Neurology

Neurologic Examination of the Newborn Infant

The ideal state for a neurologic examination, state 3, is usually achieved 1 to 2 hours after feeding or, conversely, 1 to 2 hours before the next feed. 1

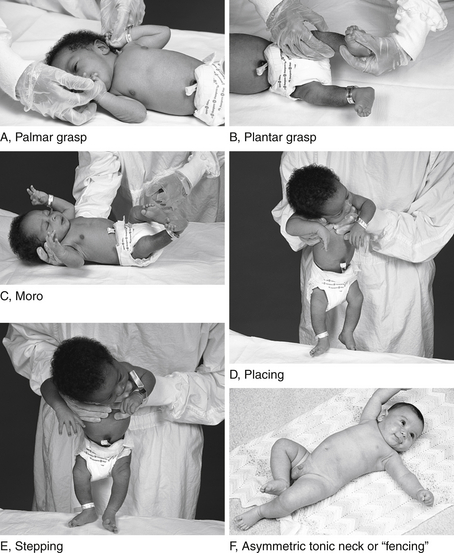

Developmental reflexes include both primitive and postural reflexes. Primitive reflexes are patterns of behavioral responses to stimulation that arise and extinguish at predictable ages in healthy newborns and infants. The familiar Moro reflex is elicited by sudden extension of the head in relation to the body, as with a light drop of the head ( Fig. 14-1). A newborn will respond by opening the hands and abducting and extending the arms and legs, followed by flexion. The Moro reflex is abnormal if asymmetric or depressed. Other examples of primitive reflexes include the palmar grasp, plantar grasp, glabellar, root, and suck reflexes. Postural reflexes determine the distribution of flexion or extension tone in the trunk and limb muscles depending on the orientation of the head and neck in space. The familiar “fencing posture” arises from the asymmetric tonic neck reflex, which is elicited by turning and holding the supine baby’s head to the left or right side for several seconds. The newborn reflexively responds by extending the arm and leg (by way of increased extension tone) on the side to which the face is pointing, while the other arm and leg flexes (by way of increased flexion tone) ( Table 14-1).

TABLE 14-1.

| REFLEX | AGE AT APPEARANCE | AGE AT DISAPPEARANCE |

| Moro | 30-34 weeks PMA | 3-6 months |

| Palmar grasp | 28-32 weeks PMA | 3-6 months |

| ATNR | 35 weeks PMA | 3 months |

The maneuver is performed by grasping the baby’s hand and trying to bring the baby’s elbow across the midline. In a healthy term infant the elbow can be brought no further than the midclavicular line on the same side. In the case of prematurity, hypotonia, or brachial plexus injury, the elbow is easily brought past the midline, like a scarf. 2

The term newborn should be able to follow an object both horizontally and vertically with the eyes. This may be assessed using a picture with contrasting black and white lines (e.g., Teller acuity targets); an object of a single bright color; or the examiner’s face, at about 10 inches from the baby. The examiner can move the object slowly across the field of vision to assess if eye movements are full and conjugate. Another method is to use a striped cloth or drum to elicit opticokinetic response and determine that eye movements are symmetric. Pupillary constriction responses to light develop between 30 and 32 weeks. 3

8. In newborns with facial paralysis, how is peripheral nerve involvement distinguished from a central etiology?

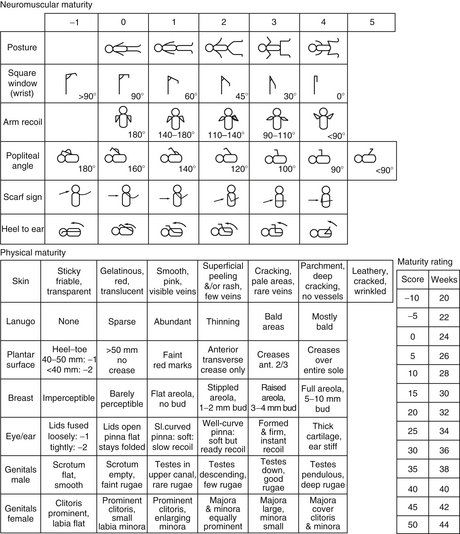

First, observe the position of the baby and the spontaneous movements. Observe the quantity and quality of the movements. Examine the tone by gentle flexion and extension of the limbs. Is there an associated paucity of movement of an arm or leg? Observe the rebound of the extremity; the rate at which a limb returns to its original position is helpful in gauging tone ( Fig. 14-3). Measuring the popliteal angle (which may be as great as 180 degrees at 28 weeks’ gestation but decreases to 110 degrees at term) allows for objective interobserver comparison of lower extremity tone. Head control can be gauged by either sitting the infant in the neutral position with good shoulder girdle support or pulling the baby off the surface of a bed (traction maneuver). 45

Figure 14-3. The Ballard scoring system. (From Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K, et al. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr 1991;119:417–423.)

The deep tendon reflexes develop, as does tone, several weeks earlier in the legs than in the arms, and the patellar and Achilles responses are attainable by 33 weeks’ gestation in most neonates. Note that when a knee-jerk response is obtained, a crossed adductor response may also occur as a normal variant up through 6 months of age.

Myoclonus is a brief, involuntary twitch or jerk of a muscle or group of muscles. It is frequently seen in healthy newborns, particularly when they are drowsy or sleeping. Benign neonatal myoclonus is very common, may persist for several weeks, and does not indicate a brain abnormality. Much less common are myoclonic seizures in newborns; these are myoclonic jerks that are shown on electroencephalography (EEG) to have an ictal correlate, meaning they are true epileptic seizures. Many babies with myoclonic seizures will have other abnormalities on exam to suggest their myoclonus is not benign; in some cases EEG is necessary to make the distinction. 6

Jitteriness describes a pattern of rapid, high frequency, vibratory, shaking movements that may fluctuate in amplitude and frequency. These movements may be spontaneous or may be triggered by touch or startle. Jitteriness is more common in babies with hypoglycemia or other metabolic disturbance, drug withdrawal, or mild encephalopathy. Jitteriness differs from myoclonus because myoclonus is a very brief, twitching contraction of muscles, whereas jitteriness is more often a sustained pattern of tremulous movements lasting seconds or longer. Jitteriness may be distinguished from seizures in that jitteriness tends to resolve by holding the baby or changing position of the baby or limb. Furthermore, jitteriness does not involve altered consciousness or autonomic changes. Myoclonus and jitteriness are but two examples of conditions that could be confused for genuine epileptic seizures in the neonate. 78

The Skull, Spine, and Brachial Plexus

The 50th percentile is 35 cm. Normal head circumference involves approximately 2 cm growth per month for 3 months, 1 cm growth per month for 3 more months, and then roughly 0.5 cm growth per month for the next 6 months, for a total of 12 cm in the first 12 months after birth. Premature infants should attain the head circumference of a healthy term infant, but illness and nutritional factors may slow the rate of growth. Relative to term infants, the head circumference of an otherwise healthy preterm infant may even be greater for the first 5 postnatal months, after which differences are less pronounced ( Table 14-2).

TABLE 14-2.

NORMAL HEAD CIRCUMFERENCE BY GESTATIONAL AGE

| GESTATIONAL AGE (Weeks) | HEAD CIRCUMFERENCE (Cm) |

| 28 | 26 |

| 32 | 30 |

| 36 | 33 |

| 40 | 35 |

Fenton TR. A new growth chart for preterm babies: Babson and Benda’s chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC Pediatr 2003;3:13.

15. How is head circumference affected in symmetric and asymmetric intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)?

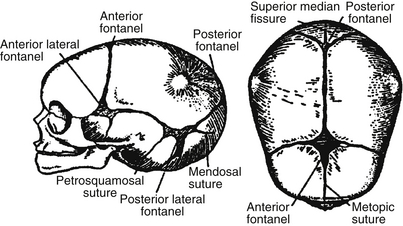

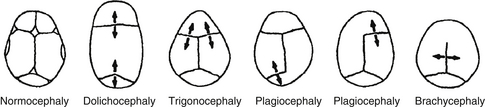

Craniosynostosis is the result of premature closure of a cranial suture. Normal cranial sutures are shown in Figure 14-4. Premature closure results in the arrest of growth perpendicular to the affected suture. Types of craniosynostosis and their appearance are illustrated in Figure 14-5. They involve the following:

Figure 14-4. Normal cranial sutures. (From Silverman FN, Kuhn JP, editors. Caffey’s pediatric x-ray diagnosis. 9th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. p. 5.)

Figure 14-5. Types of craniosynostosis. (From Gorlin JR. Craniofacial defects. In: Oski FA, Deangelis CD, Feigin RD, Warshaw JB, editors. Principles and practice of pediatrics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1994. p. 508.)

Dolichocephaly: sagittal synostosis (long, narrow head)

Dolichocephaly: sagittal synostosis (long, narrow head)

Brachycephaly: coronal synostosis (wide head)

Brachycephaly: coronal synostosis (wide head)

Acrocephaly: coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal

Acrocephaly: coronal, sagittal, and lambdoidal

Trigonocephaly: Metopic synostosis (pointed front of the head)

Trigonocephaly: Metopic synostosis (pointed front of the head)

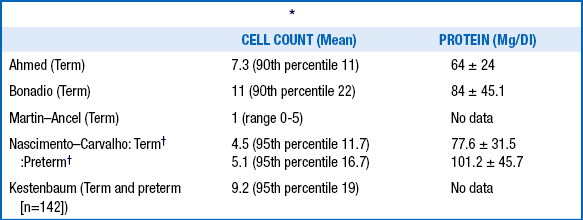

19. What are the normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) values for healthy neonates?

More than 15 cells in a CSF sample should be considered suspect for meninigitis and more than 20 cells elevated.

More than 15 cells in a CSF sample should be considered suspect for meninigitis and more than 20 cells elevated.

The CSF glucose concentration should be 70% to 80% of the blood glucose concentration.

The CSF glucose concentration should be 70% to 80% of the blood glucose concentration.

Protein concentrations in excess of 100 mg/dL in a nontraumatic tap from a term infant should be considered suspect.

Protein concentrations in excess of 100 mg/dL in a nontraumatic tap from a term infant should be considered suspect.

There is an inverse correlation between the protein concentration in CSF and gestational age.

There is an inverse correlation between the protein concentration in CSF and gestational age.

TABLE 14-3.

NORMAL CEREBROSPINAL FLUID VALUES IN HEALTHY TERM AND PRETERM INFANTS

∗All studies excluded traumatic lumbar puncture and were sterile; Ahmed and Bonadio did viral cultures. Excluded enteroviruses, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, seizures, non–central nervous system bacterial infection, and traumatic lumbar puncture (<500 red blood cells)

Fortunately, spinal cord injury is uncommon in neonates. One instance in which it can occur, however, is when excessive traction is applied to the neck during a difficult delivery, especially if there is shoulder dystocia. The resulting cord injury causes a flaccid quadriplegia with sparing of the face and cranial nerves. Secondly, an indwelling umbilical arterial catheter misplaced at T11 can obstruct the artery of Adamkiewicz, which feeds the anterior spinal artery. The resulting cord ischemia causes an irreversible paraplegia.

Erb palsy is an injury to the brachial plexus, particularly the upper trunk. This causes weakness in flexion at the shoulder and elbow. At rest, the arm of a baby with Erb palsy hangs by the side and is internally rotated, and there are limited or no spontaneous movements of the hand. The most common cause is injury to the brachial plexus during delivery, particularly in babies who are large for gestational age, or in cases of shoulder dystocia ( Table 14-4).

TABLE 14-4.

MAJOR PATTERN OF WEAKNESS WITH ERB (UPPER) BRACHIAL PLEXUS PALSY

| WEAK MOVEMENT | SPINAL CORD SEGMENT | RESULTING POSITION |

| Shoulder abduction | C5 | Adducted |

| Shoulder external rotation | C5 | Internally rotated |

| Elbow flexion | C5, C6 | Extended |

| Supination | C5, C6 | Pronated |

| Wrist extension | C6, C7 | Flexed |

| Finger extension | C6, C7 | Flexed |

| Diaphragmatic descent | C4, C5 | Elevated |

Most babies with brachial plexus injury recover well, although this may take as long as 6 months. As many as 30% of cases may have lasting deficits or will require intervention. In the initial weeks and months, physiotherapy may be useful. If problems persist, nerve and muscle transfer surgery may be warranted. 9

Malformations of the Central Nervous System

25. If the diagnosis of meningomyelocele is made prenatally, what treatment options can be considered?

Until recently, standard treatment for meningomyelocele was surgery after birth. However, a randomized trial showed that prenatal surgery (i.e., fetal surgery performed before 26 weeks of gestation) led to a reduction in the need for CSF shunt in the first year and improved motor outcomes at 30 months. Because of the maternal and fetal risks of this operation, treatment is now available only at highly specialized fetal surgery centers. 10

Many factors should be considered in formulating a neurologic prognosis. In general, the lower the level of the lesion, the better the prognosis. However, the presence and degree of hydrocephalus present at birth, in addition to the need for and any complications in shunting procedures (e.g., infection), also significantly affect outcomes. Any associated central nervous system (CNS) malformations, including agenesis of the corpus callosum, also contribute to morbidity. A child with a relatively low-lying lesion with an ACTII lesion and who has hydrocephalus is likely to have cognitive development in the normal range if there are no complications related to the shunting procedure. 11

28. In an infant born with meningomyelocele, how does the cord level of the lesion on initial evaluation predict long-term ambulation?

This assessment is accomplished by determining motor level and reflex level on examination ( Table 14-5). Sensory level assessment is less reliable in the newborn.

TABLE 14-5.

SPINAL LEVELS: MOTOR, REFLEXES, AND AMBULATION ∗

| LEVEL | MOTOR FUNCTION | AMBULATION |

| T-L2 | None or hip flexion only | None |

| L3-L4 | Knee extension, hip adduction | In 50%, with braces or other devices |

| L5-S1 | Knee flexion, ankle flexion | In 50%, some unaided |

| S2-S4 | Bowel and bladder | Almost all unaided |

∗S2-S4 levels have only bladder and bowel abnormalities, as do all higher levels.

Holoprosencephaly reflects an early failure of the rudimentary forebrain to divide into two halves, resulting in various kinds of single-ventricle anomalies. These range in severity from alobar, in which there are no distinct cerebral hemispheres, to lobar variants, in which division between cerebral lobes is incomplete. The alobar form is particularly severe in terms of neurologic dysfunction, may result in a wide spectrum of facial abnormalities, and may be observed in infants with trisomy 13 or 18 syndrome. 12

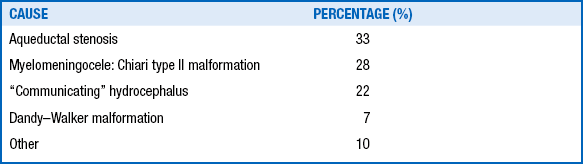

Structural malformations, such as aqueductal stenosis and ACTII malformation (usually associated with meningomyelocele and the Dandy–Walker malformation), are the most common causes of fetal hydrocephalus ( Table 14-6).

TABLE 14-6.

MAJOR CAUSES OF HYDROCEPHALUS OVERT AT BIRTH IN 127 CASES

Data from Mealey J Jr, Gilmor RL, Bubb MP. The prognosis of hydrocephalus overt at birth. J Neurosurg 1973:39:348–55; and McCullough DC, Balzer-Martin LA. Current prognosis in overt neonatal hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 1982;57:378–83.

With hydrocephalus the CSF is under pressure, causing a dilation of the ventricles proximal to the cause of obstruction. This condition will often worsen until surgical correction of the obstruction or placement of a CSF shunt. Ventriculomegaly, in contrast, occurs when ventricles are of a larger size than normal, but no evidence of increased CSF pressure exists. In cases of ventriculomegaly the cause is an underlying difference in brain development, and surgery is not indicated.

The vein of Galen malformation is rare overall, but it accounts for 30% of intracranial pediatric vascular abnormalities. A characteristic feature of the malformation is the presence of an arteriovenous shunt, which typically presents as high-output congestive heart failure in the neonatal period. There may be a bruit, sometimes quite loud, best heard over the posterior aspect of the newborn’s head. Sometimes there is head enlargement caused by an extrinsic aqueductal stenosis produced in the pons and midbrain by the bulk of the malformation. Only very rarely do these malformations present as bleeds at birth. Diagnosis is through neuroimaging (color Doppler and MRI and magnetic resonance angiography); ultimate treatment is through intravascular embolization or neurosurgery. 13

Neurocutaneous Syndromes

Café-au-lait spots are present in as many as 2% of infants; these vary in prevalence and are not always indicative of NF. Children with NF1 may have few or no café-au-lait spots at birth; these may become more obvious within the first year. Because of the high spontaneous mutation rate for this autosomal dominant disease, only about 50% of newly diagnosed cases of NF1 are associated with a positive family history. 1415

NF1 is an autosomal dominant disorder of a tumor-suppressor gene located on chromosome 17q11.2 that encodes neurofibromin, a negative regulator of the Ras oncogene. Characteristic café-au-lait-spots may appear at birth. Osseous lesions are usually apparent within the first year of life, and tumors of the optic chiasm present relatively early in life. Axillary freckling and peripheral, spinal, or central nerve NFs may develop in later childhood. Early ascertainment is difficult, and almost half of infants younger than 1 year of age do not fulfill the full criteria for this disorder. 16

of choroidal vessels of the eye leading to glaucoma and of the leptomeningeal vessels in the brain leading to seizures (Sturge–Weber syndrome). Almost invariably, the hemangioma in Sturge–Weber syndrome involves the trigeminal V1 area or is bilaterally distributed. Ophthalmologic assessment and radiologic studies (CT or MRI) are indicated for children who exhibit hemangiomas in the upper eyelid or forehead. This neurocutaneous syndrome arises sporadically and is not known to result from a specific genetic mutation. 17

Incontinentia pigmenti, or Bloch–Sulzberger syndrome, is an X-linked dominant disorder characterized by abnormalities of skin, teeth, hair, and eyes; mental retardation; seizures; skewed X-inactivation; and recurrent miscarriages of male fetuses. The first stage (i.e., vesicular stage) is characterized by lines of blisters, particularly on the extremities in newborns, that disappear in weeks or months. This is followed by stage 2 (i.e., verrucous stage), in which lesions develop at approximately age 3 to 7 months that are brown and hyperkeratotic, resembling warts. The final stage, stage 3 (i.e., pigmented stage), is characterized by whorled, swirling (marble cake–like) macular hyperpigmented lines that may fade with time. Rarely, neonatal seizures have been reported in this condition. 18

Intracranial Hemorrhage

47. What are the three major forms of extracranial hemorrhage that can occur after a difficult delivery?

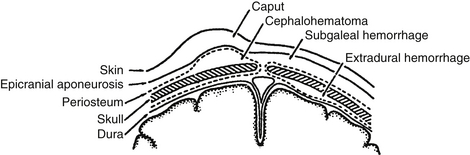

Caput succedaneum involves hemorrhagic edema of the presenting portion of the scalp and is common in vacuum extractions.

Caput succedaneum involves hemorrhagic edema of the presenting portion of the scalp and is common in vacuum extractions.

Cephalohematoma involves hemorrhage that is confined by the periosteum and therefore respects the sutures. Cephalohematomas sometimes calcify and may produce a cosmetic deformity.

Cephalohematoma involves hemorrhage that is confined by the periosteum and therefore respects the sutures. Cephalohematomas sometimes calcify and may produce a cosmetic deformity.

Subgaleal hemorrhage involves the area under the epicranial aponeurosis and may become large and pitting, even dissecting into the neck. This has the potential to cause clinically significant blood loss in the neonate. It is also associated with vacuum extractions ( Fig. 14-6).

Subgaleal hemorrhage involves the area under the epicranial aponeurosis and may become large and pitting, even dissecting into the neck. This has the potential to cause clinically significant blood loss in the neonate. It is also associated with vacuum extractions ( Fig. 14-6).

48. What are the major forms of intracranial hemorrhage?

Subdural hemorrhage (SDH) occurs in term infants with vaginal deliveries, more often with forceps or vacuum extraction, leading to bleeding in the subdural space where bridging veins can tear. Although more common supratentorially, SDH can occur beneath the tentorium cerebelli.

Subdural hemorrhage (SDH) occurs in term infants with vaginal deliveries, more often with forceps or vacuum extraction, leading to bleeding in the subdural space where bridging veins can tear. Although more common supratentorially, SDH can occur beneath the tentorium cerebelli.

IVH is most common in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) preterm babies because of the fragility of blood vessels in the germinal matrix, adjacent to the lateral ventricle. IVH has also been described in term newborns, particularly those with HIE. IVH in a term infant typically results from vasodilation and rupture of arteries within the choroid plexus.

IVH is most common in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) preterm babies because of the fragility of blood vessels in the germinal matrix, adjacent to the lateral ventricle. IVH has also been described in term newborns, particularly those with HIE. IVH in a term infant typically results from vasodilation and rupture of arteries within the choroid plexus.

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage occurs in the brain substance of neonates usually as a result of vascular malformation, arterial infarction, or venous thrombosis.

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage occurs in the brain substance of neonates usually as a result of vascular malformation, arterial infarction, or venous thrombosis.

It is important to note that a small intracranial hemorrhage is a common and often asymptomatic finding. In one series of neonates with MRI in the first 3 weeks, more than 50% of those born vaginally had some degree of intracranial hemorrhage. Therefore such findings on MRI should be interpreted with caution. 1920

Although there are variants, the most widely used systems group IVH into four categories.

Grade I hemorrhage: hemorrhage confined to the subependymal germinal matrix only

Grade I hemorrhage: hemorrhage confined to the subependymal germinal matrix only

Grade II hemorrhage: blood extending into the ventricle(s) without ventricular enlargement

Grade II hemorrhage: blood extending into the ventricle(s) without ventricular enlargement

Grade III hemorrhage: ventricular dilation in addition to intraventricular blood

Grade III hemorrhage: ventricular dilation in addition to intraventricular blood

Grade IV hemorrhage: grade III hemorrhage accompanied by hemorrhagic parenchymal infarction (formerly described by the misnomer “parenchymal extension”)

Grade IV hemorrhage: grade III hemorrhage accompanied by hemorrhagic parenchymal infarction (formerly described by the misnomer “parenchymal extension”)

53. What variables contribute to the development of IVH in a newborn?

Many of the following factors may be simultaneously present and contribute to neonatal IVH:

Prematurity, particularly VLBW or extremely-low-birth-weight (ELBW) infants

Prematurity, particularly VLBW or extremely-low-birth-weight (ELBW) infants

Increased venous pressure during delivery or fluctuating cerebral blood flow associated with mechanical ventilation

Increased venous pressure during delivery or fluctuating cerebral blood flow associated with mechanical ventilation

Increased cerebral blood flow associated with systemic hypertension or hypercarbia

Increased cerebral blood flow associated with systemic hypertension or hypercarbia

Hypotension followed by rapid volume expansion

Hypotension followed by rapid volume expansion

Coagulopathy caused by clotting factor deficiencies, thrombocytopenia, or platelet dysfunction (or a combination)

Coagulopathy caused by clotting factor deficiencies, thrombocytopenia, or platelet dysfunction (or a combination)

The immature, delicate, friable microvascular network in the germinal matrix

The immature, delicate, friable microvascular network in the germinal matrix

An inflammatory response with cytokine and immunomodulator production, most often from prenatal maternal infection, or infection or systemic inflammatory response in the neonate.

An inflammatory response with cytokine and immunomodulator production, most often from prenatal maternal infection, or infection or systemic inflammatory response in the neonate.

54. What are the major courses of progression of posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation and their rates of occurrence?

Of the persistent SPVD group, approximately 67% will have a spontaneous arrest, whereas 33% will continue to progress. In the spontaneous arrest group, 5% will have late progressive dilation. 21

55. What are some of the various treatment options for IVH and SVPD?

Close observation: This is the first step in managing the conditions. The infant’s clinical condition and head circumference should be closely followed. Head growth that exceeds 1 cm per week should be monitored with serial ultrasound scans documenting ventricular size.

Close observation: This is the first step in managing the conditions. The infant’s clinical condition and head circumference should be closely followed. Head growth that exceeds 1 cm per week should be monitored with serial ultrasound scans documenting ventricular size.

Trial of serial lumbar punctures: This controversial and unproven approach is considered by some to be the initial procedure when progressive ventricular dilation does not resolve spontaneously. An ultrasound scan should be obtained after 10 to 15 mL of CSF are withdrawn to see whether the procedure has been helpful in reducing ventricular size. Although this technique is widely used, clinical trials of serial lumbar puncture show no benefit in preventing later CSF shunt placement.

Trial of serial lumbar punctures: This controversial and unproven approach is considered by some to be the initial procedure when progressive ventricular dilation does not resolve spontaneously. An ultrasound scan should be obtained after 10 to 15 mL of CSF are withdrawn to see whether the procedure has been helpful in reducing ventricular size. Although this technique is widely used, clinical trials of serial lumbar puncture show no benefit in preventing later CSF shunt placement.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Although sometimes still used, acetazolamide (up to a high dose 100 mg/kg/day) combined with furosemide (1 to 2 mg/kg/day) has no clear benefit and increases the risk of nephrocalcinosis.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Although sometimes still used, acetazolamide (up to a high dose 100 mg/kg/day) combined with furosemide (1 to 2 mg/kg/day) has no clear benefit and increases the risk of nephrocalcinosis.

Ventricular drainage: This can be accomplished in numerous ways: direct external drainage, via an indwelling subcutaneous Ommaya reservoir, or by ventriculosubgaleal shunting. These are most often temporizing measures until an infant is able to undergo a more permanent procedure, usually a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The smaller the infant, the greater the likelihood of obstruction or infection (i.e., ventriculitis) by a shunting procedure. 222324

Ventricular drainage: This can be accomplished in numerous ways: direct external drainage, via an indwelling subcutaneous Ommaya reservoir, or by ventriculosubgaleal shunting. These are most often temporizing measures until an infant is able to undergo a more permanent procedure, usually a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The smaller the infant, the greater the likelihood of obstruction or infection (i.e., ventriculitis) by a shunting procedure. 222324

The incidence of neurologic sequelae is linked not only to the grade of hemorrhage but also to gestational age of the patient and the degree of parenchymal insult resulting from infarction and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL). Some series have shown a 5% incidence of neurologic sequelae (e.g., intellectual disability, spastic diplegia, and seizures) for grade I IVH, 15% for grade II, 33% for grade III, and almost 90% for grade IV with large infarction. However, long-term studies have demonstrated that at least 50% of ELBW and VLBW babies go on to have scholastic and behavioral abnormalities, with IVH being only one contributor to adverse outcomes. Recent data indicate that IVH that is not accompanied by white-matter injury has a better prognosis. 25262728

Preterm Brain Development and Periventricular Leukomalacia

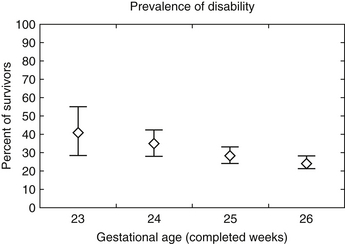

Gestational age significantly affects later prognosis. Overall, infants born extremely premature (22 to 25 weeks) are at a higher risk (50% to 75%) for death or neurodevelopmental impairments, including moderate or severe cerebral palsy (CP), bilateral blindness, and lower cognitive performance at age two. However, these risks are influenced not only by gestational age but also by sex, exposure to antenatal corticosteroids, twin or other multiple gestation, and birth weight. The EPICure study found fewer than half (41%) of children with a history of extreme prematurity (<26 weeks’ gestation) when tested at age 6 years were cognitively impaired compared with their classmates. The rates of severe, moderate, and mild disability were 22%, 24%, and 34%, respectively. Disabling CP was present in 12% ( Fig. 14-7).

Although prognosis is much more optimistic for infants born late preterm, some increased risk of learning or behavior problems remains. One recent study found the risk of developmental delay or disability was increased by 36% among babies born between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestation compared with those born at term. 293031

Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) is white matter necrosis, seen mostly in preterm babies. This white matter necrosis surrounding the ventricular walls may be cystic (with fluid-filled cavities) or noncystic. However, white matter injury can extend far beyond the periventricular region; the anterior and posterior periventricular regions are most commonly affected. The former region is where white matter fibers pass to the legs, accounting for subsequent leg spasticity, and the latter, posterior area is responsible for the visual abnormalities of PVL.

Hypoxia-ischemia: The blood vessels supplying the white matter surrounding the lateral ventricles are arrayed radially, thus creating vascular end zones. In sick preterm infants autoregulation may be blunted or absent. Thus systemic hypotension can result in low cerebral blood flow and poor perfusion to the deep periventricular vascular regions. Low cerebral blood flow may lead to brain tissue hypoxia followed by glutamate and free radical damage to the preoligodendrocytes, the precursor cells to the oligodendrocytes that form the white matter.

Hypoxia-ischemia: The blood vessels supplying the white matter surrounding the lateral ventricles are arrayed radially, thus creating vascular end zones. In sick preterm infants autoregulation may be blunted or absent. Thus systemic hypotension can result in low cerebral blood flow and poor perfusion to the deep periventricular vascular regions. Low cerebral blood flow may lead to brain tissue hypoxia followed by glutamate and free radical damage to the preoligodendrocytes, the precursor cells to the oligodendrocytes that form the white matter.

Maternal or fetal infections: Infection can produce cytokines that may cross the blood–brain barrier of the fetus. The cytokines set off an inflammatory cascade and activate white matter microglia that secrete products that damage those same preoligodendrocytes. 3233

Maternal or fetal infections: Infection can produce cytokines that may cross the blood–brain barrier of the fetus. The cytokines set off an inflammatory cascade and activate white matter microglia that secrete products that damage those same preoligodendrocytes. 3233

In the first days and weeks after injury, PVL may appear as a bright “periventricular flare.” Approximately 2 to 3 weeks later, some infants may exhibit cystic changes which can be detected on cranial ultrasound. When VLBW babies reach term gestation, DEHSI and ventriculomegaly can be observed on T2 MRI images, in addition to the aforementioned cysts and infarcts. After 6 months to 2 years, the MRI will demonstrate periventricular hypomyelination and white matter scarring (particularly, but not exclusively, in the frontal and posterior periventricular areas), ventriculomegaly, ventricular wall scalloping and irregularity, thinning of the corpus callosum, and brain atrophy. In the setting of PVL, volumetric MRI studies also commonly show shrinkage of gray matter in the cortex and the deep lentiform nuclei. 34

The principal sequelae include spastic diplegia and visual and cognitive deficits.

Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

Recall first that the syndrome of ANE (see Question 3) is not synonomous with HIE. HIE is a specific neurologic syndrome in the newborn infant that results from low oxygen and blood delivery to the brain. For an intrapartum event to contribute to neonatal brain injury, the following should be present: (1) a history of intrauterine distress, (2) depression at birth, and (3) an obvious neonatal neurologic syndrome in the immediate postnatal period. 35

65. What are the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) criteria to define an intrapartum event sufficient to cause CP?

Essential criteria (must meet all four):

Evidence of a metabolic acidosis in fetal umbilical cord arterial blood obtained at delivery (pH <7 and base deficit ≥12 mmol/L)

Evidence of a metabolic acidosis in fetal umbilical cord arterial blood obtained at delivery (pH <7 and base deficit ≥12 mmol/L)

Early onset of severe or moderate neonatal encephalopathy in infants born at 34 or more weeks of gestation

Early onset of severe or moderate neonatal encephalopathy in infants born at 34 or more weeks of gestation

Resulting CP of the spastic quadriplegic or dyskinetic type

Resulting CP of the spastic quadriplegic or dyskinetic type

Exclusion of other identifiable etiologies, such as trauma, coagulation disorders, infectious conditions, or genetic disorders

Exclusion of other identifiable etiologies, such as trauma, coagulation disorders, infectious conditions, or genetic disorders

A sentinel (signal) hypoxic event occurring immediately before or during labor

A sentinel (signal) hypoxic event occurring immediately before or during labor

A sudden and sustained fetal bradycardia or the absence of fetal heart rate variability in the presence of persistent, late, or variable decelerations, usually after a hypoxic sentinel event when the pattern was previously normal

A sudden and sustained fetal bradycardia or the absence of fetal heart rate variability in the presence of persistent, late, or variable decelerations, usually after a hypoxic sentinel event when the pattern was previously normal

Apgar scale score of 0 to 3 beyond 5 minutes

Apgar scale score of 0 to 3 beyond 5 minutes

Onset of multisystem involvement within 72 hours of birth

Onset of multisystem involvement within 72 hours of birth

Early imaging study showing evidence of acute nonfocal cerebral abnormality

Early imaging study showing evidence of acute nonfocal cerebral abnormality

66. How often is neonatal encephalopathy caused by intrapartum asphyxia?

Although definitions and methods of study vary, most research suggests that ANE is not usually the result of isolated intrapartum HIE. For example, one case-control study identified numerous risk factors for ANE, such as maternal infertility treatment, maternal thyroid disease, and severe preeclampsia, all of which were antenatal. Similarly, a Scottish neuropathology study examined the brains of infants with ANE who died soon after delivery. Among 53 neonates initially thought clinically to have “birth asphyxia,” the majority had histopathologic evidence of brain injury that could have only predated labor and delivery. 3637

Some babies with ANE have evidence of hypoxic-ischemic injury that started before labor and delivery. For example, one retrospective series of babies with ANE found that at initial presentation to the hospital 70% already had absent fetal movements and nonreactive fetal heart rate tracings (absence of spontaneous cardiac accelerations), and many had chronic meconium staining. This constellation of findings is consistent with a prior hypoxic-ischemic event. Additional evidence has recently emerged that babies with an admission history of “reduced fetal movements” had already sustained a brain injury; these patients may not benefit from therapeutic hypothermia and may show a “subacute” injury pattern on MRI. 3839

68. What are the Sarnat encephalopathy stages, and how are they clinically useful?

Stage 1: Mild encephalopathy in a newborn infant who is hyperalert, irritable, and oversensitive to stimulation. There is evidence of sympathetic overstimulation with tachycardia, dilated pupils, and jitteriness.

Stage 1: Mild encephalopathy in a newborn infant who is hyperalert, irritable, and oversensitive to stimulation. There is evidence of sympathetic overstimulation with tachycardia, dilated pupils, and jitteriness.

Stage 2: Moderate encephalopathy with the newborn displaying lethargy, hypotonia, and proximal weakness. There is parasympathetic overstimulation with low resting heart rate, small pupils, and copious secretions. The EEG is abnormal, and 70% of infants will have seizures.

Stage 2: Moderate encephalopathy with the newborn displaying lethargy, hypotonia, and proximal weakness. There is parasympathetic overstimulation with low resting heart rate, small pupils, and copious secretions. The EEG is abnormal, and 70% of infants will have seizures.

Stage 3: Severe encephalopathy with a stuporous, flaccid newborn and absent reflexes. The newborn may have seizures and has an abnormal EEG with decreased background activity, voltage suppression, or both.

Stage 3: Severe encephalopathy with a stuporous, flaccid newborn and absent reflexes. The newborn may have seizures and has an abnormal EEG with decreased background activity, voltage suppression, or both.

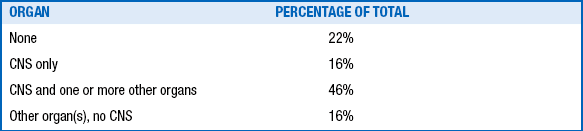

When hypoxia-ischemia does produce ANE, it is typically expected that other body organs and systems are also affected, although this does not occur in every case. This could clinically include (1) hypoxic-ischemic depression of the myocardium (hypotension requiring volume expanders and pressor support); (2) acute renal failure (low urine output, hematuria, and climbing creatinine values); (3) hepatopathy with elevated liver enzymes and sometimes coagulopathy owing to multiple clotting factor deficiencies; (4) necrotizing enterocolitis; and (5) muscle ischemia resulting in excessively elevated serum creatine kinase. Multisystem dysfunction is not unique to HIE, however, and can be seen in other conditions, such as septic shock ( Table 14-7).

TABLE 14-7.

MANIFESTATIONS OF ORGAN INJURY IN TERM ASPHYXIATED INFANTS ∗

∗Cumulative total of 107 term infants; definition of asphyxia in both series included umbilical cord arterial pH <7.2.

Data from Perlman JM, Tack ED, Martin T, et al. Acute systemic organ injury in term infants after asphyxia. Am J Dis Child 1989;143:617–20; and Martin–Ancel A, Garcia–Alix A, Gaya F, et al. Multiple organ involvement in perinatal asphyxia. J Pediatr 1995;127:786–93.

Brain monitoring is the only direct way to measure the function of the brain after HIE or any cause of ANE. The gold standard for neonatal brain monitoring is continuous video-EEG recording. This allows the most accurate description of the EEG background, a sensitive and specific tool to formulate a neurologic prognosis. It is also the most objective method to diagnose and accurately quantify electrographic seizures, which occur in up to two of every three neonates after HIE. When continuous video-EEG monitoring is unavailable, amplitude-integrated EEG ([aEEG], popularly called cerebral function monitoring) or a series of routine EEG examinations are also very useful. 40

The patterns of brain injury vary with gestational age and the duration and severity of the asphyxia event ( Table 14-8).

TABLE 14-8.

SITES OF PREDILECTION FOR THE DIFFUSE FORM OF HYPOXIC-ISCHEMIC SELECTIVE NEURONAL INJURY IN PREMATURE AND TERM NEWBORNS ∗

| BRAIN REGION | PREMATURE | TERM NEWBORN |

| Cerebral neocortex | + | |

| Hippocampus | ||

| Sommer sector | + | |

| Subiculum | + | |

| Deep nuclear structures | ||

| Caudate–putamen | + | + |

| Globus pallidus | + | + |

| Thalamus | + | + |

| Brainstem | ||

| Cranial nerve nuclei | + | + |

| Pons (ventral) | + | + |

| Inferior olivary nuclei | + | + |

| Cerebellum | ||

| Purkinje cells | + | |

| Granule cells (internal, external) | ± | ± |

| Spinal cord | ||

| Anterior horn cells (alone) | ± | |

| Anterior horn cells and contiguous cells (? infarction) | ± |

There are several different HIE pathways, which are associated with their own distinctive pattern of neonatal brain injury. In acute, profound, near total asphyxia, the hypoxia-ischemia is actually caused by an abrupt prolonged terminal bradycardia. Prolonged terminal bradycaria results from a uterine rupture, cord prolapse, sudden total placental abruption, or maternal cardiac arrest, among other conditions. In acute, near total asphyxia, brain injury is mostly confined to the deep gray structures (globus pallidus, caudate, putamen, and thalami) and sometimes the gray and white matter of the bilateral perirolandic regions. A different type of injury is seen in partial prolonged asphyxia owing to a progressive but more gradual loss of brain oxygenation and perfusion. Slowly progressive placental abruption is an example of one condition that leads to a partial prolonged type of asphyxia causing a watershed brain injury pattern with prominent edema of the deep white matter, creating slitlike lateral ventricles. These patterns of insult are not mutually exclusive, and some babies show both watershed and deep gray lesions. There is growing evidence that maternal–fetal inflammation or infection may predispose the fetus to hypoxic-ischemic injury. Furthermore, maternal–fetal infection or inflammation can produce a clinical syndrome and MRI pattern that closely mimic genuine HIE. 41424344

73. What are currently the most useful clinical and laboratory tools when estimating the prognosis in cases of HIE?

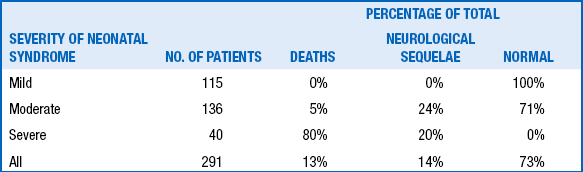

Clinically, judicious use of the previously discussed Sarnat scoring method is helpful. Newborns with stage I generally do well. Surviving stage III newborns are at very high risk for spastic quadriplegia, intellectual disability, and seizures. Outcomes after Sarnat stage II are the most difficult to predict, and additional investigations may be very useful to refine the neurologic prognosis ( Table 14-9). An initial cord pH below 7, elevated serum lactate levels, evidence of multisystem involvement, and increased creatine kinase values in blood also have been correlated to guarded prognosis.

TABLE 14-9.

OUTCOME OF TERM INFANTS WITH HYPOXIC-ISCHEMIC ENCEPHALOPATHY AS A FUNCTION OF SEVERITY OF NEONATAL NEUROLOGICAL SYNDROME ∗

∗Derived from 291 full-term infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Data from Robertson C, Finer N. Term infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: outcome at 3.5 years. Dev Med Child Neurol 1985;27:473–84; and Thornberg E, Thiringer K, Odeback A, et al. Birth asphyxia: incidence, clinical course and outcome in a Swedish population. Acta Paediatr 1995;84:927–32.

74. What are currently the most useful neurodiagnostic laboratory tools in estimating prognosis in cases of HIE?

The EEG may be very useful. A normal EEG background in the first 3 days has 90% to 100% specificity for a good outcome. Interictal EEG patterns of burst suppression and inactive low-voltage background have extremely guarded prognoses. This is particularly true when still present 24 hours after birth. MRI may also be helpful. Abnormalities appear early on diffusion-weighted images in 3 to 6 hours, and then 2 to 3 days later on T1- and T2-weighted sequences. An abnormal signal in the posterior limb of the internal capsule has a positive predictive value for motor impairment of nearly 100% when performed in infants of term equivalent age. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) may also help define functional abnormality. 4546

Apparent diffusion coefficient values from the posterior limb of the internal capsule are significantly greater in term infants with HIE who ultimately survive. Among survivors a reduced apparent diffusion coefficient value in the posterior limb on the internal capsule is associated with a greater probability of an abnormal neuromotor outcome. In contrast, an elevated N-acetylaspartate–to–total–creatine ratio is associated with a higher likelihood of a normal outcome at 18 months. Most important, the presence of an abnormal lactate peak predicts an abnormal outcome with a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 80%. 474849

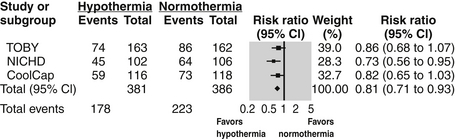

Multiple large, randomized, controlled trials have now shown therapeutic hypothermia is efficacious in reducing neurodevelopmental disability after HIE ( Fig. 14-8). Therapeutic hypothermia (or “cooling”) must be initiated within 6 hours of birth and continued for 72 hours to lower the neonate’s body temperature to a target of 33.5° to 35° centigrade. Cooling may either be implemented through cooling blankets or selective head-cooling devices.

Figure 14-8. Summary of meta-analysis demonstrating beneficial effect of hypothermia on outcomes following neonatal HIE. (Edwards AD, Brocklehurst P, Gunn AJ, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ 2010;340:c363.)

All affected newborns require supportive treatment. This includes maintenance of cardiorespiratory function, including ventilation when needed. Newborns with HIE require careful fluid, glucose, and electrolyte management, and the clinician must remember that the asphyxial insult may involve myocardium, kidneys, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Finally, there must be a high suspicion for, and appropriate treatment of, seizures. 5051525354

Stroke

In any sick newborn with seizures or a focal neurologic abnormality, the suspicion for an underlying structural lesion should be high. Ultrasound examination may be useful at the bedside for detecting strokes, though sensitivity is highly user dependent. CT scans are superior to ultrasound in the acute setting; however, they lack the detail of MRI and expose the infant to radiation. MRI is thus the diagnostic test of choice. Diffusion-weighted images can detect recent strokes from as little as 6 hours to 7 days after the event. Traditional MRI sequences (T1 and T2) are adequate for more remote strokes. 55

78. What is the further diagnostic work-up of perinatal stroke? ( Table 14-10)

TABLE 14-10.

SUGGESTED DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP OF NEONATAL STROKE

| HISTORY | FACTORS NOTED IN TABLE 7-2 |

| Radiologic examination | Cranial ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging/angiography/venography with diffusion-weighted imaging If appropriate, echocardiography, ultrasound of neck vessels or indwelling catheters |

| Laboratory examination ∗ | Coagulopathy work-up: proteins C and S, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden, anticardiolipin Ab, lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid Ab, fasting homocysteine, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase C 677T mutation, prothrombin 20210 variant, lipoprotein (a), fibrinogen, plasminogen, factor VIIIC |

| Placental evaluation | Complete pathologic examination of placenta |

∗There is no consensus regarding the number of these tests that should be performed in cases of ischemic perinatal stroke.

Once stroke is diagnosed, an etiologic work-up should be undertaken, along with evaluation for comorbidities. The placenta should undergo a careful histopathologic examnination because it is a likely source for emboli. Infants with stroke should undergo a complete blood count to rule out polycythemia; lupus anticoagulant and protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III levels should be measured. Genetic tests looking for factor V Leiden mutation, MTHFR mutation, and prothrombin 20210G mutation are indicated. An echocardiogram to rule out a cardiac source of emboli should also be done, particularly if any cardiac signs are present or if the infant has experienced a multifocal stroke. An EEG might demonstrate electrographic seizures, slowing, or attenuation. Magnetic resonance angiography and venography help visualize the cerebral vessels to rule out pathology. 56

Initial management includes general medical support and administration of antiseizure medications if the child has seizures. Anticoagulation is controversial and is probably not indicated unless an active source of emboli is apparent. In a recent review of outcomes in infants with strokes in the perinatal period, 40% of infants were judged to be normal, 57% were neurologically or cognitively abnormal, and 3% died. 5758

Sinovenous thrombosis has been increasingly recognized, and its true incidence likely exceeds early estimates of 1 per 100,000. Identifiable causes are those that would increase the overall risk of thrombosis in a newborn. They include dehydration, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and congenital heart disease. Similarly, genetic thrombophilias are a risk factor. Many cases are multifactorial. Newborns have a higher risk for sinovenous thrombosis than members of any other age group. 59

The clinical presentation is usually nonspecific; lethargy and poor feeding are the most common signs. Seizures are another initial early sign. Neuroimaging is required for diagnosis. Although thrombus may be directly visualized on MRI, other supportive findings are absence of Doppler flow through the affected vein on cranial ultrasound and decreased flow on magnetic resonance venography. The straight sinus and superior sagittal sinus are most often involved, although multiple sinuses are often affected. The diagnosis may be difficult because deeper thrombosis is harder to visualize. 6061

Although the location and size of injury play important roles in shaping outcomes, prognosis after sinovenous thrombosis is generally worse than that after arterial stroke. One prospective study of 104 newborns found 61% at follow-up had either died or experienced a disability, including epilepsy, moderate to severe language deficits, and CP. 62

Perinatal Illness and Later CP

CP is a nonprogressive disorder of motor function (“a palsy”) of CNS (“cerebral”) origin occurring usually in utero or early in life (up to age 2 years). Intellectual deficit is not implicit in CP, although it accompanies the motor disability in a high percentage of cases. The overall prevalence of CP is 1.7 to 2 of 1000 among survivors at the age of 1 year. Premature infants have the highest incidence of CP, although most infants with CP have birth weights greater than 2500 g. The lower the birth weight and gestational age, the greater the chance for the child to develop CP. Although the CNS injury that leads to CP usually occurs in the perinatal period, the signs of CP may not be obvious until after the first year. 63

Hypotonia is more common than hypertonia and spasticity in the first year.

Hypotonia is more common than hypertonia and spasticity in the first year.

Infants have a limited variety of volitional movements for evaluation.

Infants have a limited variety of volitional movements for evaluation.

Substantial myelination takes months to evolve and may delay the clinical picture of abnormal tone and increased deep tendon reflexes.

Substantial myelination takes months to evolve and may delay the clinical picture of abnormal tone and increased deep tendon reflexes.

Choreoathetosis (e.g., that resulting from acute kernicterus) often is not obvious before the first birthday.

Choreoathetosis (e.g., that resulting from acute kernicterus) often is not obvious before the first birthday.

86. How does maternal infection affect the incidence of CP in term children of normal birth weight?

Maternal temperature above 38˚ C (100.4˚ F) during labor or a clinical diagnosis of chorioamnionitis is associated with a markedly (ninefold) increased risk of CP, especially spastic quadriplegic CP (19-fold increase). Remember that approximately 50% of maternal cases of chorioamnionitis are subclinical. 6465

87. What is the evidence to suggest that inflammatory cytokines are associated with prematurity and development of CP?

The inflammatory response to infection activates a number of cytokines and chemokines, which in turn may trigger preterm contractions, cervical ripening, rupture of the membranes, and prematurity. The levels of interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8, IL-9, and tumor necrosis factor are independent risk factors for the subsequent development of CP at the age of 3 years. 6667

Neonatal Seizures

There are two ways to define neonatal seizures: electrographically and clinically. EEG seizures are defined as a sudden (paroxysmal) attack of abnormal, hypersynchronous electrical discharges in the brain. Clinical seizures are a sudden (paroxysmal) attack of abnormal-appearing movements, behaviors, or autonomic functions. There is a very imperfect overlap between clinical and EEG seizures. Clinical seizures that are specifically linked to simultaneous EEG seizures are called electroclinical. Abnormal-appearing clinical seizures that occur without simultaneous EEG seizures are classified as non-epileptic seizures. EEG seizures that do not provoke any outwardly visible motor or autonomic signs are called subclinical, silent, or occult seizures.

90. What clinical signs may be evident during seizures?

Autonomic changes: Sudden, unexplained autonomic signs such as apnea, episodic hypertension or tachycardia, flushing, tearing, or salivation may be the only outward manifestation of a seizure.

Autonomic changes: Sudden, unexplained autonomic signs such as apnea, episodic hypertension or tachycardia, flushing, tearing, or salivation may be the only outward manifestation of a seizure.

Clonic seizures: These are characterized by sustained, repetitive, rhythmic jerking movements of a muscle group. Clonic seizures may be focal or multifocal, involving several body parts, often in a migrating fashion.

Clonic seizures: These are characterized by sustained, repetitive, rhythmic jerking movements of a muscle group. Clonic seizures may be focal or multifocal, involving several body parts, often in a migrating fashion.

Focal tonic seizures: These are characterized by abrupt changes in muscle tone. Sustained changes in muscle tone modify the body’s posture. Focal tonic seizures may produce posturing of an arm or leg or the extraocular muscles, leading to a sustained, unnatural deviation of both eyes to one side.

Focal tonic seizures: These are characterized by abrupt changes in muscle tone. Sustained changes in muscle tone modify the body’s posture. Focal tonic seizures may produce posturing of an arm or leg or the extraocular muscles, leading to a sustained, unnatural deviation of both eyes to one side.

Multiple studies have shown that upward of 80% of confirmed EEG seizures in the neonate are invisible to the naked eye and have no outward signs detectable by bedside caregivers. Accurate detection and diagnosis of neonatal seizures therefore requires EEG monitoring. 68

The sensitivity of aEEG for seizure detection depends in part on the experience of the user in interpreting these recordings. Although experts have reported theoretical sensitivity of approximately 80%, most users correctly identify fewer than half of seizures using aEEG alone. 69

Vitamin-responsive neonatal seizures, especially vitamin B6 dependency, should always be considered in seizures refractory to treatment, particularly without a clear symptomatic etiology. Other vitamin and cofactor deficiencies with the potential to cause seizures include molybdenum, pyridoxal phosphate, and folinic acid. 70

There are increasing numbers of recognized malignant epilepsy syndromes with onset in the neonatal period. Many of these are characterized by refractory seizures, a characteristic EEG pattern, and a poor prognosis. Examples include early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with burst-suppression (Ohtahara syndrome) and early myoclonic epilepsy. Some of these syndromes are now understood to have multiple underlying causes, including structural lesions, metabolic disease, and genetic mutations. A malignant epilepsy syndrome should be suspected when no symptomatic cause for seizures can be found and when seizures remain refractory to initial treatment. 717273

Seizures in a “well baby” may be caused by simple hypocalcemia or hypoglycemia or may be the first sign of a benign neonatal epilepsy. Hypocalcemia and hypocalcemic tetany resulting from milks with a high phosphate load are now rarely seen in the United States. Benign neonatal epilepsy syndromes have been described and have a relatively good prognosis for seizure remission and development. The familial syndromes are associated with genetic mutations in sodium or potassium channels. 74

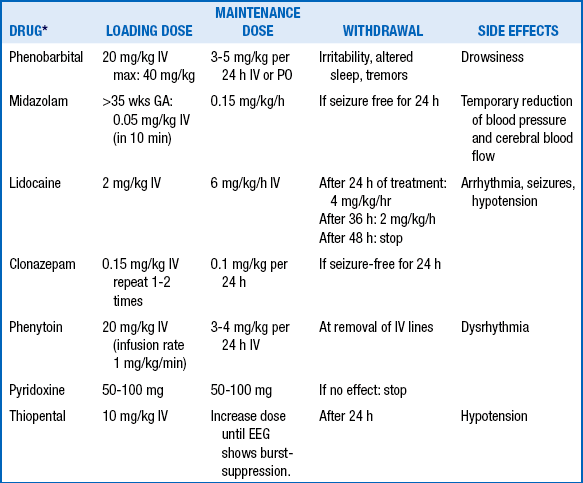

The initial treatment of neonatal seizures should always be aimed at correcting the underlying disorder and maintaining hemodynamic and respiratory stability. First-line pharmacologic treatment for neonatal seizures is usually phenobarbital, followed by phenytoin. Although their efficacy has never been demonstrated by a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, these drugs have the advantage of having been used for a long time in newborns. Phenobarbital or phenytoin are effective in suppressing seizures in less than half of neonates. When one drug fails, adding a second results in a 70% success rate. Third-line treatments (e.g., benzodiazepenes) are variable ( Table 14-11). 7576

TABLE 14-11.

ANTICONVULSANT DRUGS FOR NEONATAL SEIZURES

∗For each drug, monitoring should include blood pressure, respiratory status, and EEG. For lidocaine, ECG monitoring is a special consideration.

From van de Bor M. The recognition and management of neonatal seizures. Curr Paediatr 2002;12:382–7.

Neuromuscular Disorders

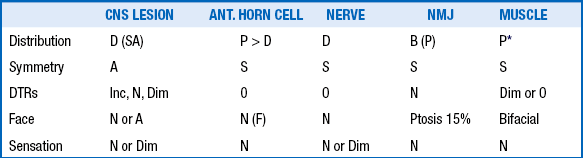

Central hypotonia results from a CNS lesion—a problem in the brain or spinal cord. Peripheral hypotonia results from a lesion in the peripheral nervous system—the nerves, neuromuscular junction, or muscles. Central should not be confused with axial or “truncal” hypotonia, which describes hypotonia affecting primarily the core trunk muscles. Similarly, peripheral hypotonia should not be confused with “appendicular” hyptonia in the extremities.

TABLE 14-12.

Chromosomal disorders

Other genetic defects

Acute hemorrhagic and other brain injury

Hypoxic/ischemic encephalopathy

Peroxisomal disorders (e.g., Zellweger syndrome, neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy)

Metabolic defects

Drug intoxication

Benign congenital hypotonia

105. What are the components of the lower motor neuron? Why is it useful to think in terms of these anatomic entities when evaluating a floppy newborn infant?

It is useful to think anatomically because clinical localization is facilitated in this way ( Table 14-13). The components of the lower motor neuron from the spinal cord to most peripheral part are as follows:

TABLE 14-14.

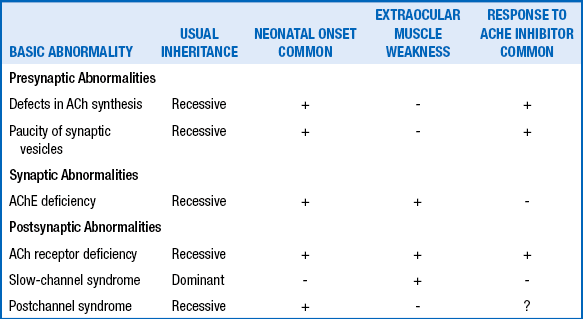

NEUROMUSCULAR DISEASES IN THE HYPOTONIC INFANT AND CHILD

| Anterior horn cell or peripheral nerve | Spinal muscular atrophies Hypoxic-ischemic myelopathy Traumatic myelopathy Neurogenic arthrogryposis Congenital neuropathies: axonal Hypomyelinating Dejerine–Sottas disease Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy Giant axonal neuropathy Metabolic inflammatory |

| Neuromuscular junction | Transient neonatal myasthenia gravis Congenital myasthenic syndromes Hypermagnesemia Aminoglycoside toxicity Infantile botulism |

| Muscle | Congenital muscular dystrophies Congenital myotonic dystrophy Infantile facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy Congenital myopathies Metabolic myopathies Mitochondrial myopathies |

106. What are the tests to confirm lower motor neuron disease?

The physical examination shows weakness, atrophy, diminished to absent deep tendon reflexes, and sometimes fasiculations. Ancillary testing includes blood creatine phosphokinase measurement, serum carnitine measurement, motor nerve conduction velocities, needle electromyography (EMG), DNA testing, and muscle biopsy.

Elevated serum creatine phosphokinase values beyond the seventh postnatal day suggest active muscle disease, most commonly one of the congenital muscular dystrophies.

Elevated serum creatine phosphokinase values beyond the seventh postnatal day suggest active muscle disease, most commonly one of the congenital muscular dystrophies.

Low carnitine levels either suggest the very rare primary carnitine deficiency or result from fatty acid or organic acid abnormalities.

Low carnitine levels either suggest the very rare primary carnitine deficiency or result from fatty acid or organic acid abnormalities.

Abnormally low nerve conduction velocities suggest a neuropathy but are reported in 30% to 50% of cases of anterior horn cell disease. Needle EMG studies are helpful to distinguish a neuropathic from a myopathic process. Myotonia on insertion is rare in neonatal myotonic dystrophy but is invariably present in Pompe disease (i.e., acid maltase deficiency).

Abnormally low nerve conduction velocities suggest a neuropathy but are reported in 30% to 50% of cases of anterior horn cell disease. Needle EMG studies are helpful to distinguish a neuropathic from a myopathic process. Myotonia on insertion is rare in neonatal myotonic dystrophy but is invariably present in Pompe disease (i.e., acid maltase deficiency).

DNA analysis is useful to confirm specific diseases; spinal muscular atrophy, myotonic dystrophy, and Prader–Willi syndrome are examples of conditions in which genetic diagnosis is possible.

DNA analysis is useful to confirm specific diseases; spinal muscular atrophy, myotonic dystrophy, and Prader–Willi syndrome are examples of conditions in which genetic diagnosis is possible.

In some cases muscle biopsy (with both histologic and biochemical analysis) is the only way to make a precise diagnosis.

In some cases muscle biopsy (with both histologic and biochemical analysis) is the only way to make a precise diagnosis.

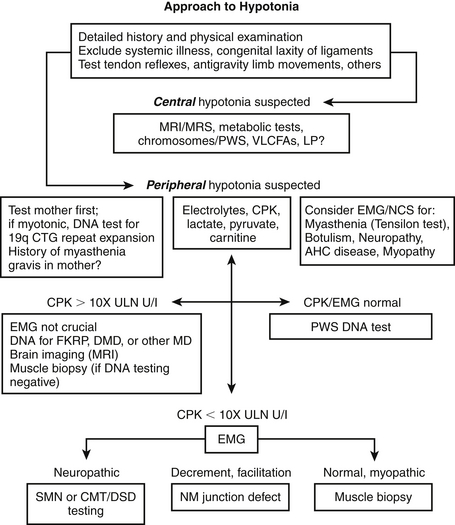

107. How should infants with hypotonia be evaluated?

Our stepwise approach to the diagnostic investigation of infantile hypotonia is as follows ( Figure. 14-9):

Figure 14-9. Stepwise approach to hypotonia. CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; EMG, electromyography; FKRP, fukutin-related protein; MD, muscular dystrophy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NCS, nerve conduction study; NM, neuromuscular; SMN, survival motor neuron; VLCFAs, very-long-chain fatty acids.

Conduct a detailed history (history of polyhydraminios, intrauterine growth retardation, reduced fetal movement), and physical examination, including tests of muscle stretch reflexes, antigravity limb movements, and contractures.

Conduct a detailed history (history of polyhydraminios, intrauterine growth retardation, reduced fetal movement), and physical examination, including tests of muscle stretch reflexes, antigravity limb movements, and contractures.

Exclude systemic illness and congenital laxity of ligaments.

Exclude systemic illness and congenital laxity of ligaments.

If central hypotonia is suspected, conduct MRI or MR spectroscopy studies, metabolic studies, and genetic testing for Prader-Willi syndrome (deletion of 15q11-13) and Down syndrome (trisomy 21). Also test for very–long-chain fatty acids and/or perform other peroxisomal tests. Consider lumbar puncture for measurement of cerebrospinal fluid lactate, glucose, and protein and, if indicated, cerebrospinal fluid neurotransmitter testing.

If central hypotonia is suspected, conduct MRI or MR spectroscopy studies, metabolic studies, and genetic testing for Prader-Willi syndrome (deletion of 15q11-13) and Down syndrome (trisomy 21). Also test for very–long-chain fatty acids and/or perform other peroxisomal tests. Consider lumbar puncture for measurement of cerebrospinal fluid lactate, glucose, and protein and, if indicated, cerebrospinal fluid neurotransmitter testing.

If peripheral hypotonia is suspected, first examine the mother. If she has signs of myotonic dystrophy, perform a DNA test for 19qCTG repeat expansion in the child. Elicit any history of autoimmune myasthenia gravis in the mother.

If peripheral hypotonia is suspected, first examine the mother. If she has signs of myotonic dystrophy, perform a DNA test for 19qCTG repeat expansion in the child. Elicit any history of autoimmune myasthenia gravis in the mother.

Consider electromyography and nerve conduction studies to evaluate for myasthenia, botulism, neuropathy or anterior horn cell disease, and myopathy. Consider performing a Tensilon test if myasthenic syndrome is suspected.

Consider electromyography and nerve conduction studies to evaluate for myasthenia, botulism, neuropathy or anterior horn cell disease, and myopathy. Consider performing a Tensilon test if myasthenic syndrome is suspected.

Measure the child’s electrolytes, CPK, lactate, pyruvate, carnitine, and/or other biochemical markers:

Measure the child’s electrolytes, CPK, lactate, pyruvate, carnitine, and/or other biochemical markers:

• If CPK/EMG results are normal, conduct a DNA test for Prader-Willi syndrome.

• If CPK concentration is more than 10 times the upper limit of normal, EMG is not crucial. Perform DNA tests for fukutin-related protein (FKRP) gene mutations, and/or other muscular dystrophies. Consder brain imaging (MRI). If DNA testing results are negative, conduct a muscle biopsy.

• If CPK is elevated less than 10 times the upper limit of normal, conduct EMG. If the electromyogram findings indicate neurogenic changes, order genetic testing for survival motor neuron (SMN) gene or Charcot-Marie-Tooth/Dejerine-Sottas disease. An electromyogram showing decrement or facilitation indicates a neuromuscular junction defect. If the electromyographic findings are normal or indicate myopathy, conduct a muscle biopsy (EMG findings may be normal in certain myopathies).

111. What are four characteristics of damage to the anterior horn cell?

Fasciculations (most easily observed on the tongue in the neonate)

Fasciculations (most easily observed on the tongue in the neonate)

Atrophy (difficult to see in the newborn because of adipose tissue surrounding almost all muscles)

Atrophy (difficult to see in the newborn because of adipose tissue surrounding almost all muscles)

112. Why is myotonic dystrophy an example of the phenomenon of “anticipation”?

1Prechtl HFR. Continuity of neonatal function from prenatal to postnatal life. Oxford, England: Spastics International Medical; 1984.

2The New Ballard Score. Scarf sign. <http://www.ballardscore.com/Pages/mono_neuro_scarf.aspx>; 2013 [accessed 17.06.13].

3Ricci D, Cesarini L, Groppo M, et al. Early assessment of visual function in full term newborns. Early Hum Dev 2008;84(2):107–113.

4Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K, et al. New Ballard Score, expanded to include premature infants. J Pediatr 1991;119:417–23.

5Dubowitz L, Ricci D, Mercuri E. The Dubowitz neurological examination of the full-term newborn. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2005;11:52–60.

6Di Capua M, Fusco L, Ricci S, et al. Benign neonatal sleep myoclonus: clinical features and video-polygraphic recordings. Mov Disord 1993;8(2):191–4.

7Laux L, Nordli D Jr. Neonatal nonepileptic events. In: Kaplan PW, Fisher RS, editors. Imitators of epilepsy. 2nd ed. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2005.

8Clancy R. Imitators of epileptic seizures specific to neonates and infants. In: Panayiotopoulos CP, editor. The atlas of epilepsies. London: Springer; 2010.

9Malessy MJ, Pondaag W. Obstetric brachial plexus injuries. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2009;20(1):1–14.

10Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, et al. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med 2011;364(11):993–1004.

11Fobe JL, Rizzo AM, Silva IM. IQ in hydrocephalus and meningomyelocele: implications of surgical treatment. Arch Neuropsychiatr 1999;57:44–50.

12Patterson MC. Holoprosencephaly: the face predicts the brain—the image predicts its function. Neurology 2002;59:1833–1834.

13Heuer GG, Gabel B, Beslow LA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of vein of Galen aneurysmal malformations. Childs Nerv Syst 2010;26:879–887.

14Hurwitz S. Neurofibromatosis. Clinical pediatric dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993. p. 624–629.

15National NF Foundation. < http://www.nf.org>; [accessed 24.08.12].

16DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics 2000;105:608–614.

17The Sturge-Weber Foundation. < http://www.sturge-weber.com>; [accessed 24.08.12].

18Porksen G, Pfeiffer C, Hahn G, et al. Neonatal seizures in two sisters with incontinentia pigmenti. Neuropediatrics 2004 Apr;35(2):139–42.

19Gupta SN, Kechi AM, Kanamalla US. Intracranial hemorrhage in term newborns: management and outcomes. Pediatr Neurol 2009;40(1):1–12.

20Tavani F, Zimmerman RA, Clancy RR, et al. Incidental intracranial hemorrhage after uncomplicated birth: MRI before and after neonatal heart surgery. Neuroradiology 2003;45(4):253–8.

21Volpe JJ, editor. Neurology of the newborn. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

22de Vries LS, Liem KD, van Dikj K, et al. Early versus late treatment of posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: results of a retrospective study from five neonatal studies in the Netherlands. Acta Pediatr 2002;91:212–7.

23Fulmer BB, Grabb PA, Oakew WJ, et al. Neonatal ventriculosubgaleal shunts. Neurosurgery 2000;47:80–4.

24Kennedy CR, Ayers S, Campbell MJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of acetazolamide and furosemide in posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation in infancy: follow-up at 1 year. Pediatrics 2001;108:569–607.

25Hack M, Flannery DJ, Schluchter M, et al. Outcomes in young, very low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 2002;346:149–57.

26Ment LR, Vohr B, Allan W. Change in cognitive function over time in very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA 2003;289:705–11.

27Roland EH, Hill A. Germinal matrix-intraventricular hemorrhage in the premature newborn: management and outcome. Neurol Clin 2003;21:833–51.

28O’Shea MT, Allred EN, Kuban KC, et al. Intraventricular hemorrage and developmental outcomes at 24 months of age in extremely preterm infants. J Child Neurol 2012;27:22–9.

29Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Laner J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity—moving beyond gestational age. New Engl J Med 2008;358:1672–81.

30Morse SB, Zheng H, Tang Y, et al. Early school-age outcomes of late preterm infants. Pediatrics 2009;123:e622–e629.

31Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, et al. EPICure Study Group: Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med 2005;352:9–19.

32Volpe JJ. Cerebral white matter injury of the premature infant: more common than you think. Pediatrics 2003;112:176–80.

33O Khwaja, JJ Volpe. Pathogenesis of cerebral white matter injury of prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Edition 2008;93(2):F153–F161.

34Counsell SJ, Allsop JM, Harrison MC. Diffusion weighted imaging of the brain in preterm infants with focal and diffuse white matter abnormality. Pediatrics 2003;112:1–7.

35American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Academy of Pediatrics, editors. Neonatal encephalopathy and cerebral palsy: defining the pathogenesis and pathophysiology. Washington, DC: ACOG and AAP; 2003.

36Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, et al. Antepartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Austrialian case-control study. BMJ 1998;317(7172):1549–53.

37Becher JC, Bell JE, Keeling JW, et al. The Scottish perinatal neuropathology study: clinicopathological correlation in early neonatal deaths. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2004;89:F399–F407.

38Phelan JP, Ahn MO. Perinatal observations in forty-eight neurologically impaired infants. Am J Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;171(2):424–31.

39Bonifacio SI, Glass HC, Vanderpluym J, et al. Perinatal events and magnetic resonance imaging in therapeutic hypothermia. J Pediatr 2011;158:360–5.

40Shellhaas RA, Chang T, Tsuchida T, et al. The American Clincial Neurophysiology Society’s guideline on continuous electroencephalography monitoring in neonates. J Clin Neurophys 2011;28(6):611–7.

41Roland EH, Poskitt K, Rodriguez E, et al. Perinatal hypoxic-ischemic thalamic injury: clinical features and neuroimaging. Ann Neurol 1998;44:161–6.

42Pasternak JF, Gorey MT. The syndrome of acute near-total intrauterine asphyxia in the term infant. Pediatr Neurol 1998;18:391–8.

43Myers RE. Two patterns of perinatal brain damage and their conditions of occurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972;112:246–76.

44Eklind S, Mallard C, Leverin A, et al. Bacterial endotoxin sensitizes the immature brain to hypoxic-ischemic injury. Eur J Neurosci 2001;13:1101–6.

45Rutherford M, Ward P, Allsop J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in neonatal encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev 2005;81:13–25.

46Nash KB, Bonifacio SL, Glass HC, et al. Video-EEG monitoring in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia. Neurology 2011;76:556–82.

47Barkovich AJ, Baranski K, Vigneron D, et al. Proton MR spectroscopy for the evaluation of brain injury in asphyxiated, term neonates. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1399–1405.

48Hunt RW, Neil JJ, Coleman LT, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient in the posterior limb of the internal capsule predicts outcome after perinatal asphyxia. Pediatrics 2004;114:999–1003.

49Wolf RL, Haselgrove JH, Clancy RR, et al. Quantitative apparent diffusion coefficient measurements in term neonates for early detection of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: initial experience. Radiology 2001;218:825–33.

50Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2005;365:663–70.

51Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2005;353(15):1574–84.

52Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2009;361(14):1349–58.

53Hypothermia and other treatment options for neonatal encephalopathy: an executive summary of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Workshop. J Pediatr 2011;159(5):851–8.

54AD Edwards, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ 2010;340:c363.

55Cowan FM, Pennock JM, Hanrahan JD, et al. Early detection of cerebral infarction and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in neonates using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropediatrics 1994;25:172–5.

56Nelson KB, Lynch KB. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:150–6.

57Lynch JK, Nelson KB Epidemiology of perinatal stroke. Curr Opin Pediatr 2001;13:499–505.

58Mercuri E, Rutherford M, Cowan F, et al. Early prognostic indicators of outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction: a clinical, electroencephalogram, and magnetic resonance imaging study. Pediatrics 1999;103:39–46.

59Wu YW, Miller SP, Chin K, et al. Multiple risk factors in neonatal sinovenous thrombosis. Neurology 2002;3:438–40.

60Kersbergen KJ, Groenendaal F, Benders MJNL, de Vries LS. Neonatal cerebral sinovenous thrombosis: neuroimaging and long-term follow-up. J Child Neurol 2011;26:1111–20.

61Florieke JB, Kersbergen KJ, van Ommen CH, et al. Neonatal cerebral sinovenous thrombosis from symptom to outcome. Stroke 2010;41:1382–8.

62Moharir MD, Shroff M, Pontigon AM, et al. A prospective outcome study of neonatal cerebral sinovenous thrombosis. J Child Neruol 2011;26:1137–44.

63United Cerebral Palsy. < http://www.ucp.org>; [accessed 27.08.12].

64Neufeld MD, Frigon C, Graham AS, et al. Maternal infection and risk of cerebral palsy in term and preterm infants. J Perinatol 2005;2:108–13.

65Wu YW, Escobar GJ, Grether JK, et al. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. JAMA 2003;290:2677–84.

66Hagberg H, Mallard C, Jacobsson B. Role of cytokines in preterm labour and brain injury. BJOG 2005;112(Suppl 1):16–8.

67Yoon BH, Park CW, Chaiworapongsa T. Intrauterine infection and the development of cerebral palsy. BJOG 2003;110(Suppl 20):124–7.

68Murray DM, Boylan GB, Ali I, et al. Defining the gap between electrographic seizure burden, clinical expression, and staff recognition of neonatal seizures. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008;93:F187–191.

69Shah DK, Mackay MT, Lavery S, et al. Accuracy of bedside electroencephalographic monitoring in comparison with simultaneous continuous conventional electroencephalography for seizure detection in term infants. Pediatrics 2008;121(6):1146–54.

70Pearl PL. New treatment paradigms in the metabolic epilepsies. J Inherit Metab Dis 2009;32(2):204–13.

71Deprez L, Weckhuysen S, Holmgren P. Clinical spectrum of early-onset epileptic encephalopathies associated with STXBP1 mutations. Neurology 2010;75:1159–65.

72Yamamoto H, Okumura A, Fukuda M. Epilepsies and epileptic syndromes starting in the neonatal period. Brain Dev 2011;33:213–20.

73Ficicioglu C, Bearden D. Isolated neonatal seizures: when to suspect inborn errors of metabolism. Pediatr Neurol 2011 Nov;45(5):283–91.

74Berkovic SF, Heron SE, Giordano L, et al. Benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures: characterization of a new sodium channelopathy. Ann Neurol 2004;55:550–7.

75Painter MJ, Scher MS, Stein AD, et al. Phenobarbital compared with phenytoin for the treatment of neonatal seizures. N Engl J Med 1999;341:485–9.

76Clancy, RR. Summary proceedings from the neurology group on neonatal seizures. Pediatrics 2006;117:S23–S27.