 or more years is rare, and ordering a bone age x-ray should be left to the discretion of the endocrinologist.

Genital hair appearing in infancy

Appearance of fine hairs in the genital area in the first year of life (typically along the labia in girls and on the scrotum in boys) seems unusual enough to raise suspicion of an underlying gonadal or adrenal disorder. Typically, the phallus is not enlarged, and there is no evidence of growth acceleration. A recent report of 11 infants seen at a mean age of 8 months found resolution in all cases that returned for follow-up [28], whereas the author’s series of 12 such infants found that the genital hair persisted in most. Multiple hormone levels in this series were measured by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry [29]; in half, there was a slight elevation compared with age-matched controls in DHEA-S levels, suggesting this may be a variant form of PA. In no case was 17-OHP levels elevated, but 1 girl, who had had exposure to testosterone because the father was using a topical androgen (Androgel), had a mild elevation of serum testosterone. As for PA and PT, this entity seems to be a benign normal variation, and routine hormonal and imaging studies are not recommended.

Premature menarche

A puzzling situation that can be easily confused with precocious puberty is the onset of vaginal bleeding in a girl who has not yet started to develop breast tissue, referred to as premature menarche. This occurrence may be described as either intermittent light bleeding or daily spotting continuing for many weeks or episodes of heavier bleeding lasting several days and separated by 3 to 4 weeks. Although these episodes are quite worrisome for the family, they almost always resolve over a period of 1 to 4 months. The differential diagnosis includes such potentially serious conditions as tumors, foreign body inserted into the vagina (which would likely result in a more foul-smelling than bloody vaginal discharge), and sexual abuse. However, in the more than 30 cases seen by the author, the physical examination has invariably been normal, the girls have not acted fearful or withdrawn, and none of these worrisome diagnoses have been found. Pelvic ultrasonographic results are normal but may be useful in reassuring the parents if the bleeding persists for more than a month or two. Hormone testing has not in the author’s experience been helpful. The mystery of premature menarche is that one needs estrogen action on the uterus to build up enough endometrium to cause bleeding, but such estrogen exposure should lead to progressive breast enlargement, which is conspicuously absent. There has not been any satisfactory hormonal explanation for this paradox, and nothing new has been published on the subject since the early 1990s.

Central precocious puberty

The diagnosis of CPP should be entertained in girls younger than 8 years who have shown a progressive enlargement in breasts over a period of 4 to 6 months, particularly if accompanied by acceleration of linear growth. It is important to assess breast development by not only inspection but also careful palpation because many chubby girls seem to have breasts while sitting up, but when examined lying down, it is apparent that all or nearly all the tissue under the nipple and areola is adipose. In questionable cases, it is helpful to reexamine the girl in 4 to 6 months to see if the breasts are in fact enlarging because many girls with early breast development have been found to have a nonprogressive or slowly progressive form of precocious puberty, which requires no treatment [11].

Hormonal testing in girls with clearly progressive breast enlargement should be kept simple and may include determining LH, FSH, and estradiol levels, but the LH test is the most reliable for diagnosing CPP. In the past, an increase in LH levels to more than 5 to 8 U/L during stimulation test with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or a synthetic analog of GnRH such as leuprolide was thought to be necessary to confirm the diagnosis of CPP. However, assays for gonadotropins are now more sensitive and specific, and according to a recent study, a single unstimulated LH level of 0.4 U/L or more is sufficient to diagnose CPP in most girls [30]. Prepubertal girls and girls with PT usually have random LH levels less than 0.2 U/L, but some girls with CPP also have low random LH levels, and if the clinical findings are suggestive of CPP, the endocrinologist may perform a GnRH stimulation test. An estradiol level of more than 20 pg/mL is supportive of a diagnosis of CPP, but lower values are sometimes seen in girls who by other criteria clearly are in puberty. Bone age advanced by 2 or more years favors the diagnosis of progressive CPP, but less-advanced bone ages may be seen in patients with CPP of very recent onset.

In boys, the diagnosis of CPP based on physical findings is simpler than in girls, because one will see enlargement of the testes (≥3 cm in diameter or ≥6 mL in volume), reflecting increased gonadotropin secretion, as well as growth of the stretched penis to more than 8 cm in length because of increased testosterone levels, generally more than 50 ng/dL, can be seen. If the testes are prepubertal and pubic hair is the main finding, the diagnosis is likely to be PA, which does not require any intervention.

Which children with CPP benefit from treatment?

In November 2007, representatives of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology met to develop consensus guidelines for the use of GnRH analogs (GnRHas) in children, which were published in Pediatrics in 2009 [31]. One key point was that progressive pubertal development and growth acceleration should be documented over a 3- to 6-month period before starting GnRHa therapy, unless a girl is already at Tanner 3 or greater for breast development, in which case an observation period may not be necessary. There was also consensus that the most compelling reason to treat CPP was to prevent compromise of adult stature because of early closure of the epiphyses; however, it has been found that many girls with the slowly progressive form of CPP achieve a normal adult height without treatment [11]. Long-term follow-up studies have shown that the greatest gain in adult height versus that predicted at the time of diagnosis (average of 9–10 cm with much variation among different studies) is seen in girls with onset of puberty before age 6 years, who make up only a small proportion of girls evaluated for precocious puberty. Some girls with onset of puberty between ages 6 and 8 years achieve a modest improvement in adult height with treatment, but an Israeli study found that treatment of girls whose puberty started at ages 8 to 9 years did not improve adult height compared with that predicted based on bone age [32]. At diagnosis, many girls with CPP are quite tall, so that even though the bone age is advanced and growth will be completed at an earlier than normal age, adult height will usually be within the normal range. Thus, parents of a tall girl with early puberty should not be advised that treatment is needed to prevent their child ending up abnormally short.

The greatest concern of many parents of girls with CPP is the potential psychological effect of early menses. The consensus statement points out that using GnRHas solely to delay menses or to alleviate the consequences of a girl being more physically developed than her peers has not been convincingly shown to improve psychological outcomes [31], although controlled studies addressing this issue are lacking. Girls who start puberty at age 8 years or later rarely reach menarche before age 10 years, and according to the author’s experience, few experience severe stress, particularly if a parent has discussed this with them ahead of time. Girls with developmental delay sometimes have more difficulties in this area and may benefit from treatment to delay menses, although the use of inexpensive alternatives, such as extended use of combined oral contraceptive, which can be interrupted every 3 months to allow less-frequent periods, or medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) given intramuscularly every 3 months, should be considered before using GnRHas [33]. For girls starting puberty before age 7 years, which progresses rapidly, there is a good chance that menarche will occur by age 9 years, which is often very stressful for both the child and mother, and many parents opt for treatment to delay menses. For girls in whom puberty starts between age 7 and 8 years and progresses, advising the parents on how to prepare the child for early menarche sometimes results in a lower stress level than undertaking a course of treatment to suppress puberty with its frequent injections and follow-up visits.

Most cases of CPP are idiopathic and many seem to be inherited. In an Israeli study that included 156 children (mostly girls) with CPP, 27.5% were thought to have a genetic basis, with most inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with incomplete penetrance [19]. The proportion of patients with CPP because of a central nervous system (CNS) lesion is low but varies a lot from study to study. The question of whether all girls with CPP require a brain MRI to rule out CNS lesions (astrocytomas, gliomas, hamartomas, or cysts in the area of the pituitary or hypothalamus) is controversial. One study from Paris found abnormal brain imaging in 19% of girls with onset of CPP before age of 6 years but in only 2% of those with onset between the ages of 6 and 8 years [27]. Although many endocrinologists in the United States do not routinely perform MRIs in all 6- to 8-year-old girls with CPP, European endocrinologists are more likely to do so. The consensus conference on the use of GnRHas concluded that all boys with CPP (in whom the incidence of CNS lesions is higher) and girls with onset of puberty before age 6 years require an MRI of the head, whereas for older girls, those with neurologic findings (eg, severe headaches) and those with very rapid progression are more likely to have intracranial pathology [31].

How is CPP treated?

GnRHas acutely stimulate LH and FSH secretion, but when given chronically, these hormones shut off pituitary gonadotropin and estradiol production because the gonadotrophs are programmed to respond to pulses of GnRH secreted by the hypothalamus every 1 to 2 hours and are desensitized by continuous exposure. The most widely used preparation in the United States is Lupron Depot, a slow release form of leuprolide, which is administered by intramuscular injection every 28 days. The typical starting dose is 7.5 mg, with a current average retail price of $9500 per year. Some patients require larger doses or more frequent administration for complete gonadotropin suppression; for the higher 11.25-mg dose given every 4 weeks, the cost comes to about $18,000 per year. There have been pediatric studies of 3-month formulations of Lupron Depot, approved for women with endometriosis and men with advanced prostate cancer. One study suggested that the 11.25-mg dose works as well in most patients as the 7.5-mg monthly preparation for clinical suppression of pubertal development [34]. Suppression of stimulated gonadotropin levels was not as complete, but there was no difference in sex steroid levels in patients on the 2 different regimens. Although the medication itself is very safe, up to 5% of patients develop painful swelling at the site of the injection. Girls who have started menstruating sometimes have 1 additional period before they stop, after which menses do not resume until at least 6 months after the medication is discontinued. In most cases, there is a decrease in the amount of glandular breast tissue within a few months, but slowing of the rapid growth rate may take a few months longer. Treatment is typically stopped at 10 to 11 years of age.

There is now another therapeutic option for girls with CPP, which is a subcutaneous implant of the GnRHa histrelin, called Supprelin, which slowly releases active medication for 12 months [35]. Clinical trials have shown it to be at least as effective as the injectable formulations, with the main disadvantage being the need to have the implants placed (and a year later removed) by a surgeon, typically under localized or light general anesthesia.

Long-term follow-up studies, summarized in the consensus statement, indicate that treatment with GnRHas have no consequences on reproductive function [31]. The time from end of treatment to onset of menses is quite variable and averages about 16 months. Regular cycles occur in the same proportion as in the general population, and no increase in the rate of infertility has been reported. Bone mineral density has been found in some studies to be decreased during treatment, which is expected because of the loss of estrogen effect on bone mass accrual, but after cessation of therapy, bone density normalizes and there is no long-term effect on peak bone mass achieved.

Gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty

A small proportion of boys and girls presenting with signs of progressive pubertal development have conditions in which the production of sex steroids is independent of increasing gonadotropin secretion. All these conditions are rare, and so individually they do not merit detailed discussion. This section focuses on the red flags that might point to one of these conditions, which can then be promptly referred to a subspecialist for further evaluation.

Girls

Estrogen-producing ovarian tumors are characterized by rapid progression of breast development and growth acceleration, accompanied by very high levels of estradiol (often >100 pg/mL) and suppressed levels of LH and FSH. The same scenario can be seen in McCune-Albright syndrome, which may be suspected on the basis of cystic bone lesions (polyostotic fibrous dysplasia) and irregular café-au-lait areas of skin pigmentation. In some cases, vaginal bleeding may precede breast development but usually before 3 years of age, younger than in most patients with premature menarche. Young girls with virilization, the most obvious sign of which is clitoral enlargement (often more impressive than the amount of pubic hair), need prompt evaluation to rule out the rare androgen-producing adrenal or ovarian tumor or nonclassical CAH. On the other hand, isolated stable clitoral enlargement without pubic hair or growth acceleration is usually a normal variation. In many cases, it is the skin of the clitoral hood, and not the clitoris itself, which is prominent and gives the impression of clitoromegaly. The appropriate screening laboratory test results for girls with an enlarged clitoris and evidence of growth acceleration are testosterone, 17-OHP, and DHEA-S levels. Imaging studies of the adrenal gland or ovaries may be ordered by the endocrinologist after review of the physical and hormonal findings.

Boys

Rapid and/or very early growth of the penis and pubic in a young boy without significant testicular enlargement is the major clue to GIPP. In the days before newborn screening for CAH was widespread, nonsalt-wasting CAH was a relatively common cause of GIPP in boys but is still seen in states and countries that do not perform newborn CAH screening. Leydig cell testicular tumors can also present this way, with the major clue being asymmetry on the testicular examination. Familial male precocious puberty presents at 2 to 3 years of age with adult levels of testosterone and suppressed gonadotropins; the cause is an activating mutation in the LH receptor. Because this condition is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, family history taking may be very helpful. Testes are slightly enlarged because of Leydig cell hyperplasia, which is also the case when precocious puberty is caused by ectopic tumors (typically CNS germinomas or thymic tumors) secreting human chorionic gonadotrophin, which has LH-like actions on the Leydig cells. In any of these situations, the presence of high testosterone levels (usually >100 ng/dL) with low LH and FSH levels is sufficient evidence to request that the patient be seen promptly by a subspecialist.

Environmental exposures to sex steroids

In the past 10 years, there have been a modest number of case reports and small case series describing young boys and girls who develop either rapid genital enlargement with pubic hair or breast development as a result of skin contact with a parent using topical androgens (Androgel) [36] or estrogen creams, so asking about the use of these preparations is important. Testosterone or estradiol levels are variably elevated (with prepubertal LH and FSH), depending on the timing of the most recent exposure.

Summary

Children who present with signs of early puberty require a careful history taking and physical examination and review of the growth chart looking for evidence of recent growth acceleration. The benign normal variations reviewed in this article are significantly more common than CPP, at least in the United States. Why there seems to be large differences in the incidence of PA between the United States and the other parts of the world should be the subject of further research looking for environmental and/or genetic factors. Ordering multiple hormone tests and radiography before having the child evaluated by a subspecialist should be resisted, unless there is clear evidence of rapid progression of findings over the previous 6 months (eg, a girl who presents before age 8 years with Tanner stage 3 breast development or a boy younger than 9 years with penis and/or testicular enlargement). Even girls diagnosed with CPP often do not require treatment because many have the slowly progressive form that does not result in early menarche and compromise of adult stature. In addition, studies suggest that the benefit of treatment in terms of preservation of normal adult stature is clearest for the minority of patients who have onset of CPP before age 6 years, and those girls whose onset of puberty is early but at age 8 years or more do not benefit from treatment with an increase in adult stature.

References

[1] P. Kaplowitz. Precocious puberty: update on secular trends, definitions, diagnosis, and treatment. Adv Pediatr. 2004;51:37-62.

[2] E.J. Susman, R.M. Houts, L. Steinberg, et al. Longitudinal development of secondary sexual characteristics in girls and boys between ages 91/2 and 151/2 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(2):164-173.

[3] W.A. Marshall, J.W. Tanner. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291-303.

[4] M.E. Herman-Giddens, E.J. Slora, R.C. Wasserman, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505-512.

[5] P.B. Kaplowitz, S.E. Oberfield. Reexamination of the age limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in the United States: implications for evaluation and treatment. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4):936-941.

[6] T. Wu, P. Mendola, G.M. Buck. Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):752-757.

[7] F.M. Biro, M.P. Galvez, L.C. Greenspan, et al. Pubertal assessment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed longitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583-e590.

[8] L. Aksglaede, K. Sørensen, J.H. Petersen, et al. Recent decline in age at breast development: the Copenhagen Puberty Study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e932-e939.

[9] H. Ma, M. Du, X.-P. Luo, et al. Onset of breast and pubic hair development and menses in urban Chinese girls. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):e269-e277.

[10] M.A. McDowell, D.J. Brody, J.P. Hughes. Has age at menarche changed? Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:227-231.

[11] M.R. Palmert, H.V. Malin, P.A. Boepple. Unsustained or slowly progressive puberty in young girls: initial presentation and long-term follow-up of 20 untreated patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(2):415-423.

[12] M.E. Herman-Giddens, L. Wang, G. Koch. Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: estimates from the national health and nutrition examination survey III, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(9):988-989.

[13] K. Sørensen, L. Aksglaede, J.H. Petersen, et al. Recent changes in pubertal timing in healthy Danish boys: associations with body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):263-270.

[14] P.B. Kaplowitz. Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S208-S217.

[15] J.M. Lee, D. Appugliese, N. Kaciroti, et al. Weight status in young girls and the onset of puberty. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):e624-e630.

[16] J.M. Lee, N. Kaciroti, D. Appugliese, et al. Body mass index and timing of pubertal initiation in boys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(2):139-144.

[17] L. Aksglaede, A. Juul, H. Leffers, et al. The sensitivity of the child to sex steroids: possible impact of exogenous estrogens. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(4):341-349.

[18] T.D. Nebesio, O.H. Pescovitz. Historical perspectives: endocrine disruptors and the timing of puberty. Endocrinologist. 2005;15(1):44-48.

[19] L. deVries, A. Kauschansky, M. Shohat, et al. Familial central precocious puberty suggests autosomal dominant inheritance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1794-1800.

[20] R.L. Rosenfield, R.B. Lipton, M.L. Drum. Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):84-88.

[21] P.B. Kaplowitz. Clinical characteristics of 104 children referred for evaluation of precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(8):3644-3650.

[22] L. Ibanez, R. Jiminez, F. de Zegher. Early puberty-menarche after precocious pubarche: relation to prenatal growth. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):117-121.

[23] J.B. Armengaud, M.L. Charkaluk, C. Trivin, et al. Precocious pubarche: distinguishing late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia from premature adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(8):2835-2840.

[24] Desalvo D, Mehra R, Vaidyanathan P, et al. In patients with premature adrenarche, bone age advancement by 2 or more years is relatively common and generally benign. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. Denver (CO), April 30–May 3, 2011.

[25] M.M. Van Weissenbruch. Premature adrenarche, polycystic ovary syndrome and intrauterine growth retardation: does a relationship exist? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14(1):35-40.

[26] L. De Vries, A. Guz-Mark, L. Lazar, et al. Premature thelarche: age at presentation affects clinical course but not clinical characteristics or risk to progress to precocious puberty. J Pediatr. 2010;156(3):466-471.

[27] M. Chalumeau, W. Chemaitilly, C. Trivin, et al. Central precocious puberty in girls: an evidence-based diagnosis tree to predict central nervous system abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):139-141.

[28] T.D. Nebesio, E.A. Eugster. Pubic hair of infancy: endocrinopathy or enigma? Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):951-954.

[29] P. Kaplowitz, S. Soldin. Steroid profiles in serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in infants with genital hair. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20(5):597-605.

[30] C.P. Houk, A.R. Kunselman, P.A. Lee. Adequacy of a single unstimulated luteinizing hormone level to diagnose central precocious puberty in girls. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):e1059-e1063.

[31] J.-C. Carel, E. Eugster, A. Rogol, et al. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e752-e762.

[32] L. Lazar, R. Kauli, A. Pertzelan, et al. Gonadotropin-suppressive therapy in girls with early and fast puberty affects the pace of puberty but not total pubertal growth or final height. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2090-2094.

[33] A. Albanese, N.W. Hopper. Suppression of menstruation in adolescents with severe learning disabilities. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(7):629-632.

[34] A. Badaru, D.M. Wilson, L.K. Bachrach, et al. Sequential comparisons of one-month and three-month depot leuprolide regimens in central precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(5):1862-1867.

[35] E.A. Eugster, W. Clarke, G.B. Kletter, et al. Efficacy and safety of histrelin subdermal implant in children with central precocious puberty: a multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(5):1697-1704.

[36] G.J. Kunz, K.O. Klein, R.D. Clemons, et al. Virilization of young children after topical androgen use by their parents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):282-284.