Chapter 189 Nonoperative Management of Neck and Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) usually is benign and self-limiting. Health care providers are in a position to improve patient response to back symptoms greatly by providing reassurance, encouraging activity, and emphasizing that more than 90% of LBP complaints resolve without any specific therapies.1

LBP is second only to upper respiratory problems as the reason why patients visit a primary care provider.2 Pain of spinal origin will affect 70% to 85% of the population at some point in their lives and is the most common cause of disability in patients younger than 45 years of age.3 It accounts for a large fraction of the health care budget. LBP treatment costs increased from $4.6 billion in 1977 to $11.4 billion in 1997. In 2005, an estimated $85.9 billion was spent in the United States.4 Annually, $20 to $50 billion is spent on workers’ compensation claims, with 10% of patients with back pain accounting for 85% to 90% of the costs.3,5,6 Although most adults experience low back and neck pain, only a small percentage (~1%) require surgery.

In 2005, 15% of adults in the United States reported back problems, compared with 12% in 1997.4 As more people seek treatment for back pain, the cost per individual is rising. One study4 found that the inflation-adjusted cost per study subject rose from $4695 in 1997 to $6096 in 2005. The natural history of LBP suggests that the passing of time is the best treatment, as 90% of cases resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks to 3 months of onset.3,7 LBP affects men and women equally, and the onset most often occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 years. Eighty percent of the population will experience acute LBP at least once, and 30% of this group will become chronic sufferers. The annual prevalence ranges from 14% to 45%.

Etiology

The etiology of spine pain is multifactorial. The cause of LBP may originate within spinal structures such as ligaments, facet joints, vertebral periosteum, paravertebral musculature and fascia, blood vessels, the anulus fibrosus, and spinal nerve roots. Disease states or processes such as cancer, infection, or musculoligamentous injuries also are causes of spinal pain, as are degenerative processes of the spine such as spinal canal stenosis, foraminal stenosis, and disc disease. No pathoanatomic diagnosis can be given to 85% of patients with isolated spine/LBP because of the poor association between symptoms and imaging results.6 “Strain” and “sprain” are commonly used as catch-all diagnoses for generalized LBP in the absence of major red flags.

Classification of Spinal Pain

Mechanical Pain

Mechanical spinal pain is generally described as deep and agonizing. It is worsened with loading of the spine during activity and relieved or alleviated by unloading of the spine with rest. Mechanical pain has a deep and aching quality. It usually is associated with degenerative conditions seen in older adults or the development of a pseudarthrosis after a failed fusion. It also may be present with tumor.8

Myofascial Pain

Myofascial pain is consistent with “muscle spasm.” Patients with significant trapezius spasm will describe tension-type headaches. Myofascial pain usually is self limiting and responds well to stretching exercise and muscle relaxants. Patients with underlying instability or mechanical pain often describe associated myofascial pain. “Strains” and “sprains” of the neck or low back are catchall terms used for nonspecific spine pain and usually are grouped within this category.8

Risk Factors

Adults are at risk of an episode of back pain regardless of timing, activity, or environment. However, many factors may make one patient’s risk comparatively higher than another. Risk factors for low back and neck pain include advancing age up to 55 years, Caucasian race, living in the western United States, prolonged driving of a motor vehicle, heavy lifting and twisting, overexertion, prolonged sitting or standing, trauma, obesity, poor conditioning, and smoking.9–12 In addition, there is a high prevalence of major depression in patients with chronic pain.13

Special attention should be given to the definite link between psychological variables and pain of spinal origin that has been discussed in the literature. Recognition of psychological variables emphasizes the need to highlight the multidimensional approach needed for caring for individuals with spine pain. Psychological distress can more than double the risk of low back pain.14 Stress, distress, anxiety, mood, emotion, cognitive functioning, personality factors, and abuse have been shown to be linked to the onset of back and neck pain. Psychological variables may play a role not only in chronic pain but also in the etiology of the onset of acute pain.15 Resultant disability caused by LBP may be a psychological stress-related disorder.16 A complex pathway of physical work demands, the patient’s reaction to the psychosocial environment, and the unique attributes of the person may affect physical loading on the spine, increasing the risk of LBP.17

Prevention

Ultimately, the best way to prevent LBP is to reduce risk factors. Patient education focusing on the prevention of episodes of LBP should include participation in an exercise program consisting of aerobic exercise, stretching, and strengthening exercise.18 Exercises showed strong positive results as an effective preventive measure against back and neck pain.19 Stretching and strengthening exercises may be done at home, thereby helping to reduce the monumental financial burden on the health care system. Smokers should be instructed to quit, because smokers have more severe symptoms that are present a greater portion of the day compared with nonsmokers.20 Another preventive intervention includes maintaining weight appropriate to height, because obesity is positively linked to LBP.12 Linton and van Tulder19 reviewed 27 controlled trials regarding interventions for the prevention of back and neck pain. Their review found that back schools were not effective for prevention. Evidence showed that lumbar supports were consistently negative, and there is strong evidence that they are not effective. Neither ergonomic interventions nor risk factor modification could be considered because of a lack of quality controlled trials and subsequent evidence.

Current Treatment Therapies

Points for Patient Education

The first step in management of spine pain is educating the patient with regard to the probable cause of his or her pain, including a brief explanation of the anatomic pain generators. By understanding the cause of the pain, patients are more likely to become active participants in their treatment plan. Patients should be encouraged to accept responsibility for managing their recovery rather than expecting the provider to provide an easy fix. The patient recovery process is then directed by activity level rather than level of pain as a limitation.1 The second step is to discuss the process of eliminating or reducing risk factors for future episodes of LB or neck pain and to reinforce the patient’s lifetime commitment to working toward this goal. Third, the patient must be reassured that LBP is a normal and common occurrence, has an excellent prognosis, and, in most cases, abates with the passage of time. Fourth, the patient should be informed that because LBP has a multifactorial etiology, more than one intervention or treatment method probably will be necessary. Finally, whichever treatment methods are chosen, follow-up care is essential, whether the doctor initiates the treatment or refers the patient to another physician or health care provider.

Patients should be encouraged to return to work as soon possible, because this is a predictor for positive outcomes and relief of back pain and helps to reassure patients that they will be able to resume their usual activities/lifestyle.1 Although many invasive and noninvasive therapies are intended to cure or manage LBP, no strong evidence exists to suggest that any single therapy is able to accomplish this as successfully as a therapy that focuses on restoring functional ability without focusing on pain. Patients should be aware that returning to normal activities usually aids functional recovery.1

Medication Therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to be effective for short-term improvement in patients with LBP.1 No single type of NSAID is more effective than any other.21 Evidence suggests analgesics are not more effective than NSAIDs.22 Evidence has shown that muscle relaxants reduce pain intensity and that the different types are equally effective. Evidence for the use of muscle relaxants for LBP lasting longer than 3 months is lacking. However, the results show symptom relief when compared with a placebo.22 Evidence shows more effective symptom relief when medications are used in conjunction with NSAIDs and are prescribed around the clock rather than on an as-needed basis.6,23

Antidepressant drug therapy may be beneficial, because one third of patients who suffer from chronic LBP also have depression and may benefit. Antidepressants may decrease the patient’s perception of pain by treating underlying depression and improving sleep.1,24 Hypotheses of similarities between the physiology of pain and depression exist; therefore, there may be beneficial effects of antidepressant drug therapy on pain separate from the drug’s antidepressant effects.25 Treating patients who do not have signs and symptoms of clinical depression is controversial. However, tricyclic antidepressants have been shown to be effective in the treatment of nondepressed patients with neuropathic-type pain and significantly increased pain relief over placebo without a significant difference in functioning.26,27

Exercise Therapy

Aerobic Activity

Recently, aerobic exercise has shown the best evidence of efficacy among the exercise regimens, whether for acute, subacute, or chronic LBP.1 Benefits of aerobic exercise include weight loss and psychological effects of improved mood and lessened anxiety. The sense of well-being and accomplishment achieved from a planned aerobic exercise program creates a positive self-image and increases the level of motivation and commitment to the prescribed therapy. Some researchers have suggested that particular types of high-impact exercise should be avoided because of the potential for raising intradiscal pressure.28 This stance, however, has not been backed by objective data. It has been shown that patients participating in an aerobic exercise program received few prescriptions for pain, were given fewer physical therapy referrals, and had improved mood states and lessened depression.29

Stretching Exercises

The literature is inconclusive as to whether or not aggressive stretching exercises help to reduce low back pain.1 Stretching exercises help to improve the extensibility of muscles and other soft tissues, and to reestablish normal joint range of motion. Pain commonly limits mobility. Muscle spasm, or sprain, also may be present. Stretching is thought to maintain mobility and reduce spasm. Kraus et al.,30 in a study of the effects of stretching exercises on back pain, found that nearly 80% of people with chronic back pain who entered the program reported improvement at the end of a 6-week training session.31 More recent investigations have found that unless the exercises are continued, the benefit of stretching exercise may be lost.32 Patient compliance is, again, a large determinant in the outcome.

Isometric Exercises

Isometric exercises and exercise regimens have enjoyed significant popularity. Several studies33,34 suggest that isometric flexion offers the best relief of pain and improved function for LBP and neck pain. With regard to LBP, the rationale in these studies was that flexion (1) widened intervertebral foramina and facet joints, reducing nerve compression; (2) stretched hip flexors and back extensors; (3) strengthened abdominal and gluteus muscles; and (4) reduced dorsal fixation of the lumbosacral junction. Concerns have been raised over the use of flexion exercises, specifically regarding substantial increases in intradiscal pressure that may aggravate bulging or herniation of an intervertebral disc. Randomized controlled trials have shown conflicting results.35–37 However, core strengthening exercises are recommended after the acute pain has diminished.1

McKenzie advocated extension exercises, because they limit the risk of aggravating nerve root compression from extrusion of a disc fragment. This program is complicated and is individualized according to the patient’s symptoms. However, there is a very high noncompliance rate. McKenzie exercises are helpful for pain radiating below the knee.38

Mounting evidence indicates that weak muscles are associated with back and neck pain.31,39,40 Therefore, strengthening exercises may reduce or eliminate back and neck pain. The supporting muscles of the spinal column provide support and prevent excessive or abnormal spinal movement. Activities that stress the spine without simultaneously strengthening muscles that support the spine (i.e., the ventral and dorsal support muscles) could result in stress/muscle strength imbalance. This could result in an application of excessive stress to the spine, thus accelerating degenerative changes and worsening pain.

Bed Rest

Bed rest for the treatment of acute episodes of LBP is controversial. Contrary to what was once recommended, bed rest is not effective in the treatment of LBP and may actually be harmful as treatment for an acute episode of nonspecific LBP.21,41–43

Bed rest has significant disadvantages, including its psychological association with a severe illness that requires many days in bed. This may lead to depression, exacerbation of pain, and a predisposition to diminished effort in an exercise program. Deconditioning, with muscle atrophy (1–1.5% per day44), cardiopulmonary function loss (15% in 10 days),45 and bone mineral loss, occurs relatively rapidly. In addition, medical complications, including deep venous thrombosis and pneumonia, are more common with bed rest.

Smoking Cessation

Smokers have been found to have more severe pain that is present for longer periods during the day when compared with nonsmokers, and smoking may exacerbate episodes of pain.20,46 Smokers should be encouraged to quit, because this may reduce the severity as well as duration of LBP.10,11

Appropriate Weight for Height

Obesity has a modest positive association with the chronicity as well as the recurrence of LBP.12 Obese patients have been shown to have more severe pain symptoms than nonobese patients.47

Bracing

Bracing does diminish and may alleviate acute LBP because it supports the muscles of the spine. However, long-term use of bracing may lead to atrophy of these supporting muscles, ultimately resulting in a chronic pain syndrome. Wearing a brace may lead to weakening the supportive muscles of the spine.48 Lumbar braces in the workplace have been shown to have no effect on muscle fatigue or lifting.49 There is little evidence in the literature for the effectiveness of orthoses in the treatment of LBP.21 Ultimately, lumbar braces probably serve best as a reminder to the patient to use correct spine mechanics when performing activities such as lifting and bending.23

Traction

Theoretically, traction is used to stretch the back and neck, distracting the vertebrae, and thereby potentially reducing protrusion of a bulging or herniated disc. Approximately 1.5 times a patient’s body weight is needed to develop distraction of the vertebral bodies. This may cause compliance issues, because it may be burdensome and time consuming. Conventional traction has not been shown to be efficacious for either acute or chronic back or neck pain,34,50 and, therefore, the use of traction is not recommended for the treatment of back or neck pain symptoms.

Adjunct Therapies

The etiology of LBP is multifactorial, as is its treatment. Patients in a passive modality-intensive program have poor functional outcomes when compared with patients in an exercise-based program.51 Therefore, adjunct therapies should be used in conjunction with conservative treatment therapies and not as a sole treatment for pain of spinal origin.

Injection Therapy

The types of injection therapy most commonly used for LBP and radiculopathy include trigger point injections (TPIs) and nerve root, epidural, and facet joint injections (FJIs). All injection therapy should be used in conjunction with stretching and strengthening exercises to maximize the benefit of the effect of reduced pain, thereby increasing function. Multiple reviews of controlled trials show that the evidence for use of epidural steroid injections is conflicting, and they probably should not be used for acute or chronic LBP.22,23,34 Limited evidence supports trigger point therapy as a therapeutic treatment for LBP. TPI should be prescribed for muscle spasm only when a patient has not responded to 4 to 6 weeks of medication and exercise therapy.23 FJIs are not indicated during the first 4 to 6 weeks of treatment of LBP. FJI therapy is controversial, and, once again, evidence for its use is lacking. When compared with placebo, no significant difference in pain relief was noted.27 If FJI therapy is prescribed, it should be used in patients for whom surgery is not an option. FJIs may help patients who complain of LBP with walking, standing, and extension activities and have an otherwise normal neurologic examination.23

Ice and Heat Therapy

Within the first 24 hours of the back or neck pain caused by a benign injury, alternating treatments of ice and heat for 20-minute periods can be effective in reducing inflammation.7 When used in conjunction with home exercise therapy, patients may be instructed to use heat to warm the affected muscles prior to home exercise and ice packs after home exercise therapy for symptomatic relief. Insufficient data exist for the treatment of acute and chronic neck pain with thermotherapy.34

Continuous Low-Level Heat Wrap Therapy

Heat wrap therapy has been shown to be effective in LBP. It also has been shown to be superior to ibuprofen or acetaminophen for relief of LBP. The heat wrap is worn around the lumbar region and secured with Velcro. It heats the area to 104°F for up to 8 hours.52

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is used as a deep-heating modality because it reaches tissue depths that superficial heat cannot reach. Its use is not recommended for acute inflammatory conditions, because it may only increase the inflammatory response.23 The literature lacks reports of any controlled research trials on its use for or against the treatment of LBP. Reviews of the literature found no clinical benefit for the use of ultrasound for chronic neck pain and no evidence for acute neck pain.34

Massage Therapy

Pennick and Sinclair found that massage therapy improved symptoms and function and was more effective when used in combination with a program for the treatment of LBP.27 Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.53

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Several studies have shown no clinically or statistically significant effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in the treatment of acute or chronic LBP or of acute neck pain.22,27

Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) is a combination of acupuncture and TENS therapy. The evidence is insufficient to support its effectiveness for relief from LBP.1

Chiropractic or Manual Therapy

Modest evidence shows that chiropractic/manual therapy is more effective than placebo but not more effective than other forms of therapies for patients with acute LBP.21,54 For the treatment of chronic LBP, chiropractic/manual therapy has been shown to be more effective than traditional therapies.21

Acupuncture

Limited discussion with regard to acupuncture has been published in the spine literature. However, it has been shown to have positive effects on LBP and return to work.55,56

Bipolar Permanent Magnet Therapy

Bipolar permanent magnet therapy has been shown to have no effect on LBP.57

Whole-Body Vibration Exercise

Whole-body vibration exercise significantly reduced pain sensation in a study group of patients experiencing LBP. This new type of exercise elicits muscular activity through stretch reflexes.58 At one time, continuous vibration was considered a cause of LBP; now, however, it is considered to be helpful in the treatment of LBP.

Intradiscal Electrothermal Anuloplasty

Intradiscal electrothermal anuloplasy (IDET) is a minimally invasive procedure that has received mixed reviews because of its uncertain mechanism of action and is not yet widely accepted. IDET is recommended for patients who have discogenic pain, in whom other conservative treatment therapies or modalities have failed, and who may be candidates for lumbar fusion surgery.59 Provocative discography must be performed prior to the IDET procedure itself to determine whether or not an intervertebral disc is the source of LBP. Discography is yet another cause of controversy. Evidence for the reliability of discography as a diagnostic method for degenerative disc disease is mixed.60,61 In addition, there have been several reports of previously asymptomatic patients developing long-term back symptoms after diagnostic provocative discography.59,62

Overall, patients should be encouraged to return to their normal lifestyle as quickly as possible, taking into consideration the type of work the person performs. Light multidisciplinary treatment for LBP is a cost-effective treatment for LBP. This type of treatment includes evaluation by a physical therapist, a nurse, and a psychologist, if necessary. The patient is then instructed on exercise, lifestyle, and ways to overcome the fear that the pain will recur.63

Components for Aggressive Nonsurgical Management of Back Pain

Stretching Exercise

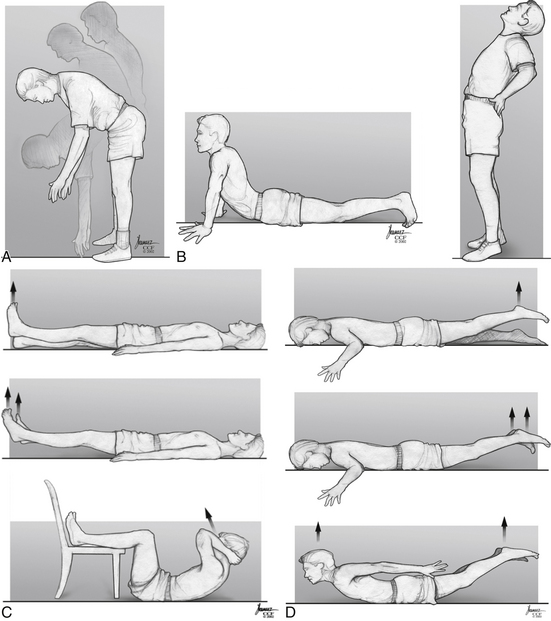

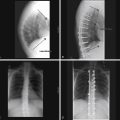

The augmentation of flexibility is an integral component of the program. The spine of a patient with mechanical instability should be thought of as akin to a frozen joint associated with immobilization. Flexibility can be improved with stretching, and progress can be quantitatively monitored. Toe touching can be monitored by asking patients to reach for their toes with knees locked and to hold the lowest position achievable for 20 seconds. The distance from the floor is measured and recorded. Bouncing is discouraged. Documentation is mandatory. Progress is encouraged. In fact, lack of progress may very well be a manifestation of a lack of adequate motivation. Other exercises include extension; however, they are not as easily quantified and monitored (Fig. 189-1). Less aggressive exercises may be more appropriate initially.

Strengthening Exercise

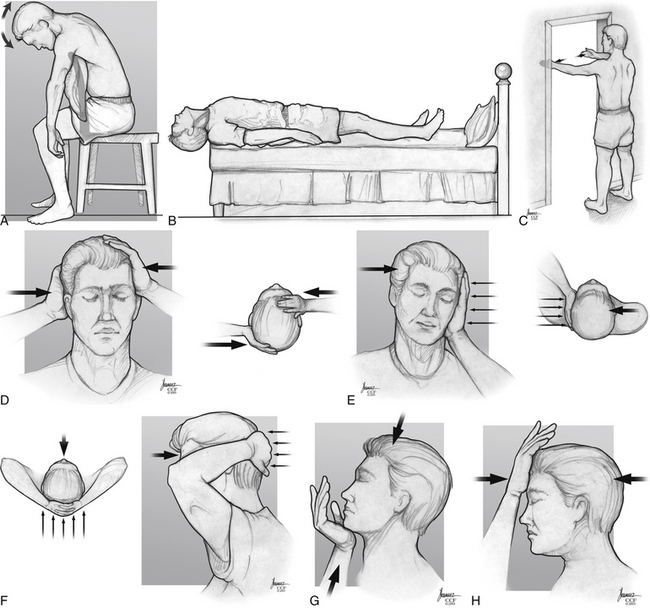

The specific muscle groups to be exercised include the dorsal paraspinous muscles and the abdominal muscles. Specific exercises include supine leg lifts progressing to sit-ups for abdominal muscle strengthening and prone leg lifts progressing to the airplane or rocking chair exercise for paraspinous muscle strengthening (see Fig. 189-1). Initially, less aggressive exercises may be more appropriate. Similarly, strengthening exercises may be used for cervical pain (Fig. 189-2).

Patient Education

An essential component of the program is patient education. If patients understand the importance of their active participation, it is more likely that they will achieve the goal of the program. Documentation of patient progress also is imperative for longitudinal monitoring purposes. If patients cannot or refuse to participate, they have demonstrated their relative inability to succeed in a program such as that just outlined and should, perhaps, seek relief elsewhere.

In conclusion, due to the multifactorial etiology of LBP and neck pain, the treatment therapies and modalities also should be multiple. The natural history of LBP shows that most patients will recover from their symptoms within a relatively short period of time; patients must be reassured that this is the case. Early identification of risk factors and implementation of preventive measures seem to be the most effective methods to avoid future episodes of LBP and neck pain and would greatly affect the huge financial strain on the health care system. Interestingly, research has provided evidence that LBP and neck pain often are manifestations of psychological stressors. Psychological variables cause patients to have more severe pain. Bed rest is not recommended for episodes of acute or chronic LBP. Return to normal daily activities is the best treatment, along with the appropriate use and management of NSAIDs for acute episodes of LBP. Isometric exercises are the best treatment for neck pain. Aerobic activity has been shown to be the best exercise regimen for LBP. Weight control, smoking cessation, and back exercises have been shown to reduce pain level and duration as well as aid in the treatment of chronic LBP. Many therapies and modalities in the treatment of back and neck pain exist; many have been shown to be effective and others not effective at all. However, many of the effective methods may have benefited, as the patient has, from the passing of time, and the symptoms may have improved in spite of the prescribed therapy. Larger and repeated studies are necessary to further the advancement of appropriate prevention and treatment of episodes of LBP and neck pain. Extensive patient education campaigns are needed to reduce risk factors.

Hegmann K.T. Low back disorders. In: Glass L.S., editor. Occupational medicine practice guidelines: evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers. ed 2. Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM); 2007:366.

Martin B.I., Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299(6):656-664.

Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium. Management of acute low back pain. Southfield, MI: Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium; 2008. p 1

1. Hegmann K.T. Low back disorders. In: Glass L.S., editor. Occupational medicine practice guidelines:evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers. ed 2. Elk Grove Village, IL: American college of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM); 2007:366.

2. Hart L.G., Deyo R.A., Cherkin D.C. Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:11-19.

3. Andersson G.B. Epidemiologic features of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581-585.

4. Martin B.I., Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299(6):656-664.

5. Buti R. Herniated lumbar discs: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1998;10(12):547-550.

6. Deyo R.A., Weinstein J.N. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;16(2):363-370.

7. Cohen R.I., Chopra P., Upshur C. Low back pain, part 1: primary care work-up of acute and chronic symptoms. Geriatrics. 2001;56(11):26-37.

8. Byrne T.N., Benzel E.C., Waxman S.G. Pain of spinal origin. In: Byrne T.N., Benzel E.C., Waxman S.G., editors. Diseases of the spine and spinal cord. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000:91-123.

9. Goldberg M.S., Scott S.C., Mayo N.E. A review of the association between cigarette smoking and the development of nonspecific back pain and related outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;23(8):995-1014.

10. Leboeuf-Yde C. Smoking and low back pain. Spine. 1999;24(14):1463-1470.

11. Leboeuf-Yde C., Kyvik K.O., Bruun N.H. Low back pain and lifestyle: part I: smoking. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(20):2207-2214.

12. Leboeuf-Yde C., Kyvik K.O., Bruun N.H. Low back pain and lifestyle: part II: obesity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(8):779-784.

13. Rush A.J., Polatin P., Gatchel R.J. Depression and chronic low back pain: establishing priorities in treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2566-2571.

14. Power C., Frank J., Hertzman C., et al. Predictors of low back pain onset in a prospective British study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1671-1678.

15. Linton S.J. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1148-1156.

16. Truchon M. Determinants of chronic disability related to low back pain: towards an integrative biopsychosocial model. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:758-767.

17. Marras W.S., Davis K.G., Heaney C.A., et al. The influence of psychosocial stress, gender and personality on mechanical loading of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(23):3045-3054.

18. Lahad A., Malter A.D., Bert A.O., et al. The effectiveness of four interventions for the prevention of low back pain. JAMA. 1994;272(16):1286-1291.

19. Linton S.J., van Tulder M.W. Preventive interventions for back and neck pain problems: what is the evidence? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(7):778-787.

20. Vogt M.T., Hanscom B., Lauerman W.C. Influence of smoking on the health status of spinal patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:313-319.

21. van Tulder M.W., Koes B.W., Bouter L.M. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(18):2128-2156.

22. van Tulder M.W., Scholten RJPM, Koes B.W., et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(19):2501-2513.

23. Malanga F.A., Nadler S.F. Nonoperative treatment of low back pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:1135-1148.

24. Stauffer J.D. Antidepressants and chronic pain. J Fam Pract. 1987;25(2):167-170.

25. Feinmann C. Pain relief by antidepressants: possible modes of action. Pain. 1985;23(1):1-8.

26. Atkinson J.H., Slater M.A., Wahlgren D.R., et al. Effects of noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants on chronic low back pain intensity. Pain. 1999;83(2):137-145.

27. Pennick V., Sinclair S. What is the optimal evidence-based management of chronic non-specific low-back pain? Linkages: transferring research into practice. August 2002.

28. Nutter P. Aerobic exercise in the treatment and prevention of low back pain. Occup Med. 1988;3(1):137-145.

29. Sculco A.D., Paup D.C., Fernhall B., Sculco M.J. Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J. 2001;1:95-101.

30. Kraus H., Melleby H., Gaston S.R. Back pain correction and prevention. National voluntary organizational approach. NY State J Med. 1977;77:1335-1338.

31. Mayer T.G., Smith S.S., Keeley J., et al. Quantification of lumbar function. Plane trunk strength in chronic low back patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:91-103.

32. Deyo R.A., Walsh N., Martin D., et al. A controlled trial of transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation (TENS) and exercise for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1627-1634.

33. Williams P.C. The lumbosacral spine, emphasizing conservative management. New York: McGraw Hill; 1965.

34. Philadelphia Panel. Philadelphia panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on selected rehabilitation interventions for neck pain.. 2001;81:1701-1717.

35. Davies J.E., Gibson T., Tester L. The value of exercises in the treatment of low back pain. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1979;18:243-247.

36. Gilbert J.R., Taylor D.W., Hildebrand A., et al. Clinical trial of common treatments for low back pain in family practice. Br Med J. 1985;291:7910-7914.

37. Kendall P.H., Jenkins J.M. Exercises for backache: a doubleblind controlled trail. Physiotherapy. 1968;54:154-157.

38. Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium. Management of acute low back pain. Southfield, MI: Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium; 2008. p 1

39. Hultman G., Nordin M., Saraste H., et al. Body composition, endurance, strength, cross section of area and density of erector spiny muscles in men with and without low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:114-123.

40. Shirdo O., Kaneda K., Ito T. Trunk muscle strength during concentric and eccentric contraction: a comparison between healthy subjects and patients with low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:175-182.

41. Deyo R.A., Diehl A.K., Rosenthal M. How many days of bed rest for acute low back pain? A randomized clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(17):1064-1070.

42. Hagen K.B., Hilde G., Jamtvedt G., et al. The Cochrane review of bed rest for acute low back pain and sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2932-2939.

43. Waddell G., Feder G., Lewis M. Systematic reviews of bed rest and advice to stay active for acute low back pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(423):647-652.

44. Muller E.A. Influence of training and inactivity on muscle strength. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1970;51:449-462.

45. Convertino V., Hung J., Goldwater D. Cardiovascular responses to exercise in middle-aged men after 10 days of bed rest. Circulation. 1982;65:134-140.

46. Scott S.C., Goldbert M.S., Mayo N.E., et al. The association between cigarette smoking and back pain in adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1090-1098.

47. Fanuele J.C., Abdu W.A., Hanscom B., et al. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(3):306-312.

48. Benzel E. Exercise, conditioning, and other non-operative strategies. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Biomechanics of spine stabilization. Rolling Meadows, IL: The American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 2001:343-356.

49. Majkowksi G.R., Jovag B.W., Taylor B.T., et al. The effect of back belt use on isometric lifting force and fatigue of the lumbar paraspinal muscles. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2104-2109.

50. Beurskens A.J., de Vet H.C., Koke A.J., et al. Efficacy of traction for nonspecific low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(23):2756-2762.

51. Jette D.U., Jette A.M. Physical therapy and health outcomes in patients with spinal impairments. Phys Ther. 1996;76:930-941.

52. Nadler S.F., Steiner D.J., Erasala G.N., et al. Continuous lowlevel heat wrap therapy provides more efficacy than ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(10):1012-1017.

53. Furlan A.D., Brosseau L., Imamura M., et al. Massage for low-back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(17):1896-1910.

54. Curtis P., Carey T.S., Evans P. Training primary care physicians to give limited manual therapy for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2954-2961.

55. Carlsson C., Sjolund B. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study with longterm follow-up. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(4):296-305.

56. Schmitt H., Zhao J., Brocai D. Acupuncture treatment of low back pain. Schmerz. 2001;15(1):33-37.

57. Collacott E.A., Zimmerman J.T., White D.W. Bipolar permanent magnets of the treatment of chronic low back pain: a pilot study. JAMA. 2000;283(10):1322-1325.

58. Rittweger J., Just K., Kautzsch K. The treatment of chronic lower back pain with lumbar extension and whole-body vibration exercise. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(17):1829-1834.

59. Heary R.F. Intradiscal electrothermal annuloplasty: the IDET procedure. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:353-360.

60. Block A.R., Vanharanta H., Ohnmeiss D.D. Discographic pain report: influence of psychological factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:334-338.

61. Smith S.E., Darden B.V., Rhyne A.L., et al. Outcome of unoperated discogram-positive low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:1997-2000.

62. Carragee E.J., Chen Y., Tanner C.M. Can discography cause long-term back symptoms in previously asymptomatic subjects? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1803-1808.

63. Skouen J.S., Gradal A.L., Haldorsen E., et al. Relative cost-effectiveness of extensive and light multidisciplinary treatment programs versus treatment as usual for patients with chronic low back pain on long-term sick leave. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(9):901-909.