Management of Pediatric Intestinal Failure

Patients and families suffering from intestinal failure are exposed daily to physical, emotional, and fiscal burdens that result in an immeasurable amount of distress [1]. Intestinal failure occurs in these patients because of an inability of their bowel to meet fluid and/or nutritional needs required to sustain normal physiology and growth without parenteral nutritional support. In children, short-bowel syndrome (SBS) is the major cause of intestinal failure and results from both congenital disorders and extensive surgical resection. The common causes of SBS include intestinal atresia, abdominal wall defects (primarily gastroschisis), intestinal volvulus, long-segment Hirschsprung disease, complicated meconium ileus, and necrotizing enterocolitis (30% of cases and the most common cause).

Of all pediatric SBS, 80% occurs during the neonatal period. Data on the incidence and mortality related to SBS are sparse. A recent cohort of very low and extremely low birth weight neonates at 16 tertiary centers in the United States demonstrated incidences of SBS at 0.7% and 1.1%, respectively, although this excluded cases in term infants [2]. Given the increase in the overall number and survival of these at-risk patients, it is logical to assume that the overall number of pediatric SBS will continue to increase as well. Mortality in this population of patients occurs in a bimodal fashion, with the first peak corresponding to infants who undergo massive initial bowel resections and a later peak corresponding to complications of SBS, namely central venous catheter sepsis and intestinal failure–associated liver disease (IFALD). Survival rates for children with SBS have been quoted as 73% to 89%, with lower rates in patients requiring chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) [3–6].

Recently, the development of formal multidisciplinary programs has greatly improved the care provided to these patients by reducing both the morbidity and mortality associated with intestinal failure [7]. In general, these programs consist of gastroenterologists, pediatric surgeons, advanced care providers dedicated to intestinal rehabilitation, intestinal failure nutritionists, pharmacists with advanced training in parenteral nutrition (PN), and social workers. As intestinal rehabilitation centers care for children within their institutions as well as accepting numerous referrals both nationally and internationally, administrative support that provides these families and referring physicians easy access to the program is invaluable. This includes access to people who can help provide timely information on how to receive a consult and recommendations from the team, coordinate referrals and transport to the center, and provide continuity of care when they return home. After discharge, ongoing communication with the referring physicians and provision of detailed care plans can avoid many of the complications that contribute to the morbidity associated with intestinal failure.

The care of patients at risk for intestinal failure begins at birth for those with congenital problems and in the operating room for patients undergoing massive intestinal resection. Although the time course of intestinal adaptation predicts that many of these patients will eventually be able to obtain enteral autonomy, waiting for the few patients to declare themselves as having chronic intestinal failure misses an opportunity for prevention. Early treatment paradigms designed to minimize morbidity and establish early controlled feedings will likely benefit all patients at risk by reducing the overall need for parental nutritional support. Decisions made at this time should take into account several key points:

Assessment of the child with intestinal failure

A careful clinical assessment of the child with SBS is invaluable in gauging his or her overall status. Anthropometric data should be obtained frequently and compared with growth curves after adjustment for gestational age. Precise estimates of intake and output are important, as is monitoring of electrolytes, micronutrients, minerals, and trace elements (zinc, calcium, magnesium, copper, manganese, iron, chromium, selenium, and lead), especially in TPN-dependent children. If a surgical resection was performed at a referring institution, the location and type of stomas present is important both for planning reanastomosis and possibly introducing distal mucous fistula feeds. An estimate of the actual length of bowel remaining is helpful and should be recorded as a percentage of expected bowel length. The location and status of any existing central venous access sites should be assessed and a history of any catheter-related infections (CRIs) documented with culture and sensitivity data if available. Studies to evaluate the patency of central veins should be obtained in all patients, as vascular complications from long-term central venous access can limit the ability to provide PN and may be an indication for transplant evaluation.

Aggressive surgical strategies to reestablish intestinal continuity are beneficial in the management of children with intestinal failure. In patients with high stoma output, as commonly seen with proximal jejunostomies, correction of fluid and electrolytes in balance with enteral feeding is not achievable without the benefit of having the distal intestine in continuity. The presence of any defunctionalized loops of bowel should be noted and if possible they should be salvaged at the time of surgery. Before any attempt at reanastomosis, contrast studies should be performed to assess the anatomy of the remnant bowel and to help formulate a surgical plan.

Feeding strategies

The ultimate goal in treating children with SBS is a gastrointestinal tract that can meet the nutritional requirements sufficient to continue growth and normal physiology. This often requires continuous feeds to maximize the percentage of enteral feeds over a 24-hour period. Secure enteral access is required to meet this goal. As many of these patients have difficulty with gastric emptying, evaluating the ability of the patient to tolerate nasogastric (NG) feeds can provide very useful clinical information before placement of a gastric feeding tube (GT). In general, patients who tolerate NG feeds will also tolerate GT feeds. In cases of poor gastric emptying and high residuals, placement of a nasojejunal feeding tube (NJ) provides important additional clinical data regarding the ability of the bowel to tolerate enteral nutrition. If tolerated, placement of gastrojejunal feeding tubes (GJ) will allow distal feeding while simultaneously decompressing the stomach. This also provides a way to start oral feeds in patients with poor gastric motility, as the stomach remains vented. We typically avoid performing antireflux procedures in these patients unless their reflux is a limiting factor in the ability to feed via GJ tube.

In general, all at-risk patients for intestinal failure should be treated using protocols designed to minimize complications and enhance adaptation. Most of these patients will require initial support by PN. At our institution, we have established a lipid reduction protocol that limits the amount of fat to less than 1 g/kg/d in all at-risk patients and we have noted a dramatic decrease in the incidence of elevated direct bilirubin and liver enzymes. In select cases with ongoing elevation of liver enzymes and direct bilirubin, intravenous omega-3 fatty acids (Omegaven; Fresenius Kabi AG, Bad Homburg, Germany) appear to be beneficial [13]. Ongoing prospective studies are evaluating these 2 treatment options and should provide useful data in the near future to help establish data-driven practical guidelines regarding the use of these strategies.

Early initial feeds should be provided continuously using breast milk (mother’s or donor’s) for all infants when available. There are several studies that support the use of breast milk in this patient population for reducing complications associated with SBS [12]. This benefit is likely because of its high levels of immunoglobulin A, nucleotides, long-chain fats, growth factors, and free amino acids, including glutamine present in breast milk. In cases where protein allergies occur, when breast milk is not available, or in older patients, we initially provide an elemental amino acid–based formula.

Advancement of feeds is based on the lack of emesis and abdominal distention, the consistency and amount of stool output, and the presence of skin break down. When the patient experiences feeding intolerance, the feeds should be reduced rather than stopping and restarting all feeds, unless there is evidence of systemic illness or sepsis. In our opinion, the recurrent practice of starting and stopping feeds limits enteral stimulation of adaptation and makes it difficult to identify the amount of enteral feeds that these patients will tolerate. Fluid losses from stoma output and decompressing gastrostomy tubes in the case of jejunal feeds should be carefully measured and replaced mL:mL with an appropriate electrolyte solution. In cases where the stoma output approaches or exceeds 40 mL/kg/d, we consider adding 3% pectin to the formula and frequently use antidiarrheal and antisecretory medication. We do not decrease the rate of feeds in these patients unless there are issues with persistent fluid and electrolyte issues, usually identified by a decreased CO2 below 20 on serum chemistries. We do not check for the presence of reducing substances, as this does not provide useful clinical data in our opinion. One important reason to hold or limit feeds is the presence of skin or perineal breakdown. Local wound care in this population can be very difficult and benefits tremendously from established wound care programs.

Oral feedings in neonates with SBS are typically not begun until the patient is tolerating full continuous feedings. During this time, aggressive occupational and physical therapy are provided to help establish oral motor skills. Holding feeds for 1 hour and offering that omitted volume orally begins the transition from continuous feedings. Initially this is done daily or twice a day and then gradually increased. Parenteral nutrition should be decreased as enteral feeding volumes are increased. In general, we decrease by 1 mL/h for each 1-mL/h increase in enteral feeds. In cases of extremely low birth weight and very low birth weight infants, the inability to provide PN below rates of 2 mL/h and the overall limitation of total amount of fluid volume the patient may receive can make achieving the total amount of calories by enteral nutrition a challenge. In situations where early reestablishment of intestinal continuity is possible, we will opt for improved growth with PN rather than pushing or concentrating feeds until after surgery. It is important to recognize that the short-term goal is not to wean off PN, but rather to establish enteral nutrition with fluid and electrolyte balance that results in normal growth. Many of the complications of PN are greatly minimized when enteral feeding provides greater than 50% of the total needs. Morbidity associated with early weaning of PN such as poor weight gain and intestinal damage or bacteremia owing to high formula concentration or volume is outweighed by the risks of low-volume PN.

Predictors of outcome in intestinal failure

Several retrospective studies have tried to identify certain characteristics that may be useful in predicting outcomes in children with SBS and/or intestinal failure. Given the wide array of diagnoses that can lead to intestinal failure, it is difficult to isolate predictors of outcome, but there are some general trends (Table 1). The length of remaining bowel and its location are the most logical factors to use in predicting a patient’s course with intestinal failure. Neonates have an amazing capacity for adaptation, and this potential is increased in preterm infants [9]. Previous work has shown that patients with less than 10% of their predicted small-bowel length were less likely to wean from PN and they have a higher relative risk of death [5]. This fact makes accurate assessment of small-bowel length at the time of surgery critical for helping to plan a comprehensive treatment regimen and for anticipating complications. The remnant bowel should be measured and documented in the operative notes with each surgical procedure. Using a silk suture along the antimesenteric border of the bowel is a reasonable approach to obtain an accurate length [8].

Table 1 Factors associated with prognosis in intestinal failure

| Positive Factors | Negative Factors |

|---|---|

| High plasma citrulline levels | Remnant bowel length <10% of expected |

| Remnant segments include terminal ileum and colon | Cholestasis (direct bilirubin >2.5 mg/dL) |

| Enteral feeding at least 50% of total needs | Bacterial overgrowth |

| Care in a multidisciplinary program | Loss of the ileum |

| Recurrent sepsis |

In addition to length, the location of the remaining bowel is also important. The jejunum is primarily a secretory segment of the gastrointestinal tract, whereas the ileum possesses more absorptive capacity, as well as participating in vitamin B12, fat-soluble vitamin, bile salt, and fatty acid physiology. For this reason, the ileum has a far greater ability to adapt than the jejunum, and therefore the amount of distal bowel required to become independent of PN is far less then that of the jejunum. In addition, the ileocecal valve prevents migration of colonic bacteria into the small bowel, which can hinder absorption further [14]. The idea that the presence or absence of the ileocecal valve itself is a predictor of potential to wean from PN has been recently challenged. As its loss does not appear to be an independent factor contributing to intestinal failure, a more likely explanation is that it is surgically removed in cases associated with the loss of the ileum. Restoring diverted colon back into the enteral steam provides significant absorptive capacity that is greatly beneficial in the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance. Equally important is the potential for the colon to reclaim energy from the production of short-chain fatty acids (predominantly butyrate) by colonic microbiota that serve as an energy source and enhance fluid absorption as well as providing strong adaptive hormonal signals back to the proximal small bowel to augment absorption and to slow down intestinal transit time [5].

Across several studies, IFALD remains the most likely predictor of a negative outcome and some estimate that nearly two-thirds of children with intestinal failure end up with liver disease at some point during their course [15,16]. Multiple studies have also indicated that increasing levels of direct hyperbilirubinemia (particularly >2.5 mg/dL) are strongly predictive of mortality [5,17,18]. In addition to predicting mortality, bilirubin levels have been evaluated as predictors of progression to end-stage liver disease [19]. The progression of IFALD is aggravated by episodes of sepsis that may result from CRIs. Prolonged peripheral nutrition can result in transient elevation of bilirubin, transaminases, and GGT that resolve after discontinuing PN. In children requiring PN for extended periods, it can result in cholestasis, periportal inflammation, and fibrosis. With ongoing hepatic damage, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and other sequelae of chronic liver disease can result. Extensive ileal resection with loss of normal enterohepatic circulation can further exacerbate this process. Aggressive prevention of IFALD is important, as this is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in these children. It also hinders adaptation in the remaining bowel [20]. The importance of preventing this complication has led to the development of PN protocols designed specifically to protect the liver, as discussed previously, with the basic premise of these strategies being lipid reduction.

Along with physical characteristics of the bowel, there are several systemic indicators of a patient’s course with intestinal failure. A predictive marker would be useful to stratify children and identify earlier those who might benefit from expeditious evaluation for intestinal transplantation [2,18,21,22]. Plasma citrulline levels have been investigated as a surrogate for functional enterocyte mass and intestinal adaptation and may be predictive of PN dependence. Small intestinal enterocytes are unique in their ability to synthesize and export citrulline to the blood. Fasting plasma citrulline levels correlate with residual small-bowel length in patients with SBS [23]. In addition, higher levels of citrulline (>15 μmol/L) may be predictive of achieving independence from PN [24].

Other complications associated with intestinal failure

Gastric hypersecretion is a problem after major small-bowel resection, as decreased gastrin breakdown leads to hypergastrinemia and potentially gastroduodenal ulceration [25,26]. In addition, increased acid present in the remnant small bowel can decrease the activity of pancreatic enzymes, which function in a narrow pH range. Acid-reducing therapy, either via proton pump inhibition or histamine blockade can help reduce enteral output. For this reason, we empirically manage all patients on a proton pump inhibitor for at least the first 6 months following intestinal loss. We will consider stopping therapy at that point, especially in patients with recurrent line infections, as the acid in the stomach provides a natural barrier to limit bacterial overgrowth.

As part of the adaptive process, the small bowel undergoes dilation. Along with less effective aboral peristalsis and changes in anatomy, increased secretion may promote abnormal growth of bacteria. Normally, the terminal ileum acts as a transition zone between the proximal small bowel, which contains mostly aerobic bacteria, and the colon, which contains mostly gram-negative organisms and anaerobes. These latter bacteria may be beneficial in the colon, where they are capable of fermenting unabsorbed carbohydrates to short-chain fatty acids (most important is likely butyrate) that can promote epithelial barrier function, sodium and chloride absorption, and serve as an important energy source. The negative consequences that occur with bacterial overgrowth include the production of toxic metabolites, translocation of bacteria into the bloodstream, and altered use of luminal nutrients [27]. If this occurs, it may result in prolonged dependence on PN, liver injury, increased rates of CRIs, and malabsorption [28]. The very high rate of recurrent bloodstream infections in infants with SBS is at least in some part a result of gut barrier dysfunction and impaired immunity, both in the gut and systemically. Translocation of indigenous intestinal microbes has been shown to occur in animal models of SBS, with the translocation being promoted by generalized host immunosuppression, gut-associated immune dysfunction, bacterial overgrowth, and gut barrier dysfunction [28,30].

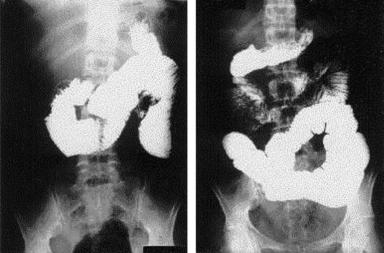

Correctly diagnosing this condition is difficult, as an invasive endoscopic procedure is required to obtain luminal samples (gold standard) and breath hydrogen tests may not be reliable in patients with SBS; therefore, the diagnosis is often made empirically [31]. Contrast studies may demonstrate diffuse dilation in the absence of obstruction (Fig. 1). Many of the signs and symptoms of bacterial overgrowth are indistinguishable from symptoms of intestinal failure: feeding intolerance, diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, unexplained acidosis, and poor weight gain. As a result, the use of antibiotic regimens to decrease bacterial content and shift the balance to luminal flora less detrimental to the patient is an important adjunct. To hinder the production of resistant species, a rotational antibiotic regimen with on and off weeks is recommended. Probiotics may be useful in both the prevention and treatment of bacterial overgrowth. These are live organisms that may provide a benefit by populating the gut with nonpathogenic bacteria. Unfortunately, there are no strong data supporting their use at this time. The use of probiotics during periods of antibiotic regimens to treat bacterial overgrowth is counterproductive and is not recommended.

Fig. 1 Upper part of gastrointestinal tract demonstrating small intestinal dilation consistent with intestinal failure. Note the diffuse dilation in the absence of obstruction.

With impaired carbohydrate absorption, bacterial fermentation in the bowel lumen may also result in the production of D-lactate. In these patients, malabsorbed carbohydrate is fermented by an abnormal bacterial flora in the colon that produces D-lactate, thus resulting in D-lactic acidosis. This anion gap acidosis can result in neurologic symptoms, including altered mental status, slurred speech, and ataxia. The diagnosis is made by the presence of elevated D-lactate in the blood or urine. D-lactic acidosis is managed by reduction or elimination of carbohydrates and administering sodium bicarbonate along with antibiotics. As there have been no adequate clinical trials of antibiotics or probiotics in children with SBS and bacterial overgrowth, there is currently no approved therapy. However, many antibiotic regimens have proved to be effective in managing this condition when delivered at 1-week to 2-week intervals, with rotation of antibiotic regimens to avoid resistance. Metronidazole (20 mg/kg/d) has achieved the widest popularity; additional options are trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (40–50 mg/kg/d), aminoglycosides given orally, or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Recently, rifaximin has been shown to be effective in adults and has proven to be useful in some of our resistant pediatric patients [32]. When these conditions fail, surgical management of the dilated intestine has been shown to eliminate recurrent episodes in children with SBS.

In addition to complications intrinsic to the intestinal tract, the frequent requirement for central venous access to provide PN leads to CRIs. The incidence of CRI is also significantly higher in children with SBS than in those without SBS (7.8 vs 1.3 per 1000 catheter days) and enteric organisms are responsible for 62% of catheter sepsis in patients with SBS compared with only 12% in patients without SBS [33]. Successful prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CRIs are paramount for any child requiring PN. Cuffed, tunneled central venous catheters (CVCs) are preferable to peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines), as they are less likely to become infected, dislodged, or migrate from a central location. The Infectious Disease Society of America provides guidelines for obtaining blood cultures to diagnose CRI, as well as strategies for catheter salvage [34]. As peripheral blood cultures are frequently difficult to obtain from children, a criteria-based diagnosis of CRI is often not possible. Maintenance of sterile technique during catheter placement is essential.

Both antibiotic and 70% ethanol locks have been used to prevent and treat CRI in children [35,37]. Both have demonstrated some efficacy, specifically by attacking biofilms that are frequently the proximate cause of CRI, but concerns exist with both modalities. Antibiotic locks can promote proliferation of resistant species and require heparin to maintain patency. Ethanol locks can degrade polyurethane CVCs, although no instances of degradation have been reported with silicone catheters. Additional complications of ethanol intoxication, dizziness, nausea, and dyspnea have been reported, although using a dwell time of 4 hours, 3 times per week with withdrawal of the instilled ethanol before flushing resulted in no reports of adverse events. Ethanol should not be used in patients receiving metronidazole, as it can cause a disulfiramlike reaction. Various reports of ethanol lock use in children demonstrate good reductions in CRI rates and decreased need for catheter removal [34,36].

New concepts in medical and surgical management

The use of growth hormones and specific nutrients known to stimulate bowel growth have had limited effectiveness clinically. Challenges to their clinical utility include reversal of the adaptive process after termination of hormonal treatment and a lack of overall intestinal muscle growth (effects are limited to the mucosa) [38–43]. Recently, encouraging data from a randomized, placebo-controlled study of teduglutide (glucagon-like peptide-2 analog) administered for 24 weeks to adult patients with chronic intestinal failure demonstrated a decrease in stoma output associated with a decrease in PN requirements [44]. Of note, 3 patients were completely weaned off PN in this study. Based on the observation in the phase 2 trial that the effects of teduglutide are reversible suggests that chronic long-term treatment will be necessary to sustain this observation [45]. Clinical studies evaluating the early administration of GLP-2 and the effect in pediatric patients are needed. Data from murine intestinal resection models suggest that enhanced and sustained expansion of intestinal stem cells may occur with early administration that do not occur at later time points [46].

Glutamine is a nonessential amino acid that is a primary energy source for the enterocyte. It has been shown in animals and adults to prevent mucosal atrophy and deterioration in gut permeability in patients receiving peripheral nutrition. Glutamine administration improves the growth and function of human gut epithelial cells. When supplemented with Glycyl-Gln, PN-dependent individuals demonstrated significantly increased duodenal villus height and decreased intestinal permeability compared with individuals with standard nonsupplemented compositions. In adults, using a combination of enteral glutamine (30 g/d), subcutaneously administered human growth hormone, and a high-fiber (apple pectin), low-fat diet (20% fat, 20% protein, and 60% carbohydrate) led to improvement of intestinal absorptive capacity and weaning or reducing TPN [47]. The data in children are inconclusive at this time regarding the use of enteral glutamine.

Intestinal dilation is associated with intestinal failure [48]. The past 20 years have seen advances in surgical treatment of these patients after maximization of medical therapy. This group of procedures, most appropriately referred to as autologous intestinal reconstruction surgery (AIRS), gives children who have maximized their medical management another option to achieve intestinal autonomy. It is important to note that surgical management of SBS should not be first-line therapy, but rather an adjunct to diligent management of the remaining functional intestinal mucosa. Two major problems intrinsic to the bowel itself are directly affected by AIRS: dysmotility and bacterial stasis and overgrowth secondary to dilation. The most widely used AIRS procedures are the serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) and longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (LILT). Despite these advances, up to 45% of patients will have complications and/or no clinical improvement following autologous reconstruction of the bowel [49,51].

Bianchi [52] originally reported the longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring procedure in 1980. This operation bluntly divides the mesentery of the bowel into 2 leaflets, each with its own blood supply sufficient to support one-half of the intestinal diameter with blood flow. Once the mesentery has been partitioned, the intestine is divided and then the ends are anastomosed in an isoperistaltic fashion, in effect doubling the length of the intestine. In 2006, a worldwide review of studies involving LILT was published with mixed results in overall survival and weaning from PN [53]. Reported complications beyond those already associated with SBS include anastomotic strictures and bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions, among others.

The serial transverse enteroplasty was initially described in 2003, and the procedure was performed on a human infant that same year [54,55]. STEP uses serial firings of a stapler perpendicular to the long axis of the bowel, alternating from the mesenteric to the antimesenteric side. This results in a zig-zag appearance to the bowel and a luminal diameter of about 2 cm. In addition to SBS, this procedure has been applied in instances of proximal atresias with significant bowel dilation, as well as recurrent episodes of D-lactic acidosis. Patients frequently experience redilation of the bowel after STEP and may require a second procedure. It is important to note that STEP may be used in asymmetrically dilated bowel, unlike the LILT procedure. A 2007 review found no significant difference in complications between the 2 procedures [56].

The concept of “intestinal lengthening” to improve total absorption and function is likely a simplistic view of these procedures. The term autologous reconstruction highlights that what is being accomplished during this surgical procedure is correction of intestinal dysmotility owing to bowel dilation in a manner that maximizes preservation of mucosal surface area. Careful consideration and timing of these procedures is complex and best performed in a center experienced with the care of patients with intestinal failure. In our opinion, elective autologous reconstruction should be delayed until at least 1 year after the initial insult to allow maximal time for adaptation of the remnant bowel. Earlier surgical procedures that result in unexpected postoperative complications that do not allow feeding, such as anastomotic leak, potentially risk hindering the adaptive process, which cannot be reinitiated once it is disrupted. Consideration to perform autologous reconstruction in addition to other procedures, such as resection of a stricture with associated bowel dilation may be beneficial in the correct circumstances. In general, this would be in a patient with minimal remaining dilated bowel and where clinical advancement of enteral nutrition has plateaued. For patients who exhaust all medical and surgical options, intestinal transplantation has been performed with improved results over the past decade with 75% graft and 80% patient survival at 1 year in 2005 [57].

Summary

In conclusion, the management approach to children with intestinal failure is complex. It requires diligent management of nutrition with maximal effort given to achieving as much as possible via the enteral route, involving enteral tubes if necessary. Optimization of enteral feeding should be in a manner that minimizes starting and stopping feeds frequently. In these challenging patients, timely management and preferably prevention of complications can result in significant clinical benefit. Problems such as gastric hypersecretion, bacterial overgrowth, IFALD, and CRIs are unfortunately common in these challenging patients. Autologous intestinal reconstruction should be considered only after adequate time for physiologic adaptation has occurred. With intestinal failure, even small clinical gains can be profound both financially and emotionally for the patients and their families. Strong consideration should be given to early referral to a specialized center with experience in treating the full spectrum of patients with intestinal failure.

References

[1] J.P. Baxter, P.M. Fayers, A.W. McKinlay. A review of the quality of life of adult patients treated with long-term parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2006;25(4):543-553.

[2] C.R. Cole, N.I. Hansen, R.D. Higgins, et al. Very low birth weight preterm infants with surgical short bowel syndrome: incidence, morbidity and mortality, and growth outcomes at 18 to 22 months. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e573-e582.

[3] I.R. Diamond, N. de Silva, P.B. Pencharz, et al. Neonatal short bowel syndrome outcomes after the establishment of the first Canadian multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation program: preliminary experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(5):806-811.

[4] B.P. Modi, M. Langer, Y.A. Ching, et al. Improved survival in a multidisciplinary short bowel syndrome program. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):20-24.

[5] A.U. Spencer, A. Neaga, B. West, et al. Pediatric short bowel syndrome: redefining predictors of success. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):403-409. [discussion: 409–12]

[6] D. Sudan, J. DiBaise, C. Torres, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of intestinal failure. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(2):165-176. [discussion: 176–7]

[7] P.J. Javid, F.R. Malone, J. Reyes, et al. The experience of a regional pediatric intestinal failure program: successful outcomes from intestinal rehabilitation. Am J Surg. 2010;199(5):676-679.

[8] M.C. Struijs, I.R. Diamond, N. de Silva, et al. Establishing norms for intestinal length in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(5):933-938.

[9] P.S. Goday. Short bowel syndrome: how short is too short? Clin Perinatol. 2009;36(1):101-110.

[10] J.J. Estrada, M. Petrosyan, C.J. Hunter, et al. Preservation of extracorporeal tissue in closing gastroschisis augments intestinal length. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(12):2213-2215.

[11] O. Ron, M. Davenport, S. Patel, et al. Outcomes of the “clip and drop” technique for multifocal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(4):749-754.

[12] D.J. Andorsky, D.P. Lund, C.W. Lillehei, et al. Nutritional and other postoperative management of neonates with short bowel syndrome correlates with clinical outcomes. J Pediatr. 2001;139(1):27-33.

[13] I.R. Diamond, A. Sterescu, P.B. Pencharz, et al. The rationale for the use of parenteral omega-3 lipids in children with short bowel syndrome and liver disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(7):773-778.

[14] O. Goulet, F. Ruemmele, F. Lacaille, et al. Irreversible intestinal failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38(3):250-269.

[15] B.A. Carter, R.J. Shulman. Mechanisms of disease: update on the molecular etiology and fundamentals of parenteral nutrition associated cholestasis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4(5):277-287.

[16] R.A. Cowles, K.A. Ventura, M. Martinez, et al. Reversal of intestinal failure-associated liver disease in infants and children on parenteral nutrition: experience with 93 patients at a referral center for intestinal rehabilitation. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(1):84-87. [discussion: 87–8]

[17] D.A. Kelly. Intestinal failure-associated liver disease: what do we know today? Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 Suppl 1):S70-S77.

[18] J.S. Soden. Clinical assessment of the child with intestinal failure. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19(1):10-19.

[19] A. Nasr, Y. Avitzur, V.L. Ng, et al. The use of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia greater than 100 micromol/L as an indicator of irreversible liver disease in infants with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(2):359-362.

[20] T.R. Weber, M.S. Keller. Adverse effects of liver dysfunction and portal hypertension on intestinal adaptation in short bowel syndrome in children. Am J Surg. 2002;184(6):582-586. [discussion: 586]

[21] P.W. Wales, E.R. Christison-Lagay. Short bowel syndrome: epidemiology and etiology. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19(1):3-9.

[22] C. Bailly-Botuha, V. Colomb, E. Thioulouse, et al. Plasma citrulline concentration reflects enterocyte mass in children with short bowel syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(5):559-563.

[23] P. Crenn, C. Coudray-Lucas, F. Thuillier, et al. Postabsorptive plasma citrulline concentration is a marker of absorptive enterocyte mass and intestinal failure in humans. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1496-1505.

[24] S. Fitzgibbons, Y.A. Ching, C. Valim, et al. Relationship between serum citrulline levels and progression to parenteral nutrition independence in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(5):928-932.

[25] P.E. Hyman, S.L. Everett, T. Harada. Gastric acid hypersecretion in short bowel syndrome in infants: association with extent of resection and enteral feeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5(2):191-197.

[26] P.E. Hyman, T.Q. Garvey3rd, T. Harada. Effect of ranitidine on gastric acid hypersecretion in an infant with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4(2):316-319.

[27] C.R. Cole, T.R. Ziegler. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth: a negative factor in gut adaptation in pediatric SBS. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9(6):456-462.

[28] C.R. Cole, J.C. Frem, B. Schmotzer, et al. The rate of bloodstream infection is high in infants with short bowel syndrome: relationship with small bowel bacterial overgrowth, enteral feeding, and inflammatory and immune responses. J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):941-947. 947.e941

[29] P. Aldazabal, I. Eizaguirre, M.J. Barrena, et al. Bacterial translocation and T-lymphocyte populations in experimental short-bowel syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8(4):247-250.

[30] G. Schimpl, G. Feierl, K. Linni, et al. Bacterial translocation in short-bowel syndrome in rats. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9(4):224-227.

[31] G.R. Corazza, M.G. Menozzi, A. Strocchi, et al. The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Reliability of jejunal culture and inadequacy of breath hydrogen testing. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(2):302-309.

[32] M. Majewski, S.C. Reddymasu, S. Sostarich, et al. Efficacy of rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, in the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(5):266-270.

[33] A.G. Kurkchubasche, S.D. Smith, M.I. Rowe. Catheter sepsis in short-bowel syndrome. Arch Surg. 1992;127(1):21-24. [discussion: 24–5]

[34] L.A. Mermel, M. Allon, E. Bouza, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1-45.

[35] B.A. Jones, M.A. Hull, D.S. Richardson, et al. Efficacy of ethanol locks in reducing central venous catheter infections in pediatric patients with intestinal failure. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(6):1287-1293.

[36] E. Mouw, K. Chessman, A. Lesher, et al. Use of an ethanol lock to prevent catheter-related infections in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(6):1025-1029.

[37] P. Toltzis. Antibiotic lock technique to reduce central venous catheter-related bacteremia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(5):449-450.

[38] P.L. Brubaker, A. Crivici, A. Izzo, et al. Circulating and tissue forms of the intestinal growth factor, glucagon-like peptide-2. Endocrinology. 1997;138(11):4837-4843.

[39] M.A. Helmrath, C.E. Shin, C.R. Erwin, et al. The EGF\EGF-receptor axis modulates enterocyte apoptosis during intestinal adaptation. J Surg Res. 1998;77(1):17-22.

[40] P.B. Jeppesen, J. Szkudlarek, C.E. Hoy, et al. Effect of high-dose growth hormone and glutamine on body composition, urine creatinine excretion, fatty acid absorption, and essential fatty acids status in short bowel patients: a randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(1):48-54.

[41] J.S. Scolapio. Effect of growth hormone and glutamine on the short bowel: five years later. Gut. 2000;47(2):164.

[42] A. Tavakkolizadeh, R. Shen, J. Jasleen, et al. Effect of growth hormone on intestinal Na+/glucose cotransporter activity. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001;25(1):18-22.

[43] H. Yang, B.E. Wildhaber, D.H. Teitelbaum. 2003 Harry M. Vars Research Award. Keratinocyte growth factor improves epithelial function after massive small bowel resection. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27(3):198-206. [discussion: 206–7]

[44] P.B. Jeppesen, R. Gilroy, M. Pertkiewicz, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of teduglutide in reducing parenteral nutrition and/or intravenous fluid requirements in patients with short bowel syndrome. Gut. 2011. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1136/gut.2010.218271.

[45] P.B. Jeppesen, E.L. Sanguinetti, A. Buchman, et al. Teduglutide (ALX-0600), a dipeptidyl peptidase IV resistant glucagon-like peptide 2 analogue, improves intestinal function in short bowel syndrome patients. Gut. 2005;54(9):1224-1231.

[46] A.P. Garrison, C.M. Dekaney, D.C. von Allmen, et al. Early but not late administration of glucagon-like peptide-2 following ileo-cecal resection augments putative intestinal stem cell expansion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296(3):G643-G650.

[47] T.A. Byrne, T.B. Morrissey, T.V. Nattakom, et al. Growth hormone, glutamine, and a modified diet enhance nutrient absorption in patients with severe short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1995;19(4):296-302.

[48] D.W. Wilmore, M.K. Robinson. Short bowel syndrome. World J Surg. 2000;24(12):1486-1492.

[49] A. Bianchi. Longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring: results in 20 children. J R Soc Med. 1997;90(8):429-432.

[50] J. Bueno, J. Guiterrez, G.V. Mazariegos, et al. Analysis of patients with longitudinal intestinal lengthening procedure referred for intestinal transplantation. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(1):178-183.

[51] E.A. Miyasaka, P.I. Brown, D.H. Teitelbaum. Redilation of bowel after intestinal lengthening procedures—an indicator for poor outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(1):145-149.

[52] A. Bianchi. Intestinal loop lengthening—a technique for increasing small intestinal length. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15(2):145-151.

[53] A. Bianchi. From the cradle to enteral autonomy: the role of autologous gastrointestinal reconstruction. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2 Suppl 1):S138-S146.

[54] H.B. Kim, D. Fauza, J. Garza, et al. Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP): a novel bowel lengthening procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(3):425-429.

[55] H.B. Kim, P.W. Lee, J. Garza, et al. Serial transverse enteroplasty for short bowel syndrome: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(6):881-885.

[56] D. Sudan, J. Thompson, J. Botha, et al. Comparison of intestinal lengthening procedures for patients with short bowel syndrome. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):593-601. [discussion: 601–4]

[57] T.M. Fishbein. Intestinal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):998-1008.