21

Neutrophilic Dermatoses

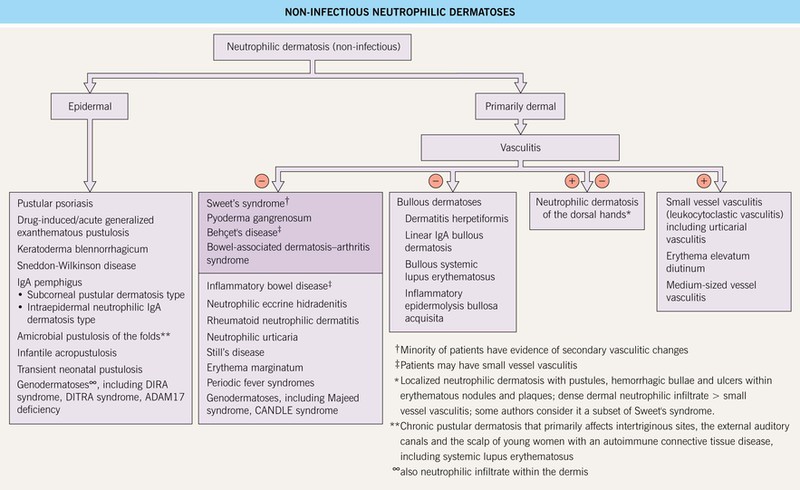

This group of disorders, in an untreated state, is characterized by infiltrates of neutrophils within the skin. In addition, these dermatoses lack an identifiable infectious etiology, despite the presence of neutrophils (Fig. 21.1). There can be significant overlap in the clinical presentations of the neutrophilic dermatoses; for example, in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia, bullous pyoderma gangrenosum may be difficult to distinguish from Sweet’s syndrome. In addition, infiltrates of neutrophils can occur in other organs, particularly the joints, eyes, lungs, and bones. Bone involvement raises the possibility of SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome.

Fig. 21.1 Non-infectious neutrophilic dermatoses. Entities in the darker box are discussed in this chapter. CANDLE, chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature; DIRA, deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; DITRA, deficiency of the IL-36R antagonist.

Sweet’s Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

• Acute onset of erythematous edematous papules and plaques that are tender, but not pruritic; if the edema is intense, the lesions may become bullous and, occasionally, they resemble erysipelas; favored sites are the face, neck, upper trunk, and upper extremities (Fig. 21.2).

Fig. 21.2 Spectrum of cutaneous findings in Sweet’s syndrome. A Edematous erythematous papules and plaques on the neck of a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia. B Markedly edematous plaques on the upper back, some of which are pseudovesicular while others are becoming bullous. C Some of the edematous lesions have a targetoid appearance. D Central hemorrhagic crusts within facial plaques. B, D, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, Courtesy, Mark Davis, MD.

• Less commonly, nodules develop due to neutrophilic panniculitis or pustules form within the plaques; a variant occurs on the dorsal aspect of the hands and is referred to as ‘neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands’ (Fig. 21.3).

Fig. 21.3 Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. This entity has overlapping clinical and histologic features with both Sweet’s syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum. Some patients have an associated pustular vasculitis. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

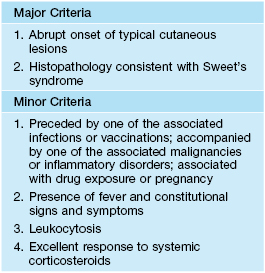

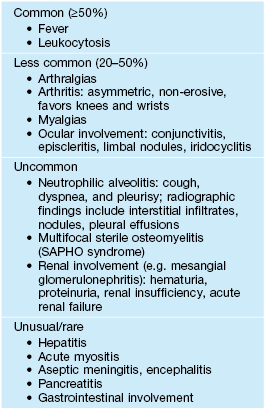

• Associated systemic findings include fever, malaise, and arthralgias, and a peripheral leukocytosis is commonly observed (Table 21.1); some patients also develop systemic manifestations, including ocular, pulmonary, and skeletal involvement (Fig. 21.4, Table 21.2).

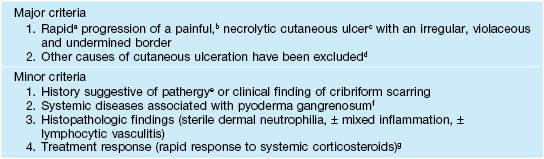

Table 21.1

Criteria for the diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome.

Both of the major criteria and two of the minor criteria are needed for the diagnosis.

From Su WPD, Liu HNH. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis 1986;37:167–174.

Fig. 21.4 Ocular involvement in Sweet’s syndrome. Erythema and hemorrhage of the sclera and conjunctiva. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Table 21.2

Systemic manifestations of Sweet’s syndrome.

SAPHO, synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis.

• DDx: bullous pyoderma gangrenosum, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, erysipelas, erythema multiforme, causes of pseudocellulitis (see Table 61.2), infectious cellulitis, vasculitis (urticarial, small vessel, septic), halogenoderma, periodic fever syndromes, as well as additional entities in Fig. 21.1.

• Rx: usually spontaneously resolves over a few months, but may recur in up to 30% to 50% of patients with idiopathic versus malignancy-associated disease, respectively; antimicrobials for any underlying infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis; for moderate to severe disease, systemic CS (e.g. prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day tapered over several months), dapsone, potassium iodide; for milder disease, ultrapotent topical CS and NSAIDs.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG)

• The most common presentation is a painful, rapidly enlarging ulcer of the lower extremity with a gray-violet, undermined, necrotic border; there is often a peripheral rim of erythema, and the base of the ulcer may be purulent (Fig. 21.5).

Fig. 21.5 Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum. A The edge of this ulceration on the shin is undermined with a violet–gray color as well as an inflammatory rim. Note the central scarring. B In addition to an overhanging border, this deep ulceration on the elbow has a purulent base. A, Courtesy, Mark Davis, MD.

• Ulcers can occur at other sites, including the face, upper extremities, and trunk, as well as peristomally (Fig. 21.6); once partially treated, the ulcer may lose some of its characteristic features.

Fig. 21.6 Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) and underlying disorders – ulcerative colitis and PAPA syndrome. A Multiple ulcers surround an ileostomy (following a total proctocolectomy) in a patient with refractory chronic ulcerative colitis. Although peristomal PG occurs most commonly following intestinal resection of inflammatory bowel disease, it can also follow resection of gastrointestinal or bladder carcinoma. B Bullous PG in a patient with ulcerative colitis. C PG in a patient with PAPA syndrome (pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne). A, Courtesy, Mark Davis, MD; C, Courtesy, Maria Chanco Turner, MD.

• Lesions can begin as an inflammatory papulopustule (which may be follicular), as a bulla on a violaceous base, or at the site of trauma (pathergy) (Fig. 21.7); in some patients, especially those with underlying inflammatory bowel disease and/or arthritis, the ulcers may expand more slowly with significant granulation tissue in their bases; healing of PG ulcers often leads to a distinctive cribriform pattern of scarring.

Fig. 21.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) – early lesion and demonstration of pathergy. A The earliest clinical lesion is a pustule with an inflammatory base; this patient had Crohn’s disease. B Pathergy with an early lesion at the site of an intravenous catheter. C Postsurgical PG following a breast reduction; multiple debridements had been performed and systemic antibiotics administered because the original diagnosis was soft tissue infection. B, Courtesy, Samuel L. Moschella, MD; C, Courtesy, Mark Davis, MD.

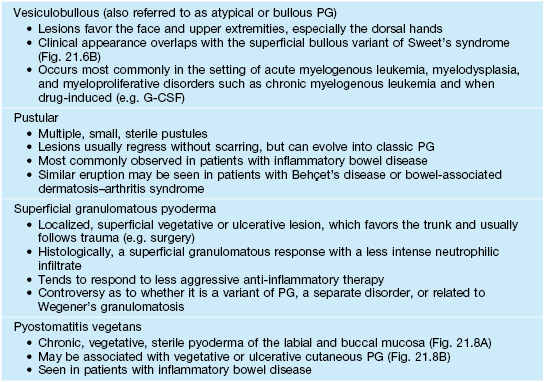

• There are several clinical variants of PG and they are outlined in Table 21.3; the diagnosis of PG requires clinicopathologic correlation and exclusion of other entities in the DDx (Tables 21.4 and 21.5).

Table 21.3

Clinical variants of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG).

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor.

Fig. 21.8 Pyostomatitis vegetans and vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). A Suppurative pyostomatitis vegetans in a patient with ulcerative colitis. B Vegetative form of PG following trauma to the skin. Courtesy, Samuel L. Moschella, MD.

Table 21.4

Proposed diagnostic criteria for classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum.

Diagnosis requires both of the major criteria and at least two minor criteria.

a Characteristic margin expansion of 1–2 cm per day, or a 50% increase in ulcer size within 1 month.

b Pain is usually out of proportion to the size of the ulceration.

c Typically preceded by a papule, pustule, or bulla.

d Usually necessitates skin biopsy and additional evaluation (see Table 21.5) to exclude other causes.

e Ulcer development at sites of minor cutaneous trauma.

f Inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, IgA gammopathy, or underlying malignancy.

g Generally responds to prednisone (1–2 mg/kg/day) or another corticosteroid at an equivalent dosage, with a 50% decrease in size within 1 month.

From Su WP, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: Clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004;43:790–800.

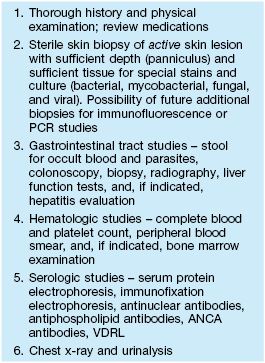

Table 21.5

Evaluation of a patient with presumed pyoderma gangrenosum.

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

• Although idiopathic in up to 50% of patients, the age distribution of PG tends to reflect the major underlying disorders, which are: (1) inflammatory bowel disease, either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease (20–30% of patients); (2) inflammatory arthritis, including rheumatoid and seronegative (20%); (3) plasma cell dyscrasias, particularly an IgA monoclonal gammopathy (up to 15%); and (4) other hematologic malignancies, particularly AML, as well as myelodysplasia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and hairy cell leukemia; the underlying disorder may be antecedent, coincident, or subsequent.

• PG is included in a few rare syndromes that have various combinations of sterile arthritis, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa – e.g. PAPA (pyogenic sterile arthritis, PG and acne; Fig. 21.6C), PASH (PG, acne, suppurative hidradenitis), and PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, suppurative hidradenitis) syndromes.

• DDx for classic ulcerative PG: in the untreated state, it consists primarily of infectious etiologies and vasculitis, but in a partially treated state (usually with oral CS), it includes a host of other causes of ulcers, from venous ulcers to lymphoma and SCC to drug-induced (see Fig. 86.1).

Behçet’s Disease

• A multisystem disease (Table 21.6) whose mucocutaneous features include aphthous orogenital ulcers (Fig. 21.9), sterile pustules (occasionally follicular), and palpable purpura due to small vessel vasculitis, as well as superficial thrombophlebitis and erythema nodosum-like lesions.

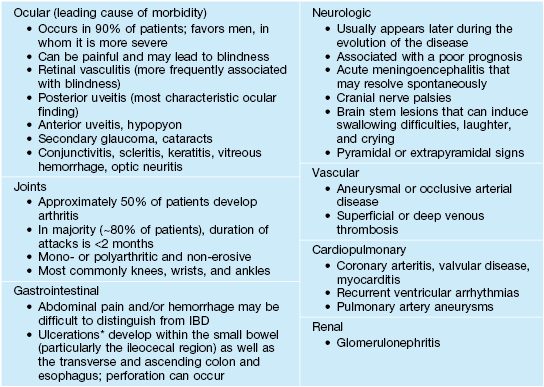

Table 21.6

Systemic manifestations of Behçet’s disease.

* Resemble anogenital aphthae.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Fig. 21.9 Oral and genital ulcers of Behçet’s disease. A Aphthous stomatitis in the form of major aphthae, which are deeper and larger than minor aphthae but share the presence of a pseudomembrane and associated pain. Oral aphthosis is often the initial symptom of Behçet’s disease and may flare with the onset of other symptoms. B Perianal aphthosis. In men, lesions often occur on the scrotum and penis. Courtesy, Samuel L. Moschella, MD.

• Because the diagnosis is made clinically, there are several sets of criteria, including the ones outlined in Table 21.7; there are countries in which the disease is more commonly seen, e.g. Turkey, Japan, and those along the ancient Silk Road; the peak incidence is ages 20–35 years.

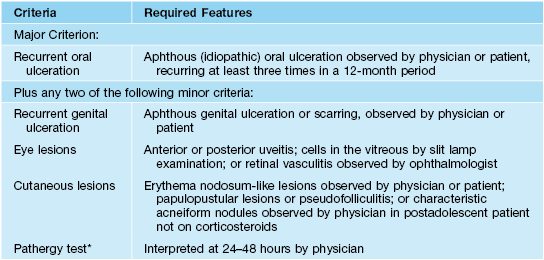

Table 21.7

International study group criteria for the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease.

* Pathergy test is performed on the flexor forearm by obliquely inserting a 20- to 22-gauge sterile hypodermic needle to a depth of 5 mm ± an intradermal injection of 0.1 ml of normal saline. A positive reaction is defined as the development of a papule or pustule.

From International Study Group for Behçet’s disease. Criteria for the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990;335:1078–1080.

• DDx: recurrent genital and oral HSV (the latter is limited to keratinized mucosa in immunocompetent hosts; see Chapter 59), complex aphthosis, inflammatory bowel disease, SLE, pemphigus vulgaris, Marshall’s syndrome (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis).

Bowel-Associated Dermatosis–Arthritis Syndrome (Bowel Bypass Syndrome)

Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis, and Osteitis (SAPHO) Syndrome

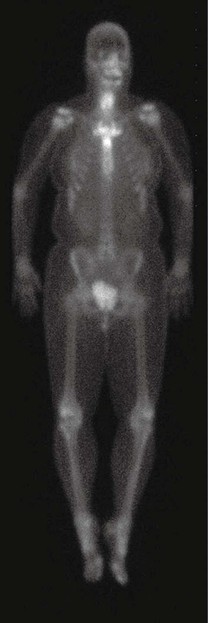

• Characterized by aseptic neutrophilic dermatoses plus aseptic osteoarticular involvement, which is also referred to as chronic recurrent multifocal (aseptic) osteomyelitis; the latter favors the anterior chest and axial skeleton (Fig. 21.10).

Fig. 21.10 Abnormal bone scan in a patient with SAPHO syndrome. There is abnormal tracer uptake within the mid and lower cervical spine and multiple thoracic vertebral bodies (T3 to T9) in addition to the manubrium and sternoclavicular joints. The pattern and anatomic distribution are indicative of increased osteoblastic activity as in the SAPHO syndrome. Courtesy, Samuel L. Moschella, MD.

For further information see Ch. 26. From Dermatology, Third Edition.