19 Neurological Complications of Bone Marrow and Organ Transplantation

Introduction

Organ transplantation is the only curative treatment for advanced cases of kidney, heart, liver, or lung failure. Bone marrow transplantation is performed in patients with otherwise untreatable leukemias, lymphomas, or storage disorders. Following transplantation, 30% to 60% of patients develop neurological complications.1 The differential diagnosis includes preexisting complications of the underlying disease, intraoperative complications, metabolic disorders, and side effects of the necessary immunosuppressive medication. Immunosuppressants may either directly cause neurotoxicity or indirectly promote an increased rate of central nervous system (CNS) infections and secondary CNS malignancies. Although the rate of metabolic encephalopathies or opportunistic CNS infections is quite similar for all posttransplantation patients, certain neurological syndromes are typical to transplantation of specific organs (see Table 19-1).

TABLE 19-1 Specific and Common Complications Following Organ Transplantation

| Transplantation | Complication |

|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Intracerebral hemorrhage due to thrombocytopenia Bacterial CNS infection (early period after transplantation) Viral CNS infection (especially herpes viruses) Leukoencephalopathy Neurologic manifestations of graft-versus host disease: myasthenia, myositis, polyneuropathy, central nervous system involvement |

| Liver | Brain edema/elevated intracranial pressure due to acute liver failure Intracerebral hemorrhage due to coagulation disorders Central pontine or extrapontine myelinolysis Brachial plexus lesion (pulmonary and cerebral aspergillosis) |

| Kidney | Femoral nerve lesion (lateral cutaneous femoral nerve) Hypertensive encephalopathy Encephalopathy due to acute organ rejection |

| Heart | Perioperative cerebral emboli Hypoxic-ischemic brain damage Phrenic nerve or brachial plexus lesion Aseptic meningitis following OKT3 (CNS lymphoma) |

| Lung | Air embolism (see heart transplantation) |

| Pancreas | Angiopathy Carpal tunnel syndrome |

Clinical Syndromes

Clinical evaluation is limited in the acute phase following organ transplantation by the necessity of treatment with analgesics and sedative drugs as well as by the severe illness of the patients. The unconscious patient in the intensive care unit (e.g., due to drugs or metabolic encephalopathy) may develop increased depth of coma, focal or generalized epileptic seizures, asymmetric reactions to pain stimuli, pupillary abnormalities, or specific oculomotor findings (e.g., vertical divergence), that indicate a CNS complication. After organ transplantation, conscious patients may experience nonspecific symptoms such as headaches, visual disturbances, delirium, psychosis, somnolence, or epileptic seizures. These symptoms may be caused by cerebrovascular complications, CNS infections, metabolic disturbances, or pharmacological neurotoxicity. An overview of the neurological differential diagnosis following organ transplantation, according to clinical syndromes, is given in Table 19-2.

TABLE 19-2 Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Syndromes Following Organ Transplantation

| Symptom | Etiology | Risk factor (transplantation) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute coma | Intracerebral hemorrhage Cerebral ischemia Status epilepticus |

Thrombocytopenia (BMT, LTX), coagulation disorder (LTX, BMT) Cardiac emboli (HTX), endocarditis (BMT), air embolism (HTX, LuTX) Metabolic disorder, neurotoxicity, CNS infection |

| Impaired consciousness | Metabolic Neurotoxicity CNS infection Myelinolysis |

Hepatic encephalopathy (LTX, organ failure), uremia (KTX), hypomagnesemia Cyclosporine/tacrolimus (LTX, HTX) Meningitis: Listeria, Cryptococcus; Encephalitis: CMV, HSV, VZV; Cerebritis/abscess: Aspergillus, Toxoplasma, Nocardia Hyponatremia (LTX) |

| Postoperative coma | Cerebral hypoxia Increased intracranial pressure Pharmacogenic Myelinolysis Ischemia/hemorrhage |

Intraoperative complication (HTX, LuTX), Brain edema (LTX) Sedatives/anesthetics See above See above |

| Focal neurological signs | Ischemia/hemorrhage CNS infection Neurotoxicity |

See above Abscess: Aspergillus, Nocardia, Toxoplasma, PML Cyclosporine/tacrolimus (cortical blindness) |

| Seizures | Neurotoxicity Metabolic Ischemia/hemorrhage CNS infection |

Cyclosporine/tacrolimus Uremia, liver failure, hypo/hypernatremia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, hypo/hyperglycemia See above See above |

| Neck stiffness | Meningitis (infectious agent) Aseptic meningitis |

Immunosuppression (BMT): Listeria, Cryptococcus OKT3 (HTX) |

| Headache | Pharmacogenic Meningitis |

Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, OKT3 See above |

| Tetraparesis | Pharmacogenic Neuropathy Myopathy |

Muscle relaxants, steroid myopathy Critical illness polyneuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome Critical illness myopathy, myositis (BMT) |

| Tremor (ataxia) | Neurotoxicity Encephalopathy CNS infection |

Cyclosporine/tacrolimus Organ failure (LTX, KTX) Viral encephalitis, Legionella |

BMT = bone marrow transplantation, LTX = liver transplantation, HTX = heart transplantation, KTX = kidney transplantation, LuTX = lung transplantation, CMV = cytomegalovirus, HSV = herpes simplex virus, VZV = varizella zoster virus, PML = progressive multifocal leukencephalopathy (JC virus encephalitis)

Investigations

The classification of clinical syndromes occurring after transplantation requires neuroradiological, laboratory, microbiological, and electrophysiological investigation. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify ischemic infarction, intracerebral bleeding, brain abscess, granuloma, white matter abnormalities, or brain edema.2 Laboratory parameters should include electrolytes, glucose, ammonia, renal function, coagulation status, and concentration of immunosuppressants (cyclosporine or tacrolimus). The examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should include testing for routine parameters, and microbiological or serological testing for bacteria and fungi, including specific antigen testing as well as cytological examination and culture. In cases of a suspected viral etiology, PCR and serological CSF/serum antibody index have to be determined. Systemic infections, mainly pulmonary infection with Aspergillus, Nocardia, and cryptococci, are potential sources of secondary CNS infections and must be diagnosed, or ruled out if suspected. Electroencephalography is necessary for patients with epileptic seizures or suspected nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

Neurotoxicity of Immunosuppressants

Cyclosporine

Neurological complications following cyclosporin A occur in 15% to 30% of patients.3 The most common complications are isolated tremor (40%), headache (10% to 20%), and distal sensory deficits (electrophysiological examination shows a combined demyelinating and axonal neuropathy only in severe cases). About 5% of patients develop severe neurological side effects, with predominantly two distinct clinical syndromes: (1) Acute neurotoxicity may occur within the first weeks after transplantation as an encephalopathy combined with headache, dysarthria, depressive or manic symptoms, visual hallucinations, cortical blindness, seizures, or impaired consciousness, and (2) weeks to months after transplantation, cyclosporine neurotoxicity can manifest as a subacute motor syndrome with hemiparesis, paraparesis, or tetraparesis, possibly accompanied by cerebellar tremor, ataxia, and cognitive impairment. Cyclosporine is epileptogenic, and 2% to 6% of patients develop focal or generalized seizures. Status epilepticus may occur in patients with high cyclosporine serum levels.

Magnetic resonance imaging using FLAIR sequences typically shows confluent parieto-occipital white matter lesions without contrast enhancement.4 CSF analysis shows elevated CSF albumin concentrations in almost all patients with cyclosporine neurotoxicity because of impaired blood-brain barrier function.

Tacrolimus

Neurotoxicity is observed in 30% to 50% of patients following organ transplantation. Symptoms include headache, sensory deficits, tremor, anxiety, nightmares, and sleep disorders. Severe neurologic complications include disorientation, dysarthria, epileptic seizures, encephalopathy, apraxia, akinetic mutism, and impaired consciousness and occur in about 5% of patients, mainly during the initial treatment.5 Tacrolimus has been reported to cause a severe demyelinating polyneuropathy, which responds to treatment with corticosteroids or immunoglobulins, as well as a changeover to cyclosporine.6 In such cases, however, polyradiculitis due to cytomegalovirus infection (CMV) has to be ruled out.

Steroids

Common neurological side effects of steroids include myopathies and psychiatric symptoms.7 It is probable that 50% of patients treated with medium to high doses of steroids for more than 3 weeks will develop a proximal myopathy (manifesting initially in the hip muscles). Because it is seldom possible to reduce the dosage in symptomatic patients, a nonfluorized steroid should be tried instead. Steroid myopathy usually resolves only after 2 to 8 months following discontinuation.8,9 Mood impairment occurs in almost all patients taking steroids, and some develop mild psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, sleeplessness, and reduced concentration. Steroid-induced psychosis has been reported in about 3% of patients, but affective disorders, schizophrenic syndromes or delirium have also been described. Symptomatic treatment with neuroleptic drugs, valproic acid (in patients with manic syndromes), or sedatives will also be necessary. Epidural lipomatosis with compression of the cord or cauda equina may occur rarely in patients who receive more than 30 mg prednisolone daily (or equivalent doses of another steroid). Epidural lipomatosis manifests with thoracic or lumbar pain, radicular syndromes, or myelopathy. Neurosurgical treatment (decompression and resection) may be necessary, but the discontinuation of steroids has also been reported to cause improvement.10

OKT3

Neurologic side effects occur in 2% to 14% of patients,with a latency of 24 to 72 hours after OKT3 treatment, and include aseptic meningitis with fever, headache, neck stiffness, and CSF pleocytosis. Meningitis rarely occurs after pretreatment with steroids, and resolves—when CSF microbiological cultures are negative—within days, even when OKT3 treatment is continued.11 Patients on OKT3 in rare instances develop an encephalopathic syndrome with fever, apathy, increased muscle rigidity, CSF pleocytosis, and brain edema. Single patients with potentially reversible, subcortical, contrast-enhancing MRI lesions have also been described.12

CNS INFECTIONS

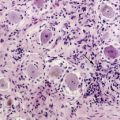

After organ transplantation, CNS infections occur in about 5% to 10% of patients, with a death rate of 44% to 77%.13 Otherwise-typical clinical signs like fever or neck stiffness may be absent in these patients, and the initial clinical examination may be obscured by the postoperative status (use of analgesics and sedatives) and organ failure. The presence of a systemic infection, possibly with secondary CNS involvement, is of diagnostic relevance. Most patients with cerebral Aspergillus or Nocardia asteroides infection have a primary pulmonary infection, and in many patients with Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis, primary infection of the skin or the lung can be shown. The clinical syndrome also helps in the differential diagnosis, since an acute meningitis is often caused by Listeria monocytogenes, whereas in patients with subacute or chronic meningitis, Cryptococcus or other fungi are generally found. Encephalitis can be caused by many viruses (e.g., herpes simplex, varicella-zoster, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus types 6–8, BK virus, and adenovirus) and, rarely, by bacteria. Slowly deteriorating cognitive impairment with additional focal neurological signs is typically caused by a JC papovavirus infection (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy). Focal space-occupying infectious lesions or abscesses are caused by Aspergillus, Toxoplasma gondii, Listeria, or Nocardia infections.14

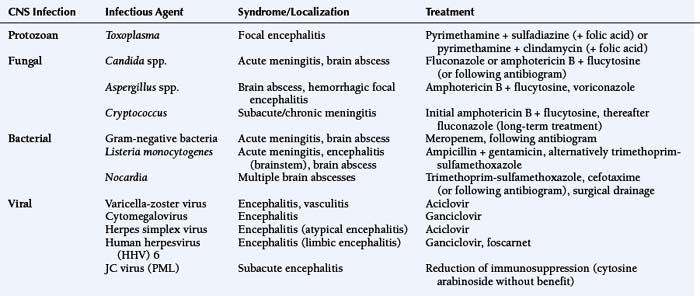

Treatment recommendations for CNS infections following organ transplantation are given in Table 19-3. The additive nephrotoxicity of immunosuppressive medication (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) and others such as acyclovir, aminoglycosides, fluconazole, or amphotericin B has to be considered, and the dosage of antibiotic/antiviral drugs has to be adjusted to actual renal clearance function.

SEIZURES

Epileptic seizures, which occur in 4% to 16% of organ recipients, are generally caused by neurotoxicity (cyclosporine, tacrolimus), metabolic disturbances, or hypoxic-ischemic CNS lesions. Hypoxia-induced seizures, in general, manifest within the first week after heart or liver transplantation. CNS infections or cerebral neoplasms are less likely to cause seizures. Since epileptic seizures often disappear following a reduction of immunosuppression, the normalization of metabolic disorders, or the treatment of CNS infections, a continuous antiepileptic medication is not necessary in all patients.15 Patients with repeated seizures or with status epilepticus should, however, be given benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam 1 to 2 mg IV, respiratory depression has to be considered with higher doses) and anticonvulsants.

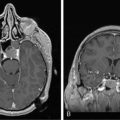

SECONDARY LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISEASE

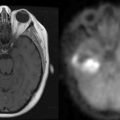

CNS involvement occurs in 15% to 25% of patients with lymphoproliferative disease following organ transplantation, but the majority of patients have primary isolated CNS lymphoma.16,17 The high frequency of CNS lymphoma might be due to the particular immunologic situation of the brain, where transformed viral B cells are more likely to survive. Clinical symptoms of lymphoproliferative CNS disease consist of cognitive disturbances and focal neurological signs. CT and MRI imaging show hyperintense lesions (T2-weighted images) with contrast enhancement most often in the periventricular areas, in the deep white matter, or in the basal ganglia, but multifocal or meningeal involvement may also occur. The presence of CNS lymphoma must be proven histologically by stereotactic biopsy.

Treatment of CNS lymphoma usually consists of systemic chemotherapy, but the reduction of immunosuppression and administration of acyclovir (or alpha-interferon) have been discussed.18 Although patients with CNS lymphoma after organ transplantation have not been included in clinical trials, treatment recommendations, by analogy to immunocompetent patients with primary CNS lymphoma, consist of initial systemic chemotherapy followed by irradiation when necessary (see chapter on primary CNS lymphoma).19 Systemic treatment with anti-B-cell antibody has no beneficial effect on CNS lymphoma, but single patients with complete remission have been described after intrathecal anti-B-cell antibody treatment. These data, however, must be confirmed in a larger, blinded study. In general, prognosis of CNS lymphoma after organ transplantation is poor, and the death rate exceeds that of systemic lymphoproliferative diseases (36% to 72%).

Neurological Complications Following Transplantation of a Specific Organ

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Depending on the underlying illness, autologous, syngeneic, or allogeneic transplantation is performed. Because autologous transplantation entails the reinfusion of the patient’s own bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells, the subsequent course of the patient is in general uncomplicated, and immunosuppression is not necessary. Neurological complications occur in the form of intracerebral bleeding during the thrombocytopenic period and as metabolic encephalopathy following organ failure.20 Syngeneic transplantation is performed between homozygotic twins, and is thus based on an immunological situation identical to that of autologous transplantation. Conversely, in allogeneic transplantation, bone marrow (or peripheral blood stem cells) from an HLA-identical family member or from an unrelated donor is transferred. These patients require prophylactic immunosuppression with cyclosporine, due to the mismatch of minor histocompatibility antigens. Despite treatment, 40% to 60% of them develop graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). After allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, patients are exposed to various types of primary and secondary CNS damage.21,22 Depending on the study design, neurological complications develop in 11% to 77%, and lead to death in 6% to 26%.23 Cerebral ischemia occurs in 3% to 9% of the patients, 2% to 7% of the patients develop intracranial hemorrhage, and 7% to 37% suffer from usually-reversible metabolic encephalopathy.24,25 Immunosuppression causes neurotoxicity in up to 15% (see section on neurotoxicity of immunosuppressants), and 5% to 15% of the patients acquire CNS infections after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Cerebral relapse of the original hematologic malignancy is observed in mixed study populations in 2% to 5% of the patients. With acute lymphatic leukemia, the risk of CNS relapse is about 7%, despite prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate treatment.26 Buffy coat treatment (infusion of mononuclear cells from the initial donor) can be performed in patients with leukemia recurrence in an attempt to utilize the graft-versus-leukemia effect, but this may lead to severe GvHD.

The etiology of cerebral ischemic infarctions includes nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, a hypercoagulability state, or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Intracranial bleeding (i.e., subdural hematoma or parenchymal bleeding) is most often due to thrombocytopenia. CNS infections are more frequent after bone marrow transplantation than after other organ transplants, because of the severe immunosuppression required and the initial leukopenia.27 During the early phase after transplantation, patients are at high risk for infections with gram-negative bacteria, viuses (especially herpes viruses) and fungi. Cellular and humoral immunity is still reduced during the first year after bone marrow transplantation despite hematologic reconstitution. Viral (e.g., CMV) and protozoan (e.g., Toxoplasma gondii) infections are particularly frequent in patients with chronic GvHD.

Severe leukencephalopathy of unknown etiology may occur years after bone marrow transplantation. It can manifest as cognitive impairment, tetraparesis, or as a cerebellar syndrome. Chronic GvHD and the resulting immunosuppression have been identified as risk factors for clinical, neuropsychological, and MRI abnormalities in long-term survivors. Neurological complications of chronic GvHD, which may cause scleroderma-like skin changes and liver or gut involvement, include polymyositis, myasthenia gravis, and polyneuropathy syndromes (also described in patients with acute GvHD). In these patients, treatment does not differ from that for other GvHD manifestation (immunosuppression, i.e., with steroids). Patients with myasthenia require additional medication with cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine). Possible CNS involvement during chronic GvHD, which has been described in case reports and animal experiments, should be suspected in patients with vasculitis-like or encephalitis-like disease.28 Stereotactic brain biopsy is recommended, if endocarditis and CNS infections have been ruled out. If the neuropathological findings are positive, trial treatment with steroids (500 to 1000 mg IV daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2 every 4 weeks for 2 to 4 months) is justified, despite the considerable risks (marrow toxicity, immunosuppression).

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Liver transplantation is performed in patients with advanced organ failure, some causes of which include viral hepatitis, alcoholic cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, Wilson disease, and congenital liver disorders. At the time of transplantation, most patients have metabolic encephalopathy and polyneuropathy. Approximately 50% of the patients with hepatic encephalopathy grade III or IV develop diffuse brain edema with a possible increase in intracranial pressure. This may be temporarily reversed by aggressive treatment with osmotic therapy and barbiturate anesthesia, thus in some cases making emergency transplantation possible. Perioperative intracranial pressure monitoring with implanted devices cannot be recommended because of the frequency of bleeding complications.29 During liver transplantation surgery, extensive intraoperative blood loss may cause episodes of hypotension, during which the necessary replacement with blood products and crystalloid infusions may lead to electrolyte imbalance.

Neurological complications following liver transplantation occur in 20% to 30% of patients.30 Encephalopathy due to metabolic disorders and neurotoxicity of immunosuppressants are most frequent. Other complications include epileptic seizures, plexus or peripheral nerve lesions, ischemic brain infarctions, and CNS infections. Because of hepatic encephalopathy in the early transplantation phase, neurological complications may be difficult to recognize. Autopsy studies have reported neuropathological abnormalities in 70% to 90% of patients.31 Of these, the most frequent are anoxic-ischemic brain damage, cerebral infarctions, intracerebral bleeding, and opportunistic CNS infections. Pontine or extrapontine myelinolysis, which is caused by intraoperative electrolyte and osmolarity changes due to mass transfusions, manifests clinically in approximately 2% of the patients, but is found in 10% of neuropathologically examined patients. Patients with liver transplantation develop neurotoxicity due to immunosuppressants more frequently than patients with other organ transplantations. This can be attributed to the extensive immunosuppression required, as well as the frequent presence of risk factors, e.g., hypocholesterolemia and hypertension. In general, the neurological outcome after transplantation is worse in patients with alcohol-toxic liver cirrhosis or with acute liver failure (who more frequently have severe hepatic encephalopathy) than in patients with chronic liver failure of other etiology.

KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION

Kidney transplantation is performed in patients requiring hemodialysis due to kidney failure, some causes of which include glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy, and hypertensive kidney disease. The transplantation procedure itself does not pose any neurological risks, with the exception of occasionally occurring lesions of the femoral or lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (both with a favorable prognosis).32 Individual patients, however, have been reported to have spinal ischemia due to a vascular variant.33 Due to the frequently preexisting angiopathy, approximately 6% of patients develop cerebral ischemia and 1% intracerebral bleeding after kidney transplantation. As a result of the necessary immunosuppression, CNS infections and secondary lymphoproliferative diseases can occur. Specifically, patients who undergo a kidney transplantation can develop an encephalopathic syndrome with headache and epileptic seizures during acute organ rejection.34 This may be caused by a cytokine-mediated reaction just like the OKT3 side effects, but hypertensive encephalopathy must be excluded. In general, a preexisting or relapsing uremia is a risk factor for transplantation-associated CNS disease, but metabolic encephalopathy may also occur in isolated instances.

HEART TRANSPLANTATION

Neurological complications are observed in up to 60% of the patients who undergo heart transplantation.35 Cerebral ischemic infarctions (which may often cause epileptic seizures) or intracerebral hemorrhage were found in clinical studies in 5% to 7% of the patients. Autopsy studies found cerebral ischemia or hypoxia in approximately 50% of the patients following heart transplantation. Rarely, intraoperative lesions of the brachial plexus or the phrenic nerve occur. Due to the extensive immunosuppression required, the rate of CNS infections (especially Toxoplasma) and the risk of a secondary lymphoproliferative disease are somewhat higher than after other organ transplantations.

LUNG TRANSPLANTATION

Neurological complications following lung transplantation have rarely been studied in detail. Aside from the possible sequelae due to extracorporeal circulation and immunosuppression (see sections on neurotoxicity of immunosuppressants and heart transplantation), cerebral air emboli have been described as a specific complication following lung transplantation in patients with bronchial fistulas.36 In general, the risk of hematogeneous CNS infection is elevated, due to the high rate of bacterial, viral (especially CMV), and fungal infections of the transplanted lung.

PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION

Pancreas transplantation is usually performed in combination with kidney transplantation in patients with severe complications due to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type I. These patients almost always have nephropathy, retinopathy, and polyneuropathy. Thus, following transplantation, cerebral ischemia may occur because of a preexisting diabetic angiopathy, or renal insufficiency may cause metabolic encephalopathy. The pancreatic transplantation itself usually does not cause any neurological complications. Although one study reported an increased occurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome following transplantation, polyneuropathy syndromes as well as autonomic neuropathy generally improve after combined pancreas and kidney transplantation.37

1. J.C. Adair, S.L. Woodley, J.B. O’Connell, et al. Aseptic meningitis following cardiac transplantation: clinical characteristics and relationship to immunosuppressive regimen. Neurology. 1991;41:249-252.

2. H.P. AdamsJr., G. Dawson, T.J. Coffman, et al. Stroke in renal transplant recipients. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:113-115.

3. G. Antonini, V. Ceschin, S. Morino, et al. Early neurologic complications following allogeneic bone marrow transplant for leukemia: A prospective study. Neurology. 1998;50:1441-1445.

4. M. Benkerrou, A. Durandy, A. Fischer. Therapy for transplant-related lymphoproliferative diseases. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1993;7:467-475.

5. R. Blanco, U. De Girolami, R.L. Jenkins, et al. Neuropathology of liver transplantation. Clin Neuropathol. 1995;14:109-117.

6. L.F. Bleggi-Torres, B.C. de Medeiros, B. Werner, et al. Neuropathological findings after bone marrow transplantation: an autopsy study of 180 cases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:301-307.

7. S.L. Bowyer, M.P. LaMothe, J.R. Hollister. Steroid myopathy: incidence and detection in a population with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985;76:234-242.

8. J.V. Campellone, D. Lacomis. Neuromuscular disorders. In: E.F.M. Wijdicks(Hrsg), editor. Neurologic complications in organ transplant recipients. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 1999:169-192.

9. D.J. Conti, R.H. Rubin. Infection of the central nervous system in organ transplant recipients. Neurol Clin. 1988;6:241-260.

10. W.M. Coplin, M.S. Cochran, S.R. Levine, et al. Stroke after bone marrow transplantation: frequency, aetiology and outcome. Brain. 2001;124:1043-1051.

11. C. de Brabander, J. Cornelissen, P.A. Smitt, et al. Increased incidence of neurological complications in patients receiving an allogenic bone marrow transplantation from alternative donors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:36-40.

12. M. Faraci, E. Lanino, G. Dini, et al. Severe neurologic complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Neurology. 2002;59:1895-1904.

13. J.A. Fishman, R.H. Rubin. Infection in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1741-1751.

14. D. Gallardo, C. Ferra, J.J. Berlanga, et al. Neurologic complications after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18:1135-1139.

15. R.L. Gilmore. Seizures and antiepileptic drug use in transplant patients. Neurol Clin. 1988;6:279-296.

16. L.S. Goldstein, M.T. Haug, J. Perl, et al. Central nervous system complications after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:185-191.

17. F. Graus, A. Saiz, J. Sierra, et al. Neurologic complications of autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in patients with leukemia: a comparative study. Neurology. 1996;46:1004-1009.

18. M.L. Gross, P. Sweny, R.M. Pearson, et al. Rejection encephalopathy. An acute neurological syndrome complicating renal transplantation. J Neurol Sci. 1982;56:23-34.

19. M. Guarino, A. Stracciari, P. Pazzaglia, et al. Neurological complications of liver transplantation. J Neurol. 1996;243:137-142.

20. M.S. Jog, J.E. Turley, H. Berry. Femoral neuropathy in renal transplantation. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21:38-42.

21. S.D. Lidofsky, N.M. Bass, M.C. Prager, et al. Intracranial pressure monitoring and liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. Hepatology. 1992;16:1-7.

22. G. Niedobitek, D.J. Mutimer, A. Williams, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection and malignant lymphomas in liver transplant recipients. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:514-520.

23. T. Nymann, D.K. Hathaway, T.E. Bertorini, et al. Studies of the impact of pancreas-kidney and kidney transplantation on peripheral nerve conduction in diabetic patients. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:323-324.

24. M.T. Pace, T.L. Slovis, J.K. Kelly, et al. Cyclosporin A toxicity: MRI appearance of the brain. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:180-183.

25. C.S. Padovan, T.A. Yousry, M. Schleuning, et al. Neurological and neuroradiological findings in long-term survivors of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:627-633.

26. P.M. Parizel, H.W. Snoeck, L. van den Hauwe, et al. Cerebral complications of murine monoclonal CD3 antibody (OKT3): CT and MR findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1935-1938.

27. R.A. Patchell. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in the transplant patient. Neurol Clin. 1988;6:297-303.

28. R.A. Patchell. Neurological complications of organ transplantation. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:688-703.

29. S. Pomeranz, E. Naparstek, E. Ashkenazi, et al. Intracranial haematomas following bone marrow transplantation. J Neurol. 1994;241:252-256.

30. L.J. Swinnen. Durable remission after aggressive chemotherapy for post-cardiac transplant lymphoproliferation. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;28:89-101.

31. D. van de Beek, W. Kremers, R.C. Daly, et al. Effect of neurologic complications on outcome after heart transplant. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:226-231.

32. E.F. Wijdicks, R.H. Wiesner, L.J. Dahlke, et al. FK506-induced neurotoxicity in liver transplantation. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:498-501.

33. E.F. Wijdicks, R.H. Wiesner, R.A. Krom. Neurotoxicity in liver transplant recipients with cyclosporine immunosuppression. Neurology. 1995;45:1962-1964.

34. J.R. Wilson, R.A. Conwit, B.H. Eidelman, et al. Sensorimotor neuropathy resembling CIDP in patients receiving FK506. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:528-532.

35. O.M. Wolkowitz, V.I. Reus, J. Canick, et al. Glucocorticoid medication, memory and steroid psychosis in medical illness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;823:81-96.

36. J. Zentner, K. Buchbender, M. Vahlensieck. Spinal epidural lipomatosis as a complication of prolonged corticosteroid therapy. J Neurosurg Sci. 1995;39:81-85.

37. S. Zivković. Neuroimaging and neurologic complications after organ transplantation. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17:110-123.