Chapter 81C Noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases

Overview

Hepatic resection is a well-established therapy for patients with liver metastases from colorectal or neuroendocrine carcinoma. Resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer (CRC) results in a 3-year survival rate of 30% to 61% and a 5-year survival rate of 16% to 51%, depending on patient selection (Choti et al, 2002; Fong et al, 1997, 1999; Scheele et al, 1995; Schlag et al, 1990; Tomlinson et al, 2007; see Chapter 81A). In patients with hepatic neuroendocrine metastases, 5-year survival rates of 76% have been achieved with surgical resection, and some surgeons occasionally employ liver transplantation (Chamberlain et al, 2000; Lehnert, 1998; see Chapter 81B). In contrast, the role of hepatectomy in patients with liver metastases from noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine (NCNN) tumors is not well defined, but the number of reports on this topic is increasing.

Series Summarizing Multiple Primary Tumor Types

Most current reports regarding hepatectomy for metastases of NCNN tumors combine multiple primary tumor types in order to have a sufficient number of patients to analyze. Despite this approach, most series are still limited by small numbers or inclusion of patients with neuroendocrine metastases (Benevento et al, 2000; Buell et al, 2000; Elias et al, 1998; Goering et al, 2002; Hamy et al, 2000; Hemming et al, 2000; Karavias et al, 2002; Laurent et al, 2001; Schwartz, 1995; Takada et al, 2001; van Ruth et al, 2001; Yamada et al, 2001).

Goering and colleagues (2002) reported the outcome of 48 patients who had undergone liver resection or ablation for liver metastases from noncolorectal tumors. With a median follow-up of 48 months, the 5-year survival rate was 39%, and the median overall survival was 45 months. No difference was found in survival between patients treated with liver resection versus those treated with cryotherapy. The 3-year survival for patients with primary neuroendocrine (n = 13), genitourinary (n = 16), and soft tissue tumors (n = 15) was 91%, 52%, and 34%, respectively (P = .26).

Elias and colleagues (1998) performed hepatectomy in 147 patients with liver metastases from a noncolorectal primary. Operative mortality was 2%. The overall 5-year survival rate was 36% with the following results for various primary tumors: breast cancer 20% (n = 35), neuroendocrine tumor 74% (n = 27), testicular cancer 46% (n = 20), sarcoma 18% (n = 13), and gastric cancer 20% (n = 11). The authors pointed out that the overall survival was similar to results they obtained in 270 patients who underwent liver resection for metastases of CRC.

Hemming and associates (2000) performed liver resections in 37 patients with NCNN primaries. After a median follow-up of 22 months, the overall 5-year survival rate was 45%. Curative resection and primary tumor type were independent prognostic markers of overall survival in this series. In the subgroup with nongastrointestinal primary tumors (n = 30), the overall 5-year survival rate was 60% compared with 0% for patients with gastrointestinal primary tumors (n = 7; P = .01).

Laurent and coworkers (2001) analyzed the outcome of 39 patients who underwent potentially curative resection of NCNN liver metastases. Patients had primary gastrointestinal (n = 15), genitourinary (n = 12), or miscellaneous (n = 12) tumors. The 5-year survival for the entire group was 35%. Notably, 5-year survival was 100% for patients with a disease-free interval that exceeded 24 months from removal of the primary versus 10% otherwise (P = .01). No other prognostic parameters were identified.

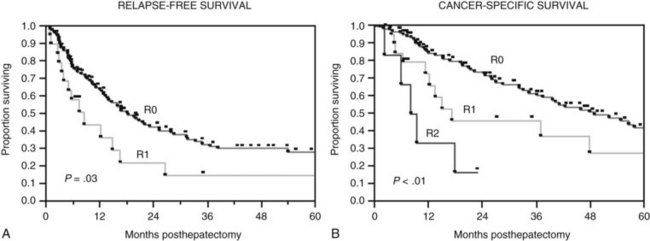

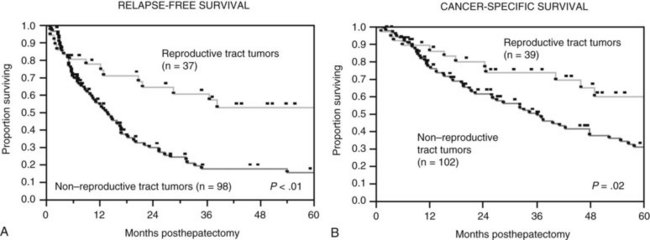

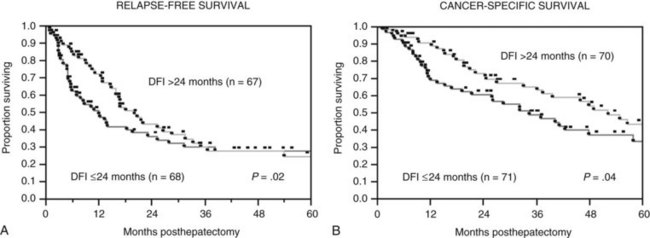

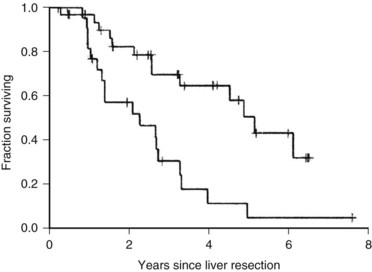

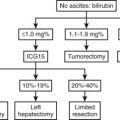

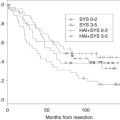

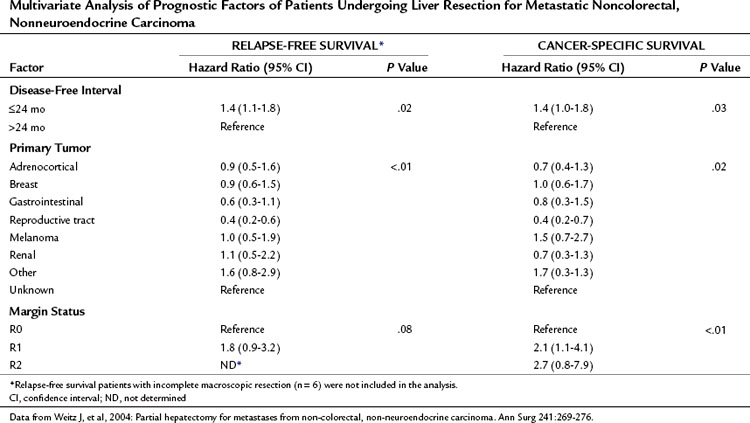

The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) experience of hepatic resection for metastases from NCNN carcinoma was analyzed by Weitz and associates (2004). The objectives of this study were to define perioperative and long-term outcome and to define prognostic factors for survival in 141 patients who underwent resection for liver metastases from NCNN carcinoma during the period from April 1981 through April 2002. Table 81C.1 depicts the primary tumor types. The median operative time was 238 minutes (interquartile range, 180 to 321 minutes), and the median blood loss was 600 mL (interquartile range, 250 to 1420 mL). The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (interquartile range, 7 to 12 days). Of 141 patients, 46 (33%) developed postoperative complications, but the 30-day mortality rate was 0%. The median follow-up was 26 months, with a median follow-up of 35 months. The 3-year relapse-free survival rate was 30% (median, 17 months), and the 3-year cancer-specific survival rate was 57% (median, 42 months). Primary tumor type and length of disease-free interval from the primary tumor were significant independent prognostic factors for relapse-free and cancer-specific survival (Figs. 81C.1 to 81C.3; Table 81C.2).

Table 81C.1 Primary Tumor Type of Patients Undergoing Liver Resection for Metastatic Noncolorectal, Nonneuroendocrine Tumors

| Primary Tumor | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Breast | 29 (20) |

| Melanoma | 17 (12) |

| Reproductive tract | 39 (28) |

| Testicular | 20 (14) |

| Gynecologic | 19 (14) |

| Ovarian | 12 |

| Endometrial | 4 |

| Cervical | 2 |

| Fallopian tube | 1 |

| Adrenocortical | 15 (11) |

| Renal | 11 (8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 (9) |

| Stomach | 3 |

| Duodenal | 1 |

| Pancreatic | 5 |

| Ampullary | 2 |

| Anal | 1 |

| Other | 13 (9) |

| Lung | 4 |

| Salivary gland | 3 |

| Nasopharyngeal | 2 |

| Glottal | 1 |

| Tonsil | 1 |

| Thyroid | 1 |

| Sweat gland | 1 |

| Unknown | 5 (3) |

Data from Weitz J, et al, 2004: Partial hepatectomy for metastases from non-colorectal, nonneuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann Surg 241:269-276.

Table 81C.2 Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors of Patients Undergoing Liver Resection for Metastatic Noncolorectal, Nonneuroendocrine Carcinoma

Laparoscopy might be a reasonable staging tool for patients with NCNN liver metastases. D’Angelica and coworkers (2002) examined 30 patients with potentially resectable NCNN tumors based on preoperative imaging. Nine of these patients had unresectable disease, six of whom were identified by laparoscopy.

Adam and colleagues (2006) reported the results of 1452 patients undergoing hepatic resection for NCNN liver metastases. The primary tumors were most commonly located in the breast (32%) and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (16%) or were urologic tumors (14%). Operative mortality rate was 2.3%, with a surgical morbidity of 21.5%. Overall 5- and 10-year survival rates were 36% and 23%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, patient age (>60 years), type of primary tumor (non-breast, melanoma, or squamous cell histology), extrahepatic disease, R2 resection, and major hepatectomy were independent adverse prognostic factors. Using these factors, patients could be classified into low risk (0 to 3 risk factors, 5-year survival: 46%), medium risk (4 to 6 risk factors, 5-year survival: 33%), and high risk (>6 risk factors, 5-year survival: <10%; P = .0001).

Series Focused on One Primary Tumor Type

Sarcoma

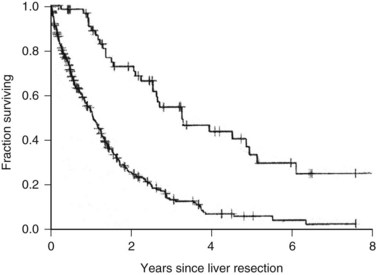

One of the largest surgical series of patients with sarcoma metastatic to the liver was composed of 56 patients who underwent liver resection (DeMatteo et al, 2001). These patients were selected from 331 patients with liver metastases from sarcomas who had been admitted to MSKCC during the years 1982 through 2000. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs; Fig. 81C.4) and leiomyosarcomas were the most common histology; no perioperative deaths were reported in patients undergoing complete resection of the tumor, and the 5-year overall survival rate was 30% with a median of 39 months in completely resected patients. Patients who did not undergo complete resection had a 5-year survival of only 4% (Fig. 81C.5). A disease-free interval of less than 24 months was a significant adverse prognostic parameter for survival on univariate and multivariate analysis (Fig. 81C.6).

In a report from Pawlik and colleagues (2006b), 66 patients undergoing liver resection and/or ablation were included; the 5-year disease-free and overall survival rates were 16.4% and 27.1%, respectively. Patients in whom RFA was part of the treatment and patients who did not receive chemotherapy, mostly imatinib mesylate for metastatic GISTs, showed a significantly reduced survival.

The treatment strategy for patients with liver metastases from GISTs has changed since the development of the targeted agent imatinib mesylate, which achieves dramatic tumor response rates (Corless et al, 2004; DeMatteo, 2002) such that imatinib is now the first-line treatment. Resection is considered for patients when they reach the maximal response to imatinib, if all gross tumor can be removed and for those who have immediate or limited acquired resistance to the drug (Antonescu et al, 2005). Patients with mulitfocal resistance to imatinib seem not to beneftit from surgical intervention (DeMatteo et al, 2007).

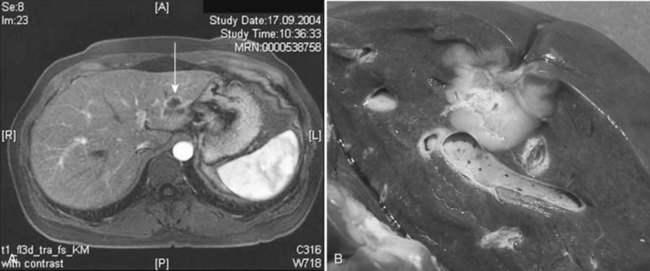

Breast Cancer

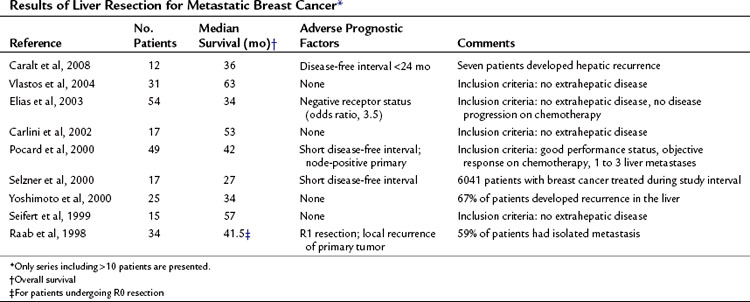

In a small proportion (4% to 5%) of patients with breast cancer, liver metastases are the only sign of disseminated disease (Fig. 81C.7; Elias et al, 2003). Although it has not been formally proven that liver resection prolongs survival for selected patients with liver metastases of breast cancer, 5-year survival was 33% to 61% in more recently published series (Caralt et al, 2008; Elias et al, 2003; Vlastos et al, 2004). Patients with liver metastases from breast cancer receiving chemotherapy only rarely, if ever, survive 5 years (Wyld et al, 2003). Even with aggressive systemic chemotherapy, the median survival for patients with isolated liver metastases of breast cancer was only 23 to 27 months, with time to progression of 8 to 10 months in two more recent trials (Atalay et al, 2003). Resection for liver metastases in this setting may prolong survival for a subset of highly selected patients (Singletary et al, 2003).

Table 81C.3 summarizes the published studies of liver resection for metastatic breast cancer. Meaningful comparisons between these studies cannot be made, because they are heterogeneous studies reporting small patient numbers with different inclusion criteria and treatment strategies. Valid criteria for selecting patients who might benefit from hepatic resection for metastases of breast cancer cannot be defined at this time. A common recommendation is that patients with extrahepatic disease should not undergo liver resection, even though some studies did not find a worse prognosis for such patients. Some authors also suggest that patients should first undergo systemic chemotherapy, and that only patients who do not progress should undergo liver resection. Formal randomized trials confirming this strategy have not been performed. Recently, a report regarding radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been published; median survival for included patients was 30 months, but the follow-up time was only 19 months, and the local tumor progression rate was 25% (Meloni et al, 2009).

Melanoma

Melanoma recurs after potentially curative resection in approximately one third of patients, with almost every organ being at risk (Allen & Coit, 2002). Hepatic metastases are diagnosed in about 10% to 20% of patients with stage IV melanoma, even though it is well documented that most patients have liver metastases on postmortem examination. Patients with liver metastases as the initial site of metastatic disease have a very poor prognosis, with a median survival of 4.4 months (Rose et al, 2001). Most patients have unresectable disease, owing to extrahepatic disease or disseminated hepatic metastases. This point was shown by a study from the John Wayne Cancer Institute and the Sydney Melanoma Unit (Rose et al, 2001). During the years 1971 through 1999, 26,204 patients with melanoma were seen in these institutions, and 1750 patients (6.7%) had liver metastases. Only 34 patients underwent surgical exploration for attempted liver resection, and hepatectomy was performed in 24 patients. Of these 24 patients, 12 had synchronous extrahepatic disease, and 18 patients could be rendered disease free surgically. The 10 patients who underwent exploration only had a median survival of 4 months; the overall survival of all patients with liver metastases treated nonoperatively was 6 months. Overall survival in the patients who underwent complete resection was 28 months, with a median disease-free survival of 12 months. One patient achieved 10-year survival, and the 5-year overall survival was 29%. Complete gross resection and histologically negative margins were associated with an improved disease-free survival, and complete gross resection showed a trend for improved overall survival (P = .06).

From this experience, one might conclude that extrahepatic disease per se is not a contraindication for resection, as long as all disease is resectable. Selection of patients is crucial, which is well documented in this study. Only 1.4% of all patients with liver metastases underwent hepatic resection, and these patients had a median disease-free interval of 58 months before presenting with hepatic metastases. Several other small series in the literature mostly comprise fewer than 10 patients undergoing liver resection for metastatic melanoma, with median survival times of 10 to 51 months (Herman et al, 2007; Rose et al, 2001). Repeat hepatic resection might be beneficial for some patients who can be rendered disease-free surgically (Mondragon-Sanches et al, 1999).

Uveal Melanoma

Uveal melanoma is a distinct entity that seems to have a different tumor biology, and it commonly spreads to the liver. About 50% to 80% of patients with uveal melanoma who develop distant metastases have liver involvement. Hsueh and colleagues (2004) reported 112 patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, and 78 patients had liver metastases. A total of 24 patients underwent surgical resection for metastatic disease, five with liver metastases. A multivariate analysis showed resection, but not site of metastasis, to be a significant predictor of survival. The median survival for patients undergoing resection was 38 months in this series, with a 5-year survival of 39%. Aoyama and colleagues (2000) presented a series of 12 patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, nine with liver metastases. Median recurrence-free survival after complete resection was 19 months, with a median overall survival exceeding 27 months, emphasizing that selected patients with metastatic melanoma may benefit from resection. In a report from Pawlik and colleagues (2006a), 16 patients with liver metastases from ocular melanoma underwent resection; the median time to recurrence was 8.8 months. Compared with patients undergoing liver resection for metastatic cutaneous melanoma, more patients developed recurrent disease in the liver (53% vs. 17%); however, the 5-year survival was significantly better for metastatic ocular melanoma (21% vs. 0%; P = .015). Despite these data, most patients with liver metastases from uveal melanoma are not candidates for a complete resection. For these patients, regional chemotherapy might offer increased response rates, and probably increased overall survival, compared with other treatment options (Feldman et al, 2004).

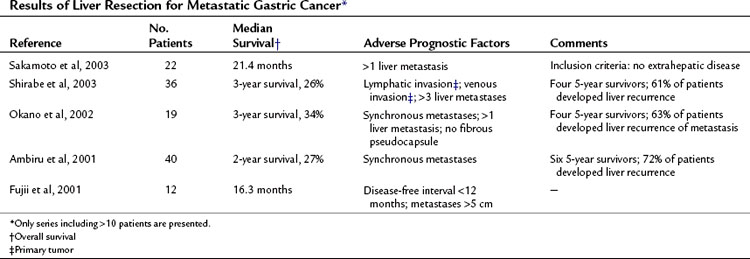

Gastric and Pancreatic Cancer

Most reports on liver resection for NCNN metastases of gastrointestinal origin are based on patients with gastric cancer. Patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic gastric cancer are highly selected, which is apparent in the report of Ochiai and colleagues (1994), who treated 6540 patients with gastric cancer. Liver resection for metastases was performed in only 30 of these patients (0.46%). Table 81C.4 summarizes more recently published data; there have been few long-term survivors.

Only a handful of long-term survivors have been reported after the resection of liver metastases from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Detry et al, 2003). In a report from Shrikhande and colleagues (2007), 11 patients underwent combined pancreatic and liver resection for metastatic pancreatic cancer, with a median survival of 11.4 months. A recent review on this topic summarized 103 patients who underwent liver resection for metastastic pancreatic cancer; median survival ranged from 5.8 to 11.3 months (Michalski et al, 2008). Consequently, surgery remains highly controversial and unlikely to benefit most of these patients. For other primary malignant tumors of the pancreas that show a less aggressive tumor biology, such as solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas, resection of liver metastases might be justified (Martin et al, 2002).

Renal Carcinoma

About 10% of patients with renal tumors develop liver metastases, and they have a dismal prognosis: fewer than 10% survive beyond 1 year, and only about 2% to 4% develop hepatic disease that is amenable to complete resection. Several series in the literature report fewer than 10 patients undergoing liver resection for metastatic renal tumors, with survival exceeding 5 years in about 13% of patients (Alves et al, 2003). In one series, 14 patients with liver metastases from primary renal tumors underwent partial hepatectomy (Alves et al, 2003). Median survival was 26 months, with a 3-year survival of 26%. Patients with a disease-free interval less than 24 months and patients with a diameter of the metastases exceeding 5 cm showed a worse prognosis. In patients with recurrence after hepatic resection, survival was better for patients who could undergo a repeat hepatectomy. In a more recent report on 31 patients, 5-year overall survival was 39% for the whole patient group and 50% for margin-negative patients (Thelen et al, 2007). In patients with hepatic metastases from renal tumors who are candidates for a complete resection, surgical exploration may be justified. Other therapies should also be considered, such as hepatic artery embolization and targeted molecular therapy, such as with sunitinib.

Reproductive Tract Tumors

Effective chemotherapeutic regimens are available for most reproductive tumors. Resection is only one component of a multimodal approach to the treatment of liver metastases from these tumors. The development of liver metastases is a well-defined adverse prognostic factor for patients with germ cell tumors (Gholam et al, 2003). Rivoire and associates (2001) attempted to define guidelines for the resection of liver metastases from germ cell tumors. These authors examined 37 patients who had undergone liver resection for metastatic germ cell tumors. All patients had received cisplatin-based chemotherapy before surgery. Median survival was 54 months with an overall 5-year survival rate of 62%. The authors defined three prognostic factors associated with a worse outcome: 1) pure embryonal carcinoma in the primary tumor, 2) liver metastasis greater than 3 cm, and 3) presence of viable residual disease after chemotherapy. Because no patient with liver tumors less than 1 cm had viable disease, the authors recommended a nonsurgical approach for these patients. Men with liver tumors greater than 3 cm in diameter represent a high-risk group that may not benefit from partial hepatectomy, but resection was recommended for the other subgroups.

Hahn and coworkers (1999) presented data regarding 57 patients undergoing liver resection for metastatic testicular cancer after systemic chemotherapy. In 48 patients, concomitant cytoreductive procedures for extrahepatic disease were performed. The overall 2-year survival rate was 97.1%. Pathologic analysis of resected specimens showed either a benign lesion or only necrotic tumor in 58% of specimens. Three of five patients with active disease and persistently elevated serum markers died during follow-up, underlining the importance of response to chemotherapy as a predictor of outcome.

Patients with metastatic ovarian or fallopian tube carcinoma usually do not present with isolated liver metastases, because the disease is generally diffuse within the abdomen and pelvis. Cytoreductive surgery that reduces disease to less than 1 cm when combined with chemotherapy is an accepted treatment approach. For these diseases, liver resection may be necessary because of true liver metastases or secondary liver involvement by peritoneal disease. A median overall survival of 62 months after hepatic resection has been described with this approach in 24 patients, with 18 patients having extrahepatic disease at the time of hepatectomy (Yoon et al, 2003). In this study, complete resection of all gross disease was possible in 21 patients, whereas in three patients, tumor debulking to less than 1 cm was performed. Merideth and colleagues (2003) reported 26 patients who underwent liver resection for metachronous metastases from ovarian carcinoma; cytoreduction was suboptimal (residual tumor = 1 cm) in five patients. Median disease-related survival was 26.3 months, and a disease-free interval exceeding 12 months and optimal cytoreduction were associated with improved outcome. Other reports also justify hepatic resection in metastatic ovarian carcinoma (Bristow et al, 1999; Chi et al, 1997; Lim et al, 2009). Unlike most other tumors, ovarian cancer is usually confined to the liver surface, and although extensive involvement can be seen, intraparenchymal hepatic metastases are uncommon (Fig. 81C.8).

Liver resection for metastases from cervical and endometrial cancer have been reported in the literature with an overall survival of 7 to 50 months (Kollmar et al, 2008; Tangjitgamol et al, 2004). Selected patients may benefit from hepatectomy; however, because of the small number of published cases, no general conclusions can be drawn from the available data.

Other Primary Tumors

Resection of liver metastases of lung cancer has been reported, and in selected patients, long-term survival has been achieved. Di Carlo and associates (2003) summarized the available data from the literature. Liver resection was performed in 14 patients with liver metastases from lung cancer, and two patients lived longer than 5 years.

A recent report summarized the results of hepatic resection for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from various primary sites (anus, head/neck, lung, esophagus, and others) (Pawlik et al, 2007). The median overall survival was 22 months, with synchronous disease, metastasis size greater than 5 cm, and positive surgical margins being adverse prognostic parameters.

Patients presenting with liver metastases from an unknown primary tumor are a challenge to manage, because median overall survival is approximately 5 months. Liver resection or ablative therapy might be appropriate for some patients, in whom all disease can be destroyed or removed, but a median disease-free survival of only 6.5 months has been reported (Hawksworth et al, 2004).

Critical Evaluation of Liver Resection for Metastatic Noncolorectal Nonneuroendocrine Tumors

Two different concepts explain the relatively favorable outcome of patients undergoing hepatectomy for liver metastases from CRC: First, the tumor biology of metastatic CRC may be different from that of other solid tumors. Tumor cell dissemination of CRC via the bloodstream may be inefficient and could lead to death of most of the tumor cells shed into the bloodstream before the development of clinically significant metastases. Implantation of circulating colorectal tumor cells in the liver may be particularly effective owing to the expression of particular adhesion molecules (Mizuno et al, 1998; Sugarbaker, 1993; Weiss, 1990). The second reason may be the venous drainage of the large intestine via the portal vein to the liver. Tumor cells that reach the liver through the portal vein may be effectively entrapped by the liver, preventing systemic spread. If this concept is correct, tumor cells must overcome hepatic filtration to reach the systemic circulation and cause distant metastases (Sugarbaker, 1993).

Both notions are substantiated by clinical and experimental findings. It could be shown that the liver is an effective filter for CRC cells, because these cells can be found more frequently in blood samples obtained from the portal vein compared with blood samples from the vena cava (Koch et al, 2001). Tumor biology is also important, however, because the most relevant prognostic factors after resection of colorectal liver metastases, such as length of disease-free interval and nodal status of primary tumor, are at least in part surrogates for tumor biology (Fong et al, 1999).

Adam R, et al. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2006;255:524-535.

Allen P, Coit DG. The surgical management of metastatic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:762-770.

Alves A, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic renal tumors: is it worthwhile? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:705-710.

Ambiru S, et al. Benefits and limits of hepatic resection for gastric metastases. Am J Surg. 2001;181:279-283.

Antonescu CR, et al. Acquired resistance to imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor occurs through secondary gene mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4182-4190.

Aoyama T, et al. Protracted survival after resection of metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1561-1568.

Atalay G, et al. Clinical outcome of breast cancer patients with liver metastases alone in the anthracycline-taxane era: a retrospective analysis of two prospective, randomised metastatic breast cancer trials. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2439-2449.

Benevento A, et al. Results of liver resection as treatment for metastases from noncolorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:24-29.

Bristow RE, et al. Survival impact of surgical cytoreduction in stage IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:278-287.

Buell JF, et al. Hepatic resection: effective treatment for primary and secondary tumors. Surgery. 2000;128:686-693.

Caralt M, et al. Hepatic resection for liver metastases as part of the “oncosurgical” treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2804-2810.

Carlini M, et al. Liver metastases from breast cancer: results of surgical resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1597-1601.

Chamberlain RS, et al. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432-445.

Chi DS, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic gynecologic carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:45-51.

Choti MA, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235:759-766.

Corless CL, et al. Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3813-3825.

D’Angelica M, et al. Staging laparoscopy for potentially resectable noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:204-209.

DeMatteo RP. The GIST of targeted cancer therapy: a tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor), a mutated gene (c-kit), and a molecular inhibitor (STI571). Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:831-839.

DeMatteo RP, et al. Results of hepatic resection for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Ann Surg. 2001;234:540-548.

DeMatteo RP, et al. Results of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy followed by surgical resection for metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Surg. 2007;245:347-352.

Detry O, et al. Liver resection for noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine metastases. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:458-462.

Di Carlo I, et al. Liver metastases from lung cancer: is surgical resection justified? Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:291-293.

Elias D, et al. Resection of liver metastases from a noncolorectal primary: indications and results based on 147 monocentric patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:493.

Elias D, et al. An attempt to clarify indications for hepatectomy for liver metastases from breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2003;185:158-164.

Feldman ED, et al. Regional treatment options for patients with ocular melanoma metastatic to the liver. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:290-297.

Fong Y, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:938-946.

Fong Y, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309-318.

Fujii K, et al. Resection of liver metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;45:368-371.

Gholam D, et al. Advanced seminoma-treatment results and prognostic factors for survival after first-line, cisplatin-based chemotherapy and for patients with recurrent disease: a single-institution experience in 145 patients. Cancer. 2003;98:745-752.

Goering JD, et al. Cryoablation and liver resection for noncolorectal liver metastases. Am J Surg. 2002;183:384-389.

Hahn TL, et al. Hepatic resection of metastatic testicular carcinoma: a further update. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:640-644.

Hamy AP, et al. Hepatic resections for non-colorectal metastases: forty resections in 35 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1090-1094.

Hawksworth J, et al. Surgical and ablative treatment for metastatic adenocarcinoma to the liver from unknown primary tumor. Am Surg. 2004;70:512-517.

Hemming AW, et al. Hepatic resection of noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:97-101.

Herman P, et al. Selected patients with metastatic melanoma may benefit from liver resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:171-174.

Hsueh EC, et al. Prolonged survival after complete resection of metastases from intraocular melanoma. Cancer. 2004;100:122-129.

Karavias DD, et al. Liver resection for metastatic non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine hepatic neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:135-139.

Koch M, et al. Comparative analysis of tumor cell dissemination in mesenteric, central and peripheral venous blood in patients with colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;136:85-89.

Kollmar O, et al. Surgery of liver metastasis in gynecological cancer: indication and results. Onkologie. 2008;31:375-379.

Laurent C, et al. Resection of noncolorectal and nonneuroendocrine liver metastases: late metastases are the only chance of cure. World J Surg. 2001;25:1532-1536.

Lehnert T. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: an analysis of 103 patients. Transplantation. 1998;66:1307-1312.

Lim MC, et al. The clinical significance of hepatic parenchymal metastasis in patients with primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:28-34.

Martin R, et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a surgical enigma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:35-40.

Meloni MF, et al. Breast cancer liver metastases: US-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation—intermediate and long-term survival rates. Radiology. 2009;253:861-869.

Merideth MA, et al. Hepatic resection for metachronous metastases from ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:16-21.

Michalski CW, et al. Resection of pirmary pancreatic cancer and liver metastases: a systematic review. Dig Surg. 2008;25:473-480.

Mizuno N, et al. Importance of hepatic first-pass removal in metastasis of colon carcinoma cells. J Hepatol. 1998;28:865-877.

Mondragon-Sanches R, et al. Repeat hepatic resection for recurrent metastatic melanoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:459-461.

Ochiai T, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumours from gastric cancer: analysis of prognostic factors. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1175-1178.

Okano K, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumors from gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;235:86-91.

Pawlik T, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic melanoma: distinct patterns of recurrence and prognosis for ocular versus cutaneous disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:712-720.

Pawlik T, et al. Results of a single-center experience with resection and ablation for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Arch Surg. 2006;141:537-544.

Pawlik T, et al. Liver-directed surgery for metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to the liver: results of a mulit-center analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2807-2816.

Pocard M, et al. Hepatic resection in metastatic breast cancer: results and prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:155-159.

Raab R, et al. Liver metastases of breast cancer: results of liver resection. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2231-2233.

Rivoire M, et al. Multimodality treatment of patients with liver metastases from germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2001;92:578-587.

Rose DM, et al. Surgical resection for metastatic melanoma to the liver: the John Wayne Cancer Institute and Sydney Melanoma Unit experience. Arch Surg. 2001;136:950-955.

Sakamoto Y, et al. Surgical resection of liver metastases of gastric cancer: an analysis of a 17-year experience with 22 patients. Surgery. 2003;133:507-511.

Scheele J, et al. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59-71.

Schlag P, et al. Resection of liver metastases in colorectal cancer: competitive analysis of treatment results in synchronous versus metachronous metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1990;16:360-365.

Schwartz SI. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:72-75.

Seifert JK, et al. Liver resection for breast cancer metastases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2935-2940.

Selzner M, et al. Liver metastases from breast cancer: long-term survival after curative resection. Surgery. 2000;127:383-389.

Shrikhande SV, et al. Pancreatic resection for M1 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:118-127.

Shirabe K, et al. Analysis of the prognostic factors of liver metastasis of gastric cancer after hepatic resection: a multi-institutional study of the indications for resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1560-1563.

Singletary E, et al. A role of curative surgery in the treatment of selected patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:241-251.

Sugarbaker PH. Metastatic inefficiency: the scientific basis for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1993;3(Suppl):158-160.

Takada Y, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumors from noncolorectal carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:83-86.

Tangjitgamol S, et al. Role of surgical resection for lung, liver, and central nervous system metastases in patients with gynecological cancer: a literature review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:399-422.

Thelen A, et al. Liver resection for metastases from renal cell carcinoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:802-807.

Tomlinson JS, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4575-4580.

van Ruth S, et al. Metastasectomy for liver metastases of non-colorectal primaries. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:662-667.

Vlastos G, et al. Long-term survival after an aggressive surgical approach in patients with breast cancer hepatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:869-874.

Weiss L. Metastatic inefficiency. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;54:159-211.

Weitz J, et al. Partial hepatectomy for metastases from non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;241:269-276.

Wyld L, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with hepatic metastases from breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:284-290.

Yamada H, et al. Hepatectomy for metastases from non-colorectal and non-neuroendocrine tumor. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:4159-4162.

Yoon SS, et al. Resection of recurrent ovarian or fallopian tube carcinoma involving the liver. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:383-388.

Yoshimoto M, et al. Surgical treatment of hepatic metastases from breast cancer. Br Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:177-184.