chapter 37 Obesity

BACKGROUND

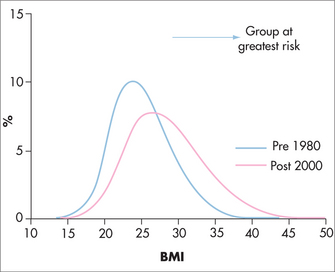

Increased prevalence of obesity is an issue confounding health policy makers across the developed and developing world (Fig 37.1). In medicine, disciplines that have not had to deal with obesity-related illness are having to change management practices to counter it, and the role of cigarette smoking as our leading preventable cause of illness is rapidly being supplanted by overweight. Population surveys in Australia and internationally, while varying depending on the populations studied,1,2 show that starting from the paediatric age group, the prevalence of obesity increases in all age groups up to about the sixth decade.

In the United States in 2007–2008, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 33.8% overall, 32.2% among men and 35.5% among women. The corresponding prevalence estimates for overweight and obesity combined (BMI ≥ 25) were 68.0%, 72.3% and 64.1%.4 A review of prevalence estimates in European countries found that the prevalence of obesity based on measured weights and heights varies widely from country to country, with higher prevalences in central, eastern and southern Europe.5

The Ausdiab Study showed a prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australia of over 50%.6 Data for children and adolescents are incomplete but from a demographic point of view at least, the progression from normal weight to overweight and obesity seems to be progressive rather than reversible, so that patients who develop weight problems are more likely to develop further weight problems than undergo substantial improvement. A significant percentage of obese adolescents will be expected to become obese adults.7

According to the UK Counterweight Trial, obese patients are more frequent presenters to general practitioner (GP) clinics8 and more likely to be actively treated with medications9,10 than the average patient, so the population prevalence of obesity will usually under-represent the number of obese patients that a practitioner will actually see. Normalisation of obesity in the community allows it to be chronically under-recognised, and many patients who could benefit from intervention by a GP will miss out if active screening and action are not part of practice policy.11,12 Table 37.1 shows BMI and waist circumference values for the Caucasian population. Risk stratification by BMI for non-Caucasian populations is more difficult, and because they may be at risk of adverse metabolic problems at a lower weight, any evidence of excess abdominal adiposity may warrant formal assessment for the metabolic syndrome (Box 37.1). Estimation of childhood and adolescent weight disorders relies on using growth charts created by the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with patients classified as overweight when above the 85th percentile, and obese when above the 95th percentile.

TABLE 37.1 Classification of obesity and overweight in Caucasians13

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) | Waist circumference (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal range | 18.5–24.9 | |

| Overweight | 25–29.9 | > 94 (male) > 80 (female) |

| Obese | > 30 | > 102 (male) > 88 (female) |

| Class I | 30–34.9 | |

| Class II | 35–39.9 | |

| Class III | > 40 |

BOX 37.1 Diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome14,15

2005 International Diabetes Federation definition of the metabolic syndrome:

WHAT CAUSES OBESITY?

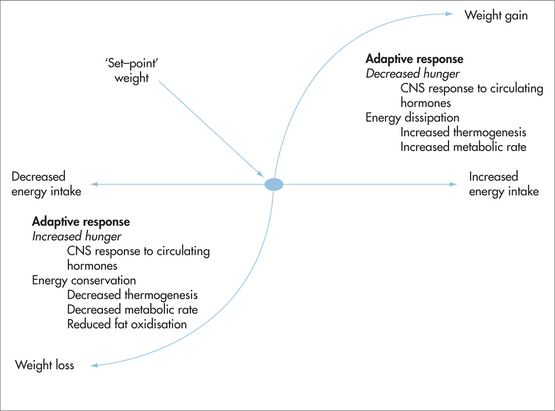

While the underlying force driving weight gain in an individual is chronic energy imbalance, the seeming simplicity of weight maintenance hides multiple layers of complexity that relate as much to genetic and environmental factors16–19 as to voluntary food and exercise choices. Evolution has given us physiological systems that work to maintain ‘current weight’ without voluntary control and offer significant resistance to weight change (Fig 37.2). In both overfeeding and underfeeding studies there is resistance to changes in body composition, so that diets of energy surplus or restriction, while changing weight in the short term, will usually have little long-term effect on weight. Long-term positive energy imbalance gradually wears down the relatively weak metabolic defences against weight gain and this leads to creation of extra fat stores. These extra stores are rigorously defended when they are threatened by attempts at voluntary weight loss (Box 37.2), and thus chronic weight gain is encouraged and weight loss seemingly unobtainable. Environmental changes leading to increasing availability of energy-dense food, combined with a decline in opportunities to expend calories in everyday activities, have disengaged the ‘brakes’ that have previously allowed most people to remain weight stable.20 Failing societal cues for eating and exercise are yet to be replaced by effective public health policy, and lessons learned from successful public health campaigns relying on legislative changes to bolster education (i.e. tobacco smoking) have yet to be applied in obesity prevention. Studies looking at preventing weight gain in ‘at-risk’ populations are plagued by compliance and methodological problems, but patients who are frequent users of healthcare, such as pregnant women21 and patients with depressive illness,22 can benefit from weight management programs, and therefore these patients and others who are regular attendees at GP clinics are ideal candidates for intervention.

FIGURE 37.2 (and Box 37.2) The relationship between energy intake and weight is not linear.17,23–26 Most people’s weight varies within a 3–5 kg range, and once they leave this range a number of mechanisms are triggered,27,28 which return that person to their previous range, or, if the energy changes are long-lasting, act to reduce weight change by either increasing (energy excess) or decreasing (energy deficit) metabolic rate29–32 and altering hunger signals33,34 to help return the individual to their earlier range.35 Weight loss triggers a complex array of metabolic and behavioural changes. Patients losing weight often find that they manage early weight loss without great difficulty, then reach a plateau beyond which they cannot go without great effort. They become progressively psychologically distressed the longer the diet persists,36 and when they cease dieting they recover their lost kilos at a rapid rate, often overshooting their start weight.37

BOX 37.2 Measured physiological responses to weight loss

OBESITY-RELATED ILLNESS

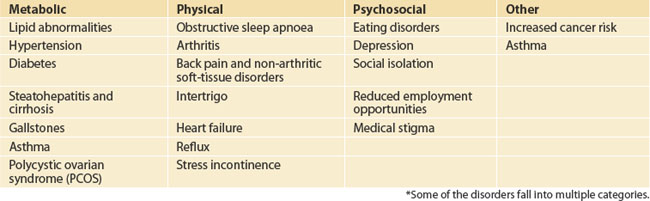

Weight-related comorbidities are often a mixture of both metabolic and ‘mass-related’ physical changes (Table 37.2). An overweight patient’s expanded adipocyte mass functions as an active endocrine organ, with production of endocrine and paracrine substances as well as cytokines, which affect the systemic and portal circulations, leading to the metabolic effects of insulin resistance, including lipid and glucose abnormalities, reproductive hormone changes and hypertension. The physical manifestations of obesity, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux, sleep apnoea and arthritis, probably have metabolic associations also, but these are not well understood, and although obesity is significantly associated with cancers of the uterus, breast, colon and oesophagus, the mechanisms behind this are also not well understood.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

DEFINING GOALS

Despite the diversity in patients needing weight management, and regardless of the resources available to the GP and the patient, the goals need to be health based. Some patients will be seeking weight loss, some will be undergoing treatment for metabolic or physical conditions, and some will be unaware of, or resistant to, linking their weight with their health. When devising a weight control strategy, weight loss itself needs to be viewed as the least effective measure of success and is the least likely outcome. Obtaining and maintaining a reduced-calorie diet combined with any degree of exercise will prevent weight gain, help control cholesterol and blood pressure problems, reduce abdominal girth, prevent progression of impaired glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes, and potentially reduce mortality risk.38 Discussing weight issues in terms of health will significantly reduce the risk that the patient will treat your advice in the same manner that they treat the varied, conflicting and erroneous advice they receive from various forms of the dieting ‘industry’. Most diet-induced weight loss is invariably followed by weight regain, as the dietary process creates an artificial and unsustainable approach to food and exercise, rather than teaching the skills necessary to manage weight and maintain health in the long term.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

A range of weight management tools is available to the GP and can be used depending on the circumstances of the patient. Some obesity treatments may not be freely available, but most of those used in hospital-based obesity clinics are available in the community (Box 37.3). Guiding patients towards healthy eating habits and sustainable exercise patterns is the ultimate goal, but there will be times when weight loss itself is viewed as important, and if this is the case it is useful to know the nature and effects of obesity therapies. While occasional patients will have dramatic results from non-lifestyle treatments, it is unusual for these to persist, and weight regain usually leaves the patient in worse mental and physical health.

BOX 37.3 Nature and effects of readily available obesity treatments13,39–45

Reduced-energy diet

Very-low-energy diet

Exercise therapy

Successful weight loss

Box 37.4 shows data obtained from groups of patients who have not only lost weight, but kept it off in the long term. The medical data are primarily from the National Weight Control Registry,61 which is an observational study of patients who have maintained > 13.6 kg of weight loss for more than 12 months, and is the largest non-surgical weight-loss cohort in the world. Regardless of the route taken to weight loss, the destination is the same. Patients who lose large amounts of weight consume a diet that is significantly reduced in calories, food choice and spontaneity. They undertake about an hour of aerobic exercise a day, and if they ever regain weight they struggle to lose it again. As patients with weight problems are used to eating more and exercising less than their weight-normal peers, it is no surprise that so few can manage the self-imposed deprivation that this entails.

BOX 37.4 Attributes of successful weight-loss patients

In both surgical and non-surgical groups, the key to success is prolonged caloric restriction.62–74

Dietary weight loss

Surgical weight loss

Water

Some patients sense hunger when they are thirsty. Increasing water consumption before a meal may help reduce hunger.46

Psyllium

Soluble fibre such as psyllium may help lower insulin levels,47 reduce hunger,48 delay gastric emptying and increase the subjective sensation of satiety.

Citrus aurantium

Citrus aurantium is a popular ingredient in weight-loss products, substituting for the banned ephedra in the United States. The main ingredient, synephrine, produces effects on human metabolism that could be useful for reducing fat mass in obese humans because it stimulates lipolysis and raises metabolic rate and fat oxidation through increased thermogenesis.50 Two small clinical studies suggest possible weight reduction.51 More research is needed.

Mind–body issues and weight management

For a range of reasons, no integrated approach to weight management should ignore the role of the mind. First, it is well documented that stress and psychological factors often compound poor eating patterns, leading to under- or over-nutrition. Food is often used as compensation for emotional disturbances. Secondly, the mind’s effect on allostasis contributes to the development of metabolic syndrome. Thirdly, mind–body therapies have an important role to play in the management of this condition as well as in reducing cardiovascular risk.52 A range of psychological and mind–body therapies have been trialled with success for weight management and eating disorders.53 These include mindfulness-based therapies54,55 and hypnosis,56 although any psychological strategy that is effective in improving mental health or stress management could also be helpful in weight management. Cognitive behaviour therapy is effective for children, adolescents57 and adults.58 Behaviour change strategies also play an important adjunctive role.

It is important to be reminded that the role of psychological therapies is not only to aim for weight loss but also to help improve the quality of a person’s life, regardless of their weight. A healthier psychological approach to eating should be seen as a mandatory part of sustainable and healthy weight loss. Dr Rick Kausman’s program on weight management is a good example of such an approach that is easy to implement in the primary care setting.59,60 The following are some of the key points in this program.

CLINICAL SCENARIOS

RAPID WEIGHT GAIN

Most GPs will be familiar with the tendency of some high-risk individuals to gain weight rapidly as a result of lifestyle change or illness. As these weight changes are likely to become permanent unless tackled early, a ‘rescue’ plan to identify and treat vulnerable patients is worth considering. Patients in the postpartum period, especially if suffering from depression or with a history of weight problems, are a clear example of this, as are patients undergoing treatment for severe depression, or after suffering an injury or disabling musculoskeletal complaint, hysterectomy or diagnosis of an endocrine disorder such as PCOS, thyroid problem or diabetes. Many patients may miss the opportunity to start a weight management plan because of the focus on their mental or physical disorder. Setting aside time to discuss weight management during a separate consultation will be required in many cases, and for patients with depression,22,75–78 and probably also those in the postpartum period, an exercise program, even if unsustainable in the long term, may be enough to offer significant help.

The diagnosis of diabetes can be followed by weight gain, with some medications, especially insulin, contributing to this.79 In this group also, regular exercise is important as a way of increasing insulin sensitivity as well as increasing energy expenditure.

| Drug | Action | Weight loss > placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Phentermine, diethylproprion |

PATIENTS WITH SIGNIFICANT OBESITY AND OBESITY-RELATED DISEASE

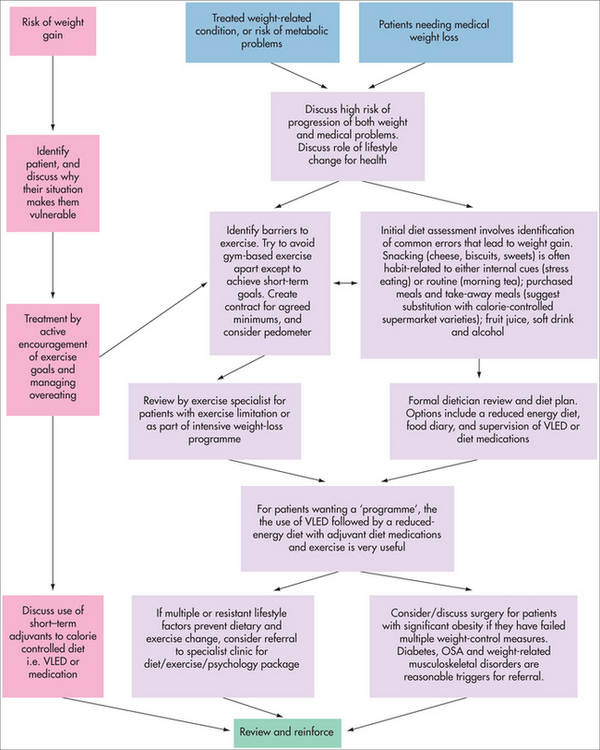

This group of patients is the smallest in number but the most difficult to deal with, and will often consume time and resources without any obvious gains being made. The GP’s role in caring for this group is again directed towards achieving health goals that can be maintained. Focusing on weight loss as a primary measure of the success of your relationship with these patients is more likely to lead to detachment of the patient from your practice than actually achieving weight loss. Successful weight management can only come as a result of sustainable healthy eating and exercise habits, but these patients will often require significant rehabilitation of their lifestyle to achieve this.80 Delegation of some of these tasks to a trusted dietician and an exercise physiologist is important, but these support staff need to be briefed to provide a plan that will not over-stretch the patient and lead to non-compliance. A suggested algorithm for GP-based weight management is given in Fig 37.3, but some of the easiest methods, combining a very-low-energy diet with dietician and exercise program, preferably avoiding pharmacotherapy as ‘standalone’ treatment,81 are also some of the most effective,39,82 and these can be recommended as a core management tool that most practices will be able to access.

Exercise for patients with significant obesity and obesity-related disease

Most patients with significant obesity will be unable to manage the enthusiastic exercise challenges recommended by gyms, but will still need to include exercise in their routine. Significantly obese individuals find it difficult to engage in strenuous, and sometimes almost any, exercise. Regular aerobic exercise is difficult to sustain for obese individuals, and its effects on weight loss have been overstated.62,83–88 The benefits of regular exercise on health, however, cannot be emphasised enough, and it is also useful in reducing the risk of further weight gain.89 Enlisting the help of an exercise physiologist, or someone with similar interests, is worthwhile in formulating an exercise plan for these patients, as many have physical limitations that make regular exercise difficult. Setting goals for exercise should include goals for incidental exercise such as walking at home and at work, and while using a pedometer is a useful approach to aid this, the aim should be to achieve and sustain minimum rather than ‘ideal’ targets.

There will be occasions when patients need referral to specialist weight management clinics, or referral for consideration of surgery. One advantage that hospital-based weight management clinics or multidisciplinary integrative clinics may have over general practice is the ready access to experienced support staff with special interest in obese patients, and this makes them ideally placed when caring for patients who can be resource intensive when attempting to correct their substantial lifestyle barriers to weight control. Patients referred to hospital-based clinics will continue to attend their general practice for ongoing care, and when this occurs it is very useful to encourage contact between your own support staff and those in the clinic. Specialist dieticians and exercise physiologists are usually passionate about their work and are an excellent and often under-utilised resource for community practitioners. There is little in the way of published data on weight-loss outcomes from such referrals, but while greater than single-digit (in kilograms) weight loss is unlikely,90,91 the focused treatment of medical and lifestyle problems will usually justify the intervention.

Psychology referral for patients with significant obesity

Whether to include a psychologist in the care of these patients is a complex issue. While the rate of eating disorders is high in the significantly obese,92,93 obesity itself is a condition of disordered physiology, and therefore eating disorders are more likely to be a result than a cause of their obesity. Referral to a psychologist with a special interest in weight problems is unlikely to cause weight loss in itself, but it can assist in future weight management if patients are receptive to considering changing their relationship to food and lifestyle. Suggesting referral to a psychologist takes some tact, and needs to be done when the patient is able to understand the reasoning behind the referral.

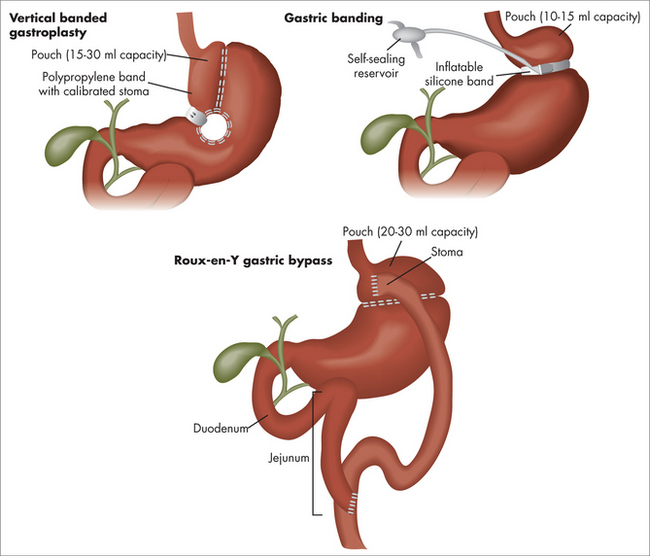

Surgical intervention for significant obesity

Most GPs will see significantly obese patients who require or seek long-term weight loss. When this is the case it is reasonable to discuss surgical intervention, but obviously there are access and equity issues that will make this impractical for many.94 In all published comparisons of surgical versus medical treatments for obesity, the magnitude of weight loss achieved and maintained by surgery is 5–10 times greater than any and all medical treatments.40–42,95 Although the idea of weight-loss surgery appears strange at first glance, it is rapidly being embraced by patients in Australia and overseas. Several types of procedures are available (Fig 37.4), but most work by encouraging patients to embrace low-calorie eating and increased physical activity. These operations significantly reduce hunger and the speed at which patients can eat, and this leads to weight loss through reduced calorie intake. If patients desire to overeat or eat high-calorie foods, they will manage to do this but will not lose weight, and so an important part of preoperative selection of patients is choosing those who wish to change their lifestyle but have been unable to do so (Fig 37.3). The risks of surgery are similar in magnitude to those of laparoscopic cholecystectomy or joint replacement, and while Australia has some of the best results in the world, a lot of this is attributed to the follow-up team, and patients who are unable or unwilling to come to regular review usually fail to embrace the lifestyle changes required and will not lose weight. Obvious candidates for surgical intervention are those with type 2 diabetes (of whom 40–80% can be expected to cease diabetes treatments44), severe sleep apnoea and mobility problems who have failed well-supported conservative weight loss efforts.

THE OVERWEIGHT CHILD

Management of weight problems in the young is hampered by under-recognition and by the resistance that many feel about giving and receiving advice on parenting issues, but these barriers should not be allowed to deter clinicians from dealing with what can become a serious and intractable condition.96 Liberal use of growth charts during routine assessment of children will help de-stigmatise discussions and improve early pick-up, but determining when and how to intervene can be very difficult. There is increasing awareness that childhood obesity increases illness risk, significantly reduces self-esteem97,98 and quality of life, and usually progresses into adult obesity.

As children have limited ability to control their environment, changing the factors that contribute to obesity requires enlisting the parents or guardians of the child to create an environment where excess calorie consumption and sedentary behaviour are discouraged. As overweight children often live with overweight families, they can have a combination of both genetics and environment working against them from a young age, and this needs to be brought into the discussion whenever possible. Overweight parents can be very unhappy about their own weight, and so this can be used as a factor to drive the ‘whole of family’ approach to weight management that will be required. While it is known that watching a lot of television,3 reduced energy expenditure through exercise and disordered parental eating can predispose to weight problems, it is not known whether correcting these problems will reduce weight. Despite the lack of evidence, these factors are potentially the most readily modifiable and so they can form the basis of your interaction with the patient and family. The aim of such an intervention is to promote healthy, reduced-calorie intake and increased exercise, which hopefully will allow the child to decrease their body fat percentage as they grow. Very overweight children may require referral to an accredited practising dietician with a special interest in pediatrics, or to specialist clinics, and as a significant number of eating disorders develop in adolescents, an awareness of the need for psychological help for some patients is also warranted.

CONCLUSION

General practitioners have ‘pole position’ in weight management due to the long-term relationship they have with patients. This relationship can be used to promote the healthy habits that are the core of successful weight management.7 A large number of significant health benefits occur very early in the process of weight loss and are related more to a reduction in calorie excess and avoidance of sedentary behaviour than to any particular change in weight. Picking up on these positives, and pointing out that they occur as a result of health improvement rather than weight loss, can set the tone for further consultations in future. When patients understand the difficulties of weight control, and become comfortable with the idea that diets work through calorie restriction rather than through magical alteration in their body’s functioning, they can view the weight management tools available and use them appropriately to achieve improved long-term health.

National Weight Control Registry. http://www.nwcr.ws/.

NIH Obesity Information. http://health.nih.gov/topic/Obesity.

Zimmet PZ, Alberti KG, Shaw JE. Mainstreaming the metabolic syndrome: a definitive definition. Med J Aust. 2005;183(4):175-176. (this new definition should assist both researchers and clinicians)

1 Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1197-1209.

2 Stewart S, Stewart S, Tikellis G, et al. Australia’s future ‘Fat Bomb’: a report on the long-term consequences of Australia’s expanding waistline on cardiovascular disease. Melbourne, Australia: Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, 2008.

3 Ogden CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, et al. Obesity among adults in the United States—no change since 2003–2004. NCHS data brief no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007.

4 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US Adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235-241.

5 Berghöfer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, et al. Obesity prevalence from a European perspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:200.

6 Cameron AJ, Welborn TA, Zimmet PZ, et al. Overweight and obesity in Australia: the 1999–2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Med J Aust. 2003;178(9):427-432.

7 Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, et al. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(3):653-658.

8 Frost GS, Lyons GF. Obesity impacts on general practice appointments. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1429-1442.

9 Counterweight Project Team. The impact of obesity on drug prescribing in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):743-749.

10 Ross HM, Laws R, Reckless J, et al. Evaluation of the Counterweight Programme for obesity management in primary care: a starting point for continuous improvement. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(553):548-554.

11 Laws R. Current approaches to obesity management in UK primary care: the Counterweight Programme. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2004;17(3):183-190.

12 Tan D, Zwar NA, Dennis SM, et al. Weight management in general practice: what do patients want? Med J Aust. 2006;185(2):73-75.

13 Proietto J, Baur LA. 10: Management of obesity. Med J Aust. 2004;180(9):474-480.

14 Zimmet PZ, Alberti KG, Shaw JE. Mainstreaming the metabolic syndrome: a definitive definition. Med J Aust. 2005;183(4):175-176.

15 Chew GT, Gan SK, Watts GF. Revisiting the metabolic syndrome. Med J Aust. 2006;185(8):445-449.

16 Cornier MA, Grunwald GK, Johnson SL, et al. Effects of short-term overfeeding on hunger, satiety, and energy intake in thin and reduced-obese individuals. Appetite. 2004;43(3):253-259.

17 Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, et al. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006;443(7109):289-295.

18 Wisse BE, Kim F, Schwartz MW. Physiology. An integrative view of obesity. Science. 2007;318(5852):928-929.

19 Chung WK, Leibel RL. Considerations regarding the genetics of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(Suppl 3):S33-S39.

20 Swinburn B, Egger G. The runaway weight gain train: too many accelerators, not enough brakes. BMJ. 2004;329(7468):736-739.

21 Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Beckers K, et al. Maternal obesity: pregnancy complications, gestational weight gain and nutrition. Obes Rev. 2008;9(2):140-150.

22 Blouin M, Tremblay A, Jalbert ME, et al. Adiposity and eating behaviors in patients under second generation antipsychotics. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:1780-1797.

23 Bessard T, Schutz Y, Jéquier E, et al. Energy expenditure and postprandial thermogenesis in obese women before and after weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38(5):680-693.

24 Schutz Y. Macronutrients and energy balance in obesity. Metabolism. 1995;44(9)(Suppl 3):7-11.

25 Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001;104(4):531-543.

26 Schutz Y. Dietary fat, lipogenesis and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2004;83(4):557-564.

27 Weyer C, Pratley RE, Salbe AD, et al. Energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and body weight regulation: a study of metabolic adaptation to long-term weight change. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1087-1094.

28 Doucet E, Cameron J. Appetite control after weight loss: what is the role of bloodborne peptides? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32(3):523-532.

29 Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J, et al. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10):621-628.

30 Ranneries C, Bulow J, Buemann B, et al. Fat metabolism in formerly obese women. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(1 Pt 1):E155-E161.

31 Crescenzo R, Samec S, Antic V, et al. A role for suppressed thermogenesis favoring catch-up fat in the pathophysiology of catch-up growth. Diabetes. 2003;52(5):1090-1097.

32 Major GC, Doucet E, Trayhurn P, et al. Clinical significance of adaptive thermogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31(2):204-212.

33 Doucet E, Imbeault P, St Pierre S, et al. Appetite after weight loss by energy restriction and a low-fat diet-exercise follow-up. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(7):906-914.

34 Drapeau V, King N, Hetherington M, et al. Appetite sensations and satiety quotient: predictors of energy intake and weight loss. Appetite. 2007;48(2):159-166.

35 Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte DJ, et al. Is the energy homeostasis system inherently biased toward weight gain? Diabetes. 2003;52(2):232-238.

36 Chaput JP, Arguin H, Gagnon C, et al. Increase in depression symptoms with weight loss: association with glucose homeostasis and thyroid function. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33(1):86-92.

37 Dulloo AG, Jacquet J, Girardier L, et al. Poststarvation hyperphagia and body fat overshooting in humans: a role for feedback signals from lean and fat tissues. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(3):717-723.

38 Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, et al. Intentional weight loss and death in overweight and obese US adults 35 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):383-389.

39 Egger GJ. Are meal replacements an effective clinical tool for weight loss? A clarification. Med J Aust. 2006;184(11):591.

40 Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, et al. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(5):579-584.

41 Norris SL, Zhang X, Avenelli A, et al. Long-term effectiveness of lifestyle and behavioral weight loss interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2004;117(10):762-774.

42 Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C, et al. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2226-2238.

43 Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Vogt RA, et al. Lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: a pilot investigation of a potential primary care approach. Obes Res. 1997;5(3):218-226.

44 Haddock CK, Poston WS, Foreyt JP, et al. Effectiveness of Medifast supplements combined with obesity pharmacotherapy: a clinical program evaluation. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13(2):95-101.

45 Wadden TA, McGuckin BG, Rothman RA, et al. Lifestyle modification in the management of obesity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(4):452-463.

46 van Walleghen EL, Orr JS, Gentile CL, et al. Under acute test meal conditions, pre-meal water consumption reduces meal energy intake in older but not younger adults. Obesity. 2007;15:93-99.

47 Sierra M, Garcia JJ, Fernandez N, et al. Therapeutic effects of psyllium in type 2 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:830-842.

48 Turnbull WH, Thomas HG. The effect of a Plantago ovata seed containing preparation on appetite variables, nutrient and energy intake. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:338-342.

49 Brala PM, Hagen RL. Effects of sweetness perception and calorie value of a preload on short-term intake. Physiol Behav. 1983;30(1):1-9.

50 Braun L, Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements. An evidence-based guide. 2nd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2007.

51 Preuss HG, DiFerdinando D, Bagchi M, et al. Citrus aurantium as a thermogenic, weight reduction replacement for ephedra: an overview. J Med. 2002;33:247-264.

52 Innes KE, Vincent HK, Taylor AG. Chronic stress and insulin resistance-related indices of cardiovascular disease risk, part 2: a potential role for mind-body therapies. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13(5):44-51.

53 Chrubasik S, Chrubasik C, Torda T. Early impact of a combined dietary and psychological intervention on BMI, blood pressure, and quality of life. Fam Med. 2006;38(3):160.

54 Kristeller J, Hallett C. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:357-363.

55 Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Singh AN, et al. A mindfulness-based health wellness program for an adolescent with Prader-Willi syndrome. Behav Modif. 2008;32(2):167-181.

56 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Complementary therapies for reducing body weight: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29(9):1030-1038.

57 Tsiros MD, Sinn N, Brennan L, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy improves diet and body composition in overweight and obese adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1134-1140.

58 Cochrane G. Role for a sense of self-worth in weight-loss treatments: helping patients develop self-efficacy. Can Fam Phys 200; 54(4):543–547.

59 Kausman R. Tips for long-term weight management. Aus Fam Phys. 2000;29(4):310-313.

60 Kausman R. If not dieting then what? Melbourne: Allen & Unwin; 2004.

61 National Weight Control Registry. Online. Available: http://www.nwcr.ws/.

62 Catenacci VA, Ogden LG, Stuht J, et al. Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(1):153-161.

63 Flancbaum L, Choban PS, Bradley LR, et al. Changes in measured resting energy expenditure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. Surgery. 1997;122(5):943-949.

64 Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, et al. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):239-246.

65 Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, et al. Psychological symptoms in individuals successful at long-term maintenance of weight loss. Health Psychol. 1998;17(4):336-345.

66 McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: do people who lose weight through various weight loss methods use different behaviors to maintain their weight? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(6):572-577.

67 Shick SM, Wing RR, Klem ML, et al. Persons successful at long-term weight loss and maintenance continue to consume a low-energy, low-fat diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98(4):408-413.

68 McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, et al. What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(2):177-185.

69 Klem ML. Successful losers. The habits of individuals who have maintained long-term weight loss. Minn Med. 2000;83(11):43-45.

70 Klem ML, Wing RR, Lang W, et al. Does weight loss maintenance become easier over time? Obes Res. 2000;8(6):438-444.

71 Klem ML, Wing RR, Chang CC, et al. A case-control study of successful maintenance of a substantial weight loss: individuals who lost weight through surgery versus those who lost weight through non-surgical means. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(5):573-579.

72 Raynor HA, Jeffery RW, Phelan S, et al. Amount of food group variety consumed in the diet and long-term weight loss maintenance. Obes Res. 2005;13(5):883-890.

73 Raynor DA, Phelan S, Hill JO, et al. Television viewing and long-term weight maintenance: results from the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(10):1816-1824.

74 Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Hunger control and regular physical activity facilitate weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2008;18(7):833-840.

75 Daley AJ, Copeland RJ, Wright NP, et al. Exercise therapy as a treatment for psychopathologic conditions in obese and morbidly obese adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2126-2134.

76 Diehl JJ, Choi H. Exercise: the data on its role in health, mental health, disease prevention, and productivity. Prim Care. 2008;35(4):803-816.

77 Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD004366.

78 Weinstein AA, Deuster PA, Francis JL, et al. The role of depression in short-term mood and fatigue responses to acute exercise. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17(1):51-57.

79 Russell-Jones D, Khan R. Insulin-associated weight gain in diabetes—causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(6):799-812.

80 Stanton RA. Nutrition problems in an obesogenic environment. Med J Aust. 2006;184(2):76-79.

81 Haddock CK, Poston WS, Dill PL, et al. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: a quantitative analysis of four decades of published randomized clinical trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(2):262-273.

82 Anderson JW, Vichitbandra S, Qian W, et al. Long-term weight maintenance after an intensive weight-loss program. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18(6):620-627.

83 Miller WC, Koceja DM, Hamilton EJ, et al. A meta-analysis of the past 25 years of weight loss research using diet, exercise or diet plus exercise intervention. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(10):941-947.

84 Miller WC. How effective are traditional dietary and exercise interventions for weight loss? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(8):1129-1134.

85 Neuhouser ML, Miller DL, Kristal AR, et al. Diet and exercise habits of patients with diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease or hypertension. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21(5):394-401.

86 Saris WH, Blair SN, van Baak MA, et al. How much physical activity is enough to prevent unhealthy weight gain? Outcome of the IASO 1st Stock Conference and consensus statement. Obes Rev. 2003;4(2):101-114.

87 Green JS, Stanforth PR, Rankinen T, et al. The effects of exercise training on abdominal visceral fat, body composition, and indicators of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women with and without estrogen replacement therapy: the HERITAGE family study. Metab. 2004;53(9):1192-1196.

88 Sevick MA, Miller GD, Loeser RF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of exercise and diet in overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(6):1167-1174.

89 Weinsier RL, Hunter GR, Desmond RA, et al. Free-living activity energy expenditure in women successful and unsuccessful at maintaining a normal body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(3):499-504.

90 Douglas JG, Ford MJ, Munro JF. Patient motivation and predicting outcome in a hospital obesity clinic. Int J Obes. 1981;5(1):33-38.

91 Vasconcelos MP, Jorge Z, Noble EL, et al. Assessment of an obesity clinic in a center hospital. Acta Med Port. 2004;17(5):359-366.

92 de Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 1):S51-S55.

93 Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, et al. The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(2):104-108.

94 Talbot ML, Jorgensen JO, Loi KW. Difficulties in provision of bariatric surgical services to the morbidly obese. Med J Aust. 2005;182(7):344-347.

95 Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1737.

96 Cretikos MA, Valenti L, Britt HC, et al. General practice management of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Australia. Med Care. 2008;46(11):1163-1169.

97 Wang F, Veugelers PJ. Self-esteem and cognitive development in the era of the childhood obesity epidemic. Obes Rev. 2008;9(6):615-623.

98 McCullough N, Muldoon O, Dempster M. Self-perception in overweight and obese children: a cross-sectional study. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(3):357-364.