CHAPTER 23 Nonunion and Malunion of Distal Humerus Fractures

INTRODUCTION

Nonunion and malunion are two of the most common and challenging complications of distal humerus fractures. Newer internal fixation principles and techniques have improved our ability to achieve stable fixation of complex distal humerus fractures18 (see Chapter 22, Current Concepts in Fractures of the Distal Humerus). However, some fractures will fail to unite, leaving the patient with an unstable, dysfunctional, and oftentimes painful upper extremity requiring additional surgery. Distal humeral malunion is well characterized in the pediatric population after supracondylar fractures (see Chapters 14 and 15) but has not been analyzed as extensively in the adult population.4,8 This chapter reviews the prevalence, risk factors, pathology and treatment options for distal humeral nonunions and the clinical relevance and treatment options for distal humeral malunion.

DISTAL HUMERAL NONUNION

PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS

Distal humerus nonunion with hardware failure and fracture redisplacement usually presents within the first few months after surgery. The prevalence of hardware failure is difficult to determine, because in some cases, hardware failure may allow ultimate fracture healing with residual secondary displacement. In addition, some potential failures of fixation may be avoided by prolonged postoperative immobilization, leading to fracture healing but very limited motion. Nonunion or hardware failure have been reported in approximately 8% to 25% of recent series on distal humerus fractures.6,9,14,19,20

PATHOLOGY

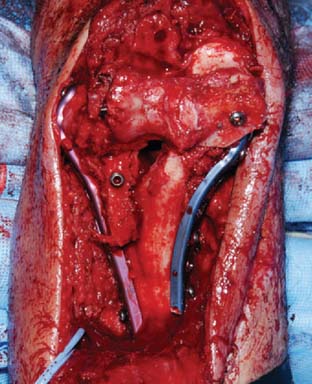

Distal humeral nonunions share a constellation of pathologic findings that need to be addressed at the time of surgery (Fig. 23-1). The nonunion is usually located at the supracondylar level; most of the time, the distal fragments heal in a more or less anatomic position. Progressive bone reabsorption at the nonunion site may lead to severely compromised bone stock. Previously placed hardware may compromise bone stock even further, especially when screw loosening results in a windshield-wiper effect.

Additionally, severe stiffness develops, and when the patient tries to flex and extend the elbow, most motion occurs through the nonunion site, not through the joint.7 Failure to release the associated elbow contracture at the time of fixation of the nonunion may contribute to failure; otherwise, when elbow motion is rehabilitated excessive loads are transmitted through the nonunion site. Not uncommonly, ulnar nerve excursion is compromised by scarring, especially when there has been previous surgery. Excessive motion at the nonunion site may further compromise the function of the ulnar nerve by stretching. Attention should be paid to the ulnar nerve at the time of surgery.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OPTIONS

Imaging Studies

Simple Radiographs

When possible, sequential radiographs should be evaluated to understand the initial fracture pattern, assess the quality of the initial fixation when previously attempted, and determine the amount of bone loss. Recent radiographs will help determine the feasibility of repeated internal fixation versus arthroplasty and the need for structural bone graft and special tools for hardware removal.

Computed Tomography

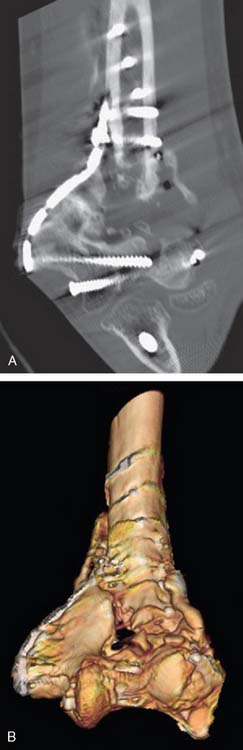

Computed tomography with three-dimensional reconstruction is an invaluable tool when repeated internal fixation is planned (Fig. 23-2), because it provides a better understanding of the remaining bone stock and any degree of associated malunion, and facilitates planning of plate and screw placement in order to achieve the maximum anchorage of the fixation devices.

INTERNAL FIXATION

Surgical Technique

Surgical Approach and Ulnar Nerve Decompression

Most patients with previous surgery will have a posterior midline skin scar that may be used for the revision procedure. If the previous fixation was attempted through separate lateral and medial incisions, most of the time, it is better to ignore those and create a new posterior midline skin incision, unless the skin quality is compromised and wound problems are anticipated. Next, the ulnar nerve should be identified; when a previously transposed ulnar nerve is asymptomatic, additional nerve dissection should be avoided as long as the procedure can be performed without further nerve exposure and the ulnar nerve can be protected and reassessed at the end of the procedure. The nerve should be formally isolated and transposed when it was left in situ during previous surgeries.7 Neurolysis should be considered in patients with a previously transposed symptomatic ulnar nerve.

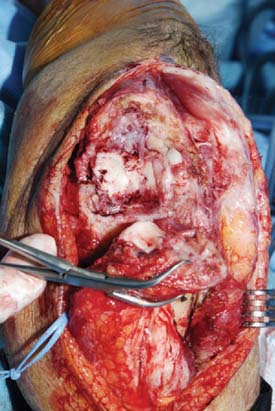

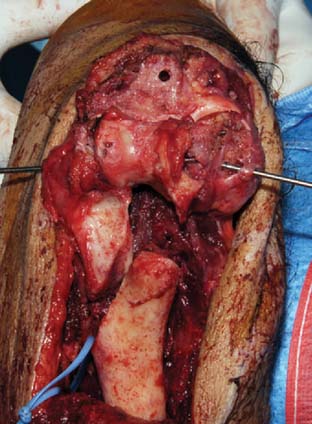

Several deep exposures may be used. A nonunited previous olecranon osteotomy should be used for exposure whenever present. Similarly, when a triceps-reflecting or triceps reflecting anconeus pedicle (TRAP) approach was used for previous surgeries, the same approach should be used if incomplete healing of the extensor mechanism to the olecranon is found at the time of surgery.11 For extra-articular nonunions with an intact extensor mechanism, the so-called bilaterotricipital approach (working on both sides of the triceps without violating the extensor mechanism) provides good exposure while preventing complications such as olecranon nonunion or triceps weakness (Fig. 23-3).2 Olecranon osteotomy provides an excellent exposure and is used by many surgeons for fixation of distal humerus nonunion (Fig. 23-4).15 Alternatively, a triceps-reflecting (Bryan-Morrey or Mayo-modified extensile Kücher) or TRAP approach is selected when the decision to proceed with fixation versus arthroplasty will be taken intraoperatively.3 Once the deep exposure is complete, tissue should be sent routinely for pathology and microbiology.

Capsular Release

Capsular contracture is a constant feature of distal humerus nonunions. Failure to release the contracture will limit final range of motion and increase the stress transmitted to the nonunion site, which may contribute to fixation failure. The posterior capsule and posterior band of the medial collateral ligament can been accessed and resected easily through any of the posterior approaches mentioned earlier. The anterior capsule may be released through the nonunion site (Fig. 23-5). Care should be taken to identify and protect the radial and median nerves at the time of the anterior capsular release. The anterior band of the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament complexes should be preserved, along with the muscular attachments on the medial and lateral epicondyles, which are responsible for most of the blood supply to the distal segments.

Fixation Technique and Bone Grafting

The fixation technique that we recommend for internal fixation of distal humerus nonunions follows the same principles, objectives, and steps described for fixation of acute distal humerus fractures in the previous chapter (see Chapter 22).18 However, bone reabsorption at the nonunion site usually makes it difficult to apply compression at the supracondylar level if the reduction is anatomic, and the concept of metaphyseal shortening (see Chapter 22) often needs to be applied.12

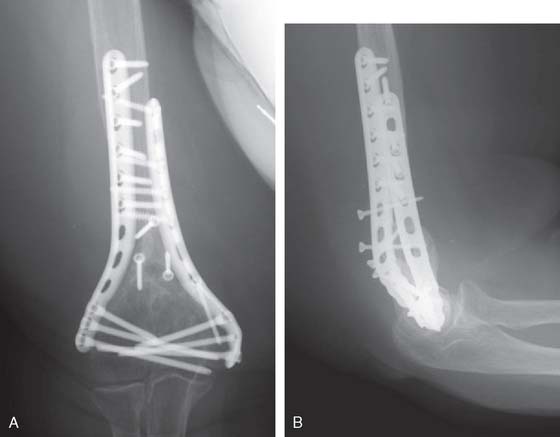

Two parallel plates are then applied medially and laterally, and fixed with multiple distal long screws, which most of the time will interdigitate and interlock, increasing the stability of the construct (Fig. 23-6). Compression at the nonunion site is achieved by a combination of maneuvers including the use of a large reduction clamp, proximal screw insertion in the compression mode, and slight undercontouring of the plates. Cancellous bone autograft or a bone graft substitute is then placed at the nonunion site to promote bone healing. Our preference is to fashion two thin corticocancellous plates from the iliac crest and fix them with one or more screws across the nonunion site on the medial and lateral columns (Figs. 23-6 and 23-7).

Outcome

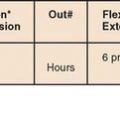

There are several studies on the results of internal fixation for distal humerus nonunions. Some articles have included a wide spectrum,5 from delayed unions and nonunions affecting one column to infected nonunions with bone loss and associated deep infection. Other authors have studied more specific group of patients, such as flail or osteochondral nonunions.16,17 It is important to understand the information summarized below as it pertains to the particular case presenting for treatment.

Early treatment attempts for distal humerus nonunions were somewhat discouraging. Mitsunaga et al10 reported on 25 patients treated with internal fixation; close to 30% of the patients required additional surgery for revision fixation or bone grafting. Ackerman and Jupiter1 published a higher union rate of 94% in a series of 20 patients, but the functional results were fair or poor in 65% of the cases, and only one patient was considered to have an excellent result. The authors noted that most patients continue to have a major long-term disability despite achieving successful union.

The results of internal fixation for distal humerus nonunions were improved with the introduction of better fixation constructs and attention to capsular release and the ulnar nerve.7 The more recent literature on the outcome of internal fixation for distal humerus nonunions shows improved overall results,5 but there are some specific subsets of patients in which internal fixation continues to provide suboptimal outcomes.16,17

Helfet et al5 recently published their experience with internal fixation in 52 patients presenting with a delayed union (13 patients) or a nonunion (39 patients) of the distal humerus. Most (39 patients) but not all patients had undergone previous failed surgery. There was a wide range of patterns of nonunion included in this study. Only 13 nonunions were intercondylar; the remaining were supracondylar in 27 patients, transcondylar in 6 patients, and lateral or medial condylar in 6 patients. Union was achieved in all but one patient, and the average final arc of motion was 94 degrees. However, additional surgery was performed in approximately 30% of the patients, mostly to improve motion, address the ulnar nerve, or remove prominent hardware.

Ring et al16,17 have analyzed the outcome in two specific subsets of distal humerus nonunions. In their first study, these authors reported on the outcome of so-called unstable nonunions, defined as those in which the hand and the forelimb cannot be supported against gravity. Union was achieved in 12 of the 15 patients included in their study, but additional surgery was performed in six of the 12 elbows with healing, again to improve motion, address the ulnar nerve, or remove hardware. Osteochondral nonunions were addressed in a separate paper including only three patients who all achieved union and improved motion without evidence of osteonecrosis.16,17

DISTAL HUMERAL MALUNION IN THE ADULT PATIENT

The clinical features and treatment options for distal humerus malunions have been studied and reported mostly in the pediatric population, as detailed in Chapters 15 and 16. Malunion also occurs in the adult population, but there is limited information on the evaluation and treatment of distal humerus malunion in adults.4,8

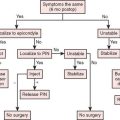

EVALUATION

Plain radiographs are useful mostly to assess the status of the articular cartilage and identify associated pathology (Fig. 23-8). In addition, marked deformity is easily identified in plain radiographs, but computed tomography with three-dimensional reconstruction represents the ideal imaging modality to understand the deformity and determine if there is an associated nonunion of part of the articular surface, because some patients will present with a combination of nonunion on one side of the joint and malunion on the other side of the joint.8 The malunion may be mostly extra-articular, mostly intra-articular, or a combination of the two. The evaluation should be completed with studies to identify infection in patients with previous surgery, risk factors or suspicious findings on the history and physical exam.

TREATMENT

Patients with symptomatic distal humerus malunion may be offered several alternatives (Box 23-1). Osteotomy for correction of extra-articular and intra-articular deformities is appealing because it provides the potential to preserve the native joint and improve pain and motion. However, some patients may present with severe joint destruction not amenable to osteotomy. Arthroplasty may represent a good alternative for older patients willing to limit their upper extremity use and prevent mechanical failure. When moderate extraarticular deformity limits motion secondary to impingement of the proximal ulna and radius with the deformed distal humerus, recontouring of the distal humerus by selective removal of bone provides a reasonable alternative with relatively low morbidity. Joint fusion may be considered for patients with severe pain who are not candidates for other surgical alternatives, but most patients with limited motion secondary to a distal humerus malunion are reluctant to have their elbow fused.

Osteotomy

Patients with an extra-articular malunion of the distal humerus may benefit from extra-articular osteotomy. Correction of the malunion may improve range of motion and cosmesis. In addition, varus malunion may be associated with progressive ulnar neuropathy as well as gradual attrition of the lateral collateral ligament complex and tardy posterolateral rotatory instability.13 Closing-wedge osteotomies are usually preferred because humeral shortening is relatively well tolerated. Medial or lateral translation of the distal fragment should be considered to avoid a serpentine aspect of the distal humerus. Usually, extra-articular osteotomies are performed through a bilaterotricipital approach and fixed with medial and lateral plates (Fig. 23-9). Capsular release and ulnar nerve transposition may be associated as needed.

OUTCOME

There is very limited information about the outcome of surgical correction of distal humerus malunion. Cobb et al4 reported on three patients treated with an intra-articular derotational opening-wedge osteotomy for a distal humerus malunion. Motion was improved in all three patients, but one required conversion to interposition arthroplasty.

More recently, McKee et al.8 reported on a heterogeneous group of 13 patients with intra-articular distal humerus malunion or nonunion following fracture. Six fractures had healed in a malunited position, two elbows presented a combination of lateral malunion and medial nonunion, and the remaining five presented a nonunion. An intra-articular osteotomy was performed in the eight patients with malunion; results were rated as satisfactory in seven patients.

The results of arthroplasty in patients with distal humerus malunion are difficult to dissect out of the studies analyzing arthroplasty for the sequelae of trauma (see section on arthroplasty). As noted, the main concern is the increased rate of polyethylene wear found in patients with preoperative angular deformity.

1 Ackerman G., Jupiter J.B. Non-union of fractures of the distal end of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1988;70:75.

2 Alonso-Llames M. Bilaterotricipital approach to the elbow. Its application in the osteosynthesis of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1972;43:479.

3 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow. A triceps-sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1982;166:188.

4 Cobb T.K., Linscheid R.L. Late correction of malunited intercondylar humeral fractures. Intra-articular osteotomy and tricortical bone grafting. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1994;76:622.

5 Helfet D.L., Kloen P., Anand N., Rosen H.S. Open reduction and internal fixation of delayed unions and nonunions of fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003;85-A:33.

6 Henley M.B. Intra-articular distal humeral fractures in adults. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1987;18:11.

7 Jupiter J.B., Goodman L.J. The management of complex distal humerus nonunion in the elderly by elbow capsulectomy, triple plating, and ulnar nerve neurolysis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:37.

8 McKee M., Jupiter J., Toh C.L., Wilson L., Colton C., Karras K.K. Reconstruction after malunion and nonunion of intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus. Methods and results in 13 adults. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1994;76:614.

9 McKee M.D., Wilson T.L., Winston L., Schemitsch E.H., Richards R.R. Functional outcome following surgical treatment of intra-articular distal humeral fractures through a posterior approach. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000;82-A:1701.

10 Mitsunaga M.M., Bryan R.S., Linscheid R.L. Condylar nonunions of the elbow. J. Trauma. 1982;22:787.

11 O’Driscoll S.W. The triceps-reflecting anconeus pedicle (TRAP) approach for distal humeral fractures and nonunions. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2000;31:91.

12 O’Driscoll S.W., Sanchez-Sotelo J., Torchia M.E. Management of the smashed distal humerus. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2002;33:19. vii

13 O’Driscoll S.W., Spinner R.J., McKee M.D., Kibler W.B., Hastings H.2nd, Morrey B.F., Kato H., Takayama S., Imatani J., Toh S., Graham H.K. Tardy posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow due to cubitus varus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 2001;83-A:1358.

14 Pajarinen J., Bjorkenheim J.M. Operative treatment of type C intercondylar fractures of the distal humerus: results after a mean follow-up of 2 years in a series of 18 patients. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:48.

15 Ring D., Gulotta L., Chin K., Jupiter J.B. Olecranon osteotomy for exposure of fractures and nonunions of the distal humerus. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2004;18:446.

16 Ring D., Gulotta L., Jupiter J.B. Unstable nonunions of the distal part of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1040.

17 Ring D., Jupiter J.B. Operative treatment of osteochondral nonunion of the distal humerus. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2006;20:56.

18 Sanchez-Sotelo J., Torchia M.E., O’Driscoll S.W. Complex distal humeral fractures: internal fixation with a principle-based parallel-plate technique. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007;89:961.

19 Sanders R.A., Raney E.M., Pipkin S. Operative treatment of bicondylar intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus. Orthopedics. 1992;15:159.

20 Soon J.L., Chan B.K., Low C.O. Surgical fixation of intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus in adults. Injury. 2004;35:44.