Developing Leadership in Global Child Health

Twenty years ago, when I (the author, K.C.) was a young medical student, a little girl asked the group of us who were working in rural Malawi, “Why can you who have so much not help us who have so little?” Twenty years ago, the challenge was identifying health as an issue. I remember speaking at a meeting of leaders in Malawi in the late 1990s about the specter of HIV/AIDS affecting both men and women, and was told that the disease was something seen only in Western countries.

Around the world, we have seen a large transformation occurring in the attitudes toward health, with a significant push made by governments and leading philanthropic organizations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the One Foundation, led by the rock star Bono. These visible leaders have put global health into the conversation of important priorities, especially in developing countries.

Yet despite a 30% decline in childhood deaths around the world from 1990 to 2009, the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) still reports 8.1 million deaths in children under the age of 5 in 2009 [1]. Approximately 70% of these deaths are preventable by available knowledge and technology [2]. Therefore, 5.5 million deaths in children can be prevented by what we know and have available to us. These simple questions still exist: Why do these deaths occur when we know how to prevent them? How can we reduce the gap between our knowledge base and our actions leading to these poor health outcomes?

Obviously there is a large gap between what is known and what is done to improve global child health. One of the issues is how do we make these solutions, visible, viable, and acted upon? The challenge is not just to review the state of where global child health is, but to provide fresh, new insight into possible solutions. The missing gap is something that is not discussed in many medical or public health schools, but something we find in business and management schools: leadership. My belief is that the major weakness is a lack of global child health leadership globally, nationally, and locally that prohibits faster improvements in morbidity and mortality.

What is known about global child health leadership? The unfortunate answer is: not very much.

This article looks at the realm of global child health leadership and examines prior attempts to reduce mortality and morbidity. The philosophy and outlook at building global child health leadership currently being developed between sub-Saharan Africa and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto is highlighted. Examples are provided of concrete programs and efforts being worked upon to develop this global child health leadership capacity. The author hopes to inspire more participation in building global child health leadership.

First, a brief survey is given of global child health programs: Primary Health Care, the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses, and Millennium Development Goal #4.

Primary health care

In 1978, Primary Health Care (PHC) was launched at Alma Ata with the slogan “Health for All by the Year 2000” [3]. PHC aimed to create national health systems, based on the economic abilities of each country [4]. The type of health care employees would be dependent on each country’s goals and resources available.

The specific Alma Ata declaration aimed to increase the participation of community members in the development of health care, and aimed to decentralize health care to individuals at a local level [3].

The key principles can be summarized as follows: (1) PHC aimed to promote equity within health care; (2) community participation was paramount at all decision-making points; (3) prevention was highlighted over cure; (4) available technology should be used; (5) other sectors should be involved in health care (such as education, agriculture and housing); (6) decentralization of decision-making was important; and (7) leadership was needed to achieve the goals of PHC [5].

Therefore, as far back as 1978 it was clear that global health leadership was a basic requirement to achieving health for all people. However, although there were programs to “train” health leaders, there was little systematic development that targeted national or local leaders effectively.

The integrated management of childhood illnesses

In the mid 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF adopted the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI). IMCI builds on the concept of PHC, using the community health worker (CHW) as the cornerstone of assessing a child’s well-being. If a sick child presents to the CHW, the CHW decides how to best treat a child, using a color-coded system with red (danger), yellow (caution), or green (safe) to determine whether a child should be managed at home or in hospital.

IMCI has other foci including improving the training of CHWs, strengthening preventive health care measures, and upgrading existing health care services. It provides a first-line approach to treating child health problems. Although IMCI has been a standard of care, its proper adoption has been a challenge.

The Millennium Development Goal #4: reducing child mortality

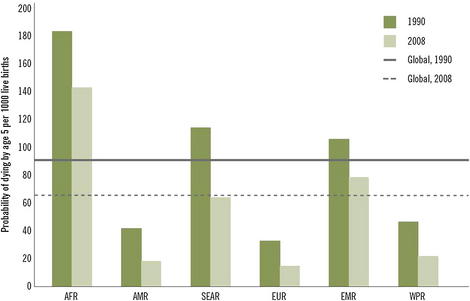

The fourth Millennium Development Goal (MDG #4) is to reduce the under-5 mortality rate by two-thirds from 1990 to 2015 [6]. We have seen the number of children dying from developing countries decrease from 100 (1990) to 72 (2008) deaths per 1000 live births, with only 10 of 67 countries with high child mortality on track to meet the MDG target [7]. The continuing challenge, however, has been the slow decline in childhood deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, with high fertility rates and a slow reduction in under-5 mortality rates (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Mortality rate in children younger than 5 years by WHO region.

(Reprinted from www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS10_Part1.pdf, p. 13; copyright The World Health Organization; with permission.)

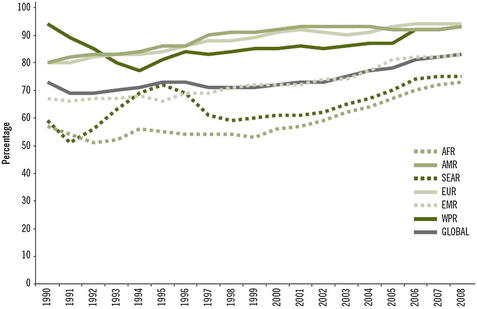

Other associated MDG #4 objectives include reducing the infant mortality rate, and increasing the proportion of 1-year-old children immunized against measles (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Measles immunization coverage among 1-year-olds by WHO region.

(Reprinted from www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS10_Part1.pdf, p. 14; copyright The World Health Organization; with permission.)

There are obvious trends downward in the number of childhood deaths. There have been large falls in under-5 mortality rates across all areas of the world, but because of high fertility rates, there has been little progress in overall numbers of childhood deaths in sub-Saharan Africa [7].

Why are we failing to reduce child deaths faster?

As far back as David Morley’s classic textbook on global child health, Paediatric Priorities in the Developing World, there was widespread recognition that improvements in children’s health were not strictly rooted in medical answers [8]. The challenge is that many of the underlying root causes of child deaths are not simple and straightforward medical causes that health professionals tackle on a daily basis. For example, poverty, poor female education, and poor water and sanitation remain barriers to successfully reducing childhood mortality.

The challenge in children’s health is but one small portion of a government’s list of competing priorities. Child health competes with adult health; health competes with other departments, such as defense, industry, education, transportation, and agriculture for limited government resources. Improving children’s health requires both technological improvements in tackling children’s diseases, and providing enough funding and resources to deliver proper services.

Regarding the solution to global child health mortality, the technical aspects are not the problem as much as access to health care. For example, one area where there has been little reduction in global child mortality in the past decade has been on perinatal mortality. The challenge remains in identifying mothers who will run into trouble, getting access to the right level of care, and ensuring the quality of care once they arrive at the facility [9].

Our current global child health leaders continue to face a combination of economic, policy and political challenges to improve health systems and health outcomes for children. In particular, a cadre of child health leaders who can advocate for children and policy change should be developed in the existing health care system. Leveraging existing collaborative networks, such as the Program for Global Pediatric Research, can bring together child health leaders from Africa and around the world to forward the global child health agenda [10].

It is with this in mind that the author now looks at leadership as an integral part of developing global child health programs.

What is leadership?

There is great difficulty in defining what leadership is. Is it experience? Is it logic? Is it vision? Pulitzer Prize winner James MacGregor Burns, in his influential book Transforming Leadership, aptly states: “I have come to see leadership not only as a field of study but as a master discipline that illuminates some of the toughest problems of human needs and social change” [11]. The reality is that leadership occurs at various levels, both from positions of power and from individuals at the grassroots level.

Leaders such as Gandhi in India, Mao Tse-Tung in China, and Alexander the Great are well-known leaders who helped transform countries and societies. The question is whether the intrinsic characteristics of an individual, the “Great Man” theory proposed by Sidney Hook, “creates” leadership through the natural intellect and strength of character [12]. Countervailing ideas suggest that leadership may be a product of time and circumstances, and by decisions made at opportune times. This idea was championed by Karl Marx [13] and later by the philosopher, Herbert Spencer [14]. In particular, Spencer championed the concept that complex influences were what created the conditions by which leaders, through a Darwinian process, would succeed through the creation of wealth and power. So the concept of a great leader was hypothesized either to be intrinsic to the leader oneself, or a concept dependent on the circumstances and the situation. Thus, leadership can also occur at local levels around specific issues that lead to direct activism, such as protecting women from being sexually exploited or by protecting a local park or forest from being harmed.

The development of the program for global child health leadership comes from a perspective that leadership qualities, characteristics, and traits can be maximized, and specific situational opportunities identified to improve global child health.

Leadership begins with “vision”: what is the purpose and goal we seek? Leadership provides purpose to an idea or goal. However, vision is insufficient. Leadership should bring components such as logic and pragmatic approaches that can be performed in a systematic fashion. There are also some basic characteristics that are important for a leader to bring to the fore, such as integrity, adherence to principles and values, humility and respect for others, communication, and the ability to persuade people and demonstrate commitment to the vision. Experience often helps in leadership, but it may act as a barrier if preconceived notions limit the capacity to invoke change.

What does leadership in global child health mean?

Before 2000, global child health leadership was provided internationally by UNICEF and the WHO. There were many local champions of child health, but little systematic training of these leaders.

There are 3 fundamental components of global child health leadership. First, there must be recognition that children have increased morbidity and mortality around the world. Second, it is important to work out how to make the problem a priority issue, facilitating resources and funding. Finally, it is important to identify the means and methods to address problems and resolve issues, and communicate how to effectively promote constructive change.

There are cross-cutting themes that exist no matter what level of health care provider and leader is sought. These themes include: identification of problems and issues; setting policy priorities and agendas; communication; team building; managing conflict and change; understanding and interacting with the political system; building health capacity; and conducting health system planning at the district, national, and international levels.

The goal of training global child health leaders is to develop a cadre of individuals who can effect positive change and help shape policy within the existing and future health care systems. Leveraging on large-scale collaborative networks around the world can help advance the skills and agendas of global child health leaders. The aim is to create agents of change and advocates for children’s health issues.

What do we know about health leadership in developing countries?

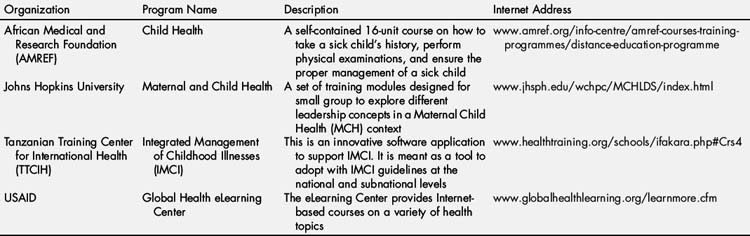

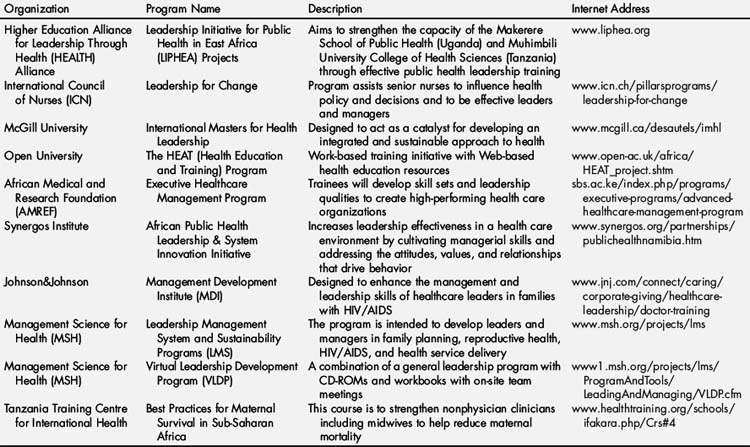

Although there is a broad recognition of the need to develop health leadership, there is very little information on systematic training for health leadership. A review of PubMed and a Google search revealed the several global child health leadership programs (Table 1) and global health leadership programs (Table 2).

There is a surprising paucity of concrete leadership training programs that help train global child health leaders. Most programs do not present an organized approach to training leaders.

The hospital for sick children and developing a leadership program in global child health

In 2009, The Hospital for Sick Children was given a grant by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) to develop a leadership program in global child health. The grant was to help developed leadership programs in global child health in 3 countries, namely Ghana, Ethiopia, and Tanzania, with very different leadership requirements. Ghana’s leadership program focuses on pediatric nursing leaders; Ethiopia’s program focuses on building academic leaders; and Tanzania’s leadership program focuses on developing maternal and child health community leaders.

With these varying requirements, there exists a large challenge in finding a core set of values, skills, and principles to teach leaders.

This section highlights some thought processes in developing a leadership program in global child health. Although some steps seem basic, the combination of these steps will help develop and enhance the skills of leaders to forward the child health agenda. The basic modules in global child health are highlighted.

Identifying the scope of the problem

One of the first aspects of the training program is the need to develop basic concepts and understanding of epidemiologic conditions on health, including the understanding of how to survey and collect data on health conditions for an area. Although the scope of the course does not outline the details of how to survey and collect mortality and morbidity data, the aim is to outline basic epidemiologic concepts for child health, including verbal autopsies to identify causes of death; create and understand neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality rates; identify disease outbreaks, including proper water and sanitation sources; highlight health care access points to identify where populations can get primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of health care, including basic health practices such as immunization and maternal and perinatal health care; and identify the population’s health care knowledge, understanding, and practices. The goal for the trainee is not necessarily to conduct all of these surveys, but to understand how to gather, organize, and understand information collected from the field, and to recognize gaps in knowledge and understanding in child health.

Identify personalities, motivations, and skills

The second module assesses a participant’s personality, sources of motivation, natural skills, and areas that may require development. The concept comes from the Meyer Briggs personality test, which is a standard assessment tool for many leadership training courses [15]. The module aims to make participants appreciate different personality types, how to work and communicate with different personality types, and how to use their natural skills and minimize potential conflicts.

Creating vision

In the first 2 modules the importance is established of collecting baseline information and understanding the situational context in developing programs by identifying the scope of the problem, and providing an evaluation of the people who will be working in the process. In this third module, the aim is to teach how to create vision.

Vision is looking at the larger picture and imagining what can be achieved in the future through enabling possibilities, and enlisting others to participate in their own dreams through shared goals and aspirations. However, it is insufficient to create vision without a means to achieving these aims.

Vision should take into account the aspirations and goals of each stakeholder to ensure that each stakeholder’s wishes are achieved, or to minimize opposition to a project or proposal. It should also take into account reasonable short-, medium-, or long-term frames to meet each stakeholder’s goals and clarify who is responsible for achieving each goal.

Vision should also stretch the goals of individual members, to take them out of comfort zones and push their capabilities.

In the context of global child health, the aim may be to develop a global child health program, to strengthen the overall health system to deliver a package of goods, or to promote collective advocacy to highlight a shortfall (such as perinatal care) at the global level. Successful vision development, however, allows as many stakeholders as possible to participate in the engagement process, and involves as many parties as possible in a concrete, focused objective that is measurable and achievable.

Communication

One of the most important skills to develop is the ability to communicate effectively with other team members, stakeholders, clients, and the public. There are various methods of communication including reflective listening, verbal communication through the media and press, and presentations such as video, social media, and Powerpoint. There are also important nonverbal communication clues to observe and act upon.

It is important that roles are clearly defined, yet sufficiently flexible to adapt to changing circumstances. It is also important that the environment created enables members to maximize their potential and to come up with new and creative ideas.

Communication should allow honest views, opinions, and feelings. In many cultures this may not be the norm, and may take time to develop. However, there should be means by which team members can communicate their feelings if open forums do not allow their opinions to be heard.

The other important aspect of communication is providing feedback. The key in providing feedback is to be as objective as possible, and to be positive and constructive. Often feedback is seen as being highly critical; however, when provided in a positive, constructive way, it may help enhance and energize fellow team members.

Team building

Leadership requires followers to help deliver the message and to perform the tasks that help make the vision reality [16].

To build a successful team, several things are important. The values and vision should be aligned for all team members, so that they can work together effectively. Roles should be clearly defined and a supportive environment created. Meetings and gatherings should be focused, with clear implementation and outcome goals. Decisions should be discussed and agreed upon by the members of the team, allowing for dissention, but ultimately agreeing on a common pathway to achieve the vision. There should be a clear timeline and pathway for deliverables, with focused, measurable achievements. Individual goals should challenge each individual team member to achieve to the best of their ability.

One of the other important aspects is for constant feedback and examination of ways to improve how effectively the team works together. There should also be an analysis by which team members look at how their working relationship interacts with their fellow team members and with other people that may be involved with their organization (including patients, clients, suppliers, and the public).

Some characteristics of successful teams include strong individual initiative, including team members making suggestions, and volunteering to solve problems; finding creative ways to resolve disputes, and developing consensus on complex issues; open communication between team members, including anticipating and communicating about potential problems; allowing members to lead at different times depending on the task to be completed; frequent social exchange and little hesitation in expressing concerns; maintaining calm even in the face of significant problems; and positive constructive encouragement and honest feedback throughout the process.

Edgar Schein highlighted how leaders convey to their teams, their beliefs, values, and assumptions through 6 primary mechanisms [17]:

Team building is one of the most difficult aspects to implement, especially in hierarchical societies, but it is helpful to build consensus and sustainability in projects. Without broader buy-in, projects can build up and dissipate relatively quickly; however, with buy-in, people get broader-based ownership of an idea and sustain a program over time.

Managing conflict and change

Edgar Schein, one of the great management thinkers of the twentieth century, in his influential book Organizational Culture and Leadership, highlighted the intrinsic biases that leaders bring to their organizations by imposing their beliefs, values, and assumptions on other members of the group [17].

Conflict occurs in all manners of leadership. One of the key aspects in addressing conflict is to effectively listen to the problem at hand before attempting to find a resolution to the problem. If the problem is between team members, open communication is necessary between both sides to resolve any conflict. If the problem is between leaders and their team it is necessary to clearly identify the problem, seek resolution, or to find amicable ways to part.

Change is an inevitable part of organizations. Change occurs through various stages: (1) introduction and growth; (2) maturity; and (3) decline. During each of these stages, organizations may face different types of challenges to change and adopt different approaches.

Often change cannot be anticipated, especially by external outside forces [18]. However, if change is anticipated, one should try to be proactive and fix things ahead of time. Positive change can occur when recognition of opportunities occur. To recognize these opportunities, it is important to look at resource capabilities but also to interact with customers, suppliers, team members, and the public to increase awareness of existing opportunities. Change should happen incrementally and be clearly understood by all key stakeholders. It does not have to be quick and sweeping. Rapid changes can lead to confusion, and a lack of clarity of mission and purpose. Change should also attempt to provide the best outcomes for any given resources, and should focus on the present situation and not only look to the future. If change fails to address current issues, change is unlikely to be sustainable.

The politics of health

Health and health care remain one of the most contentious areas of any government. The first part of this module focuses on recognizing how health competes with other sectors of government for priority standing. This approach includes both financial and public policy support at the various government levels and how this translates into both fiscal and nonfiscal resources developed by health.

The second part focuses on how to practically make a local vision sustainable, and how to broaden the vision to a state, national, regional, or international level. For example, malaria bed netting was tested in the 1990s in Tanzania. After research showed its benefits, it was publicized nationally and internationally, and local companies began producing malaria bed nets for use through East Africa. The international accolades played an important role in influencing and adopting malaria bed nets in Africa.

Building health capacity and health system planning

So how do we tie this all together for global child health leadership? The first module focuses on obtaining an understanding of the diseases, problems, and underlying health conditions of the area that is being served. The module focuses on acquiring facts that can help shape decisions and provide information to the leader in question. It does not focus on the “how to,” but on what to do to try and elicit information and what to do once information is available.

The second module focuses on looking at the actors in the program. What are their underlying characteristics and motivations? The module focuses on how to engage different individuals, and listen, shape, and change their thoughts and motivations to make them align with the leader’s goals and objectives. Understanding individuals and what shapes their desires is important in getting them to buy into the vision.

The third module focuses on the development of the vision. Using the best available information and recognizing the players involved in the situation, how can we create a collective vision congruent with a leader’s personal vision, and recognize potential barriers and harms that may make the vision unachievable? For example, Bill Clinton’s health care vision to provide health care to every American was a wonderful vision, but ended up having significant barriers because of the opposition from health care associations, Health Maintenance Organizations, businesses, and leaders from the pharmaceutical industry. Failing to recognize how the different actors would react led to its general downfall.

More successfully, the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines, led by Médecins Sans Frontières, brought together HIV/AIDS organizations and health leaders of developing countries, and with public health pressure forced governments and drug companies to allow cheaper generic drugs to replace more expensive developed-country drugs. Vision, when combined with a focused message, clear goals, and simple steps to achieving outcomes, works best.

The fourth module focuses on communication needs. Communication occurs at many different levels, within and outside the organization. There are verbal, written, and nonverbal communication skills essential for any leader. Establishing clear lines of communication and being aware of back-channel talking is important to being an effective leader.

The fifth module looks at the concept of the team, and building teams to work effectively to turn vision into reality. It emphasizes that successful teams have great communication, various expertise, and different people who can effectively lead at different times. The role of the “leader” in effective teams is to act as a role model, and can help shape and determine the behavior of individual team members. At the same time, effective team leaders listen to their members and facilitate open discussion of novel approaches to address problems.

The sixth module focuses on the times when things are not going well or when change is happening. This time of conflict and change creates problems within team dynamics and may question the capacity and role of the leader itself. The module focuses on getting leaders to address issues of conflict directly and to look at change from a positive fashion, focusing on concrete, incremental changes, rather than bold changes without clear focus.

The seventh module looks at the importance of putting health into a political context. Politics occurs at all levels—regional, national, state, and local. Understanding the different political actors, their agenda, and their perceptions are important in making improvements in global child health a reality.

The final module ties in all the modules looking at the broader vision and looking at the global child health sector, to figure out how this can be integrated in the bigger picture. How do we build capacity in global child health? Although this could be seen as a “what do we want in the future” exercise, the constant challenge is, given our current and future resources and our current skill level and expertise, how can we best use it to obtain the “best” health outcomes?

The concept is to create health planning, by looking at trade-offs between areas that can potentially grow quickly to improve health, or be eliminated if there is little evidence of health impact. The aim is to improve health conditions over time. The module looks at the alignment between current personnel and health delivery, services, and outcomes, and identifies areas of weaknesses and gaps in knowledge and the means to address them. It compares the potential impact of financing health directly versus collaborating with other political entities, such as improving maternal education through the Ministry of Education, or improving roads through the Ministry of Planning or Infrastructure. Finally, it emphasizes the use of different tools, including using political pressure, media, and developing collaborations with other organizations, to translate the underlying vision into reality.

The goal of this module is to strengthen health planning and health capacity building, by emphasizing creative vision-building to promote global child health by all means possible.

How do we turn the training into the global child health reality?

The Leadership Training Program in Global Child Health aims to provide each trainee with the following skills.

The ability to collect and understand epidemiologic data in global child health

At the most basic level, the leader should develop the means, techniques, and understanding of how to gather the best information available, and interpret the meaning of these data.

Formulate a plan to address priority areas

Leaders will be expected to have the capability of forming teams, identifying people’s strengths, create common goals and vision, and articulate a clear plan to address priority areas. Part of the process must be the ability to communicate not only internally but externally, the wanted and desired goals, and the road map to achieve them. Furthermore, the ability to anticipate and adapt to challenges is important.

Create a sustainable plan

A successful program will sustain itself through financial and nonfinancial means. There will be a combination of human resource planning, resource acquisition and development, and continued public awareness. The organization will clearly have succession plans, and promote knowledge dissemination to other organizations, government agencies, and international neighbors, if the program is seen to be successful.

Summary

In an era of vast knowledge, when we know what to do to improve children’s health, there is still a massive global failure in preventing mortality and morbidity in millions of children around the world. The author argues that this failure is because we have not developed a cadre of global health leaders that puts child health at the forefront of political agendas nationally and globally.

Unfortunately, we have failed to find, develop, and champion enough of these global child health leaders at the local, national, regional, and global levels. The Sick Kids Global Child Health Leadership program aims to change that, by providing a leadership component combined with global child health care knowledge and understanding. By promoting leadership, we aim to develop champions who can evaluate health care conditions and the quality of personnel, and bring them together to achieve a common goal and vision to improve child health. Only then can we achieve “Health Care for All.”

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Katie Johnson and Leticia Rebello for their work on Tables 1 and 2.

References

[1] Inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. CME info. Available at: www.childmortality.org Accessed November 6, 2010

[2] G. Jones, R.W. Steketee, R.E. Black, et al. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362:65-71.

[3] WHO. Primary health care: report of the international conference on primary health care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September, 1978. Available at: www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf Accessed December 1, 2010

[4] D.E. Bender, K. Pitkin. Bridging the gap: the village health worker as the cornerstone of the primary health care model. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24:515-528.

[5] D. Hillman, E. Hillman, K. Mukelebai. The primary health care manual for East Africa. New York: UNICEF; 1996.

[6] Millennium development goal #4: reduce child mortality. Available at: www.un.org/millenniumgoals/cldhealth.shtml Accessed December 1, 2010

[7] C.J.L. Murray, T. Laakso, K. Shibuya, et al. “Can we achieve Millennium Development Goal 4 (reduce under-five mortality by two-thirds?). New analysis of country trends and forecasts of under-5 mortality to 2015.”. Lancet. 2007;370:1040-1054.

[8] David Morley. Paediatric priorities in the developing world. London: Butterworths Publishing; 1973.

[9] WHO. Integrated management of pregnancy and antenatal complications. Available at: www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/about/impac/en/index.html Accessed March 15, 2011

[10] Programme for global paediatric research. Available at: www.sickkids.ca/PGPR/index.html Accessed March 15, 2011

[11] Burns James MacGregor. Transforming leadership. New York: Grove Press; 2003. p. 9

[12] Sidney Hook. The hero in history: a study in limitation and possibility. Boston: John Day Company; 1943.

[13] Karl Marx. David Fernbach, editor. Marx’s political writings: the revolutions of 1848, surveys from exile, the first international and after, vol. 1–3 (Marx’s political writings). New York: Verso Publishers, 2011.

[14] Herbert Spencer. Illustration of universal progress: a series of discussions. Charleston: Nabu Press; 2010.

[15] Meyer Briggs personality test. Available at: www.personalitypathways.com/type_inventory.html Accessed March 1, 2011

[16] Elizabeth Haas Edersheim. McKinsey’s Marvin Bower: vision, leadership & the creation of management consulting. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2004.

[17] Edgar H. Schein. Organization culture and leadership, 3rd edition. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2004.

[18] Peter F. Drucker. The essential Drucker. New York: Harper Business; 2004.

There are no disclosures of relevance to this study.