Chapter 49A Neurological Complications of Systemic Disease*

Adults

Cardiac Disorders and the Nervous System

Cardiogenic Embolism

Cardiogenic emboli are most prevalent in patients with atrial fibrillation with or without mitral stenosis, intramural thrombi, prosthetic cardiac valves, infective endocarditis, atrial flutter, and sick sinus syndrome. Other causes include recent myocardial infarction (MI), left atrial thrombus or turbulence, atrial myxoma, mitral annulus calcification and prolapse, hypokinetic left ventricular segments, and dilated cardiomyopathy. (Chapter 49B discusses emboli from congenital heart disease, a consideration in young people with either valvular heart disease or mitral valve prolapse.)

Transesophageal echocardiography is an appropriate method to investigate people younger than 55 years of age with suspected cardiogenic emboli who may need anticoagulation or surgery and in those with no clear source demonstrated on transthoracic echocardiography when suspicion for embolic source is high. Some have suggested that transesophageal echocardiography is appropriate in all patients with cryptogenic stroke (de Bruijn et al., 2006).

Anticoagulation has established benefit in reducing the risk of stroke in persons with atrial fibrillation. Consensus supports the use of long-term oral warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation in most cases. Risk stratification systems are helpful in deciding whether anticoagulation is warranted (Gage et al., 2001). Aspirin (325 mg/day) is the recommended agent when warfarin is contraindicated. Recent studies suggest that addition of clopidogrel (75 mg/day) is also worthwhile (Connolly et al., 2009). Standard practice is to start warfarin at least 3 weeks before elective cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation of more than 2 days’ duration. Warfarin therapy is continued at least until a normal rhythm has been maintained for 4 weeks. Myocardial infarcts, especially apical, anterolateral, or large infarcts, carry a risk of embolic stroke. In most cases, infarction occurs within a week, but the risk persists for approximately 2 months. Therefore, it is recommended to use heparin for those patients not on thrombolytic therapy after MI, and to continue warfarin for 3 months if they have an increased risk of embolism. The groups with increased risk are those with congestive heart failure, previous emboli, a mural thrombus, left ventricular dysfunction, substantial wall motion abnormalities, or atrial fibrillation.

Syncope

Transitory global cerebral ischemia secondary to cardiac arrhythmia often causes syncope. Most normal people have fainted at least once. Nonspecific premonitory symptoms such as visual disturbances, paresthesias, and lightheadedness may precede the syncope (Soteriades et al., 2002). Syncope usually is associated with loss of muscle tone, but prolonged ischemia causes tonic posturing and irregular jerking movements that are easily mistaken for seizures (Stokes-Adams attacks). The syncopal patient is pale, and postictal confusion is absent or short lived, usually lasting less than 30 seconds. Obstructed outflow from aortic stenosis or left atrial tumor or thrombus is one cardiac cause of syncope. Other causes are arrhythmias, especially from ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, chronic sinoatrial disorder or sick sinus syndrome, and paroxysmal tachycardia. Placement of implantable loop recorders allows the recording of electrocardiographic data during spontaneous syncopal events. This strategy increases the diagnostic rate and permits appropriate treatment to be instituted (Farwell et al., 2006). Arrhythmia is detectable in 25% to 46% of patients with syncope, and another 24% to 42% will be in sinus rhythm during a clinical event, which is therefore not attributable to a disturbance of cardiac rhythm (McKeon et al., 2006). Additional causes of syncope are central and peripheral dysautonomias, postural hypotension, and endocrine and metabolic disorders. (Discussions of vasovagal syncope and the prolonged QT-interval syndrome are in Chapter 49B.)

Cardiac Arrest

In the mature brain, gray matter generally is more sensitive to ischemia than white matter, and the cerebral cortex is more sensitive than the brainstem. (The premature brain has the reverse pattern of sensitivity; see Chapter 60.) Cerebral or spinal regions lying between the territories supplied by the major arteries (watershed areas) are especially vulnerable to ischemic injury.

Prolonged cardiac arrest causes widespread and irreversible brain damage characterized by prolonged coma leading to a persistent vegetative state. Prolonged coma and loss of brainstem reflexes indicate a poor prognosis for survival or useful recovery. Therapeutic hypothermia initiated rapidly after the arrest improves neurological outcome (Bernard et al., 2002). Absence of the pupillary response to light and absence of motor recovery better than extensor posturing at 72 hours are perhaps the most useful clinical guides to prognosis (see Chapter 5 for further discussion). These features of the clinical examination, along with measurement of neuron-specific enolase and recording of median-derived somatosensory evoked potentials (to determine whether the N20 component is absent bilaterally), can be helpful in prognostication, although recent data question whether these same tests and time frames apply in patients treated with hypothermia (Rossetti et al., 2010).

Complications of Cardiac Catheterization and Surgery

Hypoxia and emboli are the usual causes of “post-pump” encephalopathy, seizures, and cerebral infarction after cardiac surgery. Type of surgery, symptomatic cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and advanced age are important risk factors for neurological complications (Boeken et al., 2005). Ascertaining the degree of functionally significant cerebrovascular disease is an essential part of the preoperative evaluation (McKhann et al., 2006). The causes of postoperative psychoses or encephalopathy are metabolic disturbances, medication, infection, and multiorgan failure. Intracranial infection should be suspected when behavioral disturbances develop several weeks postoperatively in patients receiving immunosuppressive agents. The usual causes of postoperative seizures are focal or generalized cerebral ischemia, electrolyte or metabolic disturbances, and multiorgan failure. Intracranial hemorrhage is a rare complication of cardiopulmonary bypass. Cognitive changes after cardiac bypass surgery are detectable in 53% of patients at discharge, some of which persist. However, the previously described late cognitive decline that occurs years following cardiac bypass surgery is similar to that found in age-matched patients with coronary artery disease managed without surgery (Selnes et al., 2008). Compression or traction injuries to the brachial plexus, especially the lower trunk, and the phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerves may occur during cardiac surgery. Other common early complications of cardiac transplantation are organ rejection followed by cardiac failure and the side effects of immunosuppressive drugs. Cerebral air embolism may require hyperbaric oxygen therapy combined with aggressive resuscitation (Hinkle et al., 2001). Infection (meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or cerebral abscess) secondary to immunosuppressive therapy is the most important late complication. The infecting organisms include Aspergillus, Toxoplasma, Cryptococcus, Candida, Nocardia, and viruses including JC virus. An increased risk of lymphoma and reticulum cell sarcoma has been observed in patients on long-term immunosuppressive agents. Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma may be difficult to distinguish clinically or radiologically from infection, and biopsy may be necessary (see Chapters 33A and 52C).

Stroke occurs in approximately 5% of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. The risk is increasing because of the increasing number of procedures in older patients with more severe vascular disease, and in complicated combined procedures such as bypass surgery plus valve replacement (Nussmeier, 2002). Other risk factors include proximal aortic atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes, and female gender. The mechanism is either embolic or, less commonly, a watershed infarction from hypoperfusion. A history of previous stroke also increases the risk, but a carotid bruit or radiological evidence of atherosclerotic disease of the carotid artery does not. Carotid endarterectomy preceding cardiac surgery is not justified.

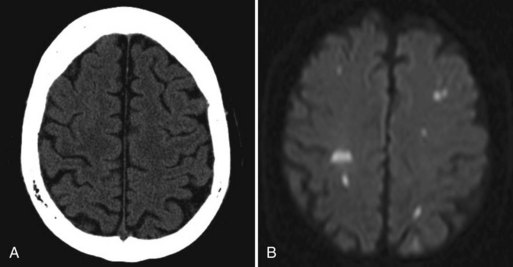

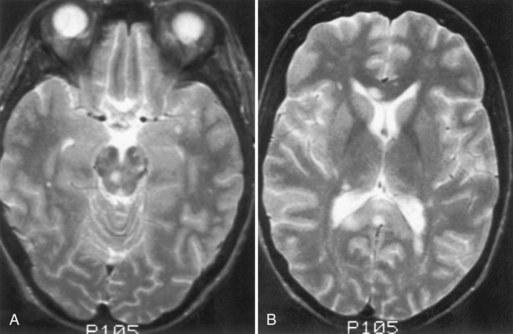

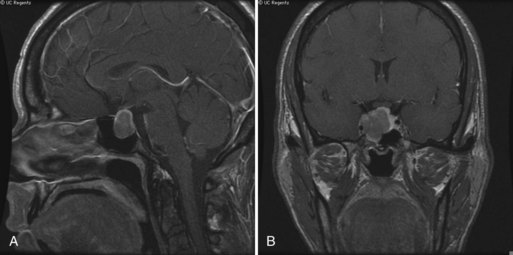

A few patients who fail to recover consciousness after surgery, despite the absence of any metabolic cause, probably have suffered diffuse cerebral ischemia or hypoxia. Hemispheric or multifocal infarction (Fig. 49A.1) is responsible in some cases. In evaluating patients with postoperative neurological deficits, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than CT to ischemic change and may reveal multiple small embolic infarcts (Wityk et al., 2001).

Infective Endocarditis

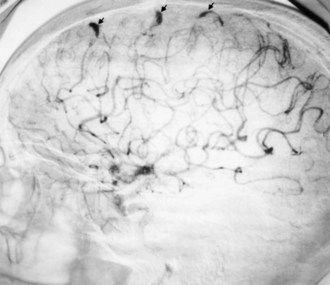

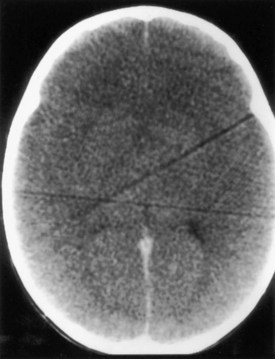

Cerebral mycotic aneurysms (Fig. 49A.2) are recognized complications of infective endocarditis and may result in intracranial hemorrhage. They are generally more distally located than congenital berry aneurysms. The pathogenesis of mycotic aneurysms is unclear. The most likely cause is impaction of infected material in the vasa vasorum, with resulting destruction of the wall of an artery. Intraluminal occlusion of the vessel by infected material, with subsequent aneurysmal formation, is less likely but has been documented in some cases. Mycotic aneurysms may be clinically silent and sometimes resolve with antibiotic therapy. They are less common but occur earlier in acute than in subacute bacterial endocarditis. Their natural history is unknown.

Antibiotic therapy to resolve the cardiac infection is the mainstay of treatment and is important in preventing neurological complications (Heiro et al., 2000). Neurological abnormalities usually resolve. Patients with progressive or persistent neurological deficits or abnormalities on CSF examination require imaging studies. MRI findings suggestive of mycotic aneurysm necessitate arteriography. Once mycotic aneurysms have ruptured, curative surgical or endovascular treatment is necessary to prevent re-rupture. Management of unruptured mycotic aneurysms is less clear, and many advocate conservative management with antibiotics and serial imaging. Anticoagulants are usually withheld from patients with infective endocarditis and cerebral embolism until after appropriate antibiotic therapy, owing to the risk of rupture of an unrecognized mycotic aneurysm. Anticoagulation also may increase the risk of hemorrhagic transformation of embolic infarcts.

Diseases of the Aorta

Aortitis

The causes of aortitis include syphilis, Takayasu disease, irradiation, transient emboligenic aortoarteritis, rheumatic fever, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, and several connective tissue diseases. The latter group includes giant cell arteritis (see Chapter 69), rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and scleroderma. Neurological complications occur when arteries that perfuse neural tissues are involved, or in relation to a secondary aortic pathological process or lesion such as an aneurysm.

Takayasu disease (pulseless disease) is primarily a disease of young women. Nonspecific symptoms are fever, weight loss, myalgias, and arthralgia. Obstruction of major vessels of the aortic arch causes loss of pulses in the neck and arms, hypertension, and aortic regurgitation. Less common signs and symptoms are headache, seizures, transient cerebral ischemic attacks, and stroke. The diagnosis is established by the clinical features, and corticosteroids are the treatment of choice. Despite the severe vascular involvement, the clinical neurological course is often good in patients who receive appropriate treatment (Ringleb et al., 2005).

Complications of Aortic Surgery

Spinal cord infarction remains the most serious neurological complication of aortic surgery. CSF drainage and distal aortic perfusion may be important adjuncts to corrective surgery for thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms, significantly reducing the incidence of paraplegia and paraparesis (Hnath et al., 2008). Other complications are neuropathy, radiculopathy, post-sympathectomy neuralgia after surgical division of the sympathetic chain, and disturbances of penile erection or ejaculation with surgical division of the superior hypogastric plexus (Dougherty and Calligaro, 2001).

Connective Tissue Diseases and Vasculitides

The cause of vasculitic neuropathy is nerve infarction from occlusion of the vasa nervorum. A mononeuropathy multiplex develops that becomes increasingly confluent with increasing nerve involvement until it resembles a distal symmetrical polyneuropathy. Nerves in watershed regions that lie between different vascular territories, such as the mid-thigh or mid- to upper arm, are more likely to be involved. Both large and small fibers are affected. Treatment with corticosteroids, often in conjunction with other immunosuppressive therapy, usually is effective (Burns et al., 2007), but intravenous immunoglobulin may be helpful in resistant cases (Levy et al., 2005).

Polyarteritis Nodosa, Churg-Strauss Syndrome, and Overlap Syndrome

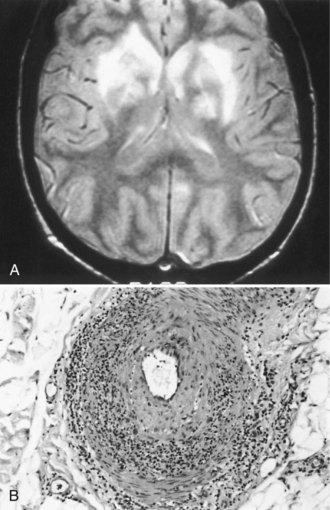

CNS involvement usually occurs later than peripheral involvement in the course of the disease. Common features are headache, which sometimes indicates aseptic meningitis, and behavioral disturbances such as cognitive decline, acute confusion, and affective or psychotic disorders. The electroencephalogram (EEG) sometimes shows diffuse slowing, but neuroimaging studies are generally normal. Focal CNS deficits are uncommon but are typically sudden in onset and may be caused by cerebral infarction (Fig. 49A.3) or hemorrhage. Angiography may not show the underlying vasculitis. Ischemic or compressive myelopathies from extradural hematomas are rare complications.

Isolated Angiitis of the Nervous System

The description of isolated angiitis (granulomatous angiitis) of the CNS is in Chapter 51E, and that of the PNS is discussed in Chapter 76.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common connective tissue disease. Discussion of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is in Chapter 49B. Systemic vasculitis occurs in up to 25% of adult patients, but CNS involvement is rare. Pathological involvement of the cervical spine (Fig. 49A.4) or atlantoaxial dislocation may cause a myelopathy, headaches, or hydrocephalus or lead to brainstem and cranial nerve signs from compression or vertebral artery involvement. Special care with maneuvers requiring hyperextension of the neck, such as endotracheal intubation, is essential in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Surgical fixation of subluxation usually is unnecessary unless displacement is marked or an associated myelopathy is severe or progressive. The risk of a fatal outcome with a minor whiplash injury is a consideration.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The most common neurological manifestations are episodic affective or psychotic disorders that may be difficult to distinguish from corticosteroid-induced mental changes. Cognitive dysfunction often is temporary. The clinical and imaging features may mimic those of multiple sclerosis (Theodoridou and Settas, 2006). Treatment is empirical, depending on presentation and the probable underlying pathophysiology. Disturbances of consciousness sometimes occur, especially in patients with systemic infections. Focal neurological deficits may result from stroke. The pathogenesis of stroke in SLE includes cardiac valvular disease, thrombosis associated with antiphospholipid antibodies, and less commonly, cerebral vasculitis. Anticoagulant therapy may prevent stroke recurrence in patients with the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Dyskinesias, especially chorea, occur in some patients with SLE, but underlying structural pathology of the basal ganglia is rare; chorea is associated with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. The probable causes of generalized or partial seizures are microinfarcts, metabolic disturbances, and systemic infections. (Chapter 49B discusses the pediatric aspects of SLE).

PNS involvement occurs less often and usually is characterized by a distal sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy (Rosenbaum, 2001) that sometimes is subclinical but can be detected by sensory threshold testing; it is related to reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density (Tseng et al., 2006). Other forms of neuropathy include an acute or chronic demyelinating polyneuropathy that resembles Guillain-Barré syndrome or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, single or multiple mononeuropathies, and optic neuropathy. Corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis are beneficial in treating neuropathies caused by necrotizing vasculitis but have less certain value in other circumstances.

Sjögren Syndrome

Polyneuropathy is the most common peripheral manifestation, but mononeuropathy multiplex also may occur (Goransson et al., 2006). Sensory neuronopathy is unusual but is more characteristic of Sjögren syndrome than other connective tissue diseases (Rosenbaum, 2001).

Behçet Disease

The combination of uveitis and oral and genital ulcers defines Behçet disease, a disorder of unknown cause. Aseptic meningitis or meningoencephalitis occurs in 20% of cases. Other findings may include focal or multifocal neurological signs caused by ischemic disease of the brain or spinal cord, related to small venous inflammatory disease; the brainstem is frequently involved. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is another possible complication (Siva and Fresko, 2000). The CSF commonly shows a mild pleocytosis, and the protein concentration may be increased. Peripheral nerve involvement is rare and takes the form of polyneuropathy or mononeuropathy multiplex. Treatment is with corticosteroids. Anticoagulation is used to treat cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (see Chapter 51A).

Respiratory Diseases

Hypoxia

Sleep apnea syndromes cause chronic nocturnal hypoxia and become symptomatic as excessive daytime sleepiness. Many affected patients are obese and plethoric and snore heavily. Chapter 68 summarizes treatment.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

Encephalopathies complicate sepsis and most often occur in patients with respiratory distress syndrome. The pathogenesis is multifactorial and relates to reduced cerebral blood flow, cerebral edema, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, direct cerebral infection, toxins produced by infecting organisms, metabolic abnormalities, and the effects of medication (Papadopoulos et al., 2000). The encephalopathy tends to fluctuate in severity, is often worse at night, and may be associated with marked EEG abnormalities. Treatment is the correction of factors responsible for the underlying sepsis; no specific treatment exists for the encephalopathy.

Sarcoidosis

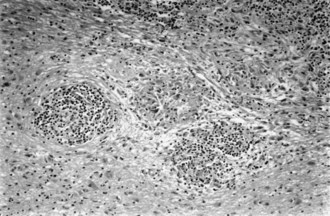

Sarcoidosis, a disorder of unknown cause, involves many organ systems and has many different clinical presentations. It is more common in people of African descent than in whites and in women than in men. Often, discovery of the disease is incidental on routine chest x-ray examination. The prevalence of neurological involvement in any series varies with case selection and diagnostic criteria but may be as high as 5%. The nervous system may be involved directly by the disease, or involvement may be secondary to opportunistic infections associated with abnormalities of the immune system. The following discussion considers only direct involvement (Fig. 49A.5).

Neurosarcoidosis often remits spontaneously, but progressive neurological disease occurs in approximately 30% of cases. The diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis is difficult in the absence of systemic disease, especially cutaneous or pulmonary involvement. Whole-body CT or positron emission tomography (PET) scans may identify subclinical systemic tissue involvement. Histological confirmation often requires biopsy of seemingly unaffected tissue (e.g., muscle or conjunctiva) if other lesions are not accessible. Neither the tuberculin skin test nor the blood concentration of angiotensin-converting enzyme definitively establishes the diagnosis. The recommended treatment is with corticosteroids, but its long-term value is not established. The initial dose of prednisone is 1 mg/kg/day, which is adjusted according to clinical response. Irradiation of a focal lesion is beneficial in some cases. Refractory cases of neurosarcoidosis may respond to a variety of immunosuppressive agents including cyclophosphamide and infliximab (Santos et al., 2010). Useful surgical measures are the excision of focal enlarging granulomas and the placement of a shunt to relieve hydrocephalus.

Hematological Disorders with Anemia

Megaloblastic Anemia

Vitamin B12 deficiency causes myelopathy, encephalopathy, optic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, or some combination of these disorders. The neurological complications do not necessarily correlate with the presence or severity of associated megaloblastic anemia. Folic acid masks the anemia without preventing the neurological complications. Nitrous oxide anesthesia may unmask a subclinical cobalamin deficiency (Marie et al., 2000). Folic acid fortification of the grain supply in the United States began in 1994 to prevent spina bifida; consequently, anemia is no longer a reliable marker of vitamin B12 deficiency. Increased levels of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid may indicate intracellular B12 deficiency even in the setting of normal serum B12 levels.

Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell disease, the result of a genetic point mutation in the beta-globin gene, causes a vasculopathy of both large and small vessels (Prengler et al., 2002). Sickled cells adhere to the vascular endothelium, and a cascade of activated inflammatory cells and clotting factors leads to a nidus for thrombus formation. Hypoxia, infection, inflammation, dehydration, and acidosis increase sickling.

Proliferative Hematological Disorders

Leukemias

Infection is a common complication of chemotherapy or corticosteroid therapy. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics often encourages infection by unusual organisms. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is an uncommon complication of leukemia (see Chapter 53B).

Plasma Cell Dyscrasias

The basis for the classification of plasma cell dyscrasias is the protein synthesized. Complicating these disorders are paraneoplastic syndromes (see Chapter 52G) and an increased susceptibility to CNS infections.

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis may occur as a familial disorder with dominant inheritance. Portuguese, Japanese, Swedish, and other varieties occur. The main neurological complication is a small-fiber sensory neuropathy with marked impairment of pain and temperature appreciation and lesser involvement of other sensory modalities (see Chapter 76). An associated dysautonomia is conspicuous. Weakness develops later.

Both primary and secondary nonfamilial amyloidosis occur. Primary amyloidosis occurs in the absence of other disorders (except multiple myeloma), whereas secondary amyloidosis occurs in association with such disorders as chronic infection. Peripheral neuropathy is a common feature of primary but not secondary amyloidosis. Characteristic of the neuropathy is a progressive sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy with autonomic involvement or carpal tunnel syndrome. Cranial neuropathy is uncommon; cranial nerves III, V, and VII are most often affected. Cardiovascular and renal dysfunction is common, and other organ systems may be involved. The clinical features and presence (in most cases) of a monoclonal protein in the serum suggests the diagnosis. A variety of treatments are available, many with limited success (Rajkumar and Gertz, 2007). Death usually results from systemic complications.

Lymphoma

Neurological complications of lymphoma can be due to direct spread of tumor, compression of the nervous system by extrinsic tumor, and paraneoplastic syndromes (see Chapter 52G).They also may result from irradiation or chemotherapy, thrombocytopenic hemorrhage, or opportunistic infections. Primary CNS lymphoma is a known complication of immunosuppression and occurs most often in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (see Chapter 53A) and less frequently in transplant recipients.

Hemorrhagic Diseases

Other Hemorrhagic Disorders

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is a disorder of uncertain cause, possibly immune-mediated, that often has a fatal outcome. It sometimes is associated with the use of certain medications, especially quinine (Kojouri et al., 2001). The clinical features are thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia, fever, neurological abnormalities, and renal disease. The neurological features may include headache, mental changes, altered state of consciousness, seizures, and focal deficits. MRI may reveal infarctions or white matter abnormalities. Treatment options are plasma exchange or high-dose intravenous gamma globulin infusions, splenectomy, and administration of corticosteroids or antiplatelet agents. Rapid administration of platelets may cause death.

Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndromes

Antiphospholipid antibodies (the lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies) are detectable in several disorders, but especially in SLE, Sneddon syndrome (Fig. 49A.6), and other connective tissue disorders (Cervera et al., 2002). These antibodies occur in patients taking certain medications (e.g., phenothiazines, phenytoin, propranolol, amoxicillin), with some infections and obstetrical complications, and as an incidental finding in healthy people. The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies increases the risk of thrombotic disease. The cause of cerebral ischemia is either arterial or venous occlusion. Visual abnormalities include amaurosis fugax and ischemic optic neuropathy or retinopathy. The occurrence of migraine-like headaches may be fortuitous. An acute ischemic encephalopathy characterized by confusion, obtundation, quadriparesis, and bilateral pyramidal signs may occur. Dementia, chorea, transient global amnesia, transverse myelopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and seizures are other possible manifestations. The condition may simulate multiple sclerosis clinically and on MRI (Cuadrado et al., 2000).

Liver Disease

In patients with acute hepatic failure, the development of severe cerebral edema is common (Fig. 49A.7). Several other neurological manifestations occur with chronic hepatic disorders.

Portal-Systemic Encephalopathy

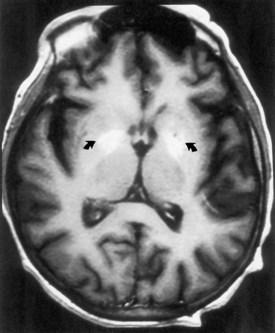

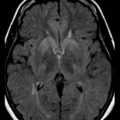

Chronic liver disease causes a portal-systemic encephalopathy characterized by an abnormal mental status. Points to emphasize are that (1) the encephalopathy may have an insidious onset, delaying its clinical recognition and treatment, (2) a flapping tremor (asterixis) may be the only other neurological sign, and (3) liver function test results, other than the fasting arterial ammonia concentration, do not always correlate with the severity of the clinical disturbance. Focal neurological signs may be present but have no prognostic significance (Cadranel et al., 2001). EEG abnormalities also correlate with the severity of encephalopathy. MRI may show abnormal signal intensity in the basal ganglia on T1-weighted images (Fig. 49A.8). The mechanism of the encephalopathy is unknown. Treatment is discussed in Chapter 56.

Chronic Non-Wilsonian Hepatocerebral Degeneration

In some patients with chronic liver disease, a permanent neurological deficit develops, even in the absence of previous portal systemic encephalopathy. The neurological features are similar to those of Wilson disease (see Chapter 71): intention tremor, ataxia, dysarthria, and choreoathetosis are common. As with portal systemic encephalopathy, the severity of the neurological disorder correlates best with the fasting arterial ammonia level. Neuroimaging findings may be abnormal. Specific treatment is not available.

Gastrointestinal Diseases

Nutritional deficiency is the usual cause of neurological complications of GI disorders (see Chapter 57). Several different dietary components are simultaneously deficient, and a single responsible nutrient is rarely defined.

Gastric Surgery

Neurological complications occur in 10% to 15% of patients after gastric resection. Because of the loss of gastric intrinsic factor, impaired vitamin B12 absorption may be responsible in part for neuropathy or myelopathy (Chaudhry et al., 2002). Postgastrectomy neuropathy, however, does not usually respond to vitamin B12 replacement alone. The myopathy that sometimes occurs probably is caused by vitamin D deficiency.

Celiac Disease

Chronic gluten enteropathy may cause a progressive and sometimes fatal CNS disorder that includes some combination of encephalopathy, myelopathy, and cerebellar disturbance. Peripheral neuropathy may be an associated, relatively underrecognized, finding (Hadjivassiliou et al., 2006). An axonal neuropathy also occurs alone and without a measurable vitamin deficiency; restriction of dietary gluten leads to gradual resolution of neuropathic symptoms.

Whipple Disease

Whipple disease is a multisystem disorder caused by infection with the bacillus Tropheryma whippelii. The clinical features are steatorrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and a variety of systemic complaints. Neurological involvement is rare but may occur in the absence of GI symptoms. The most common neurological feature is dementia (Manzel et al., 2000). Less common are cerebellar ataxia, seizures, myoclonus, clouding of consciousness, visual disturbances, papilledema, supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, myelopathy, and hypothalamic dysfunction. A characteristic movement disorder, oculomasticatory myorhythmia, is peculiar to Whipple disease; pendular vergence oscillations of the eyes, with concurrent contractions of the masticatory muscles, occur and persist during sleep. Oculofacial-skeletal myorhythmia also is pathognomonic. When present, it resembles oculomasticatory myorhythmia but also involves nonfacial muscles. Postmortem examination shows abnormalities of the gray matter of the hypothalamus, cingulate gyrus, basal ganglia, insular cortex, and cerebellum.

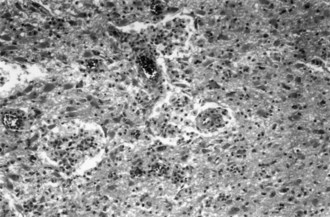

Small-intestine biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Patients with neurological involvement also show cells that stain positively with periodic acid–Schiff stain in the CSF and brain parenchyma (Fig. 49A.9). Polymerase chain reaction analysis of intestinal tissue or CSF sometimes is helpful. Treatment is prolonged, with antibiotic drugs such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, penicillin, tetracycline, or erythromycin. Patients who have a compatible clinical syndrome should receive treatment even when the biopsy result is negative.

Renal Failure

Overview of Related Neurological Complications

Renal failure is associated with several neurological manifestations. Uremic encephalopathy is discussed in Chapter 56. Its clinical features resemble those of other metabolic encephalopathies, and its severity does not correlate well with any single laboratory abnormality. The mechanism of encephalopathy is not established but has been attributed to accumulation of toxic organic acids in the CNS or to direct toxic effects on the CNS of parathyroid hormone. It may be associated with asterixis and myoclonus. Characteristics of so-called twitch-convulsive syndrome are asterixis and myoclonic jerks accompanied by fasciculations, muscle twitches, and seizures (Brouns and De Deyn, 2004). Chorea may result from basal ganglia dysfunction. Stroke incidence increases in chronic renal failure. Ischemic stroke may relate to atherosclerosis, thromboembolic disease, or hypotension during dialysis. Atherosclerosis generally is more diffuse than in the age-matched general population, probably because of a combination of traditional risk factors and factors related to the renal failure, such as the accumulation of endogenous guanidino compounds. Hyperhomocysteinemia also is common; this condition, of uncertain etiology, may predispose affected persons to ischemic stroke and responds to enhanced dialysis over superflux membranes (Brouns and De Deyn, 2004). The incidence of intracranial hemorrhage is increased; hypertension, polycystic kidney disease, uremic platelet dysfunction, and the use of anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents are probable risk factors.

Uremic optic neuropathy causes a rapidly progressive vision loss that responds to hemodialysis and corticosteroid treatment. Isolated peripheral mononeuropathies occur in uremic patients from compression or entrapment or from intramuscular hemorrhage. Hyperkalemia sometimes is responsible for a flaccid quadriparesis that responds to electrolyte correction. Treatment with aminoglycoside antibiotics in uremic patients can lead to cochlear, vestibular, or neuromuscular junction disturbances, and a myopathy sometimes results from electrolyte disturbances, corticosteroid treatment, or the end-stage kidney disease itself (Campistol, 2002).

Neurological Complications of Dialysis

In patients undergoing dialysis for longer than 1 year, a fatal encephalopathy called dialysis dementia may develop. Hesitancy of speech, leading to speech arrest, is a characteristic early feature. Intellectual function declines with time, and delusions, hallucinations, seizures, myoclonic jerking, asterixis, gait disturbances, and other neurological abnormalities ultimately develop. Death usually occurs within 6 to 12 months of onset of signs and symptoms. Increased cerebral concentrations of aluminum at postmortem examination suggested aluminum intoxication as the cause of dialysis dementia. Dialysis dementia has become much less common since removal of aluminum from dialysates (Rob et al., 2001). Deferoxamine, a chelating agent that binds aluminum, treats dialysis dementia, but the optimal duration of treatment is unclear. Deferoxamine may actually exacerbate or precipitate encephalopathy in patients with very high serum aluminum concentrations, and it also causes visual and auditory disturbances.

Electrolyte Disturbances

Potassium

The difference in the concentrations of intracellular and extracellular potassium creates the resting membrane potential of nerve and muscle cells. Disturbances of serum potassium adversely affect cardiac and neuromuscular function. The hereditary periodic paralyses are discussed in Chapter 79.

Pituitary Disease

Cushing Disease and Syndrome

The cause of Cushing disease is excessive secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone from the pituitary gland. The clinical features are truncal obesity, hypertension, acne, hirsutism, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, and menstrual irregularities. Mental changes are common and include anxiety, agitation, insomnia, depression, euphoria, mania, and psychoses. Proximal muscle weakness and wasting are common, especially in the legs. Muscle biopsy shows type II fiber atrophy, a characteristic feature of muscle in patients who receive long-term corticosteroid therapy (see Chapter 79); electromyographic findings generally are normal. The constellation of clinical features that constitutes Cushing syndrome is also a feature of the paraneoplastic syndrome of ectopic secretion of ACTH, and occurs in association with adrenal adenomas and after long-term corticosteroid treatment as well.

An enlarging pituitary adenoma may cause a visual field defect (Fig. 49A.10). Treatment of Cushing disease by bilateral adrenalectomy sometimes leads to rapid expansion of the underlying pituitary adenoma (Nelson syndrome), with compression of other cranial nerves, especially cranial nerve III. Intracranial hypertension is a recognized complication of Cushing syndrome and occurs particularly after resection of the pituitary adenoma.

Thyroid Disease

Hyperthyroidism

Several neuromuscular disorders are associated with hyperthyroidism. Most common is a proximal myopathy accompanied by fasciculations. Its mechanism is unknown, but the severity of myopathy does not correlate with the severity of thyroid abnormality. Serum creatine kinase levels generally are normal. Improvement occurs with treatment of the underlying thyroid disorder. Hyperthyroidism and myasthenia gravis often coexist. Both are immune-mediated disorders (see Chapter 78). Treatment of one disorder, however, does not have any predictable effect on the other.

Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis is similar to familial hypokalemic periodic paralysis (see Chapter 79). It is most common in persons of Asian heritage, and the hyperthyroidism may be clinically silent. Episodes of weakness occur after activity or after meals with high carbohydrate content. Potassium administration treats the acute attacks, and nonselective beta-blockers may both help alleviate the acute attack and prevent recurrence of paralytic attacks (Kung, 2006). Correction of the thyroid disorder cures the periodic paralysis.

Hashimoto Thyroiditis

Hashimoto thyroiditis is a chronic autoimmune-mediated thyroiditis, probably related to both genetic and environmental factors. An association exists with myasthenia gravis and less clearly with giant cell arteritis and vasculitic peripheral neuropathy. In addition, a relapsing encephalopathy may occur in association with Hashimoto thyroiditis and high titers of antithyroglobulin and antithyroperoxidase antibodies. Confusion, altered level of consciousness, and seizures are common presenting features. Tremulousness occurred in 80%, transient aphasia in 80%, and myoclonus in 65% of the patients in the series reported by Castillo and associates (2006). Gait ataxia (affecting 65% of the patients) and sleep abnormalities (reported by 55%) also are common. The EEG is diffusely abnormal, and CSF protein concentration is increased without an associated pleocytosis, but often accompanied by markers of inflammation including an elevated Ig index or unique CSF oligoclonal bands. MRI or isotope brain scan results may be abnormal but often are unremarkable. The diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis should be a consideration, even in the presence of a normal serum thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration and ESR. Treatment is with corticosteroids. The long-term prognosis is good, but relapses are expected and steroid-sparing immunosuppressive drugs are often necessary.

Adrenal Glands

Pheochromocytoma

Pheochromocytoma is associated with neurofibromatosis and von Hippel-Lindau disease (see Chapter 65). The initial features of pheochromocytoma are paroxysmal clinical features of excessive catecholamine secretion: headache, hyperhidrosis, palpitations, cardiac arrhythmias, tremulousness, and anxiety. Most patients have hypertension, and seizures occur in approximately 5%. Malignant pheochromocytomas are rare, and metastatic tumors may respond to radiation therapy.

Diabetes Mellitus

Peripheral Nervous System

In developed countries, diabetes is the most common cause of polyneuropathy (see Chapter 76). The mechanism of neuropathy is not established but may be either metabolic or vascular. Between 10% and 20% of newly diagnosed diabetic patients exhibit evidence of neuropathy. Prediabetes, as diagnosed by a glucose tolerance test demonstrating impaired glucose handling, can be associated with a painful sensory polyneuropathy. Exclude the diagnosis of diabetes in all patients presenting with an otherwise idiopathic sensory-predominant neuropathy (Singleton et al., 2005).

Diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy is characterized by pain and asymmetrical limb weakness, usually involving the thighs and often accompanied by weight loss. A diabetic plexopathy or polyradiculopathy, rather than a femoral neuropathy, probably accounts for most cases of diabetic amyotrophy (Dyck and Windebank, 2002). Symptoms are rapidly progressive but stabilize after a few weeks; gradual but often incomplete recovery occurs over the following months or years.

A specific treatment for diabetic neuropathy is not available, but complete control of the diabetes is imperative. In recipients of pancreatic islet transplants, diabetic neuropathy may stabilize or even regress (Lee et al., 2005). Painful neuropathies may respond to standard pharmacological measures to treat neuropathic pain (Chapter 44). Care of the feet is important, especially in patients with sensory neuropathy, to prevent ulceration.

Bernard S.A., Gray T.W., Buist M.D., et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557-563.

Boeken U., Litmathe J., Feindt P., et al. Neurological complications after cardiac surgery: risk factors and correlation to the surgical procedure. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;53:33-36.

Brouns R., De Deyn P.P. Neurological complications in renal failure: a review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;107:1-16.

Burns T.M., Schaublin G.A., Dyck P.J. Vasculitic neuropathies. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:89-113.

Cadranel J.F., Lebiez E., Di Martino V., et al. Focal neurological signs in hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: an underestimated entity? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:515-518.

Campistol J.M. Uremic myopathy. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1901-1913.

Castillo P., Woodruff B., Caselli R., et al. Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:197-202.

Cervera R., Piette J.C., Font J., et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019-1027.

Chaudhry V., Umapathi T., Ravich W.J. Neuromuscular diseases and disorders of the alimentary system. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:768-784.

Connolly S.J., Pogue J., Hart R.G., et al. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2066-2078.

Cuadrado M.J., Khamashta M.A., Ballesteros A., et al. Can neurologic manifestations of Hughes (antiphospholipid) syndrome be distinguished from multiple sclerosis? Analysis of 27 patients and review of the literature. Medicine. 2000;79:57-68.

de Bruijn S.F., Agema W.R., Lammers G.J., et al. Transesophageal echocardiography is superior to transthoracic echocardiography in management of patients of any age with transient ischemic attack or stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2531-2534.

Dougherty M.J., Calligaro K.D. How to avoid and manage nerve injuries associated with aortic surgery: ischemic neuropathy, traction injuries, and sexual derangements. Semin Vasc Surg. 2001;14:275-281.

Dyck P.J.B., Windebank A.J. Diabetic and nondiabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathies: new insights into pathophysiology and treatment. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:477-491.

Farwell D.J., Freemantle N., Sulke N. The clinical impact of implantable loop recorders in patients with syncope. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:351-356.

Gage B.F., Waterman A.D., Shannon W., et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864-2870.

Goransson L.G., Herigstad A., Tjensvoll A.B., et al. Peripheral neuropathy in primary Sjogren syndrome: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1612-1615.

Hadjivassiliou M., Grünewald R.A., Kandler R.H., et al. Neuropathy associated with gluten sensitivity. J. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1262-1266.

Heiro M., Nikoskelainen J., Engblom E., et al. Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis: a 17-year experience in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2781-2787.

Hinkle D.A., Raizen D.M., McGarvey M.L., et al. Cerebral air embolism complicating cardiac ablation procedures. Neurology. 2001;56:792-794.

Hnath J.C., Mehta M., Taggert J.B., et al. Strategies to improve spinal cord ischemia in endovascular thoracic aortic repair: outcomes of a prospective cerebrospinal fluid drainage protocol. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:836-840.

Kojouri K., Vesely S.K., George J.N. Quinine-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura–hemolytic uremic syndrome: frequency, clinical features, and long-term outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:1047-1051.

Kung A.W. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2490-2495.

Lee T.C., Barshes N.R., O’Mahony C.A., et al. The effect of pancreatic islet transplantation on progression of diabetic retinopathy and neuropathy. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2263-2265.

Levy Y., Uziel Y., Aandman G., et al. Response of vasculitic peripheral neuropathy to intravenous immunoglobulin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:779-786.

Manzel K., Tranel D., Cooper G. Cognitive and behavioral abnormalities in a case of central nervous system Whipple disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:399-403.

Marie R.M., Le Biez E., Busson P., et al. Nitrous oxide anesthesia-associated myelopathy. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:380-382.

McKeon A., Vaughan C., Delanty N. Seizure versus syncope. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:171-180.

McKhann G.M., Grega M.A., Borowicz L.M., et al. Stroke and encephalopathy after cardiac surgery: an update. Stroke. 2006;37:562-571.

Nussmeier N.A. A review of risk factors for adverse neurologic outcome after cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2002;34:4-10.

Papadopoulos M.C., Davies D.C., Moss R.F., et al. Pathophysiology of septic encephalopathy: a review. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3019-3024.

Prengler M., Pavlakis S.G., Prohovnik I., et al. Sickle cell disease: the neurological complications. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:543-552.

Rajkumar S.V., Gertz M.A. Advances in the treatment of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2413-2415.

Ringleb P.A., Strittmatter E.I., Loewer M., et al. Cerebrovascular manifestations of Takayasu arteritis in Europe. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1012-1015.

Rob P.M., Niederstadt C., Reusche E. Dementia in patients undergoing long-term dialysis: etiology, differential diagnoses, epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:691-699.

Rosenbaum R. Neuromuscular complications of connective tissue diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:154-169.

Rossetti A.O., Oddo M., Logroscino G., et al. Prognostication after cardiac arrest and hypothermia: a prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:301-307.

Santos E., Shaunak S., Renowden S., et al. Treatment of refractory neurosarcoidosis with Infliximab. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:241-246.

Selnes O.A., Grega M.A., Bailey M.M., et al. Cognition 6 years after surgical or medical therapy for coronary artery disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:581-590.

Singleton J.R., Smith A.G., Russell J., et al. Polyneuropathy with impaired glucose tolerance: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2005;7:33-42.

Siva A., Fresko I. Behçet’s disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2:435-448.

Soteriades E.S., Evans J.C., Larson M.G., et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:878-885.

Theodoridou A., Settas L. Demyelination in rheumatic diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:290-295.

Tseng M.T., Hsieh S.C., Shun C.T., et al. Skin denervation and cutaneous vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Brain. 2006;129:977-985.

Wityk R.J., Goldsborough M.A., Hillis A., et al. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging in patients with neurologic complications after cardiac surgery. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:571-576.

* Chapter 49A discusses neurological complications of systemic disease in adults. Chapter 49B discusses the same subject in children. Some disorders are discussed in both subchapters but with a different emphasis.