43

Nutritional Disorders

Malnutrition

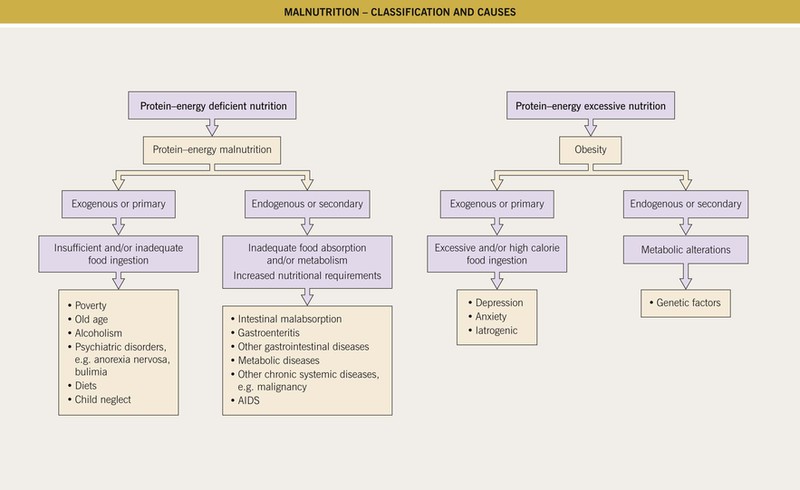

• Malnutrition encompasses both deficiencies and excesses (e.g. obesity) (Fig. 43.1; Tables 43.1 and 43.2).

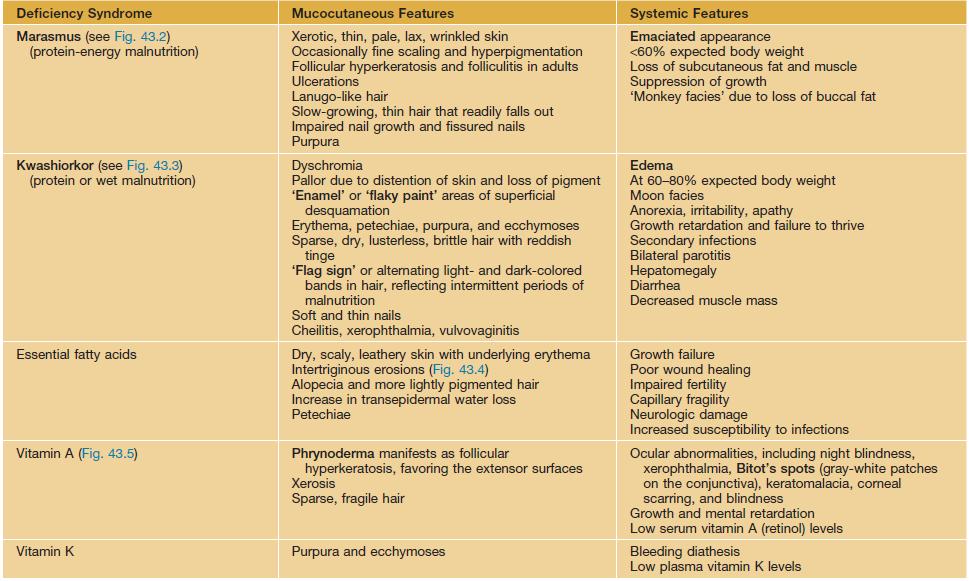

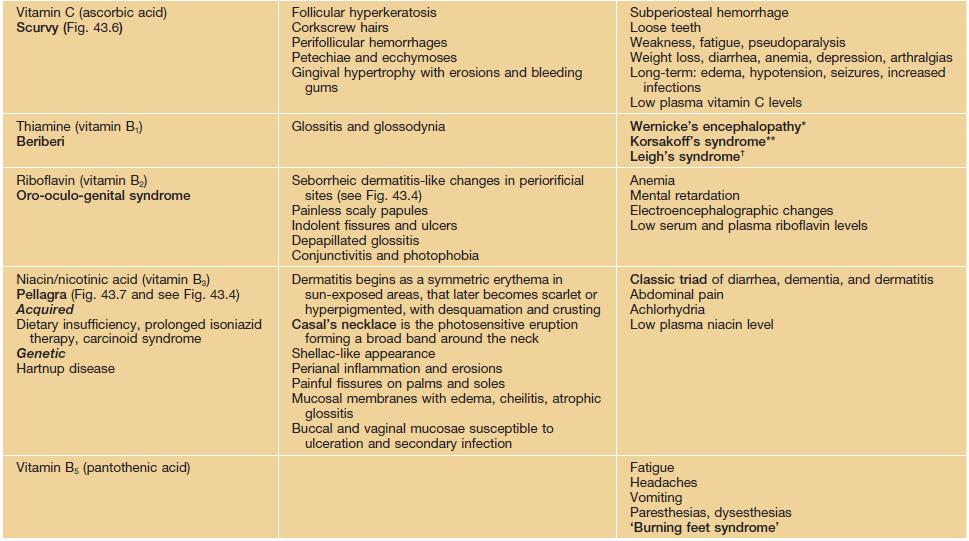

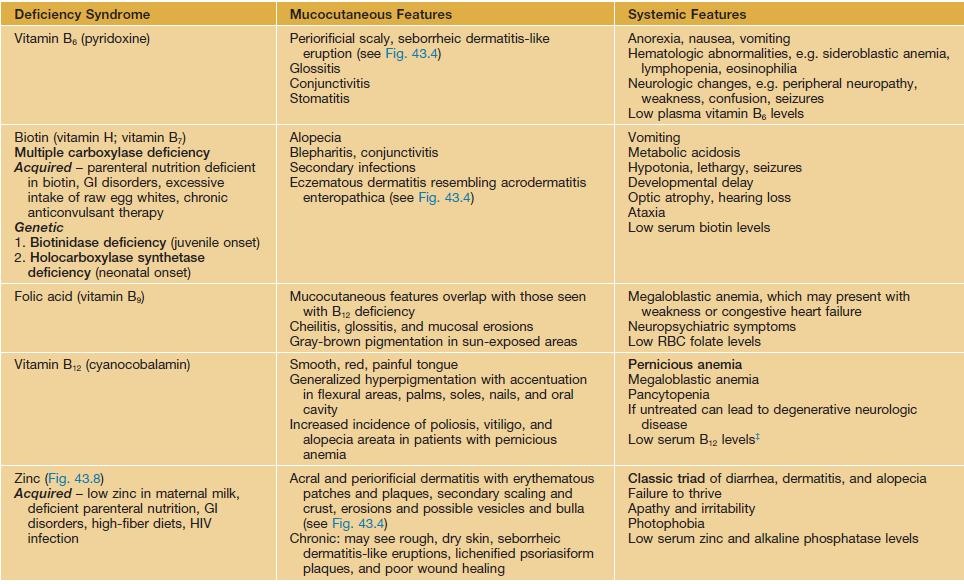

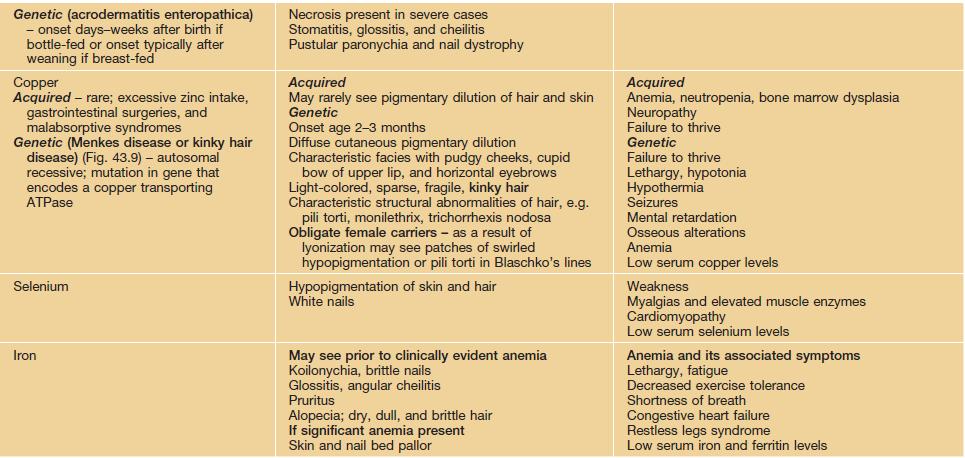

Table 43.1

Malnutrition-deficiency syndromes with mucocutaneous manifestations.

* Wernicke’s encephalopathy characterized by ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, confusion.

** Korsakoff’s syndrome characterized by peripheral neuropathy, memory loss, confabulation.

† Leigh’s syndrome characterized by subacute necrotizing encephalomyopathy; anorexia, weakness, constipation; congestive heart failure; low serum or plasma thiamine levels.

‡ Elevated serum homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels are more reliable indicators of B12 deficiency and are useful to obtain if B12 deficiency is strongly suspected but serum levels of B12 are low-normal.

Table 43.2

Malnutrition-excess syndromes with mucocutaneous manifestations.

| Excess Syndrome | Mucocutaneous Features | Systemic Features |

| Obesity | Plantar hyperkeratosis Acanthosis nigricans Acrochordons Striae distensae Intertrigo Frictional hyperpigmentation Hyperhidrosis Stasis dermatitis Leg ulcers, mostly venous > arterial Lipodermatosclerosis, including the pannus Stasis mucinosis |

Body mass index >30 Hypertension Diabetes and insulin resistance Gastroesophageal reflux disease Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Steatorrhea |

| Vitamin A | Mucocutaneous findings similar to patients on oral retinoids Xerotic, rough, pruritic, and scaly skin Xerotic cheilitis Diffuse alopecia |

Anorexia, weight loss, lethargy Elevated liver enzymes Painful swellings in limbs due to bony changes Radiographic bone changes, e.g. skeletal hyperostosis, extraspinal tendon and ligament calcification |

| Beta carotene (the natural pro-vitamin of vitamin A) Carotenemia |

Carotenoderma (Fig. 43.11) – orange-yellow skin pigmentation primarily in sebaceous gland-rich areas (forehead, nasolabial fold) and in areas with a thicker stratum corneum (palms, soles) Differentiated from jaundice, which has prominent yellow discoloration of the sclerae and mucosae |

|

| Copper Acquired – rare Genetic (Wilson’s disease) – autosomal recessive; mutation in gene that encodes a copper transporting P-type ATPase |

Genetic Kayser–Fleischer corneal rings |

Genetic Liver disease and cirrhosis Dysarthria, dyspraxia, ataxia, and parkinsonian-like extrapyramidal signs |

| Iron Acquired – numerous blood transfusions; excess intake Genetic (type I hemochromatosis) – autosomal recessive; mutation in gene (HFE) that regulates absorption of iron; two most common mutations of HFE gene are C282Y and H63D |

Generalized hyperpigmentation (bronzing) | Chronic fatigue Diabetes Liver disease, cirrhosis Arthritis Cardiac disease Impotence Hypothyroidism |

Marasmus (Protein-Energy Malnutrition)

• Affects infants, children, and adults (Fig. 43.2).

Fig. 43.2 Marasmus. A This child is emaciated and there is both hyperpigmentation and desquamation of the skin. B Multiple purpuric lesions are seen. Courtesy, Ramón Ruiz-Maldonado, MD.

• Is common in the setting of severe food deprivation, often in association with recurrent infections.

Kwashiorkor (Protein or Wet Malnutrition)

• Most commonly affects weaning children, who present with edema (Fig. 43.3) and are at 60–80% of expected body weight.

Fig. 43.3 Kwashiorkor. A This child’s buttocks and legs show tense edema, scaling, and areas of erythema with desquamation. B This child’s arm has edema and superficial epidermal necrosis with an ‘enamel paint’ appearance. Courtesy, Ramón Ruiz-Maldonado, MD.

• Less often it is seen in children older than 5 years of age or adults.

• May also be the presenting manifestation in infants with cystic fibrosis.

Vitamins

• Organic compounds that are biologically active and indispensable for normal physiologic functions.

• Both vitamin deficiency (hypovitaminosis) and excess (hypervitaminosis) can cause dermatologic abnormalities (see Tables 43.1 and 43.2; Figs. 43.4–43.9).

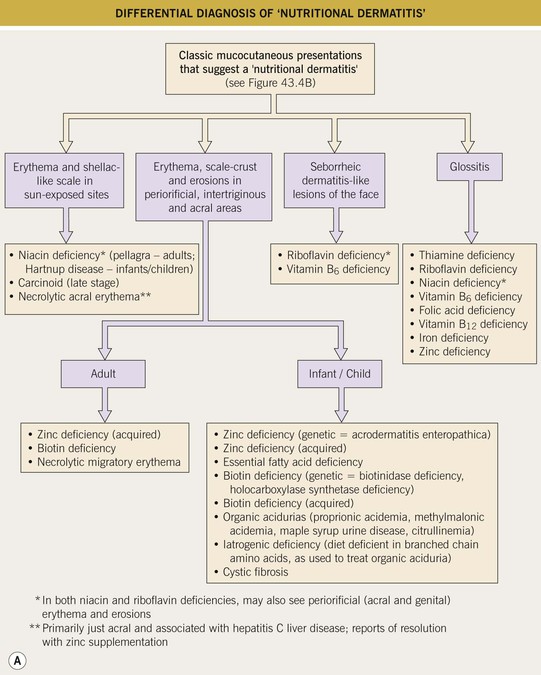

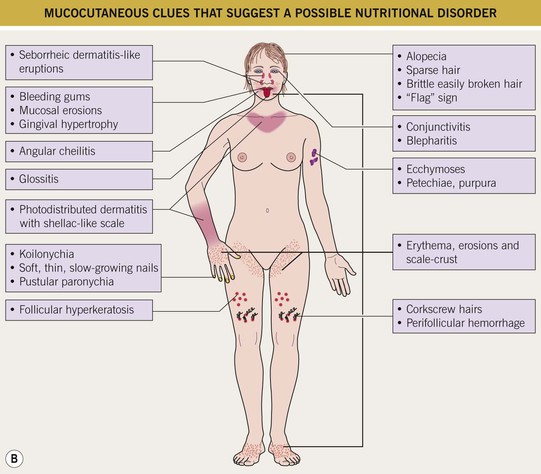

Fig. 43.4 Clinical approach to the patient with a presumed nutritional disorder. A Differential diagnosis of ‘nutritional dermatitis.’B Mucocutaneous clues that suggest a possible nutritional disorder.

Fig. 43.5 Vitamin A deficiency. A Blindness and corneal scarring. B Phrynoderma of the legs. Multiple clusters of follicular papules with central keratotic plugs. A, Courtesy, Peter Erhnstrom, MD; B, Courtesy, Chad M. Hivnor, MD.

Fig. 43.6 Scurvy. A Corkscrew hairs and perifollicular hemorrhage on the lower extremities. B Hemorrhage beneath the buccal mucosa. C Gingival hypertrophy and infection, with loosened teeth. C, Courtesy, Jeffrey Callen, MD.

Fig. 43.7 Pellagra. A Hyperpigmentation with desquamation of the dorsal aspects of the hands and forearms. B Hyperpigmented desquamation of the distal lower extremity. Note the shiny shellac-like appearance on the lateral ankle.

Fig. 43.8 Zinc deficiency. Genetic (acrodermatitis enteropathica) (A–D) and acquired (E, F) forms. Both have erythema with erosions (A, E) as well as crusting (C, E, F) and desquamation (A, D–F). Lesions favor the acral and periorificial sites, and pustular paronychia may also be seen (B). Acrodermatitis enteropathica most often presents in infancy (A, B), but rarely, it is not diagnosed until later childhood, as in the case of this 11-year-old boy (C, D). A–D, courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 43.9 Menkes disease. This child has the characteristic pale skin and sparse kinky hair. Courtesy, Ramón Ruiz-Maldonado, MD.

• Vitamin excess is more common with the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, K, E).

Vitamin D

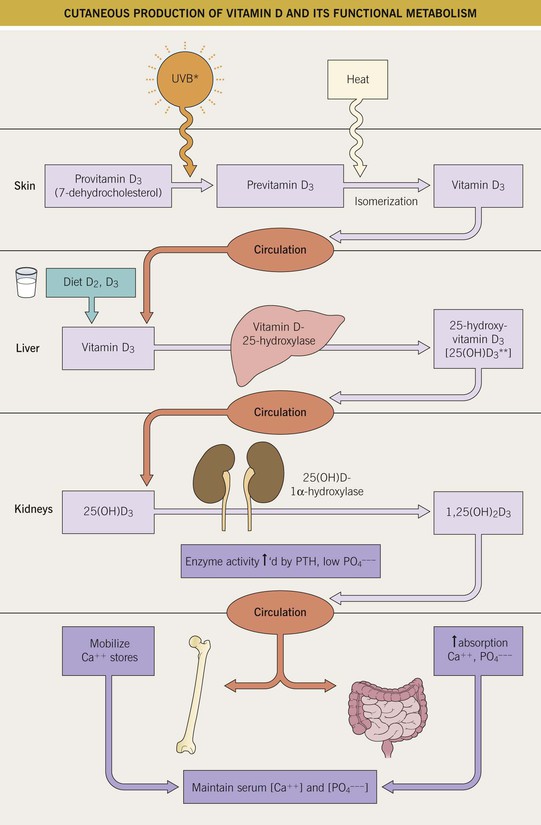

• Initial step in synthetic pathway occurs in the skin (Fig. 43.10); many tissues, in addition to the kidney, have been shown to hydroxylate vitamin D precursors to produce the active form.

Fig. 43.10 Cutaneous production of vitamin D and its functional metabolism. During exposure to ultraviolet B radiation, 7-dehydrocholesterol within the skin is converted to previtamin D3, which is then immediately converted to vitamin D3 in a heat-dependent process. Of note, the heat from excessive sunlight exposure can degrade previtamin D3 and vitamin D3 into inactive photoproducts. Both forms of vitamin D (D3 and D2) are biologically inactive and they require activation in the liver and then the kidney. After binding to carrier proteins, vitamin D is transported to the liver, where it is enzymatically hydroxylated to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the major circulating form of vitamin D. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D is then converted into its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], within the kidney by the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase. Of interest, this final hydroxylation step can also occur in keratinocytes when the enzyme CYP27B1 is upregulated in response to wounding or by Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation from microbial-derived ligands. Serum levels of phosphate, calcium, and fibroblast growth factor 23 can either increase or decrease renal production of 1,25(OH)2D. 1,25(OH)2D decreases its own synthesis via feedback inhibition and decreases the synthesis and secretion of parathyroid hormone by the parathyroid glands. 1,25(OH)2D also enhances intestinal calcium absorption in the small intestine by interacting with the vitamin D receptor–retinoic acid X receptor complex (VDR-RXR) to enhance the expression of the epithelial calcium channel and calbindin-D 9K, a calcium-binding protein. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D is recognized by its receptor in osteoblasts, leading to a series of events that maintain calcium and phosphorus levels in the blood which in turn promotes mineralization of the skeleton. *Most effective wavelength = 300 ± 5 nm. **Measurement of this form most commonly done to assess vitamin D status.

• Individual vitamin D requirements vary depending on an individual’s age, skin pigmentation, underlying diseases, current medications, geographic location, and season of the year; vitamin D receptor polymorphisms may play an important role in disease risk.

• Vitamin D body stores decline with age, during the winter months, and at higher latitudes.

• Oral glucocorticoids inhibit the vitamin D-dependent intestinal absorption of calcium.

• Excess vitamin D, typically resulting from prolonged and excessive intake of vitamin D supplements, can present with anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, muscle weakness, and bone demineralization.

• No specific cutaneous features have been described with vitamin D deficiency or excess.

• Guidelines for vitamin D supplementation have been in flux, but oral supplementation is generally recommended for exclusively breast-fed infants, children who drink less than a liter of fortified milk per day, pregnant women, the elderly, most adults for the prevention of osteoporosis, and individuals on long-term oral glucocorticoids.

Minerals

Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs)

Anorexia/Bulimia

Carotenoderma

• Orange-yellow skin pigmentation (Fig. 43.11) that develops when carotene levels are 3–4 times normal (carotenemia).

Obesity

• Defined as a body mass index (BMI) > 30.

• Acquired obesity is at epidemic levels, especially in high-income populations.

• The cutaneous manifestations of obesity are outlined in Table 43.2.

For further information see Ch. 51. From Dermatology, Third Edition.