22 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Clinical Presentation

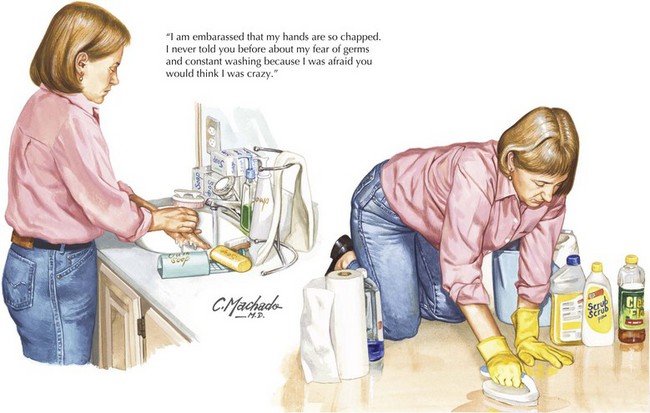

OCD patients usually fit into one of a few categories. Some clean obsessively and worry about germs or contamination (Fig. 22-1). Others repeatedly check that they’ve turned off their appliances or locked their doors. Some are obsessed with symmetry or arranging their possessions in exactly the right order. Another group hoards what most would call “junk.” Often, OCD patients are troubled by thoughts of violence; they may fear that they will run someone over while driving or that as they eat a knife will slip from their hands and cut someone. Inexperienced clinicians sometimes err by seeing these obsessions as real threats, thereby exacerbating patients’ fears. In fact, OCD patients are terrified of these thoughts and do not act on them.

An SK, Mataix-Cols D, Lawrence NS, et al. To discard or not to discard: the neural basis of hoarding symptoms in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 Jan 8.

Burdick A, Goodman WK, Foote KD. Deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Front Biosci. 2009 Jan 1;14:1880-1890.

Clark DA. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for OCD. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004.

Olley A, Malhi G, Sachdev P. Memory and executive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a selective review. J Affect Disord. 2007 Dec;104(1-3):15-23.

Rapoport JL. The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Washing: The Experience and Treatment of Obsessive compulsive disorder. New York, NY: Signet; 1997.

Swedo SE, Swedo SE, Leonard HL, et al. Pediatric Autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am J Psych. 1998;155:264-271.